Published online Jun 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i6.106017

Revised: March 28, 2025

Accepted: April 21, 2025

Published online: June 19, 2025

Processing time: 104 Days and 8.5 Hours

Adolescence is a period marked by physiological and psychological imbalances, which pose an increased risk for adolescents with major depressive disorder (MDD) to commit non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI).

To investigate the moderating role of social support utilization in depression and NSSI among adolescents with MDD.

This cross-sectional study enrolled 314 adolescents with MDD (258 with NSSI, 56 without) from a Chinese tertiary psychiatric hospital (2021-2023). Participants completed validated scales, including the self-esteem scale, the Barratt impulsiveness scale, the self-rating depression scale, and the teenager social support rating scale. Logistic regression and hierarchical regression analyses were used to examine predictors of NSSI and the moderating effect of social support utilization.

Results showed that the NSSI group had higher depression levels, lower self-esteem, and greater impulsivity. While overall social support was higher in the NSSI group, social support utilization significantly moderated the depression-NSSI relationship. Specifically, higher utilization levels weakened the association between depression and NSSI (β = -0.001, P < 0.05).

These findings suggest that effective utilization of social support, rather than its mere presence, is crucial in redu

Core Tip: This study explores the link between depression and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents with major depressive disorder, highlighting the crucial role of social support utilization. It reveals that while the mere presence of social support may not suffice, effective utilization of such support can significantly weaken the association between depression and NSSI. The findings emphasize the need for interventions aimed at enhancing adolescents' ability to utilize social support and culturally informed approaches to reduce NSSI risk.

- Citation: Hu JT, Cao Y, Liu LL, Wang D, Zhu P, Du X, Ji F, Peng RJ, Tian Q, Zhu F. Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: The moderating influence of social support utilization on depression. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(6): 106017

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i6/106017.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i6.106017

Adolescence constitutes a developmental period characterized by physiological and psychological imbalances. The misalignment between physical and mental maturation, combined with emergent adult identity conflicts, creates vulnerability to mental health issues. Depression, frequently originating in childhood, intensifies during adolescence[1]. Global statistics indicate that 20% of youth experience depression or depressive symptoms[2]. Research indicates that between 2001 and 2020, the global point prevalence of elevated self-reported depressive symptoms among adolescents was 34%, with point prevalence rates of 8% for major depressive disorder (MDD) and 19% for dysthymia. Furthermore, the reported point prevalence of depressive symptoms in adolescents increased significantly over time, rising from 24% between 2001 and 2010 to 37% between 2010 and 2020. Notably, female adolescents in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia exhibited the highest risk of depressive disorders, underscoring substantial disparities across genders and cultural contexts[3]. Depression manifests in interpersonal difficulties, academic deterioration, career challenges, and diminished quality of life, while increasing risks of recurrence, self-harm, and suicide[4]. In China, depression represents the predominant mood disorder and second leading cause of disability, substantially impacting global disease burden[5].

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) encompasses intentional self-harming behaviors without suicidal intent[6]. Classified as a distinct psychological condition in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), NSSI typically emerges at age 13. Global lifetime prevalence stands at 17.7%[7], with adolescent rates varying between 13.0% and 46.5%[8]. The escalating prevalence and recurrence rates pose significant threats to adolescent health and serve as robust predictors of suicidal behavior. Despite its severity as the fourth leading cause of adolescent mortality[9], NSSI often remains concealed, with affected individuals reluctant to seek intervention. The condition demonstrates heightened prevalence among those with depression and borderline personality disorder[10,11]. Evidence indicates strong associations between NSSI and depressive symptomatology, particularly in severe cases[12], with depression functioning as an independent risk factor[13]. These findings necessitate targeted interventions for adolescents experiencing both depression and NSSI.

Beyond depression, NSSI risk factors span biological, psychological, familial, and social domains. Indeed, meta-analytic findings[8] highlight psychological risk factors including psychiatric disorders, emotional distress, compromised self-esteem, body image disturbance, emotional dysregulation, maladaptive coping, cognitive vulnerability, addiction, impulsivity, and unmet psychological needs. Family-level factors comprise dysfunctional parent-child dynamics, inappropriate parenting practices, adverse experiences, and limited parental engagement. Social determinants include peer relationships, school environment, interpersonal conflicts, discrimination, and resource accessibility. Research demonstrates the mediating role of depression between social stress and NSSI in adolescents[14]. The stress-buffering hypothesis[15] proposes that social support moderates stress-health relationships, potentially mitigating depression risk[16] and NSSI development[17]. However, individuals engaging in NSSI frequently report insufficient perceived social support[18,19]. These findings suggest that enhancing support systems and their utilization may reduce both depressive symptoms and NSSI incidence. However, current research on the moderating role of social support utilization between depression and NSSI remains limited. Therefore, this study investigates its moderating effect on NSSI.

Based on these findings, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between psychosocial characteristics (including depression, self-esteem, impulsivity, and social support) and NSSI among adolescents, with a particular focus on the moderating role of social support utilization. Specifically, this study addresses two critical gaps: (1) The unclear mechanisms through which social support utilization (rather than its mere presence) moderates the depression-NSSI relationship; and (2) The lack of strategies in existing NSSI interventions to enhance adolescents’ ability to utilize social support, especially within China’s sociocultural context. We hypothesized that higher levels of depression and impulsivity, along with lower self-esteem, would increase the risk of NSSI, while social support (including subjective support, objective support, and support utilization) might reduce this risk. Understanding these relationships could inform the development of more comprehensive psychosocial interventions for adolescents at risk of self-harm. By clarifying these mechanisms and providing empirical evidence, this study aims to inform culturally tailored interventions for policymakers and clinicians, ultimately contributing to reducing NSSI prevalence among Chinese adolescents.

This study was conducted at Suzhou Guangji Hospital, Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, People's Republic of China from January 2021 to December 2023, following Helsinki Declaration guidelines and institutional ethics committee approval. Participants were recruited through consecutive sampling from outpatient and inpatient psychiatric departments. To ensure representativeness, adolescents with MDD were screened across multiple hospital departments (e.g., psychology, pediatrics). The study enrolled 258 adolescents with MDD and NSSI (NSSI group) and 56 adolescents with MDD without NSSI (non-NSSI group), with written informed consent obtained from all participants and their legal guardians. Demographic data, clinical characteristics, and psychological measures were collected from all participants.

Participants were evaluated using the structured clinical interview for DSM disorders to confirm their diagnostic status. For comprehensive assessment of depressive symptoms, both groups completed the self-rating depression scale (SDS). Study inclusion criteria for both groups specified: Participants aged 12-18 years meeting DSM-5 criteria for MDD. The NSSI group additionally fulfilled DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for NSSI, including ≥ 5 episodes of intentional self-harm without suicidal intent in the past 12 months. Exclusion criteria included: Serious physical/neurological conditions, substance use disorders (except tobacco), and psychotic disorders.

The study employed validated psychological instruments to assess participants' mental health profiles. The Rosenberg self-esteem scale[20], a 10-item measure using a 4-point Likert scale, evaluated global self-esteem, with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem. The scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach's α = 0.817). The Barratt impulsiveness scale (BIS-11)[21], a 30-item self-report questionnaire with established reliability and validity among adolescents, measured impulsiveness across attentional, motor, and non-planning dimensions. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency in the current sample for the total score (Cronbach's α = 0.826) and its subscales (attentional α = 0.802, motor α = 0.800, non-planning α = 0.797). Furthermore, the reliability and validity of the BIS-11 among Chinese adolescents have been established in previous research, demonstrating good reliability (Cronbach's α reported as 0.80) and supporting criterion validity through significant positive correlations between the BIS-11 total score and measures like the risky behaviors questionnaire-adolescents score (r = 0.31, P < 0.01)[22]. The SDS[23] assessed the frequency and severity of depressive symptoms through 20 items. Internal consistency for the SDS in this study was acceptable (Cronbach's α = 0.741). Social support was measured using the teenager social support rating scale (TSSRS), which evaluates subjective support, objective support, and support utilization. Although originally developed for university students[24], the TSSRS has been validated for adolescent populations[25]. Prior research[25,26] has confirmed its psychometric properties; reported internal consistency coefficients included a Cronbach's alpha of 0.884 for the total scale, 0.824 for Subjective Support, 0.801 for Objective Support, and 0.822 for Support Utilization. Furthermore, exploratory factor analysis in those studies supported its theoretical structure, explaining 61.412% of the total variance. The TSSRS also demonstrated good to excellent internal consistency in our study, with Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.907 for the total scale, 0.846 for subjective support, 0.846 for Objective Support, and 0.844 for Support Utilization. A custom demographic questionnaire gathered data on age, gender, education level, family economic status, parental education, and childhood adversity.

Measures were administered in participants' native language, with trained research assistants available for clarification. To minimize order effects, questionnaire administration was randomized. Participants completed the assessments in a private setting to ensure confidentiality.

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.2 (R Core Team, 2021, https://www.r-project.org/). Descriptive statistics included means, standard deviations, and frequencies for all variables. Given the different data types and research questions, specific tests were chosen: Welch's t-tests and χ2 tests compared demographic and clinical characteristics between the NSSI and non-NSSI groups. However, due to unequal sample sizes and to provide a robust comparison without assuming normal distribution, permutation tests with 10000 iterations examined group differences in psychological measures. Bivariate relationships between key psychological variables were examined using Pearson correlation coefficients, with statistical significance assessed via permutation testing (10000 iterations). Logistic regression analysis (using a stepwise approach) was chosen to investigate predictors of the dichotomous self-harm behavior variable (group membership: 0 = non-NSSI, 1 = NSSI), assessing the influence of depression, impulsiveness, social support, and demographic variables. Multicollinearity for the final logistic regression model was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIFs) calculated via the car package (version 3.1-3, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/car/index.html) in R; VIF values below 5 were considered acceptable.

Cronbach's α was calculated and hierarchical regression analysis was conducted using the bruceR (Version 2024.6, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/bruceR/index.html) package. The hierarchical regression examined the moderating effect of social support utilization on the depression-self-harm relationship. Model 1 included the main effect of depression, and Model 2 added social support utilization and the depression × social support utilization interaction term. Simple slope analysis evaluated depression's effect on self-harm at different social support utilization levels (-1 SD, mean, +1 SD). The Johnson-Neyman technique identified the range of social support utilization values where the depression-self-harm relationship was significant.

All tests were two-tailed with significance set at P < 0.05. The false discovery rate correction controlled for multiple comparisons within each analysis.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between the non-NSSI (n = 56) and NSSI (n = 258) groups (Table 1). The mean age in the non-NSSI group (14.5 ± 1.8 years) was marginally higher than the NSSI group (14.1 ± 1.5 years), though not significantly different (t = 2.8, P = 0.216). Gender distribution differed significantly between groups (χ² = 12.1, P = 0.011), with higher female representation in the NSSI group. The groups showed no significant differences in only-child status, grade distribution, study status, academic performance, or interpersonal relationship quality. Socioeconomic indicators, including family economic status and parental education levels, were comparable between the groups. Childhood adversity prevalence was also similar between the two groups.

| Variables | Non-NSSI (n = 56) | NSSI (n = 258) | t/χ² | P value |

| Age, mean (SD) | 14.5 (1.8) | 14.1 (1.5) | 2.8 | 0.216 |

| Gender | 12.1 | 0.011a | ||

| Male | 20 (35.7) | 38 (14.7) | ||

| Female | 36 (64.3) | 220 (85.3) | ||

| Only child | 4.6 | 0.114 | ||

| No | 24 (42.9) | 154 (59.7) | ||

| Yes | 32 (57.1) | 104 (40.3) | ||

| Grade | 4.2 | 0.216 | ||

| Primary | 4 (7.1) | 31 (12.0) | ||

| Junior | 36 (64.3) | 182 (70.5) | ||

| Senior | 16 (28.6) | 45 (17.4) | ||

| Study status | 9.2 | 0.157 | ||

| In school | 17 (30.4) | 42 (16.3) | ||

| Suspension | 10 (17.9) | 74 (28.7) | ||

| Leave | 26 (46.4) | 136 (52.7) | ||

| Return | 2 (3.6) | 5 (1.9) | ||

| Dropout | 1 (1.8) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Academic performance | 2.0 | 0.458 | ||

| Top third | 12 (21.4) | 63 (24.4) | ||

| Middle third | 35 (62.5) | 136 (52.7) | ||

| Bottom third | 9 (16.1) | 59 (22.9) | ||

| Interpersonal relationships | 7.3 | 0.114 | ||

| Good | 17 (30.4) | 57 (22.1) | ||

| Average | 32 (57.1) | 124 (48.1) | ||

| Poor | 7 (12.5) | 77 (29.8) | ||

| Economic status | 4.4 | 0.458 | ||

| Much better | 2 (3.6) | 9 (3.5) | ||

| Better | 20 (35.7) | 75 (29.1) | ||

| Average | 31 (55.4) | 143 (55.4) | ||

| Worse | 1 (1.8) | 25 (9.7) | ||

| Much worse | 2 (3.6) | 6 (2.3) | ||

| Father's education | 2.7 | 0.601 | ||

| ≤ Junior high | 22 (39.3) | 85 (32.9) | ||

| Senior high | 11 (19.6) | 75 (29.1) | ||

| College | 10 (17.9) | 43 (16.7) | ||

| Bachelor | 10 (17.9) | 47 (18.2) | ||

| ≥ Master | 3 (5.4) | 8 (3.1) | ||

| Mother's education | 4.5 | 0.458 | ||

| ≤ Junior high | 22 (39.3) | 98 (38.0) | ||

| Senior high | 12 (21.4) | 76 (29.5) | ||

| College | 10 (17.9) | 42 (16.3) | ||

| Bachelor | 8 (14.3) | 36 (14.0) | ||

| ≥ Master | 4 (7.1) | 6 (2.3) | ||

| Childhood adversity | 0.8 | 0.458 | ||

| No | 17 (30.4) | 98 (38.0) | ||

| Yes | 39 (69.6) | 160 (62.0) |

Gender emerged as the sole significantly different variable between the groups, with females comprising 85.3% of the NSSI group compared with 64.3% of the non-NSSI group. This finding suggests gender as a potential key factor in NSSI.

Permutation tests with 10000 iterations compared psychological measures between the non-NSSI and NSSI groups, addressing the unequal sample sizes and avoiding distributional assumptions. Table 2 reveals significant differences across all psychological variables. The NSSI group demonstrated lower self-esteem (P < 0.001) and higher depression levels (P < 0.001) compared to the non-NSSI group. The NSSI group also showed elevated overall impulsiveness (P < 0.001) on the BIS-11, with significant differences across attentional (P < 0.001), motor (P = 0.025), and non-planning (P = 0.006) dimensions. These findings align with previous research on psychological profiles of individuals engaging in NSSI[8].

| Variables | Non-NSSI (n = 56) | NSSI (n = 258) | F | P values |

| SES (self-esteem) | 24.8 (6.4) | 21.1 (4.9) | 24.8 | < 0.001c |

| BIS (impulsiveness) | 63.2 (10.6) | 68.7 (8.8) | 17.8 | < 0.001c |

| Attentional impulsiveness | 14.8 (3.5) | 16.9 (3.1) | 21.9 | < 0.001c |

| Motor impulsiveness | 20.2 (3.9) | 21.5 (3.7) | 5.2 | 0.025a |

| Non-planning impulsiveness | 25.9 (5.2) | 27.8 (4.4) | 8.1 | 0.006b |

| SDS (depression) | 27.5 (7.6) | 33.2 (6.2) | 37.0 | < 0.001c |

| TSSRS (social support) | 47.5 (17.8) | 55.4 (15.2) | 13.4 | < 0.001c |

| Subjective support | 13.8 (6.3) | 16.5 (5.3) | 14.3 | < 0.001c |

| Objective support | 14.6 (6.3) | 17.5 (5.9) | 10.7 | 0.002b |

| Support utilization | 19.1 (7.4) | 21.5 (6.4) | 6.5 | 0.013a |

The NSSI group reported higher overall social support (P < 0.001) across all TSSRS subscales: Subjective support (P < 0.001), objective support (P = 0.002), and support utilization (P = 0.013). This unexpected finding may reflect increased help-seeking behaviors or heightened attention following NSSI. Wu et al[27] suggested that individuals engaging in self-harm may perceive greater support due to increased awareness of available resources post-intervention.

Stepwise logistic regression analyzed predictors of NSSI, which were coded dichotomously (0 = non-NSSI, 1 = NSSI). Next, from 13 initial predictors including depression, impulsiveness dimensions, social support components, education level, age, and gender, five were retained: Depression, education level, attention impulsiveness, social support utilization, and overall social support. Prior to the logistic regression analyses, correlations among key variables were examined (Supplementary Table 1); notably, NSSI group membership showed expected associations (e.g., with lower self-esteem, higher impulsivity/depression) but also unexpected positive links with reported social support. Multicollinearity checks using VIFs for the final logistic regression model indicated acceptable levels (all VIFs < 5), supporting the model's stability. The final model (Table 3) was found to be significant [χ² (5) = 41.31, P < 0.001], explaining 20.3% of NSSI variance (Nagelkerke R²). Depression and social support utilization emerged as significant predictors. Depression was positively correlated with NSSI group membership [β = 0.12, SE = 0.03, Wald = 3.70, P < 0.001, OR = 1.13, 95%CI (1.06, 1.21)], with each unit increase raising NSSI odds by 13%. Conversely, social support utilization was negatively correlated with NSSI group membership [β = -0.11, SE = 0.05, Wald = -2.04, P = 0.041, OR = 0.90, 95%CI (0.81, 0.99)], with each unit increase reducing NSSI odds by 10%.

| Variables | β | SE | Wald | P value | OR | 95%CI for OR |

| Depression (SDS score) | 0.12 | 0.03 | 3.70 | < 0.001c | 1.13 | [1.06, 1.21] |

| Education level | -0.42 | 0.29 | -1.44 | 0.150 | 0.65 | [0.37, 1.16] |

| Attention impulsiveness (BIS) | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.42 | 0.156 | 1.09 | [0.97, 1.23] |

| Social support utilization (TSSRS) | -0.11 | 0.05 | -2.04 | 0.041a | 0.90 | [0.81, 0.99] |

| Overall social support (TSSRS) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.43 | 0.153 | 1.03 | [0.99, 1.07] |

Education level, attention impulsiveness, and overall social support remained non-significant predictors (P > 0.05), though their retention suggests potential influence on NSSI group membership. These findings underscore the significant roles of depression and social support utilization in predicting NSSI, while also highlighting the complex nature of distinguishing between NSSI and non-NSSI individuals. The results provide potential targets for intervention and prevention strategies, emphasizing the importance of addressing depressive symptoms and enhancing social support utilization in populations at risk for NSSI.

We next examined how social support utilization (moderating variable) influences the relationship between depression (independent variable) and NSSI (dependent variable). As shown in Table 4, hierarchical regression analysis revealed a significant interaction between depression and social support utilization in predicting NSSI (β = -0.001, SE = 0.000, P < 0.05), indicating a moderating effect. The initial model, which included only depression as a predictor, accounted for 10.2% of the variance in NSSI (R² = 0.102). The addition of social support utilization and its interaction term with depression in the second model led to a small but significant increase in the explained variance (ΔR² = 0.016, F for ΔR² = 3.900, P < 0.05), with the full model accounting for 11.8% of the variance in NSSI (R² = 0.118). These results provide initial evidence for the moderating role of social support utilization.

To further elucidate this moderating effect, a simple slope analysis was conducted examining the effect of depression (independent variable) on NSSI (dependent variable) at different levels of social support utilization (moderating variable). As presented in Table 5 and visually depicted in Figure 1, at low levels of social support utilization (-1 SD), depression had the strongest positive effect on NSSI (effect = 0.025, SE = 0.004, P < 0.001, 95%CI: 0.017, 0.033). This effect remained significant but decreased at medium levels of social support utilization [effect = 0.020, SE = 0.004, P < 0.001, 95%CI (0.012, 0.027)], and further reduced at high levels [effect = 0.015, SE = 0.005, P = 0.003, 95%CI (0.005, 0.024)]. These results clearly demonstrate the moderating effect of social support utilization, i.e., as the level of social support utilization increases, the impact of depression on NSSI gradually weakens.

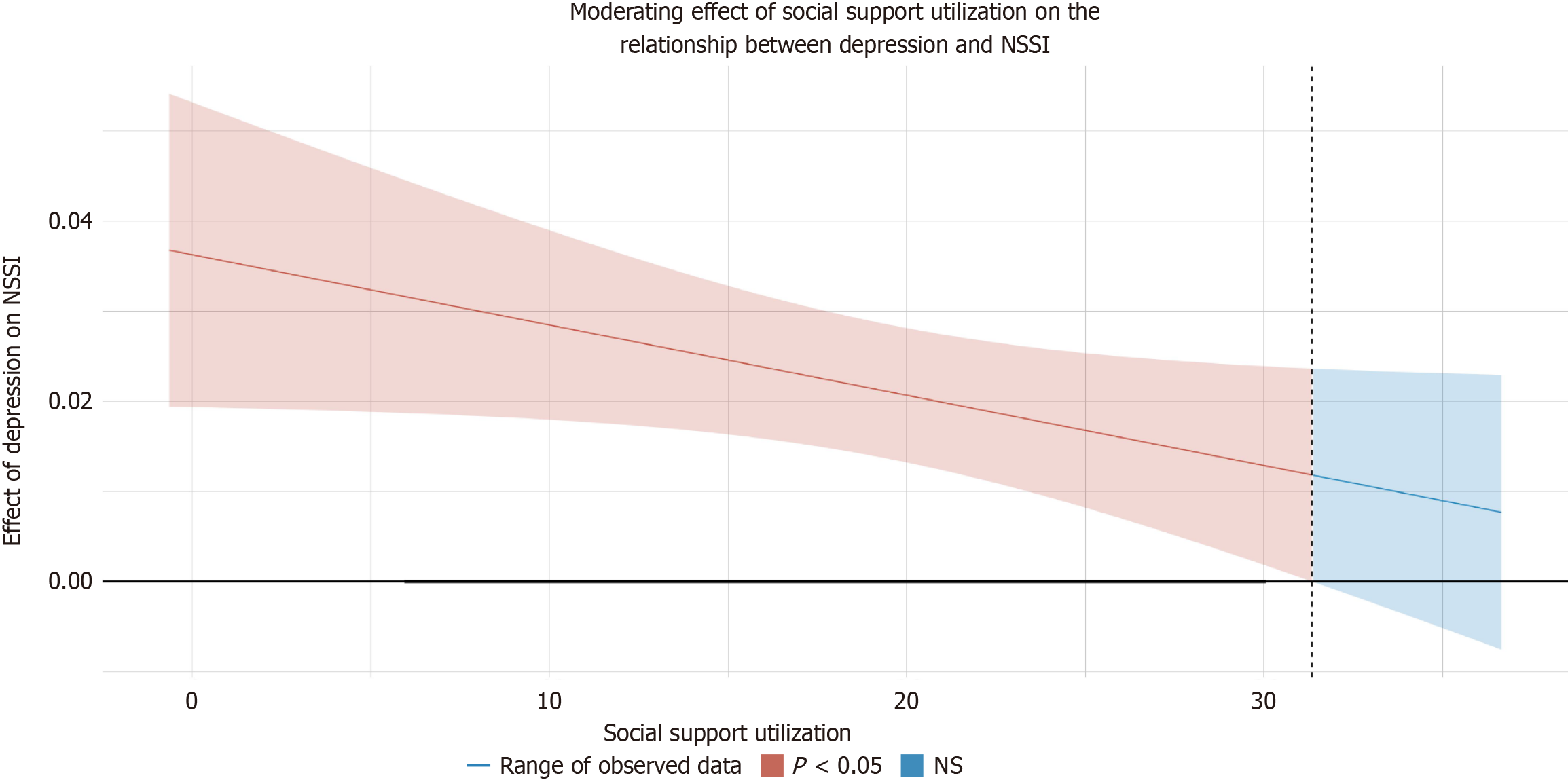

Figure 2 presents a Johnson-Neyman plot, which further illustrates the conditional effect of depression on NSSI across different levels of social support utilization. The plot shows that the effect of depression on NSSI remains significant but decreases as social support utilization increases, as indicated by the downward slope of the line.

These findings indicate that social support utilization, as a moderating variable, significantly moderated the relationship between depression (independent variable) and NSSI (dependent variable). Specifically, the moderating effect manifested as follows: While depression remained a significant predictor of NSSI across all levels of social support utilization, the strength of this relationship weakened as social support utilization increased. This moderating effect highlights the potential protective role of social support utilization in mitigating the impact of depression on NSSI, although it does not completely negate the relationship between depression and NSSI.

This study investigated the moderating role of social support utilization on the relationship between depression and NSSI among adolescents with MDD. Our primary objectives were to examine psychological and social support differences between NSSI and non-NSSI individuals and evaluate how social support utilization influences the depression-NSSI relationship. The findings revealed significant group differences in psychological characteristics, with NSSI individuals demonstrating higher depression levels, lower self-esteem, and greater impulsivity across all dimensions. Notably, while the NSSI group reported higher overall social support, the effectiveness of support utilization emerged as a crucial moderating factor. The hierarchical regression analysis demonstrated that social support utilization significantly moderated the relationship between depression and NSSI, with higher utilization levels weakening the depression-NSSI association. These results suggest that the mere presence of social support may be insufficient to protect against NSSI; rather, the active and effective utilization of available support resources appears to be the key factor in reducing self-harm risk among depressed adolescents. Clinically, we recommend integrating brief social support utilization training (e.g., role-playing help-seeking scenarios, identifying trusted support figures) into cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) sessions. For policymakers, embedding mental health literacy modules in school curricula such as teaching adolescents to articulate emotional needs through structured exercises could also enhance support engagement. Specifically, support utilization levels showed a significant negative correlation with NSSI frequency, a relationship that remained stable after controlling for demographic variables. Moreover, the moderating effect of support utilization was more pronounced among individuals with high depressive symptoms, highlighting the importance of strengthening support utilization skills in clinical interventions. Multiple regression analyses further revealed that improvements in support utilization capacity were associated with significant reductions in self-injurious behaviors, a relationship that remained consistent across age groups and genders.

Our findings extend current understanding of the complex interplay between depression, social support, and NSSI in several important ways. The higher depression scores and lower self-esteem in the NSSI group align with previous research identifying these as risk factors for self-injurious behaviors[28]. However, the unexpected finding of higher reported social support in the NSSI group challenges traditional assumptions about support deficits in self-harming individuals. This paradoxical finding warrants careful interpretation through multiple lenses. First, it may reflect increased help-seeking behaviors or heightened awareness of support resources following clinical intervention, consistent with the observations of Wu et al[27]. Second, the higher reported support could represent a compensatory mechanism, where individuals with NSSI histories have received intensified support from both formal and informal sources in response to their self-injurious behaviors, potentially reflecting heightened parental vigilance and involvement for adolescents with NSSI. The moderating effect of support utilization suggests that the mere presence of support resources may be insufficient; rather, the active engagement with available support systems appears crucial in buffering against NSSI risk.

The theoretical implications of our findings support and expand upon both the stress-buffering hypothesis[29] and interpersonal models of NSSI[30,31]. The demonstrated moderating effect of support utilization provides empirical evidence for the protective role of active support engagement in reducing NSSI risk, particularly among depressed adolescents. This finding aligns with recent research on emotion regulation and social support while extending these frameworks to NSSI specifically[32-35]. Our results suggest that theoretical models of NSSI should incorporate not only the availability of social support but also the individual's capacity and willingness to utilize available resources effectively. The finding that social support utilization moderates the depression-NSSI relationship adds a crucial dimension to existing vulnerability-stress models, suggesting that intervention strategies should focus not only on increasing support availability but also on enhancing individuals' support utilization skills. Furthermore, our results contribute to the growing body of literature examining the role of social support in Asian cultural contexts, where family dynamics and social hierarchies may influence support-seeking behaviors differently than in Western societies. This cultural perspective adds valuable nuance to existing theoretical frameworks and highlights the need for culturally informed modifications to both theory and practice. Path analysis further revealed a complex mediation model where support utilization influenced NSSI risk through enhanced emotion regulation capacity and improved problem-solving efficacy. This finding deepens our understanding of the mechanisms through which support utilization exerts its protective effects, and suggests multiple psychological pathways are at play.

Several methodological limitations warrant consideration when interpreting these findings. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences about the relationships between depression, social support utilization, and NSSI. While our statistical analyses accounted for the unequal sample sizes between the NSSI and non-NSSI groups through appropriate methods, this imbalance may have influenced the results in ways that require further investigation. The reliance on self-reported measures introduces potential reporting biases, particularly regarding sensitive topics like self-harm and depression. The hospital-based sample may limit generalizability to community populations, and cultural factors specific to Chinese adolescents should be considered when extending findings to other cohorts. Additionally, our measurement of social support utilization, while validated, may not capture all relevant aspects of how adolescents engage with support resources, particularly in the context of modern digital communication platforms. The potential influence of medication and other concurrent treatments on participants' support utilization patterns represents another limitation that future studies should address through more controlled designs.

Future research should prioritize three directions based on this study’s findings and limitations: (1) Longitudinal validation of social support utilization’s long-term protective effects on NSSI, particularly testing whether early skill-building interventions (e.g., role-playing sessions in CBT) sustain reduced self-harm rates beyond 12 months; (2) Digital support mechanisms, such as AI-driven chatbots (e.g., Woebot) or VR-based peer interaction platforms, should be empirically evaluated for their efficacy in enhancing support utilization among adolescents with high depression severity; and (3) Cross-cultural comparative studies must disentangle how collectivist family dynamics in China vs individualist societies modulate support utilization patterns, using mixed-method designs (e.g., ecological momentary assessment + qualitative interviews). Methodologically, multisource data (e.g., wearable devices tracking physiological stress + caregiver reports) should supplement self-reports to reduce bias.

This study identifies social support utilization as a critical moderator of the depression-NSSI relationship in adolescents diagnosed with MDD, demonstrating that effective engagement with support resources (rather than their mere availability) reduces self-harm risk. These findings advance theoretical frameworks by integrating support utilization into vulnerability-stress models and highlight culturally tailored interventions, including skill-building programs for support access, as key strategies.

| 1. | Krause KR, Chung S, Adewuya AO, Albano AM, Babins-Wagner R, Birkinshaw L, Brann P, Creswell C, Delaney K, Falissard B, Forrest CB, Hudson JL, Ishikawa SI, Khatwani M, Kieling C, Krause J, Malik K, Martínez V, Mughal F, Ollendick TH, Ong SH, Patton GC, Ravens-Sieberer U, Szatmari P, Thomas E, Walters L, Young B, Zhao Y, Wolpert M. International consensus on a standard set of outcome measures for child and youth anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:76-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lu B, Lin L, Su X. Global burden of depression or depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2024;354:553-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CHJ. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61:287-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 572] [Article Influence: 143.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Thapar A, Eyre O, Patel V, Brent D. Depression in young people. Lancet. 2022;400:617-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 124.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lu J, Xu X, Huang Y, Li T, Ma C, Xu G, Yin H, Xu X, Ma Y, Wang L, Huang Z, Yan Y, Wang B, Xiao S, Zhou L, Li L, Zhang Y, Chen H, Zhang T, Yan J, Ding H, Yu Y, Kou C, Shen Z, Jiang L, Wang Z, Sun X, Xu Y, He Y, Guo W, Jiang L, Li S, Pan W, Wu Y, Li G, Jia F, Shi J, Shen Z, Zhang N. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:981-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 477] [Cited by in RCA: 438] [Article Influence: 109.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang YJ, Li X, Ng CH, Xu DW, Hu S, Yuan TF. Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents: A meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;46:101350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Moloney F, Amini J, Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Lanctôt KL, Mitchell RHB. Sex Differences in the Global Prevalence of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2415436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Qu D, Wen X, Liu B, Zhang X, He Y, Chen D, Duan X, Yu J, Liu D, Zhang X, Ou J, Zhou J, Cui Z, An J, Wang Y, Zhou X, Yuan T, Tang J, Yue W, Chen R. Non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese population: a scoping review of prevalence, method, risk factors and preventive interventions. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023;37:100794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Plener PL, Kaess M, Schmahl C, Pollak S, Fegert JM, Brown RC. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in Adolescents. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Dubicka B, Goodyer I. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT). Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:495-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Min J, Hein KE, Medlin AR, Mullins-Sweatt SN. Prevalence rate trends of borderline personality disorder symptoms and self-injurious behaviors in college students from 2017 to 2021. Psychiatry Res. 2023;329:115526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Burke TA, Fox K, Zelkowitz RL, Smith DMY, Alloy LB, Hooley JM, Cole DA. Does nonsuicidal self-injury prospectively predict change in depression and self-criticism? Cognit Ther Res. 2019;43:345-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jiao T, Guo S, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xie X, Ma Y, Chen R, Yu Y, Tang J. Associations of depressive and anxiety symptoms with non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal attempt among Chinese adolescents: The mediation role of sleep quality. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1018525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu N, Hou Y, Zeng Q, Cai H, You J. Bullying Experiences and Nonsuicidal Self-injury among Chinese Adolescents: A Longitudinal Moderated Mediation Model. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50:753-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310-357. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Axinn WG, Choi KW, Ghimire DJ, Cole F, Hermosilla S, Benjet C, Morgenstern MC, Lee YH, Smoller JW. Community-Level Social Support Infrastructure and Adult Onset of Major Depressive Disorder in a South Asian Postconflict Setting. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mackin DM, Perlman G, Davila J, Kotov R, Klein DN. Social support buffers the effect of interpersonal life stress on suicidal ideation and self-injury during adolescence. Psychol Med. 2017;47:1149-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wolff JC, Frazier EA, Esposito-Smythers C, Becker SJ, Burke TA, Cataldo A, Spirito A. Negative cognitive style and perceived social support mediate the relationship between aggression and NSSI in hospitalized adolescents. J Adolesc. 2014;37:483-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Claes L, Bouman WP, Witcomb G, Thurston M, Fernandez-Aranda F, Arcelus J. Non-suicidal self-injury in trans people: associations with psychological symptoms, victimization, interpersonal functioning, and perceived social support. J Sex Med. 2015;12:168-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | de Kleine RA, Woud ML, Ferentzi H, Hendriks GJ, Broekman TG, Becker ES, Van Minnen A. Appraisal-based cognitive bias modification in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomised clinical trial. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019;10:1625690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:768-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yang H, Yang HQ, Yao SQ, Zhu XZ, Auerbach RP, Abela JRZ. [Reliability and Validity Analysis of the Chinese Version of Barratt Impulsiveness Scale in Middle School Students]. Zhongguo Linchuang Xinlixue Zazhi. 2007;6+12. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5900] [Cited by in RCA: 6052] [Article Influence: 208.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ye Y, Dai X. [Development of a Social Support Rating Scale for College Students]. Zhongguo Linchuang Xinlixue Zazhi. 2008;16:456-458. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Dai JJ, Mo X, Wang HR, Lv SX. [The Relationship Between Adolescents' Social Support Systems and Mental Health Levels: A Case Study of Nantong City, Jiangsu Province]. Hngxiaoxue Xinli Jiankang Jiaoyu. 2008;21:10-12,15. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Wang X, Li L, Mu S. [The Impact of Social Support on Life Satisfaction in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model]. Xinan Shifan Daxue Xuebao (Ziran Kexue Ban). 2016;29:107-113. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Wu CY, Stewart R, Huang HC, Prince M, Liu SI. The impact of quality and quantity of social support on help-seeking behavior prior to deliberate self-harm. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Garisch JA, Wilson MS. Prevalence, correlates, and prospective predictors of non-suicidal self-injury among New Zealand adolescents: cross-sectional and longitudinal survey data. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2015;9:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Field RJ, Schuldberg D. Social-support moderated stress: a nonlinear dynamical model and the stress-buffering hypothesis. Nonlinear Dynamics Psychol Life Sci. 2011;15:53-85. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Hepp J, Störkel LM, Wycoff AM, Freeman LK, Schmahl C, Niedtfeld I. A test of the interpersonal function of non-suicidal self-injury in daily life. Behav Res Ther. 2021;144:103930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:885-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 777] [Cited by in RCA: 849] [Article Influence: 40.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lan Z, Pau K, Md Yusof H, Huang X. The Effect of Emotion Regulation on Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Among Adolescents: The Mediating Roles of Sleep, Exercise, and Social Support. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:1451-1463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Guérin-Marion C, Martin J, Lafontaine MF, Bureau JF. Invalidating Caregiving Environments, Specific Emotion Regulation Deficits, and Non-suicidal Self-injury. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2020;51:39-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Xin M, Zhang L, Yang C, Yang X, Xiang M. Risky or protective? Online social support's impact on NSSI amongst Chinese youth experiencing stressful life events. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kellerman JK, Millner AJ, Joyce VW, Nash CC, Buonopane R, Nock MK, Kleiman EM. Social Support and Nonsuicidal Self-injury among adolescent Psychiatric Inpatients. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2022;50:1351-1361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |