Published online Sep 20, 2018. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v8.i3.79

Peer-review started: May 18, 2018

First decision: June 15, 2018

Revised: June 29, 2018

Accepted: July 10, 2018

Article in press: July 10, 2018

Published online: September 20, 2018

Processing time: 125 Days and 20.7 Hours

Illness narratives are stories of illness told by patients with chronic illness. One way of studying illness narratives is by considering illness narrative master plots. An examination of illness narrative master plots has revealed the importance of psycho-emotional information contained within the story that is told. There is a need for research to capture this information in order to better understand how common stories and experiences of illness can be understood and used to aid the mental well-being of individuals with chronic illness. The current editorial provides a suggestion of how this is possible. This editorial identifies that stories can be “mapped” graphically by combining emotional responses to the illness experience with psychological responses of the illness experience relating to hope and psychological adaptation. Clinicians and researchers should consider the evidence presented within this editorial as: (1) A possible solution for documenting the mental well-being of individuals with chronic illness; and (2) As a tool that can be used to consider changes in mental well-being following an intervention. Further research using this tool will likely provide insights into how illness narrative master plots are associated together and change across the course of a chronic illness. This is particularly important for illness narrative master plots that are difficult to tell or that are illustrative of a decline in mental well-being.

Core tip: This editorial provides implications for how illness narratives can be assessed. It identifies how and why the assessment is useful and crosses the academic disciplines of medical sociology and psychology.

- Citation: Soundy A. Psycho-emotional content of illness narrative master plots for people with chronic illness: Implications for assessment. World J Psychiatr 2018; 8(3): 79-82

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v8/i3/79.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v8.i3.79

Illness narratives reflect stories told by patients about their experience of illness. The term narrative is generally regarded as including at least “one character who experiences one event” but most narratives will have multiple events associated together in a suggested causal sequence within a particular setting[1]. Health care professionals (HCP) can use illness narratives as an effective vehicle to help behaviour change in patients [2]. Being able to share narratives with HCPs enables a patient’s agency, self-esteem and self-respect[3]. However, it is acknowledged that psychosocial, political and environmental factors influence a patients’ shared expression[4-6].

There are clear reported benefits of using illness narratives for the purpose of rehabilitation compared to traditional rehabilitation approaches including, a reduced counter argument against advice given to patients from HCPs and greater illustration of pathways or strategies for managing illness[7]. The use of illness narratives can also reduce interactions which lack emotional support and create barriers to behaviour change[3]. This is important as emotional support is consistently associated with more positive psychological adaptation to chronic illness, whereas negative experiences of support may hinder cognitive processes associated with psychological adaptation and mental well-being[8]. The term mental well-being is defined as defined as satisfaction, optimism and purpose with life, a sense of mastery, control, belonging, and perceiving social support[9].

Illness narratives contain a plot that often contains a beginning, middle and end[2]. Illness narrative master plots are common stories of illness that use a distinct or common plot as a response to illness, for an overview of 13 common illness narrative master plots see Soundy et al[10]. The master plots illustrate the impact of an illness on a patient focusing on key psychological attributes including emotions, adaptation and hope. Each master plots references time indicating psychological adaptation to what life was like in the past, what it is currently like and what it could be like in the future[10,11]. Different and seemingly contrasting illness narrative master plots can be told simultaneously by a patient, this is an important process as it reflects key stages in illness adaptation[11].

Illness narrative master plots generated out of loss and change from illness symptoms are some of the most important and critical stories told by people with chronic illness. They are important because certain illness narrative master plots can be difficult to hear or can be denied by others[12]. HCPs need to have an awareness of the psychological meaning behind a patient’s narrative master plots. However, evidence has suggested that further understanding is needed[3] and that clinical practice may prevent or inhibit this, e.g., as empathy can be lost through training[13].

Specific emotions felt by a patient following chronic or palliative illness or symptom change will clearly influence subsequent their decision making and responses to illness[14]. Specific emotions can be related to specific cognitive processes, for instance, fear may be associated with a low level of perceived control over one’s situation whereas anger can be associated with a high level of perceived control. It has been identified during times of change, including diagnosis or symptom change that patients with chronic illness express far more unpleasant than pleasant emotions. For instance, a recent review[15] that grouped emotional expressions as part of the experience of living with a chronic illness only identified one consistently pleasant emotion; relief (identified in 16/47 studies). Far more apparent were unpleasant activated emotions such as panic, fear or being scared (19/47), anger (15/47) or frustration (18/47 and deactivated unpleasant emotions such as sadness (12/47), depression (12/47), pessimism (7/47), or feeling upset (14/47). The impact of emotions on a patient’s responses must have further consideration. If patients feel overwhelmed with fear or worry and powerless within the experience of illness the cognitions expressed by them may be more likely to lead to a succumbing illness response, dominated by an inability to access coping resources[16].

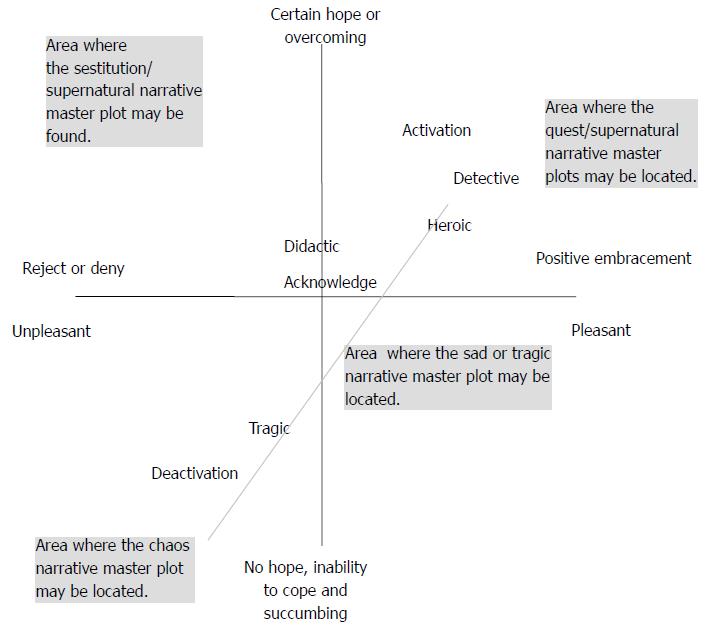

Research[11] has suggested that emotions, hope and adaptation can be assessed and used to represent the distinct narrative master plots by using the circumplex model of affect[17,18] to capture emotions alongside the hope and adaptation scale[19]. The latter scale requires the patient to identify what for them is perceived as most difficult aspect of their life to adapt to following an illness onset or change. This is then considered in relation to their own ability to adapt to what has happened and hope for change. These two brief scales have been combined together to represent a model of emotion, adjustment and hope[15]. As narrative master plots can be represented by particular psycho-emotional components[11], it is possible to suggest that these combined tools and model can be used to map illness narrative master plots (Figure 1).

By mapping narrative master plots HCPs and researchers may be able to capture a patient’s underlying psychological and emotional responses to illness. This enables a consideration of how; plots vary across time, what plots may be dominant for particular conditions or time following illness symptom change and how, and if, particular master plots are associated with one another. There is also a need to use the understanding of emotive and cognitive components of different master plots to target psychological interventions, e.g., the emotional reaction expressed by a patient may be that of fear of what is happening which may cause them to want to escape or deny their circumstances[20]. In addition, understanding the cognitive processes of adaptation and hope may provide a point of discussion from where psychological intervention can begin.

HCPs should be able to map patient’s response on a session by session basis, e.g., HCPs by their responses have an opportunity to aid a patient’s mood. For instance, a poor choice of words and an inability to listen may generate negative moods from interactions and be regarded as a perceived threat by an HCP. The mapping of illness narratives may provide greater clues to how particular narratives dominant or become dominant in a patient.

There is a need to consider how illness narratives are linked to one another and if targeting a particular aspect of the inventories is more effective. Further, there is a need to consider how changeable narratives are and if certain master plots are more resistant to change. Using tools identified above, narratives can be established and the meaning behind the narrative can provide a greater understanding and insight to the mental well-being of the patient.

Mapping an individual’s master plots and understanding the psycho-emotional content of them may provide an essential tool for understanding the mental well-being of patients. Further research is needed in order to clarify and consider these points further.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Hosak L, Pasquini M S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Bian YN

| 1. | De Graff A, Sanders J, Hoeken H. Characteristics of narrative interventions and health effects: A review of the content, form, and context of narratives in health-related narrative persuasion research. RCR. 2016;4:88-133. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Elliott J. Using narrative in social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Narrat Inq. 2005;15:421-429. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Lucius-Hoene G, Thiele U, Breuning M, Haug S. Doctors’ voices in patients’ narratives: coping with emotions in storytelling. Chronic Illn. 2012;8:163-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee AM, Poole G. An application of the transactional model to the analysis of chronic illness narratives. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:346-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Faircloth CA, Boylstein C, Rittman M, Young ME, Gubrium J. Sudden illness and biographical flow in narratives of stroke recovery. Sociol Health Illn. 2004;26:242-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Haidet P, Kroll TL, Sharf BF. The complexity of patient participation: lessons learned from patients’ illness narratives. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62:323-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Boinon D, Sultan S, Charles C, Stulz A, Guillemeau C, Delaloge S, Dauchy S. Changes in psychological adjustment over the course of treatment for breast cancer: the predictive role of social sharing and social support. Psychooncology. 2014;23:291-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | National Health Service Scotland. Mental health and wellbeing. Available from: http://www.healthscotland.com/mental-health-background.aspx. |

| 10. | Soundy A, Smith B, Dawes H, Pall H, Gimbrere K, Ramsay J. Patient’s expression of hope and illness narratives in three neurological conditions: a meta-ethnography. Health Psychology Review. 2013;7:177-201. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Soundy A, Roskell C, Stubbs B, Collett J, Dawes H, Smith B. Do you hear what your patient is telling you? Understanding the meaning behind the narrative. Wayahead. 2014;18:10-13. |

| 12. | Norrick N. The dark side of tellability. Narrat Inq. 2005;15:323-343. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Soundy A, Smith B, Cressy F, Webb L. The experience of spinal cord injury: using Frank’s narrative types to enhance physiotherapy undergraduates’ understanding. Physiotherapy. 2010;96:52-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lerner JS, Li Y, Valdesolo P, Kassam KS. Emotion and decision making. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:799-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 993] [Cited by in RCA: 721] [Article Influence: 65.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Soundy A, Roskell C, Elder T, Collett , J , Dawes , H . The psychological processes of adaptation and hope in patients with multiple sclerosis: a thematic synthesis. OJTR. 2016;4:22. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Soundy A, Condon N. Patients experiences of maintaining mental well-being and hope within motor neuron disease: a thematic synthesis. Front Psychol. 2015;6:606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Posner J, Russell JA, Peterson BS. The circumplex model of affect: an integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 2005;17:715-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1643] [Cited by in RCA: 843] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Russell JA. A circumplex model of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39:1161. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7547] [Cited by in RCA: 7842] [Article Influence: 174.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Soundy A, Rosenbaum S, Elder T, Kyte D, Stubbs B, Hemmings L, Roskell C, Collett J, Dawes H. The hope and adaptation scale (HAS): Establishing face and content validity. OJTR. 2016;4:76-86. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fredrickson BL. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1367-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1436] [Cited by in RCA: 1236] [Article Influence: 58.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |