Published online May 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i5.104766

Revised: February 27, 2025

Accepted: March 14, 2025

Published online: May 19, 2025

Processing time: 120 Days and 6.2 Hours

Diabetes is becoming increasingly common and has become an important global health issue. In addition to physical damage, diabetes often leads to psychological complications, such as depressive symptoms. Self-care is considered to be the cornerstone of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) management. This research evaluated depression and explored the associations between self-care activities, self-perceived burden, and depression among T2DM patients in China.

To investigate the self-care activities and the association between depression and self-perceived burden among Chinese inpatients with T2DM.

A cross-sectional study was conducted in participants with T2DM. The data collected encompassed basic characteristics, diabetes self-care activities, depre

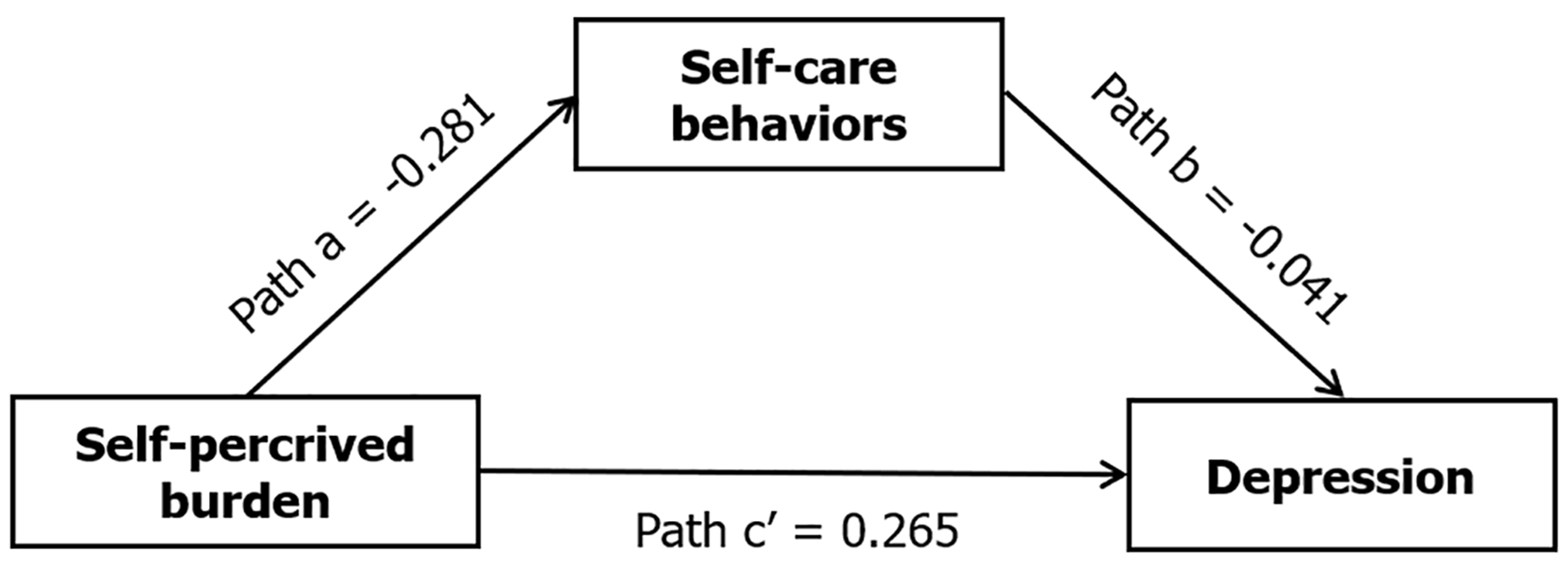

There were 599 T2DM patients in the survey, and 71.8% had been diagnosed with the disease for 1–10 years. There were significant correlations between self-care activities, depression, and self-perceived burden. The significant coefficients for paths a (B = -0.281, P < 0.001) and b (B = -0.041, P < 0.05) suggested negative associations between self-perceived burden and self-care behavior and between self-care activities and depression. The indirect effect (path a × b) of self-perceived burden on depression through self-care behaviors was significant (B = 0.020, P < 0.05), with a 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval of 0.007–0.036.

The mediating model presented here highlights the role of self-care activities in exerting both direct and indirect effects on depression in participants with T2DM.

Core Tip: The research evaluated depression status and explored the associations between self-care activities, self-perceived burden, and depression among type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients in China. The findings indicated that self-care activities had a partial mediating effect between depression and self-perceived burden. The results emphasize the multi

- Citation: Zhang R, Wang MY, Zhang XQ, Gong YW, Guo YF, Shen JH. Self-care activities mediate self-perceived burden and depression in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(5): 104766

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i5/104766.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i5.104766

Diabetes mellitus, characterized by elevated blood glucose concentrations due to abnormal cell biology on insulin activity, is a significant global health concern and a leading cause of disability and mortality worldwide[1]. Diabetes is becoming increasingly prevalent. According to the International Diabetes Federation estimation, the prevalence of diabetes was 10.5% in 2021, which will increase to 11.3% by 2030 and 12.2% by 2040, China has the largest number of diabetes patients, with 156 million , of which 90%–95% have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)[2]. Global diabetes-related healthcare expenditure is currently estimated to be at least US$966 billion and is projected to exceed US$1054 billion by 2045[3]. The expenses related to treating diabetes and complications in China rank second in the world, making diabetes management a public health priority in China, emphasizing the need for targeted efforts to prevent long-term complications[4].

It is worth noting that T2DM is the main cause of death and disability worldwide, and most diabetes-related deaths (> 80%) occur in low- and middle-income countries[5]. Psychological disorders, as one of the diabetic complications are usually neglected by patients and their families[6]. T2DM is associated with significant mental health burdens, including depression and anxiety; both of which are prevalent in individuals with it[7]. The proportion of T2DM patients with major depressive disorder was 30%, while that with generalized anxiety disorder was 50%[7]. A study of 276 people with T2DM in China found that respondents had poor knowledge of diabetes and that those using insulin had poor knowledge of its use[8]. In Chinese adults aged ≥ 65 years, the control, prevalence, and awareness rates of T2DM were 41.33%, 18.80%, and 77.14%, respectively. Therefore, effective measures to raise awareness and control the diabetes rate should be adopted to circumvent the growing disease burden on the Chinese population[9]. T2DM is associated with lifestyle and the knowledge possessed by those who are at a high risk of developing the disease[10].

Effectively improving self-management behavior and controlling negative mood in patients with T2DM are the key clinical goals in China. Motivation to perform it is important for these patients to achieve optimal glycemic control. A previous systematic review showed that psychological treatments cannot improve glycated hemoglobin levels in adults with T2DM[11]. Another systematic review and meta-analysis showed that physical activity improved depressive symptoms in managing comorbid depression in adults with T2DM[11]. In the general population, consistent reports in the relevant literature have underlined the antidepressant efficacy of physical activities[12].

Self-care is essential to successful disease management among T2DM patients, who need long-term dietary control, strict medication adherence, and continuous blood sugar monitoring to control symptoms, prevent complications, and improve outcomes[13]. Some studies have explored the mediating role of depression in the relationship between diabetes management self-efficacy and self-care activities among older Chinese adults with T2DM[14]. However, no study has explored whether self-care activities mediate the relationship between self-perceived burden and depression. Therefore, the potential mechanisms between self-care activities and the self-perceived burden of depression are worth investigating. We hypothesize that negative emotions, such as depression, directly affect self-perceived burden and that self-care activities play a mediating role between negative emotions and self-perceived burden.

An online questionnaire was distributed to patients with T2DM at the hospital of Changde (Hunan Province, China) between June 15 and July 15, 2023. Data were collected using the online crowdsourcing platform, Wenjuanxing (www.wjx.cn). The questionnaire includes an informed consent form. A convenience sampling method was used to for this cross-sectional study recruit T2DM patients with the following inclusion criteria: (1) Diagnosed with T2DM; (2) Aged ≥ 18 years; and (3) Ability to communicate with normal cognitive and mental function. The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients with T2DM who had a disability and inpatients with T2DM who had impaired consciousness or communication skills, especially when using smartphones. At the beginning of the questionnaire, preliminary remarks clarified the theme of this research, and provided informed consent guidelines. Those who agreed to complete the survey chose “yes”, indicating informed consent and participation in the investigation. Individuals who chose “no” were not provided access to the web questionnaire. Only participants who chose “yes” were given access, otherwise, the survey will be terminated.

The sample size of this study was calculated from equation 1[15]: n = (Zα/2)2 P (1 - p) 2/d2. The value of Zα/2 represented 1.96, In our research, the rate of depression followed that of reference[16], the prevalence of T2DM was 16.9%, and d was the desired deviation (equation 2): d = 0.05 (d2 = 0.05 × 0.05). Thus, the sample size was n = 1.962 × 0.169 × (1 -0.169)/

The questionnaire included four components, namely, the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with T2DM, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) questionnaire, and Self-Perceived Burden Scale (SPBS).

The sociodemographic component of the questionnaire was designed in accordance with the study’s purpose and content, and it included demographic and sociological data such as age, marital status, education, sex, occupation, income, lifestyles and customs.

PHQ-9 is designed to assess the symptoms of depression and diagnose depressive disorders, and the total score ranges from 0 to 27[17]. According to the total score, the severity of symptoms can be divided into five grades, normal (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19), and severe (≥ 20)[18]. Cronbach’s α for the Chinese version of PHQ-9 was 0.87[19]. Cronbach’s α for the PHQ-9 of the research was 0.86. If the ninth question (about suicide/self-harm) was answered “yes”, we intervened accordingly. Specific measures included immediately contacting the patient's attending physician and recommending further psychological assessment and intervention. For patients with severe suicidal or self-harm tendencies, we also helped them with referral to professional mental health institutions. Details of the scale are detailed in the Supplementary material.

The SDSCA scale was used to measure adherence to self-care activities undertaken by patients with T2DM. The original SDSCA method was developed by reference[20]. The Chinese version of the SDSCA measure was edited and evaluated by reference[21], including 11 items under five dimensions: Blood glucose monitoring, diet, foot care, compliance with medication, and exercise, and each item is rated on an eight-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 7[22]. The Chinese version addresses diet, exercise, blood glucose monitoring, footcare, compliance with medication, and smoking; these six dimensions (11 items) showed high reliability and validity. Cronbach’s α was 0.913, the test–retest reliability coefficient was 0.774 (P < 0.01)[23]. In our study, the total Cronbach’s α of the SDSCA was 0.706, and Cronbach’s α for each di

In 2003, SPBS was first designed and developed by reference[24]. In the Chinese version, the scale contains 10 items across three dimensions. The total score is between 10 and 50 points[25]. The results can be divided into four grades, normal, mild, moderate, and severe self-perceived burden (10-20, 20-30, 30-40, and ≥ 40)[26]. Cronbach’s α for the Chinese version was 0.91[25]; Cronbach’s α of this research was 0.85. Details of the scale are shown in the Supplementary material.

SPSS 26.0 and the PROCESS macro program were used for statistical analysis. Data were expressed as mean ± SD, frequency, and percentage. Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed, and the PROCESS macro program and IBM Bootstrapping method (SPSS 26.0) were applied to test the mediating effect of self-care behavior between self-perceived burden and depression. The number of samples was set to 5000, and the confidence interval to 95%.

The geometric age of the 599 patients was 57.98 years (95% confidence interval: 56.83–59.15 years), and 313 (52.3%) were men. Most patients were married (90.3%); 119 (19.9%) drank alcohol, and 141 (23.5%) smoked. The patients’ mean self-care behavior score was 43.78. Furthermore, 19 patients (3.17%) reported a high self-perceived burden, and nearly half had depression (42.1%) (Table 1).

| Variable | Mean (SD)/median (IQR) | Geo mean (95%CI) | n (%) |

| Age (yr) | 59.60 (12.68) | 57.98 (56.83-59.15) | - |

| Gender | - | - | - |

| Male | - | - | 313 (52.3) |

| Female | - | - | 286 (47.7) |

| Marriage | |||

| Married | - | - | 541 (90.3) |

| Unmarried | - | - | 58 (9.7) |

| Education | - | - | - |

| Junior college or below | - | - | 536 (89.5) |

| College or above | - | - | 63 (10.5) |

| Diabetes duration (yr) | 7.00 (1.00-12.00) | 4.46 (4.00-4.97) | - |

| 1-10 | - | - | 430 (71.8) |

| > 10 | - | - | 69 (28.2) |

| Do you drink alcohol? | - | - | - |

| Yes | - | - | 119 (19.9) |

| No | - | - | 480 (80.1) |

| Do you smoke? | - | - | - |

| Yes | - | - | 141 (23.5) |

| No | - | - | 458 (76.5) |

| Self-care behavior (SDSCA total) | 43.78 (15.66) | 40.42 (39.04-41.85) | - |

| Diet | 18.85 (5.59) | 17.81 (17.29-18.34) | - |

| Exercise | 6.53 (4.31) | 6.42 (6.08-6.77) | - |

| Blood sugar testing | 5.94 (5.08) | 6.06 (5.65-6.50) | - |

| Foot care | 7.21 (5.63) | 8.37 (7.89-8.88) | - |

| Taking medication | 5.25 (2.64) | 5.80 (5.60-6.01) | - |

| Self-perceived burden | 19.12 (9.34) | 17.23 (16.63-17.85) | 19 (3.17) |

| Depression | 4.98 (5.31) | 4.77 (4.40-5.17) | - |

| Depressed | - | - | 252 (42.1) |

| Not depressed | - | - | 347 (57.9) |

Table 2 shows correlations between self-care behavior, depression, and self-perceived burden. Depression (r = 0.485, P < 0.01) was positively correlated with self-perceived burden, whereas depression (r = -0.197, P < 0.01) and self-perceived burden (r = -0.168, P < 0.01) were negatively correlated with self-care behavior. Table 3 presents the results of mediation analyses. The effect (path c) of self-perceived burden on depression was significant (B = 0.276, P < 0.001). The significant coefficients of paths a (B= -0.281, P < 0.001) and b (B = -0.041, P < 0.001) indicated negative associations between self-perceived burden on self-care behavior and self-care behavior on depression. The indirect effect (path a × b) between self-perceived burden and depression through self-care behavior was significant (B = 0.020, P < 0.05), and the 95% bias-corrected Bootstrap confidence interval was 0.007–0.036. Path c was significant (B = 0.265, P < 0.001), indicating that self-care behavior partially mediated the relationship between self-perceived burden and depression. Figure 1 shows the significant coefficients.

The study assessed the status of depression among patients with T2DM and explored the mediating role of self-care activities on self-perceived burden and depression. As previously stated, this study included 599 patients with T2DM. The findings indicated that self-perceived burden, depression, and self-care activities were closely related and that self-care activities had a partial mediating effect between depression and self-perceived burden.

T2DM is a significant clinical and public health problem[27], and poor mental health is frequently observed in patients with T2DM. Approximately one in four patients with T2DM has clinically significant depression[28]. Furthermore, T2DM increases the risk of depression, which, in turn, increases the risk of hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, consequently worsening T2DM[28]. Patients with T2DM and depression have a higher risk of complications, such as poor adherence, poor quality of life, dementia, and cardiovascular events, than those without diabetes[29-34]. Therefore, reducing the incidence of depression improves healing and reduces patient burden, which is critical for patients with T2DM[35].

In this study, in T2DM patients, the prevalence of depression was 42.1%. Previous studies have shown that 28% of T2DM patients have varying degrees of depression[36], and prevalence of major depressive disorder is 14.5%[37]. Some studies have shown that the prevalence of depression in T2DM patients ranges from 34% to 54%[38-40]. This may be related to cultural differences and varied social support systems. It may also be that the patients have a long disease course, many complications, and a high risk of complications. The corresponding types of medication also increase, heightening the patient’s economic burden and psychological pressure.

SPBS is an important psychological tool for assessing mental health, anxiety, depression, frustration, and other negative emotions. The scores indicate whether patients have lost confidence in their treatment, which can seriously impair quality of life. Diabetes treatment is a lengthy process, and with prolonged treatment and strict management, many patients find it difficult to perceive its effects. In some patients, disease complications and adverse reactions to drugs contribute to a decline in treatment compliance and aggravate self-perceived burden.

Individuals with diabetes tend to experience a greater burden of psychosocial problems[41]. In the present study, the mediating role of self-care activities confirmed our hypothesis that self-care activities mediated depression and self-perceived burden in patients with T2DM. Diabetes self-care activities include exercise, smoking, diet, blood glucose testing, and medication[42]. Among these, physical activity has long been considered as the primary treatment for T2DM[43]. Previous studies have found that moderate exercise promotes blood circulation, burns more energy, accelerates glucose catabolism, and reduces glucose levels; the muscle uptake of glucose gradually increases with longer exercise time[44-46]. Self-care activities reduce depression by improving the symptoms of patients with diabetes and lowering their self-perceived burden[47,48]. Additionally, an appropriate diet can improve depressive symptoms and T2DM[49]. Self-care activities, including diet control, blood glucose management, regular exercise and drug compliance, have been shown to significantly improve depressive symptoms in diabetic patients in several clinical and epidemiological studies. For example, a cross-sectional study of people with T2DM found that adherence to a healthy diet was significantly associated with a lower risk of depression[48]. As an important part of self-care activities, diet management can improve the physiological indicators of diabetic patients and have a positive impact on mental health by regulating the gut microbiota and neuroendocrine function[50].

The findings of this study suggest that the effects of self-care activities (especially exercise) on diabetes-related de

The main advantage of this study was the use of established research processes and psychometric evaluation procedures. However, this study had several limitations. First, we did not separately analyze the mediating role of specific dimensions of self-care (such as diet, exercise, and blood glucose monitoring), which may affect our in-depth understanding of the mechanisms of self-care activities. Second, the study used a cross-sectional design, so it was impossible to determine the causal relationship between variables. In the future, longitudinal studies can be used to verify the mediating role of self-care behavior between self-perceived burden and depression. Finally, the single-center surveys and small sample size may limit the universality of our results. Large multicenter studies are needed to verify these results in different populations.

This study used a mediating model to show that self-perceived burden had both direct and indirect effects on depression in people with T2DM through self-care activities, such as exercise and diet. Further studies are warranted to validate these results in a larger multicenter cohort; develop more effective prevention, early intervention, and personalized care strategies; integrate self-care methods into the management of patients with T2DM; and ultimately improve the quality of life and prognosis of patients with T2DM.

| 1. | Chatterjee S, Khunti K, Davies MJ. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2017;389:2239-2251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1234] [Cited by in RCA: 1654] [Article Influence: 206.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, Pavkov ME, Ramachandaran A, Wild SH, James S, Herman WH, Zhang P, Bommer C, Kuo S, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3033] [Cited by in RCA: 4316] [Article Influence: 1438.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 3. | GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2023;402:203-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1683] [Cited by in RCA: 1458] [Article Influence: 729.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu X, Zhang L, Chen W. Trends in economic burden of type 2 diabetes in China: Based on longitudinal claim data. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1062903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Taborda Restrepo PA, Acosta-Reyes J, Estupiñan-Bohorquez A, Barrios-Mercado MA, Correa Gonzalez NF, Taborda Restrepo A, Barengo NC, Gabriel R. Comparative Analysis of Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Latin America. Curr Diab Rep. 2023;23:89-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Guo J, Whittemore R, Jeon S, Grey M, Zhou ZG, He GP, Luo ZQ. Diabetes self-management, depressive symptoms, metabolic control and satisfaction with quality of life over time in Chinese youth with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:1258-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McInerney AM, Lindekilde N, Nouwen A, Schmitz N, Deschênes SS. Diabetes Distress, Depressive Symptoms, and Anxiety Symptoms in People With Type 2 Diabetes: A Network Analysis Approach to Understanding Comorbidity. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:1715-1723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Phoosuwan N, Ongarj P, Hjelm K. Knowledge on diabetes and its related factors among the people with type 2 diabetes in Thailand: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:2365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yan Y, Wu T, Zhang M, Li C, Liu Q, Li F. Prevalence, awareness and control of type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk factors in Chinese elderly population. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sami W, Ansari T, Butt NS, Hamid MRA. Effect of diet on type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2017;11:65-71. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Winkley K, Upsher R, Stahl D, Pollard D, Kasera A, Brennan A, Heller S, Ismail K. Psychological interventions to improve self-management of type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24:1-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Arsh A, Afaq S, Carswell C, Bhatti MM, Ullah I, Siddiqi N. Effectiveness of physical activity in managing co-morbid depression in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;329:448-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Oluma A, Mosisa G, Abadiga M, Tsegaye R, Habte A, Abdissa E. Predictors of Adherence to Self-Care Behavior Among Patients with Diabetes at Public Hospitals in West Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:3277-3288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jiang R, Ta X, Xu M, Luo Z, Du Y, Zhong X, Pan T, Cao X. Mediating Role of Depression Between Diabetes Management Self-Efficacy and Diabetes Self-Care Behavior Among Elderly Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in China. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:1545-1555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tesfaye Y, Agenagnew L, Anand S, Tucho GT, Birhanu Z, Ahmed G, Getnet M, Yitbarek K. Knowledge of the community regarding mental health problems: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. 2021;9:106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dinh Le T, Huy Duong H, Thi Nguyen L, Phi Thi Nguyen N, Tien Nguyen S, Van Ngo M. The Relationship Between Depression and Multifactorial Control and Microvascular Complications in Vietnamese with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Aged 30-60 Years. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2022;15:1185-1195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sun XY, Li YX, Yu CQ, Li LM. [Reliability and validity of depression scales of Chinese version: a systematic review]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2017;38:110-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brähler E. Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:551-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 39.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li J, Liu C, Wulandari T, Wang P, Li K, Ren L, Liu X. The relationship between dimensions of empathy and symptoms of depression among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A network analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1034119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:943-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1481] [Cited by in RCA: 1669] [Article Influence: 66.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Song X, Chen L, Zhang T, Xiang Y, Yang X, Qiu X, Qiao Z, Yang Y, Pan H. Negative emotions, self-care activities on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Health Med. 2021;26:499-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lin K, Yang X, Yin G, Lin S. Diabetes Self-Care Activities and Health-Related Quality-of-Life of individuals with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Shantou, China. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:147-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zheng F, Liu S, Liu Y, Deng L. Effects of an Outpatient Diabetes Self-Management Education on Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in China: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Diabetes Res. 2019;2019:1073131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cousineau N, McDowell I, Hotz S, Hébert P. Measuring chronic patients' feelings of being a burden to their caregivers: development and preliminary validation of a scale. Med Care. 2003;41:110-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tang B, Fu Y, Liu B, Yi Q. Self-perceived burden and associated factors in Chinese adult epilepsy patients: A cross-sectional study. Front Neurol. 2022;13:994664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chen Y, Wei Y, Lang H, Xiao T, Hua Y, Li L, Wang J, Guo H, Ni C. Effects of a Goal-Oriented Intervention on Self-Management Behaviors and Self-Perceived Burden After Acute Stroke: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Neurol. 2021;12:650138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Taylor L. Diabetes prevalence in Americas tripled in 30 years. BMJ. 2022;379:o2868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Semenkovich K, Brown ME, Svrakic DM, Lustman PJ. Depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus: prevalence, impact, and treatment. Drugs. 2015;75:577-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, Collins EM, Serpa L, Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2398-2403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 627] [Cited by in RCA: 685] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Jing X, Chen J, Dong Y, Han D, Zhao H, Wang X, Gao F, Li C, Cui Z, Liu Y, Ma J. Related factors of quality of life of type 2 diabetes patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16:189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Katon W, Pedersen HS, Ribe AR, Fenger-Grøn M, Davydow D, Waldorff FB, Vestergaard M. Effect of depression and diabetes mellitus on the risk for dementia: a national population-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:612-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Farooqi A, Khunti K, Abner S, Gillies C, Morriss R, Seidu S. Comorbid depression and risk of cardiac events and cardiac mortality in people with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;156:107816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hazuda HP, Gaussoin SA, Wing RR, Yanovski SZ, Johnson KC, Coday M, Wadden TA, Horton ES, Van Dorsten B, Knowler WC; Look AHEAD Research Group. Long-term Association of Depression Symptoms and Antidepressant Medication Use With Incident Cardiovascular Events in the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) Clinical Trial of Weight Loss in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:910-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chen Y, Long C, Xing Z. Depression is associated with heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1181336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Jing Z, Chu J, Imam Syeda Z, Zhang X, Xu Q, Sun L, Zhou C. Catastrophic health expenditure among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A province-wide study in Shandong, China. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10:283-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Khaledi M, Haghighatdoost F, Feizi A, Aminorroaya A. The prevalence of comorbid depression in patients with type 2 diabetes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis on huge number of observational studies. Acta Diabetol. 2019;56:631-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 31.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wang F, Wang S, Zong QQ, Zhang Q, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, Xiang YT. Prevalence of comorbid major depressive disorder in Type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of comparative and epidemiological studies. Diabet Med. 2019;36:961-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Hussain S, Habib A, Singh A, Akhtar M, Najmi AK. Prevalence of depression among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in India: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:264-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Pashaki MS, Mezel JA, Mokhtari Z, Gheshlagh RG, Hesabi PS, Nematifard T, Khaki S. The prevalence of comorbid depression in patients with diabetes: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13:3113-3119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Roy T, Lloyd CE, Parvin M, Mohiuddin KG, Rahman M. Prevalence of co-morbid depression in out-patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Bangladesh. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gonzalez JS, Esbitt SA, Schneider HE, Osborne PJ, Kupperman EG. Psychological Issues in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. In: Pagoto S, editor. Psychological Co-morbidities of Physical Illness. New York: Springer, 2011: 73-121. |

| 42. | Williams JS, Walker RJ, Smalls BL, Hill R, Egede LE. Patient-Centered Care, Glycemic Control, Diabetes Self-Care, and Quality of Life in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18:644-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Olson EA, Mullen SP, Raine LB, Kramer AF, Hillman CH, McAuley E. Integrated Social- and Neurocognitive Model of Physical Activity Behavior in Older Adults with Metabolic Disease. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51:272-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | van Dam RM. The epidemiology of lifestyle and risk for type 2 diabetes. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18:1115-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Umpierre D, Ribeiro PA, Kramer CK, Leitão CB, Zucatti AT, Azevedo MJ, Gross JL, Ribeiro JP, Schaan BD. Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:1790-1799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 813] [Cited by in RCA: 844] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Wasserman DH, Castaneda-Sceppa C, White RD. Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes: a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1433-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 632] [Cited by in RCA: 582] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kato A, Fujimaki Y, Fujimori S, Isogawa A, Onishi Y, Suzuki R, Yamauchi T, Ueki K, Kadowaki T, Hashimoto H. Association between self-stigma and self-care behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2016;4:e000156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kurdi SM, Alamer A, Albaggal A, Alsuwaiket M, Alotaibi FM, Asiri IM, Alshayban DM, Alsultan MM, Alshehail B, Almalki BA, Hussein D, Alotaibi MM, Alfayez OM. The Association between Self-Care Activities and Depression in Adult Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey Study. J Clin Med. 2024;13:419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Duc HN, Oh H, Yoon IM, Kim MS. Association between levels of thiamine intake, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and depression in Korea: a national cross-sectional study. J Nutr Sci. 2021;10:e31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Mariño E, Richards JL, McLeod KH, Stanley D, Yap YA, Knight J, McKenzie C, Kranich J, Oliveira AC, Rossello FJ, Krishnamurthy B, Nefzger CM, Macia L, Thorburn A, Baxter AG, Morahan G, Wong LH, Polo JM, Moore RJ, Lockett TJ, Clarke JM, Topping DL, Harrison LC, Mackay CR. Gut microbial metabolites limit the frequency of autoimmune T cells and protect against type 1 diabetes. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:552-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 504] [Article Influence: 63.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |