Published online Apr 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.102624

Revised: December 22, 2024

Accepted: January 24, 2025

Published online: April 19, 2025

Processing time: 124 Days and 2.1 Hours

Sex education was introduced early in foreign countries. For example, there is a more systematic sex education system abroad, which can better achieve the popularization of sex education. China's sex education started relatively late, yet there are many problems in the development of sex education in China; for example, college students lack knowledge of sexuality.

To explore the perception of sex education among medical college students.

Students majoring in medicine in a medical school were selected as the survey subjects. Anonymous online questionnaires were used to conduct the survey, and the results were analyzed using GraphPad Prism, SPSS, Microsoft Excel, and other software. The questionnaire was administered to understand the source of sexual knowledge, sexual responsibility, mastery of sexual knowledge, and distress caused by sexual problems.

Most students majoring in medicine had no formal sex education, lacked sexual knowledge, or had a biased understanding of sexual responsibility. This study analyzed future research trends in sex education based on relevant achievements in the Chinese context and abroad to further realize the practical significance and value of sex education popularization in China and provide recommendations for parents and schools at different levels.

Sex education should be conducted among college students, and medical colleges and universities should streng

Core Tip: In this study, taking a medical school student as the research object, an online anonymous questionnaire was released. The questionnaire questions involved "sexual concept", "sexual knowledge", "sexual responsibility", "sexual transmission" and other aspects, according to the survey results, the medical students' mastery of "sexual" knowledge was preliminarily understood, and the existing problems were discussed and suggestions were made.

- Citation: Lv SY, Bao ZC, Liu ZD, Zhang Y, Gu YL, Li BK, Deng YS, Zhang YJ, Zhang Y. Perceptions of sex education among college students: A case study of a medical school. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(4): 102624

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i4/102624.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.102624

College students are the driving force of future society, and universities strive to comprehensively cultivate college students' talents, develop their knowledge, skills, and personal growth to prepare them for the workforce and to foster their civic engagement and social responsibility. The data shows the increasing number of abortions among college students and the emerging phenomenon of unmarried pregnancies, highlighting gaps in young people's sexual health knowledge and awareness. Since the harmony and stability of society, campus civilization, and family relations are closely related to college students' sexual health knowledge and awareness, formal sex education is critical for college students. In this study, we used the students of a Chinese medical school as a case study, investigated the so-called sex problem at different levels, summarized feasible countermeasures, and provided recommendations for the popularization of sex education in universities. The People's Republic of China's exceptionally rich culture emphasizes academic excellence; however, the level of sex education in universities remains insufficient[1]. College students' rapidly developing sexual psychology and sexual physiology are reflected in their curiosity about sexual relationships[2]. Typically between the ages of 18 and 22 years, they would have developed a certain level of cognitive abilities and self-control; however, in terms of mental age, they are not fully mature and have inadequate cognitions of sexual morality and sexual responsibility[3]. Our analysis focuses on school education, family education, and social atmosphere to address this problem.

China's Ministry of Education recently revised its “Guiding Outline for Health Education in Primary and Secondary Schools”[4], but the level of implementation is insufficient[5,6]. Chinese education has historically focused on “what questions the Education Bureau produces, what teachers teach, and what students learn”[7], using grades and promotion rates as criteria for evaluating the quality of students and schools. China's examination-oriented educational system leads to a societal focus on students’ grades and abilities, with scant consideration of students' psychological or physical state

Furthermore, Chinese teachers rarely provide students with sex education guidance[10]. Basic physiological knowledge may be mentioned by biology or natural science instructors in primary and secondary schools[11], but physiological knowledge is only one of the foundational elements of sexual knowledge[12,13]. Lacking comprehensive sexual knowledge and awareness, teachers fail to provide young people with accurate, age-appropriate information about sexuality and their sexual and reproductive health. At higher educational levels, few colleges and universities offer sex education courses or, at most, offer only minor courses in sex education[14]—resulting in a lack of the sexual knowledge and awareness[15].

Most Chinese parents and grandparents have not received sex education[16], and their attitudes are greatly influenced by traditional Chinese culture. Parents avoid talking about sex or talk around this issue rather than directly addressing it [17]. This attitude hinders systematic and standardized sex education, resulting in college students having limited sexual knowledge or mastery of the subject[18].

A negative social atmosphere surrounding the topic of sex sets numerous obstacles to young people's acquisition of sexual knowledge. Ignoring appropriate sexual behavior[19], combined with curiosity results in irresponsible sexual behavior in young people, often leading to pregnancy and disease[20].

These serious issues indicate that the current level of sex education in China is insufficient[21]. Although the literature has recently begun to focus on sex education in China[22], research remains scant[23,24]. The findings of this study can close this gap.

Undergraduates aged between 18 and 22 were selected from among medical majors of a medical school. Electronic questionnaires were distributed to 1400 students and 1357 valid questionnaires were returned, with a recovery rate of 96.92%.

Before distributing the questionnaire, we sought the opinions of experts in related fields to improve the questionnaire further. The questionnaire was administered anonymously, and the data were used only for this survey research. The questionnaire consisted of 20 questions regarding the following six aspects: Basic information, sexual concepts, sexual knowledge, sexual responsibility, sexual confusion, and sexual transmission. First, a preliminary understanding of respondents' gender, majors, growth environment, and hometown orientation was obtained. The types of questions included: Six questions aimed at college students’ sexual concepts, three questions aimed at college students’ mastery of sexual knowledge, three at college students’ understanding of the relationship between sex and responsibility, and three at whether college students were confused about sexual issues, and three questions examined the sources of college students’ sexual knowledge. The survey was conducted when students were out of class, and the QR code was scanned and recycled. After data collection was completed, the data were imported, GraphPad Prism was used for chart design, and SPSS was used for data processing. Correlation analysis of the data was carried out with the composition ratio and four-grid table χ2, and the proportion of each part was obtained using the screening function in Microsoft Excel.

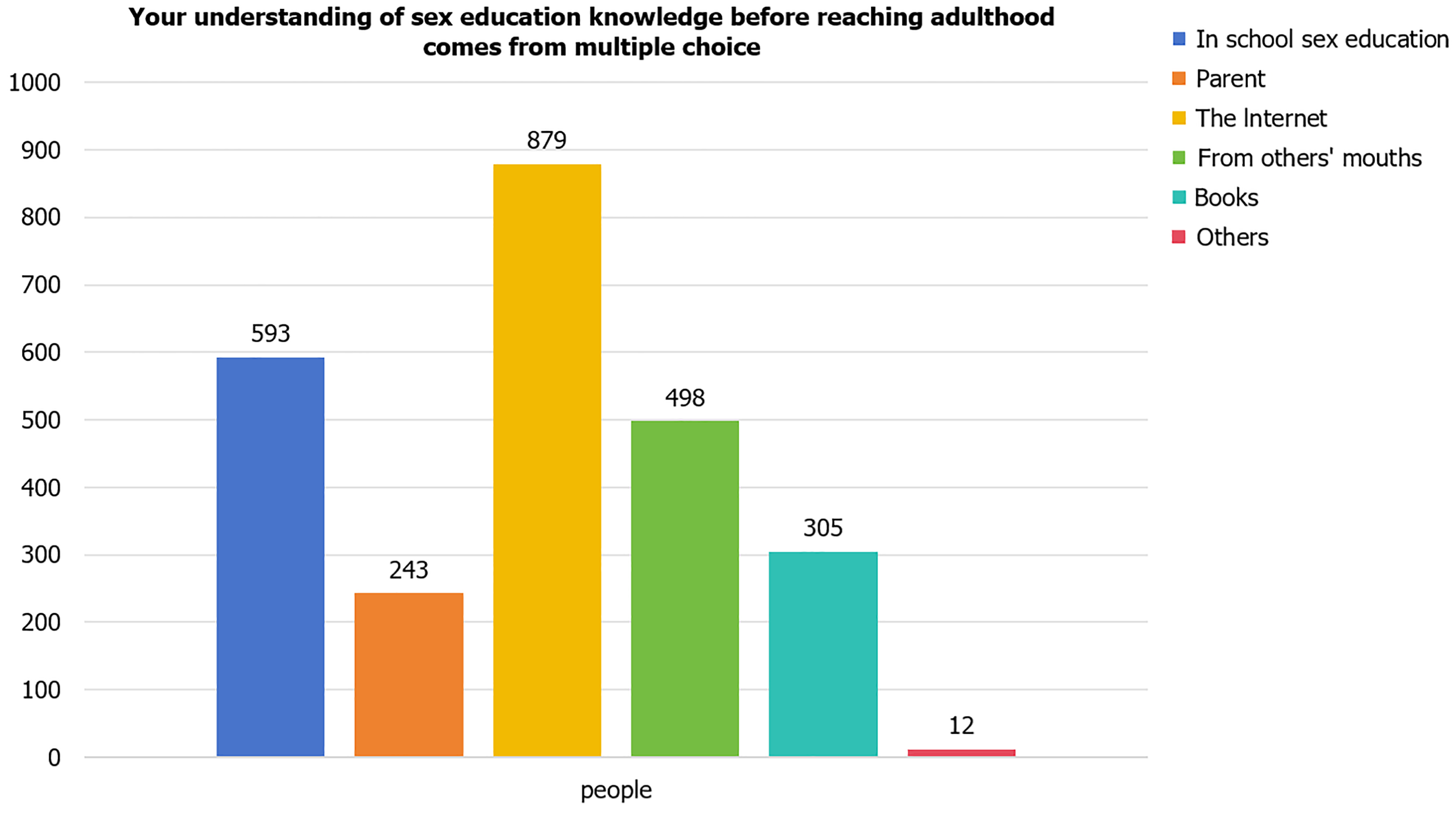

The main sources of sexual knowledge among respondents were the internet and sex education in schools. Of these, 64.6% reported that their sexual knowledge came from the internet, which aligns with the expected results. However, only 17.9% of respondents reported that their sexual knowledge came from parents, indicating that parents, as their children’s first teachers, lack comprehensive sexual knowledge and awareness (Figure 1).

At the macro level, there was no significant difference in the sources of sexual knowledge across different majors. The primary sources of professional knowledge were school-based sex education and the internet. The proportion of parents serving as a source of sexual knowledge ranged from 6.25%-14.81%, consistent with the statistical results observed in the overall population.

At the micro level, the highest proportion of clinical professional knowledge came from the internet (38.02%) and the highest proportion of preventive medicine professional knowledge came from school-based education (32.05%; Table 1). The clinical medical design incorporates a wide range of majors, requiring the research of majors, requiring the research of a large amount of material on the Internet during the learning process, reflecting the characteristics of its disciplines. Therefore, the proportion of sexual knowledge obtained from the Internet was higher than that from other majors. According to the disciplinary attributes of preventive medicine, which mainly studies the basic knowledge of the causes, prevention, screening, control, and elimination of infectious diseases and epidemics, it can be concluded that preventive medicine majors receive more sex education in school than other majors. The experimental results were consistent with this expectation, thereby proving the validity and accuracy of the survey. In the future, relationships among various subjects should be included in the teaching of sexual knowledge.

| Major | In school sex | Parent | Internet | Wordofmouth | Books | Others | Total | ||||||

| Number | Proportion (%) | Number | Proportion (%) | Number | Proportion (%) | Number | Proportion (%) | Number | Proportion (%) | Number | Proportion (%) | ||

| Clinical medicine | 160 | 20.83 | 58 | 7.55 | 292 | 38.02 | 169 | 22.01 | 85 | 11.07 | 4 | 0.52 | 768 |

| Oral medicine | 47 | 26.11 | 24 | 13.33 | 61 | 33.89 | 26 | 14.44 | 22 | 12.22 | 0.00 | 180 | |

| Anesthesiology | 42 | 20.79 | 19 | 9.41 | 70 | 34.65 | 37 | 18.32 | 32 | 15.84 | 2 | 0.99 | 202 |

| Medical imaging | 23 | 24.73 | 6 | 6.45 | 31 | 33.33 | 22 | 23.66 | 11 | 11.83 | 0.00 | 93 | |

| Medical laboratory technology | 27 | 25.96 | 12 | 11.54 | 33 | 31.73 | 18 | 17.31 | 12 | 11.54 | 2 | 1.92 | 104 |

| Preventive medicine | 25 | 32.05 | 9 | 11.54 | 23 | 29.49 | 12 | 15.38 | 9 | 11.54 | 0.00 | 78 | |

| Biotechnology | 13 | 23.64 | 7 | 12.73 | 18 | 32.73 | 10 | 18.18 | 7 | 12.73 | 0.00 | 55 | |

| Psychiatry | 32 | 23.36 | 15 | 10.95 | 48 | 35.04 | 25 | 18.25 | 16 | 11.68 | 1 | 0.73 | 137 |

| Health inspection and quarantine | 22 | 22.92 | 6 | 6.25 | 33 | 34.38 | 24 | 25.00 | 11 | 11.45 | 0.00 | 96 | |

| Traditional Chinese medicine | 22 | 25.58 | 14 | 16.28 | 24 | 27.91 | 17 | 19.77 | 9 | 10.47 | 0.00 | 86 | |

| Nursing (including major upgrade to undergraduate level) | 24 | 22.02 | 11 | 10.09 | 35 | 32.11 | 22 | 20.18 | 16 | 14.58 | 1 | 0.92 | 109 |

| Midwifery | 22 | 30.14 | 8 | 10.96 | 26 | 35.62 | 10 | 13.70 | 7 | 9.59 | 0.00 | 73 | |

| Geriatric care and management | 12 | 22.22 | 8 | 14.81 | 16 | 29.63 | 8 | 14.81 | 10 | 18.52 | 0.00 | 54 | |

| Food quality and safety | 18 | 31.03 | 8 | 13.79 | 17 | 29.31 | 11 | 18.97 | 4 | 6.90 | 0.00 | 58 | |

| Medical information engineering | 15 | 27.78 | 5 | 9.26 | 17 | 31.48 | 11 | 20.37 | 6 | 11.11 | 0.00 | 54 | |

| Pharmacy | 30 | 23.44 | 10 | 7.81 | 43 | 33.59 | 27 | 21.09 | 18 | 14.06 | 0.00 | 128 | |

| Rehabilitation therapy (including rehabilitation therapy techniques) | 36 | 22.50 | 15 | 9.28 | 55 | 34.38 | 35 | 21.88 | 19 | 11.88 | 0.00 | 160 | |

| Bioinformatics | 8 | 22.22 | 5 | 13.89 | 12 | 33.33 | 7 | 19.44 | 4 | 11.11 | 0.00 | 36 | |

| Total | 578 | 23.39 | 240 | 9.71 | 854 | 34.56 | 491 | 19.87 | 298 | 12.06 | 10 | 0.40 | 2471 |

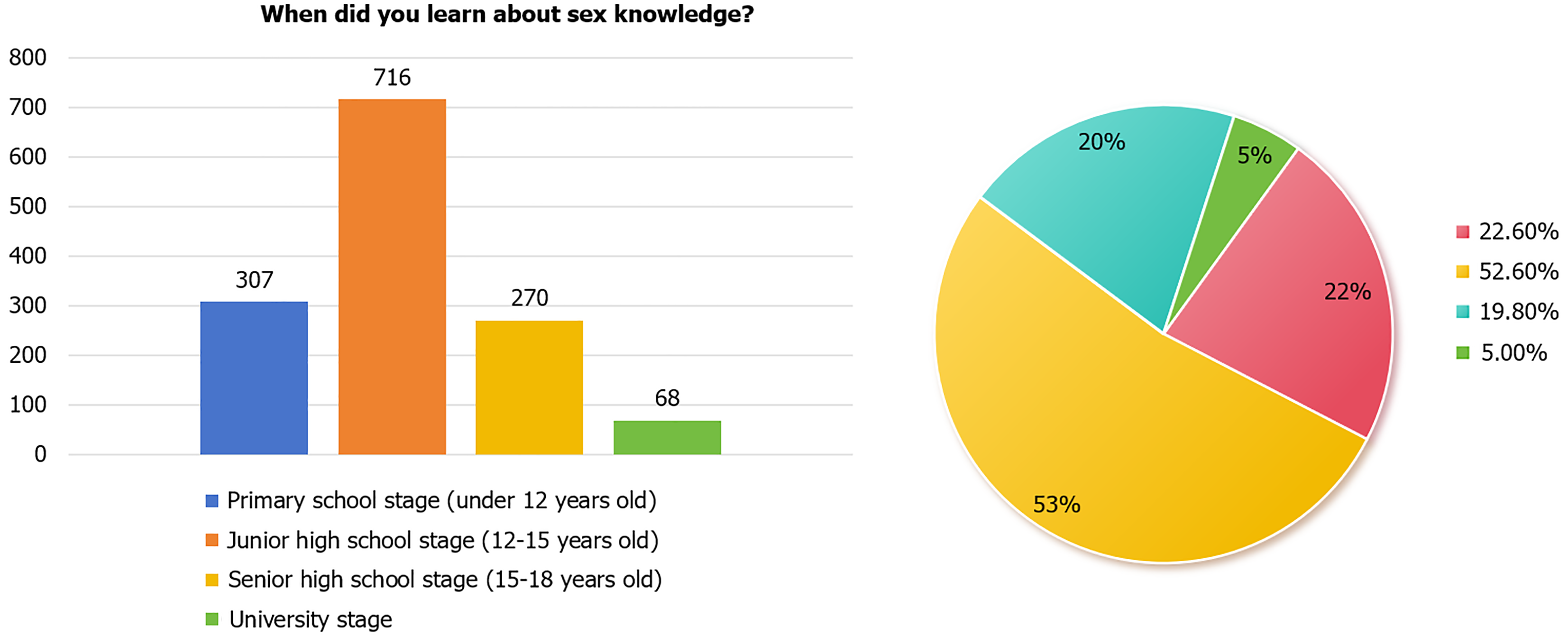

Among medical college students, 52.6% began to understand sexual knowledge in junior high school and 24.8% had some understanding of sexual knowledge in college and high school; that is, 65.2% of the students had a certain understanding of sexual knowledge in primary school and junior high school (Figure 2). Because of their young age, the perception of sexual problems is prone to skew; therefore, there is a need for formal sex education for children in primary schools and junior high schools.

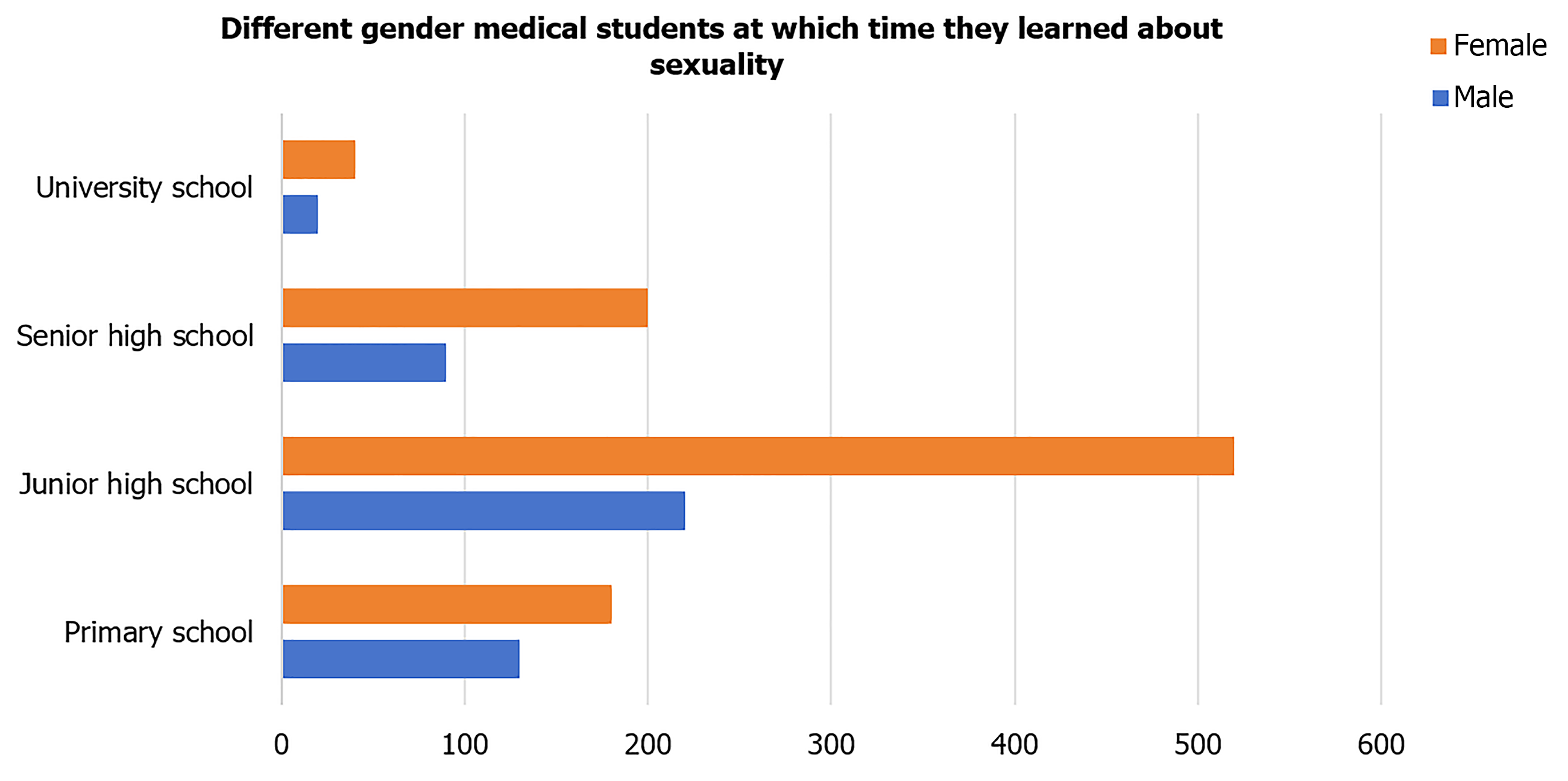

Figure 3 shows the links between gender and the educational stage of understanding sexual knowledge.

At the macro level, the educational stage when young males and young females began to understand sexual knowledge were as follows: Understanding sexual knowledge was concentrated in junior high school, with fewer respondents reporting that their understanding of sexual knowledge began in college, and the proportion of those with sexual knowledge in primary school and high school was similar. This is consistent with the statistical results for all students.

At the micro level, boys were more likely than girls to have sexual knowledge in primary school, and girls were more likely to have sexual knowledge than boys in high school and university. Thus, boys have an earlier understanding of sexual knowledge than girls, and the sources of sexual knowledge are more abundant. A deeper analysis showed that boys were more likely to take the initiative to understand sexual knowledge and engage in sexual thinking. Most girls were uninterested in sexual knowledge during primary school, and were more conservative in their sexual thinking. This demonstrates that conducting separate sex education programs for young males and young females is both scientific and reasonable.

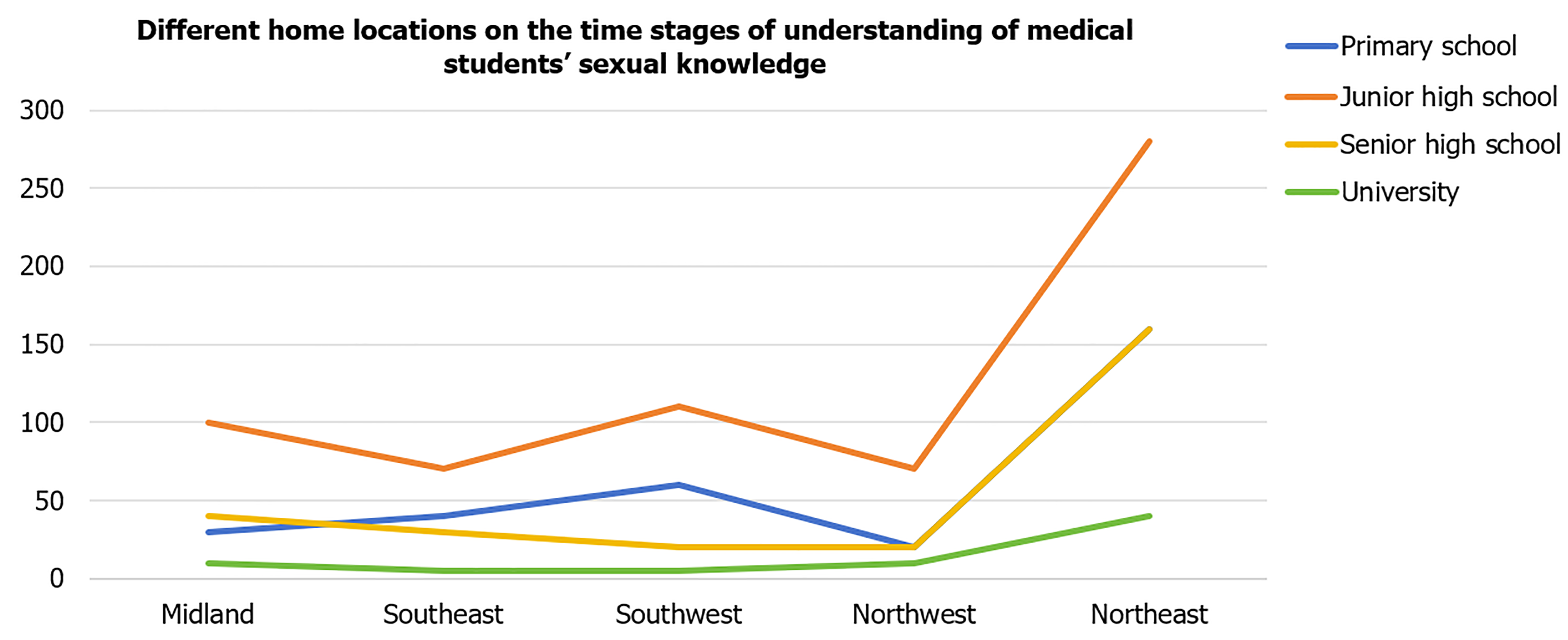

Figure 4 shows the connection between hometown location and educational stage in understanding sexual knowledge.

At the macro level, sexual knowledge was concentrated in junior high school in all regions, less concentrated in colleges, and similar in primary and high schools.

At the micro level, the proportion of students in the Southwest and Southeast China who had sexual knowledge in primary school was significantly higher than that in the Northeast and Northwest China. The proportion of students in the Northeast who had sexual knowledge was the highest in college, and students in the south had a certain understanding of sexual knowledge before college. Thus, there was a certain difference in sexual knowledge between the North and the South, and sex education for children in the south was carried out earlier and will be involved in primary school and junior high school. In this regard, the South’s education model has reference value for the North.

Table 2 shows that educational stage when all majors learned about sexual knowledge was concentrated in junior high school and was less concentrated in college, and the proportion of those whose understanding of sexual knowledge in elementary school and high school was similar. Consistent with the statistical results of all students, it can be seen that the educational stage of understanding of sexual knowledge of students in this medical school was not necessarily related to their major.

| Major | Primary school | Junior high school (12-15 years old) | Senior high school (15-18 years old) | University | Total |

| Clinical medicine | 96 | 241 | 76 | 17 | 430 |

| Stomatology major | 23 | 49 | 15 | 6 | 93 |

| Anesthesiology major | 24 | 58 | 22 | 8 | 112 |

| Medical imaging | 15 | 22 | 10 | 3 | 50 |

| Medical laboratory technology | 11 | 34 | 12 | 2 | 59 |

| Preventive medicine | 10 | 21 | 9 | 1 | 41 |

| Biotechnology | 9 | 15 | 6 | 1 | 31 |

| Psychiatry | 18 | 41 | 7 | 2 | 68 |

| Health inspection and quarantine | 7 | 26 | 10 | 4 | 47 |

| Traditional Chinese medicine | 9 | 22 | 13 | 1 | 45 |

| Nursing (including upgrading to undergraduate level) | 18 | 24 | 16 | 2 | 60 |

| Midwifery | 8 | 24 | 5 | 5 | 42 |

| Geriatric care management | 7 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 25 |

| Food quality and safety | 4 | 15 | 10 | 3 | 32 |

| Medical information engineering | 4 | 13 | 8 | 1 | 26 |

| Pharmacy | 16 | 27 | 12 | 4 | 59 |

| Rehabilitation therapy (including rehabilitation therapy techniques) | 22 | 38 | 21 | 4 | 85 |

| Bioinformatics | 1 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 18 |

| Total | 302 | 695 | 259 | 67 | 1323 |

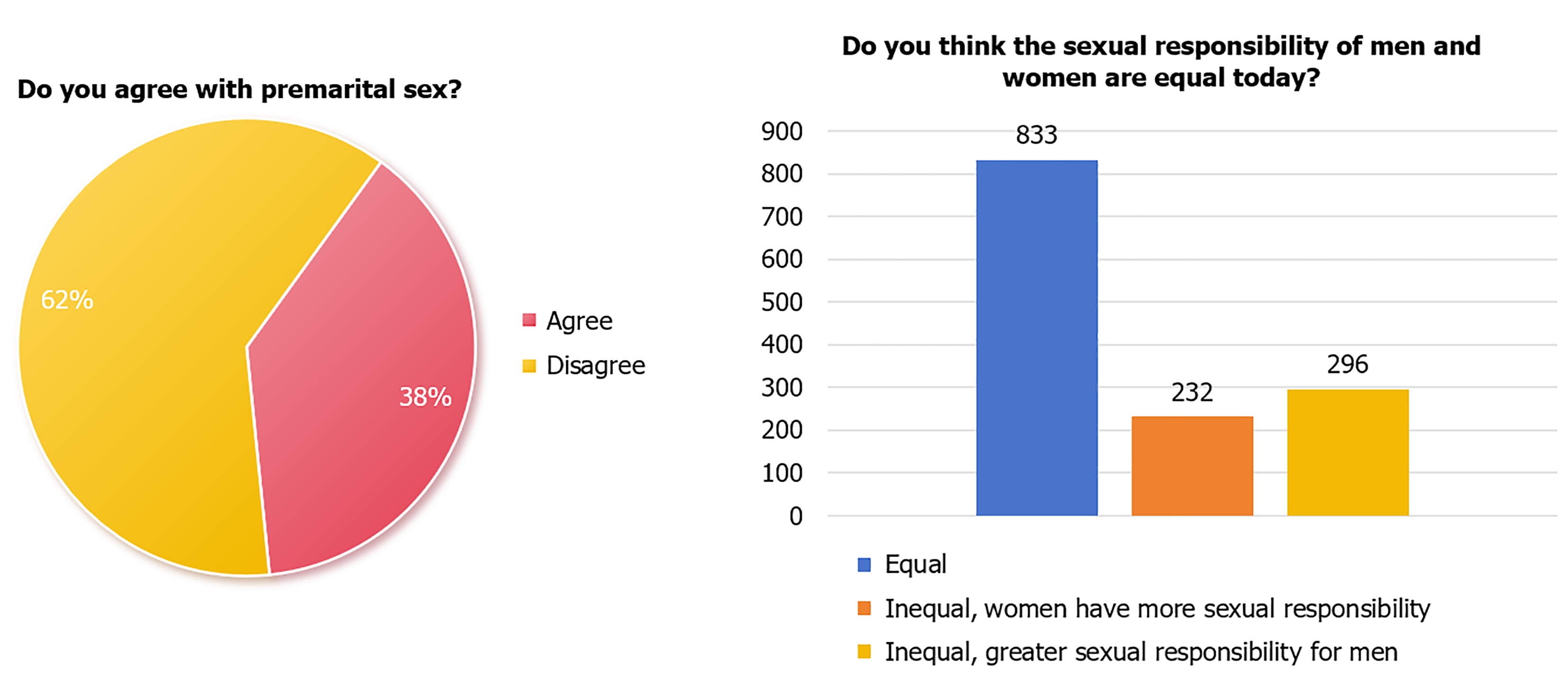

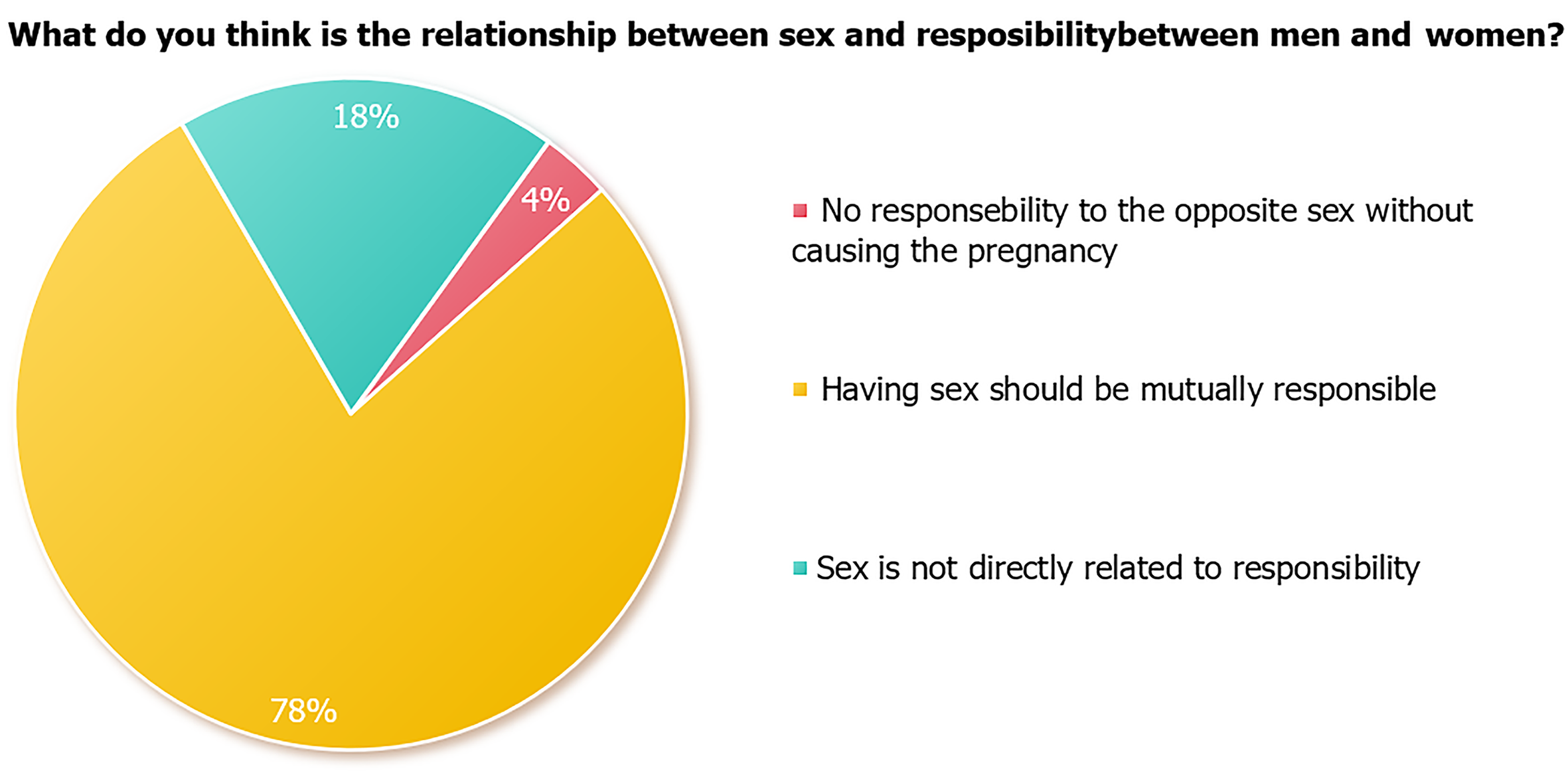

Figure 5 shows the overall sexual responsibility of the survey respondents. The data show that most college students disapproved of premarital sex, believed that males and females had equal sexual responsibilities, and agreed that they should be responsible for each other when having sex. Most of the students had a relatively accurate understanding of their sexual knowledge and responsibilities.

Tables 3, 4 and 5 show the age-specific analysis of sexual responsibility. The statistical population of respondents was divided into two age groups, 18-20 years old and 21-22 years old; the awareness of sexual responsibility in the 18-20 age group was higher than that in the 21-22 year old age group, and 23.86% of students over 20 years old believed that sex was not directly related to responsibility. The result was different from the expectation that as they grow older, students’ sense of sexual responsibility is not only strengthened, but even the minds of the opposite sex are more open-minded. For adults who are about to enter society, this concept should be abandoned, reflecting that colleges and universities should strengthen the standardization of college students’ awareness of sexual responsibility and that it is necessary to continue sex education[14].

| Age | Approval | Oppose | Total | ||

| Quantity | Proportion (%) | Quantity | Proportion (%) | ||

| 18-20 years old | 437 | 37.00 | 744 | 63.00 | 1181 |

| 21-22 years old | 84 | 47.73 | 92 | 52.27 | 176 |

| Total | 521 | 38,39 | 836 | 61.61 | 1357 |

| Age | If you don’t get pregnant, you don’t need to be responsible for the opposite sex | Having sex should be responsible for each other | There is no direct relationship between sex and responsibility | Total | |||

| Quantity | Proportion (%) | Quantity | Proportion (%) | Quantity | Proportion (%) | ||

| 18-20 years old | 39 | 3.30 | 933 | 79 | 209 | 17.70 | 1181 |

| 21-22 years old | 7 | 3.98 | 127 | 72.16 | 42 | 23.86 | 176 |

| Total | 46 | 3.39 | 1060 | 78.11 | 251 | 18.50 | 1357 |

| Age | Equal | Unequal, women are more responsible | More responsibility for men | Total | |||

| Quantity | Proportion (%) | Quantity | Proportion (%) | Quantity | Proportion (%) | ||

| 18-20 years old | 728 | 61.64 | 195 | 16.51 | 258 | 21.85 | 1181 |

| 21-22 years old | 104 | 59.09 | 35 | 19.89 | 37 | 21.02 | 176 |

| Total | 832 | 61.31 | 230 | 16.95 | 295 | 21.74 | 1357 |

Table 6 shows a gender-specific results of sexual responsibility. A correlation analysis was conducted to determine whether sex was related to sexual responsibility or premarital sex. There was no significant difference between sex and equality of sexual responsibility; however, there was a negative correlation. There was a significant difference between gender and premarital sex, which was reflected in the fact that male approval of premarital sex was higher than female approval (P < 0.01). Males are more open-minded when they come into contact with the opposite sex, and have a weaker concept of sexual responsibility. Colleges and universities can adopt gender-specific sex education for both men and women, making sex education more scientific and efficient.

| Sex | Sexual responsibility | Premarital sex | ||

| Sex | Pearson | 1 | -0.014 | 0.13 |

| Sig. | - | 0.615 | < 0.01 | |

| Sexual responsibility | Pearson | -0.014 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Sig. | 0.615 | - | 0.901 | |

| Premarital sex | Pearson | 0.13 | 0.003 | 1 |

| Sig. | < 0.01 | 0.901 | - |

Table 7 shows sexual responsibility by major. The analysis of the cognition of most students from different majors shows that most students have an accurate understanding of sexual responsibility, and there is no significant difference in the cognitive levels of students from different majors.

| Professional | Agree | Disagree | Total | ||

| Number | Proportion (%) | Number | Proportion (%) | ||

| Clinical medicine | 183 | 42.56 | 247 | 57.44 | 430 |

| Oral medicine | 37 | 39.78 | 56 | 60.22 | 93 |

| Anesthesiology | 46 | 41.07 | 66 | 58.93 | 112 |

| Medical imaging | 19 | 38.00 | 31 | 62.00 | 50 |

| Medical laboratory technology | 22 | 37.29 | 37 | 62.71 | 59 |

| Preventive medicine | 13 | 31.71 | 28 | 68.29 | 41 |

| Biotechnology | 10 | 32.26 | 21 | 67.74 | 31 |

| Psychiatry | 27 | 39.71 | 41 | 60.29 | 68 |

| Health inspection and quarantine | 11 | 23.40 | 36 | 76.60 | 47 |

| Traditional Chinese medicine | 12 | 26.67 | 33 | 73.33 | 45 |

| Nursing (including major upgrade to undergraduate level) | 25 | 41.67 | 35 | 58.33 | 60 |

| Midwifery | 16 | 38.10 | 26 | 61.90 | 42 |

| Geriatric care management | 10 | 40.00 | 15 | 60.00 | 25 |

| Food quality and safety | 5 | 15.63 | 27 | 84.38 | 32 |

| Medical information engineering | 12 | 46.15 | 14 | 53.85 | 26 |

| Pharmacy | 31 | 52.54 | 28 | 47.46 | 59 |

| Rehabilitation therapy (including rehabilitation therapy techniques) | 24 | 28.24 | 61 | 71.76 | 85 |

| Bioinformatics | 4 | 22.22 | 14 | 77.78 | 18 |

| Total | 507 | 38.32 | 816 | 61.68 | 1323 |

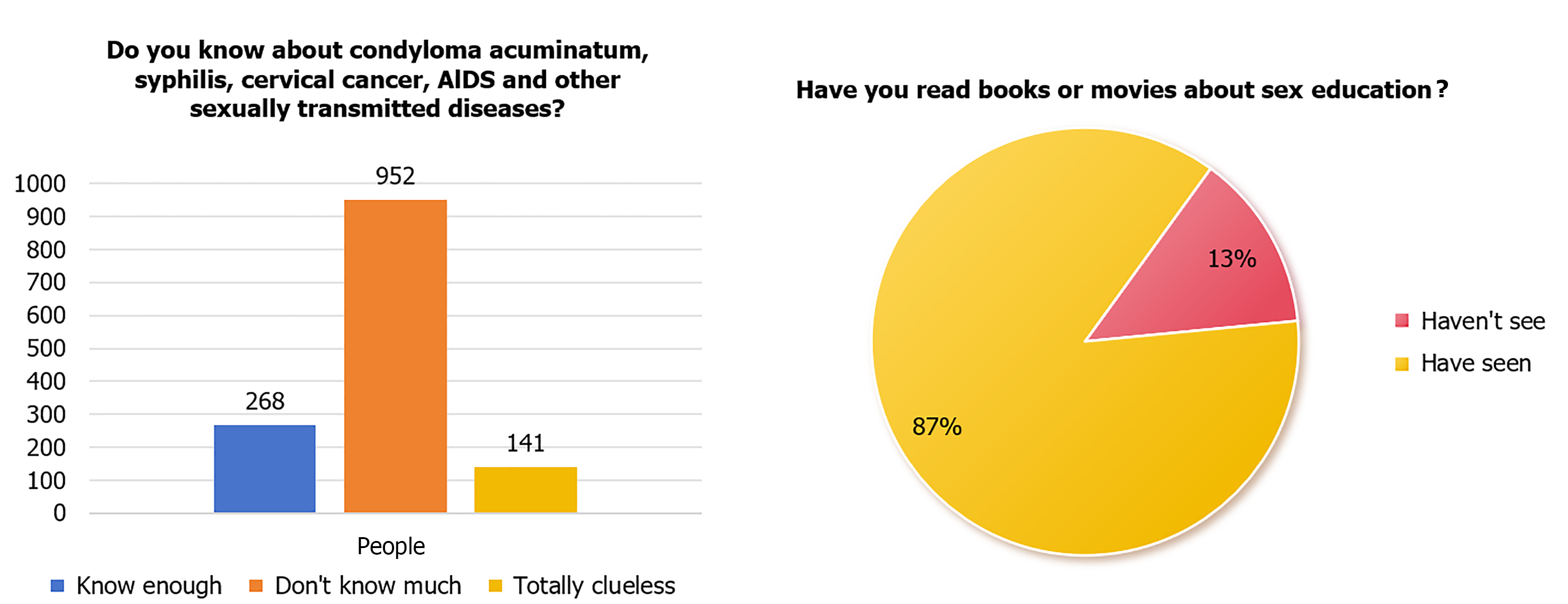

Figure 6 shows the overall mastery of sexual knowledge among respondents.

Nearly half of the respondents reported that their sex knowledge was related to sexpual education books or films. Most students (69.9%) did not know enough about sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and 10.4% of them did not know about STDs at all, indicating that students’ sexual knowledge and safety need to be improved.

Table 8 shows the respondents’ sexual knowledge by gender. The proportion of boys who did not know about STDs at all was similar, but the proportion of boys who knew enough about STDs was 32.04%, which was much higher than that of girls, and most girls’ understanding of sexual knowledge remained at the level of half-understanding. Recent data show that women are more likely to be victims of unfavorable sexual relations. It can be seen that girls’ awareness of sexual safety needs to be improved, sexual knowledge needs to be enriched, and parents and schools should also pay attention to the reasonable development of girls’ sexual safety.

| Sufficient understanding | Not much | Not at all | Total | ||||

| Number | Proportion (%) | Number | Proportion (%) | Number | Proportion (%) | ||

| Male | 141 | 32.05 | 252 | 52.27 | 47 | 10.68 | 440 |

| Female | 126 | 13.74 | 697 | 76.01 | 94 | 10.25 | 917 |

| Total | 267 | 19.68 | 949 | 69.93 | 141 | 10.39 | 1357 |

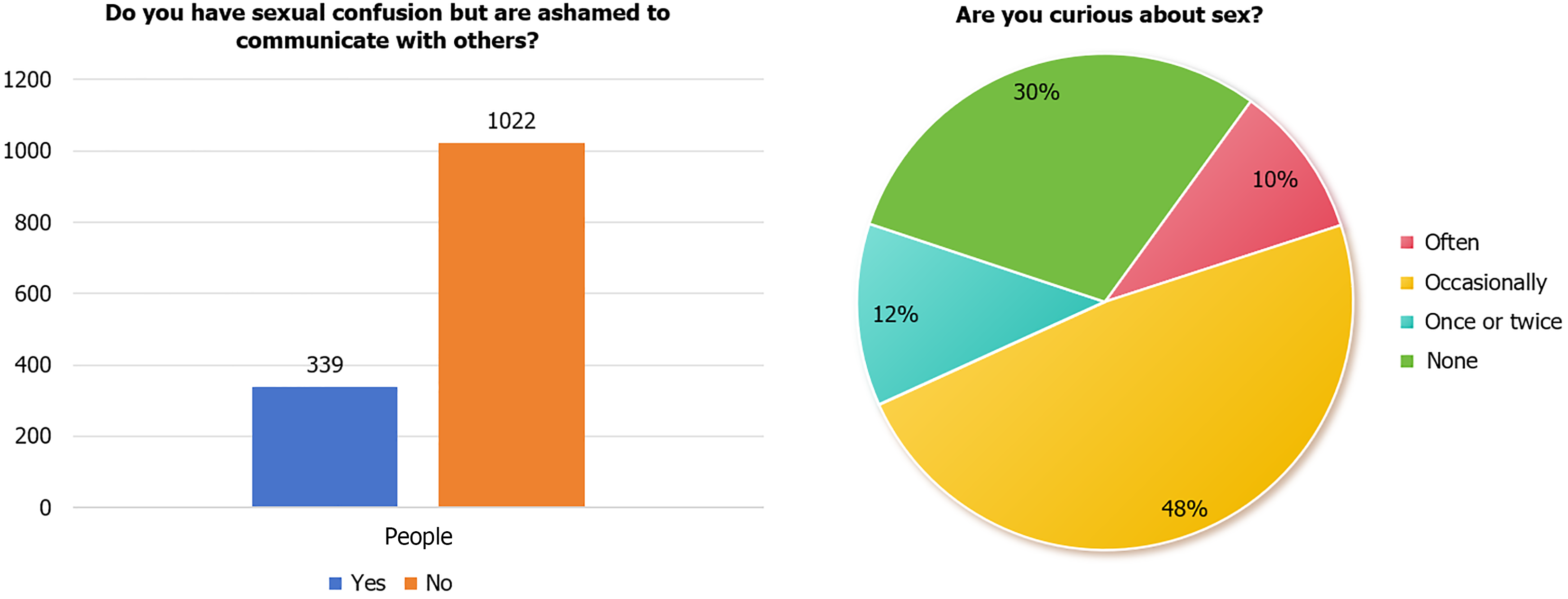

Figure 7 shows the overall distress of students in terms of sexual problems.

According to the data, 24.9% of the students were sexually confused but ashamed of communicating with others, 68.7% longed for sex and were curious about sexual issues, and 14% were interested in pornographic sex and other materials. China’s traditional sexual culture is relatively conservative, leading to problems with college students’ sexuality, which are characterized by unknowns and curiosity. Therefore, college students should accept the proper way to dispel the mystery of sexuality so that they realize that correct sexual behavior must be supervised on scientific knowledge and not self-taught.

Table 9 demonstrates the students’ distress regarding sexual problems and combines the data of the students’ questions “whether they are curious about sexuality” and “whether they are sexually confused but ashamed to communicate with others”.

| Frequency | Yes | No | Total | |||

| Quantity | Proportion (%) | Quantity | Proportion (%) | |||

| Are you curious about sexual matters? | Often | 55 | 40.74 | 80 | 59.26 | 135 |

| Occasionally | 180 | 27.48 | 475 | 72.52 | 655 | |

| Once or twice | 44 | 27.16 | 118 | 72.84 | 162 | |

| None | 58 | 14.32 | 347 | 85.68 | 405 | |

| 337 | 24.83 | 1020 | 75.17 | 1357 | ||

Of the students, 40.74% were often curious about sexual issues but experienced shame in communicating with others (Figure 8). These students should receive the attention of the school or their parents and should be given appropriate channels to understand sexual issues and understand that there is no shame in communicating sexual issues with others.

Table 10 shows the role of parents in the transmission of sexual knowledge. Parents were the first teachers of their children, and their role in transmitting sexual knowledge to children was explored. Of the parents, 20.9% were guardians of their children in terms of sexual knowledge transmission, and 23.7% of the students had experienced deliberate molestation by others but had not informed their parents, indicating that some parents were not doing an adequate job in teaching their children’s sexual knowledge, and they should communicate more with their children.

| It is necessary | There is no need because your own knowledge is enough | ||||

| Quantity | Proportion (%) | Quantity | Proportion (%) | ||

| What is your parent’s identity to you when it comes to sexuality? | Teacher, there are warnings about taboos, and I don’t want to talk about it more, but I have said everything that should be said | 411 | 31.51 | 49 | 3.76 |

| Guard, don’t talk much, and will make up stories in a hurry | 246 | 18.87 | 36 | 2.76 | |

| Friends, who can talk at any time, will hint at what you shouldn’t do, and have a subtle impact | 472 | 36.20 | 70 | 5.37 | |

| Other | 12 | 0.92 | 8 | 0.61 | |

| Total | 1141 | 87.50 | 163 | 12.5 | |

Table 10 examines the relationship between parents identity in the transmission of sexual knowledge and whether students think that sex education is necessary in schools. According to the data, there was no necessary connection between the two, and most students believed that sex education was necessary at schools.

Our study's findings have implications for the teaching and learning of sexual knowledge. The results in Figure 1 show that the sources of students' knowledge about sexuality are not the same. At the personal level, individuals should take the initiative to learn scientific sexual knowledge, develop their personal growth, and understand sexual responsibility, particularly in preventing STDs from occurring. According to the results of Figure 8, the experimental results show that some parents are in a defensive role when their children are confused about sexuality. A small number of students do not tell their parents about deliberate verbal or behavioral teasing by others. At the parental level, the survey on college sex education reflects a lack of parental education in their role of laying a foundation of age-appropriate childhood sexual knowledge. When the child is young, parents should seize the opportunity for sex education. Eventually, the child becomes curious about the body; the more curious the child is, the more we want to address this curiosity, so that parents’ attitudes toward sex education is natural and sincere. As healthy children grow up, parental sex education can help them answer their children’s questions intuitively and interestingly. When parents educate their children about sex, they should not only emphasize protecting private parts and what cannot be done, but also share important values of equality, respect, reason, and emotion[25]. At the school level, schools provides teachers with financial support to carry out sex education courses based on sexual knowledge and legal ethics[26], with physiological and psychological changes as the core and practical and sustainable education as the purpose. The method and attitude of sexual knowledge dissemination should be age-appropriate, and others' perspectives should be considered to understand the feelings of college students, respect their personality differences, support individual privacy, and adhere to scientific and normative standards[27]. The experimental results show that in the current environment of China, there is still a situation of talking about "sexual" color change in society. However, there is still no way to disseminate sexual knowledge at the social level. At the social level, society should strengthen sex education, help citizens establish appropriate values, regularly carry out sex education-related activities, mobilize young people’s enthusiasm, appropriately and compassionately describe real cases of sexual assault, and teach young people measures to prevent sexual assault. When sexual assault occurs, rumors should not be spread or fabricated and must be treated with an inclusive attitude[28]. Psychology and sex education experts can be invited to speak regularly in the community to raise community awareness of sexual safety[29].

This study used undergraduate students majoring in medicine in medical colleges as research object, and considered their majors are special, so that they can draw corresponding conclusions in a more targeted manner. Additionally, post-2000s medical students were used as the research participants to explore the cognition of sex education, aiming to fill the gap in the literature with innovative studies of practical social value[30]. This focus differs from that of previous studies, as the questionnaire in this study provides a more comprehensive investigation of college students’ sex education, allowing for more extensive conclusions from a smaller number of questions. The questionnaire reflected a lack of parental involvement in their children’s sex education and provided reference values for contemporary parents in educating children. The results focus on the analysis of the relationship between sex and responsibility, and many college students have a weak awareness of sexual responsibility and cannot correctly restrain their behavior. They also point out that schools should focus on the implementation of responsibility education, and consider sexual morality and responsibility as the top priority of sex education. There are similar questions in the question set, and according to the answering situation, it can be determined whether the questionnaire results are reliable and whether the experimental results are authentic. Factors such as gender, region, and profession that may affect sexual cognition are comprehensively considered, and the data were analyzed using statistical software such as GraphPad Prism and SPSS; the results are comprehensive and reflect the actual problems[31].

The survey, which included one-sixth of undergraduate students, covered a wide range of topics and provided a true reflection on the real problems. College students continue to provide talent for the current national construction, and cultivating them with a sense of responsibility plays a significant positive role in the construction and development of the entire country. The social nature of sexuality and responsibility concerns not only the individual but also society as a whole. Through the survey, it is found that there are deviations in the research subjects’ cognition of sexual responsibility and sexual morality, and it is the general trend to establish a sound sexual ethics educational system, advocate adhering to the direct unity of sex and marriage, guide college students to form a healthy view of love, love, and family mate selection, and promote the formation of a healthy personality. Internationally, sex education outside of the Chinese context started earlier, and the relevant education system is perfect; however, there is still a lack of pertinence in the education of different groups of people. This survey took students from a medical school in China as the starting point to preliminarily understand the mastery of sexual knowledge among medical students, which can be more sex-only to formulate a relevant education system that has great social value.

This study has some limitations. The target population of the survey was limited to medical school students, and the study design was insufficient, resulting in a lack of universality. The questionnaire contained a few questions, and there was no relevant testing or analytical system. By expanding the sample to include medical students from various regions of China, the study captured a broader range of perceptions of sex education to eliminate regional differences. Additionally, research on international students’ views on related issues could facilitate a comparison of perspectives between domestic and foreign contexts, allowing for mutual learning. Continuous improvement of the questionnaires will contribute to the development of a more effective test system for surveying sexual knowledge. A nationwide census of college students, along with the optimization of a sex educational system tailored to the national context, could further enhance the research.

Sex education in China is still in its infancy, and problems such as a lack of effective management and supervision mechanisms and insufficient enforcement persist. The results of the survey showed that there was a deviation in the understanding of sexuality- related issues among the research participants, and relevant national departments must accelerate the pace of development and provide more effective development solutions. Based on the needs and current situation, it is necessary to conduct sex education for contemporary college students, medical schools, and all types of colleges and universities to strengthen scientific sex education for students.

| 1. | Goldfarb ES, Lieberman LD. Three Decades of Research: The Case for Comprehensive Sex Education. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68:13-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mark NDE, Wu LL. More comprehensive sex education reduced teen births: Quasi-experimental evidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lindberg LD, Maddow-Zimet I, Boonstra H. Changes in Adolescents' Receipt of Sex Education, 2006-2013. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58:621-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lameiras-Fernández M, Martínez-Román R, Carrera-Fernández MV, Rodríguez-Castro Y. Sex Education in the Spotlight: What Is Working? Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Haberland N, Rogow D. Sexuality education: emerging trends in evidence and practice. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:S15-S21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cook MA, Wynn LL. 'Safe sex': evaluation of sex education and sexual risk by young adults in Sydney. Cult Health Sex. 2021;23:1733-1747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fekadu Wakasa B, Oljira L, Demena M, Demissie Regassa L, Binu Daga W. Risky sexual behavior and associated factors among sexually experienced secondary school students in Guduru, Ethiopia. Prev Med Rep. 2021;23:101398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dodd S, Widnall E, Russell AE, Curtin EL, Simmonds R, Limmer M, Kidger J. School-based peer education interventions to improve health: a global systematic review of effectiveness. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:2247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Haberland NA. The case for addressing gender and power in sexuality and HIV education: a comprehensive review of evaluation studies. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2015;41:31-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Santelli JS, Kantor LM, Grilo SA, Speizer IS, Lindberg LD, Heitel J, Schalet AT, Lyon ME, Mason-Jones AJ, McGovern T, Heck CJ, Rogers J, Ott MA. Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage: An Updated Review of U.S. Policies and Programs and Their Impact. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61:273-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kantor LM, Lindberg LD, Tashkandi Y, Hirsch JS, Santelli JS. Sex Education: Broadening the Definition of Relevant Outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68:7-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Maziarz LN, Dake JA, Glassman T. Sex Education, Condom Access, and Contraceptive Referral in U.S. High Schools. J Sch Nurs. 2020;36:325-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Serra ME. Comprehensive sex education. The role of pediatricians. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2020;118:84-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Garg N, Volerman A. A National Analysis of State Policies on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning/Queer Inclusive Sex Education. J Sch Health. 2021;91:164-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sedgh G, Finer LB, Bankole A, Eilers MA, Singh S. Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: levels and recent trends. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:223-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 531] [Cited by in RCA: 485] [Article Influence: 48.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Osadolor UE, Amoo EO, Azuh DE, Mfonido-Abasi I, Washington CP, Ugbenu O. Exposure to Sex Education and Its Effects on Adolescent Sexual Behavior in Nigeria. J Environ Public Health. 2022;2022:3962011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Crowley G, Bandara P, Senarathna L, Malalagama A, Gunasekera S, Rajapakse T, Knipe D. Sex education and self-poisoning in Sri Lanka: an explorative analysis. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Garzón-Orjuela N, Samacá-Samacá D, Moreno-Chaparro J, Ballesteros-Cabrera MDP, Eslava-Schmalbach J. Effectiveness of Sex Education Interventions in Adolescents: An Overview. Compr Child Adolesc Nurs. 2021;44:15-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fowler LR, Schoen L, Smith HS, Morain SR. Sex Education on TikTok: A Content Analysis of Themes. Health Promot Pract. 2022;23:739-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Arakawa S. Education for prevention of STIs to young people (2021 version) Standardized slides in youth education for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections-for high school students and for junior high school students. J Infect Chemother. 2021;27:1375-1383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Adedini SA, Mobolaji JW, Alabi M, Fatusi AO. Changes in contraceptive and sexual behaviours among unmarried young people in Nigeria: Evidence from nationally representative surveys. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0246309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jiménez-Ríos FJ, González-Gijón G, Martínez-Heredia N, Amaro Agudo A. Sex Education and Comprehensive Health Education in the Future of Educational Professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rasmussen KR, Bierman A. Risk or Release?: Porn Use Trajectories and the Accumulation of Sexual Partners. Soc Curr. 2018;5:566-582. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Epps B, Markowski M, Cleaver K. A Rapid Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Consequences of Non-Inclusive Sex Education in UK Schools on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Questioning Young People. J Sch Nurs. 2023;39:87-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Paulauskaite L, Rivas C, Paris A, Totsika V. A systematic review of relationships and sex education outcomes for students with intellectual disability reported in the international literature. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2022;66:577-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | López González UA, Legaz Sánchez EM, Cárcamo Ibarra PM, Lluch Rodrigo JA. [Descriptive study about non-formal sex education resources available in Spain.]. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2023;97. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Sharma R. Vital Need for Sex Education in Indian Youth and Adolescents. Indian J Pediatr. 2020;87:255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Singh A, Both R, Philpott A. 'I tell them that sex is sweet at the right time' - A qualitative review of 'pleasure gaps and opportunities' in sexuality education programmes in Ghana and Kenya. Glob Public Health. 2021;16:788-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lo Moro G, Bert F, Cappelletti T, Elhadidy HSMA, Scaioli G, Siliquini R. Sex Education in Italy: An Overview of 15 Years of Projects in Primary and Secondary Schools. Arch Sex Behav. 2023;52:1653-1663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lindberg LD, Kantor LM. Adolescents' Receipt of Sex Education in a Nationally Representative Sample, 2011-2019. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70:290-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Atkins DN, Bradford WD. The Effect of State-Level Sex Education Policies on Youth Sexual Behaviors. Arch Sex Behav. 2021;50:2321-2333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |