Published online Oct 22, 2012. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v2.i5.71

Revised: June 20, 2012

Accepted: September 26, 2012

Published online: October 22, 2012

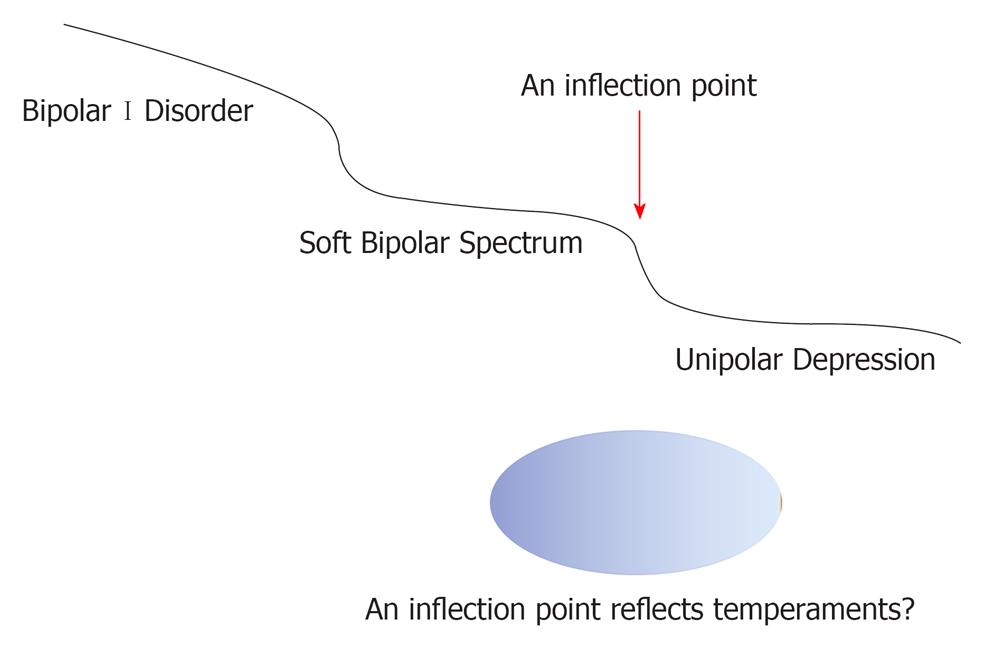

The bipolar spectrum is a concept which bridges bipolar I disorder and unipolar depression. As Kraepelin described, there may be continuity across mood disorders. If this is the case, why should we discriminate for drug choice For example, it is generally accepted that mood stabilizers should be used for the bipolar spectrum, whereas antidepressants are for unipolar depression. If these disorders are diagnostically continuous, it is possible that the same drug could be effective in treating both bipolar I disorder/spectrum and unipolar depression. To resolve this question, I would like to propose my hypothesis that there is an inflexion point which constitutes the boundary between the bipolar spectrum and unipolar depression. It is likely that this inflexion point consists of temperaments as, reportedly, there are many significant differences in the presence of various temperaments between the bipolar spectrum (bipolar II, II1/2 and IV) and unipolar depression. These findings suggest that temperaments could draw a boundary between the bipolar spectrum and unipolar depression. Moreover, it has been shown that certain temperaments may be associated with several biological factors and may be associated with drug response. As such, whilst the concept of the bipolar spectrum emphasizes continuity, it is the proposed inflexion point that discriminates drug responses between the bipolar spectrum and unipolar depression. At the moment, although hypothetical, I consider this idea worthy of further research.

- Citation: Terao T. Bipolar spectrum: Relevant psychological and biological factors. World J Psychiatr 2012; 2(5): 71-73

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v2/i5/71.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v2.i5.71

Manic depressive insanity (Manisch Depressives Irresein) was first denoted in the sixth edition of Kraepelin’s textbook (1899) as a further development of the concept of periodic psychoses (Periodisches Irresein, the fifth edition of Kraepelin’s textbook, 1896)[1]. Kraepelin described diverse depressive and manic states, depicted a transition from depression to mania or hypomania and vice versa during the course of the disorder and stressed the importance of the course of the disorder. Thereby, he endorsed what we today refer to as a dimensional concept in psychiatric classification and formulated what we now call a spectrum concept of mood disorders[1].

This spectrum concept of mood disorders is now referred to as the (soft) bipolar spectrum, which represents a partial return to Kraepelin’s broad concept of manic depressive illness. Although bipolar I and bipolar II are part of the official nomenclature of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), this concept of the bipolar spectrum is not represented in this manual. Akiskal et al[2,3] has energetically described several types of the bipolar spectrum, such as bipolar 1/2 (schizobipolar disorder), bipolar I1/2 (depression with protracted hypomania), bipolar II1/2 (depression superimposed on cyclothymic temperament), bipolar III (repeated depression plus hypomania occurring solely in association with antidepressant or other somatic treatment), bipolar III1/2 (repeated hypomania occurring in the context of substance and/or alcohol abuse), bipolar IV (depression superimposed on the hyperthymic temperament) and so on.

Kraepelin described four basic affective dispositions (depressive, manic, cyclothymic and irritable)[4]. Current research findings show that specific affective temperament types (depressive, cyclothymic, hyperthymic, irritable and anxious)[5,6] are subsyndromal (trait-related) manifestations and also commonly the antecedents of minor and major mood disorders. According to Akiskal et al[2], there are 2 subtypes of the bipolar spectrum which are not associated with manic or hypomanic states. These are bipolar II1/2 (depression in those who have the cyclothymic temperament) and bipolar IV (depression in those who have the hyperthymic temperament).

Goto et al[7] focused on depressive patients with the cyclothymic temperament (bipolar II1/2) and depressive patients with the hyperthymic temperament (bipolar IV), as well as bipolar II. Of 46 patients, the depressive temperament was present in 31 patients, the cyclothymic temperament in 33, the hyperthymic temperament in 14, the irritable temperament in 24, and the anxious temperament in 24. Although there was no significant difference for the presence of each temperament between patients with bipolar disorder and patients with major depression (according to DSM-IV-TR), there were many significant differences in temperaments between the bipolar spectrum (bipolar II, II1/2 and IV) and unipolar depression. These findings suggest that temperaments may draw a boundary between the bipolar spectrum and unipolar depression, as depicted in Figure 1.

According to Goto et al[7], of their 39 patients with the bipolar spectrum, patients on lithium treatment had significantly higher remission rates than patients without lithium treatment[7]. Conversely, patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) had a significant tendency to lower remission than patients without SSRIs[7]. Such differences in drug response of the bipolar spectrum in comparison to unipolar depression (assumed to respond to antidepressants) may also reflect a boundary between bipolar spectrum and unipolar depression.

As aforementioned, Akiskal et al[2] conceptualized bipolar IV disorder as part of the bipolar spectrum, which is seen in individuals with long-standing and stable hyperthymic temperaments into which a major depressive episode intrudes. As to the potential biological basis of the hyperthymic temperament, Rihmer et al[4] suggested dopaminergic dysregulation, while Savitz et al[8] showed that the Met allele of brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism was associated with higher hyperthymic temperament scores.

Hoaki et al[9] have investigated the hyperthymic temperament by using actigraphy to measure daytime illuminance and by performing a serotonergic neuroendocrine challenge test. Using stepwise regression analysis, three variables were determined as independent predictors for hyperthymic temperament scores: illuminance of daytime, serotonergic function as estimated by the neuroendocrine challenge test, and variance of sleep time. These variables explained 33.0% of hyperthymic temperament scores, suggesting that light, sleep and serotonin are crucial biological factors in association with the hyperthymic temperament.

The (Soft) Bipolar spectrum is a concept which bridges bipolar I disorder and unipolar depression. As Kraepelin[1] described, there may be continuity across mood disorders. If this is the case, why we should discriminate for drug choice For example, mood stabilizers are used for bipolar spectrum patients as well as bipolar I disorder patients, whereas antidepressants are prescribed for patients with unipolar depression. If these entities are diagnostically continuous, the same drug would be expected to be effective for both the bipolar spectrum and unipolar depression. This prediction forms the basis of my hypothesis that there is an inflexion point at the boundary between the bipolar spectrum and unipolar depression (Figure 1) and, as mentioned in Goto et al[7], temperaments may consist of this inflexion point. Moreover, as demonstrated in Hoaki et al[9], the hyperthymic temperament has several biological factors which may be associated with drug response. Therefore, whilst the concept of bipolar spectrum emphasizes continuity, it is possible that an inflexion point exists which determines/discriminates changes in drug response. At the moment, this is just a hypothesis, but I believe that this idea is worthy of further research.

Peer reviewer: Thomas Frodl, MD, MA, Professor, Habilitation, Department of Psychiatry, University Dublin, Trinity College, Trinity Centre for Health Research, Adelaide and Meath Hospital Incorporating the National Children’s Hospital, Dublin 24, Ireland

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Zivanovic O, Nedic A. Kraepelin's concept of manic-depressive insanity: one hundred years later. J Affect Disord. 2012;137:15-24. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Akiskal HS, Pinto O. The evolving bipolar spectrum. Prototypes I, II, III, and IV. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1999;22:517-534, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Akiskal HS. The emergence of the bipolar spectrum: validation along clinical-epidemiologic and familial-genetic lines. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2007;40:99-115. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Rihmer Z, Akiskal KK, Rihmer A, Akiskal HS. Current research on affective temperaments. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:12-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Akiskal HS, Mallya G. Criteria for the "soft" bipolar spectrum: treatment implications. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1987;23:68-73. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Akiskal HS. Toward a temperament-based approach to depression: implications for neurobiologic research. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1995;49:99-112. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Goto S, Terao T, Hoaki N, Wang Y. Cyclothymic and hyperthymic temperaments may predict bipolarity in major depressive disorder: a supportive evidence for bipolar II1/2 and IV. J Affect Disord. 2011;129:34-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Savitz J, van der Merwe L, Ramesar R. Personality endophenotypes for bipolar affective disorder: a family-based genetic association analysis. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:869-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hoaki N, Terao T, Wang Y, Goto S, Tsuchiyama K, Iwata N. Biological aspect of hyperthymic temperament: light, sleep, and serotonin. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;213:633-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |