Published online Sep 18, 2024. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v14.i3.90949

Revised: May 2, 2024

Accepted: June 7, 2024

Published online: September 18, 2024

Processing time: 225 Days and 21 Hours

Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) in combination with a potent nucleos(t)ide analog is considered the standard of care for prophylaxis against hepatitis B virus (HBV) reinfection after liver transplantation for HBV-associated disease.

To evaluate patients’ satisfaction, preferences, and requirements for subcutaneous (SC), intramuscular (IM), and intravenous (IV) HBIG treatments.

A self-completion, cross-sectional, online, 22-question survey was conducted to examine perceptions and satisfaction with current HBIG treatment in adults receiving HBIG treatment following liver transplantation for HBV-associated disease in France, Italy, and Turkey. Hypothetical HBIG products with different administration modes were evaluated using target product profile assessment and a conjoint (trade-off) exercise.

Ninety patients were enrolled; 32%, 17%, and 51% were SC, IM, and IV HBIG users, respectively. Mean duration of treatment was 36.2 months. SC HBIG had the least negative impact on emotional well-being and social life and was perceived as the most convenient, easiest to administer, least painful, and had the highest self-rating of treatment compliance. More IM HBIG users than SC or IV HBIG users reported that administration frequency was excessive (67%, 28%, and 28%, respectively). In the target product profile assessment, 76% of patients were likely to use hypothetical SC HBIG. In the conjoint exercise, administration route, frequency, and duration were key drivers of treatment preferences.

Ease, frequency, duration, and side effects of HBIG treatment administration were key drivers of treatment preferences, and SC HBIG appeared advantageous over IM and IV HBIG for administration ease, convenience, and pain. A hypothetical SC HBIG product elicited a favorable response. Patient demographics, personal preferences, and satisfaction with HBIG treatment modalities may influence long-term treatment compliance.

Core Tip: Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) combined with a potent nucleos(t)ide analog is recommended in patients undergoing liver transplantation for hepatitis B virus-associated disease. A survey was conducted to determine patients’ thoughts about three forms of HBIG treatment administration - subcutaneous (SC), intramuscular, and intravenous. Regarding current treatment, SC HBIG had the least negative impact on emotional well-being and social life, was most convenient, easiest to administer and least painful. Considering hypothetical HBIG products, SC was preferred over intramuscular and intravenous for ease of administration, convenience, and pain. For these patients, the most important considerations were ease of use, frequency, duration, and side effects.

- Citation: Rizza G, Glynou K, Eletskaya M. Impact of hepatitis B immunoglobulin mode of administration on treatment experiences of patients after liver transplantation: Results from an online survey. World J Transplant 2024; 14(3): 90949

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v14/i3/90949.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v14.i3.90949

Survival outcomes for liver transplant recipients have increased markedly in recent years owing to advances in surgical techniques and immunosuppressive therapy, and improved management of postsurgical complications[1]. While liver transplantation is indicated in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and decompensated cirrhosis[2,3], graft reinfection with HBV could result in liver damage, graft failure or patient death[4,5]. For patients who have received liver transplantation for HBV-associated disease, international guidelines recommend a combination of a potent nucleos(t)ide analog and hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) to prevent HBV reinfection of the graft[2], especially those in high-risk populations: Detectable HBV DNA at the time of liver transplantation[2]; positive for hepatitis B e antigen[2]; coinfection with hepatitis D[3,6,7] or human immunodeficiency virus[6,7]; drug-resistant HBV infection[6]; poor comp

Although HBIGs have been the mainstay of HBV prophylaxis after liver transplantation for many years[8,9], it has been suggested recently that monotherapy with third-generation nucleos(t)ide analogs may be sufficient as a prophylactic option[10,11]. This approach is recommended in the setting of clinical trials, due to the current limited evidence supporting nucleos(t)ide analog monotherapy prophylaxis and the long-term effects of viral persistence in the form of covalently closed circular DNA or viral integration into the host genome[10,11].

HBIG is available in different formulations, with delivery via intramuscular (IM) injection, intravenous (IV) infusion, or subcutaneous (SC) injection, with all three formulations established as efficacious and well tolerated for HBV prophylaxis[12,13]. The formulations differ in terms of dosing and administration schedules[14-16], which may be associated with different cost implications. A prospective study at a single hepatology center of excellence in France demonstrated that a switch from IV HBIG to SC HBIG prophylaxis in 10 liver transplant recipients was associated with a cost saving of €240000 (equivalent to a 48% reduction) over a 3-year period[17]. Cost savings were made due to the possibility to follow an individualized dosage regimen and the lower cost associated with self-administration of the SC formulation[17]. There have also been reports of variations in patient satisfaction and quality of life (QoL) with the different HBIG formulations[18-20]. It has been reported that long-term adherence to post-liver transplant treatment can be problematic, leading to the proposal that patient satisfaction with treatment may improve adherence[21,22]. The SC formulation of HBIG offers the potential for patients to self-administer treatment and avoid the need for assistance from carers or hospital visits to receive therapy, as required for IM or IV administration. Additionally, the SC formulation has been shown to provide better QoL in certain patients and has less administration-associated pain than IM injection[18].

However, there is scant information on how patient preferences and attitudes towards HBIG therapies correlate with individual patient profiles. Also, experience with this treatment in clinical practice from a patient’s perspective has not been explored in depth. The objectives of this patient research study were to understand patient perceptions of their HBIG treatment, including their satisfaction with, and preferences for, SC, IM, or IV modes of administration in order to gain a better understanding of the factors governing their preferences, including patient demographics.

Prior to the study, web-enabled pilot testing of an online questionnaire, comprising two 60-minutes interviews, was conducted in Italy by Cello Health Insight (now Lumanity Insight). In each pilot test, a patient familiar with HBIG treatment completed the questionnaire individually, and, after completion, a member of the research team at Cello Health Insight interviewed the patient to understand any areas of difficulty or misunderstanding. The questionnaire was subsequently amended to ensure maximal clarity and understanding before its wider circulation to the study par

This was an international, cross-sectional study conducted as a self-completion online questionnaire for patients in France, Italy, and Turkey, and was available in the local language. The questionnaire was created using Confirmit software (Confirmit, Oslo, Norway; version 24) and scripted by Ugam (Merkle, Columbia, Maryland, United States). As the study was market research, the protocol was not presented for approval by ethics committees but was conducted in accordance with international market research guidelines from the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association, European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research, and the Market Research Society, and adhered to the provisions of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation regarding data protection and security. In addition, Cello Health Insight abides by the British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association guidelines. The study was conducted from 13 October 2020 to 12 January 2021.

As the eligible study population was anticipated to be small, a purposive sampling methodology was adopted. Physicians treating adult liver transplant recipients who received HBIG therapy post-transplantation in routine clinical practice in France, Italy, and Turkey were identified using a qualitative selection process, supplemented with input from thought leaders and patient association contacts. Suitable physicians were approached as a source of potentially eligible study participants.

Adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) potentially eligible for inclusion in the study were identified through suitable physicians and were subsequently selected to undergo screening. Patient eligibility and provision of verbal informed consent to take part in the market research and for their responses to be analyzed to produce a results report shared with the study sponsor (Biotest AG), were confirmed in a screening interview, conducted by an intermediary market research company in each country. Screening was done via telephone prior to completion of the online questionnaire. During the screening interview, participants were given information about the study, including that their participation was voluntary, they could withdraw their consent at any time during the questionnaire, along with the removal of the data they provided, and that they would receive incentives to compensate them for their time to participate in the study. They were also informed that their personal data (e.g., name, address) would be treated confidentially and were only accessible to the sample providers and their panel partners and stored by the intermediary market research company. Personal data were not disclosed to a third party, including members of the organization conducting the research fieldwork or the analysis (Cello Health Insight), and only an anonymized respondent identification number would be shared with Cello Health Insight. Eligible patients had received a liver transplant with a leading cause of HBV or hepatocellular carcinoma due to HBV; the liver transplant had occurred > 2 months prior to the study; and they were currently receiving, or had received within the last year, HBIG therapy for prophylaxis of HBV infection. To ensure anonymity, each study participant was assigned a unique numerical study identifier by the intermediary country-specific market research company.

The survey took approximately 25 minutes to complete and consisted of 22 questions relating to patients’ current conditions and attitudes to post-transplant therapy, treatment perception, target product profile (TPP) assessment, conjoint (trade-off) exercise, and demographics/lifestyle questions (Supplementary Figure 1). Questions exploring patients’ current perceptions of, and experiences with, post-liver transplant treatment(s) for HBV prophylaxis covered aspects such as the impact of HBIG treatment administration on daily life, any concerns about treatment, important factors about their HBIG treatment (e.g., ease and frequency of administration, side effects of administration, and compliance with dosing), satisfaction with current treatment, and any challenges surrounding treatment. Potential responses to questions were based on a scale of 1-5, multiple-choice phrases, or open-ended responses to help better assess patient experiences in a qualitative manner.

The TPP evaluation was a hypothetical assessment outlining the characteristics (profiles) of three target HBIG products - SC HBIG, IM HBIG, and IV HBIG - to explore the desired characteristics sought after by respondents. For each product, respondents were presented with descriptions of the route of administration (e.g., prefilled syringe injected under skin into belly fat), who would administer treatment (e.g., the patient) and where this would occur (e.g., hospital), the dose, frequency, and duration of administration, and how the product would be stored (e.g., home refrigerator). The conjoint (trade-off) statistical technique was also used to explore respondents’ preferences to help quantify the relative importance given to the different attributes of a product, thereby simulating real-life product decisions. In our study, the conjoint exercise consisted of the presentation of hypothetical HBIG products alongside their attributes (e.g., route of administration) (Supplementary Figure 2). By selecting their preferred product, respondents traded off the importance of attributes associated with one product vs another, enabling comparative measurement of the value of each attribute. Each product attribute was scored between 0% and 100%, thus providing a measure of relative impact on respondents’ product choices.

Survey completion was anonymized. Data were collected by Ugam (Merkle, Columbia, Maryland, United States). Pre-specified clinical and demographic data were recorded for each respondent, including age, sex, occupation, marital status, and current living situation. Country of residence and duration of current HBIG treatment information were also collected.

Upon collection, data inconsistencies and errors were identified and resolved, where possible, then responses to open-ended questions were coded into categories. A member of the research team at Cello Health Insight randomly selected ≥ 10% of responses to ensure the coding had been applied appropriately. Once processed, individual data points were reviewed for each survey question, then core areas of distinction or differentiation were identified. Responses to open-ended questions (verbatim) were translated to English and coded according to categories, and subsequently checked by a member of the research team at Cello Health Insight.

Target recruitment was ≥ 90 respondents based on prior experience recruiting patients for similar studies, since the overall population of eligible patients was known to be small and a larger sample was unrealistic. The number of respondents who completed the online survey per country was 30 from France, 48 from Italy, and 12 from Turkey. Respondent characteristics were described with means and standard deviations (SD), medians and ranges (continuous variables), or numbers and percentages (categorical variables). For assessment of current treatment, TPP, and conjoint analysis, the number and proportion of respondents giving a specific answer were calculated. Between-group differences in responses were tested using t-tests with 95% confidence intervals, but only where group sample sizes were ≥ 29. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Juan Hernandez, Head of Advanced Analytics, Cello Health Insight.

All 90 patients enrolled in the study were currently receiving HBIG therapy, except one patient who had received therapy within the past year but had since discontinued. Approximately half (n = 46; 51%) of patients were receiving IV HBIG, 32% were receiving SC HBIG, and 17% IM HBIG, and 60% of patients had received their current HBIG treatment for up to 20 months (Table 1). The mean ± SD duration of treatment was 36.2 ± 61.0 months.

| Characteristic | SC HBIG, n = 29 | IM HBIG, n = 15 | IV HBIG, n = 46 | Total, n = 90 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 22 (75.9) | 10 (66.7) | 33 (71.7) | 65 (72.2) |

| Female | 7 (24.1) | 5 (33.3) | 13 (28.3) | 25 (27.8) |

| Age in years, mean ± SD | 54.9 ± 10.7 | 49.4 ± 6.5 | 51.9 ± 11.2 | 52.5 ± 10.5 |

| Country of residence, n (%) | ||||

| France | 18 (62.1) | 0 (0) | 12 (26.1) | 30 (33.3) |

| Italy | 11 (37.9) | 15 (100) | 22 (47.8) | 48 (53.3) |

| Turkey | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (26.1) | 12 (13.3) |

| Duration on current HBIG treatment, n (%) | ||||

| 0 month | 2 (6.9) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (4.4) | 5 (5.6) |

| 1-20 months | 15 (51.7) | 14 (93.3) | 24 (53.3) | 53 (59.6) |

| 21-40 months | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (20.0) | 11 (12.4) |

| 41-60 months | 7 (24.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.4) | 9 (10.1) |

| 61 + months | 3 (10.3) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (17.8) | 11 (12.4) |

| mean ± SD | 29.2 ± 28.8 | 8.9 ± 4.5 | 49.8 ± 80.2 | 36.2 ± 61.0 |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Single | 0 | 0 | 3 (6.5) | 3 (3.3) |

| Married/civil partnership | 17 (58.6) | 14 (93.3) | 34 (73.9) | 65 (72.2) |

| In a relationship | 8 (27.6) | 0 | 4 (9.0) | 12 (13.3) |

| Separated/divorced | 4 (13.8) | 1 (6.7) | 3 (6.5) | 8 (8.9) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) |

| Prefer not to answer | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) |

| Living alone, n (%) | 2 (6.9) | 0 | 3 (6.5) | 5 (5.6) |

| Occupation, n (%) | ||||

| Employed full time | 8 (27.6) | 3 (20.0) | 12 (26.1) | 23 (25.6) |

| Employed part time | 4 (13.8) | 5 (33.3) | 3 (6.5) | 12 (13.3) |

| Not working | 6 (20.7) | 6 (40.0) | 20 (43.5) | 32 (35.6) |

| Retired | 8 (27.6) | 0 | 9 (19.6) | 17 (18.9) |

| Other | 3 (10.3) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (4.3) | 6 (6.7) |

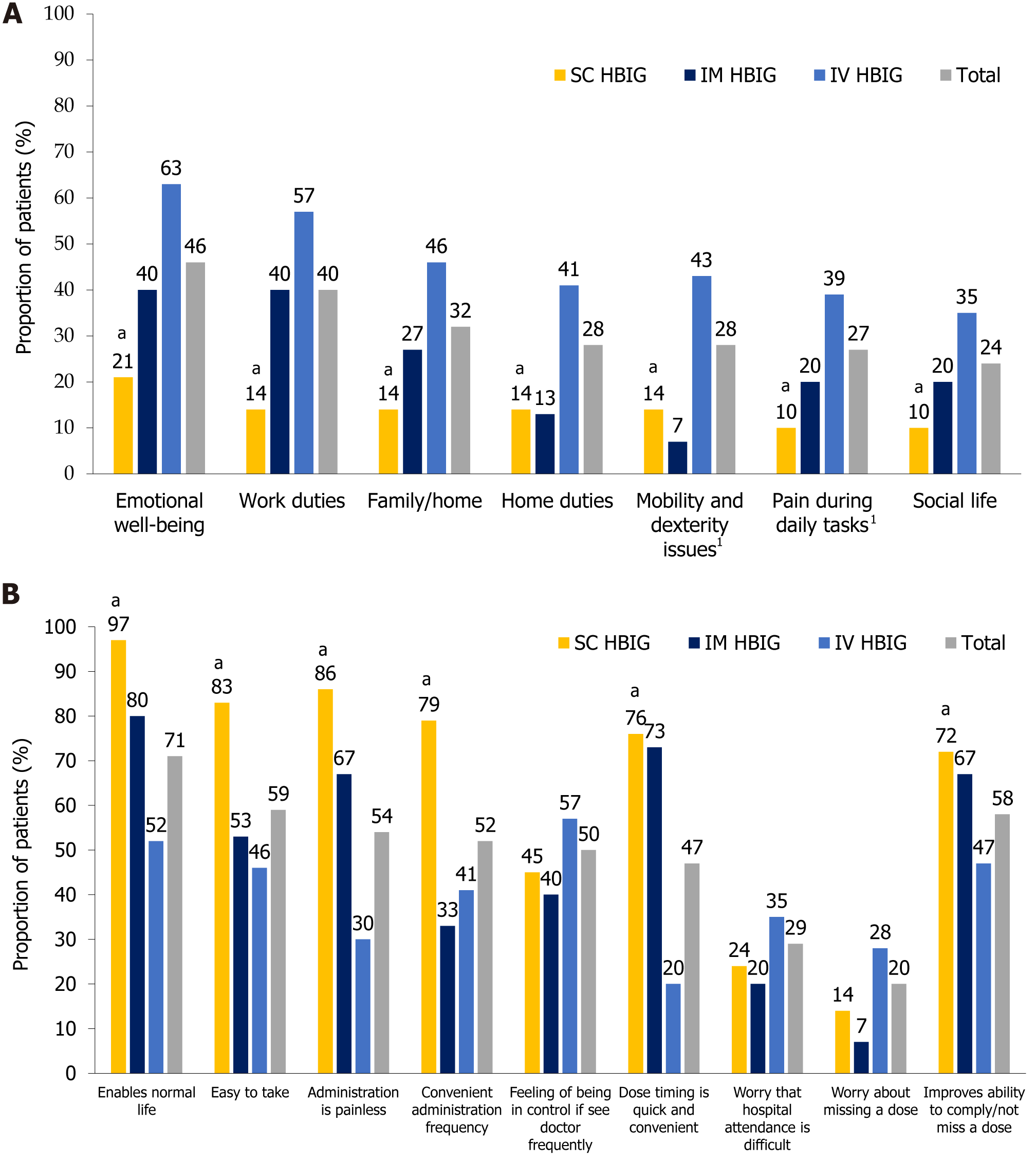

Specific modes of HBIG treatment administration: When respondents evaluated the aspects of life impacted by post-transplant HBIG treatment (questionnaire Q2, Supplementary Figure 1), there were significant differences in favor of SC HBIG vs IV HBIG for all facets explored (P ≤ 0.05 for all comparisons), i.e., SC HBIG had the least negative impact across all aspects (Figure 1A). For instance, SC HBIG had the smallest negative influence on emotional well-being, with 21% of SC HBIG users, 40% of IM HBIG users, and 63% of IV HBIG users giving the highest or second highest rating (‘Completely agree’ or ‘Somewhat agree’) for the statement ‘My emotional well-being has been affected by the need to take HBIG treatments’ (questionnaire Q2, Supplementary Figure 1). Indeed, emotional well-being and work duties were most detrimentally impacted by IV HBIG, and to a lesser extent by IM HBIG (Figure 1A). Compared with IM HBIG, SC HBIG was associated with a marked lesser impact on work duties, family/home life, social life, and pain during daily tasks due to HBIG administration, although statistical analysis was not performed owing to the low number of IM HBIG users.

SC HBIG provided the best patient experience, with 97% of respondents giving the highest or second highest rating for the statement ‘The administration of this medication means I can live a normal life and does not interfere with work/social commitments’ (questionnaire Q3 and Q15, Supplementary Figure 1). The proportion of patients who gave the same rating for IM HBIG was 80% (Figure 1B). Of the three delivery modes, SC HBIG was perceived as the most convenient, easiest to administer, least painful, and to have the highest treatment compliance rating (measured as a rating of agreement/disagreement with the statement ‘Improves my ability to comply/not miss a dose’) (Figure 1B).

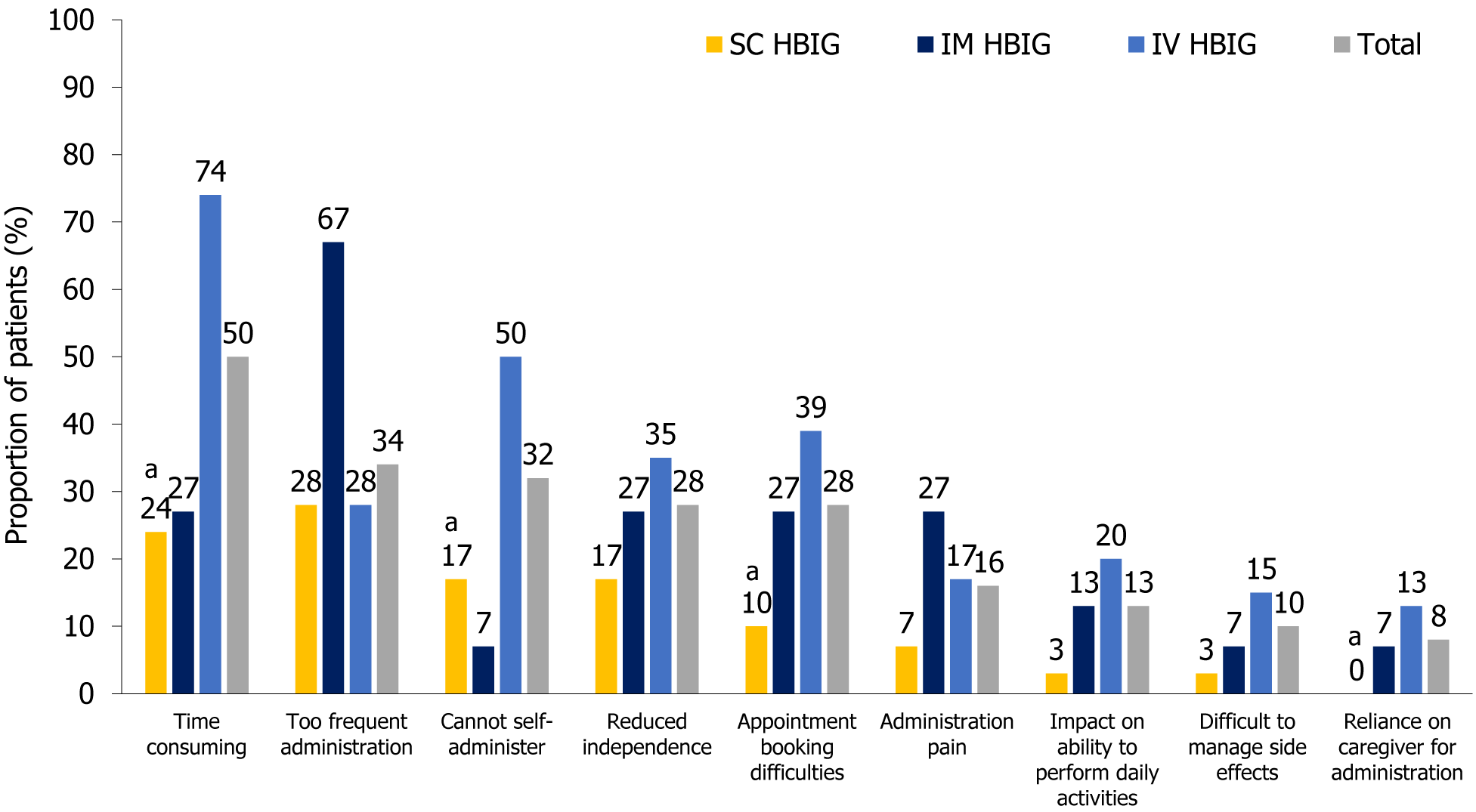

Among the challenges of HBIG therapy (questionnaire Q7, Supplementary Figure 1), the highest burden of administration frequency was reported by IM HBIG users, with a relatively greater number reporting that administration frequency was excessive compared with other modes of administration [67% vs SC (28%) and IV HBIG (28%)] (Figure 2), which may potentially be related to administration pain. More IM HBIG users (27%) perceived administration pain to be a challenge vs SC HBIG (7%) and IV HBIG users (17%) (Figure 2). The time-consuming nature of the procedure was the most frequently named issue for IV HBIG users (74%, Figure 2), presumably because patients were required to travel to hospital for treatment. SC HBIG was perceived as being the least obstructive mode of administration, enabling patients to maintain independence and the ability to perform daily activities, and it was the administration mode associated with the least difficulty in booking HBIG administration appointments and managing side effects (Figure 2).

HBIG treatment in general: Regardless of respondents’ current mode of HBIG administration, we found that patient age influenced the life aspects affected by treatment. A greater proportion of younger than older recipients (aged ≤ 55 vs > 56 years) were adversely affected by the need to take HBIG treatment in relation to family/home life, such as relationship with a partner (37% vs 23%) and social life (32% vs 10%; P ≤ 0.05). In addition, a greater proportion of younger than older recipients felt the need to take HBIG treatment affected work duties (47% vs 27%), home duties, including typical household responsibilities (32% vs 20%), emotional well-being (52% vs 33%), and physical capabilities (33% vs 13%; P ≤ 0.05).

When patients were asked about the ability to live a normal life in relation to the need to take their HBIG treatment (questionnaire Q3, Supplementary Figure 1), the duration of HBIG treatment appeared to influence responses. A significantly greater proportion of patients on HBIG treatment for the longest duration (≥ 21 months) thought that the frequency of current administration was convenient (71% vs 42% for administration < 20 months; P ≤ 0.05) and gave the highest or second highest rating for the statement, ‘The administration of this medication means I can live a normal life and does not interfere with work/social commitments’.

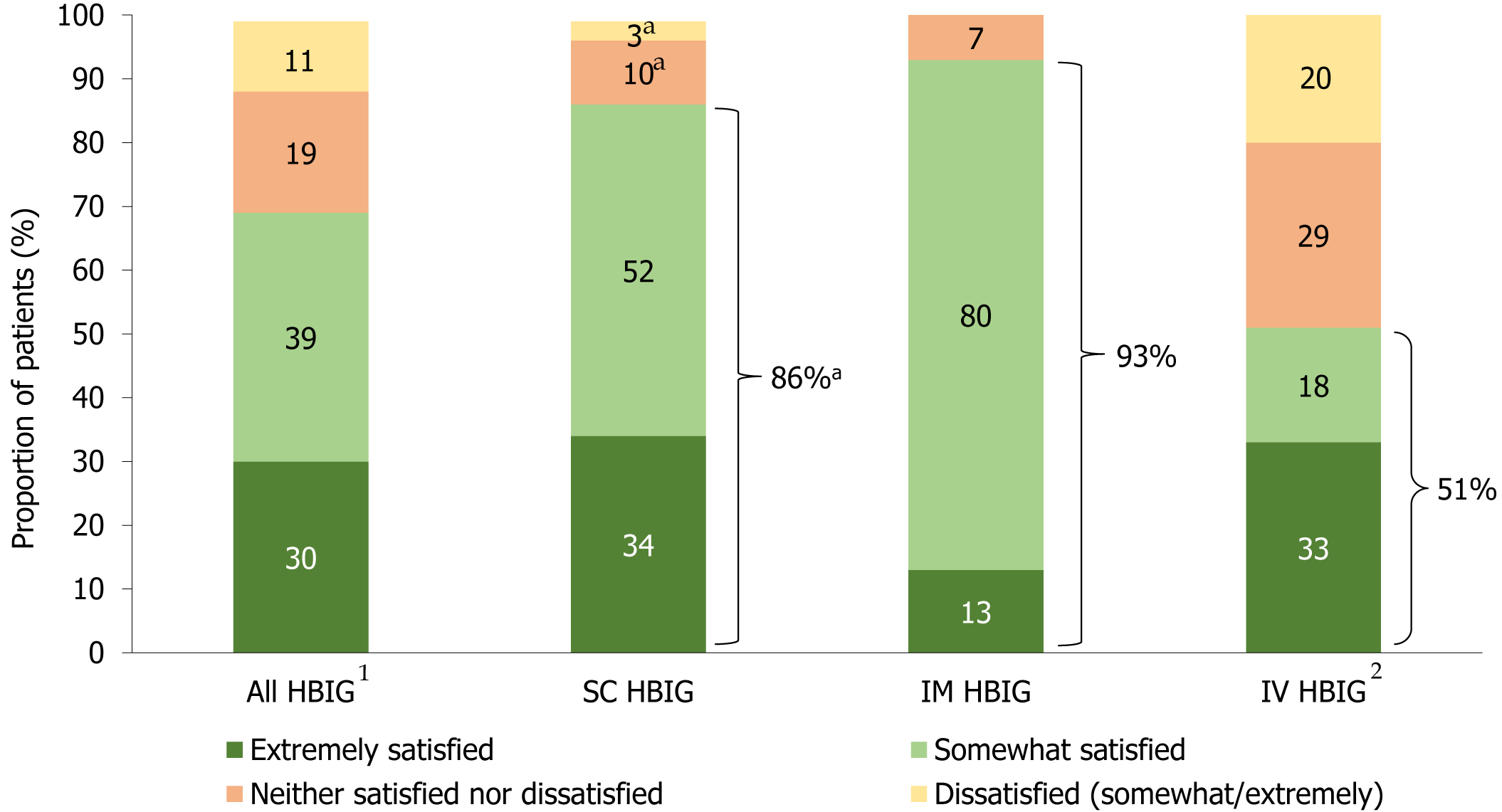

When questioned about overall satisfaction with HBIG therapy (questionnaire Q13, Supplementary Figure 1), 86% of SC HBIG users were satisfied with treatment, with approximately one-third (34%) being extremely satisfied. Almost all (93%) IM HBIG users were satisfied with treatment (13% were extremely satisfied), while approximately half (51%) of IV HBIG users were satisfied with treatment (33% were extremely satisfied) (Figure 3). Overall satisfaction with HBIG therapy was similar when analyzed by respondent age [≤ 55 years (69%) vs > 56 years (70%)] and duration on HBIG therapy [< 20 months (71%) vs ≥ 21 months (68%)].

Administration frequency was a significant burden of HBIG treatment for many respondents, regardless of the administration mode (questionnaire Q7, Supplementary Figure 1), and there were clear differences in perception according to patient characteristics. More respondents who were younger [≤ 55 years (45%) vs > 56 years (13%); P ≤ 0.05], had been on HBIG therapy for the shortest duration [< 20 months (46%) vs ≥ 21 months (13%); P ≤ 0.05], were married [42% vs not married (16%); P ≤ 0.05], and who were employed or not working (34% and 56%, respectively, vs retired 0%) found HBIG administration frequency to be burdensome.

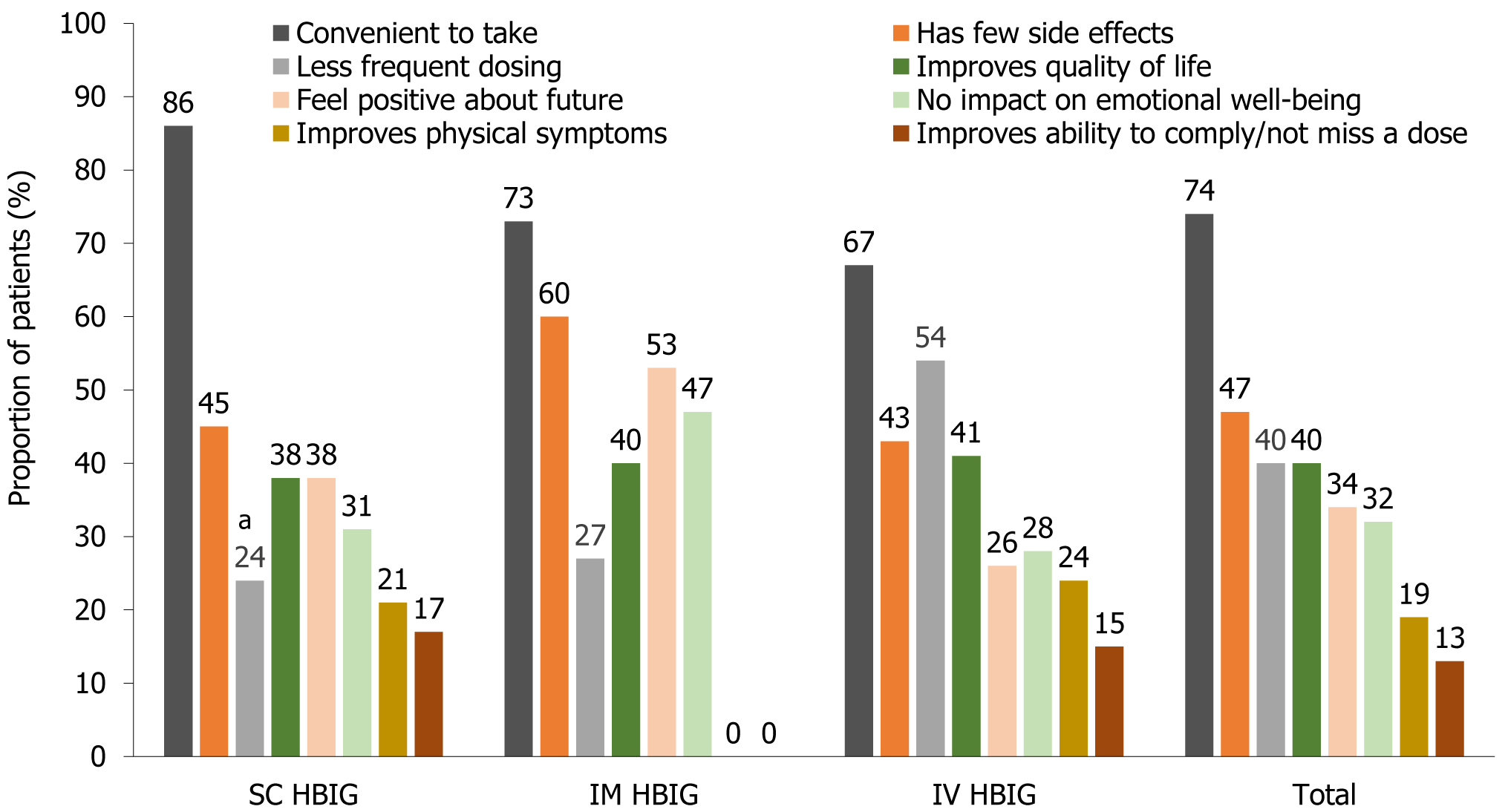

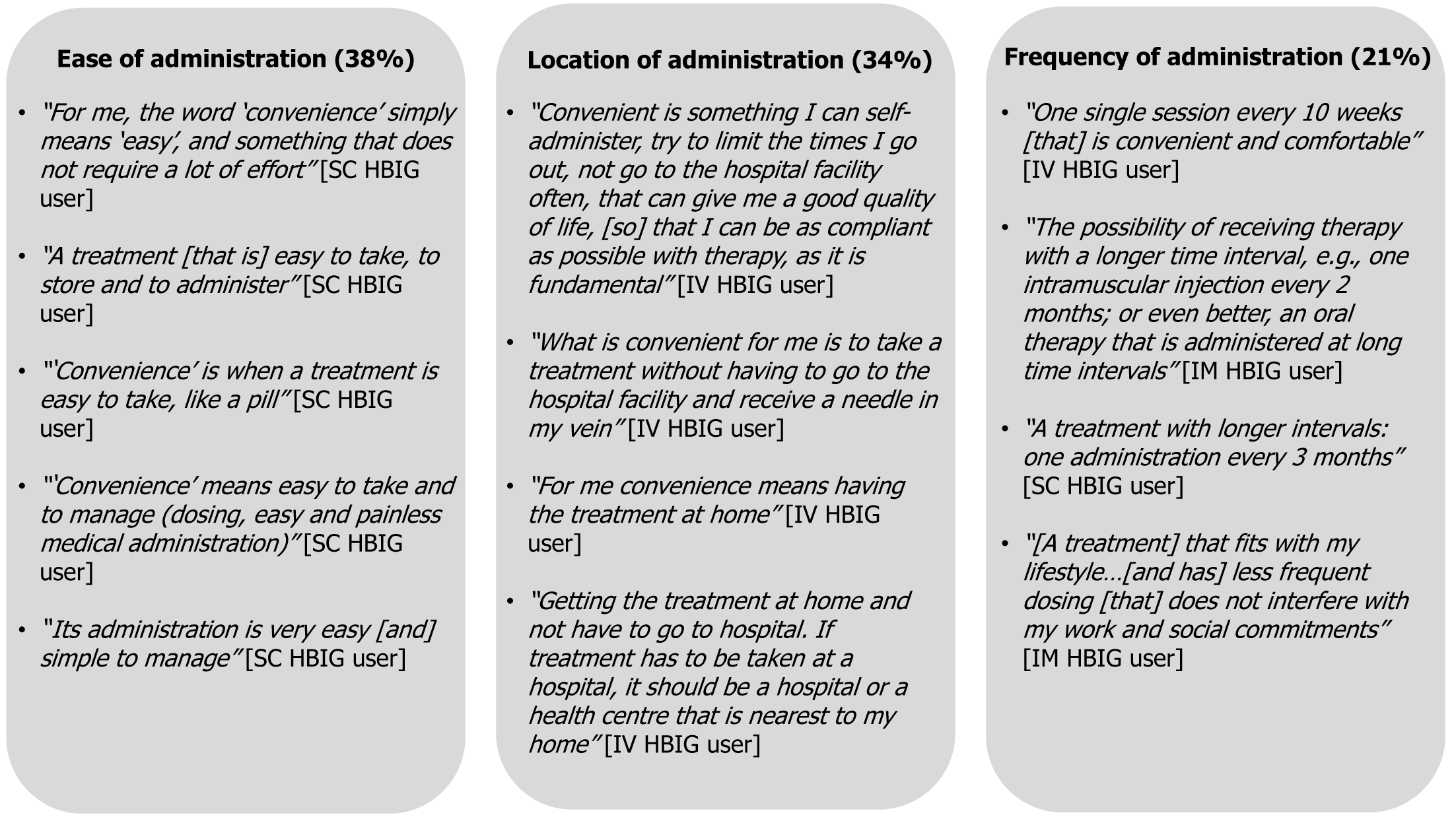

During evaluation of current treatments, some questions asked which features of HBIG therapy were favorable, which could be improved, and how this could be done. This formed part of the assessment of treatment features that influenced preferences. A key factor important for HBIG treatment (questionnaire Q4, Supplementary Figure 1) was convenience and was the single most highly rated driver of treatment selection (74% overall), followed by fewer side effects (47% overall) (Figure 4). Perception of convenience varied according to patients’ current experience (Figure 5). For SC HBIG users, ease of administration was key to convenience, as mentioned by 38% of respondents, whereas for IM HBIG users, low frequency was key (21% of respondents); for IV HBIG users, the location at which their treatment was administered was key (34% of respondents). A greater number of younger than older respondents (< 55 years vs ≥ 56 years) thought that less frequent dosing than their current treatment was important when selecting a treatment (45% vs 30%), for improving perception of QoL (45% vs 30%) and for ability to comply with treatment (15% vs 10%), although differences were not statistically significant.

All patients, regardless of current mode of HBIG treatment administration, were asked whether, after training, they would consider self-administering HBIG treatment (questionnaire Q9, Supplementary Figure 1), with 61% of all patients (79% of SC HBIG users, 67% of IM HBIG users, and 48% of IV HBIG users) responding that it would be easy to self-administer the given treatment. While SC HBIG is intended for self-administration, not all patients receiving this treatment do so. A significantly greater proportion of respondents currently receiving SC HBIG would be willing to self-administer HBIG treatment than the proportion of those currently receiving IV HBIG (P ≤ 0.05). Respondents who were younger [≤ 55 years (67%) vs > 56 years (50%)], had been on HBIG for a shorter duration [< 20 months (64%) vs ≥ 21 months (55%)], and who were not married (72%) vs married (57%) were more likely to consider self-administration of HBIG treatment to be easy. In contrast, significantly more older respondents (> 56 years) thought that self-administration of HBIG treatment would be difficult for them (37% vs 8% for respondents aged ≤ 55 years; P ≤ 0.05). All respondents, regardless of current mode of HBIG treatment, were also asked how confident they would feel to self-administer HBIG treatment in specific situations. The greatest confidence was declared by patients in situations where ‘no-one reminded them to take treatment’ (79% for SC HBIG users, 73% for IM HBIG users, and 85% for IV users); ‘they took treatments more than once a day for different conditions’ (79% for SC HBIG users, 73% for IM HBIG users, and 72% for IV users); ‘they took several different treatments each day for several conditions’ (76% for SC HBIG users, 80% for IM HBIG users, and 65% for IV users); and ‘they had a busy day planned’ (76% for SC HBIG users, 67% for IM HBIG users, and 63% for IV users).

Results from the TPP hypothetical assessment provided an indication of HBIG treatment factors that triggered favorable responses by patients. In the TPP assessment, 68 (76%) patients responded that they would likely use a hypothetical SC HBIG product, and, of current SC HBIG users, 21 (72%) patients had a positive impression of a hypothetical SC HBIG product. When responses in the TPP assessment were evaluated by patient characteristics, younger respondents (≤ 55 years vs > 56 years) and those on HBIG treatment for a shorter duration (mean 28.8 months vs 57.6 months) were associated with a positive impression of SC HBIG treatment. The mean age of those likely to use SC HBIG was 51 years, vs 58 years for those unlikely to use SC HBIG. Of the 46 current IV HBIG users, 34 (74%) stated willingness to switch to SC HBIG, with a similar demographic pattern to the overall group (i.e., younger age and shorter duration on HBIG treatment). The mean age of those likely to switch from IV to SC HBIG treatment was 49 years, and 61 years for those unlikely to switch. However, only 12 patients (26%) were unlikely to switch from IV HBIG to SC HBIG, therefore results should be interpreted with caution. Likewise, the overall numbers of SC HBIG users (n = 29) and IM HBIG users (n = 15) were too low for statistical analysis. Regardless of current mode of HBIG treatment administration, among 22 respondents who were unlikely to use a hypothetical SC HBIG product, a barrier to using SC HBIG treatment was the perceived difficulty of self-administering treatment [mentioned by 10 (45%) patients]. However, while there was a greater degree of confidence with treatment compliance without having to be reminded to take a dose among respondents likely to use a hypothetical SC HBIG product [59 (87%)], there was still a substantial majority of respondents unlikely to use this product [14 (64%)] who also declared they would be confident with being compliant with treatment.

In the conjoint (trade-off) exercise (questionnaire Q22, Supplementary Figure 1), respondents were presented with descriptions of hypothetical HBIG products with differing modes of administration, to help refine the importance of specific features that drove individual preferences, i.e., respondents traded off attributes of one product against those of another. Results were reported as a preference share of 100% (rounded to the nearest percentage point). Overall, SC HBIG was the preferred choice of treatment, with 43% preference share, while IM HBIG was assigned 41% preference share, and 17% to IV HBIG. The route, frequency, and duration of administration of a hypothetical novel HBIG treatment were the three key drivers of treatment preferences, with a derived relative importance weighting of 30%, 21%, and 20%, respectively. Frequency of administration ranked as a highly important factor for IM HBIG and IV HBIG users, with a relative importance weighting of 21% and 24% among respondents currently on IM HBIG and IV HBIG treatments, respectively, compared with a lower weighting of 17% among SC HBIG users.

This study provides valuable insights into the perspectives of patients in clinical practice regarding current HBIG treatment and preferences for attributes associated with different administration modes of HBIG treatment. Our study showed that SC HBIG provided the best overall experience, with a high level of satisfaction among current users. When the three modes of HBIG therapy were analyzed by current treatment experiences, SC HBIG had the least impact across all life aspects evaluated, and was perceived to be the most convenient, easiest to administer, and least painful, and had the highest compliance rating of the three delivery modes of HBIG treatment.

During exploration of preferences for a hypothetical, novel HBIG treatment, key drivers for all patients, regardless of current mode of HBIG treatment administration, were route, frequency, and duration of administration. However, it appeared that for patients with modes of administration that required assistance (i.e., IM and IV HBIG), administration frequency was a prominent factor, which possibly reflected the desire by these patients for less frequent and less painful treatment. In a systematic review of patient preferences on route of treatment administration for chronic immune disorders, preference for a route that offered lower treatment frequency was a key driver for most patients[23]. A greater administration frequency has been postulated as a factor in reduced adherence to chronic treatment for multiple sclerosis in a comparison of two administration modes of interferon-beta-1α, and that patient preferences should be considered to ensure optimal treatment adherence[24]. In our study, administration frequency and pain were also highlighted as key negative factors of current treatment among IM HBIG users more than among IV HBIG users or SC HBIG users. Previously, Franciosi et al[21] reported that injection site pain was a relevant side effect of treatment with HBIG therapies impacting patient QoL. Administration frequency was not an issue for SC HBIG users, presumably because patients could self-administer treatment without reliance on others, and it was associated with the lowest incidence of pain. The latter observation concurs with the findings of a small study in 12 patients undergoing conversion from IM to SC HBIG, in which patients reported substantially lower pain and discomfort, and improved satisfaction with SC than with IM administration[25,26]. Patient adherence and satisfaction with SC HBIG therapy was high in two larger studies, with patients successfully self-administering therapy with reduced interference with daily life and maintenance of hepatitis B surface antibody serum levels (a measure of adherence failure in one study)[18,27]. A high level of patient satisfaction with treatment may naturally lead to high levels of treatment compliance, and thus prevent a possible HBV recurrence due to low adherence and its associated costs, as dem

While patients with IV delivery of HBIG commented about some of the negative connotations of the mode of administration, such as invasive and painful administration, and the need for hospital-based administration, some of these patients preferred IV administration and the assistance required, and they were unlikely to want to change to another mode of administration. Our observations revealed an age-related preference for IV administration. Older patients may be more likely to receive IV HBIG because their physicians consider them unable to manage SC or IM HBIG administration themselves, which may explain their reluctance to switch treatments. We observed that a significantly greater proportion of older respondents (aged > 56 years) thought that self-administering HBIG treatment would be difficult for them and IV HBIG users who were likely to switch to SC HBIG were substantially younger than those who were likely to remain on IV HBIG (49 years vs 61 years, respectively). Previous studies indicate that patients who preferred IV rather than SC administration of treatment for chronic immune disorders cited a dislike of injections, the opportunity for social contact in hospital, and a preference for the presence of medical staff during administration as reasons for their decision[23].

Patient demographics appeared to influence treatment preferences in the TPP assessment of hypothetical HBIG products, with older patients aged > 56 years preferring modes of administration requiring social contact, while younger patients aged ≤ 55 years sought more independent means of administration. In our study, the mean age of patients likely to use SC HBIG was younger than those unlikely to use this mode of administration (51 vs 58 years, respectively). During development of a QoL questionnaire for evaluation of HBIG treatments in liver transplant patients, Franciosi et al[21] reported that older patients were less negatively affected by side effects than younger patients, which could also be a factor in our study explaining patient preferences in relation to age.

Evaluating the efficacy and safety of the different HBIG formulations was beyond the scope of the present study. A prospective, open-label, multicenter international study in 49 liver transplant recipients negative for HBV DNA reinforced that an early switch (by 3 weeks) post-transplant from IV to SC HBIG led to maintenance of anti-hepatitis B antibody trough levels at 100 IU/L throughout the 6-months duration of the study, with no reports of hepatitis B surface antigen positivity[29]. In addition, a recent prospective, single-arm, multicenter, international study showed a low incidence of HBV recurrence [7/195 patients (3.6%); annual rate: 2.01%] and low incidence of HBV-hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence [4/83 patients (4.8%); annual rate 2.88%][31]. Longer-term data also provide support for the efficacy of SC HBIG. After a mean 6.8 years of follow-up of 371 liver transplant recipients across 20 European centers who received either IV or SC HBIG immediately after transplantation [with 236 patients (63.6%) switching from the IV to the SC formulation], the risk of recurrent HBV infection increased by a factor of 5.2 in those who discontinued HBIG therapy compared to those who continued SC HBIG[13]. Moreover, there were no reports of HBV infection in patients who received adequate SC HBIG treatment (anti-HB antibody levels at > 100 IU/L)[12]. Regarding safety data, among 135 lung transplant recipients who switched from monthly IV to weekly SC HBIG and administered a total of 9296 injections, there were no severe drug-related side effects, 15 injection-site small hematomas and four cases of mild itch[32]. There were no changes in safety laboratory parameters or premature treatment discontinuations because of adverse events or lack of efficacy during the 6-months study period[32]. During long-term (mean 6.8 years) follow-up of 371 liver transplant recipients, there were no reports of HBIG-associated adverse events, while acute graft rejection occurred in 37 patients (10.0%) and chronic rejection occurred in seven patients (1.9%)[12]. Also, previous studies have shown that switching between formulations does not have a detrimental impact on anti-HB antibody level, HBV reinfection, or safety aspects[28,29,32]. Reports from two prospective, open-label studies in, respectively, 23 and 135 lung transplant recipients negative for both HBV DNA and hepatitis B surface antigen showed that a switch from prophylactic monthly IV HBIG to weekly SC HBIG maintained serum anti-HB antibody levels at > 100 IU/L (the minimum protective anti-HB antibody level) throughout the 24- or 48-weeks duration of the studies, with no reports of HBV reinfection[28,32].

While the intention in our study was to recruit more than 90 patients, enrollment was difficult; therefore, a limitation of the study was the low number of patients. However, it is notable that in the TPP assessment, almost three-quarters of current SC HBIG users had a positive impression of a hypothetical SC HBIG product. In addition, the low number of patients in the IM administration group meant that statistical comparisons with the other modes of administration were not possible. While TPP assessments and conjoint (trade-off) analyses are commonly used to survey patient preferences in the healthcare market research setting, the hypothetical nature of these evaluations has some limitations. These questions were intended to simulate possible clinical decisions, but they do not share the same clinical and emotive consequences of actual decisions, which could lead to differences between perceived and actual preferences. To minimize potential disparities, the hypothetical scenarios were constructed with detailed information based on real-life trade-offs regarding different modes of HBIG therapy administration.

The ease, frequency, duration, and side effects of HBIG treatment administration were key drivers of treatment preferences in this survey of liver transplant recipients receiving prophylactic HBIG therapy. The SC mode of HBIG treatment administration appeared to confer advantages over IM and IV administration among current users, with SC HBIG receiving the highest rating in terms of convenience, ease of administration, and least painful mode of administration. Additionally, analysis of the drivers of treatment preferences pointed to a favorable response to a hypothetical SC HBIG product. Our survey indicated that older respondents (aged > 56 years) may prefer IV HBIG therapy, and this mode of treatment may benefit patients requiring assistance to receive treatment or in circumstances where SC HBIG is not available. Adherence with long-term treatment, necessary in liver transplant patients with previous HBV-associated disease, is key for the prevention of HBV reinfection. An appreciation of individual patient demographics, lifestyle, personal preferences, and satisfaction with HBIG treatment modalities is essential to ensure treatment compliance and the least interference with daily life.

This study was initiated and supported by Biotest AG. Medical writing support was provided by Rhian Harper Owen, PhD, for Lumanity (previously Cello Health Insight), funded by Biotest AG. The data and conclusions are endorsed by Juan Hernandez, the Head of Advanced Analytics, Lumanity (previously Cello Health Insight).

| 1. | Dutkowski P, Linecker M, DeOliveira ML, Müllhaupt B, Clavien PA. Challenges to liver transplantation and strategies to improve outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:307-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3745] [Cited by in RCA: 3801] [Article Influence: 475.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | British Transplantation Society. Guidelines for hepatitis B & solid organ transplantation. 2018. [cited 20 December 2023]. Available from: https://bts.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/BTS-Hep-B-Guidelines-26-Jan-2018-web-consultation.pdf. |

| 4. | Chauhan R, Lingala S, Gadiparthi C, Lahiri N, Mohanty SR, Wu J, Michalak TI, Satapathy SK. Reactivation of hepatitis B after liver transplantation: Current knowledge, molecular mechanisms and implications in management. World J Hepatol. 2018;10:352-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lenci I, Milana M, Grassi G, Manzia TM, Gazia C, Tisone G, Angelico R, Baiocchi L. Hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation: An old tale or a clear and present danger? World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:2166-2176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, Abbas Z, Chan HL, Chen CJ, Chen DS, Chen HL, Chen PJ, Chien RN, Dokmeci AK, Gane E, Hou JL, Jafri W, Jia J, Kim JH, Lai CL, Lee HC, Lim SG, Liu CJ, Locarnini S, Al Mahtab M, Mohamed R, Omata M, Park J, Piratvisuth T, Sharma BC, Sollano J, Wang FS, Wei L, Yuen MF, Zheng SS, Kao JH. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:1-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1985] [Cited by in RCA: 1959] [Article Influence: 217.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Brown RS Jr, Bzowej NH, Wong JB. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2290] [Cited by in RCA: 2844] [Article Influence: 406.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kasraianfard A, Watt KD, Lindberg L, Alexopoulos S, Rezaei N. HBIG Remains Significant in the Era of New Potent Nucleoside Analogues for Prophylaxis Against Hepatitis B Recurrence After Liver Transplantation. Int Rev Immunol. 2016;35:312-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Park GC, Hwang S, Kim MS, Jung DH, Song GW, Lee KW, Kim JM, Lee JG, Ryu JH, Choi DL, Wang HJ, Kim BW, Kim DS, Nah YW, You YK, Kang KJ, Yu HC, Park YH, Lee KJ, Kim YK. Hepatitis B Prophylaxis after Liver Transplantation in Korea: Analysis of the KOTRY Database. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Battistella S, Zanetto A, Gambato M, Germani G, Senzolo M, Burra P, Russo FP. The Role of Antiviral Prophylaxis in Preventing HBV and HDV Recurrence in the Setting of Liver Transplantation. Viruses. 2023;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Duvoux C, Belli LS, Fung J, Angelico M, Buti M, Coilly A, Cortesi P, Durand F, Féray C, Fondevila C, Lebray P, Martini S, Nevens F, Polak WG, Rizzetto M, Volpes R, Zoulim F, Samuel D, Berenguer M. 2020 position statement and recommendations of the European Liver and Intestine Transplantation Association (ELITA): management of hepatitis B virus-related infection before and after liver transplantation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54:583-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Beckebaum S, Herzer K, Bauhofer A, Gelson W, De Simone P, de Man R, Engelmann C, Müllhaupt B, Vionnet J, Salizzoni M, Volpes R, Ercolani G, De Carlis L, Angeli P, Burra P, Dufour JF, Rossi M, Cillo U, Neumann U, Fischer L, Niemann G, Toti L, Tisone G. Recurrence of Hepatitis B Infection in Liver Transplant Patients Receiving Long-Term Hepatitis B Immunoglobulin Prophylaxis. Ann Transplant. 2018;23:789-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Biotest Pharma. Summary of Product Characteristics. 2019. [cited 20 December 2023]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/zutectra-epar-product-information_en.pdf. |

| 14. | Cholongitas E, Goulis J, Akriviadis E, Papatheodoridis GV. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin and/or nucleos(t)ide analogues for prophylaxis against hepatitis b virus recurrence after liver transplantation: a systematic review. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:1176-1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lok AS. Prevention of recurrent hepatitis B post-liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:S67-S73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Angus PW, McCaughan GW, Gane EJ, Crawford DH, Harley H. Combination low-dose hepatitis B immune globulin and lamivudine therapy provides effective prophylaxis against posttransplantation hepatitis B. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:429-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lebray P, Liou-Schimanoff A, Bourguignon S, Barlozek M. Subcutaneous immunoprophylaxis as a cost-effective treatment alternative for hepatitis B virus-related transplant patients in France. Value Health. 2017;20. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Volpes R, Burra P, Germani G, Manini MA, Caccamo L, Strignano P, Rizza G, Tamè M, Pinna AD, Calise F, Migliaccio C, Carrai P, De Simone P, Valentini MF, Lupo LG, Cordone G, Picciotto FP, Nicolucci A. Switch from intravenous or intramuscular to subcutaneous hepatitis B immunoglobulin: effect on quality of life after liver transplantation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Roche B, Roque-Afonso AM, Nevens F, Samuel D. Rational Basis for Optimizing Short and Long-term Hepatitis B Virus Prophylaxis Post Liver Transplantation: Role of Hepatitis B Immune Globulin. Transplantation. 2015;99:1321-1334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shouval D, Samuel D. Hepatitis B immune globulin to prevent hepatitis B virus graft reinfection following liver transplantation: a concise review. Hepatology. 2000;32:1189-1195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Franciosi M, Caccamo L, De Simone P, Pinna AD, Di Costanzo GG, Volpes R, Scuderi V, Strignano P, Boccagni P, Burra P, Nicolucci A; TWINS I Study Group. Development and validation of a questionnaire evaluating the impact of hepatitis B immune globulin prophylaxis on the quality of life of liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:332-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Albekairy AM, Alkatheri AM, Jarab A, Khalidi N, Althiab K, Alshaya A, Saleh KB, Ismail WW, Qandil AM. Adherence and treatment satisfaction in liver transplant recipients. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:127-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Overton PM, Shalet N, Somers F, Allen JA. Patient Preferences for Subcutaneous versus Intravenous Administration of Treatment for Chronic Immune System Disorders: A Systematic Review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:811-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jin JF, Zhu LL, Chen M, Xu HM, Wang HF, Feng XQ, Zhu XP, Zhou Q. The optimal choice of medication administration route regarding intravenous, intramuscular, and subcutaneous injection. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:923-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yoshida EM, Partovi N, Greanya ED. Subcutaneous hepatitis B immune globulin after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Singham J, Greanya ED, Lau K, Erb SR, Partovi N, Yoshida EM. Efficacy of maintenance subcutaneous hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) post-transplant for prophylaxis against hepatitis B recurrence. Ann Hepatol. 2010;9:166-171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Klein CG, Cicinnati V, Schmidt H, Ganten T, Scherer MN, Braun F, Zeuzem S, Wartenberg-Demand A, Niemann G, Schmeidl R, Beckebaum S. Compliance and tolerability of subcutaneous hepatitis B immunoglobulin self-administration in liver transplant patients: a prospective, observational, multicenter study. Ann Transplant. 2013;18:677-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yahyazadeh A, Beckebaum S, Cicinnati V, Klein C, Paul A, Pascher A, Neuhaus R. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous human HBV-immunoglobulin (Zutectra) in liver transplantation: an open, prospective, single-arm phase III study. Transpl Int. 2011;24:441-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | De Simone P, Romagnoli R, Tandoi F, Carrai P, Ercolani G, Peri E, Zamboni F, Mameli L, Di Benedetto F, Cillo U, De Carlis L, Lauterio A, Lupo L, Tisone G, Prieto M, Loinaz C, Mas A, Suddle A, Mutimer D, Roche B, Wartenberg-Demand A, Niemann G, Böhm H, Samuel D. Early Introduction of Subcutaneous Hepatitis B Immunoglobulin Following Liver Transplantation for Hepatitis B Virus Infection: A Prospective, Multicenter Study. Transplantation. 2016;100:1507-1512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Volpes R, Burra P, Germani G, Strignano P, Rizza G, Migliaccio C, Calise F, Tamé M, Pinna AD, Manini M, Caccamo L, Carrai P, De Simone P, Mari FV, Lupo LG, Cordone G, Picciotto F, Nicolucci A. Switching from intramuscular or intravenous to subcutaneous hepatitis B immune globulin improves the quality of life of liver transplant recipients. Transpl Int. 2015;28:235. |

| 31. | Roche B, Bauhofer A, Gomez Bravo MÃ, Pageaux GP, Zoulim F, Otero A, Prieto M, Baliellas C, Samuel D. Long-Term Effectiveness, Safety, and Patient-Reported Outcomes of Self-Administered Subcutaneous Hepatitis B Immunoglobulin in Liver Post-Transplant Hepatitis B Prophylaxis: A Prospective Non-Interventional Study. Ann Transplant. 2022;27:e936162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Di Costanzo GG, Lanza AG, Picciotto FP, Imparato M, Migliaccio C, De Luca M, Scuderi V, Tortora R, Cordone G, Utech W, Calise F. Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous hepatitis B immunoglobulin after liver transplantation: an open single-arm prospective study. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:348-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |