Published online Apr 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.104042

Revised: February 6, 2025

Accepted: February 24, 2025

Published online: April 19, 2025

Processing time: 86 Days and 20.4 Hours

As a substitute for traditional drug therapy, digital cognitive-behavioral therapy positively impacts the regulation of brain function, which can improve insomnia. However, there is currently a paucity of studies on digital cognitive behavioral therapy as a treatment for insomnia.

To assess digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia regarding its positive impact on brain function.

Participants were randomly assigned to either a go/no-go group or a dot-probe group. The primary outcome was quality of sleep as assessed by the actigraphy sleep monitoring bracelet, Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI), insomnia se

Eighty patients were included in the analysis (go/no-go group: n = 40; dot-probe group: n = 40). We combined the total scale scores of the two groups before and after the intervention in the analysis of covariance. Our study explored whether insomnia symptoms in both groups can be improved by using digital cognitive behavioral therapy instead of trying to compare the two trials; therefore, only one P value is listed. In both groups, we found a short-term time effect on insomnia symptom severity (PSQI: P < 0.001, η2 = 0.336; ISI: P < 0.001, η2 = 0.667; DASS-depression: P < 0.001, η2 = 0.582; DASS-anxiety: P < 0.001, η2 = 0.337; DASS-stress: P < 0.001, η2 = 0.443) and some effect on sleep efficiency (but it was not significant, P = 0.585, η2 = 0.004).

Go/no-go task training of inhibitory function had a short-term positive effect on sleep efficiency, whereas dot-probe task training had a positive short-term effect on emotion regulation.

Core Tip: In recent years, few studies have explored the use of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of insomnia. This paper offers a detailed summary and discussion of the results and mechanisms of the improved sleep efficiency observed after a digital cognitive behavioral therapy intervention. We found that go/no-go and dot-probe tasks exhibited large anti-insomnia effects. Go/no-go task training of inhibitory function had a short-term positive effect on sleep efficiency.

- Citation: Tian XT, Meng Y, Wang RL, Tan R, Liu MS, Xu W, Cui S, Tang YX, He MY, Cai WP. Digital cognitive behavioral therapy as a novel treatment for insomnia. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(4): 104042

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i4/104042.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.104042

Insomnia, one of the most common sleep disorders, is a major public health problem. The worldwide prevalence of insomnia among adults is approximately 10%, while symptoms of insomnia occur occasionally in up to 22% of individuals[1]. People with insomnia experience cognitive functioning problems such as attention deficit, memory loss, and decreased academic productivity. To cope with this phenomenon, digital insomnia cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is recommended as a widely available and applicable first line of treatment[2].

CBT for insomnia (CBT-I) is applicable to people with sleep disorders caused by various factors[3] whose brains are no different from those of other neurotypical persons, lacking organic damage and capable of maintaining normal ph

Digital CBT-I (DCBT-I) is more flexible than the traditional CBT in terms of time and space and can improve sleep efficiency and reduce the severity of insomnia[5], with maintenance of stable efficacy for one year after treatment[6]. Although DCBT-I improves insomnia more slowly, it has proved to be more effective than medical therapy in our research. DCBT-I is also effective for treating insomnia caused by physical diseases, such as breast cancer[7] or Par

In our study, the go/no-go task was used as part of cognitive training to enhance inhibitory ability[9,10]; the dot-probe task was used to train the brain’s ability to regulate emotions[11] to improve the patients’ sleep efficiency and sleep quality by enhancing inhibitory function and emotion regulation ability. While previous trials and studies have focused on the regulation of lifestyle habits such as sleep habits[12], the present study focused on improving cognitive function[13]. It explored the relationship between cognitive function and sleep efficiency, anticipating a positive correlation[14].

We chose the go/no-go task as an intervention because we hypothesized that most people with insomnia have trouble falling asleep or waking up too early because they cannot autonomously suppress many of their thoughts. These thoughts may relate to something that happened during the day, or about something that was left unfinished a few days ago that requires resolution. These thoughts occupy their mind and are constantly revisited; this leads to insomnia and varying degrees of increased anxiety in patients who are unable to fall asleep or who wake up too early after falling asleep. We chose the dot-probe task as an intervention because previous studies have shown that insomnia is caused by impaired emotional regulation, and the dot-probe task is an effective intervention for emotional regulation[15]. We hypothesize that some patients remain affected by emotions when they are about to go to sleep or during sleep and are unable to become calm, which can also lead to insomnia.

Extant literature suggests that remarkably few studies exist of DCBT as the main treatment mode. The research reported here addresses this gap in the literature and lays a foundation for future studies.

Previous trials indicate that treatments for patients with insomnia are extremely limited, being primarily restricted to drug therapy. Although new medications are continually developed, they inevitably have side effects, which may include dependence and withdrawal reactions[16]. As almost all current drugs for insomnia have side effects, DCBT has become the first choice for insomnia therapy, even if the treatment system is not perfect. This study addressed a gap in the clinical application of DCBT-I, with the hope of improving DCBT-I techniques.

Studies also suggest that people with insomnia may have cognitive deficits, which can partially explain their sleep problems[17]. Based on such studies, this study’s goal included promoting research on treating this type of cognitive dysfunction to reduce or eliminate the associated insomnia symptoms. We used DCBT-I creatively to regulate sleep in people with insomnia without external (pharmacological) treatment to improve sleep efficiency.

The study was designed as a longitudinal controlled randomized trial. The individuals whose data are presented here provided written informed consent to publish their case details.

College students between the age of 18 and 25 years who were experiencing insomnia were recruited. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Met the relevant diagnostic criteria in the Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Insomnia in Adults (2023 edition); (2) Were experiencing insomnia and disordered mood as measured by a Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) score of > 6[18]; (3) Were aged 18-25 years (participants with circadian rhythm disorders common in this age range were included); and (4) Exhibited normal consciousness, expression, and cognitive function, and could communicate and sign the informed consent form.

Participants were not eligible for this study if they met one of the following criteria: (1) Confirmed diagnosis of a mental, neurological, or sleep disorder other than primary insomnia; (2) Confirmed diagnosis of mild cognitive im

The device used is the wGT3X-BT body motion recorder, an ActiGraph product, which is currently a wearable device with the most ActiGraph applications. It can be used for 24-hour continuous and real monitoring of the human body’s activity behaviors and physiological activities, such as raw acceleration value, energy consumption, energy metabolism equivalence, activity intensity, activity time, sedentary behavior, heart rate, sleep latency, total sleep length, sleep efficiency and other parameters. The wGT3X-BT body motion recorder has a dynamic range of +/- 8G range three-axis accelerometer. It has a triaxial accelerometer with a dynamic range of +/- 8G, which can record the body’s level of activity with a sampling frequency of 30-100 Hz. It’s wireless Bluetooth smart technology allows the user to wirelessly carry out initialization and data download. Subjects were instructed to wear the device on the wrist of their non-dominant hand.

We corrected the sleep time and sleep duration recorded by the sleep watch system with the daily sleep diary (i.e., the subject’s daily wake-up time, bedtime, and sleep time) to calculate a more accurate sleep efficiency value. Due to the limitations of the wristwatch system, if a subject took off the wristwatch for an extended period of time, the backend of the wristwatch recorded this time as sleep time and calculated it as part of the total sleep duration.

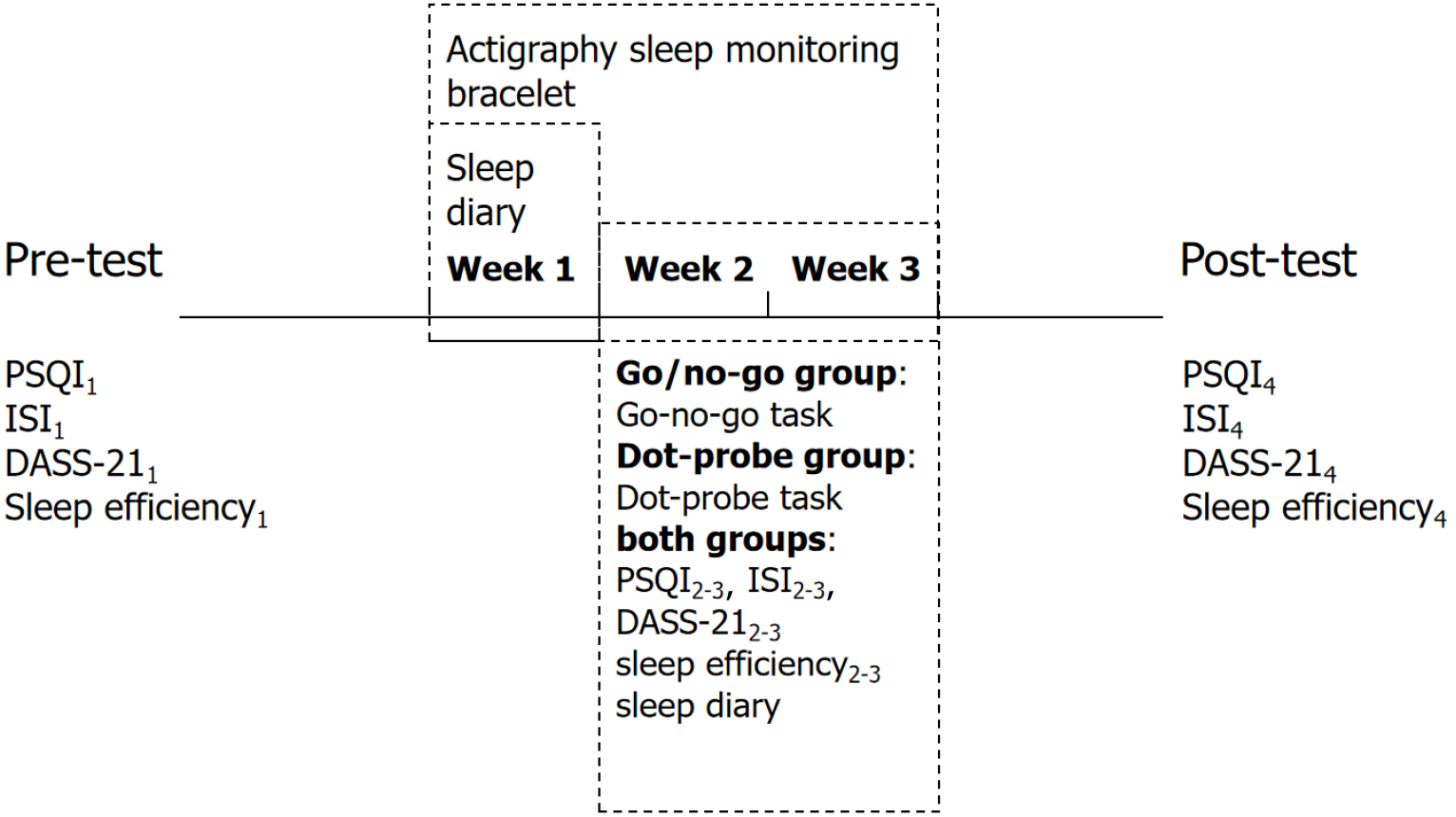

Participants were randomly assigned to either the go/no-go group or the dot-probe group for the 4-week study, as illustrated in Figure 1. A 7-day no-intervention sleep recording was obtained from all 80 participants. For the next 14 days, participants completed either the go/no-go task[19] or the dot-probe task[20].

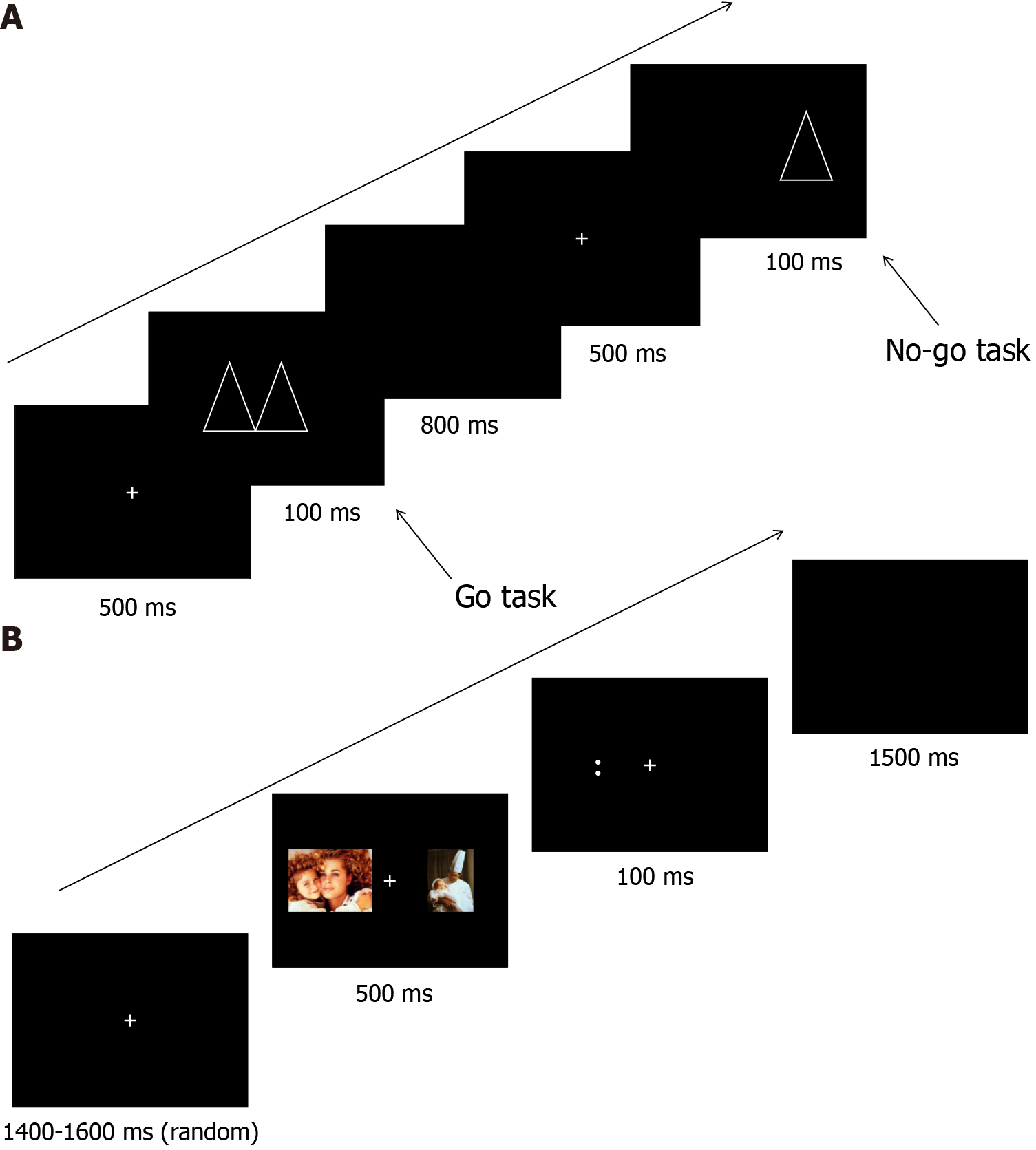

The go/no-go task (Figure 2A) is a psychometric task in which two different patterns are randomly presented alternately on a computer screen. Participants are asked to respond to one of the stimuli by pressing a key on a keyboard (the go response) and not respond to the other stimulus (the no-go response). Erroneous responses to no-go stimuli are often considered an indicator of response cessation difficulties, and the task is used to measure and train inhibitory function. We hypothesize that part of the cause of sleep disorders is weak inhibitory function, wherein the individual is unable to inhibit the manifestation of emotions, such as agitation, nervousness, and excitement, during the sleep period. Therefore, we trained the participants’ inhibitory function through the go/no-go task to improve their sleep efficiency.

The dot-probe task (Figure 2B) is a psychometric task in which, first, two visual stimuli (faces) are displayed on a screen to the participant for 500 ms. The stimuli usually consist of a neutral stimulus and an emotional stimulus (i.e., a face showing a face expression), or two emotional stimuli with different valences. The two stimuli are presented either side of a central fixation. A probe appears on the screen after the stimuli disappear, at which point the participant must react quickly to the position or direction of the probe by key response. This task is used to measure and train the brain’s regulation of emotions and cognitive functions[21]. We hypothesized that sleep disorders may also be caused by impaired or deficient emotion regulation or cognition. We therefore anticipated that the above two methods would be effective at improving the sleep efficiency of people with sleep disorders.

During the study period, all participants received a sleep software intervention every night for 21 days (which included sleep cognitive education, music relaxation, etc.). During the first 7 days of the trial, we did not include any other interventions other than collecting the subjects’ sleep diaries and collecting sleep information through the bracelet. During the remaining 14 days of the trial did we add the above two paradigms to improve the subjects’ sleep by enhancing inhibitory function and emotion regulation function, respectively, along with collecting the subjects’ relevant sleep information as we did in the first 7 days. The functions included in sleep software included: (1) Providing knowledge about sleep; (2) Promoting relaxation by listening to natural sounds or light music; (3) Self-testing of multiple scales; and (4) Learning better methods of falling asleep, such as breathing and relaxation. All participants wore an actigraphy sleep monitoring bracelet to record their sleep every day and submit daily autonomous sleep records (i.e., “sleep diary”)[22,23]. During the 21-day period, all participants completed three questionnaires [PSQI, insomnia severity index scale (ISI), depression anxiety stress scale (DASS-21)][24,25] four times for the measurement of their sleep quality, insomnia severity, depression, anxiety, and stress levels. No psychotropic drugs or sleep-regulating drugs such as oryzanol and melatonin were allowed during these 21 days.

Pre-test data assessment: In addition to basic demographic data, we assessed the participants sleep environment and sleep efficiency before conducting the trial. All participants received a physical examination, which included obtaining their weight and height to calculate BMI. The severity of insomnia symptoms was measured using the PSQI and ISI, and the level of depression, anxiety, and stress by the DASS-21.

A pre-test evaluation of inhibitory function was performed for all participants by their completing the go/no-go task described above, which was compared with their post-intervention performance on this task. All participants received cognitive testing in the evening (18:30-20:30) to control for circadian fluctuations in cognitive performance.

Data assessment during and after intervention period: At the end of the intervention period (three weeks), all measures assessed at pre-test were assessed again using the same methods and procedures. All participants completed the same go/no-go task in the evening. Additionally, the PSQI, ISI, and DASS-21 were assessed after weeks 1 and 2 (during the intervention) to detect sleep disorder symptoms and emotional reactions.

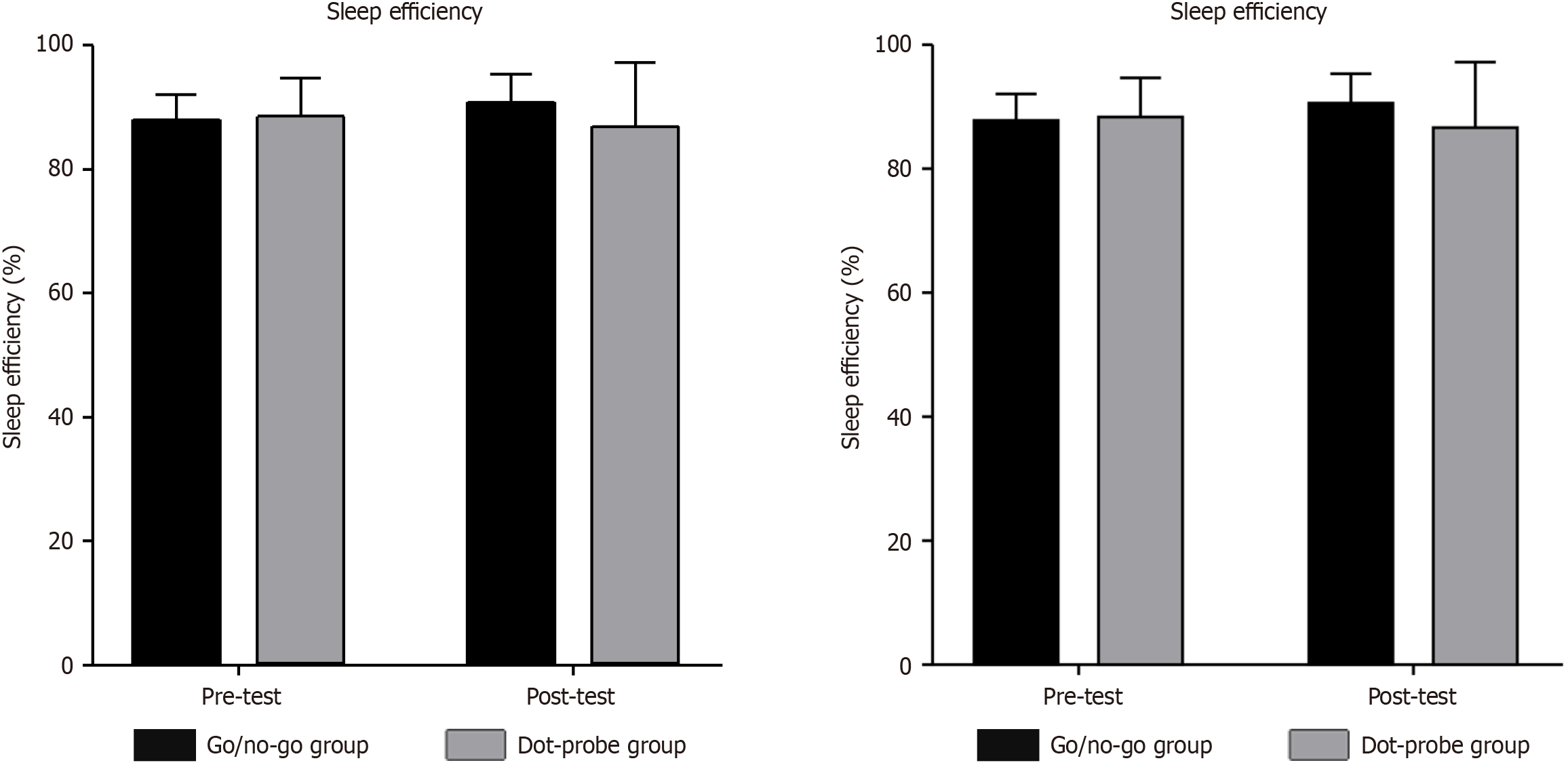

Methods for assessing validity: We first obtained the mean sleep efficiency per night during these 21 days with the help of the actigraphy sleep monitoring bracelets, then calculated the mean sleep efficiency during the first and last seven days. We attempted to further conclude whether the subjects’ insomnia was alleviated after the intervention of the go/no-go task and the dot-probe task by analyzing the trends (increase or decrease) in sleep efficiency before and after the 21-day trial.

Statistical product and service solutions 22.0 was used to conduct the analyses[26]. We used repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) to analyze changes in outcome variables using a between-subjects group factor (go/no-go group and dot-probe group) and a within-subjects time factor (pre-test, post-test). When examining the short-term intervention effects represented by PSQI, ISI and DASS-21 scores, we adjusted the within-subjects time factor to four times (pre-test, week 1, week 2, post-test). To determine whether PSQI, ISI, and DASS-21 scores changed from pre-test to week 1, from week 1 to week 2, and from week 2 to post-intervention, a further series of ANOVAs was conducted in the go/no-go group and the dot-probe group, including one primary time factor, with 95% confidence intervals. In the case of non-normally distributed outcomes, we log-transformed the variables to achieve a normal distribution. The level of statistical significance was defined as an alpha level of 0.05. All analyses were performed using the inter-to-treat method. Missing values were replaced by the last observation continued. We also considered using multiple imputation to replace missing values. However, multiple imputation produced some implausible values, which ultimately became unavoidable.

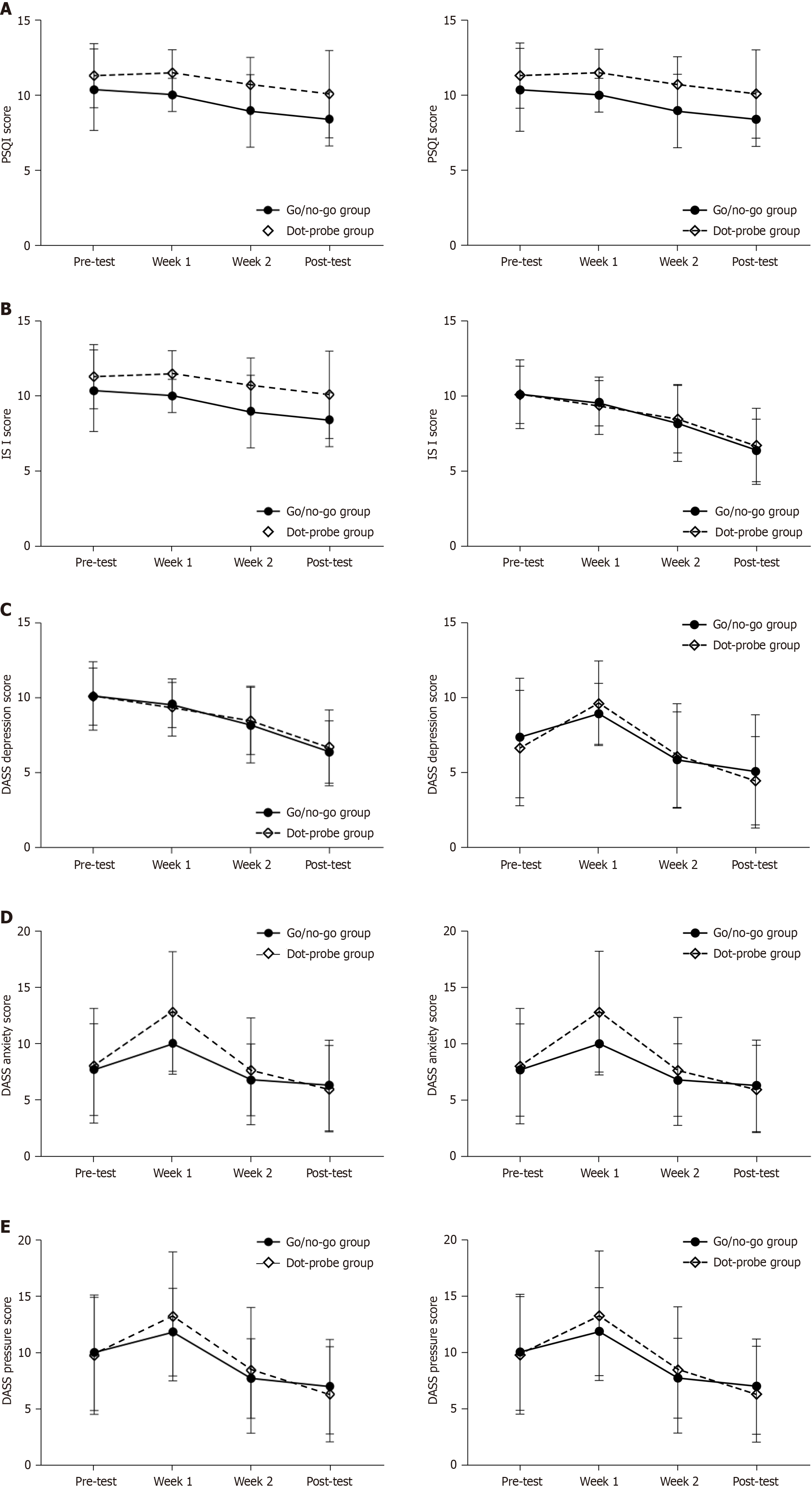

Between April 2023 and June 2023, 118 participants were screened for eligibility, of whom 80 met the inclusion criteria. Among the eligible participants, none refused to participate in the study. Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all 80 participants and no-one withdrew their informed consent prior to randomization into groups. The 80 participants were randomized into a go/no-go group (n = 40) and a dot-probe group (n = 40). At the end of the first week, only half of our subjects were assessed on all three scales, and we believe that the data shedding here has little impact on the overall trend of change. This is because in the first week we only performed the sleep software intervention and not the cognitive paradigm. In terms of the results (Figure 3 and Figure 4), the level of scale scores of the subjects did not improve at the end of the first week, and even increased instead. However, from the beginning of the second week, we conducted a two-week cognitive paradigm intervention. At the end of the second week, there was data shedding for two subjects in the go/no-go group and no data shedding in the dot-probe group; at the end of the third week, there was data shedding for four subjects in both groups. However, the results revealed a gradual decline in scores on all three scales regardless of group, and the magnitude was large. As such, the overall shedding of test data did not possibly affect the general trend of change. At the same time, the fact that the scores of the scales measured at the end of the first weekend did not change significantly, whereas those measured at the end of the second two weekends changed relatively significantly may also indicate that the cognitive paradigm therapy (i.e., a new type of DCBT) is more effective than the traditional CBT in the present trial. All participants also wore the actigraphy sleep monitoring bracelet for the entire 21-day period to record and monitor their sleep and submitted a daily “sleep diary”. A more detailed description of the sample is provided in Table 1. As it shows, no significant differences existed at pre-test between participants assigned to the go/no-go or dot-probe groups in terms of the main study variables (including PSQI, ISI, and DASS-21 scores) and sleep efficiency. Table 1 also shows that the gender distribution was not associated with significant effects in this trial (17.5% of the total sample were female). Our subject recruitment process resulted in a disproportionately high number of male subjects and we did not limit or screen for gender. The reason being that although we know from previous research[27] that women make up a much larger portion of the insomnia population today, we used both paradigms in this study because they are not different for either gender. However, as such, they can be generalized to any gender group. Therefore, we recruited and selected subjects based on PSQI scores only, and did not select subjects based on gender.

| Characteristic | Go/no-go group (n = 40) | Dot-probe group (n = 40) | Total sample (n = 80) | P value (ANOVA) | P value (χ² test) | |||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | |||

| Age | 21 | 1.6 | 20.4 | 1.6 | 20.7 | 1.6 | 0.128 | |

| PSQI | 10.4 | 2.8 | 11.3 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 0.091 | |

| ISI | 20.3 | 4.6) | 20.2 | 3.8 | 20.2 | 4.2 | 0.958 | |

| DASS 1 | 7.3 | 4.0 | 6.6 | 3.8 | 7 | 3.9 | 0.425 | |

| DASS 2 | 7.7 | 4.1 | 8.0 | 5.1 | 7.8 | 4.6 | 0.737 | |

| DASS 3 | 10.1 | 5.2 | 9.8 | 5.2 | 9.9 | 5.2 | 0.83 | |

| Sleep efficiency | 88.0 | 4.1 | 88.94 | 5.6 | 88.5 | 4.8 | 0.423 | |

| Females | 8 (20) | 6 (15) | 14 (17.50) | 0.443 | ||||

We subjected the total scale scores of the two groups before the intervention to the ANOVA analysis together with the post-intervention scores. Our study was intended to explore whether insomnia symptoms in both groups could be improved by using DCBT instead of trying to compare which trial is better. As shown in Table 1 and Table 2, therefore, symptom severity decreased significantly during the treatment period, with both groups showing a significant post-test effect (PSQI: P < 0.001, η2 = 0.336; ISI: P < 0.001, η2 = 0.667; DASS-21-depression: P < 0.001, η2 = 0.582; DASS-21-anxiety: P < 0.001, η2 = 0.337; DASS-21-pressure: P < 0.001, η2 = 0.443). There was no significant group-by-time interaction for the three scale scores (P > 0.05). As shown in the Figure 3 and Figure 4, subsequent pairwise comparisons of individual measurement time points showed elevated scores from pre-test to week 1 (i.e., when there was no intervention); however, there was no effect of the trial because we did not perform any intervention during the first week except testing and assessing subjects’ sleep quality. We suggest that the cause of the elevated scores was specific to the participants and unrelated to the trial. For example, we learned that during the trial, most participants faced many tests, which subjected them to substantial pressure. The intervention period was from week 2 to week 3 (a period of 2 weeks), and we observed a significant decrease in the scores of all three scales in both groups during this period (P < 0.05).

| Characteristic | Pre-test | Post-test | Time | Time × group | ||||||||||

| Go/no-go group | Dot-probe group | Go/no-go group | Dot-probe group | F value | P value | η2 | F value | P value | η2 | |||||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | |||||||

| PSQI | 10.3 | 2.8 | 11.3 | 2.2 | 8.4 | 1.8 | 10.1 | 2.9 | 34.5 | < 0.001a | 0.336 | 0.635 | 0.428 | 0.009 |

| ISI | 20.2 | 4.6 | 20.2 | 3.8 | 12.8 | 4.1 | 13.3 | 5.1 | 140.1 | < 0.001a | 0.667 | 0.377 | 0.541 | 0.005 |

| DASS 1 | 7.3 | 4.0 | 6.6 | 3.8 | 5.1 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 97.4 | < 0.001a | 0.582 | 0.08 | 0.779 | 0.001 |

| DASS 2 | 7.7 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 5.1 | 6.2 | 4.0 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 35.6 | < 0.001a | 0.337 | 0.62 | 0.434 | 0.009 |

| DASS 3 | 10.1 | 5.2 | 9.8 | 5.2 | 7.0 | 4.2 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 55.7 | < 0.001a | 0.443 | 0.113 | 0.738 | 0.002 |

| Sleep efficiency | 88.0 | 4.1 | 88.9 | 5.6 | 90.6 | 4.8 | 87.4 | 9.9 | 0.3 | 0.585 | 0.004 | 5.17 | 0.026a | 0.065 |

Regarding sleep efficiency, pairwise comparisons revealed that improvement was observed from pre-test to post-test in the go/no-go group, while in the dot-probe group, a decrease was observed after sustained intervention (P < 0.05). We conclude that the trial was effective in improving the regulation of inhibitory function, with participants achieving greater sleep efficiency than at pre-test. The data shows that the sleep efficiency of most participants was improved after the experiment, but the sleep efficiency of some suddenly and drastically decreased in the trial’s later stage. We believe that this is likely attributable to these individuals’ personal aspects rather than the experiment’s ineffectiveness. This is because after the later inquiry, they were under substantial pressure, resulting in very little sleep at night. Overall, we confirmed our hypothesis that sleep efficiency can be improved by improving inhibitory function, thereby helping people with sleep disorders to improve their sleep.

The key finding of this study is that the sample with insomnia had varying degrees of short-term improvement in various symptoms (PSQI, ISI, DASS) after task treatment in two different modalities (go/no-go task and dot-probe task). The exact effect sizes for the various measurements indicated in the Figure 3 and Figure 4 are provided in Table 3. This was evidenced by a corresponding decrease in scale scores; that is, all demonstrated short-term positive effects. In addition, the improved inhibitory function engendered by the go/no-go task is more effective at enhancing sleep efficiency than the improved emotion regulation fostered by the dot-probe task. We classify the sleep knowledge education and music relaxation therapy included in the sleep software as part of the DCBT along with the above two paradigms; the former as part of the traditional CBT and the latter as part of the innovation that we have added in this study. Since “the two paradigms work together in a holistic manner to improve the subjects’ sleep status” we consider this new digital cognitive-behavioral therapy proposed in this study to be effective in the treatment of sub-clinical patients. Admittedly, we lacked a placebo control group, and there is some error in deriving the results. As such, we have proposed further measures to optimize the experimental protocol for future trials in the “Limitations” section. Since the subjects were selected from a school rather than a hospital, they had little access to real clinical insomnia patients. The selected subjects all complained of difficulty in falling asleep, while a small number had early awakenings. However, the results we made in this trial are likely to be equally valid for clinical cases. Because this trial improved the subjects’ sleep by improving their cognitive functioning, this approach is also applicable in a clinical context.

| Characteristic | Go/no-go group | Dot-probe group | ||||

| mean | SD | n | mean | SD | n | |

| Sleep efficiency | ||||||

| Pre-test | 88.044 | 4.064 | 40 | 88.941 | 5.582 | 36 |

| Post-test | 90.628 | 4.833 | 40 | 87.362 | 9.938 | 36 |

| PSQI | ||||||

| Pre-test | 10.35 | 2.76 | 40 | 11.3 | 2.174 | 40 |

| Week 1 | 10 | 1.124 | 20 | 11.5 | 1.539 | 20 |

| Week 2 | 8.95 | 2.449 | 38 | 10.7 | 1.87 | 40 |

| Post-test | 8.389 | 1.793 | 36 | 10.059 | 2.943 | 34 |

| ISI | ||||||

| Pre-test | 20.25 | 4.617 | 40 | 20.2 | 3.824 | 40 |

| Week 1 | 19.1 | 3.024 | 20 | 18.7 | 3.813 | 20 |

| Week 2 | 16.42 | 5.15 | 38 | 16.95 | 4.489 | 40 |

| Post-test | 12.778 | 4.134 | 36 | 13.278 | 5.091 | 36 |

| DASS 1 | ||||||

| Pre-test | 7.3 | 3.976 | 40 | 6.6 | 3.822 | 40 |

| Week 1 | 8.9 | 2.024 | 20 | 9.6 | 2.836 | 20 |

| Week 2 | 5.84 | 3.192 | 38 | 6.1 | 3.463 | 40 |

| Post-test | 5.056 | 3.787 | 36 | 4.444 | 2.932 | 36 |

| DASS 2 | ||||||

| Pre-test | 7.65 | 4.092 | 40 | 8 | 5.124 | 40 |

| Week 1 | 10 | 2.791 | 20 | 12.8 | 5.347 | 20 |

| Week 2 | 6.74 | 3.202 | 38 | 7.55 | 4.788 | 40 |

| Post-test | 6.222 | 4.036 | 36 | 5.944 | 3.847 | 36 |

| DASS 3 | ||||||

| Pre-test | 10.05 | 5.179 | 40 | 9.8 | 5.209 | 40 |

| Week 1 | 11.9 | 3.932 | 20 | 13.3 | 5.732 | 20 |

| Week 2 | 7.74 | 3.539 | 38 | 8.5 | 5.588 | 40 |

| Post-test | 7 | 4.222 | 36 | 6.333 | 4.276 | 36 |

Our trial was innovative in that it trained two different cognitive characteristics through two tasks, thereby enhancing brain function and improving insomnia symptoms. We believe that these two tasks train two different cognitive abilities through two distinct pathways but achieve the same positive outcome, namely improving sleep efficiency. The go/no-go task enhances cognitive abilities through the pathway of training to improve inhibition and achieves the result of improving sleep efficiency. The dot-probe task enhances attentional bias toward emotional stimuli through training and thereby improves sleep efficiency.

Our findings are consistent with those of Magnuson et al[28], namely that the accuracy and response times of persons with insomnia on the go/no-go task are not as good as those of people with normal sleep. One of the trial’s major innovations was improving inhibitory ability by training the go/no-go task in people with insomnia. This suggests that one of the reasons for insomnia is diminished inhibitory function compared with that of people with normal sleep. The former group cannot inhibit numerous thoughts, which leads to the occurrence of sleep disorders. The training is expected to alleviate the sleep disorder by enabling the patients to better inhibit various thoughts and emotions that occur peri-sleep, so that they can fall asleep more effectively. These points were also suggested by Magnuson et al[28]. The trial results met our expectations. We found an increase in sleep efficiency in the Go/no-go group in a before and after comparison of sleep efficiency. We then analyzed the sleep efficiency of all 80 subjects in both groups before and after the intervention and found that, overall, the interaction between time and group yielded a significant difference in sleep efficiency (P < 0.05), which means that, overall, our intervention improved the level of sleep efficiency of the subjects and there is a certain degree of correlation between the two groups.

Our data also showed statistically significant reductions in PSQI, ISI, and DASS-21 scores for both groups, and the intervention’s impact was greater in the go/no-go group than expected, as reflected by a better treatment effect than in the dot-probe group. This suggests that the emotion regulation embodied in dot-probe task also has a positive effect on insomnia, but not to the same extent as the inhibitory function trained by the go/no-go task. This may be due to the different sensitivities of different participants to different trial methods[29]. We suggest that both tasks positively impact mood and sleep regulation in insomnia, and they can be used as clinical treatments. The current trial supports this conclusion.

The go/no-go task improved the participants’ sleep efficiency, and follow-up assessments showed that the participants’ sleep condition improved following this treatment. In contrast, regarding the fact that the go/no-go group showed improved sleep efficiency whereas the dot-probe group showed reduced sleep efficiency, we suggest that this can be explained by the fact that the sleep efficiency of a very small number of participants dropped drastically for personal reasons; they experienced a major shock during the treatment period (such as failure in exams)[30], which rendered the treatment ineffective. This information was obtained in later co-subject interviews. Partial damage that occurred to the actigraphy sleep monitoring bracelet resulting in missing or inaccurate recorded data could also have contributed to these unexpected results. Regardless, the sleep efficiency of the group that received go/no-go training improved, which is a positive outcome. Nonetheless, some external factors (e.g., the later stages of this trial coincided with the onset of an exam month) likely affected the sleep efficiency in the post-test data (for instance, the participants were likely revising for their exams). This also leads us to believe that our trial would yield even clearer results in the absence of such external factors[31]. Conversely, we believe that dot-probe training for emotion regulation can improve sleep efficiency to some extent, and we will investigate this further in subsequent trials.

We measured the participant’s perceived sleep (as reflected in the sleep diary) throughout the study period; we verified that the data collected by the actigraphy sleep monitoring bracelet, which participants wore for the 21-day period, matched the sleep diary. The sleep time recorded by the watch is relatively accurate and has a small margin of error (within about a quarter of an hour). This ensured that the data were accurate; it prevented any errors caused when the system incorrectly judges that the participants are in a sleep state when the bracelet is removed for long periods. Owing to equipment problems, we discovered that if the watch is not worn continuously and is removed, it will record the unused time as sleep time. Finally, participation in a trial on the treatment of sleep disorders may have acted as a sleep-promoting placebo, regardless of group assignment. We will ameliorate and focus on this issue in future studies.

Our findings can be summarized as follows. First, the go/no-go task training of inhibitory function appeared to have a positive short-term (at least during the training schedule) impact on sleep and emotional regulation in people with sleep disorders. Second, the dot-probe task training appeared to have some positive short-term effects on emotion regulation but little or somewhat negative effects on sleep efficiency. Third, compared with the pre-test, both groups showed short-term improvements in the three scales’ scores, sleep efficiency, and the self-rated sleep diary; in part, this may be because of the psychological placebo effect of participating in this sleep regulation trial. Regardless, the success of our trial is noteworthy: After excluding invalid data, training on both of the go/no-go task and dot-probe tasks was effective in improving the participants’ condition of insomnia.

The preliminary study confirmed the effectiveness of the two task-treatments and the actigraphy sleep monitoring bracelet for collecting sleep data. We plan to produce sleep regulation software that can interact with the two tasks, so that clinical treatment will no longer rely solely on medication. The side effects of drug treatment have been confirmed in practice, including damage to the patient’s mental state[32]; this study suggests a better, harmless solution for clinically treating sleep disorders. By training the patient’s brain function and their sleep regulation ability to improve sleep efficiency, the patient can fall asleep without depending on medications and by adopting a passive approach to sleep. The two tasks are applicable to different groups of people; both tasks can be used, to benefit from their different effects, or more suitable treatment plans and tasks can be determined according to a patient’s specific circumstances. It is expected that the 21-day short-term treatment can substantially improve a patient's sleep disorder by making it easier for the patient to fall asleep and by improving sleep efficiency.

The go/no-go task and the dot-probe task, as types of DCBT for insomnia, showed some effect in promoting improved sleep. Although prior research is consistent with our findings[33], repeating this study using subjects undergoing traditional clinical treatment as a control group is essential for drawing more precise conclusions. Additionally, we revealed a significant and clinically relevant short-term effect of the go/no-go task and the dot-probe task on cognitive function, which in turn improved sleep efficiency. Since only few treatments were needed to improve the cognitive function of participants with insomnia, the findings have clinical relevance, representing important findings for the field of CBT treatments for insomnia, specifically DCBT.

The trial had several limitations. First, the participants in this study were all healthy college students who did not meet the diagnostic criteria for clinical sleep disorders. They only perceived that they experienced sleep disorders, and reported difficulty falling asleep or early nocturnal awakening. They were not clinically classified as experiencing sleep disorders. Therefore, the effectiveness of this research method for patients with insomnia in clinical practice requires further research and evaluation to determine whether the method can be used as a clinical treatment. Second, our evaluation of sleep was based only on the actigraphy sleep monitoring bracelet and the PSQI scores, lacking any polysomnography for sleep monitoring, which is more authoritative. There was also no evaluation and analysis of physiological indicators, such as melatonin. Third, this study’s effectiveness in short term treatment was confirmed, but there was no long-term follow-up; the long-term effects require further verification. Fourth, we did not include a no-treatment control group in this experiment; rather, this was a longitudinal study that assessed whether each participant’s sleep improved after the trial. As the participants did not know whether the content of the tasks they were trained in had improved their sleep, we believe that placebo effects were unlikely. Nevertheless, if an additional control group were included, it would be possible to more rigorously reject a placebo effect.

As mentioned above, our study could have been improved by recruiting a larger number of both sub-clinical research participants and patients clinically diagnosed with insomnia. We could have emphasized the trial specification to participants before the trial started; for example, to not remove the watch at any time. Additionally, we could have included a no-intervention control group. In addition to using the actigraphy sleep monitoring bracelet and the PSQI scores, we could have added polysomnography, which is a more robust method of determining patients’ daily sleep, alongside measurements of physiological indicators, such as melatonin. After completion of the trial, a follow-up evaluation a few months later would have verified the trial’s long-term therapeutic effect. We also need to analyze the sleep efficiency data in more detail, possibly including individual participant trajectories and survey participant-specific characteristics, as well as rate whether the watch technical issues had a significant impact on the final results. The subjects’ cognitive levels before and after the trial should also be measured and included in the analyses to observe trends in this data. To the best of our knowledge, there is a paucity of similar studies; this study therefore adds valuable findings to the body of evidence in this field, and suggests another effective option for the clinical treatment of sleep disorders.

Overall, our experiments showed that both the go/no-go task and the dot-probe task played a role in effectively treating people with insomnia by improving their sleep quality. Both tasks can be integrated into currently available DCBT for the clinical treatment of people with sleep disorders or for the prevention and treatment of sub-clinical symptoms of poor sleep. The tasks can be widely used as a tool to improve sleep quality and play a greater role in clinically treating sleep disorders.

| 1. | Morin CM, Jarrin DC. Epidemiology of Insomnia: Prevalence, Course, Risk Factors, and Public Health Burden. Sleep Med Clin. 2022;17:173-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 90.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang C, Liu Y, Guo X, Liu Y, Shen Y, Ma J. Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Using a Smartphone Application in China: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e234866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dewald-Kaufmann J, de Bruin E, Michael G. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-i) in School-Aged Children and Adolescents. Sleep Med Clin. 2019;14:155-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Luik AI, Kyle SD, Espie CA. Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (dCBT) for Insomnia: a State-of-the-Science Review. Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2017;3:48-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kyle SD, Hurry MED, Emsley R, Marsden A, Omlin X, Juss A, Spiegelhalder K, Bisdounis L, Luik AI, Espie CA, Sexton CE. The effects of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on cognitive function: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2020;43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kaldo V, Jernelöv S, Blom K, Ljótsson B, Brodin M, Jörgensen M, Kraepelien M, Rück C, Lindefors N. Guided internet cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia compared to a control treatment - A randomized trial. Behav Res Ther. 2015;71:90-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zachariae R, Amidi A, Damholdt MF, Clausen CDR, Dahlgaard J, Lord H, Thorndike FP, Ritterband LM. Internet-Delivered Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:880-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Patel S, Ojo O, Genc G, Oravivattanakul S, Huo Y, Rasameesoraj T, Wang L, Bena J, Drerup M, Foldvary-Schaefer N, Ahmed A, Fernandez HH. A Computerized Cognitive behavioral therapy Randomized, Controlled, pilot trial for insomnia in Parkinson Disease (ACCORD-PD). J Clin Mov Disord. 2017;4:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Terasawa K, Tabuchi H, Yanagisawa H, Yanagisawa A, Shinohara K, Terasawa S, Saijo O, Masaki T. Comparative survey of go/no-go results to identify the inhibitory control ability change of Japanese children. Biopsychosoc Med. 2014;8:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mirajkar S, Waring JD. Aging and task design shape the relationship between response time variability and emotional response inhibition. Cogn Emot. 2023;37:777-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Winer ES, Salem T. Reward devaluation: Dot-probe meta-analytic evidence of avoidance of positive information in depressed persons. Psychol Bull. 2016;142:18-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nguyen-Michel VH, Pallanca O, Brion A, Vecchierini MF. [Sleep habits and lifestyle of elderly patients with insomnia]. Soins Gerontol. 2019;24:38-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mirchandaney R, Barete R, Asarnow LD. Moderators of Cognitive Behavioral Treatment for Insomnia on Depression and Anxiety Outcomes. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2022;24:121-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sewell KR, Erickson KI, Rainey-Smith SR, Peiffer JJ, Sohrabi HR, Brown BM. Relationships between physical activity, sleep and cognitive function: A narrative review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;130:369-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bantin T, Stevens S, Gerlach AL, Hermann C. What does the facial dot-probe task tell us about attentional processes in social anxiety? A systematic review. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2016;50:40-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Atkin T, Comai S, Gobbi G. Drugs for Insomnia beyond Benzodiazepines: Pharmacology, Clinical Applications, and Discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2018;70:197-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Brownlow JA, Miller KE, Gehrman PR. Insomnia and Cognitive Performance. Sleep Med Clin. 2020;15:71-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17520] [Cited by in RCA: 21998] [Article Influence: 611.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bari A, Robbins TW. Inhibition and impulsivity: behavioral and neural basis of response control. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;108:44-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1099] [Cited by in RCA: 1292] [Article Influence: 107.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | van Rooijen R, Ploeger A, Kret ME. The dot-probe task to measure emotional attention: A suitable measure in comparative studies? Psychon Bull Rev. 2017;24:1686-1717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cai W, Pan Y, Chai H, Cui Y, Yan J, Dong W, Deng G. Attentional bias modification in reducing test anxiety vulnerability: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Krystal AD, Edinger JD. Measuring sleep quality. Sleep Med. 2008;9 Suppl 1:S10-S17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 341] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Smith MT, McCrae CS, Cheung J, Martin JL, Harrod CG, Heald JL, Carden KA. Use of Actigraphy for the Evaluation of Sleep Disorders and Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14:1231-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34:601-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1955] [Cited by in RCA: 3067] [Article Influence: 219.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:335-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6494] [Cited by in RCA: 7551] [Article Influence: 251.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Imboden C, Gerber M, Beck J, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Pühse U, Hatzinger M. Aerobic exercise or stretching as add-on to inpatient treatment of depression: Similar antidepressant effects on depressive symptoms and larger effects on working memory for aerobic exercise alone. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:866-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Buysse DJ. Insomnia. JAMA. 2013;309:706-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 54.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Magnuson JR, Kang HJ, Dalton BH, McNeil CJ. Neural effects of sleep deprivation on inhibitory control and emotion processing. Behav Brain Res. 2022;426:113845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Copay AG, Subach BR, Glassman SD, Polly DW Jr, Schuler TC. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J. 2007;7:541-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 958] [Cited by in RCA: 1239] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Corrêa Rangel T, Falcão Raposo MC, Sampaio Rocha-Filho PA. The prevalence and severity of insomnia in university students and their associations with migraine, tension-type headache, anxiety and depression disorders: a cross-sectional study. Sleep Med. 2021;88:241-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Scott AJ, Webb TL, Martyn-St James M, Rowse G, Weich S. Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;60:101556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 450] [Article Influence: 112.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Modesto-Lowe V, Harabasz AK, Walker SA. Quetiapine for primary insomnia: Consider the risks. Cleve Clin J Med. 2021;88:286-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |