Published online Jun 24, 2016. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v6.i2.437

Peer-review started: February 14, 2016

First decision: March 1, 2016

Revised: April 4, 2016

Accepted: April 21, 2016

Article in press: April 22, 2016

Published online: June 24, 2016

Processing time: 140 Days and 12.6 Hours

Total pancreatectomy and islet auto transplantation is a good option for chronic pancreatitis patients who suffer from significant pain, poor quality of life, and the potential of type 3C diabetes and pancreatic cancer. Portal vein thrombosis is the most feared complication of the surgery and chances are increased if the patient has a hypercoagulable disorder. We present a challenging case of islet auto transplantation from our institution. A 29-year-old woman with plasminogen activator inhibitor-4G/4G variant and a clinical history of venous thrombosis was successfully managed with a precise peri- and post-operative anticoagulation protocol. In this paper we discuss the anti-coagulation protocol for safely and successfully caring out islet transplantation and associated risks and benefits.

Core tip: Total pancreatectomy and islet auto-transplantation is an option for select patients with chronic pancreatitis. Portal vein thrombosis is the most feared surgical complication and chances are increased if the patient has a hypercoagulable disorder. The paper describes important topics like the management of the anticoagulation in the peri-operative period.

- Citation: Desai CS, Khan KM, Cui W. Islet autotransplantation in a patient with hypercoagulable disorder. World J Transplant 2016; 6(2): 437-441

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v6/i2/437.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v6.i2.437

Patients with chronic pancreatitis suffer from significant pain and associated decrease in the quality of life and also a potential of forming type 3C diabetes and the pancreatic cancers[1-4]. It is an inflammatory disease, which is characterized by irreversible, morphological changes that cause permanent loss of function, and fibrosis and development of severe pain and complications. Over time, fibrosis in the pancreas, results in destruction of the islet cells, and patients are at risk of diabetes[1,3,4]. The risk of pancreatic cancer is 10 to 15 fold higher in chronic pancreatitis patients and if it is associated with hereditary pancreatitis with genetic mutations, then the lifetime risk is 75%[2,5]. Many surgical, medical, endoscopic and intervention radiological treatments are applied to these patients, despite which many still suffer from continuous dependence on narcotics and bad quality of life.

Removal of the pancreas followed by autologous islet cell transplantation is a great option for selected patients with chronic pancreatitis[6-14]. Islet auto transplantation helps to take care of 3 Ps that are necessary for this disorder: (1) Pain relief; (2) Prevention of the brittle diabetes mellitus; and (3) Prevention of pancreatic cancer[15]. At times, the results of the autologous islet cell transplantation are criticized because the variable insulin independence rate reported[16,17]. We have previously argued that the insulin independence is not the only marker of the success, the wide marker of the success would be euglycemia, preventing cancer and having better quality of life[15].

Good outcomes of islet auto transplantation are based on various factors from selection of the case to performing safe surgery, good isolation and safe injection of the cells followed by good engraftment of the islet cells. Once the islets are isolated and brought back to the patient, a small angiocatheter is introduced in one of the vessels either the splenic vein stump or any vessels draining into the superior mesenteric vein to infuse these cells into the portal vein so that they can flow to the liver. Safety is important in terms of decreasing the risk of thrombogenesis in these vessels by paying attention to the details of the procedure, the physiology of the patient, and the liver pathology[18]. Surgical complications are most dreaded compared to the long-term outcome and insulin dependency because they can add to significant morbidity and therefore poor quality of life to the patient. Porto-venous thrombosis would arguably be the most important complication. It can vary in magnitude from a segmental vein to thrombosis of the main portal vein and potentially complete thrombosis of the superior mesenteric access requiring a bowel resection and consequent problems[19,20]. The risk of portal vein thrombosis will be increased if the patient has a hypercoagulable disorder.

We report a case from our new program with physiological challenge in the context of issues described. These include a case of islet autotransplantation performed in a patient with a hypercoagulable disorder. To our knowledge, it is the first such case in the literature.

The patient was a 29-year-old lady (body weight 83 kg, body mass index 29.3 kg/m2) with a history of chronic abdominal pain related to chronic pancreatitis. At the time of her initial visit she was in the emergency room or hospitalized on a weekly basis. Her history dated back 13 years and she had been on narcotics for 6 years. She had undergone 7 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographys over the years and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) had shown pancreas divisum. Our own MRI scoring system[21] indicated minimal pancreatic damage (atrophy, 1/6). The pre-operative C-peptide was 1.75 ng/mL and hemoglobin A1c was 5.5%. We also considered gall stone disease, alcohol and completed a genetic analysis for common hereditary gene mutations that are causally associated with chronic pancreatitis. She had also reported having developed thrombosis related to PICC line placement on multiple occasions at an outside institution. During her evaluation we obtained hypercoagulability studies, which included factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin gene mutation, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) gene mutation and level, clotting factor VII, protein C, protein S levels, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene mutations and an autoimmune thrombophilia screen. She was found to be homozygous for the 4G variant of the PAI-1 gene and heterozygote for the MTHFR A1298C.

Her surgery was performed using the technique described earlier[22] and islet infusion was also done through splenic vein stump. Islet preparation was performed at the current good manufacturing practice facility in the Islet Cell Laboratory at the Georgetown University Hospital.

The pancreas was explanted post 1 and half min of warm ischemia time and placed immediately into an ice-cold Viaspan solution in a sterile container and delivered to the lab on ice. On arrival of the lab, the pancreatic duct was cannulated after trimming. The pancreas was then divided into two portions at the neck. On the cut surface both openings of the pancreatic duct were cannulated with a 14-gauge cannula. An enzyme solution containing collagenase HA and Thermolysin (Vitacyte, Indiana, United States) was infused into the pancreas through the cannula and connected with a 60 cc syringe through an extension tube. In addition, the parenchyma was then repeatedly injected with the enzyme solution using a 60 cc syringe. The thoroughly distended pancreas was then digested using the semi-automated method of Ricordi[23]. The pancreas weighed 65.9 g. The total cold ischemia time from removal of the pancreas to completion of trimming was 51 min. The digestion rate was 92.2% post 18 min of digestion. After purification using a modified continuous density gradient method with cell processor COBE2991[24], the final pellet was reduced from 36 to 12 mL[25]. The total islet yield was 459164 islet equivalents (IEQ) which was quantified as IEQ by normalizing the islet mass to an islet size of 150 μm diameter. The islet recovery was 7552 IEQ/g of pancreas tissue. The final pellet was suspended in the transplantation media (5% human serum albumin) containing 35 units of Heparin per kilogram of patient body weight. In total, 5532 IEQ per kilogram recipient body weight (IEQ/kg) of islets were available.

The islet infusion in to the liver involved a venous catheter placed in a splenic vein stump and advanced intravenously towards the portal vein. In order to reduce complication rates of acute portal hypertension and thrombosis in this case at the most, low-volume (12 mL pellet) prepared through purification procedure, was infused. We gave the patient 35 U/kg intravenously in addition to the 35 U/kg of Heparin along with islet infusion; the patient therefore received a total dose of 70 U/kg of heparin. Portal pressures were closely monitored during infusion, because of an established tenfold (1.52%-15.2%) increase in the risk of thrombosis with portal pressure changes above 25 cm H2O[25]. The pre infusion portal pressure was 4.5 cm/saline and the post infusion pressure was 15 cm/saline.

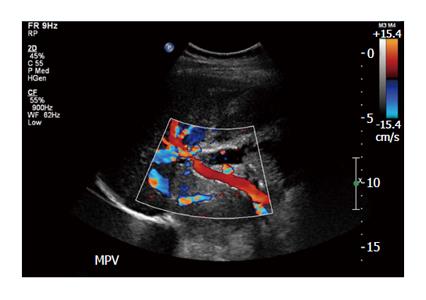

Heparin was started intra-operatively. Fifty IU/kg of body weight bolus before the infusion of islet cells followed by 25000 IU mixed with 500 mL of D5 1/2 normal saline at the rate of 10 IU/kg per hour. Postoperatively, the patient was continued on a heparin drip according to our protocol and activated thromboplastin time was maintained in the range of 50 to 60 s. At the end of three days when she started on clear liquid diet, we continued the patient on low molecular weight heparin and monitored with anti-Xa activity factors maintained between 0.6 to 1 international units/mL. Postoperative Doppler ultrasound of the liver was performed on day 1, 2 and 5 and once weekly for one month and biweekly for another two months. Specifically, the doppler studies during the first week demonstrated patency and normal flow in the portal veins, hepatic arteries and veins; the main portal vein peak velocities ranged between 25-38 cm/s, left and right portal vein velocities ranged from 11-27 cm/s (Figure 1). The patient was discharge home after 14 d. At three months the patient was off insulin with a C-peptide of 1.95 ng/mL. At the end of three months, the dose of low molecular weight heparin was reduced to maintain anti-Xa level between 0.3 to 0.6 international units/mL. Six months after the surgery, the low molecular weight heparin was discontinued after consultation with hematology. The patient did not develop venous thrombosis of any form during follow-up and was able to resume a normal life.

Total pancreatectomy and islet auto transplantation has been described by some as a radical option though it has a clear role for patients with chronic pancreatitis. Patients undergo multiple endoscopic procedures and fail to get a satisfactory outcome and all the time their narcotic requirement keeps escalating. This definitive procedure is feared because of surgical complications like portal vein thrombosis and also the failure of the islets to prevent diabetes.

Hypercoagulability is a significant risk factor for portal vein thrombosis. In one study 28% of patients with portal vein thrombosis had an inherited thrombophilic disorder[26]. Of this factor V Leiden mutation was the most common (11%) followed by anti-thrombin III deficiency (11%) and protein c deficiency (8%). Prothrombin gene mutations are also commonly implicated in venous thrombosis[27]. The PAI 4G variant and MTHFR mutations are considered less severe though do have an increased risk for venous thrombosis after major surgery including transplantation. Such situations are challenging because of the post-operative risk of thrombosis leading to graft failure or bleeding from anti-coagulation. However, many such transplants are carried out in a safe manner. Our patient had a PAI-1 gene mutation, which was only diagnosed after diligent history taking helped us to obtain the risk in this case. The authors have previously worked at different auto islet cell transplantation centers and as with other surgeries it was not routine to do a hypercoagulable workup since obtaining this panel in every patient is very expensive and may not be cost effective[15,18,22].

Portal vein thrombosis after islet auto-transplant though uncommon, can be risky and life threatening. There are few previous individual reports of portal vein thrombosis after islet auto-transplantation[20] and one series that indicated a prevalence of 3.7% after clinical islet transplantation[28]. There is however no systematic study of the cause of thrombosis in such cases. In a previous publication we have noted that there may be unrecognized mild fibrosis and or steatosis[18]. We were however unable to show that any specific histologic pattern was more susceptible to venous thrombus formation. To prevent portal venous thrombosis in patients such as ours above with pre-existing risk factors it is imperative to identify at risk patients and manage these patients with therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin. Heparin also has advantage in the islet engraftment process and hence it has dual advantage, but has a significant risk of post-operative bleeding and hence it is very important that the surgery is performed with good hemostasis. Heparin is given by almost all the centers performing auto-islet cell transplant to their patients. However, there are no consensus guidelines on the amount and duration it needs to given. We adapted an approach in which we start a heparin drip in operating room at the time of starting islet infusion after giving bolus. It is continued for the next three days maintaining the activated thromboplastin time in the range of 50 to 60 s. At the end of three days when the patient starts taking clears, we continue with low molecular weight heparin two times a day dose based on patient’s weight with anti-Xa activity factors maintained between 0.6 to 1 international units/mL. Patient’s postoperative Doppler ultrasound on the liver is done on postoperative day 1, 2 and 5 and subsequently was done once weekly for one month and then twice weekly for another two months if they are at high risk. High risk is defined by three main factor: (1) hypercoagulable disorder; (2) previous history of deep venous thrombosis other than segmental splenic vein thrombosis related to chronic pancreatitis (even if the hypercoagulable panel is normal); and (3) high portal pressure after infusion (more than 25 cm of saline). If the patient is high risk then at the end of three months, low molecular weight heparin dose is reduced to maintain anti-Xa level to be between 0.3 to 0.6 international units/mL. Six months after the surgery, the low molecular weight heparin is discontinued after consultation with hematology. If the patient is not at high risk then after two weeks dose is reduced and then stopped after another two weeks.

In summary, islet auto transplantation in itself is a challenging procedure and even more challenges can arise medically if there are physiological challenges like a hypercoagulable disorder. Despite all these challenges with careful teamwork and experience, these patients can be safely managed.

Islet auto transplantation is a challenging procedure and even more challenges can arise medically; if there are physiological challenges like a hypercoagulable disorder. Despite all these challenges with careful teamwork and experience, these patients can be safely managed.

Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation complicated by primary hypercoagulability that presented as repeated thrombosis of indwelling venous lines.

The presentation was characterized by symptoms of chronic pancreatitis and a history of deep venous thrombosis.

An alternative explanation to a primary hypercoagulability to account for thrombosis if intravenous lines would be that the presence of intravenous lines themselves was the cause of catheter thrombosis.

Screening for hypercoagulability included plasma proteins, genetic defects and autoimmunity as potential causes of thrombosis with the patient having a plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 variant.

Serial ultrasounds were used to monitor for portal vein thrombosis after islet infusion in to the portal vein after total pancreatectomy.

Confirmation of chronic pancreatitis as the cause for abdominal pain.

Heparin infusion followed by low molecular weight heparin and aspirin as prophylaxis for a prothrombotic state.

There are previous cases of a hypercoagulability giving rise to deep venous thrombosis, most notably with factor V Leiden mutation.

Hypercoagulability refers to a pathological increase in the tendency to form intravascular clots. Patients undergoing major intraabdominal operations should be screened for a hypercoagulable state if there is any history of abnormal venous clot formation.

This a successful case of islet autotransplantation performed in a chronic pancreatitis patient suffered from significant pain with a hypercoagulable disorder. It is imperative to identify at risk patients and manage these patients with therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin to prevent portal venous thrombosis in patients with pre-existing risk factors. The author’s careful teamwork and experience is helpful for safely managing these patients.

P- Reviewer: Fu D, Kin T, Kleeff J S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Chen WX, Zhang WF, Li B, Lin HJ, Zhang X, Chen HT, Gu ZY, Li YM. Clinical manifestations of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5:133-137. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Freelove R, Walling AD. Pancreatic cancer: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73:485-492. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Malka D, Hammel P, Sauvanet A, Rufat P, O’Toole D, Bardet P, Belghiti J, Bernades P, Ruszniewski P, Lévy P. Risk factors for diabetes mellitus in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1324-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schneider A, Whitcomb DC. Hereditary pancreatitis: a model for inflammatory diseases of the pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:347-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, DiMagno EP, Elitsur Y, Gates LK, Perrault J, Whitcomb DC. Hereditary pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Hereditary Pancreatitis Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:442-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 609] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kesseli SJ, Smith KA, Gardner TB. Total pancreatectomy with islet autologous transplantation: the cure for chronic pancreatitis? Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6:e73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Witkowski P, Savari O, Matthews JB. Islet autotransplantation and total pancreatectomy. Adv Surg. 2014;48:223-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bellin MD, Freeman ML, Gelrud A, Slivka A, Clavel A, Humar A, Schwarzenberg SJ, Lowe ME, Rickels MR, Whitcomb DC. Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation in chronic pancreatitis: recommendations from PancreasFest. Pancreatology. 2014;14:27-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Robertson GS, Dennison AR, Johnson PR, London NJ. A review of pancreatic islet autotransplantation. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:226-235. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Balamurugan AN, Loganathan G, Bellin MD, Wilhelm JJ, Harmon J, Anazawa T, Soltani SM, Radosevich DM, Yuasa T, Tiwari M. A new enzyme mixture to increase the yield and transplant rate of autologous and allogeneic human islet products. Transplantation. 2012;93:693-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bellin MD, Sutherland DE, Beilman GJ, Hong-McAtee I, Balamurugan AN, Hering BJ, Moran A. Similar islet function in islet allotransplant and autotransplant recipients, despite lower islet mass in autotransplants. Transplantation. 2011;91:367-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Robertson RP, Lanz KJ, Sutherland DE, Kendall DM. Prevention of diabetes for up to 13 years by autoislet transplantation after pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis. Diabetes. 2001;50:47-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Najarian JS, Sutherland DE, Baumgartner D, Burke B, Rynasiewicz JJ, Matas AJ, Goetz FC. Total or near total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1980;192:526-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sutherland DE, Matas AJ, Goetz FC, Najarian JS. Transplantation of dispersed pancreatic islet tissue in humans: autografts and allografts. Diabetes. 1980;29 Suppl 1:31-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Desai CS, Khan KM, Cui WX. Total pancreatectomy-autologous islet cell transplantation (tp-ait) for chronic pancreatitis-what defines success? CellR4. 2015;3:e1536. |

| 16. | Sutherland DE, Gruessner AC, Carlson AM, Blondet JJ, Balamurugan AN, Reigstad KF, Beilman GJ, Bellin MD, Hering BJ. Islet autotransplant outcomes after total pancreatectomy: a contrast to islet allograft outcomes. Transplantation. 2008;86:1799-1802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wilson GC, Sutton JM, Abbott DE, Smith MT, Lowy AM, Matthews JB, Rilo HL, Schmulewitz N, Salehi M, Choe K. Long-term outcomes after total pancreatectomy and islet cell autotransplantation: is it a durable operation? Ann Surg. 2014;260:659-665; discussion 665-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Desai CS, Khan KM, Megawa FB, Rilo H, Jie T, Gruessner A, Gruessner R. Influence of liver histopathology on transaminitis following total pancreatectomy and autologous islet transplantation. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1349-1354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Thomas RM, Ahmad SA. Management of acute post-operative portal venous thrombosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:570-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Memsic L, Busuttil RW, Traverso LW. Bleeding esophageal varices and portal vein thrombosis after pancreatic mixed-cell autotransplantation. Surgery. 1984;95:238-242. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Khan KM, Desai CS, Kalb B, Patel C, Grigsby BM, Jie T, Gruessner RW, Rodriguez-Rilo H. MRI prediction of islet yield for autologous transplantation after total pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1116-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Desai CS, Stephenson DA, Khan KM, Jie T, Gruessner AC, Rilo HL, Gruessner RW. Novel technique of total pancreatectomy before autologous islet transplants in chronic pancreatitis patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:e29-e34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ricordi C, Finke EH, Dye ES, Socci C, Lacy PE. Automated isolation of mouse pancreatic islets. Transplantation. 1988;46:455-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Anazawa T, Matsumoto S, Yonekawa Y, Loganathan G, Wilhelm JJ, Soltani SM, Papas KK, Sutherland DE, Hering BJ, Balamurugan AN. Prediction of pancreatic tissue densities by an analytical test gradient system before purification maximizes human islet recovery for islet autotransplantation/allotransplantation. Transplantation. 2011;91:508-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wilhelm JJ, Bellin MD, Dunn TB, Balamurugan AN, Pruett TL, Radosevich DM, Chinnakotla S, Schwarzenberg SJ, Freeman ML, Hering BJ. Proposed thresholds for pancreatic tissue volume for safe intraportal islet autotransplantation after total pancreatectomy. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:3183-3191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dutta AK, Chacko A, George B, Joseph JA, Nair SC, Mathews V. Risk factors of thrombosis in abdominal veins. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4518-4522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ, Zivelin A, Arruda VR, Aiach M, Siscovick DS, Hillarp A, Watzke HH, Bernardi F, Cumming AM. Geographic distribution of the 20210 G to A prothrombin variant. Thromb Haemost. 1998;79:706-708. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Kawahara T, Kin T, Kashkoush S, Gala-Lopez B, Bigam DL, Kneteman NM, Koh A, Senior PA, Shapiro AM. Portal vein thrombosis is a potentially preventable complication in clinical islet transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2700-2707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |