Published online Sep 22, 2014. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v4.i3.56

Revised: July 16, 2014

Accepted: August 27, 2014

Published online: September 22, 2014

Processing time: 157 Days and 1.2 Hours

AIM: To explore the way in which Latin American psychiatrists approach the screening of vascular risk factors in patients receiving antipsychotic medication.

METHODS: This was a descriptive, cross sectional study that surveyed Latin-American physicians to evaluate differences between groups divided in three main sections. The first section included demographic and professional data. The second section asked about the available medical resources: weighing scales, sphygmomanometer and measuring tape. Finally, the third section aimed at looking into the attitudes towards cardiovascular prevention. The latter was also divided into two subsections. In the first one, the questions were about weight, blood pressure and waist perimeter. In the second subsection the questions asked about the proportion of patients: (1) that suffered from overweight and/or obesity; (2) whose lipids and glycemia were controlled by the physician; (3) that were questioned by, and received information from the physician about smoking; and (4) that received recommendations from the physician to engage in regular physical activity. The participants were physicians, users of the medical website Intramed. The visitors were recruited by a banner that invited them to voluntarily access an online self-reported structured questionnaire with multiple options.

RESULTS: We surveyed 1185 general physicians and 792 psychiatrists. Regarding basic medical resources, a significantly higher proportion of general physicians claimed to have weighing scales (χ2 = 404.9; P < 0.001), sphygmomanometers (χ2 = 419.3; P < 0.001), and measuring tapes (χ2 = 336.5; P < 0.001). While general physicians measured overweight and metabolic indexes in the general population in a higher proportion than in patients treated with antipsychotics (Z = -11.91; P < 0.001), psychiatrists claimed to measure them in patients medicated with antipsychotics in a higher proportion than in the general population (Z = -3.26; P < 0.001). Also general physicians tended to evaluate smoking habits in the general population more than psychiatrists (Z = -7.02; P < 0.001), but psychiatrists evaluated smoking habits in patients medicated with antipsychotics more than general physicians did (Z = -2.25; P = 0.024). General physicians showed a significantly higher tendency to control blood pressure (χ2 = 334.987; P < 0.001), weight (χ2 = 435.636; P < 0.001) and waist perimeter (χ2 = 96.52; P < 0.001) themselves and they did so in all patients. General physicians suggested physical activity to all patients more frequently (Z = -2.23; P = 0.026), but psychiatrists recommended physical activity to patients medicated with antipsychotics more frequently (Z = -7.53; P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: Psychiatrists usually check vascular risk factors in their patients, especially in those taking antipsychotics. General practitioners check them routinely without paying special attention to this population.

Core tip: This is a descriptive, cross sectional study that surveyed Latin-American physicians to explore the way in which Latin-American psychiatrists approach the screening of vascular risk factors in patients receiving antipsychotic medication. We surveyed 1185 general physicians and 792 psychiatrists. We found that psychiatrists usually check vascular risk factors in their patients, especially those taking antipsychotics. General practitioners check them routinely without paying special attention to this population.

- Citation: Richly P, López P, Gleichgerrcht E, Flichtentrei D, Prats M, Mastandueno R, Bustin J, Cetkovich-Bakmas M. Psychiatrists’ approach to vascular risk assessment in Latin America. World J Psychiatr 2014; 4(3): 56-61

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v4/i3/56.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v4.i3.56

Heart attack and stroke are the two leading causes of disability and mortality worldwide[1]. Tackling vascular risk factors such as high blood pressure, cholesterol, overweight/obesity, tobacco use, lack of physical activity, and hyperglycemia, among others, is the most efficient strategy to prevent vascular disease[2]. In fact, the presence of at least two of these risk factors is associated with the well-established metabolic syndrome, a disorder characterized by a constellation of risks that appear to have a common physiopathology leading to markedly increased cardiovascular risk[3]. Because these factors can be controlled, treated or modified, their early detection is crucial among younger patients, thus enabling early intervention[4].

The combination of two or more of these risk factors can be considered metabolic syndrome due to the risk increase that the combination generates, together with the hypothesis that they share a common physiopathology[3].

The use of antipsychotics has been linked with the development of metabolic syndrome, especially in younger patients[5,6]. Frequently, patients diagnosed with schizophrenia are prescribed antipsychotic medication for long periods of time. They are a particularly vulnerable population because schizophrenia itself is linked to an increased burden of cardiovascular disease[7,8]. In fact, cardiovascular causes of death are about twice as common in patients suffering from schizophrenia as they are in the general population, with a peak relative risk in early life. Certain risk factors such as weight, smoking, diet and activity levels appear to have a critical role in this phenomenon[5]. However, physicians don’t usually take this into account, neither before prescribing antipsychotics nor during treatment[9].

This issue becomes a priority since detection of high risk population may lead to a more thorough evaluation and early treatment of the vascular disease[10]. Although most of the epidemiological data comes from European and North American populations, some studies have preliminarily shown that comparable trends occur in developing countries[11]. For this reason, understanding the way in which physicians approach the issue of screening for vascular risk factors in patients receiving antipsychotic medication is important in order to design better training strategies that will ultimately translate into more efficient patient care. The present study sought to explore this issue.

This study was descriptive, cross-sectional with a control group.

Potential participants were licensed physicians registered as psychiatrists or general physicians who were users of Intramed (http://www.intramed.net), an online portal for health professionals. Visitors were recruited by a banner that invited them to voluntarily access an online questionnaire. All participants gave their informed consent by clicking an “I agree” button placed beneath an explanatory letter. Potential respondents were informed of the anonymity of their responses, which was achieved by deleting their names and email addresses from the database.

The questionnaire was designed by researchers from INECO (Institute of Cognitive Neurology, Buenos Aires) together with researchers from Intramed. It consisted of a self-reported structured questionnaire with multiple options. It was divided into three main sections: demographic/professional profile, availability of basic medical resources, and attitudes towards cardiovascular prevention.

The first section gathered basic demographic and professional data. The second section asked about participants’ access to basic medical resources in their workplaces, namely: weighing scales, sphygmomanometer, and measuring tape. We picked these items in particular because of their relevance in obtaining objective measures directly associated with risk factors for metabolic syndrome.

The third section asked about participants’ attitudes towards cardiovascular prevention, and was divided into two subsections. In the first one, questions were about weight, blood pressure, and waist perimeter. We asked whether physicians measured these variables, the way in which they did it, and in which patients (i.e., all patients or those that received anti-psychotic medication). In the second subsection, we asked about the proportion of patients seen by participants in their daily practice: (1) that suffered from overweight and/or obesity; (2) whose lipid levels and glycemia were controlled by the physician; (3) that have been questioned by, and received information from the physician about smoking; and (4) that were recommended by the physician to engage in regular physical activity.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM-SPSS 19.0 package. When inferential hypotheses were tested on categorical data, Pearson χ2 tests were calculated in order to evaluate differences across groups. Comparisons between groups on ordinal measurements were conducted using independent Mann-Whitney U test. Due to the large sample size of the present study and the fact that, in this case, the value of U approaches a normal distribution, the null hypothesis has been tested by a Z-test to facilitate the comprehension of the analysis.

A total of 1977 Latin-American physicians completed the survey. The sample consisted of 1185 general practitioners (544 female and 641 male; age = 47.04) and 792 psychiatrists (440 female and 352 male, age = 48.92). There was a significant difference in the proportion of participants from each gender between both specialties (χ2 = 17.677, P < 0.001).

Regarding access to measurement instruments, a significantly higher proportion of general physicians claimed to have weighing scales (χ2 = 404.9; P < 0.001), sphygmomanometers (χ2 = 419.3; P < 0.001), and measuring tapes (χ2 = 336.5; P < 0.001) at their practice sites (Table 1).

| General physicians | Psychiatrists | P value | |||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Weighing scales | 1089 | 91.9 | 416 | 52.5 | < 0.001 |

| Sphygmomanometers | 1176 | 99.2 | 530 | 66.9 | < 0.001 |

| Measuring tapes | 820 | 69.2 | 215 | 27.1 | < 0.001 |

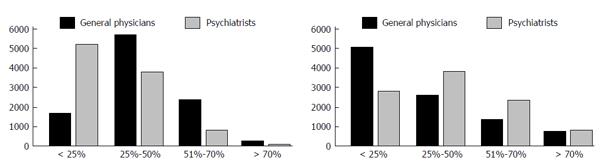

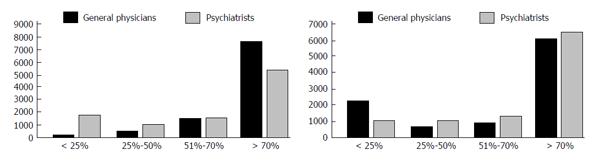

Regarding routine measurement of overweight and metabolic indexes, psychiatrists claimed to measure these variables in patients medicated with antipsychotics (AP) in a significantly higher proportion than in the general population (Z = -3.26; P < 0.001). On the other hand, general physicians answered that they measured overweight and metabolic indexes in the general population in a higher proportion than in patients treated with AP (Z = -11.91; P < 0.001) (Figures 1 and 2).

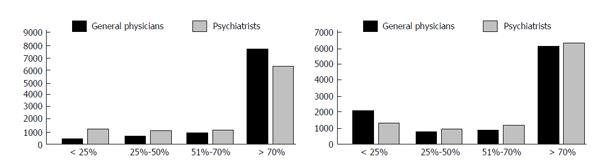

In regards to the assessment of tobacco use, general physicians tended to evaluate smoking habits in the general population more than psychiatrists (Z = -7.02; P < 0.001), but these evaluated smoking habits in patients medicated with AP more than general physicians did (Z = -2.25; P = 0.024) (Figure 3).

General physicians showed a significantly higher tendency to control blood pressure than psychiatrists (χ2 = 334.987; P < 0.001). They also tended to differ in how, and in which patients, they did this, because they primarily measured it themselves (χ2 = 641.785; P <.001) and they controlled it mostly in all patients (χ2 = 162.092; P < 0.001) (Table 2).

| General physicians | Psychiatrists | P | |||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Blood pressure | 1175 | 99.2 | 572 | 72.2 | < 0.001 |

| Weight | 1185 | 100.0 | 792 | 100.0 | NS |

| Waist perimeter | 478 | 40.3 | 153 | 19.3 | < 0.001 |

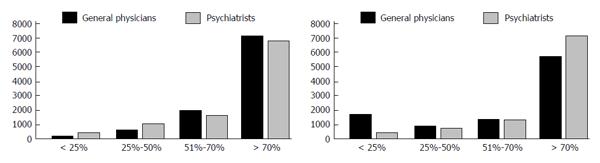

In addition to this, significant differences existed in regards to the recommendation by general physicians and psychiatrists as to physical activity. General physicians recommended physical activity to all patients more frequently (Z = -2.23; P = 0.026). On the other hand psychiatrists recommended physical activity to patients medicated with AP more frequently (Z = -7.53; P < 0.001) (Figure 4).

Even though all respondents claimed they controlled weight (Table 2), we found significant differences between the way in which it was controlled, and in which patients it was controlled. General physicians, in a higher proportion, controlled weight themselves (χ2 = 435.636; P < 0.001) and they did so in all patients (χ2 = 251.214; P < 0.001).

Additionally, a significant difference can be observed between general physicians and psychiatrists in the control of the patients’ waist perimeter (Table 2), in how it was done, and in which patients it was controlled. General physicians, in a higher proportion, controlled waist perimeter (χ2 = 96.52; P < 0.001) and they also, in a higher proportion, did so themselves (χ2 = 211.308; P < 0.001). They tended to control waist perimeter more frequently in all patients (χ2 = 119.17; P < 0.001).

As can be seen in the results, most psychiatrists are aware of the importance of taking into account vascular risk factors. Psychiatrists claim that they usually check them in their patients, especially in those taking antipsychotics. Despite controlling vascular risk factors in their patients, psychiatrists tend to refer them to general practitioners instead of handling this issue themselves.

As expected, general practitioners routinely check vascular risk factors in all their patients. However, they don’t pay special attention to patients taking antipsychotics, even though these medications increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease.

A limitation of this study is that data was gathered through a self-reported questionnaire which, as was previously suggested, has a tendency of overestimating performance of respondents[12]. Also, the use of an online questionnaire, instead of an interview, represents a limitation of the data quality.

Finally, even though doctors seem to be more aware of the importance of cardiovascular burden in psychiatric patients, there still is a lot of work to do in this regard, since epidemiological studies show the paucity of actual monitoring of vascular risk factors in patients taking antipsychotics[13]. Yet, not only screening of vascular risk factors in this population is lacking, but also treatment when detected[14].

A deeper integration of psychiatric and physical health care systems for patients with mental disorders is urgently needed.

Tackling risk factors is the most efficient strategy to prevent vascular disease. The use of antipsychotics has been linked to the development of metabolic syndrome, especially in younger patients.

Epidemiological data seems to show that psychiatrists usually neither screen vascular risk factors before prescribing antipsychotics nor during treatment.

Recent reports have highlighted that patients diagnosed with schizophrenia are prescribed antipsychotic medication for long periods of time, and as schizophrenia itself is associated with an increased burden of cardiovascular disease, the screening and the control of certain risk factors such as weight, smoking, diet and activity levels appear to be critical.

Understanding the way physicians approach the issue of screening for vascular risk factors in patients receiving antipsychotic medication is important in order to design better training strategies.

High blood pressure, cholesterol, overweight/obesity, tobacco use, lack of physical activity, and hyperglycemia are the most relevant modifiable vascular risk factors.

This is an original study involving a large amount of workload.

P- Reviewer: Ciccone MM, Dumitrascu DL S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095-2128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9500] [Cited by in RCA: 9582] [Article Influence: 737.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mendis S, Puska P, Norrving B. Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control. World Health Organization (in collaboration with the World Heart Federation and World Stroke Organization): Geneva 2011; . |

| 3. | Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SC. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8720] [Cited by in RCA: 10558] [Article Influence: 659.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Weintraub WS, Daniels SR, Burke LE, Franklin BA, Goff DC, Hayman LL, Lloyd-Jones D, Pandey DK, Sanchez EJ, Schram AP. Value of primordial and primary prevention for cardiovascular disease: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;124:967-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 424] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mitchell AJ, Malone D. Physical health and schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:432-437. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Pramyothin P, Khaodhiar L. Metabolic syndrome with the atypical antipsychotics. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010;17:460-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hennekens CH. Increasing global burden of cardiovascular disease in general populations and patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68 Suppl 4:4-7. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Ferreira L, Belo A, Abreu-Lima C. A case-control study of cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular risk among patients with schizophrenia in a country in the low cardiovascular risk region of Europe. Rev Port Cardiol. 2010;29:1481-1493. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Laundon W, Muzyk AJ, Gagliardi JP, Christopher EJ, Rothrock-Christian T, Jiang W. Prevalence of baseline lipid monitoring in patients prescribed second-generation antipsychotics during their index hospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:380-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ciccone MM, Bilianou E, Balbarini A, Gesualdo M, Ghiadoni L, Metra M, Palmiero P, Pedrinelli R, Salvetti M, Scicchitano P. Task force on: ‘Early markers of atherosclerosis: influence of age and sex’. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2013;14:757-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bou Khalil R. Atypical antipsychotic drugs, schizophrenia, and metabolic syndrome in non-Euro-American societies. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2012;35:141-147. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Baxter P, Norman G. Self-assessment or self deception? A lack of association between nursing students’ self-assessment and performance. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:2406-2413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mitchell AJ, Delaffon V, Vancampfort D, Correll CU, De Hert M. Guideline concordant monitoring of metabolic risk in people treated with antipsychotic medication: systematic review and meta-analysis of screening practices. Psychol Med. 2012;42:125-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Steylen PM, van der Heijden FM, Kok HD, Sijben NA, Verhoeven WM. Cardiometabolic comorbidity in antipsychotic treated patients: need for systematic evaluation and treatment. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17:125-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |