Published online Oct 14, 2018. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v8.i4.108

Peer-review started: April 30, 2018

First decision: July 10, 2018

Revised: July 24, 2018

Accepted: August 21, 2018

Article in press: August 21, 2018

Published online: October 14, 2018

Processing time: 165 Days and 22.2 Hours

To explore the association between metacognitive beliefs, rumination and shyness in a non-clinical sample of adults.

One hundred and three healthy subjects from the general population were enrolled in the study. Shyness was evaluated using the Revised Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale, rumination was assessed using the Ruminative Response Scale, metacognition was evaluated using the Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire 30, and anxiety levels were measured using the State Trait Anxiety Inventory form Y. Correlation analyses, mediation models and 95% bias-corrected and accelerated (BCaCI) bootstrapped analyses were performed. Mediation analyses were adjusted for sex and anxiety.

Shyness, rumination and metacognition were significantly correlated (P < 0.05). The relationship between metacognition and shyness was fully mediated by rumination (Indirect effect: 0.20; 95% BCaCI: 0.08-0.33).

These findings suggest an association between metacognition and shyness. Rumination mediated the relationship between metacognition and shyness, suggesting that rumination could be a cognitive strategy for shy people. Future research should explore the relationship between these constructs in more depth.

Core tip: No previous studies have explored the relationship between metacognitive belief, rumination and shyness in a sample of adults. This research, based on the self-regulatory executive function model, explores the association between metacognitive beliefs, rumination and shyness. Results show a correlation between shyness, rumination and metacognition. Moreover, the relationship between metacognition and shyness was fully mediated by rumination. These findings have important implications for strengthening the social skills of shy individuals.

- Citation: Palmieri S, Mansueto G, Scaini S, Fiore F, Sassaroli S, Ruggiero GM, Borlimi R, Carducci BJ. Role of rumination in the relationship between metacognition and shyness. World J Psychiatr 2018; 8(4): 108-113

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v8/i4/108.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v8.i4.108

The self-regulatory executive function model (S-REF)[1] has been proposed by Well and Matthews to describe dysfunctional cognition in psychological distress. The S-REF model posits that psychological dysfunction may be maintained by a combination of attentional focusing on threat, rumination, worry, and dysfunctional behaviours, which constitute the Cognitive Attentional Syndrome (CAS)[2]. CAS is activated and maintained by metacognitive beliefs, which are defined as the information that an individual has about his/her own cognition and coping strategies, which ultimately impact CAS[2]. Metacognitive beliefs take two forms: Positive and negative. Positive metacognitive beliefs motivate the use of CAS. Negative metacognitive beliefs concern the significance, uncontrollability and danger of thoughts[3]. In the S-REF model, CAS is considered problematic because it causes negative thoughts and emotions to persist, leading to failed modifications of dysfunctional metacognitive beliefs and stably resolved self-discrepancies[4].

The importance of metacognitive beliefs can be explained with reference to generalized anxiety disorder[5]. In the presence of a trigger (e.g., intrusive thoughts and/or external factors), positive metacognitive beliefs about the usefulness of worrying as a coping strategy toward a threat are activated and persist until the person achieves a desired internal feeling state. Positive beliefs are not sufficient to lead to generalized anxiety disorder, and the development of negative beliefs about worrying contributes to an intensification of anxiety symptoms[5].

Rumination is one component of CAS and it has been defined, in the context of social anxiety, as repetitive thoughts about subjective experiences during a recent social interaction, including self-appraisal and the external evaluations of partners and other details of the event[6].

Several studies have found a significant correlation between metacognitive beliefs and rumination in both clinical and non-clinical samples[7-9]. Metacognitive beliefs and rumination have been found to be positively-correlated with a wide range of psychological disorders[4,10-12], including social anxiety[13,14]. Patients with social anxiety focus their attention onto an “observer” image of themselves in social circumstances by engaging in ruminative activities after social encounters[5]. The post-event involves ruminations about what happened in the social situation, is focused on negative emotions and image of oneself, and leads to reinforced beliefs about one’s poor social performance and negative self-perceptions[5].

In comparison with a non-clinical control group, patients with social anxiety reported higher levels of negative metacognitive beliefs regarding the uncontrollability and dangerousness of thoughts[15]. For those in clinical samples with beliefs about the need to control thoughts[16], positive and negative metacognitive beliefs were positively-associated with social anxiety symptoms[13]. Similarly, in non-clinical samples, a positive correlation was reported between positive metacognitive beliefs about post-event rumination, negative metacognitive beliefs and social anxiety[13].

Although it has been hypothesised that shyness could be qualitatively different from social anxiety[17], some evidence places shyness and social anxiety on a continuum or spectrum in which social anxiety is conceptualised as ‘‘extreme shyness”[6,17-19]. Such a conceptualisation also suggests that the two may share similar features at the somatic, behavioural and cognitive levels[17,20,21], even though shyness is not pathological[17]. More specifically, it might be assumed that shy and socially anxious subjects also share similar features in terms of metacognitive beliefs and ruminative processes. An evaluation of whether rumination and metacognitive beliefs are associated with shyness could enrich the literature on the possible aetiological factors of shyness. Although it might be considered as a source of limited evidence to support this specific assumption, Vassilopoulos et al[22] suggested that during preadolescence, shyness might be correlated with post-event processing. However, no studies to date have explored the proposed a relationship between metacognitive belief, rumination and shyness in a sample of adults.

Based on the S-REF model[2], this study aims to explore the association between metacognitive beliefs, rumination and shyness in a non-clinical sample of adults. We hypothesised that higher levels of metacognitive belief and rumination would be associated with higher levels of shyness.

One hundred and three healthy subjects were recruited from the general population on the basis of the following inclusion criteria: At least 18 years old and fluent in Italian. In terms of exclusion criteria, individuals with personality disorders were excluded on the basis of a diagnostic interview conducted by psychologists who assessed demographic data, past or current emotional disorders, or psychological and/or psychopharmacological treatments. All participants provided informed consent.

Shyness was evaluated using the Revised Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale[23], a 14 item self-report scale. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate greater levels of shyness. The Revised Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale possesses good psychometric properties[24,25]. The official Italian translation of this scale by Marcone and Nigro[24] was used.

Rumination was measured by the Ruminative Response Scale[26], a 22 item self-report scale assessing the propensity to ruminate in response to depression. Respondents are required to indicate the degree to which they engage in a ruminative thinking style when they feel depressed. Each item is rated on a four-point scale ranging from one (almost never) to four (always). Higher scores indicate higher levels of rumination. This scale possesses good psychometric properties[27]. The English version of this scale was back-translated into Italian by a native Italian speaker who was not familiar with the questionnaire.

Metacognition was assessed using the Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire 30[28], a 30 item self-report instrument assessing individual differences in metacognitive beliefs, judgments and monitoring tendencies. Higher scores indicate greater levels of maladaptive metacognitive beliefs. The Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire 30 possesses good psychometric properties[28,29].

Anxiety levels were measured using the State Trait Anxiety Inventory form Y[30] for assessing trait anxiety. This form is a 40 item self-report scale in which participants rate the extent to which they experience various manifestations of anxiety. This form possesses good psychometric properties[30].

In order to evaluate the association between shyness, rumination and metacognition, Pearson’s correlation analyses were performed. Mediation models[31] were tested in order to evaluate the mediating role of rumination in the association between metacognition and shyness. In accordance with Baron and Kenny[31], a correlative analysis was used before evaluating the mediation effects to ensure that metacognition (independent variable IV), shyness (dependent variable DV) and rumination (mediator) correlated with each other. The mediation model was tested according to Baron and Kenny’s criteria[31], which assume that a fully- or partially-mediating relationship occurs when the relationship between the IV and DV is non-significant or still significant, respectively, after controlling for the effect of the mediator. In this study, the mediation model was performed using the SPSS macros for bootstrapping[32] as provided by Preacher and Hayes[33]. The indirect effect was tested using a bootstrapping procedure[32,33]. Mediation analyses were controlled for sex and anxiety. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.

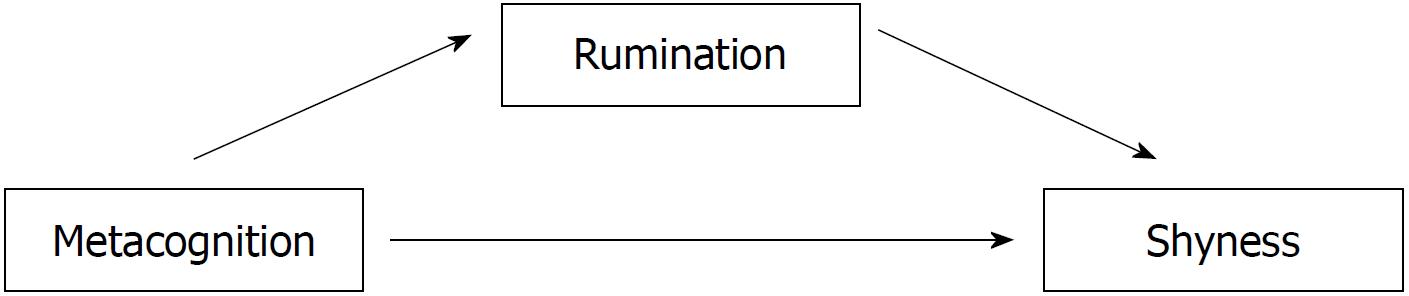

Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests indicated that the distribution of variables was normal. Sixty percent of the samples were female with an average age of 35.8 (SD ± 5.98) and a mean school education of 13.70 years (SD ± 3.66). Significant correlations were found between shyness, rumination and metacognition (Table 1). Rumination mediated the association between metacognition and shyness (Table 2 and Figure 1).

| STAI-Y anxiety | RCBS-shyness | MCQ-metacognition | RRS-rumination | |

| r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | |

| STAI-Y anxiety | 1 | |||

| RCBS-shyness | 0.022 (0.82) | 1 | ||

| MCQ-metacognition | 0.19 (0.05) | 0.223 (0.02) | 1 | |

| RRS-rumination | 0.071 (0.47) | 0.413 (< 0.001) | 0.734 (< 0.001) | 1 |

| B | SE | P | 95% BCaCI | ||

| Step 1 | |||||

| Sex | 2.32 | 2.43 | 0.34 | -0.49 | |

| Anxiety | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.46 | -0.49 | |

| Metacognition (IV) | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01-0.21 | |

| Shyness (DV) | |||||

| Step 2 | |||||

| Sex | 4.11 | 1.78 | 0.02 | 0.57-7.65 | |

| Anxiety | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.19 | -0.36 | |

| Metacognition (IV) | 0. 41 | 0.03 | < 0.001 | 0.33-0.48 | |

| Rumination (M) | |||||

| Step 3 | |||||

| Sex | 0.28 | 2.33 | 0.9 | -9.28 | |

| Anxiety | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.77 | -0.46 | |

| Metacognition (IV) | -0.08 | 0.06 | 0.23 | -0.28 | Total Effect: 0.11; BC: 0.01-0.22; P: 0.02 |

| Rumination (M) | 0.49 | 0.12 | < 0.001 | 0.23-0.75 | Direct Effect: 0-0.08; BC:-0.22-0.05; P: 0.23 |

| Shyness (DV) | Indirect Effect: 0.20; CB: 0.08-0.33 |

In this study, we examined the link between metacognition and shyness, as well as the mediation role of rumination. To our knowledge, no study has addressed this important issue, despite its obvious relevance and potential in reducing the negative effects of extreme shyness on human well-being. Rumination is known to be a crucial correlate of metacognition[2] and has recently been shown to be related to shyness and social anxiety[5,22]. Building on previous research, the core finding of the present study was the mediating role of rumination in explaining the relationship between metacognition and shyness. In this regard, rumination could be a helpful cognitive strategy for shy individuals.

The second important finding of this research was the significant association between metacognition and shyness. Such results are in accordance with previous studies on social anxiety[5], a similar construct to shyness. The results of this study seem to indicate that rumination as a mediator explains only a small percentage of variance in predicting shyness. Thus, future studies should investigate other possible factors that might also serve to mediate the relationship between metacognition and shyness, such as worry. In support of such reasoning, several studies have shown high levels of ruminative thinking about future difficulties and strategies by shy people in order to avoid anxiety-provoking situations (for a review, see Cowden[34]). In this negative circle, it seems that positive metacognitive processes induce the belief that worry could be useful to solve problems and help to prevent negative future events[35]. Thus, metacognition causes an increase in worry, and rumination becomes a problem. Worry could contribute to the development of negative perceptions of events that shy individuals avoid. Moreover, while shy individuals are worrying about the opinions of others and the impressions they make on others, such cognitive interference may result in them missing important information and cues from the environment, which could reduce their ability to execute the social skills needed to perform successfully during social situations.

It is also possible that metacognition directly influences shyness. Such data highlight the pressing need for a longitudinal investigation of these constructs to confirm the proposed relationship. The failure of shy individuals to respond appropriately in social situations is associated with the non-adaptive control of cognitive beliefs and type of metacognitive beliefs (e.g., the tendency for shy individuals to make internal attributions in response to interpersonal failures)[36], rather than to the usual schema’s content (e.g., the more general self-serving attribution bias to make external attributions for personal failures)[37].

The present research constitutes a novel contribution to the literature, given that the association between metacognition, rumination and shyness has not previously been addressed. We have only just begun to unravel the mechanisms through which metacognition and shyness are linked, and more research is needed to explore the relationship between these constructs.

Some limitations of the present work must be acknowledged. The first limitation is its cross-sectional design. A longitudinal study would be a more appropriate design for investigating the causal relationship between metacognition, rumination, shyness and their association over time. Secondly, although ours could be considered a sizeable sample, a larger one would have allowed us to go beyond our current level of analysis to explore, for example, gender or age differences. A third, more technical limitation of this study has to do with shared-method variance, as a result of using (only) self-administered instruments for variables of interest. However, as these variables are internal and subjective processes, self-report measures seemed appropriate. Furthermore, our study focused on metacognitive beliefs and did not investigate cognitive errors[38], and therefore should be considered exploratory.

We believe that the different patterns of associations that emerged have important practical implications for shy individuals. Starting from the position that shyness is neither a disease nor a psychiatric disorder[39], these results could be relevant in helping individuals to understand the nature and dynamics of shyness by addressing its cognitive components[40,41]. Carducci[42] and Sirikantraporn et al[43] have previously noted the value of examining the cognitive-related self-selected strategies used by shy individuals to deal with their shyness as a means of helping them to more effectively understand and respond to their shyness. Furthermore, with respect to the implications based on the results of the present study, the metacognitive model[44] should be a potentially valuable framework for improving the social skills of shy subjects. Based on the metacognitive model[44], the evaluation of metacognitive beliefs and ruminative thinking could be considered in shy subjects, given that this model is mainly focused on the modification or reduction of these aspects[44].

Metacognitive beliefs and rumination are correlated with social anxiety, which is located on a continuum of shyness. To our knowledge, no studies have explored the association between metacognitive beliefs, rumination and shyness in a non-clinical sample of adults.

To add to current knowledge about the association between metacognitive beliefs, rumination and shyness.

The main aim was to explore the association between metacognitive beliefs, rumination and shyness in a non-clinical sample of adults.

This was an observational study, comprising a sample of 103 healthy subjects recruited from the general population.

Shyness, rumination and metacognition were significantly correlated (P < 0.05). The relationship between metacognition and shyness was fully mediated by rumination (Indirect effect: 0.20; 95% bias-corrected and accelerated: 0.08-0.33). These results build upon previous research.

To our knowledge, no other study has investigated the link between metacognition and shyness, as well as the mediating role of rumination. The core findings of the study are: (1) The significant association between metacognition and shyness; and (2) the mediating role of rumination in explaining the relationship between metacognition and shyness. These results could have important implications for shy people. Although shyness is not a disease, the findings could be relevant in helping individuals understand the nature of their shyness by addressing its cognitive components.

Our research appears to indicate that future studies should longitudinally investigate the causal relationship between metacognition, rumination and shyness. Moreover, future studies should explore other possible factors, in addition to rumination, that might explain the relationship between metacognition and shyness.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Psychology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chakrabarti S, Hosak L, Seeman MV S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | Wells A, Matthews G. Attention and Emotion. A Clinical Perspective. Hove, UK: Erlbaum 1994; . [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wells A. Emotional disorders and metacognition: Innovative cognitive therapy. Chichester: Wiley 2000; . [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Spada MM, Caselli G, Wells A. A triphasic metacognitive formulation of problem drinking. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2013;20:494-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Spada MM, Caselli G, Nikčević AV, Wells A. Metacognition in addictive behaviors. Addict Behav. 2015;44:9-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wells A. Cognition about cognition: Metacognitive therapy and change in generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia. Cogn Behav Pract. 2007;14:18-25. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kashdan TB, Roberts JE. Social anxiety, depressive symptoms, and post-event rumination: affective consequences and social contextual influences. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21:284-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | de Jong-Meyer R, Beck B, Riede K. Relationships between rumination, worry, intolerance of uncertainty and metacognitive beliefs. Personal Individ Differ. 2009;46:547-551. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Moulds ML, Yap CS, Kerr E, Williams AD, Kandris E. Metacognitive beliefs increase vulnerability to rumination. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2010;24:351-364. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Callesen P, Jensen AB, Wells A. Metacognitive therapy in recurrent depression: a case replication series in Denmark. Scand J Psychol. 2014;55:60-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Caselli G, Gemelli A, Querci S, Lugli AM, Canfora F, Annovi C, Rebecchi D, Ruggiero GM, Sassaroli S, Spada MM. The effect of rumination on craving across the continuum of drinking behaviour. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2879-2883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ehring T, Watkins ER. Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. Int J. Cogn Ther. 2008;1:192-205. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 532] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mansueto G, Pennelli M, De Palo V, Monacis L, Sinatra M, De Caro MF. The Role of Metacognition in Pathological Gambling: A Mediation Model. J Gambl Stud. 2016;32:93-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gkika S, Wittkowski A, Wells A. Social cognition and metacognition in social anxiety: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2018;25:10-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nordahl H, Wells A. Testing the metacognitive model against the benchmark CBT model of social anxiety disorder: Is it time to move beyond cognition? PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wells A, Carter K. Further tests of a cognitive model of generalized anxiety disorder: Metacognitions and worry in GAD, panic disorder, social phobia, depression, and nonpatients. Behav Ther. 2001;32:85-102. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | McEvoy PM, Perini SJ. Cognitive behavioral group therapy for social phobia with or without attention training: a controlled trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:519-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC, Roberson-Nay R. Differentiating social phobia from shyness. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:469-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Battaglia M, Michelini G, Pezzica E, Ogliari A, Fagnani C, Stazi MA, Bertoletti E, Scaini S. Shared genetic influences among childhood shyness, social competences, and cortical responses to emotions. J Exp Child Psychol. 2017;160:67-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Battaglia M, Zanoni A, Taddei M, Giorda R, Bertoletti E, Lampis V, Scaini S, Cappa S, Tettamanti M. Cerebral responses to emotional expressions and the development of social anxiety disorder: a preliminary longitudinal study. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:54-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Buss AH. A theory of shyness. In Jones WH, Cheek JM, Briggs SR. Shyness: Perspectives on research and treatment. New York: Plenum Press 1985; 39-46. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Crozier R. Shyness as anxious self-preoccupation. Psychol Rep. 1979;44:959-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vassilopoulos SP, Brouzos A, Moberly NJ, Spyropoulou M. Linking shyness to social anxiety in children through the Clark and Wells cognitive model. Hellenic J Psychol. 2017;14:1-19. |

| 23. | Cheek JM. The Revised Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale (RCBS). Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA. 1983;. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Marcone R, Nigro G. La versione italiana della Revised Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale (RCBS 14-item). BPA. 2001;33-40. |

| 25. | Vahedi S. The factor structure of the revised cheek and buss shyness scale in an undergraduate university sample. Iran J Psychiatry. 2011;6:19-24. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1786] [Cited by in RCA: 1868] [Article Influence: 54.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nolen-Hoeksema S, Davis CG. “Thanks for sharing that”: ruminators and their social support networks. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77:801-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wells A, Cartwright-Hatton S. A short form of the metacognitions questionnaire: properties of the MCQ-30. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:385-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 696] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Spada MM, Mohiyeddini C, Wells A. Measuring metacognitions associated with emotional distress: Factor structure and predictive validity of the Metacognitions Questionnaire 30. Pers Individ Dif. 2008;45:238-242. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL. State-trait anxiety inventory for adults: sampler set: manual, test, scoring key. Mind Garden, 1983. . |

| 31. | Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173-1182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48287] [Cited by in RCA: 31515] [Article Influence: 829.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6057] [Cited by in RCA: 4668] [Article Influence: 203.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36:717-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9867] [Cited by in RCA: 7149] [Article Influence: 357.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Cowden CR. Worry and its Relationship to Shyness. N Am J Psychol. 2005;7. |

| 35. | Laugesen N, Dugas MJ, Bukowski WM. Understanding adolescent worry: the application of a cognitive model. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2003;31:55-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Alfano MS, Joiner TE, Perry M. Attributional style: A moderator of the shyness-depression relationship? J Res Pers. 1994;28:287-300. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Miller DT, Ross M. Self-serving biases in the attribution of causality: Fact or fiction? Psychol Bull. 1975;82:213. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1383] [Cited by in RCA: 1443] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Koydemir S, Demir A. Shyness and cognitions: an examination of Turkish university students. J Psychol. 2008;142:633-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Carducci BJ. Shyness: A bold new approach. New York: Harper Perennial 2000; . |

| 40. | Crozier WR, Alden LE. Coping with shyness and social phobia: A guide to understanding and overcoming social anxiety. Oneworld Publications, 2009. . |

| 41. | Henderson L. The compassionate-mind guide to building social confidence: Using compassion-focused therapy to overcome shyness and social anxiety. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Compassion 2011; . |

| 42. | Carducci BJ. What shy individuals do to cope with their shyness: a content analysis and evaluation of self-selected coping strategies. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2009;46:45-52. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Sirikantraporn S, Jitnarin N, Jongjumruspun B, Carducci B. A principal component analysis of the Thai Revised Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale and qualitative evaluation on how Thai people cope with shyness: A Multi-method replication and cultural extension. International Psychology Bulletin. 2018;22:14-24. |

| 44. | Wells A. Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. New York: The Guilford Press 2009; . |