Published online Sep 22, 2016. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i3.381

Peer-review started: April 15, 2016

First decision: May 19, 2016

Revised: May 28, 2016

Accepted: August 11, 2016

Article in press: August 13, 2016

Published online: September 22, 2016

Processing time: 159 Days and 17 Hours

In this paper we illustrate the potential of the repertory grid technique as an instrument for case formulation and understanding of the personal perception and meanings of people with a diagnosis of psychotic disorders. For this purpose, the case of James is presented: A young man diagnosed with schizophrenia and personality disorder, with severe persecutory delusions and other positive symptoms that have not responded to antipsychotic medication, as well with depressive symptomatology. His case was selected because of the way his symptoms are reflected in his personal perception of self and others, including his main persecutory figure, in the different measures that result from the analysis of his repertory grid. Some key clinical hypotheses and possible targets for therapy are discussed.

Core tip: The repertory grid measures indicated that the patient’s meaning system was strongly articulated around a very negative view of self, and by symptomatic constructs related to fear, anxiety, sense of loneliness, and perceived aggressiveness in others. Furthermore, constructs related to hostility dominated his perception of his persecutory figure and also of his parental figures. Based on this appraisal, the case formulation was suggested as a focus for psychotherapy to enhance his self-esteem and deal with family conflicts.

- Citation: García-Mieres H, Ochoa S, Salla M, López-Carrilero R, Feixas G. Understanding the paranoid psychosis of James: Use of the repertory grid technique for case conceptualization. World J Psychiatr 2016; 6(3): 381-390

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v6/i3/381.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v6.i3.381

Psychotic disorders are complex conditions with a wide range of clinical symptoms. One of the central psychotic experiences is persecutory delusions, which are present in over 70% of early psychotic patients[1], and which are accompanied by many clinically important symptoms such as anxiety and depression[2]. Despite the common administration of antipsychotic medication, more than half of patients still have persistent positive symptoms that interfere with their daily functioning[3,4]. In this context of drug-resistant cases, the use of psychotherapy, with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) the most widely studied, is of increasing interest and importance, and is recommended either as an adjuvant or even an alternative treatment. To this effect, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated the efficacy of CBT in reducing symptom severity in these cases[5]. In addition, one randomized controlled trial demonstrated similar results for cases not taking antipsychotic drugs[6].

In cognitive models of psychosis and other mental disorders, an essential element for planning psychological therapy is the use of case conceptualization. From a person-based approach to psychosis[7], paranoid psychotic symptoms cannot be studied in isolation because the distress experienced by these patients is not a direct consequence of psychotic symptoms. Rather, it is mediated by the meaning patients ascribe to them. With this approach more attention is paid to personal meanings than to symptoms when developing each patient’s case conceptualization.

From a more general perspective, this focus on the subjective construction of the symptoms and problems experienced by the client was previously highlighted by personal construct theory (PCT)[8]. This theory sees psychological activity as a subjective meaning-making process for the events people encounter in life[9]. Thus, the person’s cognitive system is formed by a complex network of bipolar dimensions of meaning, interdependent and hierarchically organized, denominated personal constructs (as opposed to theoretical constructs), such as “friendly-hostile”. This system of constructs is used to interpret the person’s experience and to organize his or her actions.

In PCT, case conceptualization is understood as a way to see the world through the patient’s eyes[10].To study personal views of the world, the most widely used method is the Repertory grid technique (RGT). It allows us to access the idiosyncratic meanings of the person about self and others, in his or her interpersonal world. Also, it yields some measures regarding the cognitive structure of the subject. Both sources of information have interesting clinical implications: They allow the therapist to formulate clinical hypotheses and identify possible targets for therapy[11]. In addition, in a review by Freeman et al[2], perceptions of self and others have been linked to the development and maintenance of persecutory delusions, as well as being proposed as important targets for therapy.

Despite its possibilities as an instrument for the detailed exploration of the individual’s belief system to be employed for case conceptualization, little use is made of the RGT in common psychiatric practice and psychotherapy, and no recent studies have been found involving cases with paranoid psychotic symptoms. This is even more surprising given the line of research led by Bannister in the 1960s and 1970s[12] (although they were using another type of grid with provided rather than elicited personal constructs).

In this article, we present the possibilities for the application of the RGT toward the understanding of paranoid psychosis, showing the sense that symptoms can have for the person with schizophrenia. To this end, we have selected the case of James (fictitious name), a man diagnosed with schizophrenia and personality disorder, who presents severe persecutory delusions that have not improved with medication. He was one of the first patients to participate in a Spanish clinical trial based in Metacognitive Training (MCT+) for psychosis by Moritz et al[13]; in the initial evaluation, a battery of instruments was administered, including instruments that assess psychophatology and the RGT. The main indices obtained from the RGT are described and used to understand his personal meanings about himself and others at the delicate moment when his persecutory delusions are very intrusive. Possible clinical hypotheses derived from this analysis, and targets for the therapeutic process of James, are discussed.

James is a Spanish man 25 years of age who lives with his parents and is unable to study or work although he completed high school studies. He reports a relationship with a girl, Ana, at the current moment, who lives in a distant part of Spain. He refers to her as his girlfriend but their only contact has been by internet and telephone.

He has a diagnosis of schizophrenia and personality disorder not otherwise specified. The disturbances started 2 years ago, and the last psychotic episode occurred 10 mo before the present assessment, for which he had to be hospitalized. Since this last hospitalization, he has been experiencing persecutory delusions and auditory hallucinations that have not been reduced, despite taking antipsychotic medication, olanzapine 20 mg/d and aripiprazole 15 mg/d, last one administrated monthly as depo.

As relevant background to the psychotic symptoms, James had a relationship two years ago with another girl, Mary, which lasted eighteen months. During the assessment, he told us that it was a good relationship most of the time. He also stressed that both of them felt the lack of support from other people (“We were both alone, we had in common that we had no one else, and we relied on each other”). At the end of the relationship, James uploaded a song on line in which he talked about Mary and their relationship, and he also made comments on social networks about the girl, resulting in conflict with Mary and her family and friends, and turning all of them against him. In this context, James developed intense fears of the girl and her relatives, which culminated in a psychotic crisis experienced 10 mo before this assessment.

Since then, James says that he lives in fear every day, convinced that his ex-girlfriend and her relatives seek to harm or even kill him, even when he recognizes not having had any contact with them for months. He has a general feeling of being threatened and persecuted, being very alert to signs in the environment, which makes him afraid to go outside. His psychotic experiences seem to increase at night when he hears noises at his window. He is afraid that they could be caused by his persecutors, so most nights he has problems falling asleep. From time to time, he also presents auditory hallucinations of which he is unaware, hearing voices on the street, which always have threatening content, referring to hurting or killing him.

Regarding the relationship with his parents, he says that the family atmosphere is not good, there having been severe conflicts since adolescence, when James had episodes of aggression toward his parents. James maintains a discourse greatly focused on his paranoid ideas, and when he talks about his fears at home he says he feels unheard and slighted, and that he has received aggressive and dismissive responses. He experiences family life as hostile, and describes having suffered episodes of aggression from his father not only in the past but also recently. He also notes that since the psychotic crisis, he has lost the few friends he had, feeling very alone and with little support.

In the Metacognitive Training study in which James is enrolled, a battery of instruments was administered in two sessions before the beginning of the therapy.

The instruments assessing psychopathology, shown in Table 1, were administered in the first session. James’s scores on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Spanish adaptation of Peralta et al[14], and the Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales (PSYRATS), Spanish adaptation by González et al[15], showed a high severity for the positive symptoms. In addition, on PANSS items related to passive social withdrawal and active social avoidance the scores indicate moderate-severe social isolation, which is associated with his suspiciousness and persecutory fears. He also presented severe depressive symptomatology, as measured with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), Spanish adaptation by Sanz, Perdigón et al[16].

| Raw scores | |

| PANSS positive | 23 |

| P1: Delusions | 6 |

| P6: Suspiciousness/persecution | 6 |

| PANSS negative | 17 |

| PANSS general psychopathology | 37 |

| PSYRATS delusions | 21 |

| PSYRATS hallucinations | 33 |

| BDI-II | 32 |

The severity of his psychopathology could also be observed during the second interview, when the repertory grid was administered. He was very cooperative and talkative, but he was also invaded by his delusions and made repeated verbalizations about them and the suffering that they brought him (“I’m scared. Before coming here I heard a man in a bar talking about killing me”).

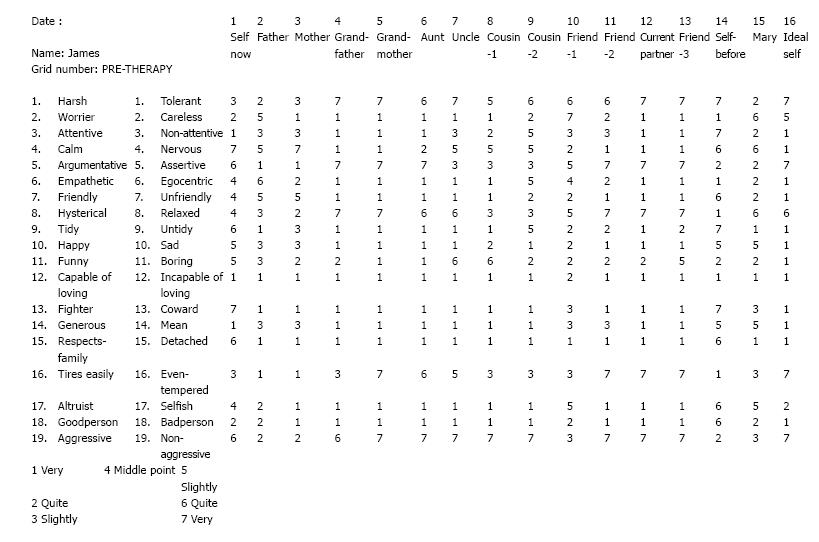

The RGT is a structured interview exploring the patient’s personal meanings. The first phase is the selection of elements, which represent a sample of the most significant people for the patient. In the case of James, 17 elements were chosen. Four of them were provided by the clinician according to their possible clinical implications: “self now”, “ideal self” (which represents how he would like to be), “self before the psychotic crisis”, and the “non-grata person”, which represents a person he does not like (for James, this was his ex-girlfriend, his main persecutory figure). The remaining elements, elicited by James, were his parents, six members of the extended family who live far away but for whom he felt much appreciation (maternal grandparents, two uncles, and two cousins), two good friends from the time before the psychotic crisis, Ana, identified by him as his current partner, and a friend of his partner’s with whom he often talks. The selected items are recorded in the upper part of the protocol of the grid (Figure 1) defining the columns, the first column for the “self now” and the last for the “ideal self”.

In the second phase, constructs are not provided by the clinician (like items in nomothetic research); rather, they are elicited directly from the person evaluated as a way to express his or her personal meanings. Personal constructs are elicited using the dyadic method, which consists of asking the subject about similarities and then differences in each pair of elements in terms of their perceived personality or character traits. For example, the first question for James was: “In terms of their personality, in which way would you say your mother and father are alike?” James answered, “Both of them are harsh”. This answer constitutes one pole of the first construct, so to obtain the other pole we asked “What would be the opposite of harsh for you?” and the answer was “tolerant”. Thereby, the first construct (“harsh vs tolerant”) was obtained and more similarity and difference questions were made for this and other pairs of elements. Elicited constructs were written down by the interviewer in the horizontal entries of the grid (Figure 1). After 19 constructs were obtained from James he started to repeat many constructs and showed fatigue. This is usually the time to end the elicitation process, which is known as the “saturation point”.

The last phase is the rating of the elements. Each element is assigned a value in a seven-point Likert-type scale for each construct. Taking as an example the cited construct, 1 means “very harsh”, 2 “quite harsh”, 3 “slightly harsh”, 4 “middle point”, 5 “slightly tolerant”, 6 “quite tolerant”, and 7 “very tolerant”.

Once the grid data matrix was filled (see James’s grid in Figure 1), the administration process ended, and the data were ready to be analyzed qualitatively or quantitatively, for which there is software available, the GRIDCOR, with a manual to guide interpretation of the data[17]. This software allows synthesizing and analyzing the great amount of information reflected in the grid using different statistical methods.

From the data of the grid we may grasp the personal views of James about himself. To do so, we should focus on the constructs in which James rates himself with extreme values (scores of 1-2 and 6-7). Once obtained, we can narratively formulate his self-definition: “I am a very attentive, generous person, with a great capacity to love. But I’m also very nervous and very cowardly. I also consider myself quite a good person, concerned and assertive, but I am also quite messy and detached from my family, for whom I feel I have little respect”.

We identify what James values about himself by finding congruent constructs in his grid. These are the constructs where the elements “self now” and “ideal self” are rated in the same pole, dimensions for which James does not wish any change. We found six such constructs: Attentive, assertive, capable of loving, generous, good person, and non-aggressive.

In contrast, discrepant constructs reveal aspects that James does not like about himself and which he would like to change. These are constructs in which the “ideal self” is rated at the opposite pole to the “self now”. These discrepant constructs can be also expressed narratively:“Contrary to what I am (harsh, nervous, messy, sad, boring, cowardly, detached, and someone who tires easily), I would like to be tolerant, quiet, happy, funny, a fighter, and even-tempered”.

James’s congruent constructs are his “strong points”, those which might be central to his identity. Additionally, they may be seen as resources to validate and protect during the therapy process. However, James presents more discrepant than congruent constructs (eight to six), which could be a reflection of his current life moment in which he lives dominated by fears that stem from his persecutory delusions (“I would like to be a fighter, but I am a coward”), in a state of suffering and dissatisfaction with himself (“I would like to be happy and quiet, but instead I am sad and nervous”).

The GRIDCOR program outputs many quantitative measures that explain different aspects of how the patient construes himself and others, and also about the structure of his cognitive system. In the case of James, the most significant indices are shown in Table 2.

| Self-construing | Cognitive structure | ||

| Self-ideal distance | 0.5 | PVAFF | 54.11% |

| Self-others distance | 0.4 | Polarization | 60.53% |

| Ideal-others distance | 0.25 |

Construing self and others: Various aspects of the self can be evaluated taking the Euclidean distances between the elements “self now”, “ideal self” and “others” (an artificially generated element taking into account the average of the scores of all elements but “self now” and “ideal self”).

Self-ideal differentiation: The discrepancy in the ratings of the elements “self now” and “ideal self” can be considered as a measure of self-esteem, since by comparing these two elements the patient is evaluating himself on his own terms. High differentiation (e.g., d > 0.32) is usually taken as indicative of low self-esteem. This is the case with James: He feels very far away from the way he would like to be and he therefore feels great dissatisfaction with himself and serious distress. This finding matches with the self-definition of James, with many discrepant constructs, and with the clinical observations made during the assessment process.

Self-others differentiation: The discrepancy between self and others becomes an index of how people see themselves as different (or similar) with respect to the other elements in the grid. This differentiation is considered as a measure of perceived social isolation. High differentiation (e.g., d > 0.35) is an indication that a person experiences himself or herself as different from others, feeling that he or she shares few features with other people.

James presented high perceived social isolation, viewing himself as very different, which is compatible with feeling like “the weird guy”, accompanied by notable feelings of loneliness.

Ideal-others differentiation: The discrepancy between the ideal self and others is considered as an index of the degree of perceived adequacy of others. High dissimilarity (e.g., d > 0.28) means that the person has great dissatisfaction with others, while a lower score suggests a positive perception of them, as was the case with James. For a wider perspective, we can take into account his self-esteem, which is very low and negative, with others being closer to his ideal self than his current self; they are the “good ones”.

Self-construction profile: Five different self-construction profiles can be identified taking into account the joint interpretation of the three differentiation indices explored: Positivity, superiority, negativity, depressive isolation, and resentment profiles.

The conjoint interpretation of the three indices of James suggests a depressive isolation profile. This profile represents the combination of having a negative view of oneself, high perceived social isolation, and a positive perceived adequacy of others. This combination suggests that James views himself in negative terms and different from others, as if he was saying: “The others are great, but not me. I am the only one who is weird”. This profile usually applies to depressive patients and people with other psychiatric categories who manifest hopelessness, which is congruent with James’s depressive symptoms.

Interpersonal cognitive differentiation: Interpersonal cognitive differentiation refers to the extent to which a person can construe his or her social experiences from different points of view. The more differentiated a cognitive structure is, the more meaningful dimensions are available to the person to perceive and understand the behavior of others.

Several measures have been proposed to assess cognitive differentiation, but the percentage of variance accounted for by the first factor (PVAFF) resulting from the factor analysis is the one with the strongest reputation. This percentage indicates the importance or weight of the main dimension of meaning. It is estimated that a low PVAFF indicates a differentiated cognitive structure, favoring multidimensional thinking and allowing other dimensions to play relevant roles in the way the subject construes, while a high PVAFF indicates low cognitive differentiation, with a tendency to one-dimensional thinking. James’s score indicates a cognitive structure with low differentiation, with one dimension which plays the main role for the construction of himself and the others.

Polarized thinking: Polarization refers to the extent to which a person construes reality in an extreme way, and it is considered as a measure of cognitive rigidity. It is computed as the percentage of extreme scores in the grid. High percentages are indicative of a polarized structure. This score is very high in the case of James, suggesting a very rigid cognitive structure, with a tendency to construe himself and others in a dichotomous way.

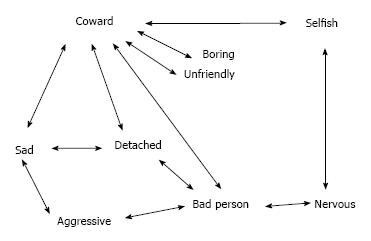

Centrality of symptomatic constructs: The variance accounted for by each construct in the grid data matrix is calculated with Bannister’s[18] Intensity score, which is based on the strength of the correlations with the other constructs. Thus, those constructs with the highest intensity scores tend to be the ones with greater weight or importance in the cognitive system. When these constructs express aspects which can be considered as symptomatic, then potential difficulties for change in the therapeutic process may appear. For James, five constructs are the most intense or central to his cognitive system: “coward vs fighter”, “aggressive vs non-aggressive”, “unfriendly vs friendly”, “tires easily vs even-tempered” and “nervous vs calm”. Analyzing their content, most of these core constructs could be considered as symptomatic, reflecting his emotional experience of fear and anxiety, and his perception of threat in others, both in the context of the persecutory delusions. The construct “coward vs fighter” is central to the sense of identity of James. Additionally, it does have a very high percentage of polarization (87.50%). Checking his grid raw data matrix (Figure 1), we observe that he considers himself as the only element who is a “coward”, while all the others are perceived as “fighters” (as he would like to be). Clinically, this construct might be related to the suffering and permanent sense of fear and alertness that invades his personal life.

To analyze the identity implications of this construct, the correlation matrix among constructs can be used to explore its personal meaning in the context of his cognitive system. In Figure 2, the network of constructs associated with the pole “coward” is represented. All the constructs that are associated with it have negative connotations. The construct pole “coward” is strongly associated, by this order, with the poles “detached” (r = 0.94), “boring” (r = 0.90), “selfish” (r = 0.83), “sad” (r = 0.81), “bad person” (r = 0.79) and “unfriendly” (r = 0.61). Therefore, this highly interrelated meaning configuration articulated around the core construct “coward vs fighter” helps us to understand how invalidating it must have been for James to experience intense fears (such as those caused by the perceived threat of others). We may infer here a massive invalidation of his most central aspirations (becoming “fighter”, “funny”, “altruist”, “happy”, a “good person”, “friendly”, and someone who “respects his family”). In PCT, this invalidation of core constructs is linked to intense negative emotions.

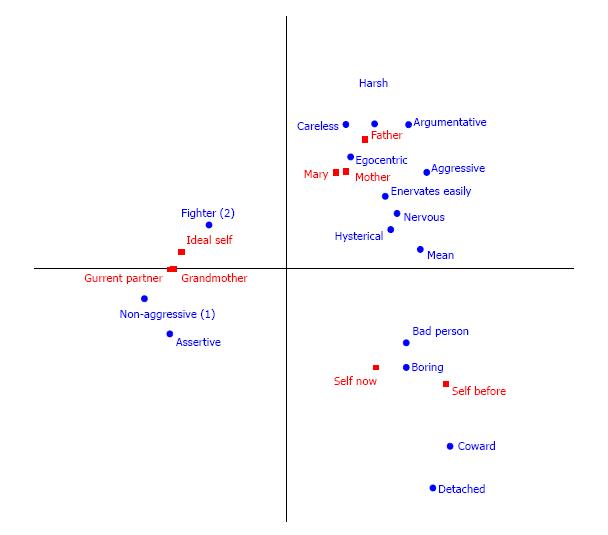

A graphic display of the main axes of construction: The GRIDCOR program employs Correspondence Analysis, a multivariate statistical technique similar to principal component analysis, in order to simultaneously compute both constructs and elements expressed in the grid data matrix. It aims to represent the main dimensions of meaning employed by the subject in order to understand his interpersonal world. Each axis or dimension is composed of both elements and constructs with their corresponding loads (which varies across axes).

In the case of James, as mentioned before, the first factor explained 54.11% of variance while the second one accounted for 16.54%. Taken together, these two axes are responsible for 70.66% of the variance in the grid data. The GRIDCOR software yields a graph placing both axes orthogonally, creating a two-dimensional space, which allows us to get an approximate picture of how James perceives himself and others from his main dimensions of meaning (Figure 3). As explained before, each axis represents a dimension of meaning, comprising a particular combination of specific constructs and elements, which are arranged along the axis, being allocated the ones that account for major weight in each axis at the extremes, and around the central area the ones with less weight in that dimension of meaning. In this graph, the final allocation of both constructs and elements results from the combination of the dimensions of meaning of both axes, the first axis represented in the horizontal (abscissa) plane and the second axis in the vertical (ordinate). In this case, for instance, the extremes of the first axe are delimited by the elements “self before” and the “ideal self” or “current partner”, whereas the extremes of the second axis are represented by “father” and “self now”. The selected constructs and elements that appear in the graph account for the major weight in both axes, and, therefore, it represents the meanings that James gives the most importance to in his view of his interpersonal world, according to grid data. From the distribution of people and meanings in this graph we may derive three different groupings with which James categorizes and interprets his interpersonal world.

James’s group, the lonely guy: Me and my “self before the crisis”. According to his grid, James perceived his current and past selves in negative terms (“coward”, “detached”, and “boring”), different and far from other people, reflecting his experience of self-isolation. Looking at the direct ratings in the grid, the only notable difference is that his current self is now seen as quite a “good person” while the self before the crisis is rated as quite a “bad person”. This could be an important aspect to explore in the therapy process to understand the meanings of this change for James.

The group of the good ones: Where James wants to belong. The ideal self of James is situated in an opposite quadrant, with his current partner and his grandmother. Although they do not appear in the graph due to lack of space and lesser variance loading, most of the other elements are located there as well. All the constructs with positive connotations appear there; James would like to be a “fighter”, which would imply also being “happy” and “respectful of family”, as others are perceived. Another constellation of constructs in this area is related to a desired change in the anxiety of James: He would like to become “even-tempered”, “quiet” and “calm”, like the others.

The threatening group: The parents and the persecutory figure. In this group we find Mary, his ex-girlfriend, whom he identifies as one of his main persecutors. His parents, with whom he has had many severe conflicts and from whom he feels little support, are there as well. Unexpectedly, these three people are located very close to each other. It may be seen that James gives meaning to them mainly in terms of a constellation of constructs with hostile content (“harsh”, “argumentative”, “aggressive”, and as people who “tire easily”).

In this article, the main objective was to illustrate how the RGT can provide clinicians with a systematic portrayal of the personal views of a patient with paranoid psychotic symptoms. This approximation might help in uncovering a patient’s personal meanings, and their relationship with symptoms, in order to enhance case formulation and identify therapy targets. We can also focus on the repertory grid indices found for James and contrast them with the current literature about psychosis. His self-definition and self-construction profile denote low self-esteem, with many negative evaluations about the self, which correspond to a set of discrepant constructs (“I am harsh, nervous, messy, sad, boring, a coward…”). Both low self-esteem and negative self-evaluations have been associated with the development and maintenance of positive symptoms[19,20]. More specifically, paranoid delusions have been linked to reflections of specific negative evaluations about the self[21]. Similarly, the high perceived social isolation reflected in James’s grid seems to be common in people with early psychosis, along with depressive symptoms[22]. Effectively, depression is common in psychotic patients, and following acute psychosis it may be a psychological response to the apparently uncontrollable life event that psychosis episodes represent for patients[23].Furthermore, depression can be a contributing factor in the maintenance of persecutory delusions[24].

A first clinical hypotheses derived from these findings is that the negative self-concept and depressive isolation profile of James play a significant role in his paranoid symptoms. He would benefit from therapy having as a target the enhancement of his self-esteem, reconstructing his discrepant constructs and protecting his congruent constructs from further invalidation, which could be expected to have a positive effect on his paranoid delusions as well as on his depressive symptoms. Another important target would be ways to help James feel integrated with others, which might also have a positive effect on his depressive symptomatology.

At this point some of the results derived from the analysis of the relationships among James’s personal constructs must be taken into consideration. First, we have to remember that some of these discrepant and symptomatic constructs for James constitute part of his identity, and being a “coward” and “detached” has many negative implications in his cognitive system. From the perspective of PCT, to the extent that symptomatic constructs define the patient’s self-identity we may foresee difficulties for change in therapy. On the other hand, it may be observed that all the positive construct poles are located together, close to the ideal self and far from the self now (which could be expressed like this: “If only I was fighter and respectful with family… everything would change”). For James, the change in one construct implies a change in many others, which renders the objective of change too large and difficult to achieve, as it becomes overly idealized and magnified.

Another feature of James’s grid is the low differentiation and high polarization of his construct system. Actually, cognitive rigidity has been associated with delusions[25,26] and with severity of the course of depression[27-29]. Polarization could be considered as a measure of cognitive rigidity as it reflects dichotomous thinking, the “all-or-nothing” style[17]. Also, the high PVAFF of James’s grid indicates a tendency to one-dimensional thinking. Therefore, reducing the tendency to making extreme judgments and increasing his cognitive differentiation would be reasonable targets for his therapeutic process, which is one of the lines of the MCT + work, introducing doubt into reasoning[30].

Another issue of the case conceptualization of James is the perceived relationship of his parents and his main persecutory figure. Constructs related to malevolence and hostile content have been associated with the perceived main persecutors in paranoid psychotic patients in a repertory grid study[31]. Within the constructs employed by James, those with a hostile intent reflect both his paranoid thoughts (about his ex-girlfriend) and the bad atmosphere experienced at home. These constructs employed by James might be related with the tradition of Expressed Emotion, conceptualized for the first time by Brown et al[32]. We do not have any direct assessment of James’s parents but his perception of them is based on hostility and criticism, which has been related with higher severity of positive symptoms[33] and risk for relapse in early psychosis populations[34]. Many studies have demonstrated the efficacy and importance of working with families with high expressed emotion in psychosis[35], so this would be another therapy focus.

We may also focus on the perceived similarity within the hostility constructs for the parents and the persecutory figure. Is there any possible explanation for this phenomenon? From a constructivist perspective, Gara[36] developed a set-theory model of person perception. Following this model, there are some main people in an individual’s life, called “supersets”, who provide the perceptual categories for the construing of other people, so the personality characteristics attributed to them would probably be first observed in these supersets. Usually supersets are found to be significant people in the subject’s life, very often his or her parental figures. Following this line of thought, it would be possible to consider as a clinical hypotheses that James’s supersets would be his mother and his father, and that he might be construing his persecutory figure in line with them in terms of hostility constructs, probably developed within the context of many years of conflict at home. This hypothesis reinforces the previous suggestion of including a family intervention in James’s therapeutic process. The intervention would focus on increasing the understanding of James disorder for the parents and on easing their supposedly conflictive family interactions. According to this clinical hypothesis, these improvements should facilitate changes in the tendency of James to perceive others in terms of threat and hostility, thereby also changing the structure of these core constructs for his identity and becoming less central. Thus, the intervention would also be expected to have a positive effect on his positive symptoms.

In conclusion, the use of the RGT in exploring the case of James has made it possible to understand how he construes his personal world at such a delicate moment, when his persecutory delusions are so severe. Furthermore, some possible key clinical hypotheses have been constructed with this information, signaling important areas such as self-concept and family relationships, as possible targets for therapy. However, the measures and clinical hypotheses derived from the repertory grid analysis must not be the only ones to consider in the implementation of therapy. RGT furnishes detailed information about the self and personal identity of patients, which is only one factor to consider in case formulation and therapy planning. The RGT is an assessment technique that provides the clinician with relevant systematic information about the personal meanings, self-concept, and cognitive structure of patients, which can also be applied to psychotic patients. This instrument has already demonstrated its utility in case formulation and research in psychology and psychotherapy[37,38], but its clinical and research potential for psychotic disorders has not been sufficiently exploited to date.

A 25-year-old man with severe persecutory delusions and hallucinations with threatening content without improvement following antipsychotic medication.

Psychiatric diagnosis of schizophrenia and personality disorder not otherwise specified. The onset of the disorder was 2 years ago.

Olanzapine 20 mg/d and Aripiprazole 400 mg/mo as depo. The case is going to start metacognitive individual training for psychosis.

The authors highlight the possibilities of the repertory grid technique to understand the personal meanings behind the symptoms and to identify targets for psychotherapy.

The article is very good as of its scientific.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Hosak L, Kravos M S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Coid JW, Ullrich S, Kallis C, Keers R, Barker D, Cowden F, Stamps R. The relationship between delusions and violence: findings from the East London first episode psychosis study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:465-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Freeman D, Garety P. Advances in understanding and treating persecutory delusions: a review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:1179-1189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kane JM. Treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57 Suppl 9:35-40. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Leucht S, Arbter D, Engel RR, Kissling W, Davis JM. How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:429-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Burns AM, Erickson DH, Brenner CA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for medication-resistant psychosis: a meta-analytic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:874-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Morrison AP, Turkington D, Pyle M, Spencer H, Brabban A, Dunn G, Christodoulides T, Dudley R, Chapman N, Callcott P. Cognitive therapy for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders not taking antipsychotic drugs: a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1395-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chadwick P. Person-based cognitive therapy for distressing psychosis. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons 2006; . |

| 8. | Kelly GA. The psychology of personal constructs. New York: Norton; . |

| 9. | Feixas G, Villegas M. Constructivismo y psicoterapia. Bilbao: Desclèe de Brouwer 2000; . |

| 10. | Winter D, Procter H. Formulation in personal and relational construct psychology: seeing the world through clients’ eyes. Formulation in Psychology and Psychotherapy: Making Sense of People’s Problems. New York: Routledge 2014; 145-172. |

| 11. | Feixas G, de la Fuente M, Soldevilla JM. La técnica de Rejilla como instrumento de evaluación y formulación de hipótesis clínicas. Spanish Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;153-171. |

| 12. | Winter D. Personal construct psychology in clinical practice: Theory, research and applications. London: Routledge 1992; . |

| 13. | Moritz S, Bohn Vitzthum F, Veckenstedt R, Leighton L, Woodward TS, Hauschildt M, Planells K. Programa Terapéutico de Entrenamiento Metacognitivo Individualizado para Psicosis (EMC+). Hamburg: VanHam Campus Press 2013; . |

| 14. | Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. Psychometric properties of the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1994;53:31-40. [PubMed] |

| 15. | González JC, Sanjuán J, Cañete C, Echanove MJ, Leal C. La evaluación de las alucinaciones auditivas: la escala PSYRATS. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2003;31:10-17. |

| 16. | Sanz J, Perdigón AL, Vázquez C. Adaptación española del Inventario para de Depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II): propiedades psicométricas en población general. Clínica y Salud. 2003;14:249-280. |

| 17. | Feixas G, Cornejo JM. Gridcor: Correspondence analysis for grid data. 2012;. |

| 18. | Bannister D. Conceptual structure in thought-disordered schizophrenics. J Ment Sci. 1960;106:1230-1249. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Barrowclough C, Tarrier N, Humphreys L, Ward J, Gregg L, Andrews B. Self-esteem in schizophrenia: relationships between self-evaluation, family attitudes, and symptomatology. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:92-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Romm KL, Rossberg JI, Hansen CF, Haug E, Andreassen OA, Melle I. Self-esteem is associated with premorbid adjustment and positive psychotic symptoms in early psychosis. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kesting ML, Lincoln TM. The relevance of self-esteem and self-schemas to persecutory delusions: a systematic review. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54:766-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sündermann O, Onwumere J, Kane F, Morgan C, Kuipers E. Social networks and support in first-episode psychosis: exploring the role of loneliness and anxiety. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:359-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Birchwood M, Iqbal Z, Chadwick P, Trower P. Cognitive approach to depression and suicidal thinking in psychosis. 1. Ontogeny of post-psychotic depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:516-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vorontsova N, Garety P, Freeman D. Cognitive factors maintaining persecutory delusions in psychosis: the contribution of depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:1121-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fowler D, Garety PA, Kuipers L. Cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis: Theory and practice. Chichester: Wiley, 2006. . |

| 26. | Garety PA, Freeman D, Jolley S, Dunn G, Bebbington PE, Fowler DG, Kuipers E, Dudley R. Reasoning, emotions, and delusional conviction in psychosis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:373-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Beevers CG, Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Miller IW. Cognitive predictors of symptom return following depression treatment. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:488-496. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Stange JP, Sylvia LG, da Silva Magalhães PV, Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Berk M, Nierenberg AA, Deckersbach T. Extreme attributions predict the course of bipolar depression: results from the STEP-BD randomized controlled trial of psychosocial treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:249-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Teasdale JD, Scott J, Moore RG, Hayhurst H, Pope M, Paykel ES. How does cognitive therapy prevent relapse in residual depression? Evidence from a controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:347-357. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Moritz S, Andreou C, Schneider BC, Wittekind CE, Menon M, Balzan RP, Woodward TS. Sowing the seeds of doubt: a narrative review on metacognitive training in schizophrenia. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34:358-66. |

| 31. | Paget A, Ellett L. Relationships among self, others, and persecutors in individuals with persecutory delusions: a repertory grid analysis. Behav Ther. 2014;45:273-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Brown GW, Rutter M. The measurement of family activities and relationships: a methodological study. Human Relations. 1966;19:241-263. |

| 33. | Cechnicki A, Bielańska A, Hanuszkiewicz I, Daren A. The predictive validity of expressed emotions (EE) in schizophrenia. A 20-year prospective study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:208-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Alvarez-Jimenez M, Priede A, Hetrick SE, Bendall S, Killackey E, Parker AG, McGorry PD, Gleeson JF. Risk factors for relapse following treatment for first episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Schizophr Res. 2012;139:116-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Pitschel-Walz G, Leucht S, Bäuml J, Kissling W, Engel RR. The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalization in schizophrenia--a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27:73-92. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Gara MA. A Set-Theoretical Model of Person Perception. Multivariate Behav Res. 1990;25:275-293. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Feixas G, Montesano A, Compañ V, Salla M, Dada G, Pucurull O, Trujillo A, Paz C, Muñoz D, Gasol M. Cognitive conflicts in major depression: between desired change and personal coherence. Br J Clin Psychol. 2014;53:369-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Winter DA. Repertory grid technique as a psychotherapy research measure. Psychother Res. 2003;13:25-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |