Published online Feb 24, 2017. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v7.i1.98

Peer-review started: November 29, 2016

First decision: December 15, 2016

Revised: December 21, 2016

Accepted: January 11, 2017

Article in press: January 13, 2017

Published online: February 24, 2017

Processing time: 87 Days and 6.1 Hours

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is an important medication used for maintenance immunosuppression in solid organ transplants. A common gastrointestinal (GI) side effect of MMF is enterocolitis, which has been associated with multiple histological features. There is little data in the literature describing the histological effects of MMF in small intestinal transplant (SIT) recipients. We present a case of MMF toxicity in a SIT recipient, with histological changes in the donor ileum mimicking persistent acute cellular rejection (ACR). Concurrent biopsies of the patient’s native colon showed similar changes to those from the donor small bowel, suggesting a non-graft specific process, raising suspicion for MMF toxicity. The MMF was discontinued and complete resolution of these changes occurred over three weeks. MMF toxicity should therefore be considered as a differential diagnosis for ACR and graft-versus-host disease in SITs.

Core tip: Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is a commonly used medication for maintenance immunosuppression in small intestine transplant (SIT) recipients. Enterocolitis is a known side effect of MMF therapy, but there is little literature describing its histological manifestations in SIT recipients. Our case shows that MMF enterocolitis can mimic acute cellular rejection (ACR) and highlights the importance of attempting to biopsy the native gastrointestinal tract in SIT recipients if possible. If the native biopsy is abnormal, drug toxicity should be considered as a differential diagnosis as it may show overlapping features with ACR.

- Citation: Apostolov R, Asadi K, Lokan J, Kam N, Testro A. Mycophenolate mofetil toxicity mimicking acute cellular rejection in a small intestinal transplant. World J Transplant 2017; 7(1): 98-102

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v7/i1/98.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v7.i1.98

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) acts by inhibiting inosine-5’-monophosphate dehydrogenase, leading to decreased purine synthesis in T and B lymphocytes. This inhibits lymphocyte proliferation and as a result suppresses cell mediated immunity and antibody formation, which are important factors in acute graft rejection[1].

Small intestine transplants (SITs) have a high risk of developing acute graft rejection, with nearly 50% of recipients developing at least one episode of rejection within one year of transplantation[2]. Prevention and early treatment of acute rejection is important in SITs due to its significant consequences. In a large single centre review of 500 small intestine and multi-visceral transplants persistent rejection was the leading cause of graft failure[3]. Current immunosuppression regimens to prevent rejection include induction therapy with antilymphocyte or anti-IL2 antibodies, followed by maintenance therapy with corticosteroids and tacrolimus[3,4]. MMF added to tacrolimus and corticosteroids may further reduce the risk of rejection in SIT recipients[5]. Our centre utilises MMF in addition to tacrolimus and corticosteroids for maintenance therapy in SITs.

A common side effect of MMF is enterocolitis, which clinically presents with non-specific symptoms of increased stomal output and abdominal distension. These same symptoms may also occur in SIT rejection. Biopsies must be obtained for histology to differentiate these potential complications in SIT recipients. Histological patterns of injury related to MMF toxicity have been described in the literature in both the upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) tracts[6-13]. Most of the existing literature describes histological features of MMF injury in native small and large intestine samples rather than in SITs, making it difficult to diagnose MMF injury in a SIT recipient. We describe a case of a SIT recipient who histologically appeared to have persistent acute cellular rejection (ACR). The patient had similar histological findings in his native colon, implicating MMF toxicity as the cause for the persistent changes.

A 47-year-old man underwent a combined SIT and renal transplant. He had short-gut syndrome with 35 cm of small bowel remaining after multiple resections for spontaneous volvulus. The native colon remained intact and functioning. He had end-stage renal failure due to oxalosis which had been demonstrated on pre-transplant renal biopsy. He received induction immunosuppression with pre-operative basiliximab 20 mg, with a second dose given on post-operative day 4. Early maintenance immunosuppression consisted of intravenous methylprednisolone, MMF 1000 mg BID, and tacrolimus titrated to a trough level of 10-12 ng/mL.

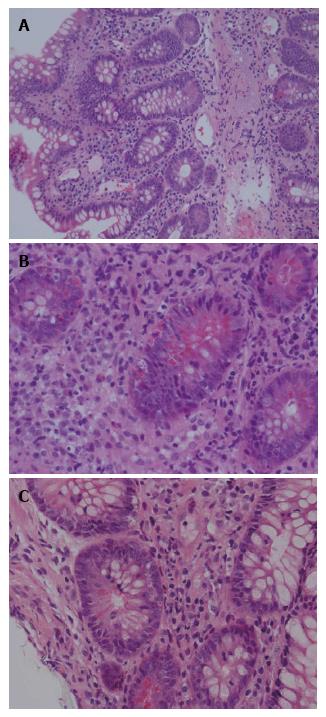

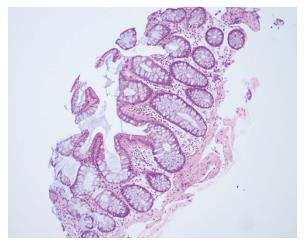

Protocol endoscopy and biopsy of the SIT and native colon, accessed via a chimney ileostomy, were performed on day 13 post-transplant. As per our institutional protocol, the biopsies were interpreted independently by two experienced transplant pathologists. The donor ileum and native colon appeared macroscopically normal. Donor ileal biopsy showed a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with activated lymphocytes, eosinophils and plasma cells and evidence of crypt epithelial injury associated with > 6 apoptotic bodies per 10 consecutive crypts (Figure 1). Native colonic biopsies were unremarkable at this time (Figure 2). A diagnosis of mild ACR was made. This was treated with pulsed methylprednisolone, as per our hospital’s protocol. A subsequent biopsy performed 3 d later demonstrated resolution of the ACR, again with normal colonic biopsies.

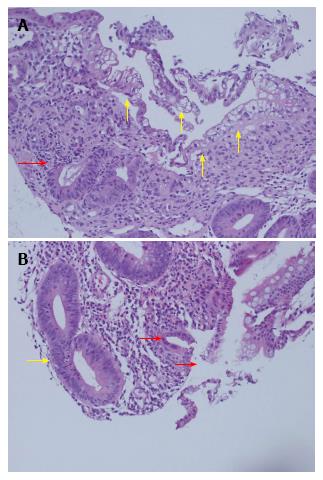

Further protocol endoscopy and biopsy of the SIT and native colon was performed on day 23. The donor ileum had macroscopically flattened villi and the native colon appeared normal. Biopsy of the donor ileum, from both the chimney and the graft proximal to the colonic anastomosis, demonstrated focal villous blunting and flattening, with multifocal erosion, superficial ulceration with neutrophil clusters and inflamed granulation tissue. In areas there was marked degeneration and vacuolation of the surface epithelium with sloughing, but no viral inclusions were identified on immunohistochemistry. There was mixed mononuclear inflammation with foci of crypt degeneration, neutrophilic cryptitis, areas of crypt drop-out and up to 10 apoptotic bodies per 10 crypts, without confluent apoptosis (Figure 3). In isolation these findings were concerning for at least moderately severe ACR, particularly in the setting of ACR only 10 d prior. An opinion was also sought from an international expert, who reviewed the biopsies, and felt that the changes in the small bowel were suspicious for moderate-severe ACR.

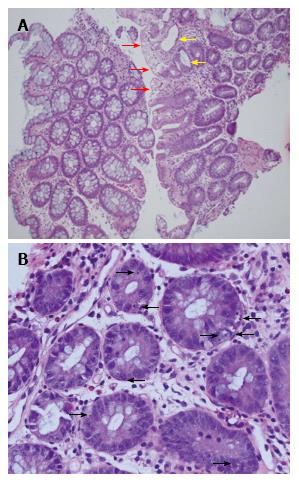

Importantly however, the native colonic biopsies also demonstrated surface epithelial vacuolation associated with crypt injury with dilatation, goblet cell depletion, focal attenuation of the epithelium and focally increased basal apoptosis (Figure 4). These new findings in the previously normal native colon suggested a non-graft specific pathological process and hence, in the absence of viral infection, or clinical features of graft-vs-host disease (GVHD), raised suspicion for MMF GI toxicity. We therefore chose to discontinue the MMF (substituted with azathioprine) and not give any specific treatment for rejection, pending an early repeat biopsy.

Further endoscopy and biopsy 4 d later (post-operative day 27) revealed significant improvement in histologic appearance with only low grade apoptosis, and by post-operative day 34 the endoscopic appearance was normal and histologic examination demonstrated normal villous architecture, regenerative crypts and 3-4 apoptotic bodies per 10 crypts. Native colonic biopsy showed evidence of healing injury and reduced apoptosis. Repeat biopsy on day 41 showed similar findings in the SIT and entirely resolved changes in the native colon. Viral inclusions were absent in all biopsy specimens.

The patient is now one year post transplant and has remained on azathioprine, tacrolimus and prednisolone. He currently has intestinal autonomy and a well-functioning renal graft and has had no further episodes of acute rejection.

Distinguishing ACR in a SIT from MMF toxicity presents a challenge for clinicians. This is due to the overlap of endoscopic and histopathologic findings in both conditions and the limited published literature describing histological changes related to MMF use in SITs.

ACR in a SIT can be suspected on endoscopic visualisation and diagnosed histologically. Endoscopic visualisation for detecting ACR was shown to have a sensitivity of 50% and specificity of 91% in SIT recipients undergoing surveillance endoscopy[14]. Abnormalities seen included erythema, friability, bleeding and ulceration of the mucosa as well as shortening, blunting and congestion of villi. MMF enterocolitis can present with similar findings on endoscopic visualisation, including erythema in one third of cases and erosions and ulcers less commonly[7,9]. No endoscopic abnormality is seen in approximately half of the histologically confirmed cases of GI injury attributable to MMF. Our patient had normal endoscopic appearances at the time that ACR was diagnosed. The subsequent endoscopy one week later showed flat villi, a finding that may have suggested ongoing ACR.

Histological features of ACR in SIT recipients include lymphocytic infiltration of the lamina propria, increased number of apoptotic bodies (typically > 6 apoptotic bodies per 10 consecutive crypts), crypt injury and dropout, and ulceration[4].

Recognition and early treatment of ACR in SIT recipients is important, as severe ACR of intestinal grafts has a 50% mortality rate[15]. The treatment of ACR involves high dose steroids or anti-lymphocyte therapy, with an aim to decrease the T-cell mediated immune response towards the graft[2]. In contrast, the treatment of MMF toxicity involves cessation or switching to an alternative agent. Our patient has an intestine-kidney transplant, and had also experienced mild ACR of his intestinal graft. Both of these reasons indicate the need for another immunosuppressant in place of MMF. We used azathioprine in this case, but rapamycin is an alternative agent that may be used[3].

Most of the studies describing histological features of GI mucosal injury from MMF excluded SIT recipients. To our knowledge, only one study of 15 biopsy specimens from four paediatric patients describes the histological changes of MMF injury in SIT recipients[16]. Lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate, villous blunting, vascular congestion and apoptotic bodies were the major histological changes described. Only one of 15 specimens in the study had > 6 apoptotic bodies per 10 crypts, and this biopsy was reported as mild ACR. Some of these features were seen on our patient’s day 23 biopsy, at which time the differential diagnoses of ACR and MMF mucosal injury were considered. Our patient’s day 23 biopsy showed higher crypt apoptotic counts than have been previously attributed to MMF in SITs. Further, and perhaps most importantly, the value of biopsying the remaining native bowel was highlighted by the fact that there was similar pathology evident, suggesting that the pathological process was non-graft specific and hence broadened the differential diagnosis to drug toxicity, GVHD and viral infection.

The histological features of MMF colitis have been described in a number of studies. These changes include acute colitis-like findings, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) like findings, crypt architectural disarray, erosive colitis and GVHD like features[7-13]. GVHD like features have also been described in ileal biopsies of patients on MMF and include crypt architectural disarray, villous blunting, oedema and crypt epithelial apoptosis[7]. Our patient’s day 23 ileal and colonic biopsies showed features of crypt apoptosis with associated active crypt epithelium injury, mucosal erosion and architectural disarray.

MMF-induced enterocolitis presented with similar clinical and histological findings to ACR in our case. Rapid resolution of clinical and histological abnormalities occurred after switching MMF to azathioprine. MMF enterocolitis should be considered as a differential diagnosis for SIT recipients with persistent ACR who are taking MMF. If at all possible, attempts should be made to concurrently biopsy the remnant native GI tract at the time of routine graft surveillance biopsies in order to determine whether observed histologic changes are graft specific.

A 47-year-old male small intestinal transplant (SIT) recipient recovering post-operatively with no specific symptoms.

The patient’s clinical examination was unremarkable during the case.

The major differential diagnoses for mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) toxicity are acute cellular rejection (ACR) and graft-versus-host disease.

Endoscopy revealed flattened villi in the donor ileum and a macroscopically normal native colon in patient.

Serial biopsies of the patient’s SIT and native colon initially showed features of ACR in the SIT and no abnormalities in the native colon, but subsequently showed pathological features in both the SIT and native colon which suggested a non-graft specific pathology.

MMF was switched to azathioprine, leading to resolution of the histopathological changes.

The case report is a unique case and there is very little data describing the histological effects of MMF in SIT recipients.

MMF enterocolitis is a common side effect of MMF therapy and histological changes associated with MMF use have been described in all sections of the gastrointestinal tract.

By performing concurrent biopsies of the SIT and native colon of patient, the authors identified MMF toxicity, a non-graft specific pathology, as the cause for patient’s persistent abnormal histological changes in the SIT.

It is an interesting work that describes a relevant drug toxicity.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Transplantation

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Akamatsu N, Kayaalp C, Ramos E, Salvadori M S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Allison AC, Eugui EM. Mechanisms of action of mycophenolate mofetil in preventing acute and chronic allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2005;80:S181-S190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sudan D. The current state of intestine transplantation: indications, techniques, outcomes and challenges. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:1976-1984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abu-Elmagd KM, Costa G, Bond GJ, Soltys K, Sindhi R, Wu T, Koritsky DA, Schuster B, Martin L, Cruz RJ. Five hundred intestinal and multivisceral transplantations at a single center: major advances with new challenges. Ann Surg. 2009;250:567-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vianna RM, Mangus RS, Tector AJ. Current status of small bowel and multivisceral transplantation. Adv Surg. 2008;42:129-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tzakis AG, Weppler D, Khan MF, Koutouby R, Romero R, Viciana AL, Raskin J, Nery JR, Thompson J. Mycophenolate mofetil as primary and rescue therapy in intestinal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:2677-2679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nguyen T, Park JY, Scudiere JR, Montgomery E. Mycophenolic acid (cellcept and myofortic) induced injury of the upper GI tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1355-1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Parfitt JR, Jayakumar S, Driman DK. Mycophenolate mofetil-related gastrointestinal mucosal injury: variable injury patterns, including graft-versus-host disease-like changes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1367-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Al-Absi AI, Cooke CR, Wall BM, Sylvestre P, Ismail MK, Mya M. Patterns of injury in mycophenolate mofetil-related colitis. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:3591-3593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Calmet FH, Yarur AJ, Pukazhendhi G, Ahmad J, Bhamidimarri KR. Endoscopic and histological features of mycophenolate mofetil colitis in patients after solid organ transplantation. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28:366-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Behling KC, Foster DM, Edmonston TB, Witkiewicz AK. Graft-versus-Host Disease-Like Pattern in Mycophenolate Mofetil Related Colon Mucosal Injury: Role of FISH in Establishing the Diagnosis. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2009;3:418-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Papadimitriou JC, Cangro CB, Lustberg A, Khaled A, Nogueira J, Wiland A, Ramos E, Klassen DK, Drachenberg CB. Histologic features of mycophenolate mofetil-related colitis: a graft-versus-host disease-like pattern. Int J Surg Pathol. 2003;11:295-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liapis G, Boletis J, Skalioti C, Bamias G, Tsimaratou K, Patsouris E, Delladetsima I. Histological spectrum of mycophenolate mofetil-related colitis: association with apoptosis. Histopathology. 2013;63:649-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Selbst MK, Ahrens WA, Robert ME, Friedman A, Proctor DD, Jain D. Spectrum of histologic changes in colonic biopsies in patients treated with mycophenolate mofetil. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:737-743. [PubMed] |

| 14. | O’Keefe SJ, El Hajj II, Wu T, Martin D, Mohammed K, Abu-Elmagd K. Endoscopic evaluation of small intestine transplant grafts. Transplantation. 2012;94:757-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lauro A, Bagni A, Zanfi C, Pellegrini S, Dazzi A, Del Gaudio M, Ravaioli M, Di Simone M, Ramacciato G, Pironi L. Mortality after steroid-resistant acute cellular rejection and chronic rejection episodes in adult intestinal transplants: report from a single center in induction/preconditioning era. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:2032-2033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Delacruz V, Weppler D, Island E, Gonzalez M, Tryphonopoulos P, Moon J, Smith L, Tzakis A, Ruiz P. Mycophenolate mofetil-related gastrointestinal mucosal injury in multivisceral transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:82-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |