Published online Jun 24, 2016. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v6.i2.442

Peer-review started: March 29, 2016

First decision: April 15, 2016

Revised: May 2, 2016

Accepted: May 17, 2016

Article in press: May 27, 2016

Published online: June 24, 2016

Processing time: 85 Days and 10.3 Hours

Kidney transplantation is the treatment of choice for a significant number of patients with end-stage renal disease. Although immunosuppression therapy improves graft and patient’s survival, it is a major risk factor for infection following kidney transplantation altering clinical manifestations of the infectious diseases and complicating both the diagnosis and management of renal transplant recipients (RTRs). Existing literature is very limited regarding osteomyelitis in RTRs. Sternoclavicular osteomyelitis is rare and has been mainly reported after contiguous spread of infection or direct traumatic seeding of the bacteria. We present an interesting case of acute, bacterial sternoclavicular osteomyelitis in a long-term RTR. Blood cultures were positive for Streptococcus mitis, while the portal entry site was not identified. Magnetic resonance imaging of the sternoclavicluar region and a three-phase bone scan were positive for sternoclavicular osteomyelitis. Eventually, the patient was successfully treated with Daptomycin as monotherapy. In the presence of immunosuppression, the transplant physician should always remain alert for opportunistic pathogens or unusual location of osteomyelitis.

Core tip: Although immunosuppression therapy improves kidney allograft and patient’s survival, it is a major risk factor for infection following kidney transplantation, altering the clinical manifestations of the infectious diseases and complicating both the diagnosis and management of renal transplant recipients (RTRs). Existing literature regarding osteomyelitis in RTRs is very limited while sternoclavicular osteomyelitis is a rare entity presenting with its own unique set of risk factors and complications. Infections caused by unconventional pathogens with unconventional infection sites are being increasingly diagnosed in RTRs and the physician should always remain alert when dealing with these patients.

- Citation: Dounousi E, Duni A, Xiromeriti S, Pappas C, Siamopoulos KC. Acute bacterial sternoclavicular osteomyelitis in a long-term renal transplant recipient. World J Transplant 2016; 6(2): 442-446

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v6/i2/442.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v6.i2.442

Kidney transplantation is the treatment of choice for a significant number of patients with end-stage renal disease. Renal transplant recipients (RTRs) benefit from a longer life expectancy and a better quality of life. Despite, recent accomplishments in the field of kidney transplantation, both short- and long-term medical complications still exist. Infectious diseases constitute one of the most common complications after kidney transplantation and the second most common cause of death among RTRs with a functioning graft[1]. Even though immunosuppressive therapy improves graft and patient survival, it has been reported that the increasing load of maintenance immunosuppression predisposes RTRs to clinically important infectious sequelae. The plethora, diversity and consequences of infectious complications in kidney transplantation have led to the accumulation of a growing amount of evidence describing the problem and trying at the same time to establish guidance for optimal management and support of these patients[1].

Existing literature comprises of a very small number of cases reporting osteomyelitis in RTRs. Traditional risk factors for osteomyelitis include trauma to the bone and trauma near a site of infection, the presence of sickle-cell disease, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, dialysis and related procedures, as well as immunosuppression. Most cases of osteomyelitis in adults are of hematogenous origin and primarily affect the spine[2]. The sternoclavicular joint is less commonly associated with osteomyelitis but presents its own unique set of risk factors and complications. We present a rare case of an adult long-term RTR who was diagnosed with acute, hematogenus sternoclavicular osteomyelitis due to streptococcus bacteremia whereas remarkably a portal entry site was not identified.

A 50-year-old male RTR, presented at the emergency department of our Tertiary University Hospital complaining about fever, chills and pain over the left sternoclavicular area, radiating to the shoulder and neck for the last two days. He denied any recent history of trauma, intravenous drug administration or dental procedure. Physical examination revealed pyrexia and marked tenderness over the left sternoclavicular area which appeared warm, red and swollen. Laboratory exams showed an elevated white blood cell count and C-reactive protein (Table 1), while the cervical spine and chest X-rays were unremarkable. The patient was directly admitted to the Renal Unit Ward and serial blood cultures were taken.

| At admission | On discharge | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.3 | 11.3 |

| WBC (/μL) | 11760 | 11900 |

| Neutro-Lympho-Mono (%) | 83-6-10 | 83-7-7 |

| PLT (/μL) | 163000 | 290000 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 41 | 15 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 130 | 17 |

| eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2) | 36 | 40 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 86 | 76 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 136 | 139 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.2 | 4.3 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 75 | 80 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 3.9 | 2.7 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 3.4 | 3.4 |

The patient was a long-term RTR regularly followed up at the renal transplant outpatient clinic (OC) of our Hospital during the last year. On his last visit a month ago, he was asymptomatic with unremarkable clinical findings and stable renal function, with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 41 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation). Maintenance immunosuppression therapy included cyclosporine (75 mg bid, C2 levels of 436 ng/mL), mycophenolate mofetil (1 g bid) as well as prednisolone (5 mg qd). The patients was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology more than twenty years ago, was treated with hemodialysis for approximately 7 years and subsequently received a renal allograft from a cadaveric donor 14 years ago. Three months after the transplantation, the patient had suffered an acute rejection episode, which was successfully treated with intravenous pulses of steroids. The rest current medical history included well controlled arterial hypertension (antihypertensive treatment: Amlodipine 10 mg qd) and hip osteopenia diagnosed by a Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan (DEXA) (Alfacalcidol 0.25 μg qd).

Immediately after admission, imaging of the sternoclavicular area excluded the presence of a fluid collection that could be aspirated. Considering the patient’s clinical findings and his long-term immunocompromised status, empirical treatment for septic arthritis with Vancomycin (dose adjusted to eGFR) and Ciprofloxacin was commenced. Further diagnostic workup included a dental examination which did not reveal a possible portal entry site for the bacteria. Abdominal ultrasound findings were unremarkable while ultrasound of the renal allograft was within normal. Urine cultures were negative. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed mild mitral regurgitation and calcifications of the aortic cusps and mitral annulus. A transesophageal ultrasound was subsequently performed, ruling out concomitant endocarditis.

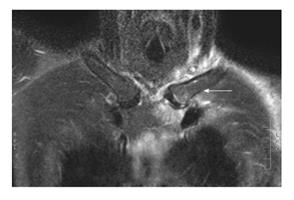

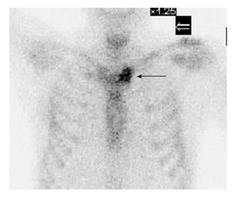

All blood cultures became positive within 48 h for Streptococcus mitis (Viridans group streptococcus) with a good sensitivity profile, including Glycopeptides (Vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration < 1 mg/L) and Daptomycin. Vancomycin treatment, targeting trough blood levels of 15-20 mg/L, was continued whereas Ciprofloxacin was stopped. In order to further evaluate the sternoclavicular joint and differentiate between septic arthritis and osteomyelitis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (no gadolinium administration) of the region was performed. The MRI showed bone edema of the left intraarticular surface of the sternum and the clavicle together with soft tissue edema, findings suggestive of acute sternoclavicular osteomyelitis (Figure 1). No intraarticular fluid collection was observed. A three-phase whole body bone scan (technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate) was subsequently performed, which showed focally intense, increased activity over the left sternoclavicular area, a finding positive for osteomyelitis (Figure 2).

A week from admission the patient continued to have low grade fever and was dependent on analgesics for pain control, despite achieving adequate Vancomycin trough levels. Considering the diagnosis of acute bacterial osteomyelitis with an unconventional location, the patient’s clinical course, the need of long-term intravenous antibiotic treatment, the difficulties of Vancomycin treatment (monitoring levels and possible related nephrotoxicy) and practical issues (patient’s residence was far from the hospital), the decision of switching antimicrobial treatment to Daptomycin as monotherapy (dose 4 mg/kg per 24 h) was taken. The patient became afebrile within a few days, inflammatory markers gradually declined and his physical status progressively improved (Table 1). No surgical debridement was performed as there was no evidence of a soft tissue abscess or subperiosteal collection, and no concomitant joint infection was diagnosed. The patient was discharged from the hospital a fortnight after admission, with recommendations for continuation of antimicrobial treatment for a total period of 6 wk and close medical follow-up at the renal transplant OC.

The patient remains asymptomatic and with preserved renal function six months after the completion of the antimicrobial treatment.

In the modern era of renal transplantation infectious diseases remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality in RTRs[1]. The introduction of new immunosuppressant agents in renal transplantation along with the increasing resistance of pathogens to antimicrobial agents worldwide are partially responsible for the emergence of rare infectious clinical cases which constitute a major challenge for the transplant clinicians. Here, we report an interesting, noteworthy case of acute bacterial sternoclavicular osteomyelitis in a long-term adult RTR, with no portal entry site for the bacteria which was successfully treated with Daptomycin as monotherapy.

In general, traditional risk factors for osteomyelitis include trauma to the bone and trauma near a site of infection, the presence of sickle-cell disease, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, dialysis and related procedures, as well as immunosuppression. Most cases of osteomyelitis in adults are of hematogenous origin and primarily affect the spine[2]. The clavicle contains scanty red marrow and sparse vascular supply. It is an exceedingly rare site for osteomyelitis, especially of hematogenous origin[3]. Clavicular osteomyelitis is rare and has been mainly reported after contiguous spread of infection or direct traumatic seeding of the bacteria[4]. Thus, there are reports in the literature of sternoclavicular osteomyelitis following central line placement[5], major head and neck surgery and radiation therapy to head and neck tumors[6]. Intravenous drug abusers are an especially high risk group for clavicular osteomyelitis and septic arthritis[7].

With regard to the responsible pathogens, S. aureus is the most commonly isolated organism in most types of osteomyelitis, affecting 50%-70% of cases, while other gram positive cocci and gram negative bacilli are identified less often, accounting for approximately 20%-25% of acute osteomyelitis cases respectively[8,9]. Treatment of osteomyelitis requires prolonged antimicrobial therapy and frequently adjunctive surgical therapy for the debridement of necrotic material in order to eradicate the infection. Antibiotic therapy should be adjusted to culture and susceptibility results. If culture results are not obtainable, broad spectrum empiric therapy, including Vancomycin together with an agent with activity against gram negative organisms, should be administered[10-12].

Regarding selection of antimicrobial treatment in our patient, Daptomycin was finally chosen as it has exhibited activity in the treatment of gram positive bone and joint infections[13]. It is rapidly bactericidal and appears effective against multidrug-resistant gram positive pathogens, commonly found in osteomyelitis and joint infections, even when other first-line antibacterial treatments have failed[14-16]. Daptomycin is well tolerated; it has a relatively safe side effect profile, no interactions with calcineurin inhibitors, and a low risk of spontaneous resistance. The mode of action, rapid in vitro bactericidal activity against growing and stationary-phase bacteria, a once-daily dosing regimen, and no requirement for drug monitoring contribute to its potential therapeutic utility[17].

Existing literature comprises of a very small number of cases reporting osteomyelitis in RTRs, which involve locations such as the ankle, the symphysis pubis or the vertebral column[13,18-21], whereas there are no reports in the literature regarding sternoclavicular osteomyelitis in RTRs. The additive effect of long-term immunosuppresion treatment and possibly osteopenia (although previous routine DEXA scans revealed only hip localized osteopenia) rendered our patient among patients’ subgroups with increased risk for osteomyelitis. Remarkably, a portal entry site for the bacteremia was not identified. Finally, the sternoclavicular bone was the solitary site of infection as demonstrated from the imaging studies.

Considering the immune suppressed status as a predisposing factor for infections as well as the growing number of RTRs, we might come across more cases of unconventional pathogens and sites of infection in the future[22]. Prevention, vigilance and deep knowledge of the diagnostic and therapeutic management of infections could potentially mitigate the consequences for RTRs.

A 50-year-old male renal transplant recipient complained about fever, chills and pain over the left sternoclavicular area, radiating to the shoulder and neck for the last two days.

Physical examination revealed pyrexia and marked tenderness over the left sternoclavicular area which appeared warm, red and swollen.

Differential diagnosis was between septic arthritis and osteomyelitis.

Laboratory exams showed an elevated white blood cell count and C-reactive protein and all blood cultures became positive within 48 h for Streptococcus mitis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (no gadolinium administration) of the region showed bone edema of the left intraarticular surface of the sternum and the clavicle together with soft tissue edema, without intraarticular fluid collection and a three-phase whole body bone scan [technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate (99Tc-MDP)] showed focally intense, increased activity over the left sternoclavicular area, findings positive for osteomyelitis.

Empirical treatment for septic arthritis with Vancomycin and Ciprofloxacin was commenced and subsequently switched to treatment with Daptomycin as monotherapy.

Clavicular osteomyelitis is rare and has been mainly reported after contiguous spread of infection or direct traumatic seeding of the bacteria as occurs following central line placement, major head and neck surgery and radiation therapy to head and neck tumors.

A three-phase whole body bone scan is a 99Tc-MDP based diagnostic test is used in nuclear medicine in order to detect different types of pathology in the bones. The three phases are the flow phase, the blood pool image and the delayed phase. Differential diagnosis is based on differential image processing from the three phases; Calcineurin inhibitors: Cyclosporine and Tacrolimus - are a class of immunosuppressive drugs which are used as first line agents for maintenance therapy after kidney transplantation.

Considering the immune suppressed status as a predisposing factor for infections as well as the growing number of renal transplant recipients, the authors might come across more cases of unconventional pathogens and sites of infection in the future.

The authors describe a very unusual complication occurring late after renal transplantation. The case report is well written and useful for the reader just bacause of the unusual complication.

P- Reviewer: Guerado E, Mu JS, Shrestha BM, Salvadori M S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Green M. Introduction: Infections in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13 Suppl 4:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004;364:369-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1313] [Cited by in RCA: 1369] [Article Influence: 65.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Suresh S, Saifuddin A. Unveiling the ‘unique bone’: a study of the distribution of focal clavicular lesions. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:749-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gerscovich EO, Greenspan A. Osteomyelitis of the clavicle: clinical, radiologic, and bacteriologic findings in ten patients. Skeletal Radiol. 1994;23:205-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Peces R, Díaz-Corte C, Baltar J, Gago E, Alvarez-Grande J. A desperate case of failing vascular access--management of superior vena cava thrombosis, recurrent bacteraemia, and acute clavicular osteomyelitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:487-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Burns P, Sheahan P, Doody J, Kinsella J. Clavicular osteomyelitis: a rare complication of head and neck cancer surgery. Head Neck. 2008;30:1124-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Beals RK, Sauser DD. Nontraumatic disorders of the clavicle. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:205-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gerszten E, Allison MJ, Dalton HP. An epidemiologic study of 100 consecutive cases of osteomyelitis. South Med J. 1970;63:365-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Prieto-Pérez L, Pérez-Tanoira R, Petkova-Saiz E, Pérez-Jorge C, Lopez-Rodriguez C, Alvarez-Alvarez B, Polo-Sabau J, Esteban J. Osteomyelitis: a descriptive study. Clin Orthop Surg. 2014;6:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lazzarini L, Lipsky BA, Mader JT. Antibiotic treatment of osteomyelitis: what have we learned from 30 years of clinical trials? Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:127-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, Kaplan SL, Karchmer AW, Levine DP, Murray BE. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:285-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1171] [Cited by in RCA: 1247] [Article Influence: 89.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Muesse JL, Blackmon SH, Ellsworth WA, Kim MP. Treatment of sternoclavicular joint osteomyelitis with debridement and delayed resection with muscle flap coverage improves outcomes. Surg Res Pract. 2014;2014:747315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Polilli E, Ursini T, Mazzotta E, Sozio F, Savini V, D’Antonio D, Barbato M, Consorte A, Parruti G. Successful salvage therapy with Daptomycin for osteomyelitis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a renal transplant recipient with Fabry-Anderson disease. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2012;11:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rice DA, Mendez-Vigo L. Daptomycin in bone and joint infections: a review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:1495-1504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liang SY, Khair HN, McDonald JR, Babcock HM, Marschall J. Daptomycin versus vancomycin for osteoarticular infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): a nested case-control study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:659-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Seaton RA, Malizos KN, Viale P, Gargalianos-Kakolyris P, Santantonio T, Petrelli E, Pathan R, Heep M, Chaves RL. Daptomycin use in patients with osteomyelitis: a preliminary report from the EU-CORE(SM) database. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:1642-1649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kielstein JT, Eugbers C, Bode-Boeger SM, Martens-Lobenhoffer J, Haller H, Joukhadar C, Traunmüller F, Knitsch W, Hafer C, Burkhardt O. Dosing of daptomycin in intensive care unit patients with acute kidney injury undergoing extended dialysis--a pharmacokinetic study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1537-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ersoy A, Akdag I, Akalin H, Sarisozen B, Ener B. Aspergillosis osteomyelitis and joint infection in a renal transplant recipient. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:1662-1663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jindal RM, Idelson B, Bernard D, Cho SI. Osteomyelitis of symphysis pubis following renal transplantation. Postgrad Med J. 1993;69:742-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Valson AT, David VG, Balaji V, John GT. Multifocal bacterial osteomyelitis in a renal allograft recipient following urosepsis. Indian J Nephrol. 2014;24:189-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Novak RM, Polisky EL, Janda WM, Libertin CR. Osteomyelitis caused by Rhodococcus equi in a renal transplant recipient. Infection. 1988;16:186-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |