Published online Jun 18, 2025. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v15.i2.98620

Revised: October 24, 2024

Accepted: December 9, 2024

Published online: June 18, 2025

Processing time: 234 Days and 20 Hours

The colon is the hollow viscera that proportionally has the lowest vascular supply and is more predisposed to ischemic colitis. In the context of end-stage liver disease, various components may explain this group's greater predisposition to colonic ischemic events. Furthermore, portal hypertension generates a process of coagulopathy, impairing local vascularization. This case report describes a case of ischemic colitis with small-vessel occlusion found during liver transplantation in a patient with decompensated end-stage liver disease.

A 64-year-old man with liver cirrhosis due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The patient underwent liver transplantation due to hepatic decompensation. The donor was a 53-year-old man who had died of a hemorrhagic stroke. Cavitary examination revealed diffuse ischemic colitis with significant distention and necrosis. Due to the condition of the colon, a subtotal colectomy was performed. Liver transplantation with warm ischemia time of 35 minutes, cold ischemia of 6 hours 30 minutes and total ischemia time of 7 hours 5 minutes. The patient improved clinically with oral tract function and physiotherapy, but unfortunately, he developed a bloodstream infection, a new septic shock and died six months after surgery.

Simultaneous total colectomy and orthotopic liver transplantation represent a rare situation. Ischemic events have a high mortality rate in the general population and are particularly important in cirrhotic patients.

Core Tip: This article described simultaneous colectomy and liver transplantation. Despite its rarity, this event should be known by transplant team surgeons, given the high mortality this condition might have.

- Citation: Kasputis Zanini LY, Lima FR, Fernandes MR, Alvarez PSE, Silva MS, Martins Filho APR, Franzini TAP, Nacif LS. Ischemic colitis with small-vessel occlusion, simultaneous total colectomy and liver transplantation: A case report. World J Transplant 2025; 15(2): 98620

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v15/i2/98620.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v15.i2.98620

Ischemic colitis is a condition related to an imbalance between blood supply and demand into the colon. The colon is the hollow viscera that proportionally has the lowest vascular supply and is more predisposed to ischemia[1].

In the context of end-stage liver disease, various components may explain this group's greater predisposition to colonic ischemic events[2]. Despite deficits in some components of the extrinsic coagulation pathway, cirrhotic patients have a procoagulant tendency[2-4]. Furthermore, portal hypertension generates a process of coagulopathy, impairing local vascularization[2,5].

This case report describes an unprecedented case of ischemic colitis with small-vessel occlusion found during liver transplantation in a patient with decompensated end-stage liver disease.

The patient referred to emergency medical service presenting with reduced diuresis, tense and voluminous ascites, psychomotor agitation and mental confusion.

A 64-year-old male who had been previously diagnosed with liver cirrhosis due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). This patient was already listed for liver transplantation and in the follow-up for a routine outpatient visit he was displaying reduced diuresis, tense and voluminous ascites, psychomotor agitation and mental confusion. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD)-sodium calculated out of decompensation (2 months before admission) was 16.

The patient was referred to the emergency room, and blood culture and urine culture were collected. He was admitted to intensive care for clinical compensation. All infectious tests and images [computed tomography (CT) imaging] were taken and discarded signs of infection. The MELD calculated in the context of decompensation was 34. Four days later the intensive care treatment of an organ was available for transplantation.

The organ donor was a 53-year-old male who had died from a hemorrhagic stroke. Our patient underwent an orthotopic liver transplant with an organ weighing 1000 g.

Patient previously diagnosed with liver cirrhosis due to NASH and HCC. He was already listed for liver transplantation when he developed decompensated liver disease.

He had already been diagnosed with metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus and hypertension. There was no noteworthy family history for the present case.

He was in a poor general condition, dehydrated, jaundiced and acyanotic. In addition, some significant changes were observed, such as: (1) Tense and voluminous ascites (with no signs of peritonitis); (2) Psychomotor agitation; (3) Flapping; and (4) Mental confusion.

Our patient was referred to the emergency room, and blood culture and urine culture were collected. Subsequent blood culture and uroculture results were negative. He was admitted to intensive care for clinical compensation. All laboratory tests ruled out current infectious processes.

A contrast CT scan on admission showed a cirrhotic liver, with voluminous ascites and no evidence of portal thrombosis. The colon had some degree of distension, but no obstructive factors were identified. A chest CT scan showed no signs of pulmonary infection.

This patient had already been diagnosed with liver cirrhosis (caused by NASH) and HCC. He underwent liver tran

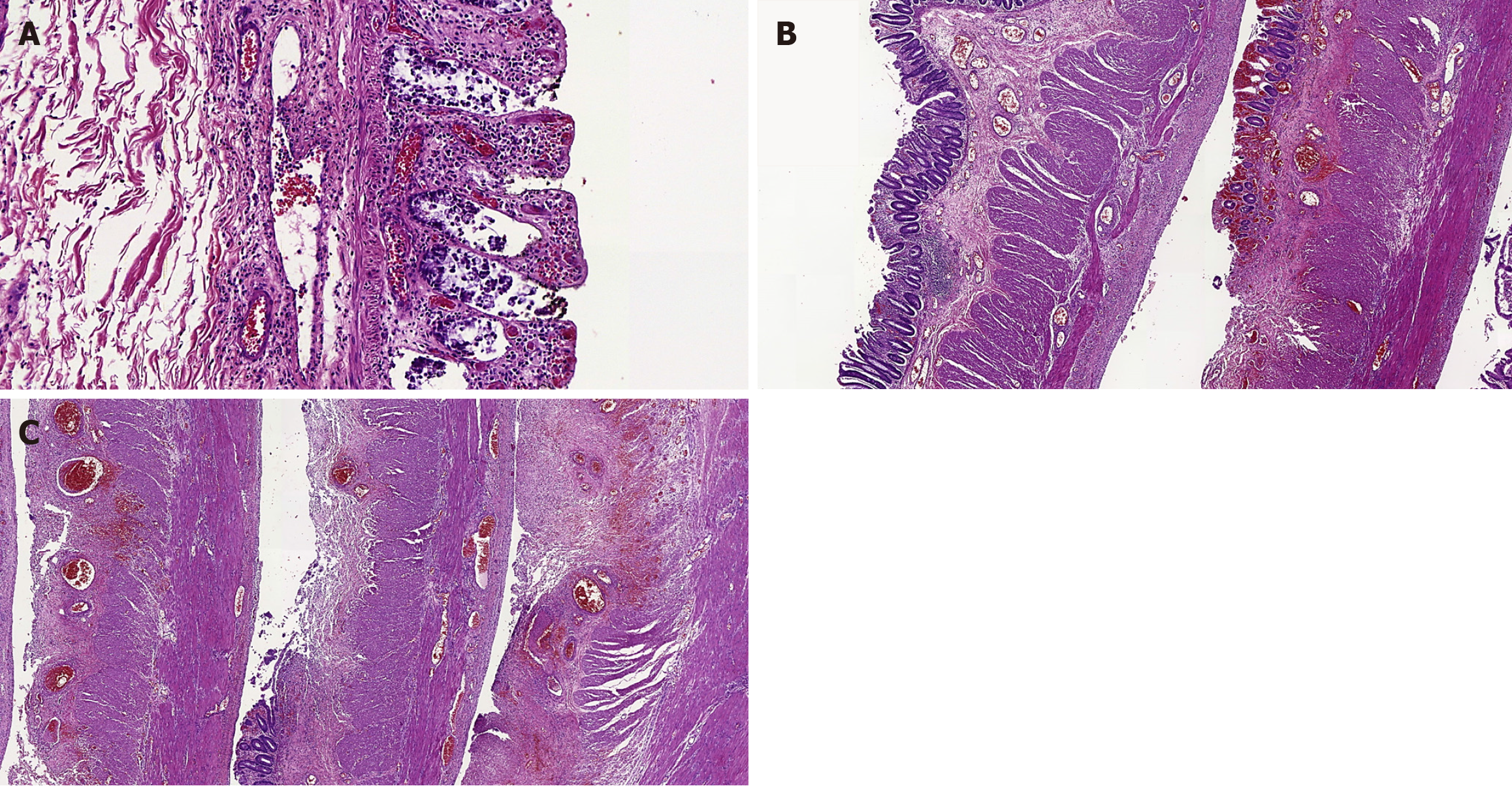

On gross examination, the resected colon exhibited brown and purple color, walls thinner than normal and lumen dilation. The mucosa was granular, darkish brown and purple, with some linear ulcers and areas of grayish green necrosis. Histologically, there were different ischemic lesions usually with patchy involvement, such as: Early mucosal changes (involving superficial parts of crypts), erosions, ulcers (sometimes with pseudomembranes), variable mucosal necrosis, edema with hemorrhage, congested lamina propria, some crypt abscesses, multiple fibrin thrombi especially in mucosal vessels, areas with regenerative epithelium, neutrophilic inflammatory response, occasional submucosal necrosis and only focal deeper injury to the bowel wall (Figure 1).

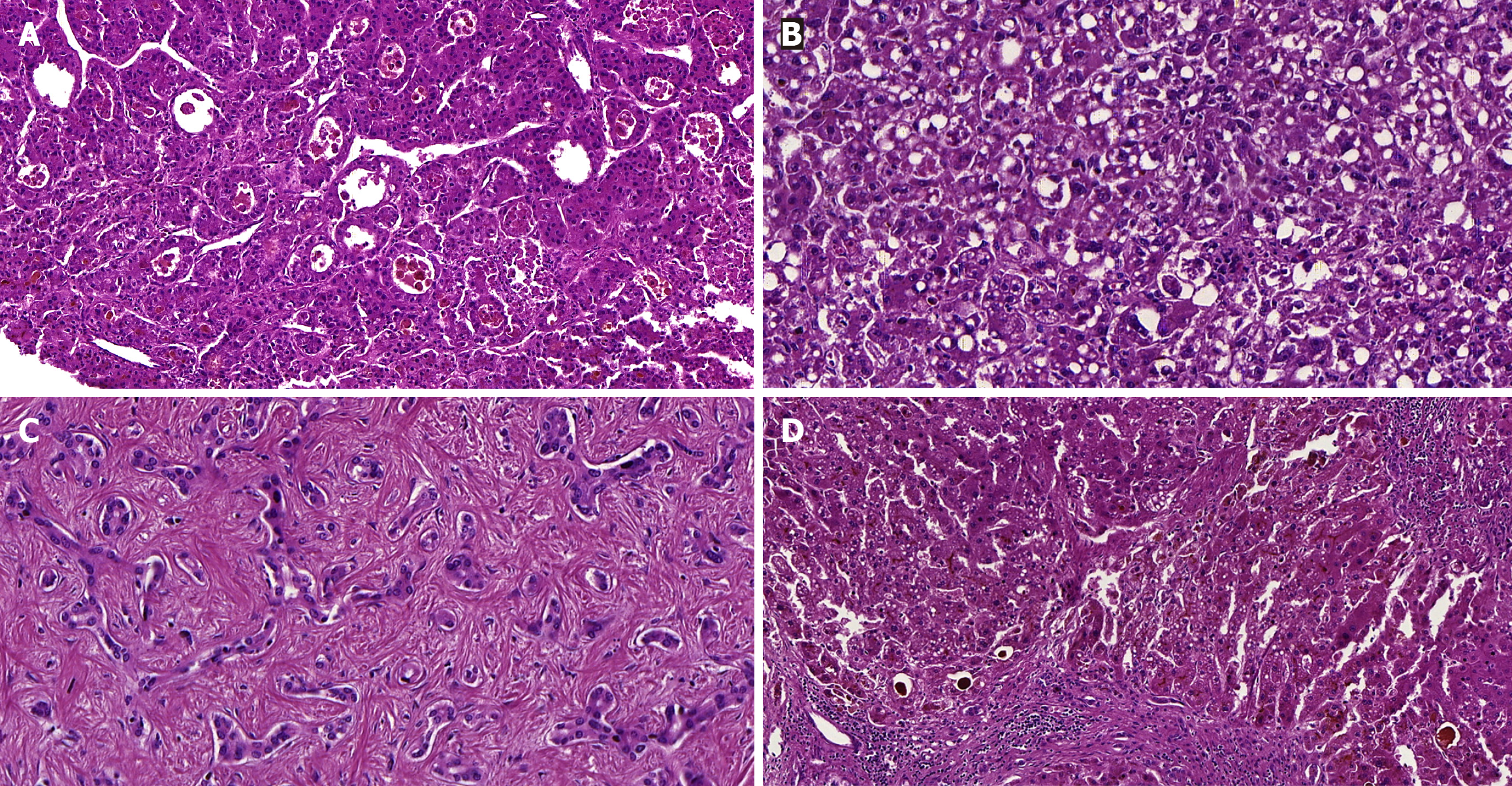

The gross appearance of the explanted liver was shrunken and had a nodular surface. On slicing, the cut surface depicted tan color and mixed cirrhosis (with micronodules and macronodules). Some nodules were well-demarcated masses, with or without a capsule, variably tan and green, which measured between 1 cm and 2.3 cm. Microscopically, the cirrhotic parenchyma had significant bilirubinostasis and features of steatohepatitis, including steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, inflammation and Mallory-Denk bodies. The neoplastic nodules with HCC were moderately differentiated and showed trabecular and pseudoglandular patterns. There were areas with characteristics of the steatohepatitis subtype and also coagulative necrosis (which suggested previous treatment). Only neoplastic microvascular invasion was identified. Additionally, a one-centimeter nodule with low-grade cholangiolocarcinoma, a subtype of small duct intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, was also found in the liver (Figure 2).

Four days later the intensive care treatment of an organ was available for transplantation. The organ donor was a 53-year-old male who had died from a hemorrhagic stroke. Our patient underwent an orthotopic liver transplant with an organ weighing 1000 g.

A Makuuchi J-shaped incision was made. An inventory of the cavity revealed diffuse ischemic colitis with significant distension and necrosis, and a moderate amount of citrine ascitic fluid in the peritoneal cavity. The liver exhibited a cirrhotic appearance. The liver transplant had warm ischemia time of 35 minutes, cold ischemia of 6 hours 30 minutes and total ischemia time of 7 hours 5 minutes. During the procedure, a temporary portocaval shunt was performed.

A total colectomy was carried out using a harmonic scalpel and separate ligatures, with the option of making a terminal ileostomy and burying the rectal stump.

The patient was referred to the intensive care unit intubated and taking a vasoactive drug. Extubation was attempted on the 4th postoperative day, but it failed. A tracheostomy was performed on the 8th postoperative day, given the difficulty in extubation.

The patient developed a pulmonary focus of infection and a parapneumonic pleural effusion requiring chest drainage with a water seal. He continued on dialysis with renal dysfunction. Our patient remained hospitalized due to subsequent infectious complications, including a Shilley catheter infection leading to septic shock.

On the 42nd postoperative day, the patient's leukocytes count worsened again, his C reactive protein (CRP) rose and he had a fever of 39 ºC. A CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis (contrasted) was ordered to investigate an infectious focus. Consolidation of the right lower lobe and a pelvic collection suggestive of rectal stump dehiscence were revealed.

The following day he underwent ultrasound-guided drainage of the pelvic collection, which showed purulent contents. We opted for proctosigmoidoscopy with placement of a vacuum dressing for the rectal stump. He remained with the device for 20 days and had an effective therapeutic response, with only a small collection, which was drained by ultrasound. He remained in intensive care on antibiotics and intermittent hemodialysis.

On the 74th postoperative day, the dose of Tacrolimus had to be increased because the patient’s canalicular enzymes were high, which stabilized the blood levels subsequently. He still needed intermittent hemodialysis and antibiotic therapy to treat lung infection.

On the 75th postoperative day, he had a new rise in CRP, hyperactivity and the need to use vasoactive drugs, albeit at a low dose. A new chest CT scan showed left-sided bronchopneumonia. Antibiotic therapy was stepped up. The infection improved afterwards.

With clinical improvement, on the 80th postoperative day he sat up in the armchair and was not using vasoactive drugs, but continued to show worsening evidence of hepatocellular damage, which made us opt for pulse therapy.

Due to persistent worsening of bilirubin, increase of canalicular enzymes and evidence of hepatocellular injury, the decision was made to perform cholangioresonance with magnetic resonance imaging of the upper abdomen. Bile duct stenosis was found, associated with dilation of the intrahepatic bile duct.

On the following day, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was indicated, with placement of a metal prosthesis due to ectasia of the hepatocoledochus and angulation of the anastomosis.

The patient was improving clinically with oral tract function and physiotherapy, but unfortunately he developed a bloodstream infection and a new septic shock. He ultimately died six months following surgery.

Cirrhotic patients are subject to a number of possible complications. Furthermore, the end-stage of liver disease imposes a series of dysfunctions that involve microvascular and macrovascular impairments, paradoxically resulting in coagulopathy and thrombophilia. This case report describes an unprecedented case of ischemic colitis with small-vessel occlusion found during liver transplantation in a patient with decompensated end-stage liver disease.

In end-stage liver disease, there is a reduction in protein C titers associated with an increase in factor VIII levels, which causes an imbalance in the coagulation system, generating a prothrombotic effect. This situation is often translated into portal thrombosis or thrombosis of other sites[3]. Small vessel ischemic colitis in cirrhotic patients is multifactorial: (1) Procoagulant tendency combined with local vascular dysfunction (promoted by portal hypertension) generates archi

Portal hypertensive coagulopathy is a potentially asymptomatic condition with an estimated prevalence of 25%-70% of cirrhotic patients[6-8]. It was first described by Naveau et al[5] in 1991. This condition leads to ectasia of the venous system, resulting in alterations in the local colonic vascularization. The architectural alterations and ectasia generate a propensity for stasis and increased pressure in arterial beds, potentially contributing to ischemic events in small vessels.

In the literature, we can find an association between chemoembolization for hepatocarcinoma and the occurrence of small vessel ischemic colitis[9,10]. The patient in this report had not previously undergone chemoembolization or other therapies for HCC. Strangely, the anatomopathological analysis found extensive coagulative necrosis in one of the hepatic nodules (a typical finding of previously treated nodules).

The association and discussion between colectomy and liver transplantation is widely debated in the spectrum of primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease. In general, colectomies precede liver transplantation[11]. The patient in question had acute-on-chronic liver failure and was transplanted after clinical compensation. The cause-effect is still unclear. The ischemic process may have triggered the decompensation, but the decompensation itself may have led to the ischemic event.

It was an extremely rare situation because total colectomy was performed simultaneously with orthotopic liver transplantation in this singular case.

In the series published by Salimi et al[12], 5 procedures were performed after implantation of the liver graft. This small sample reflects the success of this type of surgical strategy. Two of these colectomies were performed in the context of inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease), specifically in this condition, where there is data (albeit conflicting and of a low level of evidence) showing that the removal of the colon from patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory disease would result in fewer complications, mainly related to thrombotic events of the graft (portal vein thrombosis or arterial thrombosis) and related to immunosuppression[13].

Our patient's pre-transplant conditions were already delicate, leading to a high surgical risk and basically higher morbidity and mortality. However, the intraoperative need for colectomy was imperative, and it was feasible for our experienced team.

Ischemic events have a high mortality rate in the general population and are particularly important in cirrhotic patients. This article described simultaneous colectomy and liver transplantation. Despite its rarity, transplant team surgeons should be aware of this event, given the high mortality this condition might have.

| 1. | Green BT, Tendler DA. Ischemic colitis: a clinical review. South Med J. 2005;98:217-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Then E, Lund C, Uhlenhopp DJ, Sunkara T, Gaduputi V. Cirrhosis Is Associated With Worse Outcomes in Ischemic Colitis: A Nationwide Retrospective Study. Gastroenterology Res. 2020;13:253-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tripodi A, Anstee QM, Sogaard KK, Primignani M, Valla DC. Hypercoagulability in cirrhosis: causes and consequences. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1713-1723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tripodi A, Fracanzani AL, Primignani M, Chantarangkul V, Clerici M, Mannucci PM, Peyvandi F, Bertelli C, Valenti L, Fargion S. Procoagulant imbalance in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;61:148-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Naveau S, Bedossa P, Poynard T, Mory B, Chaput JC. Portal hypertensive colopathy. A new entity. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1774-1781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Urrunaga NH, Rockey DC. Portal hypertensive gastropathy and colopathy. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18:389-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Misra SP, Dwivedi M, Misra V. Prevalence and factors influencing hemorrhoids, anorectal varices, and colopathy in patients with portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 1996;28:340-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bresci G, Parisi G, Capria A. Clinical relevance of colonic lesions in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 2006;38:830-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Selzman J, Gajendran M, El Kurdi B, Katabathina V, Wright R, Umapathy C, Echavarria J. Transarterial Chemoembolization-Induced Ischemic Colitis: A Rare Complication Due to Nontarget Embolization. ACG Case Rep J. 2023;10:e01140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yamamoto S, Onishi H, Oyama A, Takaki A, Okada H. Severe Colitis Caused by Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy with Cisplatin for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Intern Med. 2020;59:69-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nordenvall C, Olén O, Nilsson PJ, von Seth E, Ekbom A, Bottai M, Myrelid P, Bergquist A. Colectomy prior to diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis is associated with improved prognosis in a nationwide cohort study of 2594 PSC-IBD patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:238-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Salimi S, Pandya K, Sastry V, West C, Virtue S, Wells M, Crawford M, Pulitano C, McCaughan GW, Majumdar A, Strasser SI, Liu K. Impact of Having a Planned Additional Operation at Time of Liver Transplant on Graft and Patient Outcomes. J Clin Med. 2020;9:608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu K, Strasser SI, Koorey DJ, Leong RW, Solomon M, McCaughan GW. Interactions between primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease: implications in the adult liver transplant setting. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11:949-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |