Published online Jun 24, 2014. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v4.i2.148

Revised: May 6, 2014

Accepted: June 10, 2014

Published online: June 24, 2014

Processing time: 131 Days and 6.2 Hours

We are reporting the first documented case of an abdominal desmoid tumor presenting primarily after liver transplantation. This tumor, well described in the literature as occurring both in conjunction with familial adenomatous polyposis as well as in the post-surgical patient, has never been noted after solid organ transplantation and was therefore not included in our differential upon presentation. Definitive diagnosis required the patient to undergo surgical excision and immunochemical staining of the mass for confirmation. A review of the literature showed no primary tumors after transplantation. In a population of patients who received a small bowel transplant after they developed short gut post radical resection of aggressive fibromatosis, only rare recurrences were seen. No connection of tumor development with immunosuppression or need to decrease immunosuppressant treatment has been demonstrated in these patients. Our case and the literature show the risk of this tumor presenting in the post-transplantation patient and the need for a high index of suspicion in patients who present with a complex mass after transplantation to prevent progression of the disease beyond a resectable lesion. Results of a thorough search of the literature are detailed and the medical and surgical management of both resectable and unresectable lesions is reviewed.

Core tip: Desmoid tumor is a soft tissue tumor seen primarily after surgical resection. A high index of suspicion is necessary as delayed diagnosis can cause significant morbidity with resection. This case presents the first observed desmoid after liver transplantation as well as a literature search detailing the observed desmoid presentations in the context of immunosuppression.

- Citation: Fleetwood VA, Zielsdorf S, Eswaran S, Jakate S, Chan EY. Intra-abdominal desmoid tumor after liver transplantation: A case report. World J Transplant 2014; 4(2): 148-152

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v4/i2/148.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v4.i2.148

We present the first documented case of desmoid tumor appearing after solid organ transplantation. Desmoid tumors are a rare malignancy characterized by benign histology and aggressive local recurrence. Incidence and recurrence of desmoids in patients who have undergone transplantation and effects of immunosuppression on desmoid development have not yet been studied.

A 60-year-old male presented to our clinic with a three day history of right upper quadrant pain. He noted two months of fatigue and a recent history of diarrhea, resolved at admission. He denied nausea, vomiting, fevers, chills, or weight loss. Medical history was notable Hepatitis C cirrhosis status post orthotopic liver transplant approximately six months prior, as well as type II diabetes mellitus. Postoperatively, he received basiliximab on the day of transplant and on postoperative day 4 for induction along with a methylprednisolone taper in the days immediately post transplantation. He was maintained on cyclosporine and had previously shown no signs of graft rejection with historically appropriate levels of immunosuppressive therapy. He denied alcohol or drug abuse.

Physical exam was remarkable for tenderness to palpation over the right upper quadrant with a new marked right upper quadrant mass. Laboratory measurements revealed a white blood cell count of 4.32 × 109/L (reference range 1.5-10.5 × 109/L) with a normal differential, hemoglobin of 11.1 g/dL (reference range 13.5-17.5 g/dL), and creatinine of 1.29 mg/dL (reference range 0.75-1.2 mg/dL). Alkaline phosphatase was elevated at 281 mmol/L (reference range 30-125 mmol/L) and the transaminases and total bilirubin were within normal limits. Cyclosporine levels were within therapeutic ranges (100-150 ng/mL). He had received a colonoscopy at an outside institution two years prior significant only for benign polyps. Alfa-fetoprotein measurement was within normal limits (< 10 ng/mL). Computed tomography imaging showed a 13 cm multi-loculated heterogeneous fluid collection with hyperdense and hypodense components inferior to right hepatic tip with multiple cystic locules (Figure 1). The final radiologic report was read as “large complex multiloculated subhepatic peritoneal collection(s), likely multiloculated hematoma(s) as well as adjacent loculated hemoperitoneum. The adjacent mesentery now demonstrates amorphous enhancement and therefore superimposed infection/phlegmon cannot be excluded. These collection(s) are essentially new since the prior study (previously mild hemoperitoneum was present in the subhepatic region and both paracolic gutters).

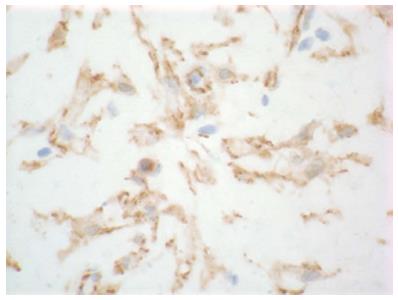

Based on the concern for infected hematoma, the patient was sent for placement of an interventional radiology drain into loculated fluid collection. Fluid pathology and cultures were nondiagnostic. The drain was placed under imaging guidance but was clearly unable to access loculated areas due to solid components interfering with catheter passage. As his symptoms were persistent and mass was well visualized with computed tomography, no further imaging appeared warranted; he was taken to the operating room, where exploratory laparotomy was performed. Intra-operatively the infrahepatic mass was noted to be white, inflamed, and fibrotic. Ten centimeters of small bowel and the mesentery were noted to be inseparably adhered to mass and inflamed, and they were resected en bloc with the mass. Grossly negative margins at abdominal wall and the involved small bowel were achieved but microscopic positivity was confirmed by frozen section in the posterior portion of the mass adjacent to the retroperitoneum. Final pathology returned with a low cellularity tumor with myofibroblasts in disarray in a myxoid matrix, beta-catenin stain positive (Figure 2), consistent with desmoid fibromatosis.

Our patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged home at prior functional status within ten days. Repeat imaging has been negative for signs of recurrence (Figure 3) in the 23 mo in which he has followed up since resection. He has been started on treatment for chronic hepatitis C with sobosfuvir and simeprevir therapy.

Desmoid tumors are rare tumors which fall into two types: sporadic and those associated with familial adenomatous polyposis. The incidence of desmoid is less than three percent of soft tissue sarcomas and about 0.03% of all malignancies[1]. They appear between 15 and 60 years with a peak age of appearance at 30 years[2]. Both types are characterized by monoclonal, fibroblastic proliferation with 80% rate of positive nuclear and cytoplasmic staining for beta-catenin[3]. They are histologically benign and do not metastasize but are frequently locally invasive and highly recurrent. Only 5% of sporadic desmoid tumors, in contrast with 80% of FAP-associated desmoids, occur intra-abdominally; other locations include extremities and trunk[1]. Both sporadic and FAP-associated desmoids have been well described in the surgical literature as recurring both within the surgical field and intra-compartmentally outside the surgical field. Differential diagnosis encompasses both fibroblastic sarcomas and other reactive fibroblastic process, but these can be distinguished from desmoids as the latter tend to occur with a diagnosis of FAP, nuclear staining for beta-catenin - present in roughly 80% of cases - and screening for mutations of beta-catenin gene, found in approximately 85% of sporadic cases[3]. Factors which prognosticate recurrence have been suggested to be sex[2] and mutations of the beta-catenin gene, the latter of which were found to be associated with significantly higher rates of local recurrence[4].

Treatment for these tumors includes a wide variety of approaches. As these tumors have no metastatic potential, treatment is usually dictated by rapidity of growth and functional considerations such as pain or local obstruction. Surgical management has historically been the first-line treatment of desmoids[5]. Negative margins are generally the goal of surgical intervention; however, for intra-abdominal type especially, morbidity associated with surgery may prevent definitive excision with negative margins. Results have been mixed on whether negative margins were predictive of lower recurrence rate[6]. In a case series including 56 patients with either intra- or extra-abdominal primary disease, microscopically positive margins were associated with an almost fourfold increase in local recurrence compared to microscopically negative margins, but no difference in overall survival was observed[7]. A review of multiple studies addressing margin status concluded that no definitive conclusion could be reached based on available evidence and that negative margins should be strove for if they did not compromise functional status[8].

Adjunctive radiotherapy in patients with positive margins has been explored in depth and shown to result in decreased relapse rates but significant complications, including tissue fibrosis[9]. Radiotherapy has not been strongly evaluated in patients with negative surgical margins, as many patients with negative margins elect not to undergo radiation therapy. In a comparative review of 22 cases, radiation therapy alone demonstrated a local control rate of 78% as opposed to 61% with surgery alone[10]. However, multiple complications were noted and, given the accompanying tissue damage and peak occurrence of desmoids in young patients, it is generally recommended to use radiation therapy only as an adjunct to surgery or for unresectable disease[11].

For unresectable disease, a wide variety of medical treatments have been used, although few have been systematically evaluated. A systematic review of the literature addressed the different strategies noted below[12]. As most desmoid tumors express nuclear estrogen receptor-B, tamoxifen and other anti-estrogens have been used with some anecdotal reports of response; however, this has not been evaluated in a larger series. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have also been tested and have demonstrated activity against tumors with partial or complete response. In cases of rapidly growing or symptomatic tumor, cytotoxic agents such as methotrexate and vinblastine have been studied; however, these were evaluated largely in the pediatric population and are associated with high, although tolerable, levels of toxicity[6]. Imatinib is another agent which is currently under study and has shown promise in multiple low-powered studies[13,14] but has not yet been licensed for this indication[6].

No incidences of primary desmoid tumor development have yet been documented in patients who have undergone transplantation of liver or other solid organs. Recurrence of pre-transplant desmoids in patients known to be on immunosuppression, in this case for intestinal transplant, is only addressed in one series. Fourteen patients with desmoid tumors underwent intestinal transplantation, of which three recurred; time interval to recurrence was 15, 17 and 69 mo. Of these patients, eleven were maintained on immunosuppression[15]. In a European study of both intra- and extra-abdominal fibromatosis, recurrence was seen at between 0 and 204 mo in 37 patients with a mean time of 14 to 17 mo[7]. Although these studies show similar time to recurrence, the power of the study addressing the immunosuppressed patient is so low that it is difficult to draw conclusions on the impact of immunosuppressive therapy on recurrence.

Our patient presented with a sporadic primary tumor. We were able to achieve a grossly negative resection but pathology revealed microscopic disease at the margins; he received no adjunctive therapy but has not recurred at 23 mo, suggesting that his immunosuppression has not caused rapid growth or recurrence.

In conclusion, desmoid tumors are a rare disease for which the primary standard of care differs between surgical excision or watchful waiting, depending on extent of involvement of surrounding structures and postoperative morbidity. We presented a hitherto undocumented case of sporadic desmoid tumor after liver transplantation. The patient has no personal or family history of familial adenomatous polyposis. The primary manifestation was treated with surgical excision. No incidences of primary desmoid tumor development have yet been documented in patients who have undergone transplantation of liver or other solid organs. Influence of immunosuppression on the development of desmoids is unknown; on recurrence, poorly studied. Further study would be helpful to elaborate the effect of immunosuppression on development of desmoids and the rates of recurrence after solid organ transplant.

A 60-year-old male with a history of liver transplantation presented with right upper quadrant pain.

Clinical findings were a palpable tender mass in right upper quadrant.

Differential diagnosis includes abscess, malignancy, and recurrent hepatitis.

Alkaline phosphatase 281 mmol/L, hemoglobin 11.1 g/dL, and creatinine of 1.29 mg/dL with otherwise normal complete metabolic panel and blood counts.

CT showed multiloculated, heterogeneous fluid collection with varying densities and cystic components inferior to and distinct from right hepatic tip; scattered periaortic lymph nodes were seen.

Pathology showed a low cellularity tumor with myofibroblasts in disarray in a myxoid matrix with positive beta-catenin staining.

The patient was treated with surgical resection; no adjunctive radiotherapy or chemotherapy was used.

This is the first case of desmoid tumor occurring primarily after organ transplantation; one previous case series addressing viability of small bowel transplantation after resection of desmoid tumor addressed recurrence of fibromatosis on immunosuppression but was insufficiently powered to reach a conclusion.

Nuclear beta catenin is a protein which regulates cell-cell adhesion and gene transcription encoded by the CTNNB1 gene; positive staining has been noted with desmoid tumors as well as with colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and lung cancer.

This case reports the first noted desmoid tumor occurring after solid organ transplantation and presents methods of treatment for both resectable and unresectable lesions as well as describing the literature available on desmoid tumors in immunosuppressed patients.

The manuscript entitled, “Intra-abdominal desmoid tumor after liver transplantation: a case report” by Fleetwood et al, reported a case of intra-abdominal desmoid tumor developing in a post liver transplant recipient. This is the first case presentation of intraabdominal desmoid tumor after liver transplantation, and worth for publication.

P- Reviewers: Ozden I, Sugawara Y S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Shields CJ, Winter DC, Kirwan WO, Redmond HP. Desmoid tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:701-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mankin H, Hornicek F, Springfield , D . Extra-abdominal desmoid tumors: A report of 234 cases. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:380-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Carlson JW, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin in the differential diagnosis of spindle cell lesions: analysis of a series and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2007;51:509-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dômont J, Salas S, Lacroix L, Brouste V, Saulnier P, Terrier P, Ranchère D, Neuville A, Leroux A, Guillou L. High frequency of beta-catenin heterozygous mutations in extra-abdominal fibromatosis: a potential molecular tool for disease management. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1032-1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shinagare AB, Ramaiya NH, Jagannathan JP, Krajewski KM, Giardino AA, Butrynski JE, Raut CP. A to Z of desmoid tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:W1008-W1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kasper B, Ströbel P, Hohenberger P. Desmoid tumors: clinical features and treatment options for advanced disease. Oncologist. 2011;16:682-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stoeckle E, Coindre JM, Longy M, Binh MB, Kantor G, Kind M, de Lara CT, Avril A, Bonichon F, Bui BN. A critical analysis of treatment strategies in desmoid tumours: a review of a series of 106 cases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Melis M, Zager JS, Sondak VK. Multimodality management of desmoid tumors: how important is a negative surgical margin? J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:594-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jelinek JA, Stelzer KJ, Conrad E, Bruckner J, Kliot M, Koh W, Laramore GE. The efficacy of radiotherapy as postoperative treatment for desmoid tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:121-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nuyttens JJ, Rust PF, Thomas CR, Turrisi AT. Surgery versus radiation therapy for patients with aggressive fibromatosis or desmoid tumors: A comparative review of 22 articles. Cancer. 2000;88:1517-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Practice Guidelines in Oncology – Guidelines for Treatment of Sarcoma. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#sarcoma. Web. 09/13/2013. |

| 12. | Janinis J, Patriki M, Vini L, Aravantinos G, Whelan JS. The pharmacological treatment of aggressive fibromatosis: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:181-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Heinrich MC, McArthur GA, Demetri GD, Joensuu H, Bono P, Herrmann R, Hirte H, Cresta S, Koslin DB, Corless CL. Clinical and molecular studies of the effect of imatinib on advanced aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumor). J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1195-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Penel N, Le Cesne A, Bui BN, Perol D, Brain EG, Ray-Coquard I, Guillemet C, Chevreau C, Cupissol D, Chabaud S. Imatinib for progressive and recurrent aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumors): an FNCLCC/French Sarcoma Group phase II trial with a long-term follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:452-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moon JI, Selvaggi G, Nishida S, Levi DM, Kato T, Ruiz P, Bejarano P, Madariaga JR, Tzakis AG. Intestinal transplantation for the treatment of neoplastic disease. J Surg Oncol. 2005;92:284-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |