Published online Dec 18, 2024. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v14.i4.95419

Revised: June 11, 2024

Accepted: July 1, 2024

Published online: December 18, 2024

Processing time: 163 Days and 9.3 Hours

Organ donation is a critical issue that is receiving greater attention worldwide. In Jordan, the public’s knowledge about and attitudes toward organ donation play a significant role in the availability of organs for transplantation.

To assess the public knowledge about and attitudes toward organ donation in Jordan.

A cross-sectional design was used to collect data from 396 Jordanian citizens via an online self-reported questionnaire.

Overall, 396 participants were recruited. Of the entire sample, 93.9% of the participants had heard about and had sufficient knowledge about organ donation but they had limited knowledge about brain death. The most common source of information about organ donation was social media networks. Females were found to score significantly higher than males for attitude. Those who had thought about organ donation or registered their names to donate scored signi

Greater public understanding of organ donation appears to be associated with more positive attitudes toward organ donation. Most participants responded positively regarding their attitude toward organ donation as they believed that this action could give another person a chance to live. Moreover, most agreed that they would donate their organs after their death. Otherwise, the participants had limited general knowledge about brain death, and most had not registered their names to donate their organs. These findings indicate the need for public awareness campaigns and educational programs to encourage more people to become organ donors.

Core Tip: This study sheds light on Jordanian public knowledge and attitudes toward organ donation. Fortunately, our results showed adequate knowledge and favored attitudes toward organ donation, which could be invested to increase the number of organ donors. However, lack of awareness programs, inadequate understanding of brain death, fear of side effects, or fear of falling into organ trafficking may hinder organ donation practices in Jordan. We can create a more informed and willing society to participate in organ donation by implementing comprehensive education efforts through community outreach campaigns, school curriculums, and media campaigns to increase awareness about organ donation.

- Citation: Al-Salhi A, Othman EH. Public knowledge about and attitudes toward organ donation, and public barriers to donate in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. World J Transplant 2024; 14(4): 95419

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v14/i4/95419.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v14.i4.95419

An organ transplant is a medical procedure in which an organ is transplanted from one body to another, and it might be conducted for patients suffering end-stage organ failure. An organ transplant might be the only therapeutic option for patients with irreversible chronic or acute diseases such as liver failure[1,2]. Furthermore, for those with renal failure, dialysis could be costly compared to an organ transplant, while their quality of life could be improved by an organ transplant[2]. The latest data reveal a need for increased and substantial organ donation. The donation process is an invaluable life gift, with one organ donor potentially able to save eight lives[3].

The number of organ donors has increased over the years owing to public education, awareness activities, and outreach initiatives aimed at securing deceased organ donations[4]. Nevertheless, the number of patients who need life-saving organ transplants continues to exceed the number of available organs[5]. A major deficit exists between the number of people waiting for an organ and the number of organ donors. For instance, the number of deceased kidney donors fell by 25% in 2020-2021 compared to 2019-2020, while 3525 patients were waiting for a kidney transplant on 31 March 2021 in the United Kingdom alone[6]. Similar concerns have arisen in Canada; despite efforts to increase organ donation rates, the country continues to face challenges in meeting the growing demand for organs because the demand far exceeds the supply, leading to long wait times for patients in need of a transplant. In 2018, 4,351 individuals in Canada were awaiting organ transplants, of whom 805 were in Quebec, while 223 Canadians died while on the transplant waiting list[7].

For many years, information on donation and transplantation activity in Europe has been published in an annual Council of Europe Transplant Newsletter. This shows that most European countries have major shortages of donors but longer transplantation waiting lists[8]. These long lists mean that most patients with end-stage organ disease die before organs are available. For example, in Italy, the continuing organ transplant shortage means many patients are still on waiting lists. The Italian National Transplantation Centre reported a consistent number of patients awaiting trans

Meanwhile, Spain has been recognized as having the highest rate of organ donors worldwide, which has been attributed to its presumed consent model and multi-level transplant coordination system. The transplant system is widely trusted, leading to a strong desire to donate organs after death and authorize organ removal by family members. These positive perceptions are due to the efforts of the Spanish government and healthcare organizations to promote organ donation awareness through public campaigns[10].

Among Arab countries, only Saudi Arabia and, to a lesser extent, Jordan and Kuwait, have good reputations regarding transfers of organs, which come primarily from live rather than dead donors. However, the donation percentages are minimal compared with European levels[11]. Further, there are major deficits between the number of patients on waiting lists and the number of organs available to them, according to the population census taken in each Arab country[12].

Several donation challenges confront the Arab world, including a lack of public education and awareness. Many programs have been established in Europe to improve local community awareness of organ donation and its benefits; however, these programs are limited in the Middle East[4,13]. Other challenges include a lack of approval and support by Islamic scholars, as well as a lack of government infrastructure and financial resources[12,14]. Economic conditions represent another challenge; due to the poverty and deaths caused by wars and malnutrition, organ transplant is not a health priority in Middle Eastern countries[14].

According to the Jordan Center for Organ Transplantation Directorate of the Jordanian Ministry of Health, the number of transplant operations in Jordan reached 1753 between 2011 and 2018, including 1643 kidneys, 110 Livers, and only one heart transplant. Only 11 of the 1753 were brain death cases[15]. In the same context, according to the Private Hospital Association, only living first-degree related kidney and liver donors (such as from parents, siblings, spouses, aunts, and uncles) are allowed in Jordan, and donors should be between 18-years-old and 65-years-old[16]. Given that organ donation is only permitted for a first-degree relation, finding donors might be an obstacle to increasing the donation rate in Jordan.

Deciding about organ donation is an important and complicated decision for the person and his/her family. Some might question what would happen to their organ/s after donation or wonder whether surgery would affect their health[17,18]. Likewise, brain death is considered to prompt hugely difficult decisions because relatives can see that a patient is still breathing and their heart is still pumping blood, which often means that to family members, they remain alive[19,20]. However, most countries accept that brain death is the complete death of a person, while most religions recognize it as the death of an individual[21,22]. The Middle East was among the first regions to accept this concept; this recognition occurred at the conference of the Council on Islamic Jurisprudence held in Amman, Jordan in 1987[23].

To the best of the researchers’ current knowledge, no previous study has examined public awareness of and attitudes toward organ donation. Therefore, this study will be the first to examine aspects that might hinder people in Jordan and similar Middle Eastern cultures from donating. The purpose of the study was to assess public knowledge about and attitudes toward organ donation in Jordan.

A cross-sectional design was employed, with data collected via an online self-reported questionnaire issued to the Jordanian population. The study targeted Jordanian citizens living in different Jordanian governorates across different regions. Convenience sampling was conducted using an electronic link on Google documents, which was distributed through a link sent personally or via social networks. The use of social networks helped in reaching potential Jordanian participants in distant governorates. All Jordanian citizens: (1) Over 18-years-old; and (2) Able to read and comprehend Arabic were eligible to participate in the study without any restrictions.

Data were collected using a self-reported questionnaire distributed via an electronic link. The questionnaire was developed by the researchers and contained questions about their demographic characteristics; whether they or any of their first-degree relatives suffered from chronic illnesses; their knowledge about organ donation and brain death, measured as true/false questions, with a score of one given to correct answers and a score of zero given to incorrect answers; their sources of information about organ donation and brain death; their attitudes toward organ donation; and reasons why organ donation practices in Jordan were limited.

Attitudes toward organ donation were measured using the Public’s Attitude and Beliefs about Organ Donation instrument[24], which consists of 31 questions measured on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with a total score range of between 0 and 124. Higher scores reflect more favorable attitudes toward organ donation. The items comprised four subscales: (1) Opinions about organ donation (nine items); (2) Preferences for organ donation (eight items); (3) Perceived risks of living organ donation (six items); and (4) Hesitation about and barriers to organ donation (8 items). The Cronbach’s alpha value for the study scale was 0.81. The Cronbach’s alpha value for the “Opinions about organ donation” subscale, The “Preferences for organ donation” subscale, the “Hesitation about and barriers to organ donation” subscale, and the “Perceived risks of organ donation” subscale were 0.88, 0.90, 0.83, and 0.76, respectively.

Ethical approval to conduct this study was granted by the Scientific Research Committee at the Faculty of Nursing, Applied Science Private University. All ethical considerations were maintained throughout the study. Implied consent was used, whereby simply responding to the electronic questionnaire was deemed acceptance to participate.

The Social Package for Statistical Analysis (SPSS-version 26; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) was utilized to run the analysis (at a significance level of less than 0.05). Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and frequencies) were used to describe the sample and main study variables (knowledge about, attitudes to, and barriers to donation). Lastly, the t-test and one-way ANOVA examined the differences in the participants’ responses based on their characteristics.

The total sample consisted of 396 participants. More than half of them were females (n = 208, 52.7%) between 20-years-old and 35-years-old (n = 208, 52.5%), and held a Bachelor’s degree (n = 258, 65.2%). The participants’ demographics are presented in full in Table 1.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 208 (52.7) |

| Male | 188 (47.3) |

| Age in years | |

| 18-35 | 235 (59.3) |

| 36-55 | 121 (30.6) |

| > 55 | 40 (10.1) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 206 (52) |

| Married | 171 (43.2) |

| Others, divorced or widowed | 19 (4.8) |

| Educational level | |

| Less than high school | 53 (13.4) |

| Diploma | 54 (13.6) |

| BSc | 258 (65.2) |

| Higher education | 31 (7.8) |

| Employment | |

| Full-time job | 146 (36.9) |

| Part-time job | 43 (10.9) |

| Not working | 207 (52.3) |

| Monthly income in JD | |

| < 500 | 123 (31.1) |

| 500-999 | 157 (39.6) |

| 1000-1500 | 70 (17.7) |

| > 1500 | 46 (11.6) |

| Residency | |

| Urban | 362 (91.4) |

| Rural | 34 (8.6) |

The participants were asked to state if they or any of their first-degree relatives suffered from chronic illnesses (Table 2). Overall, 342 (86.4%) participants had no chronic illnesses, while only 80 (20.2%) declared that their relatives had no chronic illnesses. Further, the most common chronic illnesses among the participants and their relatives were cardiac diseases, (n = 17, 4.3% and n = 135, 34.1%, respectively).

| Related organ | Participant | Relatives |

| Heart | 17 (4.3) | 135 (34.1) |

| Pancreas | 10 (2.5) | 46 (11.6) |

| Kidney | 9 (2.3) | 45 (11.4) |

| Lung | 8 (2) | 39 (9.8) |

| Small intestine | 10 (2.5) | 34 (8.6) |

| Liver | 0 | 17 (4.3) |

| None | 342 (86.4) | 80 (20.2) |

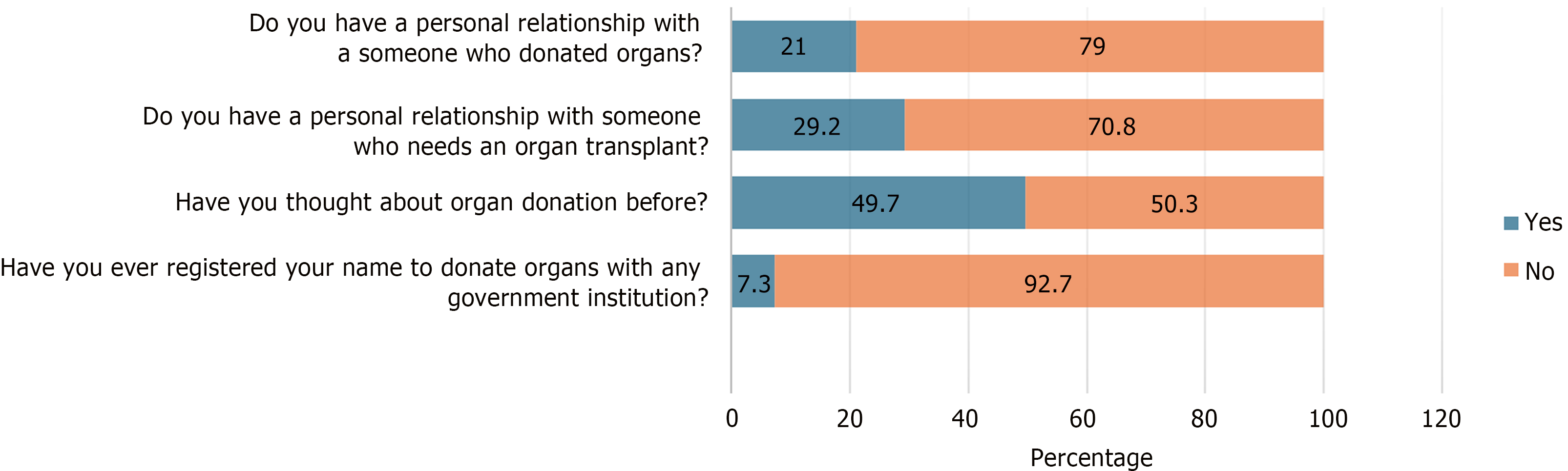

Further, the participants were first asked if they had a relationship with a donor or organ recipient and, secondly, if they had thought about organ donation or registered their names to donate (Figure 1). Of the 396 participants, 83 (21%) had a personal relationship with someone who had donated organs, and 116 (29.3%) had a personal relationship with someone needing an organ transplantation. Although 49.7% of the participants (n = 197) had thought about organ donation, only 7.3 % (n = 29) had actually registered their names with governmental institutions in order to donate.

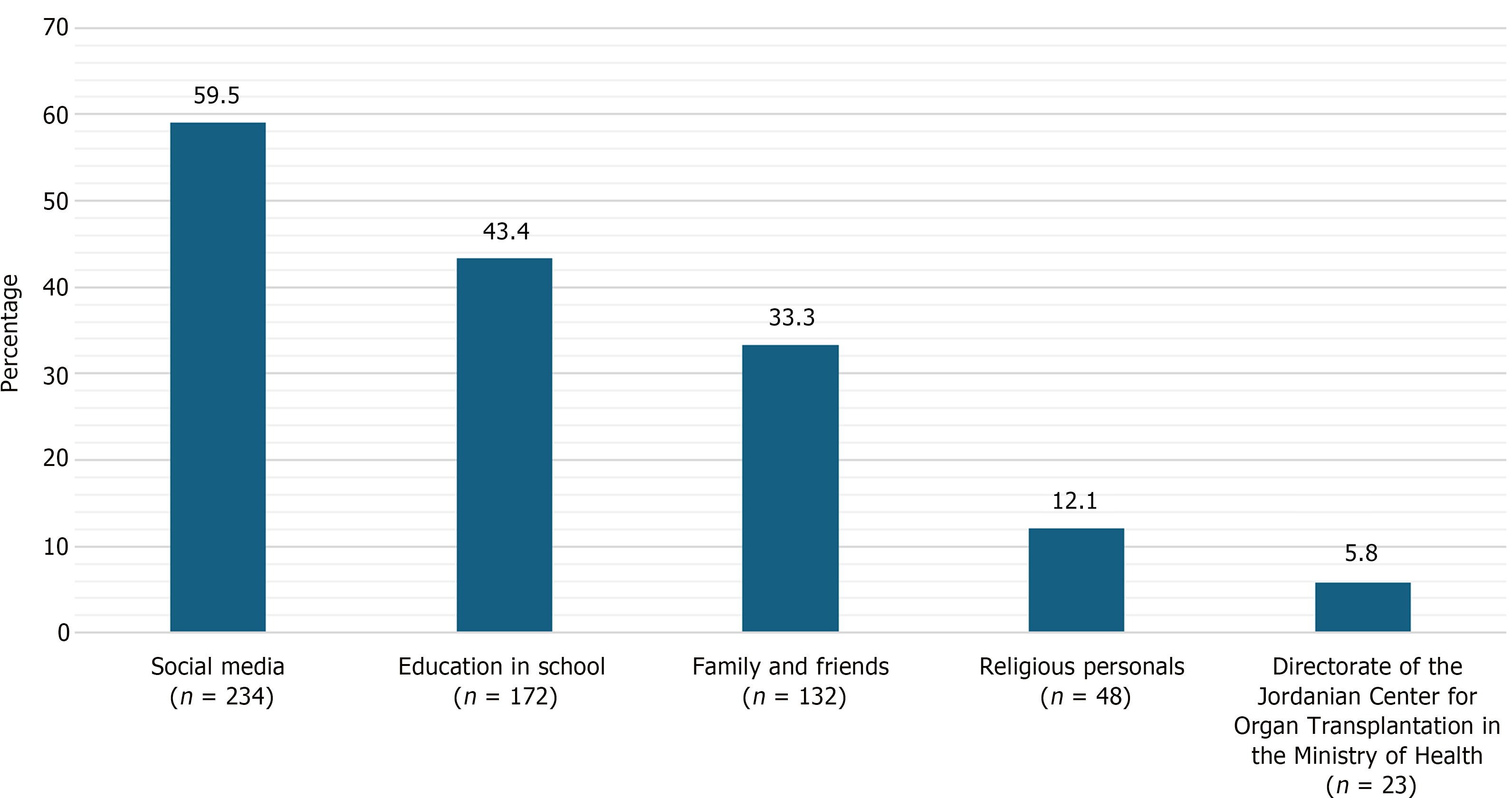

Of the entire sample, 372 participants (93.9%) had heard about organ donation. They were asked to list the sources of their information (Figure 2). The most common source of information about organ donation was “social media networks” (n = 234, 59.1%), followed by “education in school” (n = 172, 43.4%).

The participants were asked several questions to assess what they knew about organ donation and brain death (Table 3). Most participants defined organ donation correctly (n = 371, 93.7%). Regarding their knowledge about which organs could be donated, most participants selected the kidney (95.2%), cornea (88.4%), heart (80.3%), liver (78%), and bone marrow (70.5%). On the other hand, skin was selected by only 46.7% of the participants, and lungs were selected by 52.8%.

| Question | Correct answer | Incorrect answer |

| Organ donation is when a person donates one or more parts of his body during his life or after his death to another person | 371 (93.7) | 25 (6.3) |

| The blood group of the donor and the patient must match when transplanting organs | 284 (71.7) | 112 (28.3) |

| Human kidney can be transplanted | 377 (95.2) | 19 (4.8) |

| Human corneal can be transplanted | 350 (88.4) | 46 (11.6) |

| Human heart can be transplanted | 318 (80.3) | 78 (19.7) |

| Human liver can be transplanted | 309 (78) | 87 (22) |

| Human bone marrow can be transplanted | 279 (70.5) | 117 (29.5) |

| Human lung can be transplanted | 209 (52.8) | 187 (47.2) |

| Human skin can be transplanted | 185 (46.7) | 211 (53.3) |

| Brain death is the irreversible cessation of all brain functions, which means that a brain-dead person does not have the ability to exercise vital functions such as breathing without artificial support devices and medications | 341 (86.1) | 55 (13.9) |

| Even if the doctor declares brain death, the patient is alive as long as he is breathing | 51 (12.9) | 345 (87.1) |

| Even if the doctor declares brain death, the patient may recover from his injuries | 211 (53.3) | 185 (46.7) |

| Even if the doctor declares brain death, taking the patient's organs is forbidden by religion (Sharia) | 66 (16.7) | 330 (83.3) |

| Even if the doctor declares brain death, taking the patient's organs is immoral | 60 (15.2) | 336 (84.8) |

In terms of knowledge about brain death, most participants defined it correctly (n = 34, 86.1%). However, a high percentage considered patients to be alive even if they had been diagnosed as brain dead (n = 345, 87.15%). In the same context, while most participants knew that patients with brain death would not recover from their injuries (n = 211, 53.3%), they considered that taking a patient's organs was immoral (n = 336, 84.8%) or even forbidden by religion (n = 330, 83.3%).

The total score for participants’ attitudes toward organ donation was 72.78 ± 18.36 out of 124, (min = 25, max = 120). Table 4 shows the total scores for the attitude subscales.

| Subscale | Total score M (SD) | Min-Max | 95%CI | |

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Total Attitude scale (out of 124) range | 72.78 (18.36) | 25-120 | 70.96 | 74.60 |

| Opinions about organ donation (out of 36) range | 24.29 (8.42) | 0-36 | 23.46 | 25.13 |

| Preferences for organ donation (out of 32) range | 17.41 (9.23) | 0-32 | 16.50 | 18.33 |

| Perceived risks of living organ donation (out of 24) range | 13.15 (7.43) | 0-24 | 12.41 | 13.88 |

| Hesitations and barriers to organ donation (out of 32) range | 17.39 (7.56) | 0-32 | 17.18 | 18.68 |

To further understand the participants’ attitudes, their responses for each item were categorized as agree, neutral, or disagree, as seen in Table 5. Most participants believed that organ donation was an ongoing form of charity (n = 304, 76.8%) and that it could transform the experience of death into a happy one by giving another person a chance to live (n = 294, 74.2%). Furthermore, most participants believed that organ donation could give another person a chance to live (n = 294, 74.2) and comfort the patient’s family because they would know that a part of them was still alive (n = 240, 60.6%). In terms of the decision to donate, most participants agreed that they would donate after their death (n = 210, 53%), and 68.4% (n = 271) agreed that they would donate to a family member during their life. Meanwhile, a higher percentage of participants would consent to donate the organs of a deceased family member if they knew that he/she wanted to be a donor compared to a situation in which the wishes of the deceased were unknown (n = 269, 67.9% vs n = 192, 48.5%).

| Items | Disagree | Neutral | Agree |

| Opinions about organ donation | |||

| I believe that organ donation is a permanent good deed that benefits the community (ongoing charity) | 37 (9.3) | 55 (13.9) | 304 (76.8) |

| I believe that organ donation after death can transform the experience of death into a happy one by giving another person a chance to live | 48 (12.1) | 54 (13.6) | 294 (74.2) |

| If it was up to me, I would give consent to donate the organs of a family member when he dies, only if I knew he wanted to be a donor | 62 (15.7) | 65 (16.4) | 269 (67.9) |

| In my opinion, the donor’s family feels comfortable after his death because part of him is still alive in the body of another person | 65 (16.4) | 91 (23) | 240 (60.6) |

| I don’t agree to donate my organs after my death | 210 (53) | 84 (21.2) | 102 (25.8) |

| If it was up to me, I would give consent to donate the organs of a family member when he dies | 118 (29.8) | 86 (21.7) | 192 (48.5) |

| I encourage my family members to donate organs | 134 (33.8) | 140 (35.4) | 122 (30.8) |

| I agree to donate organs during my life to a member of my family | 65 (16.4) | 60 (15.2) | 271 (68.4) |

| I agree to donate organs regardless of the recipient’s attributes, as long as he/she needs it | 95 (24) | 79 (19.9) | 222 (56.1) |

| Preferences for organ donation | |||

| I prefer to donate to someone who is not an alcoholic | 123 (31.1) | 58 (14.6) | 215 (54.3) |

| I prefer to donate to non-smokers | 180 (45.4) | 83 (21) | 133 (33.6) |

| I prefer to donate to someone without any physical disability or disease other than what is related to the donated organ | 187 (47.2) | 106 (26.8) | (26) |

| I prefer to donate to someone who shares my religious beliefs | 154 (38.9) | 81 (20.5) | 161 (40.7) |

| I prefer to donate to someone who is under the age of 50 years | 165 (41.7) | 97 (24.5) | 134 (33.8) |

| I prefer to donate to someone without any psychological disorder or mental disability | 184 (46.5) | 89 (22.5) | (31) |

| I prefer to donate to someone who has not been criminally convicted | 166 (41.9) | 102 (25.8) | 128 (32.3) |

| I prefer to donate to someone from my own tribe | 192 (48.5) | 105 (26.5) | 99 (25) |

| Perceived risks of living organ donation | |||

| Living donation entails the risk of causing pain to the donor | 150 (37.9) | 34 (8.6) | 212 (53.5) |

| Living donation entails the risk of causing infections to the donor | 150 (37.9) | 47 (11.8) | 199 (50.3) |

| Organ donation during life causes no risks or harms | 305 (77) | 20 (5.1) | 71 (17.9) |

| Living donation entails the risk of causing bleeding to the donor | 227 (57.3) | 10 (2.5) | 159 (40.2) |

| Living donation entails the risk of causing weakness in the donor | 160 (40.4) | 33 (8.3) | 203 (51.3) |

| Living donation entails the risk of causing psychological harm, such as stress, anxiety, or depression, to the donor | 205 (51.8) | 16 (4) | 175 (44.2) |

| Hesitations and barriers to organ donation | |||

| I may hesitate to donate organs because the body might be deformed if its organs are removed | 207 (52.3) | 91 (23) | 98 (24.7) |

| I may hesitate to donate organs because I believe it is essential that the human body contains all its parts when it is buried | 231 (58.3) | 73 (18.4) | 92 (23.2) |

| I may hesitate to donate organs because my family does not approve of it | 172 (43.4) | 117 (29.5) | 107 (27) |

| I may hesitate to donate organs because I fear side effects, medications, and surgeries | 79 (19.9) | 115 (29) | 202 (51) |

| I may hesitate to donate organs because I don't like the idea of giving up one of my organs, I might need it in the future | 145 (36.6) | 106 (26.8) | 145 (36.6) |

| I may hesitate to donate organs because I lack trust in the medical staff | 183 (46.2) | 112 (28.3) | 101 (25.5) |

| I may hesitate to donate organs because my religious beliefs are not compatible with organ donation | 249 (62.9) | 86 (21.7) | 61 (15.4) |

| I may hesitate to donate organs because I fear falling into the network of organ trafficking | 139 (35.1) | 74 (18.7) | 183 (46.2) |

Regarding preferences about organ donation, most participants preferred donating to non-alcoholic patients (n = 215, 54.3%) and those sharing their own religious beliefs (n = 161, 40.7%). On the other hand, the participants’ decisions to donate their organs would be unaffected by the patient's smoking habit, the presence of any medical or psychiatric illness, their age, their criminal history, or the fact that they were not a member of their tribe (extended family).

The majority of the participants stated that living organ donation harmed the donor (n = 305, 77%). The risks and harm of living donation, as perceived by the participants, were pain (n = 212, 53.5%), weakness (n = 203, 51.3%), infection (n = 199, 50.3%), stress, anxiety, or depression (n = 175, 44.2%), and bleeding (n = 159, 40.2%).

Lastly, the most common reason for hesitation to donate was fear of side effects, medications, and surgery (n = 202, 51%), followed by fear of becoming a victim of organ trafficking (n = 183, 46.2%). In contrast, the least frequently reported reasons for hesitation were religious beliefs, (n = 61, 15.4%), the notion that the human body must contain all its parts when buried (n = 92, 23.2%), and the possibility that the body might be deformed after organ removal (n = 98, 24.7%).

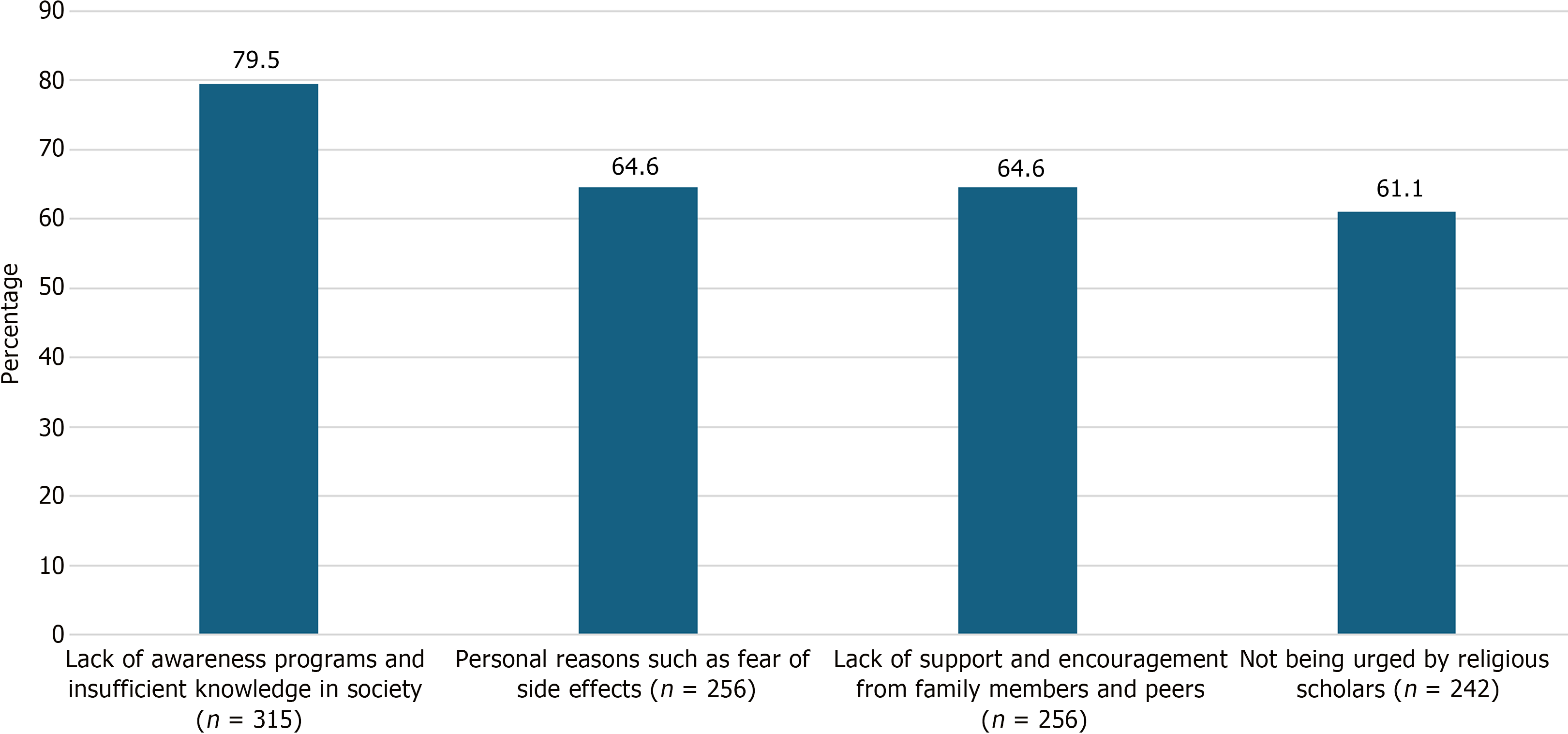

The participants were asked to specify reasons why organ donation practices in Jordan were limited, with their answers displayed in Figure 3. The most common reason was “Lack of awareness programs and insufficient knowledge in society” (n = 315, 79.5%), followed by “Fear of side effects” (n = 256, 64.6%) and “Lack of support and encouragement from family members and peers” (n = 256, 64.6%).

The only significant difference in attitude was based on sex (Table 6). Female participants exhibited a significantly better attitude score (M = 74.41, SD = 18.39) than males (M = 68.35, SD = 17.59), t (392) = 2.93, P =0.004. Those who had thought about organ donation [t (392) = 7.62, P < 0.001] or registered their names to donate [t (392) = 2.42, P =0.02] scored significantly higher in terms of attitude to donation (M = 79.41, SD = 17.46 and M = 78.96, SD = 14.41, respectively) than their counterparts who had not considered donation (M = 66.22, SD = 16.84 and M = 72.31, SD = 18.56, respectively). Relationships with someone who had donated organs or someone who needed an organ transplantation did not affect the participants’ attitudes toward donation.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Test | P value |

| Sex | 2.93 | 0.004 | |

| Female | 74.41 (18.39) | ||

| Male | 68.35 (17.59) | ||

| Age in years | 2.16 | 0.116 | |

| 18-35 | 73.14 (17.71) | ||

| 36-55 | 73.96 (19.46) | ||

| > 55 | 67.18 (18.14) | ||

| Marital status | 0.89 | 0.446 | |

| Single | 72.92 (18.02) | ||

| Married | 73.11 (18.90) | ||

| Others, divorced or widowed | 79.33 (17.36) | ||

| Educational level | 1.64 | 0.181 | |

| Less than high school | 72.62 (20.61) | ||

| Diploma | 67.91 (18.33) | ||

| BSc | 73.95 (17.89) | ||

| Higher education | 71.71 (17.70) | ||

| Employment | 1.35 | 0.258 | |

| Full time job | 74.34 (17.16) | ||

| Part timer job | 69.26 (19.24) | ||

| Not working | 72.41 (18.95) | ||

| Monthly income in JD | 0.42 | 0.737 | |

| < 500 | 18.54 (1.68) | ||

| 500-999 | 18.47 (1.47) | ||

| 1000-1500 | 18.73 (2.24) | ||

| > 1500 | 17.20 (2.54) | ||

| Residency | 0.93 | 0.351 | |

| Urban | 73.04 (18.27) | ||

| Rural | 69.94 (19.37) | ||

| History of chronic illnesses | 1.02 | 0.413 | |

| Yes | 72.17 (16.96) | ||

| No | 72.88 (18.59) | ||

| Chronic illnesses of relatives | 0.945 | 0.45 | |

| Yes | 72.82 (17.52) | ||

| No | 72.74 (19.16) | ||

| Do you have a personal relationship with a person who donated organs? | 0.803 | 0.44 | |

| Yes | 74.23 (18.61) | ||

| No | 72.40 (18.30) | ||

| Do you have a personal relationship with someone who needs an organ transplant? | 1.36 | 0.17 | |

| Yes | 74.75 (18.89) | ||

| No | 71.97 (18.10) | ||

| Have you thought about organ donation before? | 7.62 | < 0.001 | |

| Yes | 79.41 (17.46) | ||

| No | 66.22 (16.84) | ||

| Have you ever registered your name to donate organs with any government institution? | 2.42 | 0.02 | |

| Yes | 78.96 (14.41) | ||

| No | 72.31 (18.56) |

The decision to donate organs may be one of the most difficult decisions to take as it creates a dilemma between helping someone who needs an organ to save their life and keeping organs and not donating them. In terms of brain death, not knowing whether a patient has died or whether he/she might recover is a tragedy for the family. This prompted the desire to determine how much people in Jordan know about these two critical issues, their attitudes toward organ donation, and the obstacles that might prevent them from donating. Fortunately, most participants did not suffer from any chronic diseases, in contrast to their relatives, with the results showing that most participants had relatives suffering from such diseases. The majority suffered from diseases of the heart, kidneys, or pancreas, indicating a high possibility that they would need an organ.

A study conducted in England involving 119 participants is comparable to the current study in terms of people’s knowledge of the term ‘organ donation’ and their personal relationships with organ donors[25]. A similar percentage of people in each study had heard the term ‘organ donation’ [95% (n = 113) in England and 94% (n = 372) in this study], indicating acceptable worldwide knowledge of the term.

Most participants in this study (n = 234, 59%) had heard about organ donation through social media, which contradicts an Indian study in which most participants had heard about organ donation through doctors and hospitals (47%), while social media was one of the least reported sources, at only 4%[26]. This finding raises concerns that authorized personnel display insufficient participation in bridging the knowledge gap regarding organ donation and transplantation among Jordanian citizens, especially since social media and unofficial sources could spread false information about these concepts.

Educational campaigns, official sites, and community outreach programs are effective ways to raise awareness about organ donation. Nevertheless, the results of the current study indicate that many participants had not heard about organ donation from an official governmental institution. This is alarming because awareness campaigns about the importance of organ donation must originate from official bodies to ensure the quality and reliability of shared information.

The discussion about people’s knowledge about organ donation mentioned many important questions about the extent of this knowledge. Understanding what people know about organ donation is essential to ascertain the general desire to donate organs, which ultimately increases the number of people willing to donate. There is a general understanding of what organ donation is, according to the findings, with the majority able to identify the concept of organ donation: Only 6.3% answered this question incorrectly. In their answers about organs that can be donated, more than 70% listed the kidneys, cornea, heart, liver, and bone marrow as organs for possible donation. However, nearly 50% did not know that the lungs and skin could be donated, perhaps due to the limited number of donation surgeries involving these organs in Jordan. The current results are comparable to those of a study conducted in Malaysia, where 80.2% of the respondents (n = 307) were aware of which organs can be transplanted and 88.8% (n = 339) could define ‘organ donation’[27]. The same study revealed that 77.3% (n = 296) of the participants correctly defined brain death, and 59.3% (n = 227) agreed that brain-dead patients cannot recover and that their condition is irreversible[27].

The results of this study can be compared with other studies undertaken in the Arab world, including research conducted in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 2018 involving 1244 participants, which aimed to ascertain the Saudi population’s knowledge about brain death. The results showed that nearly half of the participants believed that a patient with brain death might recover from his/her injuries, while most believed that a brain-dead patient is alive as long as he/she is breathing, which meant they did not consider brain death to be the real death of the patient. These numbers are similar to those obtained in the study by AlQahtani and Mahfouz, in which 707 (56.7%) participants believed that a brain-dead patient could be cured, while 74% did not consider brain death to be real death[28]. In another study conducted in Syria, nearly half of the participants linked brain death to coma[29]. These results indicate a widespread public misunderstanding of the concept of brain death, which will prevent people from deciding to donate organs. As long as people believe a patient might recover from brain death or that he/she is still alive, they will find it difficult to accept the idea of organ donation.

The participants in this study had favorable attitudes toward organ donation, with the majority believing that organ donation could save another person’s life. More than half agreed to donate after their death, and even a higher percentage agreed to donate to a family member while still alive. However, the new figures are lower than those obtained in other studies in the Arab world; in research from Tunisia, almost 80.7% of the participants agreed to donate their organs after death[30]. This difference might be linked to the limited awareness campaigns and initiatives regarding organ donation in Jordan. The current study revealed that women participants scored significantly better for attitude compared to men, which contradicts a study conducted in Turkey, where men showed more willingness to donate than women[31]. In a study conducted in Pakistan, participants were asked about possible reasons for not donating their organs; 27.6% chose "religion," while 24.9% chose "risk to personal health"[32]. Of the participants in the new study, the most common reason for hesitating to donate was fear of side effects, medications, and surgeries, followed by fear of becoming a victim of organ trafficking. In contrast, the least reported reason for hesitation was religious beliefs. Again, these misconceptions could be corrected with appropriate awareness campaigns.

Barriers to organ donation differ between countries because organ donation is closely related to death, which has always had complex, multifaceted dimensions, including religious, philosophical, cultural, and medical. The results of this study indicate that over 60% of the participants confirmed that Jordan has barriers to organ donation. The most important of these, the participants indicated, were a lack of awareness programs and insufficient knowledge in society. In an Indian study, it was confirmed that a lack of education programs on organ donation and transplantation was one of the main reasons for the organ shortage[33]. Besides a lack of knowledge, the participants identified a fear of side effects and a lack of peer and family support as possible causes. In a study conducted to investigate the low rate of organ donation among Asian Americans, the participants stated that cultural disapproval of organ donation discussions was common due to the belief that talking about death and dying can bring bad luck[34]. Another study conducted in Bangladesh also confirmed the lack of family support regarding the decision to donate organs. The same study also indicated that the vast majority of the participants believed that their bodies belong to Allah, so they cannot decide what to do with their bodies[35]. The participants in the current study also believed that donation is forbidden by religion and mentioned inadequate encouragement by religious scholars as a barrier against organ donation. The Muslim Law (Sharia) Council in the United Kingdom issued a Fatwa (a religious edict) in 1995 saying that organ donation was permitted, although people were still ignorant about whether it was forbidden or not[36]. Society’s insufficient knowledge about organ donation represents a critical challenge to increasing the number of available organs and saving the lives of patients in need.

Several recommendations can be made to increase organ donation rates in Jordan. Comprehensive education efforts should be implemented through community outreach programs, integration into the school curriculum, and media campaigns to increase organ donation awareness. Moreover, given that healthcare providers know about organ donation and have direct contact with patients, understanding their role in raising organ donation awareness is another area worth researching. A more informed society willing to participate in organ donation programs could be created by combining extensive education campaigns with a healthcare system that promotes organ donation awareness.

The current study is one of the earliest to investigate organ donation among Jordanian citizens, providing a large base of information that could be used to build future research studies. One of its limitations is that using an online data collection questionnaire precluded access for those without internet connections. Another limitation is the failure to use a valid tool for measuring participants’ knowledge, which can be justified in two main ways: (1) The authors could not find a satisfactory questionnaire that met the cultural properties of the study population; and (2) measuring knowledge was not the primary aim of the study, nor was measuring the relationship between knowledge and attitude, as this relationship has been extensively addressed in previous studies.

The current study highlights public knowledge about and attitudes toward organ donation in Jordan because it is crucial to address the shortage of organs available for transplantation. Fortunately, the results were generally positive in both respects and could be utilized to increase the number of organ donation registrations. On the other hand, the findings revealed a lack of understanding of brain death, fear of side effects, and fear of becoming an organ trafficking victim, as factors that might prevent individuals from registering as donors.

| 1. | Abdelfattah MR, Al-Sebayel M, Broering D. An analysis of outcomes of liver retransplant in adults: 12-year’s single-center experience. Exp Clin Transplant. 2015;13. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Rykhoff ME, Coupland C, Dionne J, Fudge B, Gayle C, Ortner TL, Quilang K, Savu G, Sawany F, Wrobleska M. A clinical group's attempt to raise awareness of organ and tissue donation. Prog Transplant. 2010;20:33-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Donation and Transplant Institute. IRODaT-2020 preliminary numbers in organ donation and transplantation. 2021. [cited Mar 2, 2022]. Available from: https://tpm-dti.com/irodat-2020-preliminary-numbers-in-organ-donation-and-transplantation. |

| 4. | Manyalich M, Guasch X, Paez G, Valero R, Istrate M. ETPOD (European Training Program on Organ Donation): a successful training program to improve organ donation. Transpl Int. 2013;26:373-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Larijani B, Zahedi F, Taheri E. Ethical and legal aspects of organ transplantation in Iran. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:1241-1244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | National Health Service Blood and Transplant. Annual Activity Report of Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation 2020-2021. 2021. Available from: https://www.odt.nhs.uk/statistics-and-reports/annual-activity-report/. |

| 7. | Robert P, Bégin F, Ménard-Castonguay S, Frenette AJ, Quiroz-Martinez H, Lamontagne F, Belley-Côté EP, D'Aragon F. Attitude and knowledge of medical students about organ donation - training needs identified from a Canadian survey. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Newsletter Transplant 2020. 2020. Council of Europe. Available from: https://www.edqm.eu/en/-/newsletter-transplant-2020-est-disponible. |

| 9. | Terraneo M, Caserini A. Information matters: attitude towards organ donation in a general university population web-survey in Italy. IJSSP. 2022;42:1-14. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Díaz-Cobacho G, Cruz-Piqueras M, Delgado J, Hortal-Carmona J, Martínez-López MV, Molina-Pérez A, Padilla-Pozo Á, Ranchal-Romero J, Rodríguez-Arias D. Public Perception of Organ Donation and Transplantation Policies in Southern Spain. Transplant Proc. 2022;54:567-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abouna GM. Ethical issues in organ transplantation. Med Princ Pract. 2003;12:54-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Abouna GM. The humanitarian aspects of organ transplantation. Transpl Int. 2001;14:117-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Roels L, Rahmel A. The European experience. Transpl Int. 2011;24:350-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Galal A, Selim H. The Elusive Quest for Economic Development in the Arab Countries. Middle East Dev J. 2013;5:1350002-1. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Jordan Center for Organs Transplantation Directorate. 2018. Ministry of health. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.jo/Default/En. |

| 16. | Private hospitals association Jordan. Organ Transplant. 2021. Available from: https://phajordan.org/View_Article.aspx?type=2&ID=3878. |

| 17. | Krupic F, Sayed-Noor AS, Fatahi N. The impact of knowledge and religion on organ donation as seen by immigrants in Sweden. Scand J Caring Sci. 2017;31:687-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vincent A, Logan L. Consent for organ donation. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108 Suppl 1:i80-i87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chatterjee K, Rady MY, Verheijde JL, Butterfield RJ. A Framework for Revisiting Brain Death: Evaluating Awareness and Attitudes Toward the Neuroscientific and Ethical Debate Around the American Academy of Neurology Brain Death Criteria. J Intensive Care Med. 2021;36:1149-1166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gillian T. Brain death and the philosophical significance of the process of development of, and cessation of, consciousness in arousal and awareness in the human person. Linacre Q. 2001;68:32-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wijdicks EF. The diagnosis of brain death. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1215-1221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 453] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Miller AC, Ziad-Miller A, Elamin EM. Brain death and Islam: the interface of religion, culture, history, law, and modern medicine. Chest. 2014;146:1092-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Masri MA, Haberal MA, Shaheen FA, Stephan A, Ghods AJ, Al-Rohani M, Mousawi MA, Mohsin N, Abdallah TB, Bakr A, Rizvi AH. Middle East Society for Organ Transplantation (MESOT) Transplant Registry. Exp Clin Transplant. 2004;2:217-220. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Othman EH, Al-Salhi A, AlOsta MR. Public Attitudes and Beliefs About Organ Donation: Development and Validation of a New Instrument. J Nurs Meas. 2024;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Coad L, Carter N, Ling J. Attitudes of young adults from the UK towards organ donation and transplantation. Transplant Res. 2013;2:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Balwani MR, Gumber MR, Shah PR, Kute VB, Patel HV, Engineer DP, Gera DN, Godhani U, Shah M, Trivedi HL. Attitude and awareness towards organ donation in western India. Ren Fail. 2015;37:582-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lim KJ, Cheng TTJ, Jeffree MS, Hayati F, Cheah PK, Nee KO, Ibrahim MY, Shamsudin SB, Robinson F, Awang Lukman K, Mohd Yusuff AS, Swe, Oo Tha N. Factors Influencing Attitude Toward Organ and Tissue Donation Among Patients in Primary Clinic, Sabah, Malaysia. Transplant Proc. 2020;52:680-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | AlQahtani BG, Mahfouz MEM. Knowledge and awareness of brain death among Saudi population. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2019;24:207-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tarzi M, Asaad M, Tarabishi J, Zayegh O, Hamza R, Alhamid A, Zazo A, Morjan M. Attitudes towards organ donation in Syria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21:123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Aissi W, Kaffel N, Bardi R, Sfar I, Gorgi Y, Ben Abdallah T, Gargah T, Ziadi J. Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Organ Donation Among Tunisian Adults: Results of a National Survey. Exp Clin Transplant. 2024;22:224-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Güden E, Cetinkaya F, Naçar M. Attitudes and behaviors regarding organ donation: a study on officials of religion in Turkey. J Relig Health. 2013;52:439-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hasan H, Zehra A, Riaz L, Riaz R. Insight into the Knowledge, Attitude, Practices, and Barriers Concerning Organ Donation Amongst Undergraduate Students of Pakistan. Cureus. 2019;11:e5517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Puri N. Organ donation must be part of under graduate curriculum in medical education. IJCAP. 2022;9:1-2. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Li MT, Hillyer GC, Husain SA, Mohan S. Cultural barriers to organ donation among Chinese and Korean individuals in the United States: a systematic review. Transpl Int. 2019;32:1001-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Farid MS, Naim Mou TB. Religious, Cultural and Legal Barriers to Organ Donation: The Case of Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Bioethics (BJBio). 2021;12:1-13. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |