Published online Mar 22, 2015. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.138

Peer-review started: July 27, 2014

First decision: August 14, 2014

Revised: September 7, 2014

Accepted: November 17, 2014

Article in press: November 19, 2014

Published online: March 22, 2015

Processing time: 239 Days and 8.3 Hours

AIM: To compare adherence, response, and remission with light treatment in African-American and Caucasian patients with Seasonal Affective Disorder.

METHODS: Seventy-eight study participants, age range 18-64 (51 African-Americans and 27 Caucasians) recruited from the Greater Baltimore Metropolitan area, with diagnoses of recurrent mood disorder with seasonal pattern, and confirmed by a Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV, were enrolled in an open label study of daily bright light treatment. The trial lasted 6 wk with flexible dosing of light starting with 10000 lux bright light for 60 min daily in the morning. At the end of six weeks there were 65 completers. Three patients had Bipolar II disorder and the remainder had Major depressive disorder. Outcome measures were remission (score ≤ 8) and response (50% reduction) in symptoms on the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (SIGH-SAD) as well as symptomatic improvement on SIGH-SAD and Beck Depression Inventory-II. Adherence was measured using participant daily log. Participant groups were compared using t-tests, chi square, linear and logistic regressions.

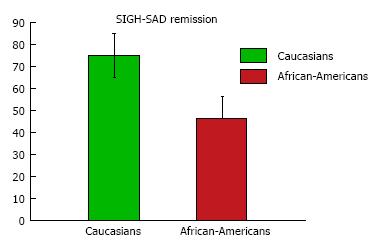

RESULTS: The study did not find any significant group difference between African-Americans and their Caucasian counterparts in adherence with light treatment as well as in symptomatic improvement. While symptomatic improvement and rate of treatment response were not different between the two groups, African-Americans, after adjustment for age, gender and adherence, achieved a significantly lower remission rate (African-Americans 46.3%; Caucasians 75%; P = 0.02).

CONCLUSION: This is the first study of light treatment in African-Americans, continuing our previous work reporting a similar frequency but a lower awareness of SAD and its treatment in African-Americans. Similar rates of adherence, symptomatic improvement and treatment response suggest that light treatment is a feasible, acceptable, and beneficial treatment for SAD in African-American patients. These results should lead to intensifying education initiatives to increase awareness of SAD and its treatment in African-American communities to increased SAD treatment engagement. In African-American vs Caucasian SAD patients a remission gap was identified, as reported before with antidepressant medications for non-seasonal depression, demanding sustained efforts to investigate and then address its causes.

Core tip: Consistent findings suggesting that light treatment is safe and effective for Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) emerged from prior research on samples with highly predominant Caucasian representation. As there are no previous reports on light treatment for SAD in African-Americans, we undertook the first study comparing effects of light treatment in African-American and Caucasian patients with Seasonal Affective Disorder. After six weeks of treatment, improvement in depression scores, response (50% improvement in symptoms), and adherence to treatment were similar between the two racial groups. However, the remission rates were significantly lower in African-Americans. Thus additional research is needed to better understand and ultimately reduce the remission gap between Caucasian and African-American patients with SAD.

-

Citation: Uzoma HN, Reeves GM, Langenberg P, Khabazghazvini B, Balis TG, Johnson MA, Sleemi A, Scrandis DA, Zimmerman SA, Vaswani D, Nijjar GV, Cabassa J, Lapidus M, Rohan KJ, Postolache TT. Light treatment for seasonal Winter depression in African-American

vs Caucasian outpatients. World J Psychiatr 2015; 5(1): 138-146 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v5/i1/138.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.138

Many species manifest behavioral and physiological changes in response to seasonal changes in daylength. Today, the effect of changes in daylength on humans may be smaller than in other animals because artificial lighting may blunt macro-environmental photoperiodicity. However, a sizable proportion of individuals manifest more pronounced seasonal changes, with some having major depression episodes in the fall and winter with spontaneous remission in spring and summer, defined as Seasonal Affective Disorder with winter pattern (SAD)[1]. Symptoms of SAD resemble seasonal changes in physiology and behavior in other photoperiodic mammals (including changes in appetite, weight, sleeping patterns, and patterns of social interactions). Light treatment is a safe and efficacious antidepressant intervention for SAD[1-4]. It may also prove to be a beneficial treatment for non-seasonal depression[4,5], as the mechanisms underlying the antidepressant action of bright light treatment overlap in part with those of antidepressant medications[6,7]. Although it appears that the prevalence of SAD in African-Americans is similar to the general population living at the same latitude[8], no previous study has focused on light treatment in African-Americans. Based on previously reported lower rates of adherence to antidepressants in African-American patients with non-seasonal depression[9,10], we hypothesized a lower adherence to light treatment, and a lower treatment response and remission in African-American patients when compared to Caucasian patients with SAD with winter pattern.

This was a six-week study primarily focused on prediction of remission and response following light treatment in African-American and Caucasian patients with Seasonal Affective disorder with Winter pattern. This study was an exploratory aim of an National Institute of Health-supported study (1R34MH073797-01A2). Recruitment took place over three consecutive Fall to Winter intervals, beginning in Fall 2007 and ending in Winter 2010. Approval for the study protocol was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland.

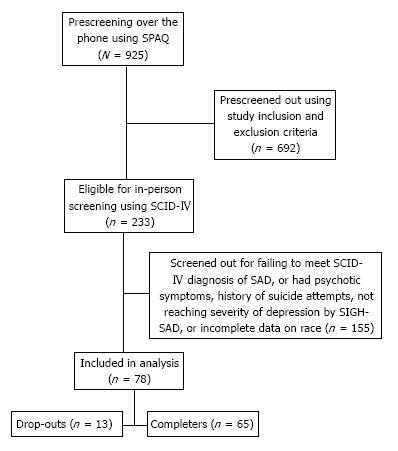

Participants in this study were patients with SAD with Winter pattern, recruited from the larger Baltimore metropolitan area through posters, flyers, and local newspaper ads. Figure 1 is a flow chart showing numbers of participants involved in the study from the initial telephone screening to the end. Patients self-identified as African-Americans or Caucasians consistent with the methodology recommended by the National Research Council consensus document on race and ethnicity[11].

Prescreening (screen #1) was conducted by phone using the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (SPAQ)[12]. This seventeen item psychometric instrument first designed by Rosenthal et al[12] has been widely used as a research instrument in the study of SAD. It has been shown to be an accurate screening instrument for identifying patients with SAD[13,14]. In one study by Magnusson, the SPAQ was shown to have sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value for that group of 94%, 73% and 45%, respectively[15]. In another study, Young et al[16] reported that the SPAQ has good psychometric properties in terms of score distribution, test-retest reliability, internal consistency, factor structure and item-latent traits relationships. Several other studies have shown high sensitivity but low specificity for the SPAQ, thus making it a good screening but poor diagnostic tool. In our study, participants who received a SPAQ global seasonality score of 11 or greater, reported a Winter pattern, as well as reported being at least moderately affected in daily functioning were considered positive screen. These individuals were invited to attend an in-person screening, informed consent session and for evaluation of eligibility to participate in the study.

In-person screening (screen #2) was performed by trained clinicians completing the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV Axis I Disorders-Clinician Version (SCID-Clinician Version)[17].

Inclusion criteria for the study were: age 18-64; history of Major Depressive Disorder or Bipolar II Disorder with seasonal pattern specifier, by DSM-IV, text revision and/or a score of 21 or greater on the Structured Interview Guide for Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression-SAD Version (SIGH-SAD)[18]. Eligible participants repeated the SIGH-SAD by phone interview 24 h prior to the first scheduled light session (screen #3), as well as on the morning of the first light session (screen #4). The participants had to demonstrate a consistent SIGH-SAD score of 21 or greater over 2 wk to be eligible for participation. Women of childbearing potential who were pregnant, nursing, or intending to become pregnant were excluded. Patients were also excluded if they used drugs or had history of alcohol abuse in the past year, if they met SCID criteria for Bipolar I, Psychotic disorders, if they reported past suicide attempts or active current suicidal ideation; or if they worked night shift. Other exclusion criteria were human immunodeficiency virus infection, systemic lupus, myocardial infarction or stroke, advanced glaucoma, and self-report of sensitivity to bright light or vision problems that are uncorrectable by glasses (e.g., if they answered negatively when queried as to whether they could distinguish colors or see stars at night). Treatment with antidepressants, mood stabilizers, or antipsychotic medications during the one month prior to screening, were also criteria for exclusion. After complete description of the study, participants’ understanding was evaluated using a research consent form booklet. Informed consent was obtained to show participants’ agreement and voluntary enrolment in the study.

Treatment was performed using the Apollo BriteLITE 6 (Apollo, American fork, Utah) whose name has since changed to Phillips BriteLITE 6. (Phillips HealthCare, Andover MA, product HF 3310 http://www.usa.philips.com/c-p/HF3310_60/britelite-6-energy-light with dimensions of 7.1 cm × 11 cm × 17.4 cm in/18 cm × 28 cm × 44 cm), and a peak wavelength of 545 nm.

The first light treatment session was conducted at the General Clinical Research Center of the University of Maryland, and included teaching and reviewing the light treatment procedures with participants and assessing response to the initial treatment. The intensity of 10000 lux was verified during the first session with a light meter and was obtained consistently from a distance of 33 cm from the center of the light box to the eyes. To maintain the correct distance from the light box to the eye level, a string measuring 34 cm was tied just above the light box. Participants were instructed to check their distance by straightening the string from the light box to a midpoint between their eyes, just above the nose.

Participants completed home-based daily bright light therapy for 6 wk, and treatment beginning at 10000 lux for 60 min upon awakening[19].

Previous studies have shown that light therapy is generally most effective when administered earlier in the day[19-21], as early morning treatment advances circadian rhythms, which are often phase delayed in SAD patients[20,21]. Participants were also instructed to use a timer on the light box to automatically shut off treatment after the recommended time interval.

The protocol allowed for flexible duration of light exposure with weekly adjustment. Weekly assessments were completed by phone with trained clinicians to assess mood symptoms, adherence to light, side effects, and measures related to hunger and food craving. We decided against a fixed-dose treatment instead preferring a flexible administration to maximize response and adherence in a clinically plausible context. Duration of light treatment was increased by fifteen minutes daily for participants who did not have at least a 30% reduction in SIGH-SAD score at the end of week one, a 50% reduction in SIGH-SAD score at the end of week two, or did not fulfill remission criteria (SIGH-SAD score ≤ 8) at the end of week three. Conversely, duration of treatment was decreased by fifteen minutes daily for any report of a side effect of 4 or greater on a 7-point Likert scale. The management of patients who showed poor response or side effects was discussed by a junior clinician with a senior psychiatrist with extensive experience with SAD and light treatment. The methodology used in our study was similar to a protocol used in recent clinical trials comparing light treatment to cognitive-behavioral therapy in patients with SAD[22].

Depression scores were assessed using two measures, one semi-structured interview, the SIGH-SAD[18], and a self report measure, the Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II)[23]. The primary outcome measure was the SIGH-SAD remission and response status, as defined above.

Participants were asked to complete a daily log reporting on the time and duration of light treatment used that day. Adherence logs were collected weekly by members of the research team and recorded. Adherence was defined as number of days in which light treatment was used as prescribed, and non-adherence defined as total number of days missed or not used as prescribed.

Descriptive measures include means and standard deviations for continuous variables and proportions and percents for categorical variables. Comparisons of the participants by race were made using t-tests for continuous variables (change from baseline for mood measures and adherence), and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to compare race sub-groups on changes in depression scores with adjustment for adherence, age, education, and gender. A sensitivity analysis for remission was performed including all participants who entered the study rather than just those who completed it. Four participants who did not receive treatment were also included. Assumptions for the sensitivity analysis were that: (1) If SIGH-SAD was ≤ 8 (i.e., remission) at week 6, then patient was considered in remission at the end of the study; (2) If SIGH-SAD data were missing at week 6, but the rating at week 4 was ≤ 8, then patient was considered in remission at the end of the study; and (3) If data for both weeks 4 and 6 were missing, then patients were considered not in remission. For the sensitivity analysis of adherence, all patients were included. If data for one week were missing, we counted that as 7 d missed.

No differences were found between African-Americans and Caucasians in mean age, gender, marital status, or proportion of bipolar II patients. The overall educational level was lower in African-Americans than Caucasians; specifically, a higher percentage of African-Americans had a high school education or less (52% African-Americans vs 26% Caucasians, P = 0.03) as shown in Table 1. There were no differences in frequency of side effects or adverse reactions between the two groups, and none were rated severe.

| Variable | African-Americans (n = 51) | Caucasians (n = 27) | P-value1 |

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 43.1 (10.3) | 47.0 (10.1) | 0.11 |

| Gender male | 19 (37.3) | 14 (51.9) | 0.21 |

| Bipolar II diagnosis | 2 (3.9) | 1 (3.7) | 0.96 |

| Education: High school or less | 26 (52.0) | 7 (25.9) | 0.03 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married or cohabiting | 7 (14.0) | 5 (18.5) | 0.42 |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 12 (24.0) | 11 (40.8) | 0.19 |

| Never married | 31 (62.0) | 11 (40.7) | 0.15 |

In Table 2 we present a comparison between the two racial groups on pre-treatment and post-treatment depression scores using SIGH-SAD and BDI-II. There was no statistical difference between average baseline and post-treatment depression scores between Caucasian and African-American patients.

| Variable | African-Americans | Caucasians | P-value1 |

| Pre-treatment mood scores | (n = 51) | (n = 27) | |

| SIGH-SAD, mean ± SD | 33 (6.9) | 31 (6.4) | 0.22 |

| BDI-II, mean ± SD | 25 (10.9) | 23.6 (8.4) | 0.58 |

| Post-treatment mood scores | (n = 41) | (n = 24) | |

| SIGH-SAD, mean ± SD | 9.31 (6.9) | 6.79 (6.0) | 0.15 |

| BDI-II, mean ± SD | 9 (7.9) | 7.3 (7.4) | 0.41 |

Table 3 presents main outcome measures following 6 wk of light treatment. Although both race groups showed similar decreases in the SIGH-SAD and BDI-II scores and similar post-treatment response rates, the proportion of remissions at post-treatment was significantly higher in Caucasians than in African-Americans (46% African-Americans vs 75% Caucasians, P = 0.02) (Figure 2). In a logistic regression model of remission at 6 wk adjusted for age, gender, education, and percent adherence, African-Americans were less likely to achieve remission than Caucasians (OR = 0.25; 95%CI: 0.08-0.81; P = 0.02). Table 3 also shows no group differences on adherence expressed as number of days missed or percent days adherence (equivalent measures). Adherence was 73% for African-Americans and 82% for Caucasians.

| Variable | African-Americans (n = 41) | Caucasians (n = 24) | P-value1 |

| Response, 50% reduction SIGH-SAD, n (%) | 33 (80.5) | 20 (83.3) | 0.78 |

| Remission, SIGH-SAD < 8, n (%) | 19 (46.3) | 18 (75.0) | 0.02 |

| SIGH-SAD, % change, mean ± SD | -70.4 (22.7) | 76.0 (22.6) | 0.34 |

| BDI-II, % change, mean ± SD | -61.8 (32.2) | -68.1 (32.9) | 0.46 |

| POMS-A, % change, mean ± SD | -46.6 (46.7) | -46.8 (48.8) | 0.98 |

| POMS-D, % change, mean ± SD | -52.7 (47.1) | -49.2 (54.9) | 0.78 |

| Treatment days missed, mean ± SD | 8.7 (11.0) | 7.4 (8.3) | 0.61 |

| Percent adherence, mean ± SD | 79.4 (26.2) | 82.4 (19.7) | 0.61 |

After linear regression adjustment for age, gender, education, and adherence, there were no significant differences in treatment related changes in depression scores between African-Americans and Caucasians. This is shown in Table 4.

| Variable | African-Americans (n = 41) | Caucasians (n=24) | P-value1 |

| Mood scale | |||

| SIGH-SAD | -22.9 (1.6) | -25.2 (2.1) | 0.41 |

| BDI-II | -16.6 (2.0) | -16.4 (2.6) | 0.95 |

Table 5 presents results of the intent-to-treat sample, including all those who were randomized. Based on the assumptions described in the Methods (see sensitivity analysis) for n = 78, in the logistic regression model of remission at 6 wk (adjusted for gender, percent adherence, and education) African-Americans were less likely to achieve remission than Caucasians (OR = 0.21, 95%CI: 0.07-0.66; P = 0.008). Those who were lost to follow up at 6 wk were compared with those with 6 wk data using χ2 and t-test analyses. No significant race group differences were found for gender (P = 0.36), age (P = 0.96), baseline SIGH-SAD (P = 0.68), and baseline BDI-II (P = 0.71). An ANCOVA model including race, gender, and age did not show significant difference between the groups in light exposure duration (F = 2.480; df = 1, 60; P = 0.12).

In this study, African-American participants with SAD had a lower remission rate than Caucasian participants following six weeks of light treatment, but there were no significant differences between the two race groups in adherence, average symptomatic improvement, and response rates. To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating differences between African-Americans and Caucasians in response to light treatment in SAD.

Racial differences for treatment response and remission have been previously reported with pharmacological treatment of non-seasonal depression. From the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, Lesser et al[24] reported that African-Americans had lower remission rates on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression and the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report (18.6% and 22% respectively) compared to whites (30.1% and 36.1%). However, there was no statistically significant difference between races after adjusting for baseline socioeconomic, clinical, and demographic differences. In their analysis of DNA samples from the STAR*D trial, Binder et al. showed that a Single Nucleotide Polymorphism [single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP); rs 10473984] variation within the corticotrophin-releasing hormone binding protein locus appeared contributory to poor response and lower remission to treatment with citalopram in African-Americans and Hispanic patients[25]. In an earlier report from the STAR*D trial, McMahon et al[26] reported that the A allele of the SNP marker HTR2A which encodes for serotonin 2A receptor was over six times more frequent in white than in black participants and was responsible for better response to citalopram by white participants compared to blacks. Among many factors that may explain why certain outcomes such as adherence and response rates were similar in African-Americans and Caucasians in our study in contrast to significant racial differences reported in previous pharmacological trials, African-Americans may perceive light therapy as more acceptable and less stigmatizing than medications. This hypothesis was not formally tested.

In general, the response rate of 81% and remission rate of 52% reported in this study are somewhat more favorable compared to other studies on light treatment for SAD[3,20,21,27]. For instance, Lam et al[28] compared light treatment using 10000 lux bright light for 30 min daily with fluoxetine 20 mg orally daily for 8 wk. Their study showed no significant difference in clinical response rate, which was 67% for both groups, while remission rates were 50% for light therapy and 54% for fluoxetine.

We also note that there was no significant difference in adherence to daily light treatment between African-Americans and their Caucasian counterparts in our study. The adherence of 73% in African-Americans and 82% in Caucasians in our study is similar to the 83.3% found by Michalak et al[29], and it compares favorably with adherence to antidepressants[30]. When compared to antidepressants, light treatment has more benign side effects[28], potentially leading to higher adherence. Other side effects, such as precipitating hypomania and mania, are similar in light treatment and antidepressants[31]. Additionally, more rapid improvement with light treatment[28,32] may contribute to a better adherence with this non-pharmacological treatment.

The previously reported higher melanin content of the pupil and retinal pigment epithelium in African-Americans[33,34] may reduce the retinal illuminance in African-American SAD patients during light treatment. However, the magnitude of this effect is unclear, as is the effect of these reduced levels on remission.

Limitations of this study include an open label design, a limited sample size, and absence of objective markers of adherence. The recruitment method may have induced a selection bias that may have influenced favorably, but spuriously, the adherence rate.

We also did not collect information on number of lifetime depressive episodes or duration of current episode. The flexible dosing of treatment in our study, although representative of real world clinical practice, may have affected the outcomes. In addition, our generalizability may be limited as our inclusion and exclusion criteria may have led to selectively including a less severe subset of patients, having excluded patients with history of suicide attempts, current suicidal ideation, Bipolar 1 disorder, and comorbid substance abuse as well as patients on often used psychotropic medications. Including patients on psychotropic medications in the study, although increasing its generalizability, would have required unaffordably larger sample size and budget, to permit appropriate statistical adjustments.

This is the first study directly comparing light treatment outcome in two groups, African-American and Caucasian patients. A similar average degree of symptomatic improvement and adherence in African-Americans, combined with a previously reported lower awareness of SAD in this minority group[8] justify increasing psychoeducation outreach efforts regarding SAD and light treatment in that sub-sample of the population. However, there is a need to better understand the lower remission rate in African-Americans, similar to that of antidepressant medications. In the subset of patients who respond but do not achieve remission with light treatment, combination with antidepressant medication or cognitive behavioral therapy is currently advocated. Considering differences in pupil and retinal pigmentation in African-Americans it might be possible that specific protocols with distinct light intensity and wavelength could reduce the reported racial remission gap. This is particularly important, as complete remission with antidepressant treatment is the target for all treatment modalities for mood disorders, considering implications for health, functioning, and quality of life.

The authors thank Monika Acharya, MD, Muhammad Tariq, MD, Humaira Siddiqi, MD, and Partam Manalai, MD for their help in screening and rating patients. The authors declare no conflict of interest within the past 5 years.

The authors’ prior research has suggested that Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) prevalence in African-Americans is similar to that of the general population living at similar altitude, and awareness of the disorder and its treatment is low among African-Americans. This study is the first to investigate effects of light treatment, generally considered a first-line treatment for SAD, in African-Americans as compared to Caucasian patients.

Research in this area is moving towards identification of biological markers of prediction of response to light therapy, as well as combination of treatments and individualizing modalities and sequences of treatment.

Multiple areas of investigation have included investigating ways of administering light treatment (e.g., dawn simulators), wavelength of treatment (lower wavelength stimulating novel photoreceptors-e.g., melanopsin receptors in the retinal ganglion cells) and the use of psychotherapy and combination treatments to prevent future episodes of SAD rather than just treating the current episode. African-American patients may require either a modified protocol of light treatment or an early combination of different treatment modalities.

SAD could be quite disabling. Light treatment is safe and effective for SAD and appears attractive especially to patients concerned about the side effects of antidepressant medications, or who do not have time for psychotherapy. Furthermore, for patients who require combination with antidepressants, the dose of medication could be kept lower and thus minimize side effects at the end of Applications African-American SAD patients manifested a remission gap in comparison to Caucasian patients, and additional research will be needed to uncover what leads to it in order to design alternative treatment regiments to improve outcome.

SAD refers to depressive episodes occurring during certain seasons and remitting spontaneously with change of season. The most common pattern is depression in fall/winter that remits in spring/summer.

The methodology is adequate and the manuscript is well written.

P- Reviewer: Chakrabarti S, Tampi RR S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Rosenthal NE, Sack DA, Gillin JC, Lewy AJ, Goodwin FK, Davenport Y, Mueller PS, Newsome DA, Wehr TA. Seasonal affective disorder. A description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:72-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1612] [Cited by in RCA: 1407] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Terman JS, Terman M, Schlager D, Rafferty B, Rosofsky M, Link MJ, Gallin PF, Quitkin FM. Efficacy of brief, intense light exposure for treatment of winter depression. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1990;26:3-11. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Eastman CI, Young MA, Fogg LF, Liu L, Meaden PM. Bright light treatment of winter depression: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:883-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Golden RN, Gaynes BN, Ekstrom RD, Hamer RM, Jacobsen FM, Suppes T, Wisner KL, Nemeroff CB. The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders: a review and meta-analysis of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:656-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 526] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lieverse R, Van Someren EJ, Nielen MM, Uitdehaag BM, Smit JH, Hoogendijk WJ. Bright light treatment in elderly patients with nonseasonal major depressive disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:61-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Neumeister A, Turner EH, Matthews JR, Postolache TT, Barnett RL, Rauh M, Vetticad RG, Kasper S, Rosenthal NE. Effects of tryptophan depletion vs catecholamine depletion in patients with seasonal affective disorder in remission with light therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:524-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wirz-Justice A. From the basic neuroscience of circadian clock function to light therapy for depression: on the emergence of chronotherapeutics. J Affect Disord. 2009;116:159-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Agumadu CO, Yousufi SM, Malik IS, Nguyen MC, Jackson MA, Soleymani K, Thrower CM, Peterman MJ, Walters GW, Niemtzoff MJ. Seasonal variation in mood in African American college students in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1084-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Melfi CA, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, Robinson RL. Racial variation in antidepressant treatment in a Medicaid population. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:16-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bogner HR, Lin JY, Morales KH. Patterns of early adherence to the antidepressant citalopram among older primary care patients: the prospect study. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:103-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bulatao RA, Anderson NB. Understanding Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life: A Research Agenda. Washington: National Academies Press 2004; 9. |

| 12. | Rosenthal NE, Genhart MJ, Sack DA, Skwerer RJ, Wehr TA. Seasonal affective disorder and its relevance for the understanding and treatment of bulimia. The Psychobiology of Bulimia. Washington: American Psychiatric Press 1987; 205-228. |

| 13. | Magnusson A. An overview of epidemiological studies on seasonal affective disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:176-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mersch PP, Vastenburg NC, Meesters Y, Bouhuys AL, Beersma DG, van den Hoofdakker RH, den Boer JA. The reliability and validity of the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire: a comparison between patient groups. J Affect Disord. 2004;80:209-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Magnusson A. Validation of the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (SPAQ). J Affect Disord. 1996;40:121-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Young MA, Blodgett C, Reardon A. Measuring seasonality: psychometric properties of the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire and the Inventory for Seasonal Variation. Psychiatry Res. 2003;117:75-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-Clinician Version). New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute Biometrics Research Department 1997; . |

| 18. | Williams JBW, Link MJ, Rosenthal NE, Amira L, Terman M. Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Seasonal Affective Disorders Version (SIGH SAD), revised. New York: New York State Psychiatr Inst 2002; . |

| 19. | Levitan RD. What is the optimal implementation of bright light therapy for seasonal affective disorder (SAD)? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005;30:72. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Terman M, Terman JS, Quitkin FM, McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Rafferty B. Light therapy for seasonal affective disorder. A review of efficacy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1989;2:1-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Terman JS, Terman M, Lo ES, Cooper TB. Circadian time of morning light administration and therapeutic response in winter depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:69-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rohan KJ, Roecklein KA, Tierney Lindsey K, Johnson LG, Lippy RD, Lacy TJ, Barton FB. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy, light therapy, and their combination for seasonal affective disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:489-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67:588-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3738] [Cited by in RCA: 4053] [Article Influence: 139.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lesser IM, Castro DB, Gaynes BN, Gonzalez J, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, Trivedi M, Luther JF, Wisniewski SR. Ethnicity/race and outcome in the treatment of depression: results from STAR*D. Med Care. 2007;45:1043-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Binder EB, Owens MJ, Liu W, Deveau TC, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Fava M, Bradley B, Ressler KJ, Nemeroff CB. Association of polymorphisms in genes regulating the corticotropin-releasing factor system with antidepressant treatment response. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:369-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | McMahon FJ, Buervenich S, Charney D, Lipsky R, Rush AJ, Wilson AF, Sorant AJ, Papanicolaou GJ, Laje G, Fava M. Variation in the gene encoding the serotonin 2A receptor is associated with outcome of antidepressant treatment. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:804-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 382] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Terman M, Terman JS. Controlled trial of naturalistic dawn simulation and negative air ionization for seasonal affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2126-2133. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Lam RW, Levitt AJ, Levitan RD, Enns MW, Morehouse R, Michalak EE, Tam EM. The Can-SAD study: a randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of light therapy and fluoxetine in patients with winter seasonal affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:805-812. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Michalak EE, Murray G, Wilkinson C, Dowrick C, Lam RW. A pilot study of adherence with light treatment for seasonal affective disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:315-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lee MS, Lee HY, Kang SG, Yang J, Ahn H, Rhee M, Ko YH, Joe SH, Jung IK, Kim SH. Variables influencing antidepressant medication adherence for treating outpatients with depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:216-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sohn CH, Lam RW. Treatment of seasonal affective disorder: unipolar versus bipolar differences. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6:478-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Virk G, Reeves G, Rosenthal NE, Sher L, Postolache TT. Short exposure to light treatment improves depression scores in patients with seasonal affective disorder: A brief report. Int J Disabil Hum Dev. 2009;8:283-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | van den Berg TJ, IJspeert JK, de Waard PW. Dependence of intraocular straylight on pigmentation and light transmission through the ocular wall. Vision Res. 1991;31:1361-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kardon RH, Hong S, Kawasaki A. Entrance pupil size predicts retinal illumination in darkly pigmented eyes, but not lightly pigmented eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:5559-5567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |