Published online Jun 24, 2016. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v6.i2.447

Peer-review started: January 15, 2016

First decision: March 1, 2016

Revised: March 29, 2016

Accepted: May 10, 2016

Article in press: May 11, 2016

Published online: June 24, 2016

Processing time: 161 Days and 21.6 Hours

The differential diagnoses of a cavitary lung lesion in renal transplant recipients would include infection, malignancy and less commonly inflammatory diseases. Bacterial infection, Tuberculosis, Nocardiosis, fungal infections like Aspergillosis and Cryptococcosis need to be considered in these patients. Pulmonary cryptococcosis usually presents 16-21 mo after transplantation, more frequently in patients who have a high level of cumulative immunosuppression. Here we discuss an interesting patient who never received any induction/anti-rejection therapy but developed both BK virus nephropathy as well as severe pulmonary Cryptococcal infection after remaining stable for 6 years after transplantation. This case highlights the risk of serious opportunistic infections even in apparently low immunologic risk transplant recipients many years after transplantation.

Core tip: Here we discuss an interesting patient who never received any induction/anti-rejection therapy but developed both BK virus nephropathy as well as severe pulmonary Cryptococcal infection after remaining stable for 6 years after transplantation. This case highlights the risk of serious opportunistic infections even in apparently low immunologic risk transplant recipients many years after transplantation.

- Citation: Subbiah AK, Arava S, Bagchi S, Madan K, Das CJ, Agarwal SK. Cavitary lung lesion 6 years after renal transplantation. World J Transplant 2016; 6(2): 447-450

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v6/i2/447.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v6.i2.447

Fungal infections causing cavitary lung lesions usually manifest in transplant recipients who have received a high level of cumulative immunosuppression. We describe an unusual case, where a low risk transplant recipient who had been stable for 6 years developed severe pulmonary Cryptococcal disease and BK virus nephropathy.

A 40-year-old Indian man was admitted with low grade fever and dry cough for one month. He had end stage renal disease due to unclassified primary disease and had a live related renal transplantation with his sister as the donor in 2009. He was detected hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive before transplantation and has been on Tenofovir since then. He received no induction and was initially maintained on Tacrolimus, Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF) and Steroids. After a year, MMF was changed to Azathioprine due to financial constraints. He received Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole for 6 mo after transplantation but no primary prophylaxis for Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Tuberculosis (TB) or fungal infection. His postoperative course was uneventful and he maintained serum creatinine of 1.1-1.2 mg/dL. He is a non smoker.

Clinically, the patient was febrile, hemodynamically stable and hypoxemic (SPO2 92% on room air) requiring oxygen by mask. Investigations revealed pancytopenia (Hb 7.4 g/dL, total leucocyte count -3400/cu mm, platelet count -87000/cu mm) and high serum creatinine (2.5 mg%). Azathioprine was stopped. Tacrolimus trough level was 3.7 ng/mL. Urinalysis was unremarkable. Graft biopsy showed BK virus (BKV) nephropathy and serum BKV plasma load was more than 104 copies/mL.

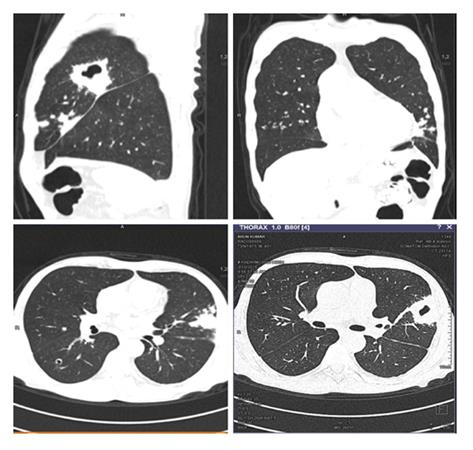

He was started empirically on broad spectrum antibiotics. Blood and urine cultures and quantitative CMV PCR assay were non-contributory. A non-contrast CT thorax showed bilateral, multiple, diffuse centrilobular and peribronchovascular cavitating nodules coalescing to form areas of consolidation with a larger cavity in apico posterior segment of upper lobe of left lung (Figure 1). Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid cultures was unrevealing. Serum Cryptococcal antigen was negative. Serum and BAL fluid galactomannan were negative.

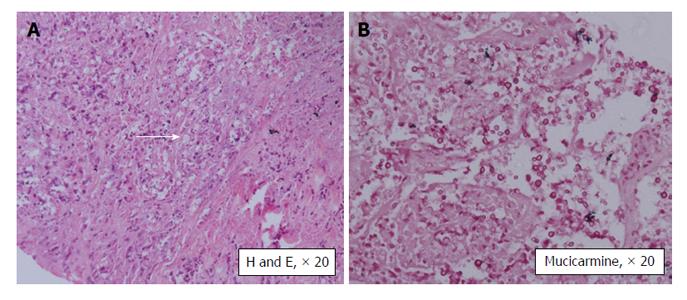

Since patient continued to be febrile, computed tomography guided biopsy of the cavitary lesion in the left lung was done and the histopathology (Figure 2) showed Cryptococcal infection. He was treated with liposomal Amphotericin for 6 wk and given Fluconazole prophylaxis. Flucytosine was not available at that time. Patient showed clinical as well as radiologic improvement and was discharged on oral fluconazole. His pulmonary infection has subsequently recurred and now he is being treated with a combination of Amphotericin and Flucytosine.

A renal transplant recipient may present with a cavitary lung lesion due to infection, malignancy (post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder) or inflammatory disease, though infections are the predominant causative factor[1-3]. TB is the commonest cause of cavitary lung lesions in endemic areas like India and patients may receive empiric anti-TB therapy if the index of suspicion for rarer infections is not high and investigations are non-contributory. Aspergillosis (either angioinvasive or chronic necrotizing form) is the most common fungal infection associated with cavitation. Other causes are Nocardiosis, Cryptococcosis, Actinomycosis and rarely Legionella pneumophila. In a sick patient, the possibility of septic emboli has to be kept in mind[1,2].

Cryptococcosis is the third most common fungal infection seen in transplant recipients[4,5]. It typically occurs late with median time to onset being 16 to 21 mo after renal transplantation. However our patient presented very late - 6 years after transplantation. So besides TB and fungal infection, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease was an important differential diagnosis considered. All factors which increased the cumulative immunosuppression in patients increase the risk of disseminated Cryptococcal disease. Presence of chronic liver disease and use of steroids, T cell depleting antibodies and Alemtuzumab are specifically associated with increased risk of Cryptococcosis. Calcineurin inhibitor based regimens are believed to be protective, being associated more commonly with Cryptococcosis limited to lungs with less likelihood of dissemination[5,6].

Our patient is HBsAg positive. But he had not received induction, had no history of rejection requiring pulse steroid therapy and has not been on MMF for 5 years. Though the apparent dose of immunosuppressive drugs given seems to be low, his cumulative immunosuppression level is definitely high as is suggested by the onset of late BKV associated nephropathy.

Cryptococcal infection commonly presents with neurologic disease (meningitis) or pneumonia. But it may also involve the skin and soft tissue, bones, joints and other organs like the liver and the kidney. Isolated pulmonary disease is uncommon seen in only 33% of the patients. Serum Cryptococcal antigen has 90% sensitivity in disseminated disease but may be negative in immunosuppressed patients especially with isolated pulmonary disease[5] as seen in our patient. The final diagnosis is by tissue biopsy and/or culture. The organism can be recognized by its oval shape, and narrow-based budding on histopathology. With the use of mucicarmine staining, the Cryptococcal capsule will stain rose to burgundy in color and help differentiate Cryptococcus neoformans from other yeasts, especially Blastomyces dermatiditis and Histoplasma capsulatum[5].

Choice of antifungal therapy depends on the severity and extent of the disease. In patients with severe pulmonary infection, neurological involvement and disseminated disease, combination of liposomal Amphotericin with Flucytosine for 2 wk followed by Fluconazole for 12 mo is recommended. If Flucytosine is not available, which was the case initially in our patient, Amphotericin should be given for a minimum of 4-6 wk[5].

Cryptococcal infection has an overall mortality of 14% in solid organ transplant recipients[6]. Early diagnosis and initiation of treatment is the key to survival. A high index of suspicion and step-wise approach to diagnosis including a lung biopsy is required as the duration of therapy differs significantly from other fungal infections.

A 40-year-old male renal transplant recipient presented with low grade fever and dry cough for one month.

A febrile patient with respiratory symptoms.

Chest infection-baterial/Tuberculosis/fungal.

Pancytopenia with high serum creatinine.

Non contrast computed tomography scan of chest showed bilateral, multiple, diffuse centrilobular and peribronchovascular cavitating nodules coalescing to form areas of consolidation with a larger cavity in apico posterior segment of upper lobe of left lung.

Biopsy from the lung lesion showed Cryptococcal infection and graft kidney biopsy showed BK virus associated nephropathy.

He was treated with liposomal Amphotericin and Flucytosine.

A renal transplant recipient may present with a cavitary lung lesion due to infection, malignancy (post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder) or inflammatory disease, though infections are the predominant causative factor.

Cryptococcal infection is the third most common fungal infection seen in transplant recipients. It commonly presents with neurologic disease (meningitis) or pneumonia, but may also involve the skin and soft tissue, bones, joints and other organs like the liver and the kidney.

Tissue biopsy or culture is required to diagnose isolated pulmonary cryptococcosis. Early diagnosis and initiation of treatment is essential for survival.

The case discusses an important issue in patients with kidney transplantation.

P- Reviewer: Ali-El-Dein B, Mahmoud KM, Sheashaa HA S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Gadkowski LB, Stout JE. Cavitary pulmonary disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:305-533, table of contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Küpeli E, Eyüboğlu FÖ, Haberal M. Pulmonary infections in transplant recipients. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2012;18:202-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chen M, Wang X, Yu X, Dai C, Chen D, Yu C, Xu X, Yao D, Yang L, Li Y. Pleural effusion as the initial clinical presentation in disseminated cryptococcosis and fungaemia: an unusual manifestation and a literature review. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Silveira FP, Husain S. Fungal infections in solid organ transplantation. Med Mycol. 2007;45:305-320. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Baddley JW, Forrest GN. Cryptococcosis in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13 Suppl 4:242-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Singh N, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, Dromer F, Gupta KL, John GT, del Busto R, Klintmalm GB, Somani J, Lyon GM. Cryptococcus neoformans in organ transplant recipients: impact of calcineurin-inhibitor agents on mortality. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:756-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |