Published online Sep 24, 2015. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v5.i3.102

Peer-review started: February 26, 2015

First decision: June 3, 2015

Revised: June 11, 2015

Accepted: August 13, 2015

Article in press: August 14, 2015

Published online: September 24, 2015

Processing time: 212 Days and 17.1 Hours

AIM: To evaluate whether there is a threshold sensitization level beyond which benefits of chronic steroid maintenance (CSM) emerge.

METHODS: Using Organ Procurement and Transplant Network/United Network of Organ Sharing database, we compared the adjusted graft and patient survivals for CSM vs early steroid withdrawal (ESW) among patients who underwent deceased-donor kidney (DDK) transplantation from 2000 to 2008 who were stratified by peak-panel reactive antibody (peak-PRA) titers (0%-30%, 31%-60% and > 60%). All patients received perioperative induction therapy and maintenance immunosuppression based on calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF).

RESULTS: The study included 42851 patients. In the 0%-30% peak-PRA class, adjusted over-all graft-failure (HR 1.11, 95%CI: 1.03-1.20, P = 0.009) and patient-death (HR 1.29, 95%CI: 1.16-1.43, P < 0.001) risks were higher and death-censored graft-failure risk (HR 1.06, 95%CI: 0.98-1.14, P = 0.16) similar for CSM (n = 25218) vs ESW (n = 7399). Over-all (HR 1.04, 95%CI: 0.85-1.28, P = 0.70) and death-censored (HR 0.97, 95%CI: 0.78-1.21, P = 0.81) graft-failure risks were similar and patient-death risk (HR 1.39, 95%CI: 1.03-1.87, P = 0.03) higher for CSM (n = 3495) vs ESW (n = 850) groups for 31%-60% peak-PRA class. In the > 60% peak-PRA class, adjusted overall graft-failure (HR 0.90, 95%CI: 0.76-1.08, P = 0.25) and patient-death (HR 0.92, 95%CI: 0.71-1.17, P = 0.47) risks were similar and death-censored graft-failure risk lower (HR 0.84, 95%CI: 0.71-0.99, P = 0.04) for CSM (n = 4966) vs ESW (n = 923).

CONCLUSION: In DDK transplant recipients who underwent perioperative induction and CNI/MMF maintenance, CSM appears to be associated with increased risk for death with functioning graft in minimally-sensitized patients and improved death-censored graft survival in highly-sensitized patients.

Core tip: This study critically evaluated the role of steroid maintenance in kidney transplant recipients (KTR) based on the level of sensitization by utilizing the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network/United Network of Organ Sharing database. In the multivariate model, we found an association between increased risk for death with functioning graft and steroid maintenance in KTRs who had peak-panel reactive antibody < 30% and received perioperative induction therapy followed by calcineurin inhibitor/mycophenolate mofetil maintenance. On the other hand, steroid maintenance was associated with improved death-censored graft survival without adversely impacting patient survival in KTRs with a peak PRA > 60%. No benefits of steroid maintenance were observed in older KTRs regardless of level of sensitization. These finding have clinical relevance and should be further evaluated in randomized clinical trials.

- Citation: Sureshkumar KK, Marcus RJ, Chopra B. Role of steroid maintenance in sensitized kidney transplant recipients. World J Transplant 2015; 5(3): 102-109

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v5/i3/102.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v5.i3.102

Historically, corticosteroid has enjoyed a pivotal role in maintenance immunosuppression in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs). Chronic steroid therapy can worsen hypertension and dyslipidemia, as well as contribute to the development of new onset diabetes mellitus, all risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Steroid therapy makes patients prone to infections and accelerated bone loss. Routine use of induction therapy along with the availability of more potent immunosuppressive agents such as tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) has enabled transplant professionals to utilize early steroid withdrawal (ESW) in KTRs. The concern with ESW includes increased risk of acute rejection which might adversely impact graft outcomes. Current data suggest that corticosteroids could be discontinued safely during the first week after transplantation in patients who are at low immunological risk and receive induction therapy[1]. Studies of ESW have shown outcomes comparable to steroid maintenance regimens[2-11]. A recent registry analysis showed that the percentage of KTRs discharged from the initial transplant admission on a steroid-free maintenance immunosuppression increased from 3.7% in the year 2000 to 32.5% as of 2006[12].

Patients who develop anti-human leukocyte antigen (anti-HLA) antibodies due to factors such as prior pregnancy, blood transfusion or previous transplant rejection are generally considered immunologically high risk and many transplant centers keep these sensitized patients on a steroid maintenance immunosuppressive protocol in the hopes of reducing the risk for acute rejection. It is not clear whether there is a threshold level of sensitization at which the beneficial effects of steroid maintenance begin to emerge in such patients. We aimed to compare the outcomes for steroid vs no steroid addition to a calcineurine inhibitor (CNI)/MMF based regimen in patients who underwent deceased donor kidney (DDK) transplantation after receiving peri-operativevinduction therapy and stratified by the level of peak panel reactive antibody (peak-PRA) titer.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down by the Declaration of Helsinki as well as Declaration of Istanbul. Using Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN)/United Network of Organ Sharing database, we identified patients ≥ 18 years who underwent a DDK transplantation between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2008 after receiving antibody induction therapy with rabbit- antithymocyte globulin (r-ATG), alemtuzumab or an interleukine-2 receptor blocker agent (IL-2R, basiliximab or daclizumab) and discharged on a CNI/MMF based maintenance immunosuppression regimen with or without steroids. Prednisone is generally the steroid used for maintenance therapy. Patients were divided into three groups based on the reported peak-PRA: 0%-30%, 31%-60% and > 60%. Under each peak-PRA category, patients were further divided into two groups: Those who underwent ESW before the hospital discharge (ESW group) and those who were discharged on steroid maintenance. The latter group was designated as chronic steroid maintenance (CSM) group. This was an intention-to-treat analysis using the maintenance immunosuppression regimen at the time of discharge from the initial transplant hospitalization as the basis for defining the groups. Changes in maintenance immunosuppression that occurred after initial discharge were not used to classify study subjects. We did not include patients who received live donor kidneys, multi-organ transplants, no induction, more than one induction, induction therapy with a different agent or maintenance other than CNI/MMF based regimen in the analysis.

Demographic variables for the different induction groups were collected. Graft was considered failed when one of the following occurred: need for maintenance dialysis, re-transplantation or patient death. Over all and death-censored graft as well as patient survivals were compared between ESW and CSM groups for each peak-PRA group after adjusting for pre-specified variables. We decided to use an adjusted model in the analysis due to substantial variations in the demographic features for ESW vs CSM in each peak-PRA category. The co-variates known to have adverse impact on the graft outcome and included in the model were donor related factors: age, gender, expanded criteria donor kidney, donation after cardiac death kidney, death from cerebrovascular accident; recipient related factors: age, African American race, diabetes mellitus, dialysis duration, number of HLA mismatches; and transplant related factors: cold ischemia time, induction type, delayed graft function (DGF, defined as the need for dialysis within the first week after transplantation), previous transplant, 12 mo acute rejection, and transplant year. Most of the patients were discharged on tacrolimus as the CNI agent; hence we did not include the type of CNI agent in the model. Since older KTRs could be more prone to the risks of enhanced immunosuppression, a further analysis was done comparing adjusted overall and death-censored graft failure risks as well as patient death risk between CSM and ESW groups in the subgroup of patient ≥ 60 years of age stratified by the peak-PRA class.

Comparisons among groups were made using 2-tailed t-test for continuous variables and chi square test for categorical variables. Values were expressed as mean ± SD, median with range or percentage. When there were missing data for different variables/risk factors in the registry, we assumed absence of the risk factor for the purpose of analysis. Less than 2% of the data were missing for different variables used in the analysis except for treated acute rejection where 20%-25% of data were missing. Adjusted (multivariate, after correcting for the confounding variables listed above) over all and death-censored graft as well as patient survivals were calculated and were compared between CSM vs ESW groups within each peak-PRA category using a Cox regression model. A further analysis comparing adjusted overall and death-censored graft failure as well as patient death risks in CSM vs ESW was performed in the subgroup of patients ≥ 60 years of age stratified by the peak-PRA class. Hazard ratio (HR and 95%CI) were calculated. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 14.

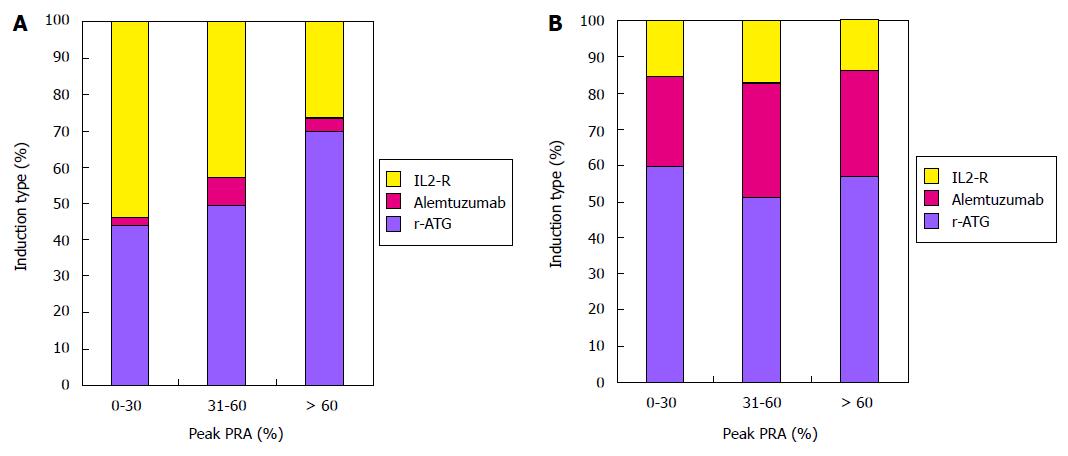

Median follow-up in months with range by peak-PRA category were as follows: 0%-30%, 36.1 (21.5 to 60.0); 31%-60%, 36.0 (20.4 to 60.7); > 60%, 35.1 (18.0 to 57.4). Trends in the utilization of different induction agents stratified by steroid use and peak-PRA class are shown in Figure 1. In CSM group, proportion of patients receiving r-ATG induction increased from low to high peak PRA groups. Alemtuzumab was predominantly used in ESW group.

A total of 42851 DDK recipients were included in the analysis. Among these patients, 9172 (21%) were in the ESW group and 33679 (79%) in CSM group. Distribution of the 42851 study patients by peak-PRA class was as follows: 0%-30%, n = 32617 (steroid = 25218, no steroid = 7399); 31%-60%, n = 4345 (steroid = 3495, no steroid = 850); > 60%, n = 5889 (steroid = 4966, no steroid = 923). There were substantial variations for steroid vs no steroid groups under each peak-PRA group as shown in Table 1. Of note, a consistently higher proportion of patients with previous transplants and DGF were discharged on steroid maintenance. There were more diabetics in the ESW groups likely reflective of the practice of avoiding steroids in patients with high blood sugar. Another observation is the trend in increasing dialysis duration and proportion of patients with prior transplants from the lowest to highest peak-PRA groups.

| Peak-PRA 0%-30% | Peak-PRA 31%-60% | Peak-PRA > 60% | ||||

| Steroid | No steroid | Steroid | No steroid | Steroid | No steroid | |

| (n = 25218) | (n = 7399) | (n = 3495) | (n = 850) | (n = 4966) | (n = 923) | |

| Donor factors | ||||||

| Age | 38 ± 17 | 39 ± 17b | 37 ± 17 | 38 ± 18 | 35 ± 15 | 35 ± 16 |

| Gender (M/F) % | 59/41 | 59/41 | 60/40 | 57/43 | 60/40 | 66/34b |

| Death from CVA (%) | 42 | 40a | 38 | 41a | 36 | 35a |

| ECD kidney (%) | 18 | 20d | 15 | 22d | 8 | 10 |

| DCD kidney (%) | 7.7 | 9.1d | 6.1 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 8.1 |

| Recipient factors | ||||||

| Age (yr) | 51 ± 13 | 53 ± 13d | 37 ± 17 | 38 ± 17 | 47 ± 13 | 49 ± 13 |

| Gender (M/F) % | 66/34 | 67/33 | 51/49 | 51/49 | 37/63 | 34/66 |

| African American | 30 | 26d | 28 | 28 | 33 | 31 |

| Diabetes | 33 | 36d | 29 | 34b | 25 | 28 |

| Pre-transplant dialysis (%) | 91 | 88d | 89 | 84d | 91 | 91 |

| Dialysis duration (mo) | 45 ± 34 | 44 ± 35a | 49 ± 42 | 47 ± 42 | 61 ± 51 | 59 ± 52 |

| Previous transplant (%) | 7.3 | 4.6d | 21.8 | 14.6d | 44.2 | 37.9d |

| HLA mismatches | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 3. 7 ± 1.9 | 3.5 ± 2.0 | 3.1 ± 2.0a | 3.1 ± 2.0 | 3.0 ± 2.0 |

| Transplant- related factors | ||||||

| Cold ischemia (h) | 18.1 ± 8.1 | 18.8 ± 8.0d | 18.3 ± 7.9 | 20.8 ± 10.2d | 18.4 ± 8.1 | 19.3 ± 8.2b |

| Delayed graft function (%) | 24.4 | 19.5d | 22.9 | 19.6a | 26 | 20.8b |

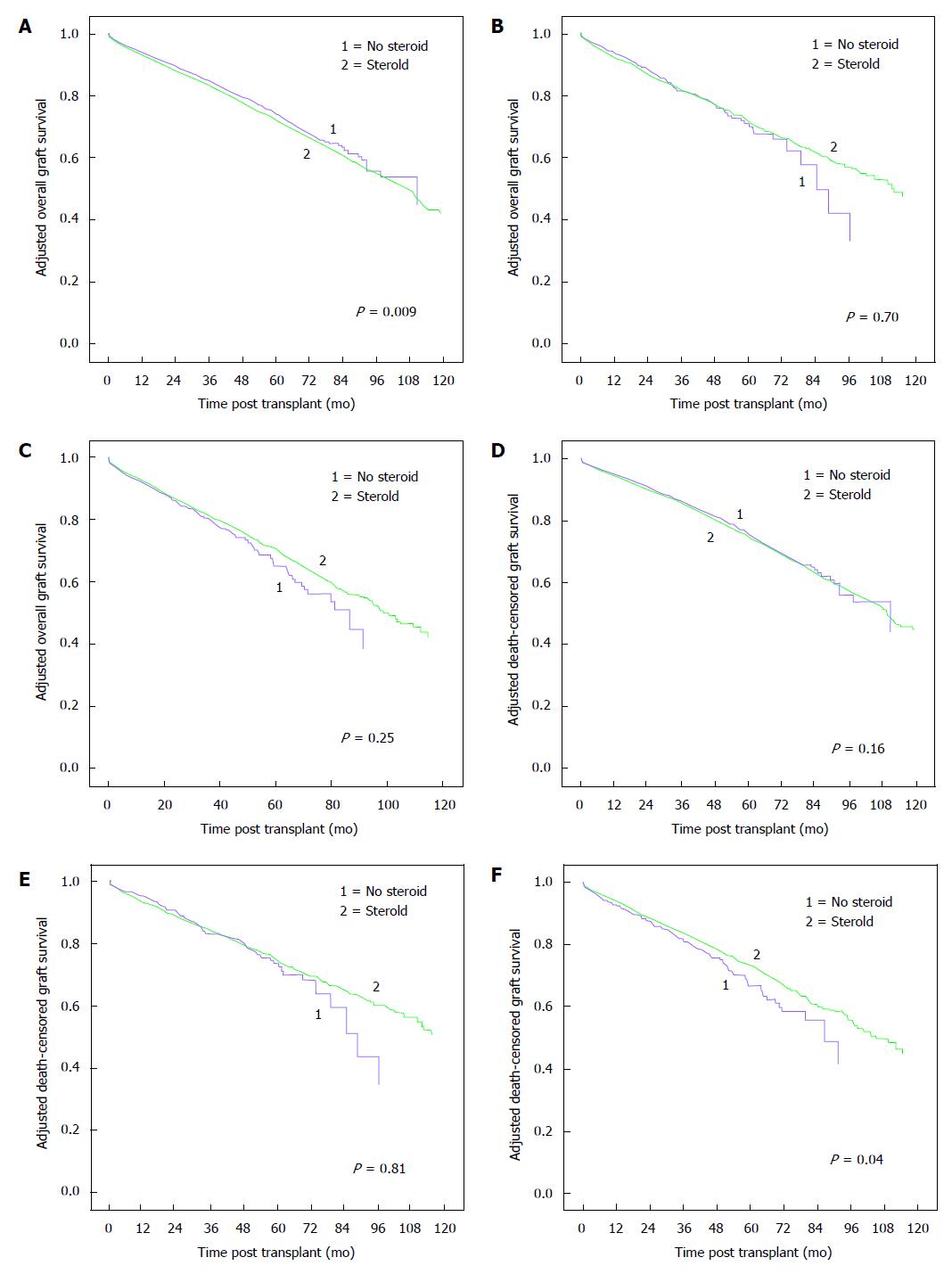

Adjusted overall and death-censored graft survivals for CSM vs ESW groups stratified by peak-PRA classes are shown in Figure 2. In patients with peak-PRA 0%-30%, there was higher adjusted overall graft failure risk (HR 1.11, 95%CI: 1.03-1.20, P = 0.009) but similar death-censored graft failure risk (HR 1.06, 95%CI: 0.98-1.14, P = 0.16) for CSM vs ESW groups. Adjusted over all (HR 1.04, 95%CI: 0.85-1.28, P = 0.70) and death-censored (HR 0.97, 95%CI: 0.78-1.21, P = 0.81) graft failure risks were similar for CSM vs ESW groups in the 31%-60% peak-PRA group. For patients in the > 60% peak-PRA group, adjusted overall graft failure risk was similar (HR 0.90, 95%CI: 0.76-1.08, P = 0.25) but death-censored graft failure risk was lower (HR 0.84, 95%CI: 0.71-0.99, P = 0.04) for CSM vs ESW groups.

A further analysis was performed comparing adjusted overall and death-censored graft survivals between ESW and CSM groups in patients ≥ 60 years of age stratified by peak-PRA class as shown in Table 2. CSM was associated with higher adjusted overall and death-censored graft failure risks in the 0%-30% peak-PRA group. There were no significant graft outcome differences between the groups for patients in the 31%-60% and > 60% peak-PRA groups.

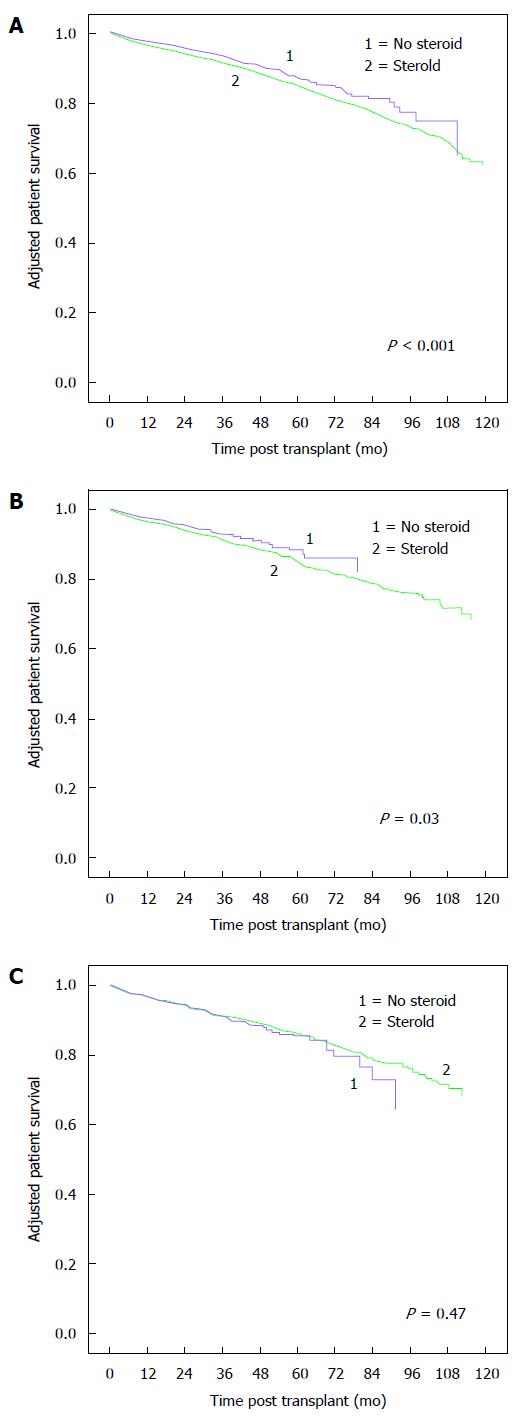

Adjusted patient survivals for the different peak-PRA groups are shown in Figure 3. Adjusted patient death risks were higher for CSM vs ESW groups in peak-PRA groups 0%-30% (HR 1.29, 95%CI: 1.16-1.43, P < 0.001) and 31%-60% (HR 1.39, 95%CI: 1.03-1.87, P = 0.03). There was no difference in adjusted patient death risk for ESW vs CSM in the > 60% peak-PRA group. In KTRs ≥ 60 years of age, adjusted patient death risk was higher for CSM vs ESW group in 0%-30% peak-PRA class. Adjusted patient death risks were similar between CSM and ESW groups for higher peak-PRA classes (Table 2).

Our study demonstrated an association between the addition of steroid to a CNI/MMF maintenance regimen and risk of patient death in DDK transplant recipients considered low immunological risk defined as peak-PRA 0%-30%. Increased overall but similar death-censored graft survival suggests an increased risk for death with functioning graft associated with steroid use in this group. Steroid use was associated with an improved death-censored graft survival without adversely affecting patient survival in high immune risk patients with peak-PRA > 60%. In the subgroup of patients ≥ 60 years of age, steroid use was associated with inferior graft and patient outcomes in low immune-risk patients and no significant benefits in high-immune risk patients. All study patients received perioperative induction therapy.

Several studies in the past have looked at the safety and efficacy of ESW in KTR[6-8]. Woodle et al[9] performed a prospective, randomized multicenter trial comparing early corticosteroid withdrawal vs long-term, low-dose corticosteroid therapy in KTR who received antibody induction followed by CNI/ MMF based immunosuppression therapy. Early steroid cessation was associated with slightly higher risk of steroid sensitive Banff 1A cellular rejection which did not translate into adverse long term graft survival and function. ESW was associated with reductions in the incidences of new onset diabetes after transplant, hypertriglyceridemia, and significant weight gain[9]. Risk factors for the development of acute rejection in patients who underwent ESW included repeat transplantation and lack of r-ATG use. There was a trend towards increased acute rejection in patients with PRA greater than 50%[13]. Rates of acute rejection, graft survival and patient survival were 40%, 88% and 96% respectively in a pilot study involving 25 high immune risk patients who underwent ESW and followed for 402 d[14]. Rates of acute rejection were lower in high immune risk patients who underwent steroid withdrawal if they received r-ATG induction. A recent analysis of the OPTN database involving large number of repeat KTR showed no added benefits of steroid maintenance in terms of patient or graft survival in the group that received perioperative induction with r-ATG[15]. A meta-analysis of 15 randomized control trials involving 3520 patients showed no significantly increased risk for acute rejection following very ESW if patients received perioperative induction followed by tacrolimus as part of maintenance therapy[16]. In fact, a recent study involving close to 42000 patients reported a highly significant association between maintenance steroid dose and death with functioning graft caused by cardiovascular disease or infection beyond the first year following DDK transplantation[17]. Neither tacrolimus nor mycophenolic acid use was associated with risk for death with functioning graft.

It makes intuitive sense that the higher immunologic risk KTR might benefit from enhanced immunosuppression with chronic steroid use. To our best knowledge, no previous studies specifically evaluated to find a threshold peak-PRA level beyond which the benefits of enhanced immunosuppression with CSM in terms of improved graft outcome begin to emerge. Our analysis did not reveal any clinically detectable graft and patient survival advantages in KTRs with peak PRA ≤ 60 who underwent perioperative induction therapy followed by CNI/MMF maintenance. An improved death-censored graft survival was associated with steroid maintenance in those with PRA > 60%. In the subgroup of older KTRs ≥ 60 years of age, steroid maintenance was not associated with survival benefits regardless of the level of sensitization.

One could speculate enhanced immunosuppression with risk for infectious complications as well as adverse metabolic and cardiovascular effects as possible reasons for the observed association between steroid maintenance and increased risk for death with functioning graft in low immune risk patients. Improved death censored graft survival associated with steroid use without adversely affecting patient survival in highly sensitized group suggests that favorable immunosuppressive effect of CSM in these patients is not fully offset by any adverse consequences of CSM.

In order to perform the current analysis, we utilized a cohort of patients from 2000-2008, an era before the concept of calculated panel reactive antibody (cPRA) which was introduced in 2009. The cPRA is based on the unacceptable antigens which if present in the donor would not be acceptable for the recipient. Depending on the frequency of the unacceptable antigens in the donor population, the cPRA is computed[18]. Unlike traditional PRA, cPRA provides a meaningful estimate of transplantability for most patients, as it would preclude offers from donors who could have a positive cross-match. Hence cPRA is described as a measure that provides both consistency and accountability[19]. cPRA as a concept introduced fairly recently may offer a better predictive survival as it takes into account the virtual cross-match. The contemporary cPRA is determined using extremely sensitive solid phase assays such as Luminex® that can detect very low levels of anti-HLA antibodies that may have questionable clinical relevance as compared to the poorly sensitive cell based assays used in the past to determine traditional PRA. One could speculate that PRA from previous era may reflect a higher degree of immunological risk. Our analysis of patient cohort from the traditional PRA era shows a seemingly beneficial effect of steroid maintenance only in younger patients with peak-PRA > 60%. This observation may be even more relevant to contemporary transplant recipients whose immunological risk is stratified by cPRA.

Our study has limitations. Retrospective analyses can only show associations but not causation. Despite using a multivariate model, confounding bias may still exist. Peak-PRA reflects the level of sensitization at a time point and does not give the actual degree of sensitization in the post-transplant period. Donor specific antibody (DSA) is increasingly available in current day practice which could be a more accurate determinant of the alloreactivity to specific donor and the risk of rejection. We did not have data on DSA in our study cohort. Changes in maintenance immunosuppression made after the initial hospital discharge were not captured. Hence patients who were withdrawn from steroids after hospital discharge, or if patients were initiated on steroids due to an event such as acute rejection episode at a later date would be misclassified. The impact of these misclassifications on the results likely is minimal since the non-differential nature of such influence tends to deflate results toward the null[20]. A recent registry analysis identified African American race, re-transplants, highly sensitized recipients, recipients with Medicaid, elevated HLA mismatches and older donor age as risk factors for new initiation of steroids in DDK recipients who were initially discharged on an ESW regimen[21]. There were differences in the patterns of induction therapy used in ESW vs CSM groups under each peak-PRA category. We attempted to minimize the impact of this by including type of induction therapy as a variable in the multivariate model. Therapeutic levels of CNI and doses of MMF were not available that could potentially influence graft outcomes. Possibility of type 1 error cannot be excluded. Despite these limitations, relatively large number of study patients from a national cohort adds to the validity of our findings.

In summary, our analysis showed that steroid can be safely withdrawn early and potentially could even be beneficial in sensitized DDK transplant recipients with a peak PRA ≤ 60% as well as elderly patients regardless of their degree of HLA sensitization provided these patients receive perioperative induction therapy followed by CNI (in particular tacrolimus)/MMF maintenance. On the other hand, steroid maintenance appears beneficial in the subgroup of highly sensitized younger patients. Randomized trials with sufficient size and follow up will be needed to further evaluate these clinically important findings.

Accepted in part for Oral presentation at the American Transplant Congress 2013, Seattle, WA and as a Poster at World Transplant Congress, San Francisco July 2014. This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 231-00-0115. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government.

Analysis of the beneficial effects of steroid maintenance in kidney transplant recipients (KTR) stratified by level of sensitization.

Beneficial effects of steroid maintenance were observed only in highly sensitized younger KTR with peak-panel reactive antibody > 60%.

In clinical transplantation.

The present study evaluated the probable threshold levels of sensitization at which there a benefit with maintenance of steroids in deceased-donor KTR. The study is very well written, the results are clearly presented and the discussion and limitations of the study adequately addressed.

P- Reviewer: Papagianni A, Zhang L S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9 Suppl 3:S1-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 1094] [Article Influence: 68.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vincenti F, Monaco A, Grinyo J, Kinkhabwala M, Roza A. Multicenter randomized prospective trial of steroid withdrawal in renal transplant recipients receiving basiliximab, cyclosporine microemulsion and mycophenolate mofetil. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:306-311. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Matas AJ, Kandaswamy R, Gillingham KJ, McHugh L, Ibrahim H, Kasiske B, Humar A. Prednisone-free maintenance immunosuppression-a 5-year experience. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2473-2478. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Rostaing L, Cantarovich D, Mourad G, Budde K, Rigotti P, Mariat C, Margreiter R, Capdevilla L, Lang P, Vialtel P. Corticosteroid-free immunosuppression with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and daclizumab induction in renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;79:807-814. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kumar MS, Heifets M, Moritz MJ, Saeed MI, Khan SM, Fyfe B, Sustento-Riodeca N, Daniel JN, Kumar A. Safety and efficacy of steroid withdrawal two days after kidney transplantation: analysis of results at three years. Transplantation. 2006;81:832-839. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Vincenti F, Schena FP, Paraskevas S, Hauser IA, Walker RG, Grinyo J. A randomized, multicenter study of steroid avoidance, early steroid withdrawal or standard steroid therapy in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:307-316. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Pascual J, Zamora J, Galeano C, Royuela A, Quereda C. Steroid avoidance or withdrawal for kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:CD005632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schiff J, Cole EH. Renal transplantation with early steroid withdrawal. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:243-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Woodle ES, First MR, Pirsch J, Shihab F, Gaber AO, Van Veldhuisen P. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial comparing early (7 day) corticosteroid cessation versus long-term, low-dose corticosteroid therapy. Ann Surg. 2008;248:564-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Knight SR, Morris PJ. Steroid avoidance or withdrawal after renal transplantation increases the risk of acute rejection but decreases cardiovascular risk. A meta-analysis. Transplantation. 2010;89:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rizzari MD, Suszynski TM, Gillingham KJ, Dunn TB, Ibrahim HN, Payne WD, Chinnakotla S, Finger EB, Sutherland DE, Kandaswamy R. Ten-year outcome after rapid discontinuation of prednisone in adult primary kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:494-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Luan FL, Steffick DE, Gadegbeku C, Norman SP, Wolfe R, Ojo AO. Graft and patient survival in kidney transplant recipients selected for de novo steroid-free maintenance immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:160-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Woodle ES, Alloway RR, Hanaway MJ, Buell JF, Thomas M, Roy-Chaudhury P, Trofe J. Early corticosteroid withdrawal under modern immunosuppression in renal transplantation: multivariate analysis of risk factors for acute rejection. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:798-799. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Alloway RR, Hanaway MJ, Trofe J, Boardman R, Rogers CC, Hanaway MJ, Buell JF, Munda R, Alexander JW, Thomas MJ. A prospective, pilot study of early corticosteroid cessation in high-immunologic-risk patients: the Cincinnati experience. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:802-803. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sureshkumar KK, Hussain SM, Nashar K, Marcus RJ. Steroid maintenance in repeat kidney transplantation: influence of induction agents on outcomes. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2014;25:741-749. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Zhang X, Huang H, Han S, Fu S, Wang L. Is it safe to withdraw steroids within seven days of renal transplantation? Clin Transplant. 2013;27:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Opelz G, Döhler B. Association between steroid dosage and death with a functioning graft after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2096-2105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nikaein A, Cherikh W, Nelson K, Baker T, Leffell S, Bow L, Crowe D, Connick K, Head MA, Kamoun M. Organ procurement and transplantation network/united network for organ sharing histocompatibility committee collaborative study to evaluate prediction of crossmatch results in highly sensitized patients. Transplantation. 2009;87:557-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cecka JM. Calculated PRA (CPRA): the new measure of sensitization for transplant candidates. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:26-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Copeland KT, Checkoway H, McMichael AJ, Holbrook RH. Bias due to misclassification in the estimation of relative risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;105:488-495. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Schold JD, Santos A, Rehman S, Magliocca J, Meier-Kriesche HU. The success of continued steroid avoidance after kidney transplantation in the US. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2768-2776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |