Published online Sep 18, 2024. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v14.i3.91214

Revised: April 30, 2024

Accepted: May 28, 2024

Published online: September 18, 2024

Processing time: 214 Days and 10.2 Hours

Famure et al describe that close to 50% of their patients needed early or very early hospital readmissions after their kidney transplantation. As they taught us the variables related to those outcomes, we describe eight teaching capsules that may go beyond what they describe in their article. First two capsules talk about the ideal donors and recipients we should choose for avoiding the risk of an early readmission. The third and fourth capsules tell us about the reality of cadaveric donors and recipients with comorbidities, and the way transplant physicians should choose them to maximize survival. Fifth capsule shows that any mistake can result in an early readmission, and thus, in poorer outcomes. Sixth capsule talks about economic losses of early readmissions, cost-effectiveness of tran

Core Tip: Famure et al describe that approximately 50% of their patients needed early or very early hospital readmissions after their kidney transplantation, which was related to poorer outcomes and more expensive treatments. While the ideal scenario of a kidney transplant is not achievable, transplant physicians must know their risk profile to build their patient-portfolio in order to maximize outcomes and minimize costs and maintain transplantation cost-effectiveness.

- Citation: Gonzalez FM, Gonzalez Cohens FDR. Kidney transplantation outcomes: Is it possible to improve when good results are falling down? World J Transplant 2024; 14(3): 91214

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v14/i3/91214.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v14.i3.91214

At first glance, a manuscript dedicated to describe outcomes after kidney transplantation may seem trivial, because it would show a series of numbers intending to highlight the pros- and cons- of being transplanted, in this case, in a single center in Canada. Nevertheless, Famure et al[1] did a great job teaching us far more than those numbers. Let us begin.

With a casuistic of nearly 200 transplants per year between 2009 and 2017, they describe that 22.4% of their kidney recipients needed a very early hospital readmission (VEHR) (≤ 30 d), and 29.6% an early hospital readmission (EHR) (≤ 90 d). Interestingly, both types of readmissions are not alike at all. In summary, VEHR responds more often to what happens in the early post-transplant period: Expanded criteria donor and presumably delayed graft function, and acute rejection episodes. The characteristics of those patients who needed an EHR, on the other hand, were being older, suffering from a significant comorbidity, such as diabetes or dialysis vintage, received a graft from an older donor, or suffered an acute rejection episode. But Famure et al’s teachings go beyond these. In fact, we divided them into 8 teaching capsules that we will expand in the following paragraphs[1].

First teaching capsule: To avoid VEHR, try to prefer young living donors, or standard criteria cadaveric donors, and an immunologically low risk recipient. An illustrative example could be Johanna Nightingale, who received a kidney from her identical twin in 1960 when she was 12 years old, and carried a completely normal life afterwards for at least five decades[2].

Second teaching capsule: To avoid EHR, try choosing recipients who are young, healthy, and with a short stay, or even without a stay, on dialysis. Even more, use a young and well-matched donor. Johanna Nightingale could, of course, fit the requirements once again.

Third teaching capsule: As you may think, the two previous capsules are ideal scenarios that are rare to find. In fact, “life is hard”, and most kidney grafts come from old, non-trauma brain dead, and non-healthy donors. Indeed, several come from extended criteria donors, and are later implanted in not young and not low immunologically risky recipients. Moreover, most recipients live in countries with low organ procurement rates, face long stays in dialysis as a con

Fourth teaching capsule: Under the conditions mentioned above, kidney transplant centers face the situation of looking for, identifying, and procuring the best quality organ donors as possible, and matching their graft’s kidney donor profile index (KDPI)[4,5] with some prognostic factors correlated with better graft survival in recipients[6]. A better approach could be to match prognostic characteristics of donor/graft with other factors present in recipients in order to maximize both graft and patient survivals[7].

Fifth teaching capsule: Anything that goes wrong brings adverse consequences. Both VEHR and EHR (something that went wrong) predict later hospitalizations (adverse consequences), jeopardizing graft survival and long term recipient survival.

Sixth teaching capsule: If the transplanted patient has any complication, the global clinical care will be more expensive. In this regard, Famure et al[1] manuscript shows in their figure 2, that the first month’s cost of those patients who needed a VEHR was more than two times the cost of uncomplicated patients. Moreover, the slopes of the total cost functions of VEHR and non-VEHR diverge in time, implicating that a VEHR is an ominous sign for the transplant program budget.

One of the questions that emerges from this issue is: Is it cost-effective to transplant a patient that will have a VEHR or EHR? We know that transplantation is the cost-effective treatment alternative to dialysis[8], but if the patient presents a VEHR or EHR, is it still cost-effective?

Certainly, to answer this question, a formal cost-effectiveness analysis should be done. But we can, based on a study also done in Canada, pose the hypothesis that kidney transplantation will still be cost-effective for patients presenting an EHR. In this study, the researchers found that despite the cost group where each patient belonged to (low-, medium-, or high-cost) before accessing their transplant, they all held cost reductions in their treatments after transplantation. Surprisingly, the high-cost group held the largest savings[9].

If we consider that patients who have an EHR were medium- or high-cost patients before accessing their transplants, and that previous findings are applicable, we should expect those patients to still be cost-effective. Nonetheless, for patients who present a VEHR it is a little bit more complicated because, as we mentioned before, VEHR is related to the donor conditions, so cost-effectiveness is still unclear, which is aligned with findings in the literature[8].

Could it be possible to improve the clinical and economic results of a transplant program like the one described by Famure et al[7]? Of course it is, but the solution can be problematic. Because at first glance it would be obligatory to discriminate between potential organ recipients, choosing those with lower risk as described in the manuscript: Young, without any significant comorbidity, with a short history of dialysis, and with an optimal HLA. As this behavior is not sustainable it is necessary to look for other alternatives.

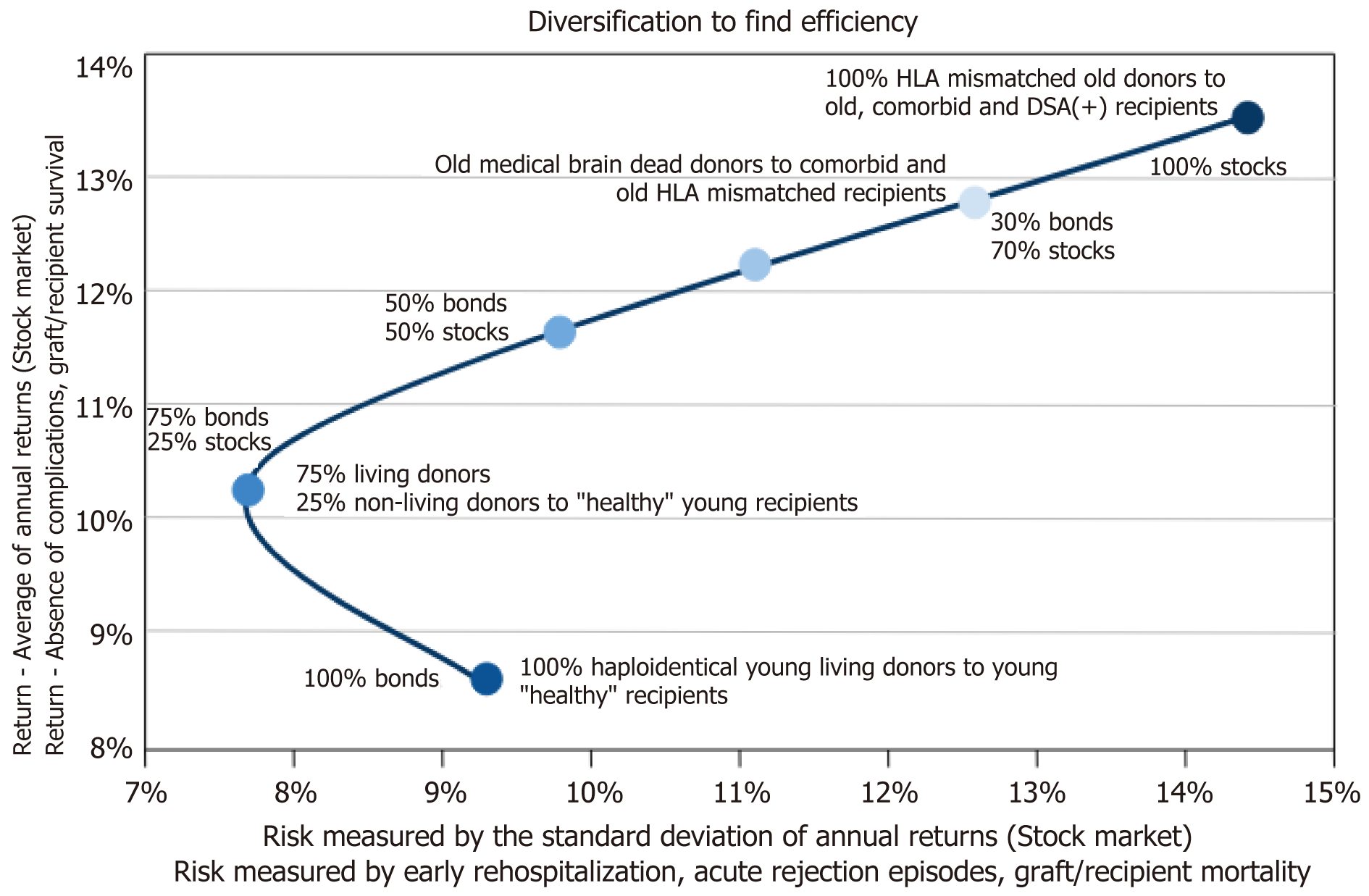

In 1990, Harry Markowitz won the Nobel Prize for Economic Sciences with his Portfolio Theory[10]. It is an investment theory based on the idea that risk-averse investors, like transplant physicians, can construct portfolios (combination of bonus and stocks) to optimize or maximize the expected return based on a given level of market risk. This emphasizes that risk is an inherent part of a higher reward. In both finances and transplant medicine, the “investor” will choose the least risky alternative, and the transplant physician will try to combine donor, grafts, and recipient characteristics in order to maximize clinical results with the lowest total cost (humane and financial) and without sacrificing equity (Figure 1)[11].

Wise clinicians, like transplants physicians, can construct adequate donor and recipient pairs to maximize “good” results, minimizing risks with an unconscious internal Bayes theorem in their minds. For example, with strategies like “old for old”[12] or by skipping the waiting list priority trying to improve recipients´ estimated post-transplant survival[13].

Seventh teaching capsule: If you know your “numbers”, you can try to improve them with something similar to portfolio management.

The last two interesting findings of Famure et al[1] are that total EHR results are comparable to United States hospitals, and that the later cohort (2015-2017) did worse than the previous one, both in VEHR and EHR. This last finding is counterintuitive if we consider transplant physicians’ learning curve. It is possible that transplant physicians behave less risk averse in some point of their career than in its beginning, as it happens to some inversionist that prefer portfolios rich in stocks as they gain expertise (Figure 1).

Eighth teaching capsule: Kidney transplant figures are much the same in centers where transplant physicians are experts or, at least, share enough expertise to transform this activity into a “commodity”. If the donor, graft, and recipient are average or average plus one-to-two standard deviations, the results will be similar in comparable centers. But, if any of them are outliers of their respective distributions, it is advisable to perform the kidney transplantation in a very specialized institution.

As a corollary, the kidney transplantation macro-process has four subprocesses: (1) Wait listed end stage renal disease patients with a proper medical study to diagnose and compensate chronic comorbid diseases with the theoretical aim that the kidney disease is the only relevant medical condition to be considered; (2) Selection of living donors without any kidney disease, or procuring a non-living donor with no significant chronic or acute kidney disease with the objective that the transplanted glomerular filtration rate is > 50% of the theoretical rate; (3) Allocation of the donated kidney to the most appropriate candidate, matching immunological, clinical, and other significant variables potentially related to outcomes; (4) Adequate global surgical and medical care post transplantation to enhance short- and long-term graft and recipient survival. Main protagonists of this macro-process are physicians like those of Famure’s team in Toronto, Canada[1].

Finally, the evolution of the epidemiology in kidney transplant candidates poses extra challenges that transplant clinicians and public health practitioners should not ignore. Famure et al[1] highlight that in their article, and propose the prevention of EHR and VEHR as a central pillar, where a multidisciplinary approach is needed to succeed.

| 1. | Famure O, Kim ED, Li Y, Huang JW, Zyla R, Au M, Chen PX, Sultan H, Ashwin M, Minkovich M, Kim SJ. Outcomes of early hospital readmission after kidney transplantation: Perspectives from a Canadian transplant centre. World J Transplant. 2023;13:357-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (39)] |

| 2. | Tullius SG, Rudolf JA, Malek SK. Moving boundaries--the Nightingale twins and transplantation science. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1564-1565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Miskulin D, Bragg-Gresham J, Gillespie BW, Tentori F, Pisoni RL, Tighiouart H, Levey AS, Port FK. Key comorbid conditions that are predictive of survival among hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1818-1826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Port FK, Bragg-Gresham JL, Metzger RA, Dykstra DM, Gillespie BW, Young EW, Delmonico FL, Wynn JJ, Merion RM, Wolfe RA, Held PJ. Donor characteristics associated with reduced graft survival: an approach to expanding the pool of kidney donors. Transplantation. 2002;74:1281-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 614] [Cited by in RCA: 629] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dahmen M, Becker F, Pavenstädt H, Suwelack B, Schütte-Nütgen K, Reuter S. Validation of the Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) to assess a deceased donor's kidneys' outcome in a European cohort. Sci Rep. 2019;9:11234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lentine KL, Smith JM, Hart A, Miller J, Skeans MA, Larkin L, Robinson A, Gauntt K, Israni AK, Hirose R, Snyder JJ. OPTN/SRTR 2020 Annual Data Report: Kidney. Am J Transplant. 2022;22 Suppl 2:21-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 76.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Coca A, Arias-Cabrales C, Valencia AL, Burballa C, Bustamante-Munguira J, Redondo-Pachón D, Acosta-Ochoa I, Crespo M, Bustamante J, Mendiluce A, Pascual J, Pérez-Saéz MJ. Validation of a survival benefit estimator tool in a cohort of European kidney transplant recipients. Sci Rep. 2020;10:17109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fu R, Sekercioglu N, Berta W, Coyte PC. Cost-effectiveness of Deceased-donor Renal Transplant Versus Dialysis to Treat End-stage Renal Disease: A Systematic Review. Transplant Direct. 2020;6:e522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Koto P, Tennankore K, Vinson A, Krmpotic K, Weiss MJ, Theriault C, Beed S. What are the short-term annual cost savings associated with kidney transplantation? Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2022;20:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Markowitz HM. Foundations of Portfolio Theory. Nobel Lecture. December 7, 1990. Available from: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/markowitz-lecture.pdf. |

| 11. | Sharma A. Build a Portfolio of Cryptocurrencies using Modern Portfolio Theory. Medium.com, December 2, 2017. Available from: https://asankhaya.medium.com/build-a-portfolio-of-cryptocurrencies-using-modern-portfolio-theory-d65217858660. |

| 12. | Arns W, Citterio F, Campistol JM. 'Old-for-old'--new strategies for renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:336-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | King KL, Husain SA, Yu M, Adler JT, Schold J, Mohan S. Characterization of Transplant Center Decisions to Allocate Kidneys to Candidates With Lower Waiting List Priority. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2316936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |