Published online Sep 18, 2024. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v14.i3.92981

Revised: May 4, 2024

Accepted: May 23, 2024

Published online: September 18, 2024

Processing time: 167 Days and 11.7 Hours

There is no data evaluating the impact of Medicaid expansion on kidney tran

To investigate the impact of Medicaid expansion on KT patients in Oklahoma.

The UNOS database was utilized to evaluate data pertaining to adult KT reci

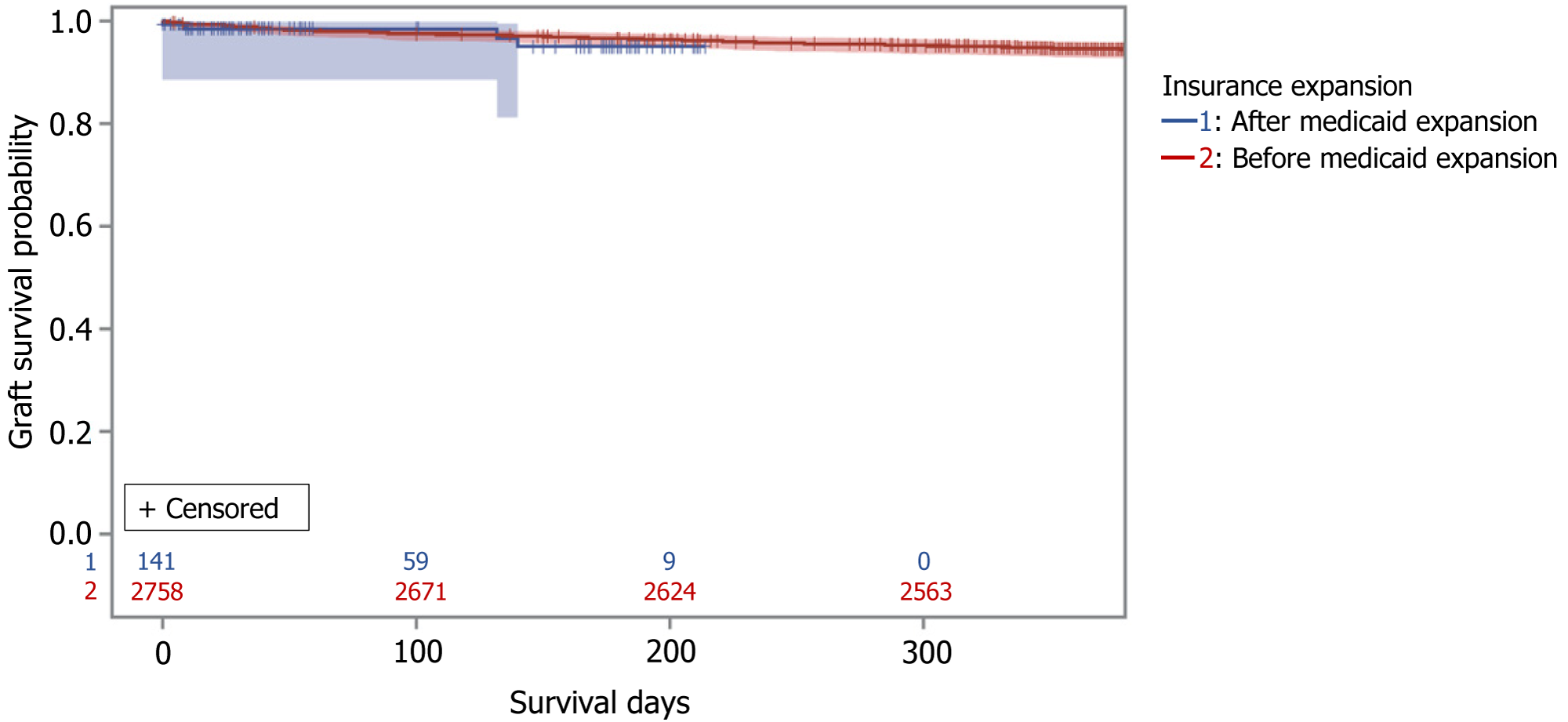

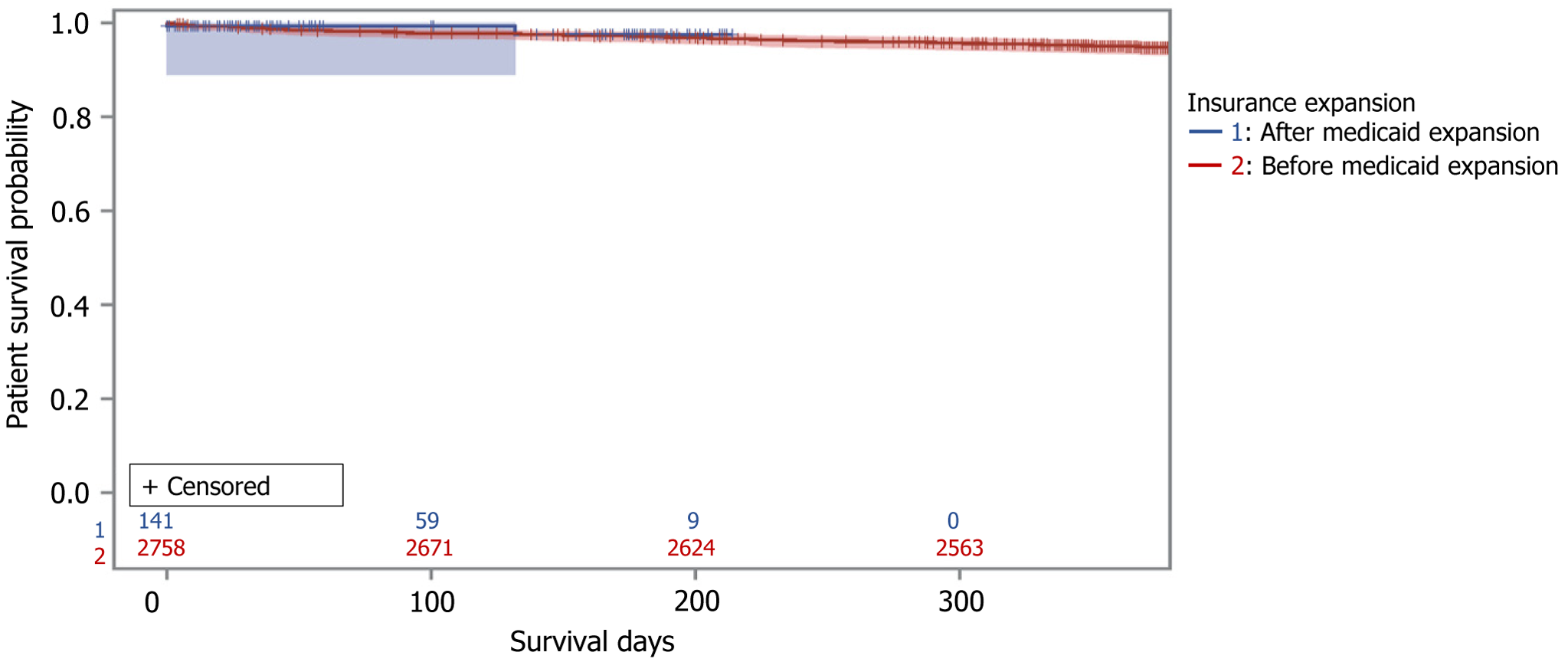

There were 2758 pre- and 141 recipients in the post-Medicaid expansion era. Post-expansion patients were more often non-United States citizens (2.3% vs 5.7%), American Indian, Alaskan, or Pacific Islander (7.8% vs 9.2%), Hispanic (7.4% vs 12.8%), or Asian (2.5% vs 8.5%) (P < 0.0001). Waitlist time was shorter in the post-expansion era (410 vs 253 d) (P = 0.0011). Living donor rates, pre-emptive transplants, re-do transplants, delayed graft function rates, kidney donor profile index values, panel reactive antibodies levels, and insurance types were similar. Patients with public insurance were more frail. Despite increased early (< 6 months) rejection rates, 1-year patient and graft survival were similar. In Cox proportional hazards model, male sex, American Indian, Alaskan or Pacific Islander race, public insurance, and frailty category were independent risk factors for death at 1 year. Medicaid expansion was not associated with graft failure or patient survival (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.07; 95%CI: 0.26-4.41).

Medicaid expansion in Oklahoma is associated with increased KT access for non-White/non-Black and non-United States citizen patients with shorter wait times. 1-year graft and patient survival rates were similar before and after expansion. Medicaid expansion itself was not independently associated with graft or patient survival outcomes. Ongoing research is necessary to determine the long-term effects of Medicaid expansion.

Core Tip: The Medicaid Expansion had a significant impact on several kidney transplant (KT) recipients in Oklahoma. There was greater access to KTs for non-white population (Hispanics, Asians, American Indian, Alaskan, or Pacific Islanders), and Non-United States citizens. Male sex, race, frailty category and insurance type were associated with increased mortality at 1 year after transplant. Medicaid expansion was not associated with 1 year outcomes, however, further research is needed to investigate the long-term impact of Medicaid expansion on Oklahoma.

- Citation: Kwon H, Sandhu Z, Sarwar Z, Andacoglu OM. Impact of Medicaid expansion on kidney transplantation in the State Oklahoma. World J Transplant 2024; 14(3): 92981

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v14/i3/92981.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v14.i3.92981

Health insurance in the United States is a competitive market that includes private and public insurance options. In 2010, the affordable care act (ACA) was introduced by the United States government to achieve the goal of providing more coverage to its citizens, especially those in a lower income bracket. Medicaid is a government program (albeit often administered by private insurance companies that offer Medicaid managed care services). One of the goals of ACA was to expand Medicaid, however expansion of Medicaid has been highly variable among the states. The expansion of Medicaid provided more eligibility to various health care specialties for more individuals and the impact of this expansion has been studied widely[1-5]. The ACA expanded eligibility to include individuals with an income up to 138% of the federal poverty level[1,4]. Based on reported data, the percentage of uninsured adults aged 18-64 decreased from 20.4% to 12.1% from 2013 to 2017[1]. The overall decrease in uninsured adults occurred among all races. Hispanics had the most significant percentage drop of 40.6% to 24.1%, followed by non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic Asians. Furthermore, there was an increase in Medicaid enrollment among end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients with Medicare in the first year after the 21st Century Cures Act, which particularly showed increased enrollment in black, Hispanic, and dual-eligible individuals[3]. In states with Medicaid expansion, there was a significantly higher portion of patients listed with Medicaid than private insurance in transplant surgery[6,7]. This phenomenon is explained as more patients who are previously uninsured and needed transplant surgery became eligible for Medicaid under ACA expansion[8]. Earlier reports suggested an increased number of patients covered by Medicaid with low socioeconomic status may be associated with lower survival rates after solid-organ transplants[9]. Furthermore, there is evolving evidence about the impact of Medicaid expansion on transplant outcomes and increased interest in social-economic determinants that influence not just post-transplant outcomes but also transplant referrals[8,9]. According to studies, similar relationships between patient demographics, such as race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, functionality, kidney function or ESRD, and the health outcome of the KT are shown[9-11]. With more eligibility for Medicaid after the expansion, changing in patient demographic is suspected, which results in a different outcome for Medicaid patients for KT. Furthermore, studies suggest Medicaid expansion affects non-patient changes, such as preemptive waiting list, waitlist time, and others which eventually impact the health outcome of KTs in Medicaid patients[11,12].

Oklahoma only recently passed a Medicaid expansion bill as of 2020[4]. More than 300000 individuals became eligible to enroll for Medicaid beginning on July 1st of 2021 according to Oklahoma Healthcare Agency[4]. There is no published data on the impact of Medicaid expansion in KTs in Oklahoma.

Our aim was to investigate the impact of Medicaid expansion on KT patients in Oklahoma. We specifically investigated: (1) Transplant patients’ demographics before and after expansion; (2) 1-year graft and patient survival rates before and after Medicaid expansion; and (3) investigate the association of Medicaid expansion and other variables with 1-year graft and patient survival.

The Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) and United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) data were used. We compared the recipients with KTs before and after the Medicaid expansion in Oklahoma. We included adults only (> 18 years old), kidney only transplant recipients. We excluded pediatric recipients (< 18 years old), simultaneous transplants with other organs. The evaluated data includes patient demographics, information specific to diseases, graft and patient survival in 1 year follow-up. We included the following variables into our analysis: Citizenship at transplant, recipient age, recipient body mass index (BMI), race, recipient primary payment source at transplant, ESRD diagnosis, history of previous KT (re-do transplant), distance donor hospital to transplant center, deceased donor kidney biopsy, donor kidney glomerulosclerosis %, human leukocyte antigens mismatch level, recipient creatinine at discharge, most recent calculated panel reactive antibodies (PRA), delayed graft function determined by dialysis in first week after transplant, pre-emptive transplant, kidney donor profile index, work for income, calculated estimated post-transplant survival (EPTS), functional status of recipients at registration at transplant, and at follow up, insurance types, organ share types, cold ischemic time (in hours), and waitlist times, rejection within 6 months post-transplant, donor type [live donor, deceased donor, donation after cardiac death (DCD)]. Functional status and frailty were grouped into 3 categories using the Karnofsky performance scale. Group 1 included recipients who could carry on normal activity and work with no special care needed. Group 2 included recipients who were unable to work but able to live at home and care for most personal needs with varying amounts of assistance needed. Group 3 included recipients who were unable to care for themselves and required the equivalent of institutional, or hospital care with rapidly progressing diseases. Insurance was categorized as: Public (Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicaid), Private and Other (self, donation, Freecare and pending). All data were compared between pre-expansion (before July 2021) and post-expansion (after July 2021) eras. The supplemental data were obtained from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention to further compare demographics. University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Research Institutional review board was obtained (No. 15049).

There were 2758 pre- and 141 post-Medicaid expansion adult KT recipients. Compared to pre-expansion patients, there were more non-United States citizen patients (2.3% vs 5.7%, P = 0.0188) with a significant increase in Hispanic (7.4% vs 12.8%), Asian (2.5% vs 8.5%) and American Indian, Alaskan, or Pacific Islanders population (7.8% vs 9.2%, P < 0.0001). There were no significant differences in median age, gender distribution, or median BMI between pre- and post-Medicaid expansion recipients (Table 1). There were more patients with EPTS > 20% in the post-expansion era (24.4% vs 56.7%, P < 0.0001). Functional status at transplant and at the most recent follow-up was similar between pre-and post-expansion recipients. More regional (3.7% vs 17.0%) and national (8% vs 34.8%) organ sharing was observed with resultant longer cold ischemic time (12 vs 16 h) (all P < 0.0001). Wait time was shorter in the post-expansion era (410 vs 253 d, P = 0.0011). Living donor rates, DCD grafts, history of previous KTs, pre-emptive transplant, delayed graft function rates, kidney donor profile index values, and PRA levels were all similar between the pre- and post-expansion era (Table 1). Although there was less public insurance in the post-expansion era, (69.7% vs 66.7%) this was statistically not significant (P > 0.05) (Table 1). Despite increased early (< 6 months) rejection rates, 1-year graft (94.6% vs 97.2%) and patient survival rates (95% vs 98.6%) were similar before and after Medicaid expansion, respectively (Figures 1 and 2).

| Variables | Before medicaid expansion | After medicaid expansion | P value |

| Recipient age, median (IQR) | 53.0 (21.0) | 51.0 (22.0) | 0.3999c |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1089 (39.5) | 56 (39.7) | 0.9563 |

| Male | 1669 (60.5) | 85 (60.3) | |

| Recipient BMI, Median (IQR) | 27.8 (7.6) | 28.4 (8.0) | 0.1549c |

| Race | |||

| White | 1708 (61.9) | 75 (53.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Black | 531 (19.3) | 22 (15.6) | |

| Amer Ind/Alaska Native/Pacific Islander | 215 (7.8) | 13 (9.2) | |

| Hispanic | 204 (7.4) | 18 (12.8) | |

| Asian | 68 (2.5) | 12 (8.5) | |

| Multiracial | 32 (1.2) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Citizenship at transplant | |||

| United States citizen | 2696 (97.8) | 133 (94.3) | 0.0188a |

| Non-United States citizen | 62 (2.3) | 8 (5.7) | |

| ESRD diagnosis | |||

| Other | 1423 (51.8) | 85 (60.3) | 0.0646 |

| Diabetes | 778 (28.3) | 26 (18.4) | |

| Hypertension | 546 (19.9) | 30 (21.3) | |

| History of a previous kidney transplant | 306 (11.1) | 14 (9.9) | 0.6665 |

| Recipient pretransplant dialysis | 2303 (83.9) | 110 (78.0) | 0.0673 |

| Initial calculated EPTS | |||

| < 20% | 2086 (75.6) | 61 (43.3) | < 0.0001 |

| ≥ 20% | 672 (24.4) | 80 (56.7) | |

| PRA, median (IQR) | 0.0 (27.0) | 0.0 (37.0) | 0.3133c |

| Recipient functional status at transplant | |||

| Able to carry on normal activity and to work. No special care needed | 2158 (80.6) | 11 (80.9) | 0.5848 |

| Unable to work; able to live at home and care for most personal needs; varying amount of assistance needed | 499 (18.6) | 27 (19.2) | |

| Unable to care for self; requires equivalent of institutional or hospital care; diseases may be progressing rapidly | 20 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Recipient functional status-most recent at follow-up | |||

| Able to carry on normal activity and to work. No special care needed | 1025 (80.8) | 116 (82.3) | 0.1781 |

| Unable to work; able to live at home and care for most personal needs; varying amount of assistance needed | 197 (15.5) | 24 (17.0) | |

| Unable to care for self; requires equivalent of institutional or hospital care; diseases may be progressing rapidly | 46 (3.6) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Total days on waiting list/including inactive time, median (IQR) | 410.0 (683.0) | 253.0 (621.0) | 0.0011c |

| Donor type | |||

| Deceased donor | 2098 (76.1) | 111 (78.7) | 0.4705 |

| Living donor | 660 (23.9) | 30 (21.3) | |

| DCD donor | 469 (22.4) | 33 (29.7) | 0.0708 |

| Deceased donor kidney biopsy | 681 (32.5) | 46 (41.4) | 0.0497 |

| Donor kidney glomerulosclerosis, % | |||

| ≤ 20 | 709 (98.6) | 52 (100.0) | 1.0000a |

| > 20 | 10 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| HLA mismatch level | |||

| 0 | 199 (7.2) | 9 (6.4) | 0.0161 |

| 1 | 70 (2.5) | 1 (0.7) | |

| 2 | 203 (7.4) | 7 (5.0) | |

| 3 | 439 (16.0) | 21 (15.0) | |

| 4 | 678 (24.7) | 54 (38.6) | |

| 5 | 800 (29.1) | 31 (22.1) | |

| 6 | 362 (13.2) | 17 (12.1) | |

| Delayed graft function | 408 (14.8) | 27 (19.2) | 0.1578 |

| KDPI | |||

| Low < 20% | 648 (31.0) | 40 (36.0) | 0.4063 |

| Moderate 20%-85% | 1375 (65.7) | 69 (62.2) | |

| High > 85% | 69 (3.3) | 2 (1.8) | |

| KDPI, median (IQR) | 34.0 (40.0) | 34.0 (50.0) | 0.9930c |

| Share type | |||

| Local | 2437 (88.4) | 68 (48.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Regional | 101 (3.7) | 24 (17.0) | |

| National | 220 (8.0) | 49 (34.8) | |

| Kidney cold ischemic time (hours), median (IQR) | 12.0 (12.5) | 16.0 (12.9) | < 0.0001c |

| Rejection within 6 months | 176 (7.5) | 9 (16.4) | 0.0344a |

| Post TX | |||

| Recipient primary insurance at transplant | |||

| Private insurance | 835 (30.3) | 47 (33.3) | 0.5142b |

| Public insurance | 1921 (69.7) | 94 (66.7) | |

| Other | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Working for income | 876 (34.7) | 57 (42.2) | 0.0752 |

We also evaluated frailty, and insurance among race groups. Non-white groups had public insurance more commonly (P = 0.0003). Although frailty scores were similar among racial categories, patients with public insurance had significantly worse frailty scores (P = 0.0003) (Tables 2-4). Cox proportional hazards model was performed and after controlling for other variables male sex [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR): 1.186, 95%CI: 1.01-1.40], American Indian/Alaska Native/Pacific Islanders race (aHR: 1.521, 95%CI: 1.18-1.97), public insurance (aHR: 1.536, 95%CI: 1.25-1.88), and frailty category (aHR: 2.134, 95%CI: 1.09-4.20) were independent risk factors for mortality at 1 year after transplant. Medicaid expansion itself was not associated with higher risk of graft failure or patient survival (aHR: 1.07; 95%CI: 0.26-4.41) (Table 5).

| Functional status at transplant | Private insurance (%) | Public insurance (%) | Other (%) | P value |

| Able to carry on normal activity and to work. No special care needed | 1083 (86.4) | 1184 (75.9) | 5 (100.0) | 0.0003b |

| Unable to work; able to live at home and care for most personal needs; varying amount of assistance needed | 168 (13.4) | 358 (23.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unable to care for self; requires equivalent of institutional or hospital care; diseases may be progressing rapidly | 2 (0.2) | 18 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Insurance | White 1783 (61.6) | Black 553 (19.1) | AI/NH/PI (0.08) | Hispanic (0.08) | Asian (0.03) | Multiracial (0.01) | P value |

| Private insurance | 905 (50.8) | 181 (32.7) | 91 (39.9) | 80 (36.0) | 35 (43.8) | 7 (21.2) | 0.0003 |

| Public insurance | 874 (49.0) | 371(67.1) | 137 (60.1) | 142 (64.0) | 45 (56.3) | 26 (78.8) | |

| Other | 4 (0.22) | 1 (0.18) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| Recipient functional status transplant | White 1783 (61.6) | Black 553 (19.1) | AI/NH/PI (0.08) | Hispanic (0.08) | Asian (0.03) | Multiracial (0.01) | P value |

| Able to carry on normal activity and to work. No special care needed | 1391 (80.5) | 435 (79.7) | 178 (81.3) | 178 (81.7) | 65 (85.5) | 25 (78.1) | 0.8401b |

| Unable to work; able to live at home and care for most personal needs; varying amount of assistance needed | 322 (18.7) | 108 (19.8) | 40 (18.3) | 39 (17.9) | 11 (14.5) | 6 (18.8) | |

| Unable to care for self; requires equivalent of institutional or hospital care; diseases may be progressing rapidly | 14 (0.81) | 3 (0.55) | 1 (0.46) | 1 (0.46) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (3.1) |

| Variables | aHR (95%CI) | P value |

| Age | 1.04 (1.03, 1.05) | < 0.0001 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | Reference | |

| Male | 1.19 (1.01, 1.40) | 0.0426 |

| Race | ||

| White | Reference | |

| Black | 0.98 (0.87, 1.20) | 0.8699 |

| Amer Ind/Alaska Native/Pacific Islander | 1.52 (1.18, 1.97) | 0.0014 |

| Hispanic | 0.82 (0.58, 1.17) | 0.2748 |

| Asian | 0.73 (0.40, 1.33) | 0.3056 |

| Multiracial | 1.05 (0.34, 3.32) | 0.9289 |

| Insurance | ||

| Private insurance | Reference | |

| Public insurance | 1.54 (1.25, 1.88) | < 0.0001 |

| Recipient functional status at transplant | ||

| Able to carry on normal activity and to work. No special care needed | Reference | |

| Unable to work; able to live at home and care for most personal needs; varying amount of assistance needed | 1.53 (1.27, 1.84) | < 0.0001 |

| Unable to care for self; requires equivalent of institutional or hospital care; diseases may be progressing rapidly | 2.13 (1.09, 4.20) | 0.0281 |

| Medicaid expansion | ||

| Before medicaid expansion | Reference | |

| After medicaid expansion | 1.07 (0.26, 4.41) | 0.9290 |

This is the first report analyzing the impact of the Medicaid expansion on KT in Oklahoma after it was implemented in 2021. This is also the first report analyzing the impact of Medicaid expansion on the American Indian population after KT. We report several important findings: We report that an increased number of patients from underrepresented minorities received KTs after the Medicaid expansion. Non-United States citizens, American Indian, Alaskan and Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and Asian recipients received more KTs in the post-expansion era. Similar findings are reported in other studies. Harhay et al[12] reported that more low-income United States patients with chronic kidney disease received KT before requiring dialysis after Medicaid expansion. Harhay et al[12] also reported that pre-emptive KT recipients from expansion states were more likely to be from minority groups. The OPTN/SRTR 2021 Annual report found that the proportion of Asian and Hispanic candidates on the kidney waiting list has gradually increased, accompanied by a decline in the proportion of White candidates[13].

We also report that waitlist times decreased after Medicaid expansion in Oklahoma. Several other studies also reported similar results. OPTN/SRTR 2020 Annual Kidney Report shows that patients waiting less than 1 year comprise most of the waitlist KT candidates. On the other hand, 10% of the patients have been waiting for more than 5 years[14]. The 2021 Annual Kidney Report found that the proportion of candidates prevalent on the waiting list with waiting time less than 1 year rose to 34.2% in 2021 from 31.4% in 2020 and 33.9% in 2019, while 13.6% on the waiting list at some point in 2021 have been waiting 5 years or longer, a proportion that has been decreasing in recent years[13]. The decrease in waitlists nationally is a result of allocation policy changes, but also could be affected by Medicaid expansion as well, for instance higher priority patients may be getting more access to transplant because of expansion. Although, in our study, PRA levels and re-do transplant rates were similar before and after expansion. Findings may change in the longer-term follow-up.

We analyzed frailty scores among different racial and insurance groups. In our report, frailty scores were similar in pre- and post- Medicaid expansion eras and among different racial groups; however, frailty and public insurance were associated with worse outcomes in Oklahoma. Dubay et al[9] also found that in renal transplant patients, public insurance was associated with a 1.4% lower survival rate, and Medicaid itself was associated with a higher mortality hazard ratio when compared to private insurance. Frailty is an important status when evaluating patients for transplant. Frailty is associated with reduced access to the waiting list and higher waiting list mortality[15]. In a study of 7078 individuals who were evaluated at three transplant centers between 2009 and 2018, frail individuals were almost half as likely as non-frail individuals to be placed on a KT waiting list[16]. Pérez-Sáez et al[17] also found that in KT candidates, pre-frailty and frailty according to both the PFP and the FRAIL scale were associated with poorer results while listed. While it is critical to improve access to transplant for all patient groups including frail patients, ongoing strategies are necessary to improve outcomes in this patient population.

We also report that several independent risk factors that were associated with worse graft and patient outcomes at 1 year in the post-Medicaid expansion era such as male sex and race, specifically American Indian, Alaskan, or Pacific Islander group. These results differ from other studies. Seipp et al[18] analyzed the KT outcomes for indigenous patients in the United States and found that cardiovascular, graft and infectious outcomes were similar between white and American Indian groups. While the impact of sex in KT outcomes is not consistent, in some studies it is suggested that the male sex is considered an independent factor for poor survival outcomes after KT[19]. Increased long term mortality after KT is observed in Native Americans when no confounders are adjusted[20]. We were not able to analyze specific variables per racial groups in our study due to sample size.

We report that 1-year patient and graft survival rates were similar in the pre- and post-Medicaid expansion eras, despite increased early rejection rates. Other studies show worse outcomes for Medicaid patients. Medicaid organ transplant beneficiaries had significantly lower survival compared with privately insured beneficiaries[21]. The more severe organ failure among Medicaid beneficiaries at the time of listing suggested a pattern of late referral, which might account for worse outcomes[9]. A higher portion of patients with low socioeconomic factors received transplants through Medicaid. Social factors such as social, race, and education levels can play a role in determining transplantation outcomes and individuals with low socioeconomic factors were found to be associated with worse health care outcomes overall[22-24].

Lastly, we found that 1-year patient and graft survival were similar in the pre- and post-Medicaid expansion eras. This contrasts with other studies that reported better or worse survival for the Medicaid population[9,25,26]. Trivedi et al[6] found that states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA had a significant increase in the proportion of patients listed with Medicaid and better 1-year waiting list survival. That highlights the need for further long-term studies.

Our limitations include: (1) Study only reflects short-term follow-up since Medicaid expansion as it was only recently implemented in Oklahoma; and (2) we had a relatively small sample size in the post expansion era due to the aforementioned limitation. Therefore, to address the true impact of this expansion, further research is needed to fully understand the long-term impact of Medicaid expansion on KT outcomes, as well as the potential challenges that may arise as more patients become eligible for transplantation services. Although this research didn’t analyze global data, the preliminary results in this study imply that access to healthcare for underrepresented minorities leads to more KTs. Further research would be needed to analyze the global impact of Medicaid or affordable healthcare.

The Medicaid Expansion had a significant impact on KT recipients in Oklahoma: (1) More access to KT for non-United States citizens, and non-white population (Hispanics, Asians, American Indian, Alaskan, or Pacific Islander); (2) there were shorter waitlist times for patients regardless of distance and local sharing; (3) similar 1-year graft and patient survival in pre and post-expansion eras; (4) Medicaid expansion itself is not associated with one-year outcomes; and (5) male sex, American Indian/Alaska Native/Pacific Islanders race, public insurance and frailty category are risk factors for mortality at 1 year after transplant in Oklahoma. Further research is necessary to investigate the long-term impact of the Medicaid expansion on adult KT patients in Oklahoma.

| 1. | Cohen RA, Martinez ME, Zammitti EP. Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, January-March 2017. 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201708.pdf. |

| 2. | Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The Effects Of Medicaid Expansion Under The ACA: A Systematic Review. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37:944-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nguyen KH, Oh EG, Meyers DJ, Kim D, Mehrotra R, Trivedi AN. Medicare Advantage Enrollment Among Beneficiaries With End-Stage Renal Disease in the First Year of the 21st Century Cures Act. JAMA. 2023;329:810-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | OKLAHOMA. Medicaid Expansion. Available from: https://www.oklahoma.gov/ohca/about/medicaid-expansion/expansion.html. |

| 5. | Yue D, Rasmussen PW, Ponce NA. Racial/Ethnic Differential Effects of Medicaid Expansion on Health Care Access. Health Serv Res. 2018;53:3640-3656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Trivedi JR, Ising M, Fox MP, Cannon RM, van Berkel VH, Slaughter MS. Solid-Organ Transplantation and the Affordable Care Act: Accessibility and Outcomes. Am Surg. 2018;84:1894-1899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Harhay MN, McKenna RM, Boyle SM, Ranganna K, Mizrahi LL, Guy S, Malat GE, Xiao G, Reich DJ, Harhay MO. Association between Medicaid Expansion under the Affordable Care Act and Preemptive Listings for Kidney Transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:1069-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Oliveira GH, Al-Kindi SG, Simon DI. Implementation of the Affordable Care Act and Solid-Organ Transplantation Listings in the United States. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:737-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | DuBay DA, MacLennan PA, Reed RD, Shelton BA, Redden DT, Fouad M, Martin MY, Gray SH, White JA, Eckhoff DE, Locke JE. Insurance Type and Solid Organ Transplantation Outcomes: A Historical Perspective on How Medicaid Expansion Might Impact Transplantation Outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223:611-620.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Patzer RE, Pastan SO. Kidney transplant access in the Southeast: view from the bottom. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:1499-1505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Goyal N, Weiner DE. The Affordable Care Act, Kidney Transplant Access, and Kidney Disease Care in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:982-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Harhay MN, McKenna RM, Harhay MO. Association Between Medicaid Expansion Under the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid-Covered Pre-emptive Kidney Transplantation. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2322-2325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lentine KL, Smith JM, Miller JM, Bradbrook K, Larkin L, Weiss S, Handarova DK, Temple K, Israni AK, Snyder JJ. OPTN/SRTR 2021 Annual Data Report: Kidney. Am J Transplant. 2023;23:S21-S120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lentine KL, Smith JM, Hart A, Miller J, Skeans MA, Larkin L, Robinson A, Gauntt K, Israni AK, Hirose R, Snyder JJ. OPTN/SRTR 2020 Annual Data Report: Kidney. Am J Transplant. 2022;22 Suppl 2:21-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 76.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cheng XS, Lentine KL, Koraishy FM, Myers J, Tan JC. Implications of Frailty for Peritransplant Outcomes in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Curr Transplant Rep. 2019;6:16-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Harhay MN, Rao MK, Woodside KJ, Johansen KL, Lentine KL, Tullius SG, Parsons RF, Alhamad T, Berger J, Cheng XS, Lappin J, Lynch R, Parajuli S, Tan JC, Segev DL, Kaplan B, Kobashigawa J, Dadhania DM, McAdams-DeMarco MA. An overview of frailty in kidney transplantation: measurement, management and future considerations. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:1099-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pérez-Sáez MJ, Redondo-Pachón D, Arias-Cabrales CE, Faura A, Bach A, Buxeda A, Burballa C, Junyent E, Crespo M, Marco E, Rodríguez-Mañas L, Pascual J. Outcomes of Frail Patients While Waiting for Kidney Transplantation: Differences between Physical Frailty Phenotype and FRAIL Scale. J Clin Med. 2022;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Seipp R, Zhang N, Nair SS, Khamash H, Sharma A, Leischow S, Heilman R, Keddis MT. Patient and allograft outcomes after kidney transplant for the Indigenous patients in the United States. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0244492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen PD, Tsai MK, Lee CY, Yang CY, Hu RH, Lee PH, Lai HS. Gender differences in renal transplant graft survival. J Formos Med Assoc. 2013;112:783-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wiley HR. Kidney Transplant Outcomes in Indigenous People of the Northern Great Plains of the United States. S D Med. 2022;75:460. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Katz-Greenberg G, Samoylova ML, Shaw BI, Peskoe S, Mohottige D, Boulware LE, Wang V, McElroy LM. Association of the Affordable Care Act on Access to and Outcomes After Kidney or Liver Transplant: A Transplant Registry Study. Transplant Proc. 2023;55:56-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kurella-Tamura M, Goldstein BA, Hall YN, Mitani AA, Winkelmayer WC. State medicaid coverage, ESRD incidence, and access to care. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:1321-1329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wesselman H, Ford CG, Leyva Y, Li X, Chang CH, Dew MA, Kendall K, Croswell E, Pleis JR, Ng YH, Unruh ML, Shapiro R, Myaskovsky L. Social Determinants of Health and Race Disparities in Kidney Transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16:262-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Johnson WR, Rega SA, Feurer ID, Karp SJ. Associations between social determinants of health and abdominal solid organ transplant wait-lists in the United States. Clin Transplant. 2022;36:e14784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, Bernstein M, Gruber JH, Newhouse JP, Schneider EC, Wright BJ, Zaslavsky AM, Finkelstein AN; Oregon Health Study Group. The Oregon experiment--effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1713-1722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 723] [Cited by in RCA: 647] [Article Influence: 53.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kao J, Reid N, Hubbard RE, Homes R, Hanjani LS, Pearson E, Logan B, King S, Fox S, Gordon EH. Frailty and solid-organ transplant candidates: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22:864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |