Published online Dec 18, 2024. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v14.i4.97474

Revised: July 31, 2024

Accepted: August 6, 2024

Published online: December 18, 2024

Processing time: 111 Days and 10.5 Hours

Kidney transplantation (KT), although the best treatment option for eligible patients, entails maintaining and adhering to a life-long treatment regimen of medications, lifestyle changes, self-care, and appointments. Many patients experience uncertain outcome trajectories increasing their vulnerability and symptom burden and generating complex care needs. Even when transplants are successful, for some patients the adjustment to life post-transplant can be challenging and psychological difficulties, economic challenges and social isola

Core Tip: Kidney transplant recipients and candidates face several uncertainties in their care journey and have several expressed unmet healthcare needs. We recommend a structured and comprehensive approach to transplant care across the entire continuum of a transplant patient’s journey similar to what has been developed in the field of oncology. The supportive care in transplantation model can operationalize patient-centered care and build on the efforts of other researchers in the field. We postulate that such a model would significantly improve care delivery and patients’ experiences and outcomes and potentially decrease healthcare utilization and cost.

- Citation: Slominska A, Loban K, Kinsella EA, Ho J, Sandal S. Supportive care in transplantation: A patient-centered care model to better support kidney transplant candidates and recipients. World J Transplant 2024; 14(4): 97474

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v14/i4/97474.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v14.i4.97474

Patients with kidney failure benefit from (KT)[1,2], and experience improved survival rates when compared with dialysis[3-6]. KT studies, using validated instruments, have also consistently demonstrated that kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) experience better health-related quality of life and several improvements in other disease-specific domains when compared with dialysis[7]. In countries where dialysis is out of reach for many, the diagnosis of kidney failure would be futile without KT[8]. Thus, increasing KT has been a priority for the nephrology and transplant communities. This priority has been reflected in recent global trends: Of the 79 countries where data were available, the International Society of Nephrology’s Global Kidney Atlas reported that the prevalence of KTRs in 2023 was 279 per million population which represented an increase of 9.4% from the data published four years prior[8].

Despite this growth, KT can be a challenging journey for many patients and it is sometimes regarded as a ‘cure’, which does not conform with the reality that many patients experience[9-13]. KTRs must maintain a life-long treatment regimen of medications, lifestyle changes, self-care and medical appointments[14-17]. As poignantly stated by a young female transplant recipient, “I thought everything would change once I got my kidney. I thought I would be healthy again” but after experiencing multiple side effects of immunosuppressive medications and graft loss, she stated, “I am just a different kind of patient now”[18]. Indeed, a significant proportion of patients experience graft failure and return to dialysis; it is estimated that over 50% return to dialysis within 10 years of KT[19-23]. Patients are often not prepared for this outcome and report several psychosocial and physical ramifications of graft failure[24,25]. Overall, high symptom burden, adverse effects of immunosuppressants, risk of graft rejection or failure and mortality, contribute to complex needs, vulnerability and uncertainties for patients, increasing their care needs and treatment burden[26-30].

In this paper, we highlight the complex journey that KTRs and candidates undertake that can generate varied outcome trajectories and complex healthcare needs. We highlight the need for a comprehensive patient-centered approach to care and conclude with a proposal for a “supportive care in transplantation” care model.

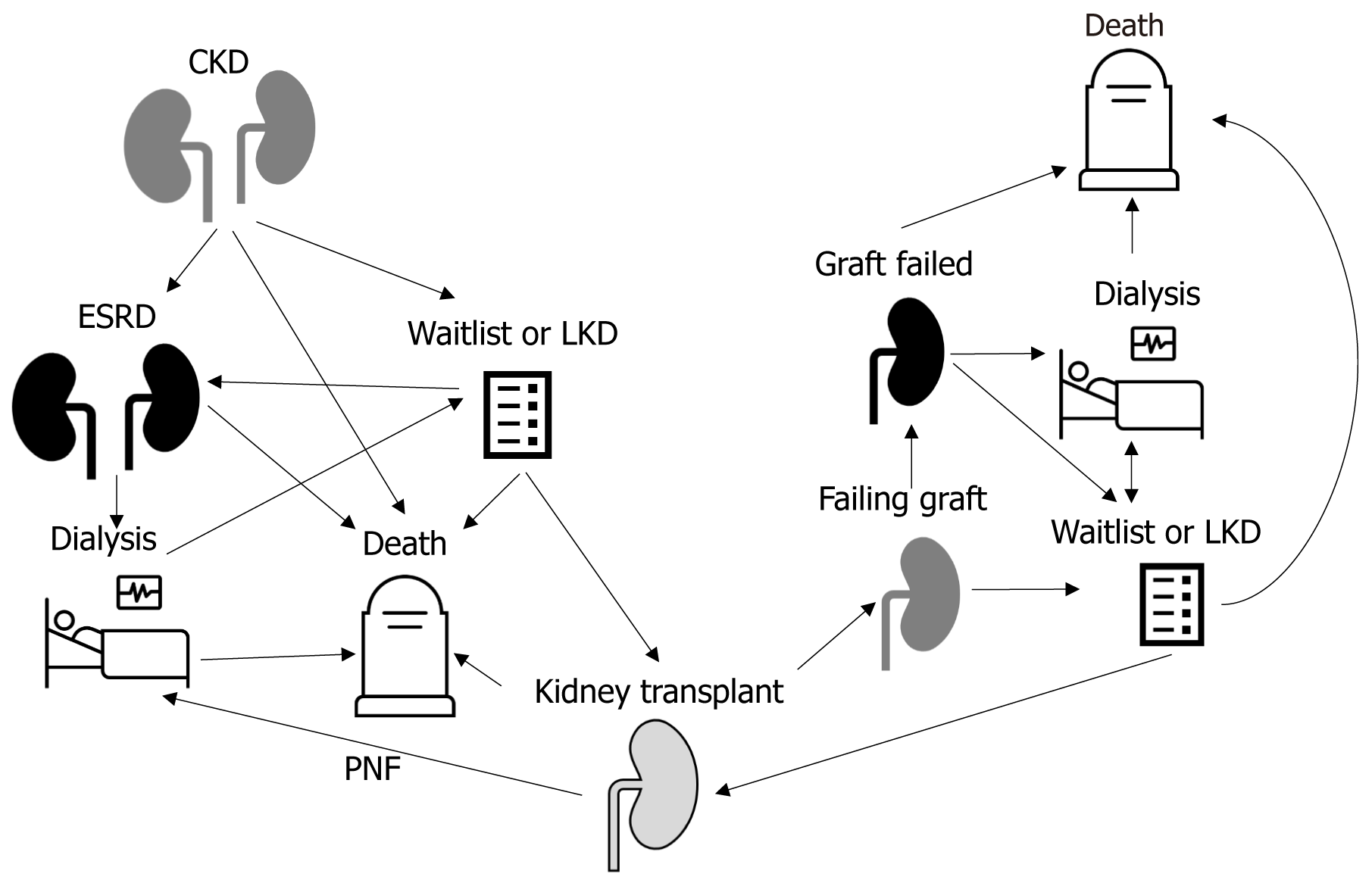

The journey of a kidney failure patient’s pursuit of transplantation is intricate and complex and patients have variable care needs in each phase (Table 1). Patients are at risk of health deterioration, psychosocial vulnerability and increased frailty that may change their clinical course, with the risk of death being present each step of the way (Figure 1).

| Waitlisting to transplantation |

| Transplant eligibility/candidacy |

| Living donor candidacy, if available |

| Support and preparation for various outcomes |

| Death |

| Ineligibility |

| Health deterioration |

| Being re-activated after being inactivated |

| Symptom burden |

| Health maintenance |

| Vaccination and preventative care |

| Kidney transplantation |

| Support and preparation for various outcomes |

| Graft failure |

| Death |

| Rejection |

| Surgical complications |

| Medication management |

| Short and long-term medical complications |

| Short and long-term infectious complications |

| Risk of malignancy |

| Symptom burden |

| Health maintenance |

| Vaccination and preventative care |

| Isolation (no longer on dialysis) |

| Return to workforce |

| Graft failure |

| Support and preparation for various outcomes |

| Death |

| Re-listing and re-transplantation |

| Ineligibility |

| Psychosocial support (patient, caregiver, living donor) |

| Transition of care |

| Immunosuppression plan |

| Medical complications |

| Infectious complications |

| Risk of malignancy |

| Symptom burden |

| Health maintenance |

| Vaccination and preventative care |

Patients with kidney failure undergo a prolonged evaluation to determine whether they are suitable candidates for a transplant and whether a potential living donor candidate would be cleared for donation. Those waitlisted for deceased donation face another period of uncertainty as a transplant is not guaranteed and changes in the medical, surgical, or psychosocial state of the candidate can lead to inactivation, death or ineligibility for a transplant[31,32]. For example, the United States Renal Data System reported that among waitlisted patients, 38.8% were inactivated from the waitlist in 2020[21]. For those waitlisted between 2015-2017 years, 3 years after waitlisting, 5.7% had died and 13.9% had been removed from the waitlist[21]. Data from Australia reveal similar trends and demonstrate that inactivation from the waitlist one time had reduced access to deceased donor KT by about 30% and a 12-fold increase in the risk of death[32]. High prevalence of suboptimal health indicators, such as frailty, have been described and likely contribute to excess mortality[33-35].

After KT, patients need to learn how to integrate medication and lifestyle changes into daily life routines[36-39]. Many are unprepared for the considerable time, effort and cost involved in adhering to their immunosuppressive medications[40]. Also, although the goal is for the patient to receive a transplant and return to an improved state of health, this does not translate into a straightforward and predictable trajectory for all recipients. A small proportion experience primary-nonfunction and return to dialysis immediately[41]. For others, the experience contains other uncertain trajectories, including suboptimal graft function, symptom burden, adverse effects of immunosuppressive medications, and the possibility of rejection. Other possibilities include surgical complications[42,43], increased risks of infections and mali

Even when transplants are successful, the adjustment to life post-transplant can be challenging and adaptation can be accompanied by negative emotions like guilt, sadness and anger[50,51]. A systematic review identified 23 studies where KTRs described psychological difficulties, including anxiety or depression in response to uncertainty about the future as well social difficulties due to minimizing contact with others for infection risk reasons and economic challenges due to the costs of medications[52].

Despite several advances in diagnostics and therapeutics, 2%-5% of patients experience graft failure annually and it is becoming a leading cause of patients needing dialysis[21]. Management of patients with graft failure is complex and costly and outcomes are worse than in transplant naïve patients with kidney failure[26-30]. In a recent prospective cohort study of 16 Canadian centres, where 269 KTRs were enrolled within 21 days of graft failure, the unadjusted death rate was 7.51 per 100 patient-years and the overall hospitalization rate was 93.7 per 100 patient-years[53]. Uncertainties regarding the medical and surgical care of these patients may contribute to poor outcomes[54-58], as may practices with respect to immunosuppression management[53,59,60]. Graft failure can have medical and psychological consequences across several life domains and was the subject of a recent controversies conference from a leading global organization[24]. Patients with graft failure are faced with the need to return to dialysis, uncertain prospects of re-transplantation, and possibly end-of-life decisions.

There is minimal understanding of the needs of preparing and supporting KTRs for potential outcome of death even though it is an outcome experienced by many along the transplant journey (Figure 1). Care teams may themselves lack the necessary expertise or resources to support patients and report difficulties in engaging in these conversations[61]. Integration of palliative and supportive care is needed as robust data from the oncology and non-cancer literature suggest that early palliative care leads to longer survival, lower symptom burden, improved quality of life and improved patient understanding of prognosis[62-64]. Also, in patients dying from non-cancer illness related to chronic organ failure, a study from Canada demonstrated that palliative care was associated with significantly lower healthcare use[65]. Yet, palliative care access among solid organ transplant recipients with a terminal diagnosis is much lower than those with a cancer diagnosis and referral to palliative care usually occurs much later in their disease trajectory[66].

Given the challenges described above, it is apparent that KTRs require more support and preparation for various outcomes than is currently provided. The centrality of the patient to all initiatives has been highlighted[67], and improving patient-centered care in transplantation has gained momentum[68-72]. Patient-centred care is an approach rooted in a deep respect for patients as unique individuals and entails being responsive to patient and families’ needs, beliefs and preferences[73-75]. It puts patients at the forefront of their health and care by engaging them in evidence-informed shared decision-making and supporting a partnership between individuals, families, and health care services professionals[76-78]. Significant attention has recently been devoted to operationalizing patient-centered care and devising pathways from targeted patient-centered care efforts to enhanced patient outcomes, and transplant care is no exception[79-83]. We elaborate on some initiatives that are aiming to better describe care gaps and understand care needs that can help advance patient-centered care in transplantation.

The standardized outcomes in nephrology-transplantation initiative developed a core set of outcome domains for trials in transplantation[84,85]. Six were identified as critically important to all stakeholders: Graft health, mortality, car

A 2023 kidney disease–improving global outcomes controversies conference identified a broad set of needs in tran

A transplant-specific measure of treatment burden that can improve patient-centered care is being proposed as an exploratory endpoint[14]. Other studies have examined interventions toward self-management, particularly in the young adult cohorts[87]. Self-management is defined as “the tasks that individuals must undertake to live with one or more chronic conditions”[88]. Overall, however, self-management interventions tend to focus on the medical challenges and not on the emotional and social challenges of KTRs[36,38]. Two nurse-led self-management interventions have shown promising results as KTRs became aware of the challenges they faced and the progress they made during the intervention[36,87].

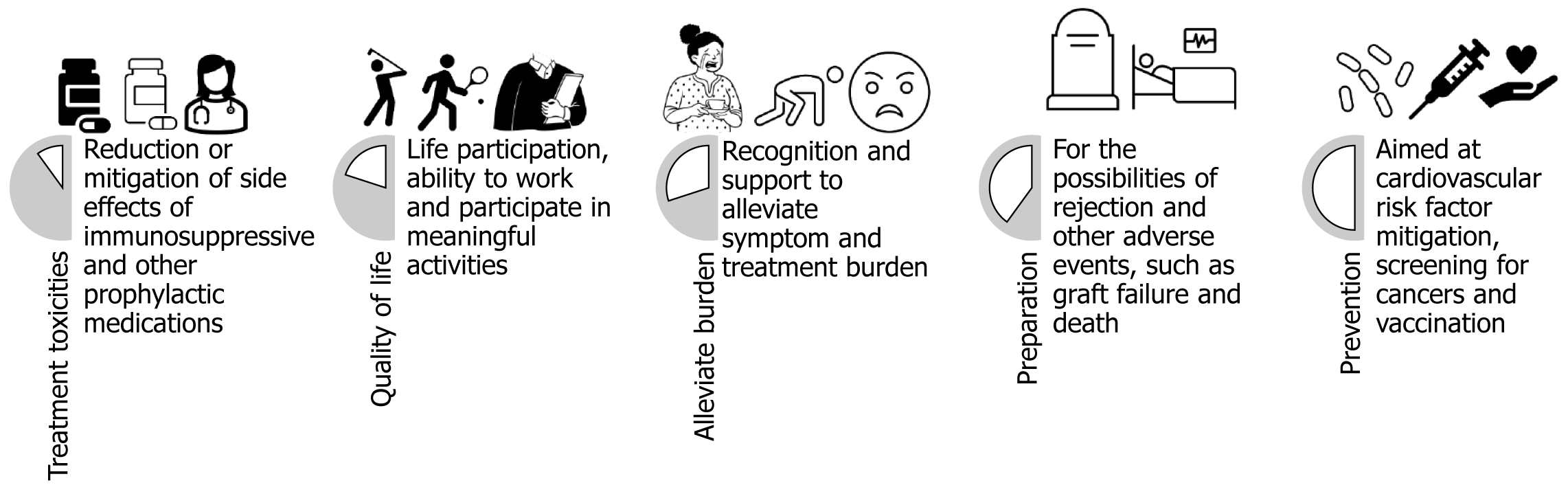

Drawing upon these initiatives, we have identified five expressed healthcare needs of KTRs that are largely unmet in clinical care (See Figure 2). Advancing patient-centered care will entail addressing these unmet needs and identifying other emerging and unexpressed needs. Healthcare needs have been defined in the quality of life literature as “what patients desire to receive from healthcare services to improve overall health”[89]. Unmet needs are those that are not optimally met either due to unexpressed demand or expressed demand that is sub-optimally met[90].

While the above-mentioned initiatives are a significant achievement in advancing a patient-centered approach in transplantation, how to operationalize this approach is currently limited or isolated to one phase or one outcome trajectory. Thus, we propose an integrated framework which we call “supportive care in transplantation” that builds on the philosophical foundations developed in the oncology literature.

Supportive care in oncology or supportive oncology was a movement that gained momentum in the late 20th century, as the focus on improving a patient’s quality of life and managing symptoms and side effects of cancers and their therapies gained importance[91]. It has been defined as “care which helps the individual and his/her family deal with the experience of cancer”[92,93] including coping with the disease and treatment[94]. It involves a coordinated, person-centric, holistic approach to patient care. In oncology, supportive care is now an established paradigm, supported by the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer[95]. Founded in 1990, this is an international, interdisciplinary organization dedicated to the practice, education, and research of supportive care in cancer[96].

While initially focusing on palliative care that emphasized pain management, psychological well-being, and end-of-life care, it now encompasses strategies that include the management of physical and psychological symptoms and improving the quality of rehabilitation, secondary cancer prevention, and survivorship[92]. The concept breaks from an older model of oncology structured around two opposing poles: Curative treatment and life-prolonging therapies on the one end and end-of-life on the other[97]. It acknowledges that the contemporary cancer experience is more of a continuum and a chronic condition where patients have ongoing needs for the prevention and management of sym

We propose a similar approach to care in the field of KT. This model can help advance patient-centered care in transplantation, support KTRs through uncertain trajectories (Figure 1), address the previously identified unmet care needs (Figure 2), help conceptualize the aspects of support KTRs might require and create opportunities to generate evidence that can then inform clinical practice. We present some of our preliminary work in developing this care model and highlight that ongoing work in our research group will further illuminate its elements, framework and imple

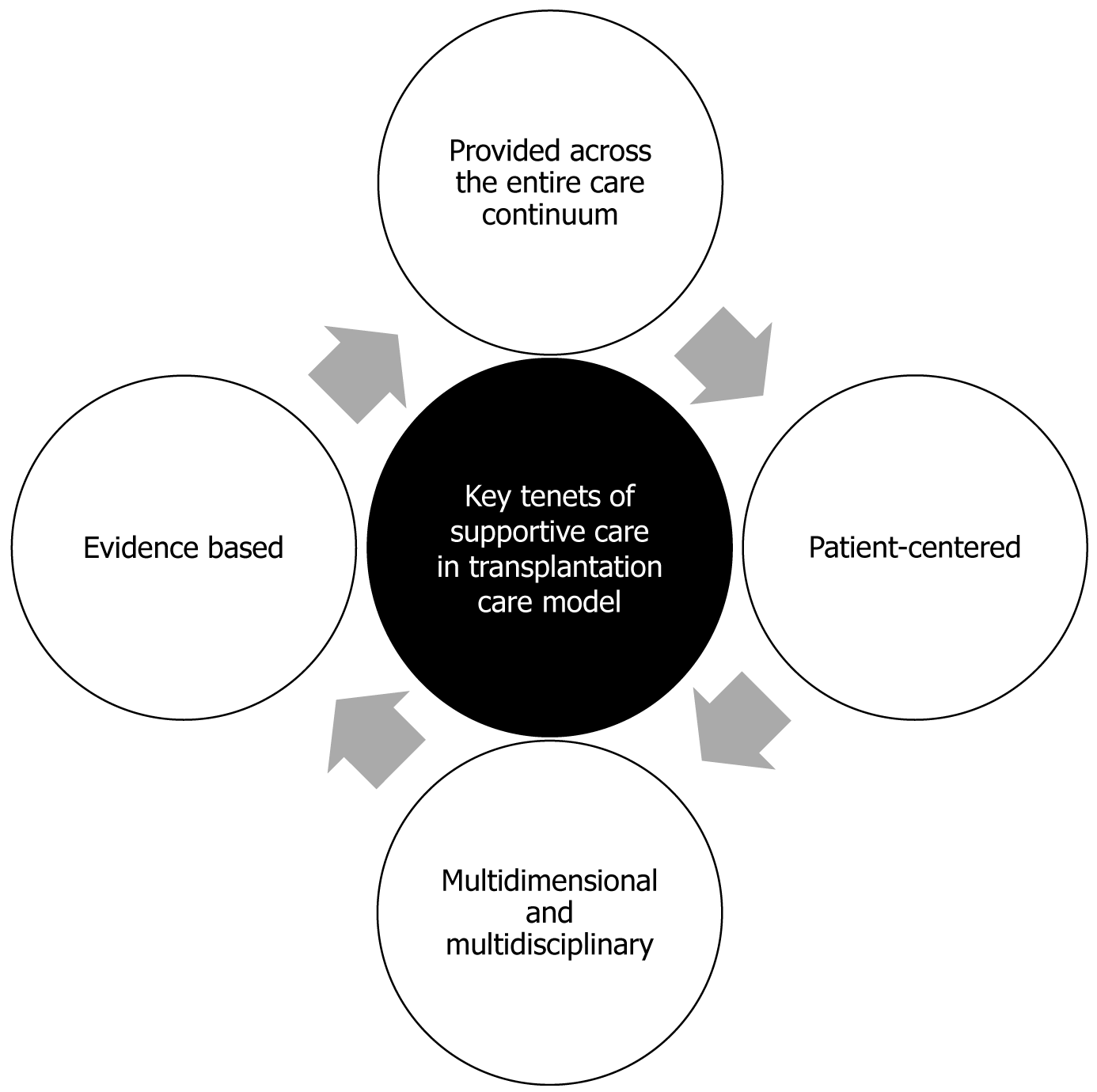

Supportive care has been identified as a core component of integrated kidney care in the general nephrology literature[98]; however a structured and comprehensive care model for how to deliver it is currently lacking. The oncologic literature highlights that the ideal model of supportive oncology does not exist yet[99]. Concerns related to supportive care being a patchwork of different medical specialties have been raised as well[100]. The European Society of Medical Oncology has identified some key features of supportive care[94]. We draw on these, as well as the literature on patient-centered care[70-73,101] to propose four key tenets of supportive care in transplantation (Figure 3).

Patient-centered care is one where patients are partners with their health care providers and “an individual’s specific health needs and desired health outcomes are the driving force behind all health care decisions and quality measurements”[102]. The Picker Principles of patient-centered care comprehensively capture eight aspects of care which we contend are well suited to inform the first tenet of supportive care in transplantation model[70-73]. This model was developed by researchers from Harvard Medical School on behalf of the Picker Institute (https: //picker.org/) and the Commonwealth Fund and has been adopted by the National Academy of Medicine for achieving patient-centeredness, a key aim to transform the United States healthcare system[103]. The eight principles are: (1) Respect for patients' values, preferences and expressed needs; (2) Coordination and integration of care; (3) Information and education; (4) Physical comfort; (5) Emotional support and alleviation of fear and anxiety; (6) Involvement of family and friends; (7) Continuity and transition; and (8) Access to care. We believe that the incorporation of these principles as the first tenet of supportive care in transplantation can help to counter several problems identified in supportive oncology, such as challenges with coordination, communication and continuity of care[104].

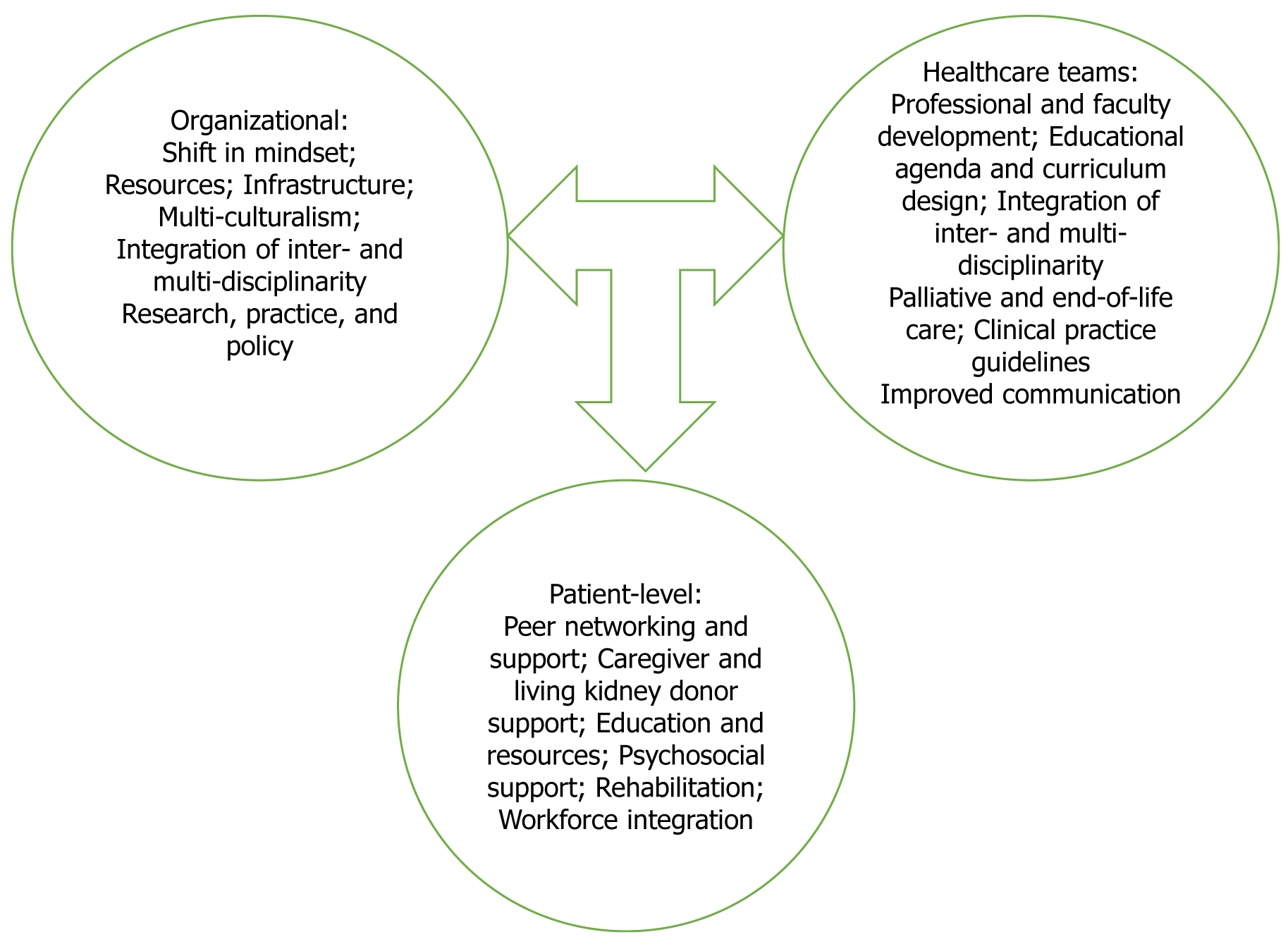

According to Krishnasamy et al[105] and Fitch et al[106] seminal text in supportive oncology, there are several domains of supportive care: Informational, emotional, practical, physical, psychological, social and spiritual. A multidimensional approach can support the formulation of an individual's health problem from a biological, psychological or social perspective[107]. Multidisciplinary care can bring together healthcare professionals from different fields to better inform a patient’s diagnostic and therapeutic plan[108]. These approaches can improve patient care and maximize the quality of patient outcomes[109]. The paradigm of supportive care also conceptualizes the role of the oncologist as not only delivering “the best quality anticancer treatment” but also taking into account “the impact of the disease and treatment on each patient’s life”[94]. Additionally, with this approach, the oncologist includes and collaborates with other healthcare providers in order to address the full spectrum of patients’ needs[104]. We highlight generative components and strategies for different levels of the health system and the benefit of inter- and multi-disciplinary approaches (Figure 4). While transplant teams may continue to play a central role, this care model calls for a coordinated and integrated approach that involves a range of other healthcare professions and disciplines, such as palliative care, primary care, social work, rehabilitation, nutritional support, psychiatric services, psychological and spiritual counselling and integrative medicine.

As highlighted above, the journey of a KTRs is complex and does not end with the transplant surgery. Patients require significant support to manage their care especially when they experience uncertain trajectories, such as infections and glomerulonephritis recurrence or as they experience graft failure and return to dialysis. A third key tenet of supportive care is to provide care across the entire transplant journey. Of note, supportive care tends to be associated with palliative care[110]. Indeed, even in cancer care the term supportive care has been replaced by supportive oncology[104]. We highlight that the crux of supportive care is a person-centered approach that recognizes the “totality of experience”[106], and that palliative care is a part of supportive care in the KT context.

Evidence-based practice is defined as the “conscientious and judicious use of current best evidence in conjunction with clinical expertise and patient values to guide health care decisions”[111]. While ideally generated from randomized controlled trials, this can be difficult to achieve in transplantation. Thus, other scientific methods such as descriptive and qualitative research, case reports, scientific principles, and expert opinion are also necessary to inform care; as the research accumulates the best available evidence will need to be incorporated[111,112]. However, we highlight that advancing supportive care in practice can lead to advances in evidence creation. For example, in oncology, chemo

| For the patient and families |

| Improve quality of life |

| Decrease symptom burden |

| Facilitate self-management |

| Improve adherence |

| Decrease risk of graft loss |

| Decrease risk of mortality |

| Improve end-of-life care delivery |

| Among patients with graft failure |

| Facilitate transitions of care |

| Improve outcomes |

| Facilitate re-transplantation |

| Decrease caregiver burden |

| For public health and healthcare |

| Decrease healthcare utilization |

| Reduce emergency visits |

| Minimize need for hospitalizations |

| Increase patient return to workforce |

| Maximize organ utility |

| Social return on investment |

| Improve collaborations between care teams |

| For research progress |

| Identify research priorities |

| Create collaborative networks |

| Opportunities for patient partnerships |

| Improve feasibility of trials |

Preventative, supportive, and early approaches are generally known to decrease healthcare costs and improve patient outcomes. While there have been few formal assessments of supportive oncology, there is growing evidence that interventions to manage the specific problems encountered within supportive care lead to improved symptom control and quality of life[104,114], as well as reduced emergency visits and hospital admissions[115-118]. For example, the integration of electronic patient-reported outcomes into routine oncology practice for symptom monitoring in patients with metastatic cancer was associated with increased survival compared with usual care[119]. In an ambulatory setting, unmet supportive care needs were associated with a 45% higher risk of emergency room visits and a 36% higher risk of hospitalizations[118]. In another study, a dedicated supportive care service led to a 3.2% decrease in unplanned hospital admissions, a 5% decrease in emergency room visits and a 2.2% decrease in costs related to hospitalizations[117]. In an economic analysis, a return on investment with a benefit-cost ratio of 1.4 was demonstrated[115]. Furthermore, there are potential survival benefits if, as a result of supportive care, better adherence to treatment regimens is achieved. Minimizing adverse effects enables maximum benefit from treatment. Better symptom management can lead to increased life and workforce participation, thus, proponents argue that supportive care also offers a social return on investment[104].

We propose that similar benefits can be observed in KTRs; supportive care in transplantation can improve quality of life, ability to work, and treatment adherence. Non-adherence is a major reason for graft loss, particularly among adolescent and young adult KTRs[120-124]. In addition, the care of KTRs is costly and in the United States, inflation-adjusted per-person per-year expenditures for medicare fee-for-service was $43913 in 2021[21]. This is variable and is dictated by the outcome trajectories as some patients with more complications and fewer supports likely access tertiary care or emergency services more than others. The coronavirus disease pandemic has also highlighted the disproportionate burden of healthcare utilization by transplant recipients and supportive care model can minimize utilization of tertiary services and decrease healthcare costs[21].

Lastly, a transplant is a gift to society, the patient and the healthcare system from the deceased donor or the living kidney donor. The ethical principle of utility dictates maximizing the expected net amount of overall good[125]. Prolonging the survival of the graft and the patient is key to this ethical principle. Thus, we believe that a social return on investment of this supportive model of care in KT will be worth the initial investment and costs (Table 2).

KTRs and candidates face several uncertainties in their care journey and have several expressed unmet healthcare needs. We recommend a structured and comprehensive approach to transplant care across the entire continuum of a transplant patient’s journey similar to what has been developed in the field of oncology. The supportive care in transplantation model can operationalize patient-centered care and build on the efforts of other researchers in the field. We postulate that such a model would significantly improve care delivery and patients’ experiences and outcomes and potentially decrease healthcare utilization and cost.

| 1. | Sandal S, Ahn JB, Chen Y, Massie AB, Clark-Cutaia MN, Wu W, Cantarovich M, Segev DL, McAdams-DeMarco MA. Trends in the survival benefit of repeat kidney transplantation over the past 3 decades. Am J Transplant. 2023;23:666-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sandal S, Ahn JB, Segev DL, Cantarovich M, McAdams-DeMarco MA. Comparing outcomes of third and fourth kidney transplantation in older and younger patients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:4023-4031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim SJ, Klarenbach S, Lafrance J-P, Hospital M-R, Moist L, Sood MM, Zhu N, Samuel SM, Kappel J, Ivis F, Lam K, Redding N, Terner M, Webster G, Wu J. High Risk and High Cost: Focus on Opportunities to Reduce Hospitalizations of Dialysis Patients in Canada. CIHI Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2016. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/report-corr-high-risk-high-cost-en-web.pdf.. |

| 4. | Barnieh L, King-Shier K, Hemmelgarn B, Laupacis A, Manns L, Manns B. Views of Canadian patients on or nearing dialysis and their caregivers: a thematic analysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2014;1:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1725-1730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3684] [Cited by in RCA: 3856] [Article Influence: 148.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, Bello A, Browne S, Jadhav D, Klarenbach S, Gill J. Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2093-2109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 896] [Cited by in RCA: 1045] [Article Influence: 74.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang Y, Hemmelder MH, Bos WJW, Snoep JD, de Vries APJ, Dekker FW, Meuleman Y. Mapping health-related quality of life after kidney transplantation by group comparisons: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021;36:2327-2339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bello A, Okpechi I, Levin A, ISN–Global Kidney Health Atlas. A report by the International Society of Nephrology: An Assessment of Global Kidney Health Care Status focussing on Capacity, Availability, Accessibility. Affordability and Outcomes of Kidney Disease. ISN. 2023;. |

| 9. | Kierans C. Narrating kidney disease: the significance of sensation and time in the emplotment of patient experience. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2005;29:341-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jamieson NJ, Hanson CS, Josephson MA, Gordon EJ, Craig JC, Halleck F, Budde K, Tong A. Motivations, Challenges, and Attitudes to Self-management in Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67:461-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mappin-Kasirer B, Hoffman L, Sandal S. New-onset Psychosis in an Immunosuppressed Patient With Kidney Transplantation: An Educational Case Report. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7:2054358120947210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cherniak V, Demir KK, Sandal S, Cantarovich M, Podymow T, Naessens V, Ponette V, Wou K, Do AT, Malhamé I. Thrombotic Microangiopathy in a Pregnant Woman With Kidney Transplantation: A Case Report. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2021;43:874-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Robert JT, Rajaram A, Fiset PO, Bernard C, Samanta R, Sandal S. Class V lupus nephritis recurrence with histologic resolution in a kidney transplant recipient on a pregnancy-adapted immunosuppression protocol: a lesson for the clinical nephrologist. J Nephrol. 2024;37:811-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lorenz EC, Egginton JS, Stegall MD, Cheville AL, Heilman RL, Nair SS, Mai ML, Eton DT. Patient experience after kidney transplant: a conceptual framework of treatment burden. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2019;3:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tucker EL, Smith AR, Daskin MS, Schapiro H, Cottrell SM, Gendron ES, Hill-Callahan P, Leichtman AB, Merion RM, Gill SJ, Maass KL. Life and expectations post-kidney transplant: a qualitative analysis of patient responses. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ogunbayo OJ, Schafheutle EI, Cutts C, Noyce PR. Self-care of long-term conditions: patients' perspectives and their (limited) use of community pharmacies. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39:433-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sandal S, Chen T, Cantarovich M. Evaluation of Transplant Candidates With a History of Nonadherence: An Opinion Piece. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021;8:2054358121990137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Scott KW, Hollingsworth GM. Perceptions of a multiple kidney transplant recipient: understanding a fragile life. Nephrol Nurs J. 2010;37:161-166. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Marcén R, Teruel JL. Patient outcomes after kidney allograft loss. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2008;22:62-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ojo A, Wolfe RA, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK, Leavey SF, Callard SE, Dickinson DM, Schmouder RL, Leichtman AB. Prognosis after primary renal transplant failure and the beneficial effects of repeat transplantation: multivariate analyses from the United States Renal Data System. Transplantation. 1998;66:1651-1659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | United States Renal Data System. 2022 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. 2022. Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/search?s=all&q=2022+USRDS+Annual+Data+Report%3A+Epidemiology+of+kidney+disease+in+the+United+States. |

| 22. | Hariharan S, Israni AK, Danovitch G. Long-Term Survival after Kidney Transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:729-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 92.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Davis S, Mohan S. Managing Patients with Failing Kidney Allograft: Many Questions Remain. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17:444-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Josephson MA, Becker Y, Budde K, Kasiske BL, Kiberd BA, Loupy A, Małyszko J, Mannon RB, Tönshoff B, Cheung M, Jadoul M, Winkelmayer WC, Zeier M; for Conference Participants. Challenges in the management of the kidney allograft: from decline to failure: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2023;104:1076-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Loban K, Horton A, Robert JT, Hales L, Parajuli S, McAdams-DeMarco M, Sandal S. Perspectives and experiences of kidney transplant recipients with graft failure: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2023;37:100761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lea-Henry T, Chacko B. Management considerations in the failing renal allograft. Nephrology (Carlton). 2018;23:12-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Perl J, Zhang J, Gillespie B, Wikström B, Fort J, Hasegawa T, Fuller DS, Pisoni RL, Robinson BM, Tentori F. Reduced survival and quality of life following return to dialysis after transplant failure: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:4464-4472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rao PS, Schaubel DE, Jia X, Li S, Port FK, Saran R. Survival on dialysis post-kidney transplant failure: results from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:294-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Brar A, Markell M, Stefanov DG, Timpo E, Jindal RM, Nee R, Sumrani N, John D, Tedla F, Salifu MO. Mortality after Renal Allograft Failure and Return to Dialysis. Am J Nephrol. 2017;45:180-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gill JS, Rose C, Pereira BJ, Tonelli M. The importance of transitions between dialysis and transplantation in the care of end-stage renal disease patients. Kidney Int. 2007;71:442-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lee S, Yoo KD, An JN, Oh YK, Lim CS, Kim YS, Lee JP. Factors affecting mortality during the waiting time for kidney transplantation: A nationwide population-based cohort study using the Korean Network for Organ Sharing (KONOS) database. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | De La Mata NL, Khou V, Hedley JA, Kelly PJ, Morton RL, Wyburn K, Webster AC. Journey to kidney transplantation: patient dynamics, suspensions, transplantation and deaths in the Australian kidney transplant waitlist. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2024;39:1138-1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hernández D, Castro-de la Nuez P, Muriel A, Ruiz-Esteban P, Alonso M. Mortality on a renal transplantation waiting list. Nefrologia. 2015;35:18-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pérez-Sáez MJ, Redondo-Pachón D, Arias-Cabrales CE, Faura A, Bach A, Buxeda A, Burballa C, Junyent E, Crespo M, Marco E, Rodríguez-Mañas L, Pascual J. Outcomes of Frail Patients While Waiting for Kidney Transplantation: Differences between Physical Frailty Phenotype and FRAIL Scale. J Clin Med. 2022;11:672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | McAdams-DeMarco MA, Thind AK, Nixon AC, Woywodt A. Frailty assessment as part of transplant listing: yes, no or maybe? Clin Kidney J. 2023;16:809-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Been-Dahmen JMJ, Grijpma JW, Ista E, Dwarswaard J, Maasdam L, Weimar W, Van Staa A, Massey EK. Self-management challenges and support needs among kidney transplant recipients: A qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:2393-2405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nielsen C, Clemensen J, Bistrup C, Agerskov H. Balancing everyday life-Patients' experiences before, during and four months after kidney transplantation. Nurs Open. 2019;6:443-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Schmid-Mohler G, Schäfer-Keller P, Frei A, Fehr T, Spirig R. A mixed-method study to explore patients' perspective of self-management tasks in the early phase after kidney transplant. Prog Transplant. 2014;24:8-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Urstad KH, Wahl AK, Andersen MH, Øyen O, Fagermoen MS. Renal recipients' educational experiences in the early post-operative phase--a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26:635-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Crawford K, Low JK, Manias E, Williams A. Healthcare professionals can assist patients with managing post-kidney transplant expectations. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13:1204-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hamed MO, Chen Y, Pasea L, Watson CJ, Torpey N, Bradley JA, Pettigrew G, Saeb-Parsy K. Early graft loss after kidney transplantation: risk factors and consequences. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:1632-1643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Reyna-Sepúlveda F, Ponce-Escobedo A, Guevara-Charles A, Escobedo-Villarreal M, Pérez-Rodríguez E, Muñoz-Maldonado G, Hernández-Guedea M. Outcomes and Surgical Complications in Kidney Transplantation. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2017;8:78-84. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Humar A, Matas AJ. Surgical complications after kidney transplantation. Semin Dial. 2005;18:505-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Alangaden GJ, Thyagarajan R, Gruber SA, Morawski K, Garnick J, El-Amm JM, West MS, Sillix DH, Chandrasekar PH, Haririan A. Infectious complications after kidney transplantation: current epidemiology and associated risk factors. Clin Transplant. 2006;20:401-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Agrawal A, Ison MG, Danziger-Isakov L. Long-Term Infectious Complications of Kidney Transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17:286-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Ojo AO. Cardiovascular complications after renal transplantation and their prevention. Transplantation. 2006;82:603-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Sandal S, Bae S, McAdams-DeMarco M, Massie AB, Lentine KL, Cantarovich M, Segev DL. Induction immunosuppression agents as risk factors for incident cardiovascular events and mortality after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:1150-1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Gill P, Lowes L. Renal transplant failure and disenfranchised grief: participants' experiences in the first year post-graft failure--a qualitative longitudinal study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51:1271-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Ghadami A, Memarian R, Mohamadi E, Abdoli S. Patients' experiences from their received education about the process of kidney transplant: A qualitative study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2012;17:S157-S164. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Schipper K, Abma TA, Koops C, Bakker I, Sanderman R, Schroevers MJ. Sweet and sour after renal transplantation: a qualitative study about the positive and negative consequences of renal transplantation. Br J Health Psychol. 2014;19:580-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Amerena P, Wallace P. Psychological experiences of renal transplant patients: A qualitative analysis. Couns Psychother Res. 2009;9:273-279. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Yang FC, Chen HM, Huang CM, Hsieh PL, Wang SS, Chen CM. The Difficulties and Needs of Organ Transplant Recipients during Postoperative Care at Home: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Knoll G, Campbell P, Chassé M, Fergusson D, Ramsay T, Karnabi P, Perl J, House AA, Kim J, Johnston O, Mainra R, Houde I, Baran D, Treleaven DJ, Senecal L, Tibbles LA, Hébert MJ, White C, Karpinski M, Gill JS. Immunosuppressant Medication Use in Patients with Kidney Allograft Failure: A Prospective Multicenter Canadian Cohort Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33:1182-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Bakr MA, Denewar AA, Abbas MH. Challenges for Renal Retransplant: An Overview. Exp Clin Transplant. 2016;14:21-26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 55. | Bissonnette J, Woodend K, Davies B, Stacey D, Knoll GA. Evaluation of a collaborative chronic care approach to improve outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2013;27:232-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Fiorentino M, Gallo P, Giliberti M, Colucci V, Schena A, Stallone G, Gesualdo L, Castellano G. Management of patients with a failed kidney transplant: what should we do? Clin Kidney J. 2021;14:98-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Lubetzky M, Tantisattamo E, Molnar MZ, Lentine KL, Basu A, Parsons RF, Woodside KJ, Pavlakis M, Blosser CD, Singh N, Concepcion BP, Adey D, Gupta G, Faravardeh A, Kraus E, Ong S, Riella LV, Friedewald J, Wiseman A, Aala A, Dadhania DM, Alhamad T. The failing kidney allograft: A review and recommendations for the care and management of a complex group of patients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:2937-2949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Alhamad T, Lubetzky M, Lentine KL, Edusei E, Parsons R, Pavlakis M, Woodside KJ, Adey D, Blosser CD, Concepcion BP, Friedewald J, Wiseman A, Singh N, Chang SH, Gupta G, Molnar MZ, Basu A, Kraus E, Ong S, Faravardeh A, Tantisattamo E, Riella L, Rice J, Dadhania DM. Kidney recipients with allograft failure, transition of kidney care (KRAFT): A survey of contemporary practices of transplant providers. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:3034-3042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Pham PT, Everly M, Faravardeh A, Pham PC. Management of patients with a failed kidney transplant: Dialysis reinitiation, immunosuppression weaning, and transplantectomy. World J Nephrol. 2015;4:148-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 60. | Slominska A, Gaudio K, Shamseddin K, Lam N, Ho J, Vinson A, Mainra R, Hoar S, Fortin M, Kim J, DeSerres S, Prasad G, Weir M, Cantarovich M, Sandal S. An environmental scan of Canadian kidney transplant programs for the management of patients with graft failure: A research letter. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2024;. |

| 61. | Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4817] [Cited by in RCA: 5009] [Article Influence: 333.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, Gallagher ER, Jackson VA, Lynch TJ, Lennes IT, Dahlin CM, Pirl WF. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319-2326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 448] [Cited by in RCA: 510] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, Hull JG, Li Z, Tosteson TD, Byock IR, Ahles TA. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1256] [Cited by in RCA: 1324] [Article Influence: 82.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, Dionne-Odom JN, Ernecoff NC, Hanmer J, Hoydich ZP, Ikejiani DZ, Klein-Fedyshin M, Zimmermann C, Morton SC, Arnold RM, Heller L, Schenker Y. Association Between Palliative Care and Patient and Caregiver Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:2104-2114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 870] [Cited by in RCA: 781] [Article Influence: 86.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Quinn KL, Stukel T, Stall NM, Huang A, Isenberg S, Tanuseputro P, Goldman R, Cram P, Kavalieratos D, Detsky AS, Bell CM. Association between palliative care and healthcare outcomes among adults with terminal non-cancer illness: population based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2020;370:m2257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Wentlandt K, Weiss A, O'Connor E, Kaya E. Palliative and end of life care in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:3008-3019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Slominska A, Kinsella EA, Sandal S. Shifting the focus from managing the failing kidney allograft to supporting the patient with a failing kidney allograft. Kidney Int. 2023;104:1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:100-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 923] [Cited by in RCA: 1086] [Article Influence: 77.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J, Delbanco TL. Through the patient's eyes: understanding and promoting patient-centered care. United States: John Wiley and Sons, 2002. |

| 70. | Person- and Family-Centred Care. Toronto, ON: Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario: Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, 2015. |

| 71. | Ortiz MR. Patient-Centered Care: Nursing Knowledge and Policy. Nurs Sci Q. 2018;31:291-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Frampton S, Guastello S, Brady C, Hale M, Horowitz SM, Smith SB, Stone S. Patient-centered care: improvement guide, 2008. |

| 73. | Coulter A. Patient engagement--what works? J Ambul Care Manage. 2012;35:80-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e001570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1284] [Cited by in RCA: 1409] [Article Influence: 117.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Law S, Antonacci R, Ormel I, Hidalgo M, Ma J, Dyachenko A, Laframboise D, Doucette E. Engaging patients, families and professionals at the bedside using whiteboards. J Interprof Care. 2023;37:400-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:780-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2000] [Cited by in RCA: 2225] [Article Influence: 171.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Weston WW. Informed and shared decision-making: the crux of patient-centered care. CMAJ. 2001;165:438-439. [PubMed] |

| 78. | Légaré F, Stacey D, Gagnon S, Dunn S, Pluye P, Frosch D, Kryworuchko J, Elwyn G, Gagnon MP, Graham ID. Validating a conceptual model for an inter-professional approach to shared decision making: a mixed methods study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17:554-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Street RL Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:295-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1316] [Cited by in RCA: 1453] [Article Influence: 90.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Härter M, van der Weijden T, Elwyn G. Policy and practice developments in the implementation of shared decision making: an international perspective. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2011;105:229-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Dilar C, Joana S, Jéssica O. Applying Person-Centered Care Model in the Postoperative Period of Renal Transplant Recipients: A Comprehensive Nursing Approach. In: Associate Prof. Nabil AS, editor. New Insights in Perioperative Care. Rijeka: IntechOpen, 2024. |

| 82. | Dobrijevic E, Scholes-Robertson N, Guha C, Howell M, Jauré A, Wong G, van Zwieten A. Patient-Centered Research and Outcomes in Cancer and Kidney Transplantation. Semin Nephrol. 2024;44:151499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Loban K, Milland T, Hales L, Lam NN, Dipchand C, Sandal S. Understanding the Healthcare Needs of Living Kidney Donors Using the Picker Principles of Patient-centered Care: A Scoping Review. Transplantation. 2024;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Tong A, Gill J, Budde K, Marson L, Reese PP, Rosenbloom D, Rostaing L, Wong G, Josephson MA, Pruett TL, Warrens AN, Craig JC, Sautenet B, Evangelidis N, Ralph AF, Hanson CS, Shen JI, Howard K, Meyer K, Perrone RD, Weiner DE, Fung S, Ma MKM, Rose C, Ryan J, Chen LX, Howell M, Larkins N, Kim S, Thangaraju S, Ju A, Chapman JR; SONG-Tx Investigators. Toward Establishing Core Outcome Domains For Trials in Kidney Transplantation: Report of the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Kidney Transplantation Consensus Workshops. Transplantation. 2017;101:1887-1896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Tong A, Oberbauer R, Bellini MI, Budde K, Caskey FJ, Dobbels F, Pengel L, Rostaing L, Schneeberger S, Naesens M. Patient-Reported Outcomes as Endpoints in Clinical Trials of Kidney Transplantation Interventions. Transpl Int. 2022;35:10134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Jaure A, Vastani RT, Teixeira-Pinto A, Ju A, Craig JC, Viecelli AK, Scholes-Robertson N, Josephson MA, Ahn C, Butt Z, Caskey FJ, Dobbels F, Fowler K, Jowsey-Gregoire S, Jha V, Tan JC, Sautenet B, Howell M. Validation of a Core Patient-Reported Outcome Measure for Life Participation in Kidney Transplant Recipients: the SONG Life Participation Instrument. Kidney Int Rep. 2024;9:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Been-Dahmen JMJ, Beck DK, Peeters MAC, van der Stege H, Tielen M, van Buren MC, Ista E, van Staa A, Massey EK. Evaluating the feasibility of a nurse-led self-management support intervention for kidney transplant recipients: a pilot study. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Crossing the Quality Chasm: Next Steps Toward a New Health Care System. The 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit: A Focus on Communities. Adams K, Greiner AC, Corrigan JM, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004. |

| 89. | Asadi-Lari M, Tamburini M, Gray D. Patients' needs, satisfaction, and health related quality of life: towards a comprehensive model. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Unmet need in healthcare: summary of a roundtable held at the Academy of Medical Sciences on 31 July 2017, held with support from the British Academy and NHS England. AMS 2017. Available from: https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/430378. |

| 91. | What is Supportive Care? MASCC 2023. Available from: https://mascc.org/what-is-supportive-care/. |

| 92. | Olver I, Keefe D, Herrstedt J, Warr D, Roila F, Ripamonti CI. Supportive care in cancer-a MASCC perspective. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:3467-3475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Ktistaki P, Alevra N, Voulgari M. Long-Term Survival of Women with Breast Cancer. Overview Supportive Care Needs Assessment Instruments. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;989:281-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Jordan K, Aapro M, Kaasa S, Ripamonti CI, Scotté F, Strasser F, Young A, Bruera E, Herrstedt J, Keefe D, Laird B, Walsh D, Douillard JY, Cervantes A. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) position paper on supportive and palliative care. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:36-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Klastersky J, Libert I, Michel B, Obiols M, Lossignol D. Supportive/palliative care in cancer patients: quo vadis? Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:1883-1888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer. Available from: https://mascc.org/about-mascc/. |

| 97. | Berman R, Laird BJA, Minton O, Monnery D, Ahamed A, Boland E, Droney J, Vidrine J, Leach C, Scotté F, Lustberg MB, Lacey J, Chan R, Duffy T, Noble S. The Rise of Supportive Oncology: A Revolution in Cancer Care. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2023;35:213-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Davison S, Wearne N, Bagasha P, Krause R. Conservative Kidney Management and kidney Supportive Care: Essential Treatments for Kidney Failure. Med Res Arch. 2023;11. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 99. | Klastersky JA. Editorial: Supportive care: do we need a model? Curr Opin Oncol. 2020;32:257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Berman R, Davies A, Cooksley T, Gralla R, Carter L, Darlington E, Scotté F, Higham C. Supportive Care: An Indispensable Component of Modern Oncology. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2020;32:781-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Kwame A, Petrucka PM. A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nurs. 2021;20:158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 82.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | NEJM Catalyst. What Is Patient-Centered Care? Catalyst Carryover 2017. Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/CAT.17.0559. |

| 103. | Corrigan JM. Crossing the quality chasm. Building a better delivery system. 2005; 89. |

| 104. | Scotté F, Taylor A, Davies A. Supportive Care: The "Keystone" of Modern Oncology Practice. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:3860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Krishnasamy M, Hyatt A, Chung H, Gough K, Fitch M. Refocusing cancer supportive care: a framework for integrated cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2022;31:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Fitch MI. Supportive care framework. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2008;18:6-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Freidin RB. Primary care multidimensional model: a framework for formulating health problems in a primary care setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1980;2:10-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Taberna M, Gil Moncayo F, Jané-Salas E, Antonio M, Arribas L, Vilajosana E, Peralvez Torres E, Mesía R. The Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) Approach and Quality of Care. Front Oncol. 2020;10:85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Epstein NE. Multidisciplinary in-hospital teams improve patient outcomes: A review. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5:S295-S303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Boyd K, Moine S, Murray SA, Bowman D, Brun N. Should palliative care be rebranded? BMJ. 2019;364:l881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Hughes RG. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008. |

| 112. | Titler MG, Kleiber C, Steelman VJ, Rakel BA, Budreau G, Everett LQ, Buckwalter KC, Tripp-Reimer T, Goode CJ. The Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality Care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2001;13:497-509. [PubMed] |

| 113. | ASCO Announces “Top 5” Advances in Modern Oncology 2014. Available from: https://connection.asco.org/magazine/features/asco-announces-%E2%80%9Ctop-5%E2%80%9D-advances-modern-oncology. |

| 114. | Monnery D, Benson S, Griffiths A, Cadwallader C, Hampton-Matthews J, Coackley A, Cooper M, Watson A. Multi-professional-delivered enhanced supportive care improves quality of life for patients with incurable cancer. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2018;24:510-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Stewart E, Tavabie S, McGovern C, Round A, Shaw L, BAss S, Herriott R, Savage E, Young K, Bruun A, Droney J, Monnery D, Wells G, White N, Minton O. Cancer centre supportive oncology service: health economic evaluation. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Shih STF, Mellerick A, Akers G, Whitfield K, Moodie M. Economic Assessment of a New Model of Care to Support Patients With Cancer Experiencing Cancer- and Treatment-Related Toxicities. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16:e884-e892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Antonuzzo A, Vasile E, Sbrana A, Lucchesi M, Galli L, Brunetti IM, Musettini G, Farnesi A, Biasco E, Virgili N, Falcone A, Ricci S. Impact of a supportive care service for cancer outpatients: management and reduction of hospitalizations. Preliminary results of an integrated model of care. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:209-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Penedo FJ, Natori A, Fleszar-Pavlovic SE, Sookdeo VD, MacIntyre J, Medina H, Moreno PI, Crane TE, Moskowitz C, Calfa CL, Schlumbrecht M. Factors Associated With Unmet Supportive Care Needs and Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalizations in Ambulatory Oncology. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2319352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, Scher HI, Kris MG, Hudis C, Schrag D. Overall Survival Results of a Trial Assessing Patient-Reported Outcomes for Symptom Monitoring During Routine Cancer Treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:197-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1560] [Cited by in RCA: 1562] [Article Influence: 195.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Prihodova L, Nagyova I, Rosenberger J, Majernikova M, Roland R, Groothoff JW, van Dijk JP. Adherence in patients in the first year after kidney transplantation and its impact on graft loss and mortality: a cross-sectional and prospective study. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70:2871-2883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Low JK, Williams A, Manias E, Crawford K. Interventions to improve medication adherence in adult kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:752-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Patzer RE, Serper M, Reese PP, Przytula K, Koval R, Ladner DP, Levitsky JM, Abecassis MM, Wolf MS. Medication understanding, non-adherence, and clinical outcomes among adult kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2016;30:1294-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | Massey EK, Meys K, Kerner R, Weimar W, Roodnat J, Cransberg K. Young Adult Kidney Transplant Recipients: Nonadherent and Happy. Transplantation. 2015;99:e89-e96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 124. | Akchurin OM, Melamed ML, Hashim BL, Kaskel FJ, Del Rio M. Medication adherence in the transition of adolescent kidney transplant recipients to the adult care. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18:538-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 125. | Ethical Principles in the Allocation of Human Organs. 2015. Available from: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/professionals/by-topic/ethical-considerations/ethical-principles-in-the-allocation-of-human-organs/#:~:text=The%20principle%20of%20utility%2C%20applied. |