Published online Sep 18, 2025. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v15.i3.102150

Revised: March 16, 2025

Accepted: April 1, 2025

Published online: September 18, 2025

Processing time: 190 Days and 11.5 Hours

Traditional limitations of cold static storage (CSS) on ice at 4 °C during lung transplantation have necessitated limiting cold ischemic time (CIT) to 4-6 hours. Ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) can extend this preservation time through the suspension of CIT and normothermic perfusion. As we continue to further expand the donor pool in all aspects of lung transplantation, teams are frequently tra

To determine the effect of CSS or EVLP on donors with extended travel distance [> 750 nautical miles (NM)] to recipient.

Lung transplants, whose donor traveled greater than 750 NM, were identified from the United Network for Organ Sharing Database. Recipients were stratified into either: CSS or EVLP, based on preservation method. Groups were assessed with comparative statistics and survival was assessed by Kaplan-Meier methods. A 3:1 propensity match was then created, and same analysis was repeated.

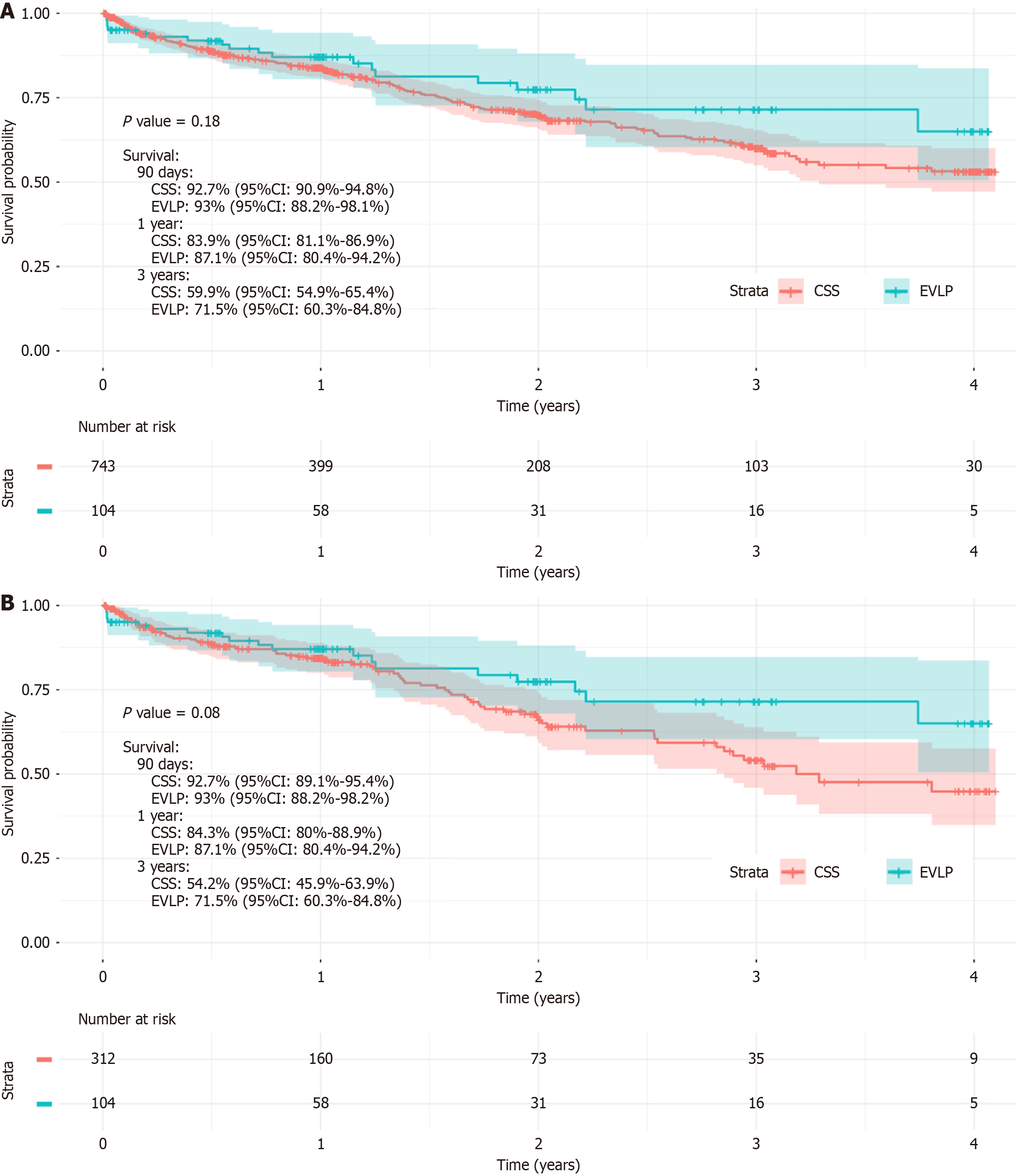

Prior to matching, those in the EVLP group had significantly increased post-operative morbidity to include dialysis, ventilator use, acute rejection, and treated rejection in the first year (P < 0.05 for all). However, there were no significant differences in midterm survival (P = 0.18). Following matching, those in the EVLP group again had significantly increased post-operative morbidity to include dialysis, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use, ventilator use, and treated rejection in the first year (P < 0.05 for all). As before, there were no significant differences in midterm survival following matching (P = 0.08).

While there was no significant difference in survival, EVLP patients had increased peri-operative morbidity. With the advent of changes in CSS with 10 °C storage further analysis is necessary to evaluate the best methods for utilizing organs from increased distances.

Core Tip: This study investigates the effectiveness of cold static storage (CSS) vs ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) for donor lungs transported over 750 nautical miles. Midterm survival outcomes were similar but recipients in the EVLP group experienced significantly higher perioperative morbidity, including post-operative dialysis and ventilator use. If ischemic times remain less than 8 hours, CSS remains likely a viable option for extended travel, especially in resource-limited settings. This research provides important insights for transplant centers seeking to optimize organ preservation strategies for long-distance donor retrieval.

- Citation: Reynolds M, Walsh MG, Cui EY, Satija D, Gouchoe DA, Henn MC, Choi K, Mokadam NA, Ganapathi AM, Whitson BA. Extended travel for donor organs: Is cold static storage still relevant. World J Transplant 2025; 15(3): 102150

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v15/i3/102150.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v15.i3.102150

Traditional limitations of cold static storage (CSS) on ice at 4 °C during lung transplantation have necessitated that a cold ischemic time (CIT) of around 4-6 hours allows for ideal graft function in the post-operative period[1,2]. Ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) can extend this preservation time through the suspension of CIT and normothermic perfusion[3]. However, despite increasing the donor pool, EVLP use can still be an overwhelming cost to smaller transplant centers[4]. As we continue to further expand the donor pool in all aspects of lung transplantation, teams are frequently traveling further distances to procure organs. In these cases, EVLP has been shown to be an effective way of preserving organs[3]. However, in this era dominated by machine perfusion, is CSS still a relevant option in extended travel of donor organs? Here we sought to determine the outcomes of preservation (EVLP vs CSS) in transplants when the donor to recipient hospital is greater than 750 nautical miles (NM).

The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database was queried to identify primary, adult lung transplants (age ≥ 18 years) with over 750 NM between donor and recipient hospitals from February 28, 2018 to March 30, 2023. Recipients were stratified into CSS or EVLP groups based on the preservation technique utilized.

Recipient baseline characteristics included age, sex, race, diabetes status, smoking history, lung allocation score (LAS), pulmonary function parameters, primary diagnosis (e.g., cystic fibrosis, obstructive lung disease, pulmonary vascular disease, restrictive lung disease), pre-transplant hospitalization status, waitlist duration, and mechanical ventilation requirement prior to transplant. Donor baseline characteristics included age, sex, smoking history, cause of death, PaO2/FiO2 (PF) ratio, history of hypertension or diabetes, and donation after circulatory death (DCD) status. Transplant-related factors such as distance traveled (NM), cold ischemia time (CIT), and ischemic time stratified by preservation strategy (CSS vs EVLP) were analyzed to assess their impact on outcomes.

A 3:1 propensity score matching analysis was performed using a nearest-neighbor greedy matching algorithm with a caliper width of 0.20 to balance recipient and donor characteristics across CSS and EVLP cohorts (Supplementary Figure 1). The recipient variables included in the propensity matching model were: (1) Age; (2) Sex; (3) Race; (4) LAS; (5) Pre-transplant hospitalization; (6) Pre-operative dialysis; (7) Diagnosis (restrictive vs obstructive lung disease); (8) Waitlist duration; and (9) Mechanical ventilation status. The donor variables included were: (1) Age; (2) Sex; (3) PF ratio; (4) Cause of death; and (5) DCD status.

Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were used to assess post-match balance, with SMD < 0.10 indicating well-balanced groups.

Continuous variables were assessed for normality using Shapiro-Wilk tests and visual inspection of Q-Q plots. Parametric data were reported as mean ± SD and compared using t-tests, while non-parametric data were reported as median [interquartile range (IQR)] and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were reported as counts and percentages and analyzed using χ² or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate.

Survival was assessed using Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank tests for both unmatched and propensity-matched cohorts. Survival curves were generated to compare mid-term survival outcomes between CSS and EVLP groups. Additionally, a Cox proportional hazards regression model was performed to assess independent predictors of survival, with adjustment for cold ischemia time, donor age, recipient age, recipient LAS, and DCD status. The proportional hazards assumption was verified using Schoenfeld residuals.

All analyses were performed using R version 3.6.2 (Vienna, Austria), and a two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 897 lung transplant recipients who received allografts from donors traveling > 750 NM were identified. Of these, 792 were in the CSS group and 105 in the EVLP group (Table 1).

| Variable | Overall (n = 897) | Cold static storage (n = 792) | Ex vivo lung perfusion (n = 105) | P value |

| Age | 64 (57, 68) | 64 (57, 68) | 63 (56, 68) | 0.365 |

| Male sex | 551 (61.4) | 490 (61.9) | 61 (58.1) | 0.522 |

| Race | 0.816 | |||

| White | 659 (73.5) | 582 (73.5) | 77 (73.3) | |

| Black | 89 (9.9) | 77 (9.7) | 12 (11.4) | |

| Other | 149 (16.6) | 133 (16.8) | 16 (15.2) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.6 (23.3, 29.4) | 26.7 (23.3, 29.4) | 26.4 (23.7, 29.3) | 0.67 |

| Diabetes | 150 (16.8) | 128 (16.3) | 22 (21) | 0.286 |

| Former smoker | 509 (56.7) | 444 (56.1) | 65 (61.9) | 0.404 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/minute/1.73 m2) | 91 (74.6, 119.3) | 90.3 (74.4, 117.8) | 97.2 (76.7, 125.3) | 0.286 |

| Mean pulmonary artery pressure (mm Hg) | 25 (20, 30.5) | 25 (20, 30) | 24 (21, 32) | 0.477 |

| Diagnosis | 0.755 | |||

| Cystic fibrosis/immunodeficiency | 24 (2.7) | 21 (2.7) | 3 (2.9) | |

| Obstructive lung disease | 207 (23.1) | 179 (22.6) | 28 (26.7) | |

| Pulmonary vascular disease | 36 (4) | 31 (3.9) | 5 (4.8) | |

| Restrictive lung disease | 630 (70.2) | 561 (70.8) | 69 (65.7) | |

| Lung allocation score | 41.2 (35.7, 55.2) | 41.3 (35.8, 55.9) | 40.5 (35.5, 53.7) | 0.434 |

| Hospitalized prior to transplant | 0.8 | |||

| Not hospitalized | 643 (75.5) | 561 (75.1) | 82 (78.1) | |

| Hospitalized | 82 (9.6) | 73 (9.8) | 9 (8.6) | |

| In intensive care unit | 127 (14.9) | 113 (15.1) | 14 (13.3) | |

| Pre-operative ventilator | 47 (5.2) | 44 (5.6) | 3 (2.9) | 0.351 |

| Pre-operative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 58 (6.5) | 54 (6.8) | 4 (3.8) | 0.334 |

| Days on wait list | 34 (12, 117) | 33 (12, 116) | 42 (14, 122) | 0.482 |

Recipient demographics and comorbidities were similar between groups (Table 1). Median recipient age was 64 years (IQR: 57–68) in CSS vs 63 years (IQR: 56–68) in EVLP (P = 0.365). Sex distribution did not significantly differ (male: 61.9% in CSS vs 58.1% in EVLP, P = 0.522).

Primary diagnosis was comparable, with restrictive lung disease as the most common indication (CSS: 70.8% vs EVLP: 65.7%, P = 0.755). No significant differences were observed in LAS (41.3 vs 40.5, P = 0.434), former smoking history (56.1% vs 61.9%, P = 0.404), or preoperative dialysis requirement (P > 0.05 for all).

Donor characteristics were also well balanced between groups (Table 2). Median donor age was 35 years (IQR: 24–47) in CSS vs 38 years (IQR: 25–51) in EVLP (P = 0.082). Donor sex, history of smoking (9.6% vs 11.5%, P = 0.648), diabetes (10.7% vs 10.6%, P = 0.999), and hypertension (26.8% vs 27.6%, P = 0.954) were not significantly different. However, PF ratio was significantly lower in EVLP donors (408.5 vs 454, P < 0.001), indicating increased use of EVLP for donors with borderline oxygenation. Additionally, EVLP lungs were significantly more likely to be from DCD donors (30.5% vs 7.8%, P < 0.001).

| Variable | Overall (n = 897) | Cold static storage (n = 792) | Ex vivo lung perfusion (n = 105) | P value |

| Age | 35 (25, 48) | 35 (24, 47) | 38 (25, 51) | 0.082 |

| Male sex | 562 (62.7) | 497 (62.8) | 65 (61.9) | 0.951 |

| Coronary artery disease | 57 (6.5) | 52 (6.8) | 5 (4.8) | 0.585 |

| Smoking history | 86 (9.8) | 74 (9.6) | 12 (11.5) | 0.648 |

| Recent cocaine use | 195 (22.1) | 172 (22.1) | 23 (22.1) | 0.5 |

| Diabetes | 95 (10.7) | 84 (10.7) | 11 (10.6) | 0.999 |

| Hypertension | 240 (26.9) | 211 (26.8) | 29 (27.6) | 0.954 |

| Alcohol abuse | 180 (20.7) | 162 (21.2) | 18 (17.3) | 0.429 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26 (23, 30) | 25.9 (23, 29.9) | 27.1 (23, 32.7) | 0.15 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 449 (396.9, 506) | 454 (400, 507.4) | 408.5 (361, 487.1) | < 0.001 |

| Donor cause of death | 0.568 | |||

| Neuro (seizure/cerebral vascular accident) | 259 (28.9) | 231 (29.2) | 28 (26.9) | |

| Drug overdose | 136 (15.2) | 126 (15.9) | 10 (9.6) | |

| Asphyxiation | 56 (6.2) | 48 (6.1) | 8 (7.7) | |

| Cardiovascular | 71 (7.9) | 61 (7.7) | 10 (9.6) | |

| Trauma (gun shot wound/stab/blunt) | 331 (36.9) | 290 (36.6) | 41 (39.4) | |

| Drowning | 4 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (1) | |

| Other | 39 (4.4) | 33 (4.2) | 6 (5.8) | |

| Donation after circulatory death | 94 (10.5) | 62 (7.8) | 32 (30.5) | < 0.001 |

CIT was significantly longer in the EVLP group [13.5 hours (IQR: 10.8–16.2) vs 7.1 hours (IQR: 6.1–8.2), P < 0.001], reflecting the additional time required for perfusion and evaluation (Table 3). However, distance traveled did not differ (900 NM vs 892 NM, P = 0.96), suggesting preservation technique rather than transport distance contributed to ischemic time differences. Recipients in the EVLP group had significantly higher post-transplant morbidity in terms of dialysis requirement (15.4% vs 8.8%, P = 0.049), prolonged ventilator use (≥ 5 days) (35.9% vs 24.8%, P = 0.011), treated rejection within the first year (30.9% vs 13.9%, P = 0.001), acute rejection requiring hospitalization (10.5% vs 5.1%, P = 0.014). Despite these differences, there was no significant difference in in-hospital mortality (8.7% vs 7.0%, P = 0.668) or length of stay (22 days vs 20 days, P = 0.553).

| Variable | Overall (n = 897) | Cold static storage (n = 792) | Ex vivo lung perfusion (n = 105) | P value |

| Center volume | 30 (12, 56) | 30 (12, 56) | 32 (14, 56) | 0.526 |

| Center volume yearly | 2 (0.8, 3.7) | 2 (0.8, 3.7) | 2.1 (0.9, 3.7) | 0.526 |

| Perfused by | ||||

| Organ perfusion organization | 2 (1.9) | |||

| Transplant program | 61 (58.7) | |||

| External perfusion center | 41 (39.4) | |||

| Perfusion time | 296 (218, 496) | |||

| Warm ischemic time | 24 (19.3, 28) | 24 (19, 26.8) | 25.5 (20, 30.3) | 0.113 |

| Type of lung transplant | 0.001 | |||

| Bilateral | 653 (72.8) | 561 (70.8) | 92 (87.6) | |

| Right single | 100 (11.1) | 96 (12.1) | 4 (3.8) | |

| Left single | 144 (16.1) | 135 (17) | 9 (8.6) | |

| Distance traveled (nautical miles) | 898 (824, 1006) | 900 (824, 1006) | 892 (826, 1058) | 0.96 |

| Ischemic time (hours) | 7.3 (6.2, 8.8) | 7.1 (6.1, 8.2) | 13.5 (10.8, 16.2) | < 0.001 |

| Length of stay (days) | 20 (13, 38) | 20 (13, 37) | 22 (14, 48.5) | 0.553 |

| In-hospital mortality | 59 (7.2) | 50 (7) | 9 (8.7) | 0.668 |

| Postop dialysis | 81 (9.6) | 65 (8.8) | 16 (15.4) | 0.049 |

| Postop stroke | 34 (4) | 30 (4) | 4 (3.8) | 0.999 |

| Airway dehiscence | 16 (1.9) | 16 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 0.254 |

| Post-operative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 97 (11.5) | 79 (10.7) | 18 (17.3) | 0.068 |

| Post-operative ventilator | 0.011 | |||

| None | 7 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) | 2 (1.9) | |

| < 2 days | 445 (53.1) | 405 (55.1) | 40 (38.8) | |

| 2-5 days | 167 (19.9) | 143 (19.5) | 24 (23.3) | |

| 5+ days | 219 (26.1) | 182 (24.8) | 37 (35.9) | |

| Primary graft dysfunction grade 3 | 123 (13.7) | 108 (13.6) | 15 (14.3) | 0.975 |

| Acute rejection (hospitalization) | 0.014 | |||

| Yes and treated with immunosuppressant | 49 (5.8) | 38 (5.1) | 11 (10.5) | |

| Yes and not treated with Immunosuppressant | 5 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) | 2 (1.9) | |

| No | 792 (93.6) | 700 (94.5) | 92 (87.6) | |

| Treated rejection (1st year) | 84 (16.2) | 63 (13.9) | 21 (30.9) | 0.001 |

| Cause of death | 0.827 | |||

| Graft failure | 35 (17.9) | 32 (18.3) | 3 (15) | |

| Malignancy | 4 (2.1) | 4 (2.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Cardio/cerebrovascular | 29 (14.9) | 25 (14.3) | 4 (20) | |

| Pulmonary | 33 (16.9) | 29 (16.6) | 4 (20) | |

| Infection | 58 (29.7) | 51 (29.1) | 7 (35) | |

| Other | 36 (18.5) | 34 (19.4) | 2 (10) | |

| Year of transplant | ||||

| 2018 | 96 (10.7) | 83 (10.5) | 13 (12.4) | |

| 2019 | 142 (15.8) | 122 (15.4) | 20 (19) | |

| 2020 | 170 (19) | 153 (19.3) | 17 (16.2) | |

| 2021 | 209 (23.3) | 180 (22.7) | 29 (27.6) | |

| 2022 | 220 (24.5) | 197 (24.9) | 23 (21.9) | |

| 2023 | 60 (6.7) | 57 (7.2) | 3 (2.9) |

After 3:1 propensity matching, 416 recipients were identified (CSS: 312; EVLP: 104). Groups were well matched for recipient demographics and donor characteristics (Tables 4 and 5). Similar to the unmatched analysis, EVLP donors had significantly lower PF ratios (P < 0.001) and were more likely to be DCD (30.5% vs 7.8%, P < 0.001). Post-operative outcomes were similarly higher in the EVLP group including a higher dialysis requirement (14.6% vs 7.4%, P = 0.046), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use (16.5% vs 8.3%, P = 0.03), prolonged ventilator use (35.3% vs 22.3%, P = 0.02), and incidence of treated rejection in the first year (30.9% vs 12.7%, P = 0.002). No significant differences in in-hospital mortality (8.7% vs 7.3%, P = 0.798) or length of stay (P = 0.278) were observed (Tables 3 and 6).

| Variable | Overall (n = 416) | Cold static storage (n = 312) | Ex vivo lung perfusion (n = 104) | P value |

| Age | 62 (55.8, 67) | 62 (55.8, 67) | 63 (55.5, 68) | 0.621 |

| Male sex | 244 (58.7) | 183 (58.7) | 61 (58.7) | 0.999 |

| Race | 0.92 | |||

| White | 305 (73.3) | 229 (73.4) | 76 (73.1) | |

| Black | 44 (10.6) | 32 (10.3) | 12 (11.5) | |

| Other | 67 (16.1) | 51 (16.3) | 16 (15.4) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.4 (23, 29.2) | 26.4 (23, 29.2) | 26.4 (23.6, 29.3) | 0.75 |

| Diabetes | 95 (22.8) | 73 (23.4) | 22 (21.2) | 0.736 |

| Former smoker | 236 (56.7) | 171 (54.8) | 65 (62.5) | 0.209 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/minute/1.73 m2) | 93.8 (76, 121.1) | 93.2 (76, 118) | 97.6 (76.5, 125.5) | 0.54 |

| Mean pulmonary artery pressure (mm Hg) | 24 (20, 31) | 24 (19, 31) | 24 (21, 31.5) | 0.457 |

| Diagnosis | 0.999 | |||

| Cystic fibrosis/immunodeficiency | 12 (2.9) | 9 (2.9) | 3 (2.9) | |

| Obstructive lung disease | 114 (27.4) | 86 (27.6) | 28 (26.9) | |

| Pulmonary vascular disease | 20 (4.8) | 15 (4.8) | 5 (4.8) | |

| Restrictive lung disease | 270 (64.9) | 202 (64.7) | 68 (65.4) | |

| Lung allocation score | 40.5 (34.9, 52.7) | 40.4 (34.6, 52.8) | 40.5 (35.4, 52.2) | 0.987 |

| Hospitalized prior to transplant | 0.992 | |||

| Not hospitalized | 324 (77.9) | 243 (77.9) | 81 (77.9) | |

| Hospitalized | 35 (8.4) | 26 (8.3) | 9 (8.7) | |

| In intensive care unit | 57 (13.7) | 43 (13.8) | 14 (13.5) | |

| Pre-operative ventilator | 18 (4.3) | 15 (4.8) | 3 (2.9) | 0.578 |

| Pre-operative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 24 (5.8) | 20 (6.4) | 4 (3.8) | 0.466 |

| Days on wait list | 38 (12, 123) | 34.5 (12, 121.8) | 41.5 (13.8, 123) | 0.765 |

| Variable | Overall (n = 416) | Cold static storage (n = 312) | Ex vivo lung perfusion (n = 104) | P value |

| Age | 38 (27, 51) | 38.5 (28, 51) | 38 (25, 51.2) | 0.708 |

| Male sex | 250 (60.1) | 186 (59.6) | 64 (61.5) | 0.817 |

| Coronary artery disease | 27 (6.5) | 22 (7.1) | 5 (4.9) | 0.58 |

| Smoking history | 41 (10) | 29 (9.5) | 12 (11.5) | 0.677 |

| Recent cocaine use | 98 (23.6) | 75 (24.1) | 23 (22.1) | 0.209 |

| Diabetes | 41 (9.9) | 30 (9.6) | 11 (10.6) | 0.924 |

| Hypertension | 116 (27.9) | 88 (28.2) | 28 (26.9) | 0.9 |

| Alcohol abuse | 95 (23.1) | 77 (25.1) | 18 (17.3) | 0.136 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.2 (23.7, 30.8) | 27.3 (24.1, 30.7) | 27 (22.9, 32.1) | 0.544 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 446 (394, 503.1) | 453.5 (400, 504.2) | 409 (360, 488.2) | 0.001 |

| Donor cause of death | 0.252 | |||

| Neuro (seizure/cerebral vascular accident) | 118 (28.4) | 91 (29.2) | 27 (26.2) | |

| Drug overdose | 58 (14) | 48 (15.4) | 10 (9.7) | |

| Asphyxiation | 20 (4.8) | 12 (3.8) | 8 (7.8) | |

| Cardiovascular | 41 (9.9) | 31 (9.9) | 10 (9.7) | |

| Trauma (gun shot wound/stab/blunt) | 154 (37.1) | 113 (36.2) | 41 (39.8) | |

| Drowning | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Other | 23 (5.5) | 17 (5.4) | 6 (5.8) | |

| Donation after circulatory death | 56 (13.5) | 25 (8) | 31 (29.8) | < 0.001 |

| Variable | Overall (n = 416) | Cold static storage (n = 312) | Ex vivo lung perfusion (n = 104) | P value |

| Center volume | 32 (14, 56) | 32 (14, 56) | 32 (14, 56) | 0.761 |

| Center volume yearly | 2.1 (0.9, 3.7) | 2.1 (0.9, 3.7) | 2.1 (0.9, 3.7) | 0.761 |

| Perfused by | ||||

| Organ perfusion organization | 0 (N/A) | 2 (1.9) | ||

| Transplant program | 0 (N/A) | 61 (59.2) | ||

| External perfusion center | 0 (N/A) | 40 (38.8) | ||

| Perfusion time | 294.5 (217, 507) | |||

| Warm ischemic time | 24 (19.7, 28.5) | 23 (18, 26) | 25 (20, 30) | 0.129 |

| Type of lung transplant | 0.009 | |||

| Bilateral | 319 (76.7) | 228 (73.1) | 91 (87.5) | |

| Right single | 40 (9.6) | 36 (11.5) | 4 (3.8) | |

| Left single | 57 (13.7) | 48 (15.4) | 9 (8.7) | |

| Distance traveled (nautical miles) | 894 (826, 1006.2) | 900 (825.5, 1000.8) | 892 (826.8, 1062.8) | 0.862 |

| Ischemic time (hours) | 7.7 (6.4, 10.3) | 7.1 (6.1, 8.2) | 13.6 (10.8, 16.2) | < 0.001 |

| Length of stay (days) | 19 (13, 37) | 19 (13, 35.8) | 22 (14, 48.5) | 0.278 |

| In-hospital mortality | 31 (7.7) | 22 (7.3) | 9 (8.7) | 0.798 |

| Postop dialysis | 38 (9.2) | 23 (7.4) | 15 (14.6) | 0.046 |

| Postop stroke | 18 (4.3) | 14 (4.5) | 4 (3.8) | 0.99 |

| Airway dehiscence | 10 (2.4) | 10 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 0.139 |

| Post-operative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 43 (10.4) | 26 (8.3) | 17 (16.5) | 0.03 |

| Post-operative ventilator | 0.02 | |||

| None | 6 (1.5) | 4 (1.3) | 2 (2) | |

| < 2 days | 213 (51.8) | 173 (56) | 40 (39.2) | |

| 2-5 days | 87 (21.2) | 63 (20.4) | 24 (23.5) | |

| 5+ days | 105 (25.5) | 69 (22.3) | 36 (35.3) | |

| Primary graft dysfunction grade 3 | 59 (14.2) | 45 (14.4) | 14 (13.5) | 0.935 |

| Acute rejection (hospitalization) | 0.052 | |||

| Yes and treated with immunosuppressant | 26 (6.2) | 15 (4.8) | 11 (10.6) | |

| Yes and not treated with Immunosuppressant | 4 (1) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (1.9) | |

| No | 386 (92.8) | 295 (94.6) | 91 (87.5) | |

| Treated rejection (1st year) | 44 (17.7) | 23 (12.7) | 21 (30.9) | 0.002 |

| Cause of death | 0.625 | |||

| Graft failure | 17 (18.1) | 14 (18.7) | 3 (15.8) | |

| Malignancy | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Cardio/cerebrovascular | 13 (13.8) | 9 (12) | 4 (21.1) | |

| Pulmonary | 16 (17) | 12 (16) | 4 (21.1) | |

| Infection | 31 (33) | 24 (32) | 7 (36.8) | |

| Other | 16 (17) | 15 (20) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Year of transplant | ||||

| 2018 | 44 (10.6) | 31 (9.9) | 13 (12.5) | |

| 2019 | 69 (16.6) | 49 (15.7) | 20 (19.2) | |

| 2020 | 88 (21.2) | 71 (22.8) | 17 (16.3) | |

| 2021 | 99 (23.8) | 70 (22.4) | 29 (27.9) | |

| 2022 | 109 (26.2) | 87 (27.9) | 22 (21.2) | |

| 2023 | 7 (1.7) | 4 (1.3) | 3 (2.9) |

Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated no significant difference in midterm survival between EVLP and CSS recipients in the unmatched cohort (P = 0.18) (Figure 1A). This finding remained unchanged in the propensity-matched cohort, where EVLP and CSS recipients exhibited similar survival (P = 0.08) (Figure 1B). These results suggest that, despite increased early post-transplant morbidity, EVLP does not appear to impact midterm survival compared to CSS.

Organ preservation is rapidly changing with the advent of extended perfusion, advanced cooler technology, and 10 °C preservation[2,5,6]. In this era dominated by technological advances, are traditional methods of preservation even relevant? Here we show that for organs traveling greater than 750 NM, traditional CSS can still offer benefits compared to EVLP including decreased peri-operative morbidity and similar mid-term survival. Though the ischemic time limitations of CSS are evident in this study (6-8 hours), this is still about 2 hours longer than initially described[1]. This finding highlights the relationship between transport distance and CIT. Ultimately, these results are encouraging for smaller transplant programs, or even those abroad in low resource locations, who do not have access to advanced preservation methods and might be dissuaded from traveling far distances to retrieve donors. The goal of any transplant provider is to expand the donor pool so that this therapy becomes more equitable and achievable for all. These results provide important information to providers who lack EVLP or even advanced coolers and should not dissuade transplant programs from retrieving organs at extended distances if ischemic times can be kept below 8 hours.

The observed increased ischemic time observed in the EVLP group is possibly due to the inherent processes of the EVLP procedure including cannulation, perfusion assessment, and interventions (e.g. bronchoscopy) before tran

Although this study has many strengths, there are some limitations. Foremost, the UNOS database has inherent limitations including lack of granular data, its retrospective nature, and its subject to information and selection bias. Due to this, we are unable to identify if any donors underwent preservation in advanced coolers[5].

With the advent of 10 °C preservation[6], what is the role of EVLP in preservation going forward? Though either technology comes with added associated costs, advanced coolers will always be less resource intensive than EVLP[4]. Providers must continue to optimize EVLP practices and perfusion techniques in order to keep this technology relevant in today’s era and must strive to perfect EVLP’s ability to resuscitate and rehabilitate damaged donor organs. Elective lung transplant may soon become a reality; however, providers must continue to optimize all technologies at their disposal to safely increase ischemic time. Understanding how transport distances translate into CIT across different preservation strategies will additionally be essential for optimizing donor lung utilization and ensuring equitable access to transplantation. Future research is necessary in order to determine optimal preservation in donor organs with extended travel distances or ischemic times so that lung transplantation can become a more equitable therapy for all parties: Surgeons, staff and patients.

While there was no significant difference in survival, EVLP patients had increased peri-operative morbidity. With the advent of changes in CSS with 10 °C storage further analysis is necessary to evaluate the best methods for utilizing organs from increased distances.

| 1. | Grimm JC, Valero V 3rd, Kilic A, Magruder JT, Merlo CA, Shah PD, Shah AS. Association Between Prolonged Graft Ischemia and Primary Graft Failure or Survival Following Lung Transplantation. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:547-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ali A, Nykanen AI, Beroncal E, Brambate E, Mariscal A, Michaelsen V, Wang A, Kawashima M, Ribeiro RVP, Zhang Y, Fan E, Brochard L, Yeung J, Waddell T, Liu M, Andreazza AC, Keshavjee S, Cypel M. Successful 3-day lung preservation using a cyclic normothermic ex vivo lung perfusion strategy. EBioMedicine. 2022;83:104210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mallea JM, Hartwig MG, Keller CA, Kon Z, Iii RNP, Erasmus DB, Roberts M, Patzlaff NE, Johnson D, Sanchez PG, D'Cunha J, Brown AW, Dilling DF, McCurry K. Remote ex vivo lung perfusion at a centralized evaluation facility. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022;41:1700-1711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peel JK, Keshavjee S, Naimark D, Liu M, Del Sorbo L, Cypel M, Barrett K, Pullenayegum EM, Sander B. Determining the impact of ex-vivo lung perfusion on hospital costs for lung transplantation: A retrospective cohort study. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023;42:356-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Neto D, Guenthart B, Shudo Y, Currie ME. World's first en bloc heart-lung transplantation using the paragonix lungguard donor preservation system. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2023;18:131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ali A, Hoetzenecker K, Luis Campo-Cañaveral de la Cruz J, Schwarz S, Barturen MG, Tomlinson G, Yeung J, Donahoe L, Yasufuku K, Pierre A, de Perrot M, Waddell TK, Keshavjee S, Cypel M. Extension of Cold Static Donor Lung Preservation at 10°C. NEJM Evid. 2023;2:EVIDoa2300008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Aboelnazar N, Himmat S, Freed D, Nagendran J. Ex-Vivo Lung Perfusion: From Bench to Bedside. In: Abdeldayem H, El-Kased A, El-Shaarawy E, editor. Frontiers in Transplantology. London: IntechOpen, 2016. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Ahmad K, Pluhacek JL, Brown AW. Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion: A Review of Current and Future Application in Lung Transplantation. Pulm Ther. 2022;8:149-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aigner C, Slama A, Hötzenecker K, Scheed A, Urbanek B, Schmid W, Nierscher FJ, Lang G, Klepetko W. Clinical ex vivo lung perfusion--pushing the limits. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1839-1847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |