Published online Apr 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.104625

Revised: January 30, 2025

Accepted: February 21, 2025

Published online: April 19, 2025

Processing time: 89 Days and 20.5 Hours

Examining patterns of media consumption and their associations with mental health outcomes in the general population during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has implications for public mental health in future pan

To investigate patterns of media consumption and their associations with depressive and anxiety symptoms among adults affected by the COVID-19 pan

A total of 8473 adults were recruited through snowball sampling for an online cross-sectional survey. The participants were asked to report the three media sources from which they most frequently acquired knowledge about COVID-19 from a checklist of nine media sources. Depression and anxiety were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale, respectively. A two-step cluster analysis was performed to identify distinct clusters of consumption of media sources.

Seven clusters were identified. The lowest prevalence of depression and anxiety (29.1% and 22.8%, respectively) was observed in cluster one, which was labeled “television and news portals and clients, minimal social media”. The highest prevalence of depression (43.1%) was observed in cluster three, labeled “WeChat, MicroBlog, and news portals, minimal traditional media”. The greatest prevalence of anxiety (35.8%) was observed in cluster seven, which was labeled “news clients and WeChat, no newspaper, radio, or news portals”. Relative to cluster one, a significantly elevated risk of depression and anxiety was found in clusters three, six (labeled “news portals and clients, WeChat, no newspaper and radio”) and seven (adjusted odds ratio = 1.28-1.46, P ≤ 0.011). Multiple logistic regression analyses revealed that the risk of COVID-19 infection and knowledge about COVID-19 partially explained the variations in the prevalence of depression and anxiety across the seven clusters.

Communication policies should be designed to channel crucial pandemic-related information more effectively through traditional and digital media sources. Encouraging the use of these media and implementing regulatory policies to reduce misinformation and rumors on social media, may be effective in mitigating the risk of depression and anxiety among populations affected by the pandemic.

Core Tip: This study examined media consumption patterns and their relationships with depressive and anxiety symptoms among the general population during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. In the cluster analysis, survey participants’ media preferences were categorized into seven clusters. A higher risk of depression and anxiety was observed among participants who primarily consumed media through social platforms, with minimal engagement in traditional and digital media sources. Encouraging the use of traditional and digital media, along with implementing regulatory policies on social media platforms, has the potential to mitigate the risk of depression and anxiety in the general population during future medical pandemics.

- Citation: Wu RY, Ge LF, Zhong BL. Media consumption patterns and depressive and anxiety symptoms in the Chinese general population during the COVID-19 outbreak. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(4): 104625

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i4/104625.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.104625

Both traditional and social media platforms, play a vital role in the public health response to pandemics caused by emerging infectious diseases[1]. Disseminating authoritative health information through media increases public awareness of the risks posed by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and helps to reduce public fear during a pandemic. Furthermore, media foster public adherence to preventive behaviors, such as physical distancing and mask-wearing[2]. These platforms also enable health experts to share insights and progress, which contributes to an enhanced public understanding of the epidemic. Despite the beneficial effects of media, the accompanying “infodemic”, which is characterized by the rapid spread of an abundance of fear-based, false, or inaccurate information about the pandemic on media platforms - tends to amplify perceived risk and exacerbate mental health problems among the general public[3]. Numerous population-based studies have reported a positive association between media use and the risk of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic[1,2,4-6].

Prior studies have examined the relationship between mental health problems and media use with a focus on the duration of exposure, the content, and the source of the information. For example, two studies revealed a significant positive dose-response relationship between the daily frequency or duration of media exposure and the severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms in the general population in China and Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic[6,7]. Three studies conducted during the pandemic reported that exposure to rumors, misinformation, and negative pandemic-related information was significantly associated with an increased risk of mental health problems, including depressive and anxiety symptoms, stress, and social isolation[8-11]. Moreover, two studies reported that lower levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms were significantly associated with the use of the government’s WhatsApp messaging channel, viewing experts’ speeches, and reading about COVID-19 and its prevention[2,8]. With regard to the source of information, one recurring finding in past studies was that the use of social media - not traditional media - was significantly related to an increase in the risk of mental health problems[2,6,12,13].

Nonetheless, it remains challenging to determine the implications of the significant links between media sources and mental health problems when planning crisis mental health services during pandemics. This difficulty arises because most studies have categorized information sources into traditional vs social media, without providing detailed data on the subtypes of the media used, such as Twitter and newspapers. Generally, every individual has habitual preferences for media consumption to obtain COVID-19 information. Individuals are likely to uses multiple media sources, including both traditional and social media platforms. For example, an empirical survey of 1006 Chinese adults in March 2020 reported that 91.2%, 89%, 57.7%, and 35.5% obtained information about COVID-19 from WeChat, television, QQ, and newspapers, respectively. Given the very high percentages of consumption of these media sources, the percentage of individuals who consume two or more sources simultaneously should also be very high[14]. Therefore, data on the source-level relationship between media consumption patterns and mental health problems have public health implications. However, previous studies have rarely examined the combined effects of the use of multiple information sources on mental health. Given the variability in people’s media consumption preferences, it is necessary to revisit the relationship between patterns of media consumption and mental health problems within pandemic-affected populations.

Cluster analysis is a data-driven statistical method used to create “clusters”. Individuals within the same cluster are more similar to each other than to individuals in different clusters. This method helps to identify pertinent phenotypes of behaviors without the need for predefined categories or classes[15,16]. To bridge the aforementioned knowledge gap, this study employed cluster analysis to identify patterns of media use behaviors related to the acquisition of COVID-19 knowledge and analyzed their associations with depressive and anxiety symptoms in the general adult population during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. On the basis of these studies, we speculated that there would be variations in the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms across clusters characterized by different combinations of media sources. Because a high level of perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and a low level of knowledge about COVID-19 have been linked to depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and loneliness in populations affected by COVID-19[17-20], we also investigated risk perceptions and COVID-19 knowledge across the identified clusters, as well as their potential role in the unique risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms within each cluster. We hypothesized that clusters that exhibited more depressive and anxiety symptoms would perceive an elevated risk of COVID-19 infection and display poor knowledge about COVID-19.

The present study was a secondary analysis of data from a large-scale online cross-sectional survey conducted between January 27 and March 14, 2020, during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in China[21]. Since household-based random sampling was not feasible during the crisis period, we recruited participants online via the snowball sampling method. Briefly, a one-page recruitment poster that included information on the background of the study, anonymity, the confidentiality of the survey, and a link and quick response code for the questionnaire was posted/reposted on popular social media platforms such as WeChat and MicroBlog as well as on the official websites of Wuhan’s prominent traditional media outlets, such as Yangtze River Daily, Wuhan - Listen Online, and ChuTian Metropolis Daily. The snowball sampling of Chinese residents began with several individuals who were willing to participate in the questionnaire survey. After they completed the survey, they were asked to invite other individuals they knew personally to participate in the study. The participants were also encouraged to share the invitation poster on their social media platforms and in groups. Eligible participants were Chinese individuals aged 16 years and older with no confirmed or suspected diagnosis of COVID-19 who voluntarily completed the survey.

The Institutional Review Board of Wuhan Mental Health Center approved our study protocol and procedures of informed consent before the formal survey. Before the participants proceeded with the online self-administration of the questionnaire, they were required to answer a yes-no question to confirm their willingness to participate voluntarily.

The demographic variables in the questionnaire included sex, age, educational attainment, and marital status. To assess the objective risk of COVID-19 infection, respondents were asked if they had a family member or close relative infected with COVID-19 and if they had a colleague, friend, or classmate infected by the virus. To evaluate the perceived risk of COVID-19 infection, participants were asked whether they were concerned about contracting COVID-19 themselves and whether they were worried about their family members contracting it[20]. COVID-19 knowledge was assessed via the COVID-19 knowledge questionnaire developed by Ruan et al[20]. The total knowledge score ranged between zero and 12, with a score of eight or lower denoting poor COVID-19 knowledge in terms of the clinical characteristics, transmission routes, prevention strategies, and containment measures of COVID-19[20].

After the participants completed the COVID-19 knowledge questionnaire, they were asked to select the three media sources from which they most frequently acquired information about COVID-19. The response options included newspapers, television, radio, news portals, WeChat, QQ, MicroBlog, news clients, and others. These information sources can be broadly categorized into three subtypes according to the form of communication (i.e., print vs digital), the method of information distribution, and the involvement of interactive, user-generated content: Traditional media (including newspapers, television, and radio), digital media (such as news portals and news clients), and social media platforms (such as WeChat, QQ, and MicroBlog). Traditional media are characterized by one-way communication and limited user interaction, with information distributed through physical or broadcast channels. Compared with traditional media, digital media offer more interactivity but still primarily involve one-way communication. Social media empower users to both consume and create content and provide a highly interactive experience with information distribution that is often rapid and widespread. Depressive and anxiety symptoms were assessed with the validated Chinese versions of the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire and the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale, respectively. These two scales are widely used as self-administered tools to assess depressive and anxiety symptoms worldwide. The cut-off scores for the presence of depressive and anxiety symptoms were both set at five or higher[22,23].

Nine binary variables that represented media sources were used in the cluster analysis. A two-step cluster analysis was performed to identify distinct clusters using the log-likelihood as the distance measure. The optimal number of clusters was automatically determined by this statistical method. The percentages of media sources across clusters were compared using the χ2-test. To determine the independent relative risk of each cluster having depressive symptoms, a multiple logistic regression analysis was performed. This analysis considered the presence of depressive symptoms as the outcome, the cluster as the predictor, and demographic and infection-related variables as well as poor COVID-19 knowledge as covariates. The relative risk of anxiety symptoms for each cluster was analyzed in the same manner. All analyses were conducted using SPSS software for Windows, version 17.0 (SPSS Ltd.). A two-sided P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In total, 8473 participants provided complete questionnaire data. Among the sample, 3265 were men (38.5%) and the average age was 33.03 years with a standard deviation of 10.58. Table 1 displays the demographic details and infection-related characteristics of the study participants. A total of 492 participants (5.8%) were assessed as having poor knowledge of COVID-19. The three most commonly reported sources for COVID-19 information were WeChat (81.7%), television (63.9%), and news portals (61.5%).

| Variable | n | % |

| Sex | ||

| Males | 3265 | 38.5 |

| Females | 5208 | 61.5 |

| Age, years | 33.03 ± 10.58 | 16-90 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| College and above | 7043 | 83.1 |

| Senior middle school and below | 1430 | 16.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Currently married | 4812 | 56.8 |

| Others | 3661 | 43.2 |

| Family member or close relatives infected with COVID-19 | 102 | 1.2 |

| Colleagues, friends, or classmates infected with COVID-19 | 798 | 9.4 |

| Worry of COVID-19 infection | 6525 | 77.0 |

| Worry of family members’ COVID-19 infection | 7528 | 88.8 |

| Poor COVID-19 knowledge | 492 | 5.8 |

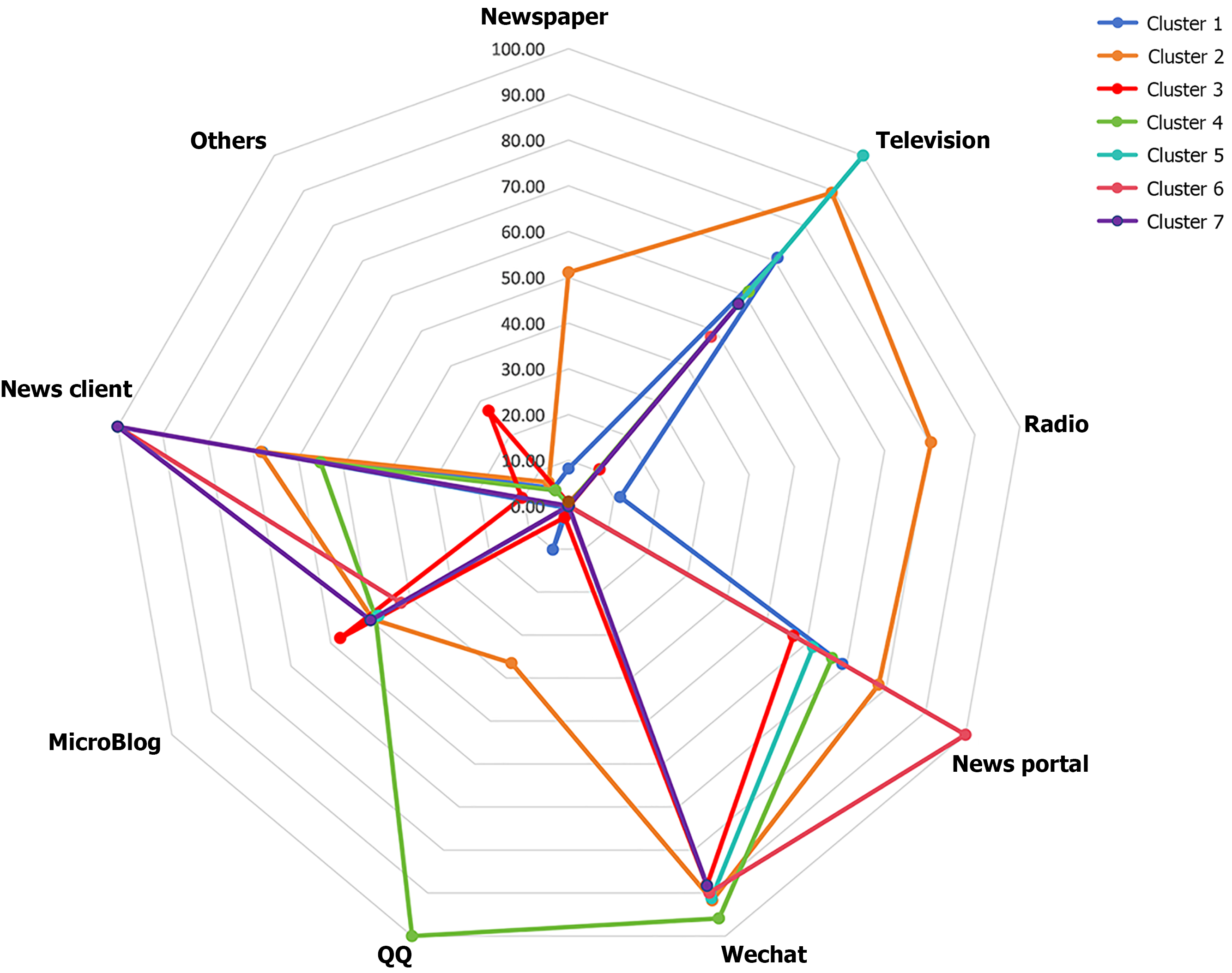

The cluster analysis identified seven clusters (Table 2, Figure 1). Cluster one, the smallest (n = 839), was characterized by high percentages of television (70.9%), news portals (69.0%), and news clients (67.9%), and low percentages of WeChat (0.0%) and MicroBlog (0.7%). Cluster two featured high percentages of television (89.4%), radio (80.3%), news portals (78.1%), and WeChat (91.7%). Cluster three was marked by low percentages of newspaper (0.6%) and radio (0.1%) but high percentages of WeChat (88.2%) and MicroBlog (57.6%). Cluster four included high percentages of television (61.2%), news portals (66.4%), WeChat (95.9%), and QQ (100%). Cluster five was defined by its high percentages of television (100%), news portals (61.6%), and WeChat (91.2%). Cluster six, the largest (n = 1587), was characterized by low percentages of newspaper (0.0%) and radio (0.0%) but high percentages of news portals (100%), WeChat (89.9%), and news clients (100%). Finally, Cluster seven presented low percentages of newspaper (0.0%), radio (0.0%), and news portals (0.0%) but high percentages of television (57.7%), WeChat (88.3%), and news clients (100.0%). The percentages of the nine media sources differed significantly across the seven clusters (P < 0.001).

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Cluster 7 | χ2 | P value | |

| Source | |||||||||

| Newspaper | 69 (8.2) | 618 (51.1) | 6 (0.6) | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3507.478 | < 0.001 |

| Television | 595 (70.9) | 1081 (89.4) | 106 (10.5) | 575 (61.2) | 1469 (100.0) | 766 (48.3) | 821 (57.7) | 2626.667 | < 0.001 |

| Radio | 96 (11.4) | 971 (80.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5956.988 | < 0.001 |

| News portal | 579 (69.0) | 944 (78.1) | 571 (56.7) | 624 (66.4) | 905 (61.6) | 1587 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3444.272 | < 0.001 |

| 0 (0.0) | 1109 (91.7) | 888 (88.2) | 901 (95.9) | 1339 (91.2) | 1426 (89.9) | 1256 (88.3) | 4174.147 | < 0.001 | |

| 85 (10.1) | 441 (36.5) | 26 (2.6) | 940 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5840.988 | < 0.001 | |

| MicroBlog | 6 (0.7) | 597 (49.4) | 580 (57.6) | 458 (48.7) | 704 (47.9) | 672 (42.3) | 709 (49.9) | 767.076 | < 0.001 |

| News client | 570 (67.9) | 825 (68.2) | 105 (10.4) | 517 (55.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1587 (100.0) | 1422 (100.0) | 5276.014 | < 0.001 |

| Others | 43 (5.1) | 82 (6.8) | 274 (27.2) | 42 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1241.279 | < 0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 244 (29.1) | 385 (31.8) | 434 (43.1) | 310 (33.0) | 544 (37.0) | 622 (39.2) | 574 (40.4) | 69.080 | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 191 (22.8) | 303 (25.1) | 344 (34.2) | 254 (27.0) | 464 (31.6) | 540 (34.0) | 509 (35.8) | 80.613 | < 0.001 |

Accordingly, the seven clusters were labeled as follows: Cluster one, “television, news portals and clients, minimal social media”; cluster two, “WeChat, television, radio, and news portals”; cluster three, “WeChat, MicroBlog, and news portals, minimal traditional media”; cluster four, “QQ, WeChat, news portals, and television, minimal newspaper and radio”; cluster five, “television, WeChat, and news portals, no newspaper and radio”; cluster six, “news portals and clients, and WeChat, no newspaper and radio”; and cluster seven, “news clients and WeChat, no newspaper, radio, and news portals”. The seven clusters differed significantly in terms of all demographic and infection-related characteristics and the prevalence of poor COVID-19 knowledge (P < 0.001), except for the prevalence of COVID-19 infection among family members or close relatives (Table 3).

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Cluster 7 | χ2/F | P value | |

| Females | 370 (44.1) | 687 (56.8) | 689 (68.4) | 531 (56.5) | 944 (64.3) | 1004 (63.3) | 983 (69.1) | 190.479 | < 0.001 |

| Age, years | 34.48 ± 12.91 | 36.27 ± 10.90 | 33.14 ± 9.00 | 32.83 ± 11.36 | 35.64 ± 10.98 | 36.50 ± 9.45 | 34.81 ± 9.57 | 21.651 | < 0.001 |

| Educational attainment of senior middle school and below | 287 (34.2) | 237 (19.6) | 118 (11.7) | 248 (26.4) | 187 (12.7) | 196 (12.4) | 157 (11.0) | 341.395 | < 0.001 |

| Currently married | 451 (53.8) | 769 (63.6) | 489 (48.6) | 475 (50.5) | 792 (53.9) | 1015 (64.0) | 821 (57.7) | 107.53 | < 0.001 |

| Family members or close relatives infected with COVID-19 | 11 (1.3) | 7 (0.6) | 15 (1.5) | 11 (1.2) | 18 (1.2) | 22 (1.4) | 18 (1.3) | 5.246 | 0.513 |

| Colleagues, friends, or classmates infected with COVID-19 | 50 (6.0) | 110 (9.1) | 81 (8.0) | 79 (8.4) | 156 (10.6) | 176 (11.1) | 146 (10.3) | 24.159 | < 0.001 |

| Worry of COVID-19 infection | 570 (67.9) | 901 (74.5) | 776 (77.1) | 724 (77.0) | 1134 (77.2) | 1265 (79.7) | 1155 (81.2) | 64.045 | < 0.001 |

| Worry of family members’ COVID-19 infection | 711 (84.7) | 1044 (86.4) | 910 (90.4) | 831 (88.4) | 1307 (89.0) | 1443 (90.9) | 1282 (90.2) | 33.785 | < 0.001 |

| Poor COVID-19 knowledge | 106 (12.6) | 88 (7.3) | 52 (5.2) | 98 (10.4) | 57 (3.9) | 39 (2.5) | 52 (3.7) | 168.25 | < 0.001 |

Specifically, cluster one had the lowest prevalence rates of “colleagues, friends, or classmates infected with COVID-19” at 6.0% and “worry about family members’ COVID-19 infection” at 84.7%. Both of these rates were highest in cluster six at 11.1% and 90.9%, respectively. The lowest rate of “worry about COVID-19 infection” was also in cluster one at 67.9%, whereas the highest was in cluster seven at 81.2%. The rates of “colleagues, friends, or classmates infected with COVID-19” were also higher in cluster five, at 10.6%, and cluster seven, at 10.3%. Clusters five and six had higher rates of “worry about COVID-19 infection”, at 77.2% and 79.7%, respectively, whereas clusters three and seven had higher rates of “worry about family members’ COVID-19 infection”, at 90.4% and 90.2% respectively.

Cluster one presented the highest percentage of poor COVID-19 knowledge at 12.6%, whereas cluster six presented the lowest percentage at 2.5%. Clusters five and seven also had low rates of poor COVID-19 knowledge at 3.9% and 3.7%, respectively.

Cluster one had the lowest prevalence of depressive symptoms at 29.1%, whereas cluster three had the highest at 43.1%. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in the other clusters was as follows: 31.8% in cluster two, 33.0% in cluster four, 37.0% in cluster five, 39.2% in cluster six, and 40.4% in cluster seven. Cluster seven had the highest prevalence of anxiety symptoms at 35.8%, followed by 34.2% in cluster three, 34.0% in cluster six, 31.6% in cluster five, 27.0% in cluster four, and 25.1% in cluster two (Table 2). In the unadjusted model, clusters two and four demonstrated a slightly higher, but not significantly different, risk of depressive symptoms compared with cluster one [odds ratio (OR) = 1.14-1.20, P = 0.077-0.183]. Clusters three, five, and seven, however, presented a significantly greater risk (OR = 1.43-1.85, P < 0.001). After further adjustments were made for both the objective and the perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, the previously significant ORs decreased, with three ORs remaining statistically significant. Upon additional adjustment for poor COVID-19 knowledge, clusters three, six, and seven presented a slight increase in the risk of depressive symptoms (OR = 1.28-1.46, P ≤ 0.011) (Table 4). According to the unadjusted model for anxiety, clusters three through seven presented a significantly greater risk of anxiety symptoms than cluster one did (OR = 1.26-1.89, P ≤ 0.039). After additionally controlling for the objective and perceived risk of COVID-19 infection, the five original ORs decreased. However, three retained statistical significance. Upon the final adjustment for poor COVID-19 knowledge, the risk of anxiety symptoms observed in clusters three, six, and seven increased slightly and remained significant (OR = 1.33-1.40, P ≤ 0.005) (Table 4).

| Cluster | Step 0 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 |

| Depressive symptoms | |||||

| Cluster 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cluster 2 | 1.14 (0.94, 1.38), 0.183 | 1.04 (0.86, 1.27), 0.678 | 1.04 (0.85, 1.26), 0.711 | 1.01 (0.83, 1.23), 0.941 | 1.01 (0.83, 1.23), 0.910 |

| Cluster 3 | 1.85 (1.52, 2.24), < 0.001 | 1.52 (1.24, 1.85), < 0.001 | 1.51 (1.23, 1.84), < 0.001 | 1.45 (1.18, 1.77), < 0.001 | 1.46 (1.19, 1.78), < 0.001 |

| Cluster 4 | 1.20 (0.98, 1.47), 0.077 | 1.09 (0.89, 1.34), 0.400 | 1.08 (0.88, 1.32), 0.485 | 1.02 (0.83, 1.26), 0.845 | 1.02 (0.83, 1.26), 0.824 |

| Cluster 5 | 1.43 (1.20, 1.72), < 0.001 | 1.23 (1.02, 1.48), 0.032 | 1.20 (0.99, 1.45), 0.053 | 1.15 (0.95, 1.39), 0.154 | 1.16 (0.96, 1.40), 0.130 |

| Cluster 6 | 1.57 (1.31, 1.88), < 0.001 | 1.37 (1.14, 1.66), 0.001 | 1.35 (1.12, 1.62), 0.002 | 1.27 (1.05, 1.53), 0.012 | 1.28 (1.06, 1.55), 0.009 |

| Cluster 7 | 1.65 (1.38, 1.98), < 0.001 | 1.38 (1.14, 1.66), 0.001 | 1.36 (1.12, 1.64), 0.002 | 1.27 (1.05, 1.54), 0.013 | 1.28 (1.06, 1.55), 0.011 |

| Anxiety symptoms | |||||

| Cluster 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Cluster 2 | 1.14 (0.92, 1.40), 0.232 | 1.00 (0.81, 1.24), 0.983 | 0.99 (0.80, 1.22), 0.932 | 0.95 (0.76, 1.17), 0.608 | 0.9 5(0.76, 1.18), 0.620 |

| Cluster 3 | 1.76 (1.43, 2.17), < 0.001 | 1.47 (1.19, 1.82), < 0.001 | 1.46 (1.18, 1.81), 0.001 | 1.37 (1.10, 1.71), 0.004 | 1.38 (1.11, 1.71), 0.004 |

| Cluster 4 | 1.26 (1.01, 1.56), 0.039 | 1.15 (0.93, 1.44), 0.199 | 1.13 (0.91, 1.41), 0.280 | 1.04 (0.83, 1.31), 0.718 | 1.04 (0.83, 1.31), 0.709 |

| Cluster 5 | 1.57 (1.29, 1.90), < 0.001 | 1.34 (1.10, 1.63), 0.004 | 1.30 (1.07, 1.59), 0.010 | 1.22 (0.99, 1.50), 0.059 | 1.22 (0.99, 1.50), 0.053 |

| Cluster 6 | 1.75 (1.44, 2.12), < 0.001 | 1.47 (1.21, 1.79), < 0.001 | 1.44 (1.18, 1.75), < 0.001 | 1.32 (1.08, 1.62), 0.006 | 1.33 (1.09, 1.63), 0.005 |

| Cluster 7 | 1.89 (1.56, 2.30), < 0.001 | 1.56 (1.28, 1.90), < 0.001 | 1.53 (1.25, 1.86), < 0.001 | 1.40 (1.14, 1.72), 0.001 | 1.40 (1.15, 1.72), 0.001 |

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large-scale study to examine patterns of media consumption and their associations with depressive and anxiety symptoms among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although WeChat, a popular social media platform in China, was preferred by the majority of the study participants, they tended to obtain COVID-19 knowledge from multiple media sources simultaneously. The seven distinct clusters of media consumption identified through cluster analysis along with their significant differences in characteristics suggest the heterogeneity of media consumption behaviors among the pandemic-affected population. The variation in the risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms across the clusters further supports the need to focus on the combined effect of multiple information sources.

Due to the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, the initial lack of information when COVID-19 first emerged, and the sense of uncertainty about the future during the outbreak[24], people were inclined to seek multiple sources of information to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the situation. Moreover, individual media consumption habits played a role. For example, an individual might watch television for key events and trends, browse various news portals for expert opinions and the latest scientific developments, and access social media platforms to share personal experiences and perspectives. As a result, our study revealed an array of combinations of media source consumption within our sample.

Although social media platforms facilitate social connections between individuals during periods of home quarantine and physical distancing, they have been criticized for their stress-inducing effects. These effects are due, first, to the overabundance of unfiltered information, which many be accurate, inaccurate, or even misleading, as well as more emotionally charged communication[6,25]. In contrast, traditional media such as television and digital outlets such as news portals are often regulated and provide reliable information. This may prevent or reduce unnecessary panic or stress caused by misinformation commonly found on social media. Secondly, traditional and digital media present general news, which may be less likely to cause the stress or anxiety associated with personalized content, such as updates on acquaintances’ personal lives on social media platforms during the pandemic[26]. Third, media consumption on traditional and digital platforms is generally time-bound, which may limit the time users are exposed to distressing information. In contrast, social media are designed for continuous engagement[27]. Nonetheless, the potential stress-mitigating effects of traditional and digital media remain understudied in the literature[25].

In the present study, clusters three, six, and seven each demonstrated a significantly higher risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms than cluster one. As detailed in Table 2, one distinguishing feature of cluster one that is - absent in clusters two, six, and seven - is its high proportion of traditional and digital media use, coupled with minimal usage of WeChat and MicroBlog. In comparison, clusters two, six, and seven are characterized by high use of WeChat and MicroBlog, and little engagement with the traditional and digital media. Given the previously mentioned stress-inducing effects of social media and the potential stress-reducing effects of traditional and digital media, these observed cluster differences in the risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms are expected. While clusters two, four, and five were also characterized by high usage of WeChat, these clusters exhibited high levels of traditional and digital media use. We hypothesize that the comparable risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms in clusters two, four, and five relatives to cluster one may be partially attributed to a balancing effect between the positive and negative impacts of these three media sources. The significantly higher rates of perceived risk of COVID-19 infection in clusters three, six, and seven, compared to cluster one, suggest that social media usage may amplify worry and fear related to COVID-19 infection. The decrease in ORs for clusters three, six, and seven relative to cluster one in the adjusted analysis (from step 2 to step 3, Table 4) indicates that the risk perception of infection partly contributes to the onset of depressive and anxiety symptoms among populations affected by the pandemic.

In general, a greater level of knowledge about COVID-19 enables individuals to understand the virus’s characteristics, transmission routes, and symptoms, and the overall epidemic situation more objectively and rationally. This understanding, in turn, reduces the likelihood of unnecessary fears and concerns and helps people avoid excessive worry and panic, thereby reducing the levels of depression and anxiety caused by the pandemic. The significant associations between a greater level of COVID-19 knowledge and lower levels of depression and anxiety among people affected by the COVID-19 pandemic have been confirmed by prior studies[18,28]. Counterintuitively, however, this study shows the highest rate of poor COVID-19 knowledge in cluster one and lower rates of poor COVID-19 knowledge in clusters three, six, and seven. We speculate that the primary reason for this discrepancy is the limited information channels available to cluster one, which relies predominantly on television and news portals. The information sources for clusters three, six, and seven include a mix of traditional, digital, and social media, which transmit COVID-19 knowledge faster and in real time. In addition, information is often presented visually on social media through infographics and videos, which aid in comprehension. However, the minor changes in ORs for clusters three, six, and seven relative to cluster one after adjusting for poor COVID-19 knowledge (step 4, Table 4) suggest that poor COVID-19 knowledge is not a major contributor to depressive and anxiety symptoms.

The present study has several limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional study, so the causal relationships between media consumption preferences and depressive and anxiety symptoms cannot be determined. Second, since convenience sampling was used for recruitment, the representativeness of the sample is limited. Large-scale, representative, and longitudinal studies are warranted to validate the current findings. Third, we did not assess the duration or frequency of consumption of each media source or the content of each media source, such as misinformation and rumors. Such information would deepen our insights into the relationships between media consumption patterns and depressive and anxiety symptoms.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, people typically sourced information from various media outlets simultaneously. During the outbreak in China, media preferences among the general population can be categorized into seven clusters. The lowest prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms was observed in the cluster consisting of “television, news portals and clients, minimal social media”, with a higher prevalence of these symptoms appearing in clusters such as “WeChat, MicroBlog, and news portals, minimal traditional media”, “news portals and clients and WeChat, no newspaper and radio”, and “news clients and WeChat, no newspaper, radio, and news portals”. The high-risk perception of COVID-19 infection partly accounted for these cluster differences in the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms. However, people in the cluster that relied primarily on television, news portals, and clients but seldom used social media had poorer COVID-19 knowledge.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has ended, future pandemics are an inevitable part of human history. Therefore, the findings of this secondary data analysis hold significant public health implications. Communication policies could be designed to channel crucial information toward traditional and digital media sources, which are generally more regulated and reliable. Specifically, to enhance the dissemination of reliable information during future pandemics, communication policies should prioritize integrated campaigns that utilize television broadcasts for consistent, expert-led updates, while simultaneously engaging digital platforms such as news portals and social media to provide real-time alerts and interactive content. Additionally, public health initiatives should include strategies to counter misinformation and promote accurate, health-protective behaviors through the use of a mix of traditional media and reputable online sources.

Policies that promote the regulation of social media content to reduce the spread of fear-based, false, or inaccurate information are also needed. Specifically, to effectively regulate social media during pandemics, platforms could implement stricter content moderation policies that prioritize the removal of misinformation through automated systems and human oversight, while promoting verified content from trusted sources such as health organizations. Social media platforms could implement algorithms to prioritize and prominently display content from reliable health authorities to reduce exposure to false information that may amplify anxiety and depression. Social media could integrate features that allow users to easily filter or limit their exposure to distressing content and enable them to manage their mental health more effectively. Additionally, partnerships with fact-checking organizations could be established to quickly label and correct misleading posts, help users access accurate information, and mitigate the spread of panic-inducing narratives. The use of social media for positive interactions, such as virtual support groups, sharing helpful and uplifting content, and connecting with friends and family, should also be encouraged. Collaboration with mental health professionals to offer real-time support, such as chatbots or live sessions, could provide immediate help and guidance to users who experience heightened mental distress. Finally, educating the public about media literacy may also prove beneficial by equipping people with skills to critically evaluate the credibility of the information they consume. These measures will not only enrich public knowledge on pandemics but also help mitigate the mental health impact of future health crises.

The authors thank all the participants involved in this study for their cooperation and support.

| 1. | Neill RD, Blair C, Best P, McGlinchey E, Armour C. Media consumption and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown: a UK cross-sectional study across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2023;31:435-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chao M, Xue D, Liu T, Yang H, Hall BJ. Media use and acute psychological outcomes during COVID-19 outbreak in China. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;74:102248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Taguchi K, Matsoso P, Driece R, da Silva Nunes T, Soliman A, Tangcharoensathien V. Effective Infodemic Management: A Substantive Article of the Pandemic Accord. JMIR Infodemiology. 2023;3:e51760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Olagoke AA, Olagoke OO, Hughes AM. Exposure to coronavirus news on mainstream media: The role of risk perceptions and depression. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25:865-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Price M, Legrand AC, Brier ZMF, van Stolk-Cooke K, Peck K, Dodds PS, Danforth CM, Adams ZW. Doomscrolling during COVID-19: The negative association between daily social and traditional media consumption and mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2022;14:1338-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bendau A, Petzold MB, Pyrkosch L, Mascarell Maricic L, Betzler F, Rogoll J, Große J, Ströhle A, Plag J. Associations between COVID-19 related media consumption and symptoms of anxiety, depression and COVID-19 related fear in the general population in Germany. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;271:283-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yao H. The more exposure to media information about COVID-19, the more distressed you will feel. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:167-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu JCJ, Tong EMW. The Relation Between Official WhatsApp-Distributed COVID-19 News Exposure and Psychological Symptoms: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e22142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li M, Xu Z, He X, Zhang J, Song R, Duan W, Liu T, Yang H. Sense of Coherence and Mental Health in College Students After Returning to School During COVID-19: The Moderating Role of Media Exposure. Front Psychol. 2021;12:687928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hammad MA, Alqarni TM. Psychosocial effects of social media on the Saudi society during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0248811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen WC, Chen SJ, Zhong BL. Sense of Alienation and Its Associations With Depressive Symptoms and Poor Sleep Quality in Older Adults Who Experienced the Lockdown in Wuhan, China, During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2022;35:215-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, Wang Y, Fu H, Dai J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0231924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1367] [Cited by in RCA: 1299] [Article Influence: 259.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhang YT, Li RT, Sun XJ, Peng M, Li X. Social Media Exposure, Psychological Distress, Emotion Regulation, and Depression During the COVID-19 Outbreak in Community Samples in China. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:644899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ma ZR, Idris S, Pan QW, Baloch Z. COVID-19 knowledge, risk perception, and information sources among Chinese population. World J Psychiatry. 2021;11:181-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Proietti M, Vitolo M, Harrison SL, Lane DA, Fauchier L, Marin F, Nabauer M, Potpara TS, Dan GA, Boriani G, Lip GYH; ESC-EHRA EORP-AF Long-Term General Registry Investigators. Impact of clinical phenotypes on management and outcomes in European atrial fibrillation patients: a report from the ESC-EHRA EURObservational Research Programme in AF (EORP-AF) General Long-Term Registry. BMC Med. 2021;19:256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hendricks RM, Khasawneh MT. A Systematic Review of Parkinson's Disease Cluster Analysis Research. Aging Dis. 2021;12:1567-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Amin F, Sharif S, Saeed R, Durrani N, Jilani D. COVID-19 pandemic- knowledge, perception, anxiety and depression among frontline doctors of Pakistan. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Galić M, Mustapić L, Šimunić A, Sić L, Cipolletta S. COVID-19 Related Knowledge and Mental Health: Case of Croatia. Front Psychol. 2020;11:567368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bokszczanin A, Palace M, Brown W, Gladysh O, Tripathi R, Shree D. Depression, Perceived Risk of COVID-19, Loneliness, and Perceived Social Support from Friends Among University Students in Poland, UK, and India. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:651-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ruan J, Xu YM, Zhong BL. Loneliness in older Chinese adults amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Prevalence and associated factors. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2023;15:e12543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhong BL, Yuan MD, Li F, Sun P. The Psychological Network of Loneliness Symptoms Among Chinese Residents During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:3767-3776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Min BQ, Zhou AH, Liang F, Jia JP. [Clinical application of Patient Health Questionnaire for self-administered measurement (PHQ-9) as screening tool for depression]. Shenjing Jibing Yu Jingshen Weisheng. 2013;13:569-572. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Sun J, Liang K, Chi X, Chen S. Psychometric Properties of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 Item (GAD-7) in a Large Sample of Chinese Adolescents. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9:1709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Su Z, McDonnell D, Wen J, Kozak M, Abbas J, Šegalo S, Li X, Ahmad J, Cheshmehzangi A, Cai Y, Yang L, Xiang YT. Mental health consequences of COVID-19 media coverage: the need for effective crisis communication practices. Global Health. 2021;17:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 51.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Phalswal U, Pujari V, Sethi R, Verma R. Impact of social media on mental health of the general population during Covid-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J Educ Health Promot. 2023;12:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Draženović M, Vukušić Rukavina T, Machala Poplašen L. Impact of Social Media Use on Mental Health within Adolescent and Student Populations during COVID-19 Pandemic: Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:3392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bozzola E, Spina G, Agostiniani R, Barni S, Russo R, Scarpato E, Di Mauro A, Di Stefano AV, Caruso C, Corsello G, Staiano A. The Use of Social Media in Children and Adolescents: Scoping Review on the Potential Risks. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:9960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Xue Q, Xie X, Liu Q, Zhou Y, Zhu K, Wu H, Wan Z, Feng Y, Meng H, Zhang J, Zuo P, Song R. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among primary school students in Hubei Province, China. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;120:105735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |