MATERIALS AND METHODS

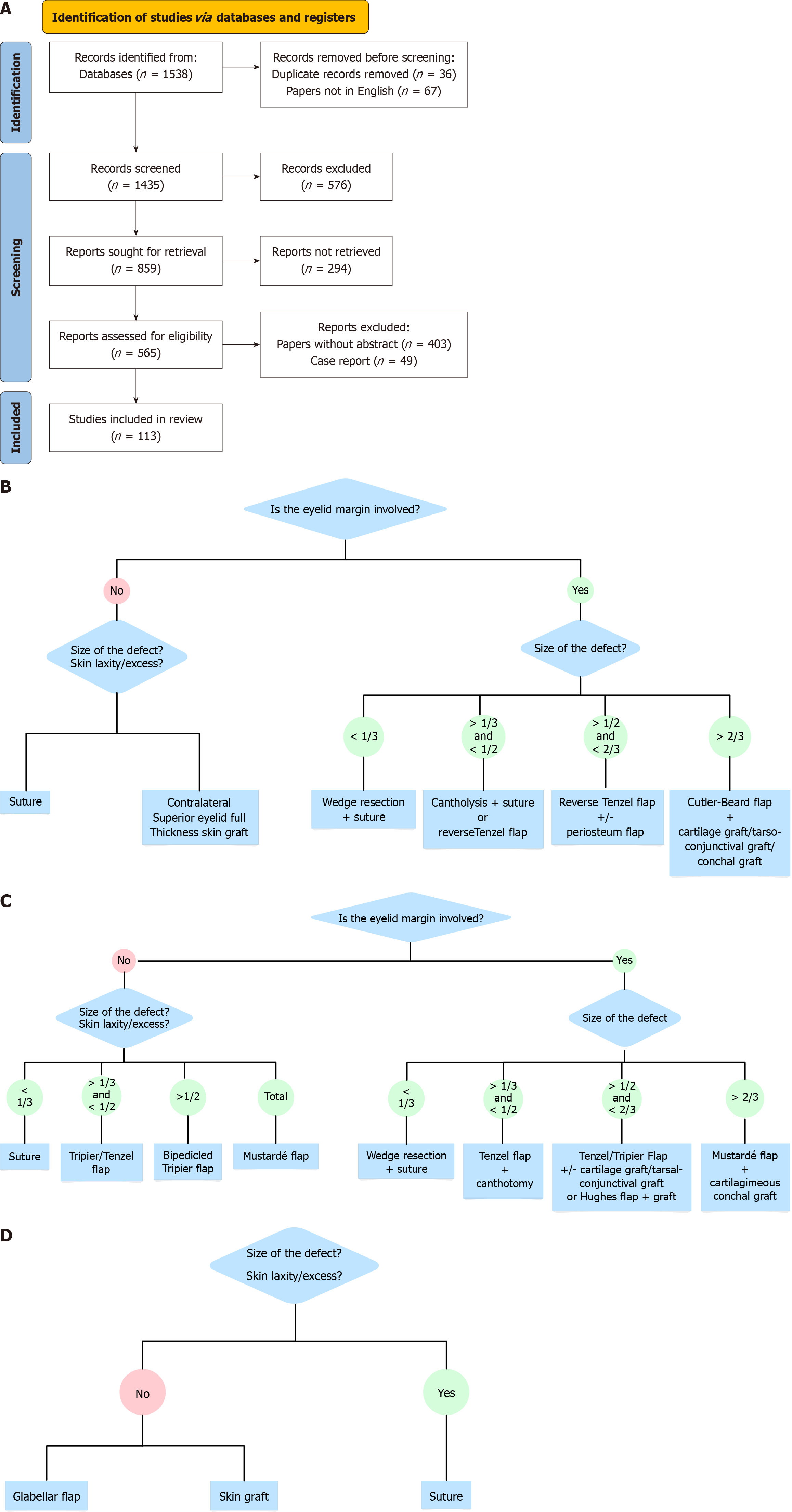

To develop a reconstructive algorithm for the eyelid region, a literature review of publications from the past 12 years (from December 1, 2011 to December 1, 2023) was conducted on Medline (PubMed). Algorithms and reconstructive techniques were searched using keywords such as “eyelid reconstruction and algorithm, grafts, flaps, tissue transplantation, autologous grafts, autologous tissues”. The literature review included only articles in English that referred to humans. A total of 1538 articles emerged from the initial screening. A second selection was made by considering only articles with abstracts and excluding case reports, resulting in 113 selected articles. Articles were included if they addressed human eyelid reconstruction and adhered to American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) quality standards. Each article was assigned a quality score using the ASPS’ guidelines for clinical studies. Figure 1A depicts the article selection procedure. Articles were evaluated based on design quality, outcome clarity, and bias mitigation, adhering to ASPS criteria for clinical research[5].

Figure 1 Eyelid reconstruction surgery after tumor removal and the use of a shared reconstruction flowchart.

A: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow chart showing search criteria; B: Our algorithm for upper eyelid reconstruction; C: Our algorithm for lower eyelid reconstruction; D: Our algorithm for internal canthus reconstruction.

Eyelid reconstruction surgeries post-oncological resection performed from December 1, 2021, to December 1, 2022 in the Department of Plastic Surgery of Cattinara Hospital in Trieste were considered conducted by the same surgical team (Giovanni Miotti and Federico Cesare Novati) using the shared reconstructive flow chart (Figure 1A-C). Ethical permission was obtained from the Cattinara Hospital Review Board. All participants granted informed consent for their involvement and the utilization of their images in this study. A uniform data collection form was employed, with independent verification conducted by two reviewers to ensure data accuracy. All patients received pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis with 2 g cefazolin (or 600 mg clindamycin if allergic to penicillin) when grafts were used and post-operative topical antibiotic prophylaxis with antibiotic-corticosteroid eye drops or gels (or only antibiotics if corticosteroids were contraindicated), and systemic antibiotics for major flaps, for a total of 7 days. Patients were monitored for an average duration of 150 days (range: 30-342 days). Complications were characterized as post-operative occurrences necessitating further surgery, such as infection, flap necrosis, and dehiscence. Algorithm development entailed classifying fault features and aligning them with suitable reconstruction approaches described in the literature. Each strategy was chosen based on its proven effectiveness in analogous instances. Data analysis was performed via SPSS (Version V.29) for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Chi-square tests and t-tests were utilized to compare complication rates and evaluate statistical significance. Algorithm validation was assessed through diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, underscoring its reliability as a clinical instrument.

RESULTS

Patient demographics

During the specified period, we performed 96 eyelid reconstruction surgeries following the removal of suspected neoplasms referred by colleagues in the Dermatology or Ophthalmology departments. The patients included were 53 women (55%) and 43 men (45%); patient ages varied from 45 years to 89 years, with a mean of 74 years (SD: 10.5 years, interquartile range: 65-80). Follow-up visits spanned 1-12 months, with an average of 150 days (minimum 30 days, maximum 342 days). The neoplasms involved the upper eyelid in 10 cases (10.4%), lower eyelid in 49 cases (51%), and the internal canthus 37 cases (38.6%). Only the anterior lamella was involved in 68% of cases (65 patients), while both eyelid lamellae were involved in 32% of cases (31 patients). From an anatomopathological diagnosis standpoint, 62 cases were basal cell carcinoma. There were also 18 cases of squamous cell carcinoma, 1 case of Merkel cell carcinoma, 1 case of undifferentiated spindle-cell sarcoma (later treated with orbital exenteration); 14 cases were diagnosed as non-malignant (benign lesions, non-melanoma pigmented neoplasms, precancerous lesions).

Reconstructive techniques

From a reconstructive technique standpoint, the procedures were divided as follows: 59 direct sutures, 34 reconstructions with local flaps, two reconstructions with skin grafts, one reconstruction with a dermal substitute, and 0 reconstructions with free flaps. Further subdividing the local flaps by technique, the Tenzel flap was the most used (14 cases; 14.5% of total cases, 41.1% of flap reconstructions), followed by the Tripier flap (10 cases, 10.4% of all reconstructions, 29.4% of those with flaps) and the glabellar flap (6 cases, 6.2% of all reconstructions and 17.6% of flap reconstructions). The Mustardé flap was used twice (2.1% and 5.9% of cases), and the V-Y advancement flap and the Limberg transposition flap were each used once (1% and 2.9%). In the 31 cases where the posterior lamella was involved, reconstruction was necessary in 9 cases. For this purpose, a periosteal flap from the lateral orbital rim was chosen in 5 cases (16.1%), a transconjunctival graft from the contralateral upper eyelid was used in 4 cases (12.9%), and a canthotomy allowed the advancement of mucosa to fill the residual defect in 2 cases (5.8%). In the remaining 20 cases, we opted not to rebuild the posterior lamella under the Mustardé flap because of anesthetic concerns. In the other 19 cases, the continuity of the lamella was restored by suturing the tarsal stumps (61.3%).

Follow-up and complications

We did not observe any significant complications in the treated cases (partial or total flap necrosis, lagophthalmos, and cicatricial ectropion, etc): Subgroup study of follow-up (≤ 3 months vs > 3 months) revealed no statistically significant difference in complication rates. We observed inflammatory reactions (conjunctivitis or conjunctival chemosis) in 10 cases (10.4%), which resolved with local medical treatment (antibiotic and corticosteroid eye drops) within 7 days. Two cases (2.1%) experienced partial wound dehiscence, both involving wedge resection of the lower eyelid with direct suture. One case (1%, lower eyelid reconstruction with a Limberg flap) had temporary malpositioning, a postoperative scleral show that almost wholly resolved at 6 months post-surgery, with a near-complete resolution of flap edema. There were no reports of infection. No reoperations were necessary for complications or lack of oncologic radicality. Validation investigation indicated a 10% reduction in complication rates compared to existing literature, hence affirming the algorithm’s efficacy in clinical use.

DISCUSSION

Eyelid reconstruction aims to restore the form and function of these critical structures that protect the eye and serve other physiological roles[6,7]. Few studies in the literature have aimed to create a decision-making algorithm for eyelid reconstruction[6,8,9]. Generally, case series are reported, presenting reconstructive models for specific defects, or more commonly, articles are based on defect width (usually greater or less than 1/3 of eyelid width)[10-12]. The subject matter considers the entire eyelid region, with some dividing it into sub-areas[6], others considering the vertical extent of the defect[9], and still others considering the horizontal extent of the defect[8]. In this study, we formulated and validated an algorithm for eyelid reconstruction to enhance surgical outcomes. Our findings demonstrate a decrease in complications, highlighting the algorithm’s clinical significance. Our algorithm incorporates sophisticated reconstruction techniques, in contrast to existing models that predominantly focus on defect width or location without accounting for lamellar involvement. Our reconstructive algorithm is summarized in Figure 1B-D. We considered the three eyelid zones (the upper, lower, and internal canthus) separately. The extent of the defect was considered for each zone, and our reconstructive choice was indicated for each possibility.

Non-full-thickness defects of the upper eyelid

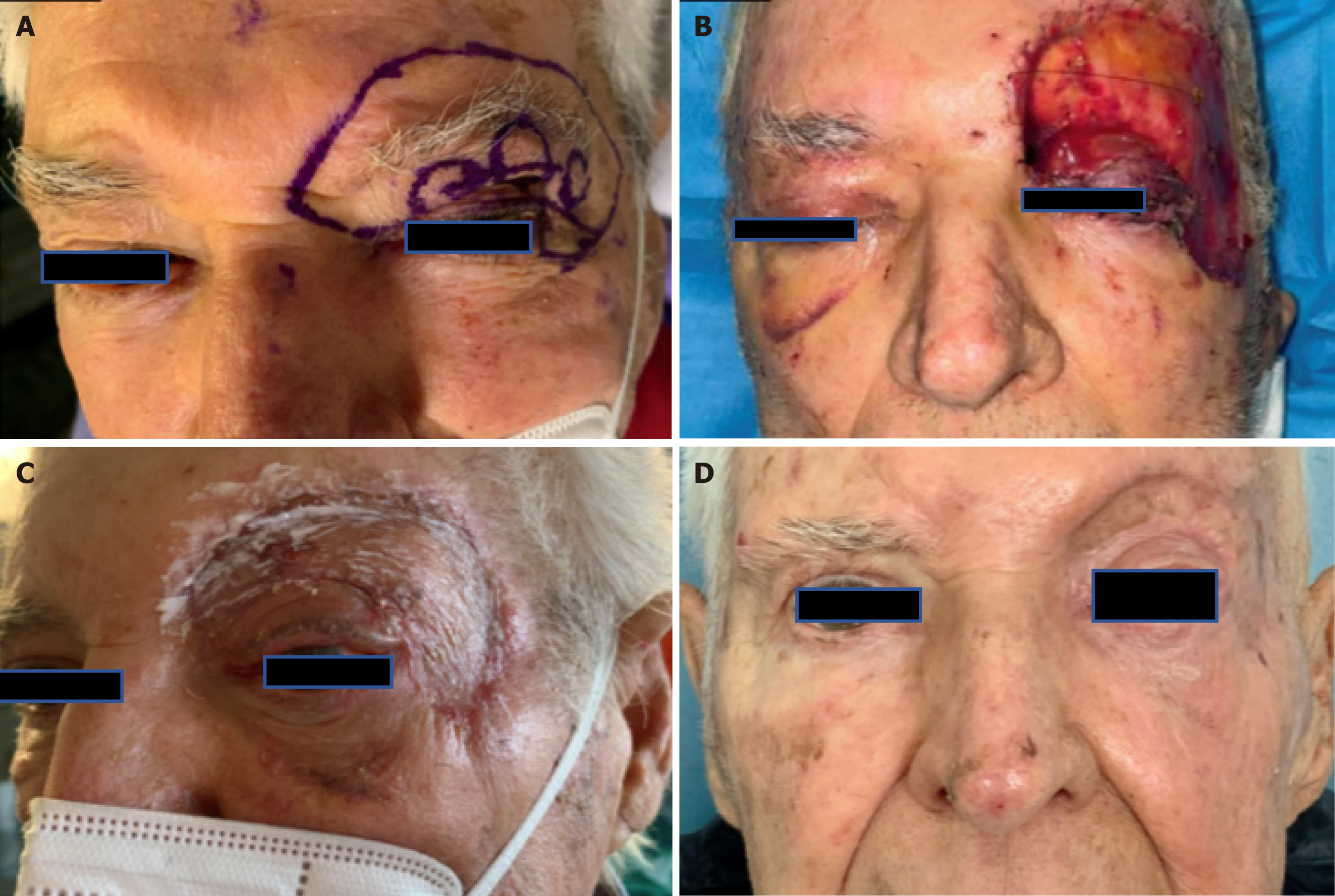

For the upper eyelid, when a defect involves only the anterior lamella, and the skin laxity does not permit direct suturing, the most effective and aesthetically preferred solution is a full-thickness skin graft[9,13]. We recommend the contralateral upper eyelid as the most adequate donor area[8]. When a defect involves both pretarsal and preseptal regions, some studies suggest that the two areas should be repaired separately. Specifically, some report that there should be two grafts, or, as described by Mukit et al[6], the preseptal portion could be repaired with a local flap, while the pretarsal portion with a skin graft. In our experience in 1 case (as shown in Figure 2), we had to reconstruct the entire eyelid-brow-temporal region following a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma. In this case, the neoplasm was localized within the anterior lamella of the left upper eyelid. After thoroughly evaluating the radiological images, which showed the disease confined to the subcutaneous region of the anterior lamella of the left upper eyelid, we radicalized the neoplasm. We widened it to 3 cm according to guidelines and removed the entire anterior lamella of the eyelid and the temporal and eyebrow regions. Preserving the posterior lamella of the eyelid allowed us to maintain the levator palpebrae muscle and, consequently, the eyelid closure mechanism. We then opted for a full-thickness graft taken from the right upper eyelid to reconstruct the anterior pretarsal lamella of the eyelid and the placement of a dermal substitute in the preseptal portion of the same and the temporal and eyebrow regions. Three weeks later, the dermal substitute was covered with a partial-thickness skin graft taken from the thigh. At the end of the reconstruction process, the patient maintained upper eyelid closure capability with minimal lagophthalmos of less than 2 mm at 1-month follow-up. Subsequent radiotherapy after surgery resulted in a minor adverse event of moderate skin retraction in the lateral canthal area, but mainly an inveterate corneal ulcer, necessitating a tarsorrhaphy. At 10 months post-operation, there were no clinical or instrumental signs of recurrence.

Figure 2 Reconstruction of the entire eyelid-brow-temporal area after Merkel cell carcinoma.

Patient consent was obtained for the utilization and publication of identifying photos, in accordance with ethical norms. A: Preoperative assessment of Merkel carcinoma (left upper eyelid); B: Post-operative (I stage); C: 10 days after II stage post-operative; D: 2 months follow-up.

Full-thickness defects of the upper eyelid

When both upper eyelid lamellae are involved, previous reports unanimously consider direct suturing the primary reconstructive choice[6,8]. In our experience, the limit for this technique is generally a defect of less than one-third of the eyelid width[14]. In certain instances, a lateral canthotomy or cantholysis may be required to facilitate medial mobilization of the remaining eyelid and enable direct closure[8].

Defects > 1/3 but < 2/3 of the eyelid width: Local flaps represent the gold standard when the residual defect is more significant than 1/3 but less than 2/3 of the eyelid width (less than 1/2 eyelid according to some authors). For upper eyelid reconstruction, the miotarsocutaneous flap described by Rosa et al[12] is one of the most commonly mentioned in the literature[6], as it allows for full-thickness defect reconstruction in a single stage without needing additional tissues for posterior lamella reconstruction. In this case, according to Chang et al[8] and in our own experience, the reverse semicircular Tenzel flap could be a valid solution without the need to reconstruct the posterior lamella. A modification of this procedure by Mandal et al[15], showed good and functional aesthetic results in term of color matching, flap robust vascularity, good uplift of upper lid, and satisfactory closure of the eyelids.

Defects > 2/3 of the eyelid width: For defects greater than 2/3 of the upper eyelid and full thickness, the reconstructive choice involves a combination of a local flap for the anterior lamella and a graft for the posterior lamella reconstruction. The most commonly used technique until the introduction of modifications is the Cutler-Beard flap, consisting of two surgical stages: (1) In the initial stage, a full-thickness composite flap consisting of conjunctiva, orbicularis muscle, and lower eyelid skin, excluding tarsus is translocated from the lower eyelid into the upper eyelid defect, positioned beneath a “bridge” of the lower eyelid margin; and (2) The subsequent surgical procedure entails detaching the flap within 3-8 weeks[8,16]. The main limitation of this flap is the potential lack of stability in the upper eyelid due to the lack of tarsus. To improve this aspect, the placement of a graft between the conjunctiva and orbicularis muscle of the flap has been successfully tested, as tissues such as sclera, cartilage, or acellular dermal matrices have been used[17,18]. In our experience, the Cutler-Beard flap combined with a tissue that ensures upper eyelid stabilization compensating for the absence of tarsus is the best solution for this type of reconstruction. We consider the auricular cartilage or tarso-conjunctival graft from the contralateral upper eyelid, described respectively by Mandal et al[19] and by Bengoa-González et al[20], the best possible solutions in terms of donor site morbidity. When this flap cannot be used, alternatives exist in the literature (e.g., Yazici et al[21]), using skin or myocutaneous flaps for the anterior lamella combined with a tarso-conjunctival or cartilage graft for the posterior lamella.

When reconstructing the posterior lamella of the eyelid with grafts, we must consider other available options: hard palate (mucoperiosteal graft), veins (venous graft, using propulsive veins), galea, and oral mucosa[1]. Exceptions limited to specific reconstructive needs and anatomical concerns could be two grafts in combination: two grafts positioned on the orbicularis muscle (“sandwich flap”) advancing into the defect, as described by Kakizaki et al[22] or the use of the tarso-conjunctival graft combined with a skin graft for the anterior lamella, as described by Bortz et al[23]. Tenland et al[24] published a possible use of the tarso-conjunctival graft combined with a skin graft for the anterior lamella, as the tarso-conjunctival graft could survive independently of a vascular connection.

Non-full-thickness defects of the lower eyelid

Defects of the lower eyelid affecting less than 1/3 of the anterior lamella alone can be repaired by direct suturing, utilizing skin laxity in this area and minimizing the risk of cicatricial retraction. If necessary, a lateral canthotomy with cantholysis can be performed to facilitate tissue mobilization[8]. Defects affecting 1/3 to half of the anterior lamella of the lower eyelid require repair with a flap. This is preferred over a skin graft because it is less prone to retraction. The Tripier myocutaneous flap, single or double pedicle, is the most commonly used solution in these cases according to the algorithms proposed by Chang et al[8], Mukit et al[6], and Elliot et al[25]. In our experience, we propose the double pedicle form to reconstruct up to 2/3 of the anterior lower eyelid. A possible alternative to this approach is the transposition flap according to Limberg or Dufourmentel, as described by Custer et al[10]. We reserve this approach where there is no available tissue in the temporal region or in cases where, primarily in men, mobilizing the temporal skin would mobilize the scalp or beard, creating asymmetry between the two halves of the face. Alternatively, for reconstructing non-full-thickness eyelid defects involving up to 2/3 of the eyelid, we propose the rotational flap from the temporal region described by Tenzel and Stewart[26]. In our experience, complete loss of the anterior lamella of the lower eyelid necessitates using a rotation flap from the cheek region capable of reaching even the medial extreme of the eyelid, the Mustardé flap. This solution implies potential downward contraction and sagging of the flap with eyelid eversion[27].

Full-thickness defects of the lower eyelid

When an excision extends to both palpebral lamellae, the reconstruction must consider the functions and anatomical characteristics of each. Defects smaller than 1/3 of the eyelid, or < 1/4 according to Iglesias et al[9], can be sutured directly[28].

Defects > 1/3 but < 1/2 of the eyelid width: The literature unanimously considers using a local flap necessary to repair full-thickness defects between 1/3 and 1/2 of the lower eyelid. Iglesias et al[9] proposed the direct suturing of a defect of this size facilitated by a lateral canthotomy. According to Chang et al[8] and our experience, the most suitable flap for this purpose is the Tenzel and Stewart[26]rotation flap, associated with a lateral canthotomy that allows for greater medialization of the tissues. If better stabilization of the lateral canthus is necessary, we usually sculpt a periosteal flap from the lateral orbital rim, as also described by Perry and Allen[29]. As a second option, in patients who do not have available recruitable tissues in the temporal region, we propose reconstruction with a rhomboid flap associated with a tarsal flap as suggested by Custer et al[10]. According to Mukit et al[6], the most suitable reconstruction method would be the double island flap (myocutaneous for the anterior lamella and mucosal for the posterior lamella) described by Garces et al[30]. If reconstruction using a local flap is not feasible in the lower eyelid, a reconstruction using a full-thickness skin graft, preferably extracted from the upper eyelid region, could be performed.

Defects > 1/2 but < 2/3 of the eyelid width: If the residual defect is greater than 50% of the eyelid, the most well-known and performed procedure is the two-stage reconstruction with a tarsoconjunctival pedicle flap, according to Hughes[31]. This reconstruction utilizes the upper tarsal lamella, from which 3-4 mm are harvested, connected to an overlying conjunctival bridge that maintains vitality. The reconstruction comprises two surgical phases. In the initial phase, the tarsoconjunctival flap is positioned into the posterior lamellar defect of the lower eyelid. The tarsoconjunctival flap may subsequently be covered with several types of skin flaps or a full-thickness skin graft to restore the associated anterior lamellar defect. In patients with adequate skin redundancy in the malar area, a cutaneous and muscular flap may be advanced superiorly to encompass the tarsoconjunctival flap. The second surgical stage, performed after approximately 4-6 weeks, involves detachment of the vascular pedicle. There is a greater likelihood of lower eyelid ectropion when the flap is separated from the upper eyelid before the usual 4-6 weeks interval. Despite this flap being easily reproducible and providing good functional results, there are several disadvantages: (1) The first is undoubtedly the occlusion of the eye itself for a period of 2 weeks to 6 weeks; (2) The second is the need for a second surgical procedure for flap autonomization; and (3) Permanent loss of eyelashes and possible permanent erythema of the flap[29]. For defects larger than 50%, Mukit et al[6] propose a technique that reconstructs the anterior lamella with a single or bipedicle myocutaneous Tripier flap from the upper eyelid and the posterior lamella with a chondroperichondral graft from the auricular concha, as already described by Parodi et al[32]. According to Chang et al[8], defects of such dimensions can be reconstructed using a single or bipedicle Tripier flap and a tarsoconjunctival graft harvested from the upper eyelid for the posterior lamella. In our experience, depending on the width of the residual defect in the anterior lamella (and the availability of tissue in the posterior lamella), we propose the Tripier flap or the Tenzel flap for the anterior lamella and a tarsoconjunctival (primarily) or cartilage graft from the auricular concha for the internal lamella. Perry and Allen[29] state that defects larger than 2/3 (but not complete) of the lower eyelid require, in addition to a periosteal flap, a tarsoconjunctival graft to ensure the stability of the posterior lamella.

Defects > 2/3 of the eyelid width: For complete defects of the lower eyelid, the use of a rotation flap from the cheek region (Mustardé flap) is considered necessary by most authors[8,33,34]. According to our algorithm, we suggest the Mustardé flap combined with a tarsoconjunctival or cartilage graft (from the concha) in these cases. For example, Boutros and Zide[34] utilized an oral mucosa graft for the reconstruction of the posterior lamella. Chang et al[8] find the Hughes flap or tarsoconjunctival, mucosal (hard palate or buccal), cartilage (from the nasal septum), or acellular dermal matrix grafts useful when combined with the Mustardé flap for this purpose. Mukit et al[6] propose in these cases the modified Fricke flap “a temporally based forehead transposition flap” as suggested by Barba-Gómez et al[35], for the reconstruction of the anterior lamella combined with a tarsoconjunctival graft and a periosteal flap from the lateral orbital rim for the posterior lamella, as described by Rajabi et al[11]. In the original work, Barba-Gómez et al[35] did not reconstruct the posterior lamella. There is a lack of large studies confronting functional and aesthetic results of the aforementioned reconstructive options.

Medial or internal canthus reconstruction

As suggested by Mukit et al[6] and consistent with our findings, a separate discussion is warranted for the medial canthal region. This area is characterized by minimal excess tissue and very thin subcutaneous tissue, leading to the characteristic central depression. When small excisions are involved, reconstruction may not be necessary, as described in multiple studies. In this area, healing by secondary intention can produce good aesthetic results[36] due to the resistance of the nasal bones to scar contracture, which limits the potential for cicatricial ectropion[8]. In contrast, when abnormalities of the anterior lamella affect the central or lateral regions of the lower eyelid, healing by secondary intention carries a significant risk of cicatricial ectropion. Significant defects necessitate repair utilizing grafts or local flaps. The restricted capacity for skin retraction in this region permits the application of full-thickness skin grafts (such as those obtained from the contralateral top eyelid); nonetheless, the predominant approach employs local flaps, which differ based on the defect’s dimensions[37]. The myocutaneous flap of the upper eyelid is useful because it is thin, excellent in consistency and color, has stable vascularization, and leaves minimal scarring at the donor site. It is often used as a V-Y advancement flap but has the limitation of not being able to cover large defects that extend beyond the medial canthal region and close to the glabella and dorsal nasal wall[38].

The most commonly used alternative for reconstructing this area is the glabellar flap. It is a flap with stable vascularity and a skin texture similar to that of the canthal region; the disadvantage is its thickness, which needs to be reduced to avoid an unaesthetic effect in the recipient area[37,39]. It can be used to repair small to medium-sized defects[40]. In our experience, as described by other authors, thinning the flap ensures a good aesthetic result and maintains the profile of the inner canthus. We have observed temporary lymphatic stasis in the flap, which resolves within 3-6 months, aided by lymphatic drainage massage recommended to the patient. In cases of excisions extending inferiorly to the medial canthus and not reachable by the glabellar flap, we have successfully proposed a V-Y advancement flap from the malar region to complete the reconstruction. The donor area of the glabellar flap can be directly sutured, but when this is not possible or aesthetically concerning, combining a Rintala flap - a frontal based transposition flap- to cover the resulting defect could be an option, as proposed by Onishi et al[41]. If the defect partially extends to the medial extremity of both the upper and lower eyelids, we usually split the distal part of the flap to reconstruct both. Finally, the last solution successfully described in the literature, although with some limitations, is represented by the forehead flap[42]. The Indian flap provides the ability to cover large defects in the periocular and nasal regions and to sculpt a flap according to the shape of the area to be reconstructed. The axial blood supply provides robust nourishment, preventing distal necrosis. Complications are rare with this flap. However, patients must undergo a multi-stage procedure and hematoma can occur.

Complications and limits

From the standpoint of complications, we must consider that, although usually rare, the eyelid region can also be affected. These complications must certainly be avoided, including entropion, ectropion, lagophthalmos, epiphora, and corneal exposure[9]. Infections are relatively rare[43], occurring in less than 1% of cases across nearly all studies in the literature. Prophylactic administration of perioperative antibiotics is unnecessary except when using grafts, while topical antibiotics in the postoperative period are deemed sufficient for preventing infection[44]. Post-surgical hematomas and eyelid edema are very common due to the laxity of the skin in this area; patients should be warned about their possible appearance, as the effect can sometimes be noticeable. The local application of cold dressings (used by us except in cases where a flap has been utilized) can help prevent their subsequent reduction[9].

The most important early complications in eyelid reconstruction are flap necrosis and wound dehiscence. Although very rare, complete necrosis of the flap used in eyelid reconstruction necessitates an urgent surgical reintervention to limit corneal exposure and the risk of damage. Partial necrosis, slightly more common than the former (though there is a lack of review-focused literature solely on complications), typically requires surgical flap revision, with the success of reconstruction dependent on the extent of the necrosis. Wound dehiscence, linked to excessive tension between the opposing tissue portions, is a known event encountered in 2 cases in our experience, consistent with literature reports. When suturing a full-thickness eyelid defect, it is crucial to first perfectly correct the tarsus, optimally approximating the two ends without any misalignment; then, to avoid wound dehiscence, if excessive tension is noted, a lateral canthotomy can be performed to reduce the horizontal component of the tension[8].

During the postoperative period and the subsequent weeks, a prominent concern for a plastic surgeon may arise: Eyelid malposition, which can impact both the upper (less frequently) and lower eyelids, potentially leading to severe instances of entropion or ectropion. Inadequately handled or inaccurately evaluated eyelid malpositions can result in exposure keratitis, corneal ulceration, and, in severe instances, blindness[45]. The likelihood of these problems is greater for upper eyelid anomalies, although they often arise in lower eyelid deficits as well[46]. To avert such repercussions, it is imperative to reconstruct a firm and secure eyelid margin, as this mitigates corneal injury induced by the keratinized eyelid epithelium. Ectropion results in the exposure of the palpebral, bulbar, or corneal conjunctiva, potentially resulting in dry eye and tears, which may lead to long-term consequences such as chronic conjunctivitis, discomfort, or photophobia. To prevent this issue, scars should be oriented vertically or perpendicularly to the free eyelid margin when the size of the tumor allows. In employing a malar flap to repair a lower eyelid defect, the malar incision must ascend diagonally; this facilitates enhanced flap advancement and mitigates ectropion by restricting vertical traction. Consequently, it is imperative to maintain that the generated tension remains consistently horizontal and never vertical[9].

Lagophthalmos is a disorder characterized by the inability to completely close the eyelids, leading to corneal exposure and an increased risk of keratitis or ulceration; it may arise following upper eyelid surgery. To avert this issue, it is essential to preserve a minimum of 1 cm of skin between the superior edge of the excision and the inferior boundary of the eyebrow. Epiphora may occur in cancers involving the lacrimal puncta, requiring their removal. As previously stated, when employing a glabellar flap to rectify medial canthal abnormalities, it is essential to prevent a trapdoor effect or thickening of the flap relative to the eyelid skin to which it is affixed. Constraints about our proposed algorithm encompass limited sample sizes and possible publication biases in existing studies. Subsequent investigations ought to examine long-term results to further refine the algorithm. Future research should evaluate the algorithm across varied populations and examine the impact of novel graft materials on enhancing reconstructive outcomes.