Published online Jun 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i6.105934

Revised: April 9, 2025

Accepted: May 7, 2025

Published online: June 19, 2025

Processing time: 107 Days and 19.5 Hours

Auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs) are believed to be characteristic symptoms of schizophrenia. The prevalence of AVHs in deaf patients with schizophrenia is comparable to that in patients with schizophrenia who have normal hearing ability. AVHs in deaf patients with schizophrenia require treatment.

A 22-year-old deaf woman with schizophrenia had experienced AVHs for 3 months. Her psychotic symptoms were not alleviated by antipsychotic medication alone. Modified electroconvulsive therapy in combination with antipsychotic drugs effectively alleviated her AVHs and disorganized behavior. During outpatient follow-up for 6 months, her condition have remained stable, and she has been able to take care of herself.

Treatment with modified electroconvulsive therapy was found to be safe and might be indicated for deaf patients whose symptoms are not well managed with antipsychotic medication alone. Deaf people might be unable to communicate through spoken language; therefore, to make proper diagnoses and provide appropriate treatment for these patients, psychiatrists must have patience and seek to understand patients’ mental state.

Core Tip: Antipsychotics alone have poor efficacy in treating patients with deafness experiencing auditory verbal hallucinations. Our patient’s psychotic symptoms were controlled with antipsychotic drugs combined with electroconvulsive therapy treatment. Antipsychotic drugs plus modified electroconvulsive therapy might therefore be safe for the treatment of deaf patients with auditory verbal hallucinations. During outpatient follow-up for 6 months, her condition have remained stable, and she has been able to take care of herself.

- Citation: Wang J, Li J, Wei YG, Lu XX, Zhang ZH. Efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy in treating auditory verbal hallucinations in a deaf patient with schizophrenia: A case report. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(6): 105934

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i6/105934.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i6.105934

Evidence indicates that schizophrenia, like neurodegenerative diseases[1,2] such as Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease, also involves the central nervous system[3]. Disruptions in the central nervous system’s ability to accurately distinguish thoughts from actual speech and auditory inputs may lead to symptoms such as auditory hallucinations[3]. The prevalence of schizophrenia in deaf individuals is similar to that in the general population[4]. Auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs) are believed to be characteristic symptoms of psychosis, particularly schizophrenia[5]. Although sound-based hallucinations in deaf people might be an unexpected phenomenon, the prevalence of AVHs in deaf patients with schizophrenia is comparable to that among normal-hearing patients with schizophrenia[4,6]. One study has reported a rate of AVHs of approximately 50% among prelingually deaf people with schizophrenia[7]. Prelingual deafness significantly influences the course of schizophrenia[8]. A longitudinal study has shown that prelingually deaf patients with schizophrenia are much more severely affected than normal hearing controls with schizophrenia, in terms of assessment of resident symptoms and social status[9]. Effective treatment is necessary to improve symptoms in this group of patients.

Antipsychotic drugs are the mainstay treatment for schizophrenia with AVHs but are not always effective in treating AVHs[10]. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), a treatment in which electrical stimulation is applied through electrodes usually placed on both sides of the scalp to induce seizures, was introduced in 1938 as a treatment for schizophrenia[11]. ECT is highly effective in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia or those requiring a rapid response[12]. Serious adverse effects associated with ECT are rare, and include cardiac arrhythmias, respiratory distress, prolonged apnea, aspiration, prolonged paralysis and prolonged seizures[13]. Advances in the safety, tolerability and efficacy of modified ECT (MECT) have been made through the use of an aesthetics and muscle relaxants.

Many reports have described diagnosis[14,15], AVHs[16-19] and medication treatment[20] in deaf patients with schizophrenia. However, no reports have described the use of ECT in deaf patients with schizophrenia. In this report, we describe the case of a deaf patient with AVHs. She was treated by an experienced, patient senior-level psychiatrist. However, she showed a poor response to antipsychotic medication alone. To better manage the patient’s symptoms, we first communicated with the patient’s guardian regarding MECT treatment and explained the potential risks. Subsequently, we, together with her guardian, communicated with the patient in written language, and obtained her consent for the treatment. The patient’s guardian then signed a written informed consent form for MECT treatment. The patient’s psychotic symptoms were controlled after MECT treatment in combination with antipsychotic medication. The mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects remain unclear. ECT may induce brain plasticity, manifesting as changes in gray matter volume during the treatment of schizophrenia, through a mechanism distinct from that of antipsychotics. This treatment may ameliorate positive psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia by preferentially targeting limbic brain regions such as the inferior hippocampal gyrus/hippocampus[21]. Our patient did not report any side effects such as dizziness or headaches after the treatment. Combing antipsychotic drugs and MECT therapy might therefore be safe for deaf patients with schizophrenia.

Our patient was a 22-year-old woman who became deaf at approximately the age of 1, because of the use of gentamicin. She had abnormal speech and disorganized behavior, and poor sleep for 3 months.

She was involuntarily admitted to our hospital for treatment. She had been working in another city 3 months before admission. Her mother observed that she was behaving abnormally when during a video chat on WeChat. The patient exhibited winking, made faces, and showed a lack of concentration and difficulty in communicating normally. Her parents went to the city where she worked, and took her home. At home, she subsequently showed erratic behavior, including yelling, kneeling and kowtowing, talking to herself and gesticulating with her hands. Her mother was with her all the time. The patient used sign language to express that she could hear someone talking to her, that she was dying and that the voice ordered her to die. She believed that she was an alien and that her real parents were aliens. She thought that someone was trying to hurt her. She was too afraid to sleep, and she frequently shouted. Before she attended our hospital, her parents had taken her to the local hospital, and she had taken 5 mg olanzapine per day for 1 month with unsatisfactory results.

She had deafness caused by gentamicin use at the age of approximately 1 year.

She had been educated in a special school and had graduated from junior high school. She was able to write and communicate in sign language, and also pronounce simple words. She had no history of substance use and no family history of mental illness within three generations.

A physical examination of various systems revealed no abnormalities except deafness. Through written communication, we found that her thinking was disorganized, that she had AVHs, that she heard voices telling her to die and that she sometimes wrote “dying”. She believed that she was an alien; indicated that she wanted to go back to the outer planets; and believed that there was too much electricity on the Earth and that it was unsafe.

Laboratory examinations, including complete blood count, liver function, renal function, diabetes mellitus lipid profile, cardiac enzyme profile and thyroid function tests, were performed to rule out a secondary organic etiology.

A computed tomography scan of her head yielded normal findings.

According to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision-10 diagnostic system, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

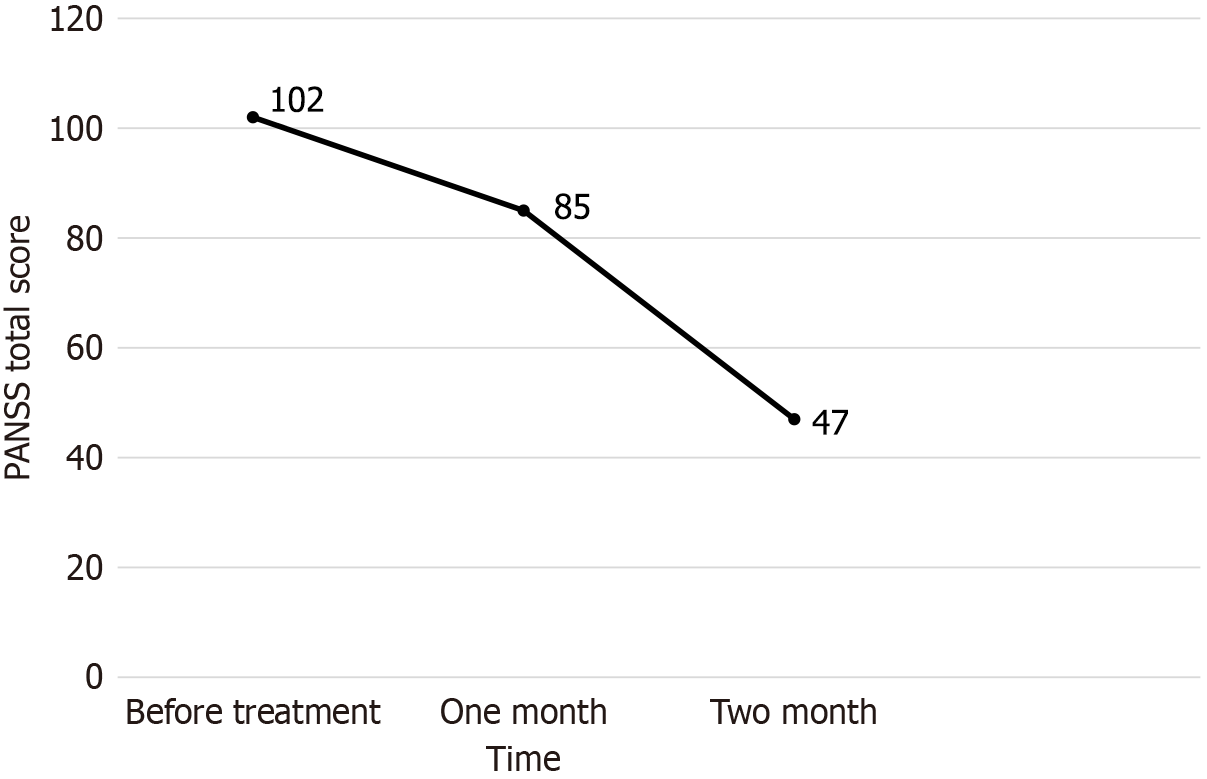

She was given 6 mg paliperidone extended-release tablets and 200 mg quetiapine extended-release tablets daily for approximately 4 weeks. She still heard voices, felt insecure, sometimes lost her temper and gestured with her hands. Her mother was very worried and anxious that her daughter would not be cured, and asked for better treatment. The patient’s condition was reassessed, and her treatment programme was readjusted. Quetiapine was stopped and changed to clozapine in combination with MECT. MECT was applied to the patient by using the Thymatron (Somatics, United States). She was fasted for at least 8 hours, and her vital signs were measured and bladder was emptied before MECT. Prior to MECT, succinylcholine chloride (20 mg) was used as a muscle relaxant, atropine (0.5 mg) was administered to reduce airway secretions, and etomidate (12 mg) was given to maintain anesthesia. Antipsychotic medications were discontinued during each treatment session. The electrodes were placed on her both temporal lobes. An initial electrical dose was based on 2/3 of the patients’ age and subsequent dosing was adjusted according to her physique, and seizure responsiveness. The patient underwent six sessions of MECT in 2 weeks, and clozapine was increased to 150 mg per day. The treatment course is shown in Tables 1 and 2. We used the positive and negative syndrome scale[22] to assess her psychiatric symptoms. Her symptoms markedly improved (Figure 1), and she was successfully discharged after 56 days of hospitalization.

| Time | Quetiapine extended-release tablets | Paliperidone extended-release tablets | Clozapine |

| March 4, 2024-March 5, 2024 | 50 mg/day | - | - |

| March 6, 2024-March 7, 2024 | 100 mg/day | - | - |

| March 8, 2024-March 10, 2024 | 150 mg/day | - | - |

| March 11, 2024-April 3, 2024 | 200 mg/day | - | - |

| March 9, 2024-March 14, 2024 | - | 3 mg/day | - |

| March 15, 2024-April 29, 2024 | - | 6 mg/day | - |

| April 4, 2024-April 5, 2024 | - | - | 25 mg/day |

| April 6, 2024-April 7, 2024 | - | - | 50 mg/day |

| April 8, 2024-April 11, 2024 | - | - | 100 mg/day |

| April 12, 2024-April 29, 2024 | - | - | 150 mg/day |

| Time | MECT |

| April 2, 2024 | First time |

| April 3, 2024 | Second time |

| April 6, 2024 | Third time |

| April 9, 2024 | Fourth time |

| April 13, 2024 | Fifth time |

| April 16, 2024 | Sixth time |

During half a year of outpatient follow-up, her condition have been stable, and she has been able to take care of herself.

This case report describes the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia in a patient who had been deaf since childhood. Diagnosis and treatment of such patients is challenging for psychiatrists because of communication barriers.

Making a definitive psychiatric diagnosis is highly difficult for people with deafness. To make a clear diagnosis of our patient, we took a detailed history from her parents and closely observed her behavior. Through sign language and written language, we conducted a detailed psychiatric examination of the patient. She experienced AVHs, a core symptom of schizophrenia[11]. She heard a male voice commanding her to die. She also experienced delusional symptoms and believed that her parents were aliens. She thought that there was too much electricity on Earth and that it was unsafe. She sometimes made noises, laughed to herself and made odd gestures. Because she was unable to communicate orally, we encountered difficulties in examining her thought disorder. In written communication, her written sentences contained logical errors and confusing concepts, such as “I’m an alien, a man, and I’m going to die”. Her social functioning and ability to work were impaired, and she had no self-awareness. The duration of the disease was 3 months. Apart from deafness, we found no other significant abnormalities in laboratory and imaging examinations. According to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision-10 system, her presentation was consistent with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Language disorders have long been recognized as a major identifying feature of schizophrenia. People with schizophrenia have language-processing deficits in many aspects. Deaf people often use sign languages as their principal means of communication. To communicate well with deaf patients, psychiatrists must learn some sign language. Psychiatrists should have patience to cultivate a good doctor-patient relationship and carefully observe patients’ various manifestations. Psychiatrists should repeatedly confirm their symptoms and make a clear diagnosis to provide proper treatment.

Our patient had significant psychiatric symptoms and emotional instability. After administration of quetiapine extended-release tablets at 200 mg/day, her symptoms did not substantially improve, and she still showed abnormal behavior, sometimes including shouting. After addition of paliperidone extended-release tablets at 6 mg/day, she still experienced AVHs and poor concentration. She had been hospitalized for more than 1 month, and her mother was very worried that her daughter would not be cured and requested adjustment of the treatment programme.

Through discussions with our supervising physician, we developed a new treatment strategy including MECT to relieve her psychiatric symptom. We discussed the advantages and possible adverse effects of this treatment with the patient’s mother and asked her to communicate with her daughter about the treatment. The patient and her mother agreed to the treatment and signed an informed consent form. Quetiapine extended-release tablets were discontinued, and clozapine tablets were gradually increased to 150 mg/day to treat the patient’s psychiatric symptoms. After 6 sessions of MECT over 2 weeks, the patient’s psychiatric symptoms of hallucinations and bizarre behavior were markedly alleviated.

She was emotionally stable and able to express herself through sign language and written language. After 56 days of hospitalization, she was discharged. At discharge, she was taking paliperidone extended-release tablets at 6 mg/d and clozapine orally disintegrating tablets at 150 mg/day. She has been visiting our hospital for regular follow-ups for 6 months and remains in stable condition. Treatment of psychiatric patients is more challenging in patients with deafness than those with normal hearing, because of the inability to communicate through spoken language[23]. Psychiatrists communicated with our patient in writing during daily rounds to better understand her thoughts and the efficacy of the medication. The nurses and her mother recorded her daily performance, emotional responses and behavioral changes. If poor outcomes were observed, the treatment plan was adjusted in a timely manner. MECT was found to be safe for our deaf patient and, in combination with antipsychotic medication, relieved her psychiatric symptoms.

Our deaf patient, who exhibited the same verbal hallucinations, delusions and behavioral abnormalities observed in people with schizophrenia with normal hearing, was diagnosed with schizophrenia. During the course of treatment, after drug treatment had been administered for a sufficient period and was found to be ineffective, MECT was promptly administered, and her psychiatric symptoms were controlled. Her condition remained stable during 6 months of follow-up after discharge. To make proper diagnoses and provide appropriate treatment for similar patients, psychiatrists must have patience and make efforts to better understand the patient’s mental state.

We express our gratitude to the patient and her parents, whose co-operation and consent were essential for the documen

| 1. | Zhang YM, Wang G. A comparative study of goji berry and ashwagandha extracts effects on promoting neural stem cell proliferation and reducing neuronal cell death. Food Med Homol. 2025;2:9420039. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Ye X, Tian WJ, Wang GH, Lin K, Zhu SX, Xia YY, Sun BL, Shu XJ, Liu W, Chen HF. The food and medicine homologous Chinese Medicine from Leguminosae species: A comprehensive review on bioactive constituents with neuroprotective effects on nervous system. Food Med Homol. 2025;2:9420033. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Dean B. Is schizophrenia the price of human central nervous system complexity? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43:13-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Atkinson JR. The perceptual characteristics of voice-hallucinations in deaf people: insights into the nature of subvocal thought and sensory feedback loops. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:701-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mitropoulos GB. Auditory Verbal Hallucinations in Psychosis: Abnormal Perceptions or Symptoms of Disordered Thought? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208:81-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Linszen MMJ, van Zanten GA, Teunisse RJ, Brouwer RM, Scheltens P, Sommer IE. Auditory hallucinations in adults with hearing impairment: a large prevalence study. Psychol Med. 2019;49:132-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schonauer K, Achtergarde D, Gotthardt U, Folkerts HW. Hallucinatory modalities in prelingually deaf schizophrenic patients: a retrospective analysis of 67 cases. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;98:377-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schonauer K, Achtergarde D, Suslow T, Michael N. Comorbidity of schizophrenia and prelingual deafness: its impact on social network structures. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:526-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schonauer K, Achtergarde D, Hornung WP. [Schizophrenic prelingual deaf and hearing patients. A comparison of premorbid and current data after several years of progression]. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 1998;66:170-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mehta DD, Siddiqui S, Ward HB, Steele VR, Pearlson GD, George TP. Functional and structural effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for the treatment of auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia: A systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2024;267:86-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sinclair DJ, Zhao S, Qi F, Nyakyoma K, Kwong JS, Adams CE. Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3:CD011847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zheng W, Cao XL, Ungvari GS, Xiang YQ, Guo T, Liu ZR, Wang YY, Forester BP, Seiner SJ, Xiang YT. Electroconvulsive Therapy Added to Non-Clozapine Antipsychotic Medication for Treatment Resistant Schizophrenia: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Espinoza RT, Kellner CH. Electroconvulsive Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:667-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 54.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Identifying and assessing psychosis in deaf psychiatric patients. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13:198-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Denmark JC. Mental illness and early profound deafness. Br J Med Psychol. 1966;39:117-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Matsumoto Y, Ayani N, Kitabayashi Y, Narumoto J. Longitudinal Course of Illness in Congenitally Deaf Patient with Auditory Verbal Hallucination. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2022;2022:7426850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Glickman N. Do you hear voices? Problems in assessment of mental status in deaf persons with severe language deprivation. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2007;12:127-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | du Feu M, McKenna PJ. Prelingually profoundly deaf schizophrenic patients who hear voices: a phenomenological analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;99:453-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Atkinson JR, Gleeson K, Cromwell J, O'Rourke S. Exploring the perceptual characteristics of voice-hallucinations in deaf people. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2007;12:339-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Landsberger SA, Diaz DR. Inpatient psychiatric treatment of deaf adults: demographic and diagnostic comparisons with hearing inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:196-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang J, Tang Y, Curtin A, Xia M, Tang X, Zhao Y, Li Y, Qian Z, Sheng J, Zhang T, Jia Y, Li C, Wang J. ECT-induced brain plasticity correlates with positive symptom improvement in schizophrenia by voxel-based morphometry analysis of grey matter. Brain Stimul. 2019;12:319-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13937] [Cited by in RCA: 15641] [Article Influence: 411.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Saha R, Sharma A, Srivastava MK. "Psychiatric assessment of deaf and mute patients - A case series". Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;25:31-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |