Published online Apr 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.102267

Revised: January 19, 2025

Accepted: February 5, 2025

Published online: April 19, 2025

Processing time: 162 Days and 9.3 Hours

The study by Lu et al explores the integration of remote family psychological support courses (R-FPSC) with traditional caregiver-mediated interventions (CMI) in the context of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Conducted as a single-blinded randomized controlled trial involving 140 parents of children with ASD, the research highlights the crucial role of parental mental health in optimizing therapeutic outcomes. Results indicate that the addition of R-FPSC significantly enhances parental competence and reduces stress more effectively than CMI alone. Despite improvements in parenting stress and competence, no significant differences were noted in anxiety and depression symptoms between the groups, suggesting that while R-FPSC strengthens parenting skills, its impact on mood disorders requires further investigation. The findings advocate for the inclusion of remote psychological support in family interventions as a feasible and cost-effective strategy, broadening access to essential resources and improving both parental and child outcomes. The study emphasizes the need for future research to evaluate the long-term impacts of such interventions and to explore the specific mechanisms through which parental mental health improvements affect child development.

Core Tip: Lu et al's study demonstrates that integrating remote psychological support with traditional interventions for autism significantly boosts parental competence and reduces stress, although its effect on mood disorders is limited. This approach highlights the need for family-centered care and suggests that remote support can enhance autism care by providing accessible resources that benefit both parents and children.

- Citation: Byeon H. Enhancing autism care: The role of remote support in parental well-being and child development. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(4): 102267

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i4/102267.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.102267

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) presents a complex array of challenges not only for the individuals affected but also for their families, particularly parents who play a crucial role in the caregiving process. The study by Lu et al[1] on "Effects of remote support courses on parental mental health and child development in autism" provides significant insights into how integrating remote psychological support with traditional caregiver-mediated interventions (CMI) can positively impact both parental mental health and child development.

The examination of parental mental health within the caregiving process for children with ASD uncovers a critical component that shapes both the quality of care and consequential developmental outcomes for the affected children. It is well documented that the stress and demands inherent in raising a child with ASD can exert profound effects on parental well-being, thereby influencing the effectiveness and consistency of caregiving. According to the study by Benjak et al[2], parents of children with ASD consistently experience significantly higher levels of psychological stress and disorders compared to parents of non-disabled children, underscoring the importance of targeted support to improve parental welfare.

This bidirectional influence between parental mental health and child behavior is epitomized in studies demonstrating how parental stress and mental health conditions directly mediate the effectiveness of interventions for autism. Improvements in parental well-being not only mitigate stress but also enhance family adaptive functioning, thereby contributing to more favorable developmental trajectories for children with ASD[3]. Potential mediators such as psychological acceptance have also been identified, suggesting that fostering this trait among parents can aid in coping with the chronic challenges associated with ASD, consequently reducing psychological distress and enhancing caregiving efficacy[4].

The pervasive influence of parental mental health on caregiving experiences and child developmental outcomes has profound implications for intervention strategies. Theoretical models of caregiving within the context of ASD have consistently pointed to the critical need for integrating psychological support specifically tailored for parents into autism interventions. This approach rests on the rationale that interventions aimed directly at reducing parental anxiety and depression can create an environment conducive to improved therapeutic outcomes for children, thereby aligning with the broader frameworks advocating for holistic, family-centered approaches to autism care[5].

Ultimately, the dynamic interplay between parental mental health, caregiving processes, and child development in ASD not only underscores the necessity for comprehensive support systems for families but also illuminates pathways for enhancing intervention strategies. By fostering parental competence and stress management skills, the potential to achieve better long-term outcomes for children with ASD is significantly elevated, reinforcing the foundational need for psychosocial components within therapeutic paradigms.

CMIs have long been a pivotal component in the treatment paradigm for children with ASD, aiming to equip parents with the skills necessary to support their child's developmental needs effectively. These interventions have demonstrated capacity-building in parents, enhancing their engagement and competence and thereby improving child outcomes. However, despite their efficacy, traditional CMIs often fall short in addressing the mental health needs of the caregivers themselves, which is a critical determinant in sustainable caregiving practices[6].

This gap underscores the rationale for integrating remote family psychological support courses (R-FPSC) into the CMI framework. The R-FPSC approach leverages technological advancements to provide flexible, accessible psychological support to caregivers, alleviating barriers associated with traditional in-person interventions. As highlighted by Posch-Eliskases et al[7], offering knowledge, information, and training through digital platforms, such as the internet or telephone helplines, has proven effective in reducing caregiver stress and improving overall well-being.

The introduction of R-FPSCs represents an innovative advancement in supporting families of children with ASD. By providing emotional support and enhancing caregivers' mental health, these courses can significantly bolster the efficacy of CMIs. The remote element ensures wider reach, catering to families who may have limited access to traditional support services due to geographical or logistical constraints. This was particularly evident during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, where adaptations to online formats underscored the critical role of remote psychological interventions in maintaining caregivers' support networks and enhancing intervention outcomes[8].

The positive impact of these interventions is echoed in studies highlighting the benefits of psychological support for family caregivers. By reducing caregiver burden and improving coping skills, remote supports such as R-FPSCs amplify the benefits observed in conventional caregiver training programs and contribute to better overall caregiving experiences[9]. Such support mechanisms not only improve the immediate mental health and stress profiles of caregivers but also facilitate a more nurturing environment conducive to the developmental progress of children with ASD. Table 1 presents the results of a previous study[10-19] on the impact of R-FPSC on supporting families of children with ASD (Table 1).

| Ref. | Outcome measured | Key findings |

| Levante et al[10] | Parental stress | 30% reduction in stress |

| Kalb et al[11] | Parental anxiety | 25% reduction in anxiety |

| Huang et al[12] | Parenting knowledge | 40% improvement in ASD understanding |

| Efstratopoulou et al[13] | Communication strategies | Enhanced communication with children |

| Lei and Kantor[14] | Family dynamics | 35% reported improved family functioning |

| Viezel et al[15] | Family empathy | Increased empathy and support |

| Furar et al[16] | Child social engagement | 20% improvement in social skills |

| Bi et al[17] | Child behavioral issues | 15% reduction in behavioral concerns |

| McConkey et al[18] | Accessibility | 80% found remote format flexible |

| Srinivasan et al[19] | Participation barriers | Reduced travel and scheduling barriers |

In conclusion, R-FPSC offers a transformative approach to enhancing CMIs for ASD, addressing a critical gap in caregiver mental health support. As the landscape of therapeutic interventions continues to evolve, it remains imperative to integrate comprehensive support structures that focus on the holistic well-being of both caregivers and the children they support.

The integration of remote psychological support into family interventions reflects a significant evolution in digital health trends, in which telehealth and other remote solutions are increasingly being utilized to enhance the accessibility and efficiency of healthcare delivery. This shift has gained momentum as studies across various health contexts have consistently demonstrated the potential of remote support to mitigate barriers to care, such as geographic limitations and time constraints, thereby broadening the reach and impact of health interventions[20].

In the realm of ASD, the implementation of remote support mechanisms holds particular promise. It enables con

Furthermore, telehealth interventions provide a viable means for increasing parent participation in early autism interventions. By offering support that is both accessible and sustainable, these interventions enable parents to seamlessly integrate teachable moments into daily routines, thus promoting key developmental skills such as language and imitation in their children[22]. This aligns with the growing body of research advocating for holistic, family-centered care models, which emphasize the dual focus on improving the well-being of both the child and the caregivers.

The broader adoption of telehealth services also holds significant implications for underserved families, particularly those in rural or remote areas where access to conventional in-person services may be limited. Studies have illustrated the capacity of telehealth to provide equivalent quality of care to traditional services, thereby supporting optimal child development in ASD by ensuring that families receive timely and necessary intervention support from the convenience of their homes[23].

Ultimately, the integration of remote psychological support into ASD care frameworks exemplifies a progressive step towards more inclusive and effective healthcare delivery. By aligning with digital health innovations, such interventions are poised to enhance family dynamics, improve developmental outcomes for children with ASD, and foster a sustainable model of care that transcends the limitations of conventional approaches.

Lu et al's study employed a single-blinded randomized controlled trial design aimed at evaluating the impact of integrating R-FPSC with traditional CMI on parental mental health and child development in the context of ASD[1]. Conducted at the Department of Child Health Care, Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University in Chongqing City, China, the study took place from February to June 2023. The study recruited parents of 140 autistic children, randomly assigning them into two groups: The experimental group, which received R-FPSC in addition to CMI, and the control group, which only participated in CMI.

The sample size calculation was based on the total score of the parenting stress index-short form (PSI-SF), used as the main evaluation index. The experimental group consisted of 71 participants, while the control group had 69 participants. Key measures employed in the study included the PSI-SF for assessing parenting stress, the parenting sense of competence scale (PSOC) for evaluating parental competence, and both the generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) and patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for measuring anxiety and depression levels in parents. Children's development was assessed using the childhood autism rating scale and Gesell developmental schedules.

The intervention for the experimental group incorporated R-FPSC alongside CMI, which involved theory teaching videos and practical operation lessons delivered through the WeChat platform. These components were designed to provide both theoretical knowledge and practical skills to enhance the mental health of parents and promote better developmental outcomes for their children.

The study conducted by Lu et al[1] reveals significant insights into the effects of integrating R-FPSC with traditional CMI for parents of children with ASD. The primary outcomes highlighted a notable reduction in parenting stress in the experimental group compared to the control group (Table 2). The PSI-SF scores decreased significantly post-intervention, with the experimental group showing a reduction from 94.75 ± 20.95 to 81.10 ± 19.76, while the control group decreased from 96.99 ± 19.53 to 92.10 ± 19.26, indicating the effectiveness of R-FPSC in reducing stress levels (P < 0.01).

| Measure | Experimental group pre/post | Control group pre/post | P value |

| Parenting stress (PSI-SF) | 94.75 ± 20.95/81.10 ± 19.76 | 96.99 ± 19.53/92.10 ± 19.26 | < 0.01 |

| Parental competence (PSOC) | 59.38 ± 11.59/68.83 ± 11.23 | 61.48 ± 9.94/63.91 ± 10.86 | < 0.01 |

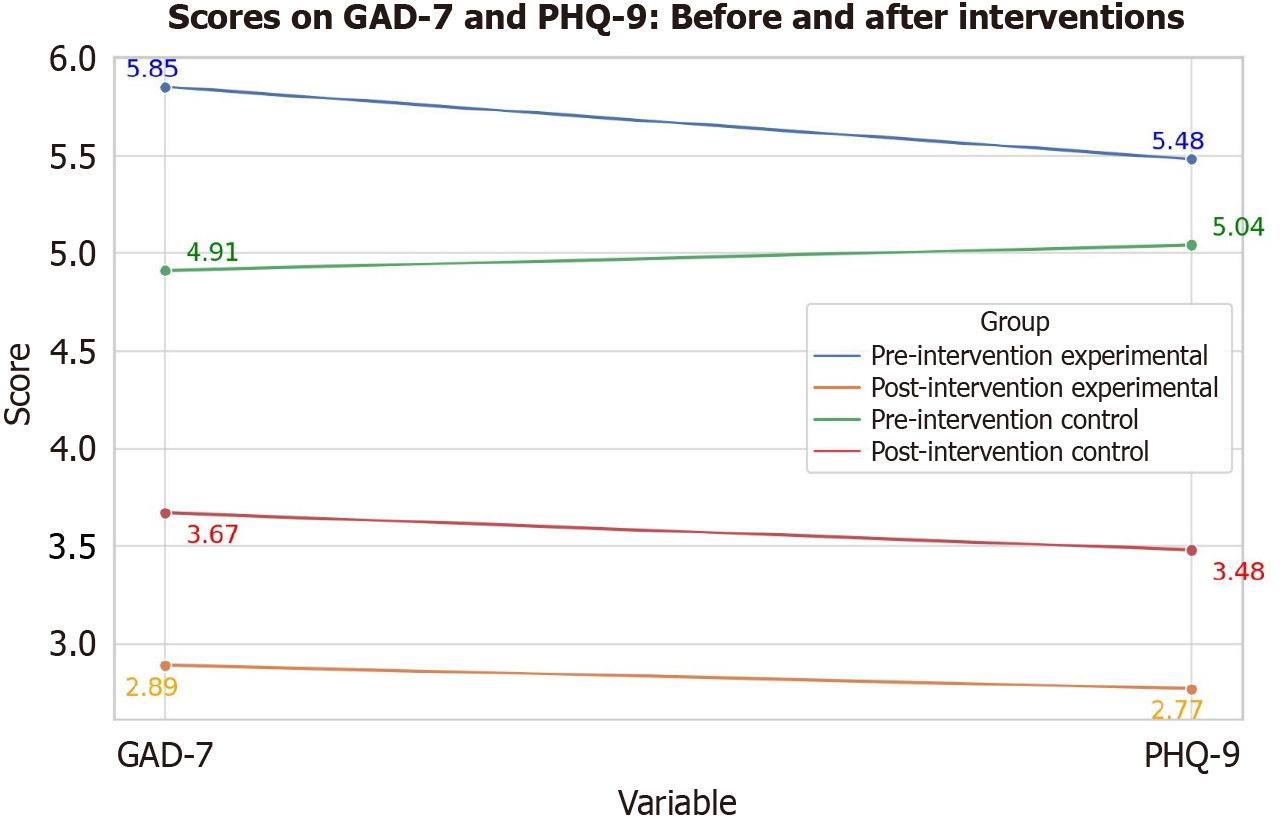

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | 5.85 ± 4.67/2.89 ± 3.19 | 4.91 ± 4.63/3.67 ± 3.92 | 0.238 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 5.48 ± 4.86/2.77 ± 3.00 | 5.04 ± 4.77/3.48 ± 4.27 | 0.594 |

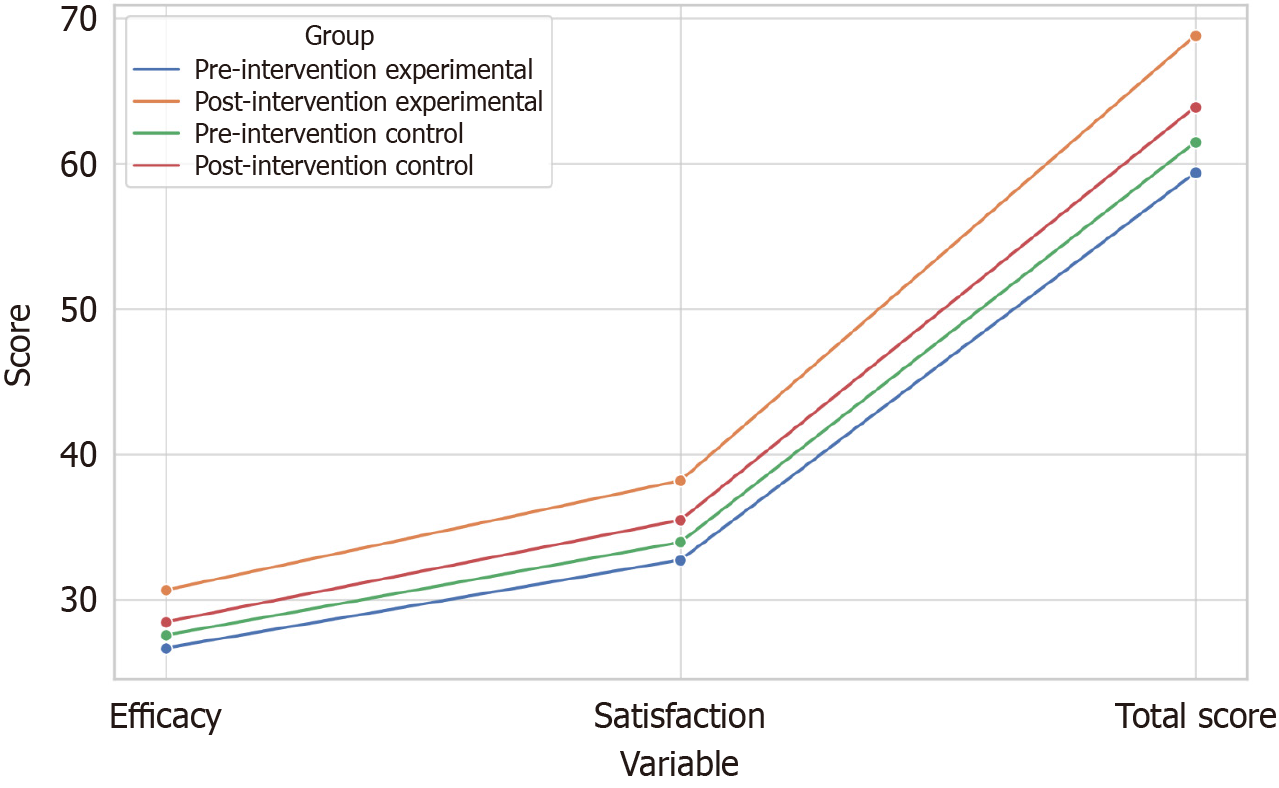

In terms of parental competence, measured by the PSOC scale, the results were also favorable for the experimental group (Figure 1). Post-intervention, the experimental group showed an increase in efficacy and satisfaction scores, rising from 59.38 ± 11.59 to 68.83 ± 11.23, compared to the control group’s increase from 61.48 ± 9.94 to 63.91 ± 10.86. These findings suggest that the R-FPSC significantly enhances the sense of competence among parents, contributing to their overall satisfaction and efficacy in parenting (P < 0.01).

Despite these improvements in stress and competence, the study found no significant differences in anxiety and depression reductions between the groups (Figure 2). Both groups showed a decrease in anxiety and depression scores as measured by the GAD-7 and PHQ-9, but the changes were similar across both groups, indicating that while R-FPSC effectively supports parental competence and stress reduction, it may not directly influence mood disorders (Table 2, Figures 1 and 2).

The integration of R-FPSC into autism care provides a multifaceted approach to addressing the challenges faced by parents of children with ASD. First, the integration of R-FPSC in autism care represents a practical approach to reducing parenting stress. By providing parents with accessible, remote resources, this intervention can significantly alleviate the psychological burden associated with caregiving for children with ASD. This reduction in stress can improve the quality of life for parents, which is crucial for sustaining their long-term involvement in therapeutic processes.

Second, the enhancement of parental competence through R-FPSC underscores the importance of empowering parents with skills and knowledge to better support their children. As parental competence increases, so does their ability to manage challenging behaviors and implement therapeutic strategies effectively. This empowerment can lead to better developmental outcomes for children with ASD, as parents become more confident and effective in their caregiving roles.

Third, although the study did not find significant changes in anxiety and depression scores, the overall improvements in parenting stress and competence suggest that targeted interventions for mood disorders might be needed. Clinicians should consider integrating additional psychological support specifically focused on addressing anxiety and depression, potentially through supplementary therapies or counseling.

Fourth, the study highlights the need for a holistic, family-centered approach in ASD interventions. By addressing both the psychological needs of parents and the developmental needs of children, healthcare providers can create a more supportive environment that fosters resilience and promotes positive outcomes. This approach encourages the development of comprehensive care models that consider the family unit as a whole, rather than focusing solely on the child.

Fifth, the findings advocate for the broader integration of technology in mental health services, particularly in reaching families who may face barriers to accessing traditional in-person support. Remote interventions like R-FPSC can bridge gaps in service delivery, offering flexible and scalable solutions that can be adapted to various settings and populations.

Sixth, to further optimize the content and format of remote support courses, future research should investigate personalized approaches that address the diverse needs of families. This could involve developing adaptive learning modules that adjust to the unique challenges and progress of each family. Incorporating interactive elements such as virtual support groups and real-time feedback mechanisms could enhance engagement and provide immediate assistance. Furthermore, leveraging data analytics to track parental progress and adapt content dynamically could ensure the ongoing relevance and effectiveness of the support. These innovations could lead to a more tailored and impactful intervention, ultimately improving the efficacy of remote psychological support in autism care.

Seventh, to enhance readability and provide practical insights, future studies could incorporate interviews with parents and professionals involved in the remote support program. Collecting relevant case reports can provide a narrative understanding of the real-world application and benefits of R-FPSC. For example, a case report could detail how a parent successfully integrated R-FPSC strategies into their daily routines, resulting in noticeable improvements in both their stress management and their child's developmental progress. Similarly, interviews with professionals could illuminate the program's implementation challenges and successes, offering valuable perspectives on how to optimize these courses for wider dissemination. By sharing these practical case studies, the article can offer readers a clearer, more relatable understanding of the program's impact and potential.

While the study provides valuable insights into the potential benefits of integrating R-FPSC with traditional CMIs, it is important to acknowledge several limitations that may affect the interpretation and generalization of the findings. First, the study's sample size, while adequate for initial findings, may limit the generalizability of the results. With only 140 participants, the study may not fully capture the diversity of experiences and outcomes that could occur in a larger, more varied population. Future research should aim to include a larger and more diverse sample to enhance the robustness and applicability of the findings.

Second, the relatively short duration of the intervention and follow-up period may not fully reflect the long-term effects of integrating R-FPSC with traditional CMIs. Longitudinal studies are necessary to understand the sustained impact of these interventions on both parental mental health and child development over time.

Third, while the study effectively measures changes in parental stress and competence, it does not adequately address other potential variables that might influence these outcomes, such as socio-economic status, access to additional support systems, or cultural differences. These factors could significantly impact the effectiveness of the intervention and should be considered in future research.

Fourth, the study's reliance on self-reported measures may introduce bias, as participants might underreport or overreport their stress levels and sense of competence. Incorporating objective measures or third-party assessments could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the intervention's impact.

Fifth, the study did not find significant changes in anxiety and depression scores, which suggests that the R-FPSC intervention may not fully address these aspects of parental mental health. Further research should explore additional or complementary interventions that specifically target anxiety and depression to provide a more comprehensive support system for parents. Incorporating these additional insights and addressing the noted gaps will be crucial for refining intervention strategies and enhancing their effectiveness and relevance across diverse contexts.

Lu et al's research[1] provides a promising direction for enhancing autism care through the inclusion of remote psychological support. By focusing on parental mental health, this approach not only supports caregivers but also indirectly benefits the children they care for. As we continue to seek effective interventions for ASD, the integration of remote support systems represents a progressive step towards more holistic, accessible, and family-centered care models.

| 1. | Lu JH, Wei H, Zhang Y, Fei F, Huang HY, Dong QJ, Chen J, Ao DQ, Chen L, Li TY, Li Y, Dai Y. Effects of remote support courses on parental mental health and child development in autism: A randomized controlled trial. World J Psychiatry. 2024;14:1892-1904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Benjak T, Vuletić Mavrinac G, Pavić Simetin I. Comparative study on self-perceived health of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders and parents of non-disabled children in Croatia. Croat Med J. 2009;50:403-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Estes A, Swain DM, MacDuffie KE. The effects of early autism intervention on parents and family adaptive functioning. Pediatr Med. 2019;2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Weiss JA, Cappadocia MC, MacMullin JA, Viecili M, Lunsky Y. The impact of child problem behaviors of children with ASD on parent mental health: the mediating role of acceptance and empowerment. Autism. 2012;16:261-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Likhitweerawong N, Boonchooduang N, Louthrenoo O. Parenting Styles, Parental Stress, and Quality of Life Among Caregivers of Thai Children with Autism. Int J Disabil Dev Educ. 2022;69:2094-2107. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Foster K. 'I wanted to learn how to heal my heart': family carer experiences of receiving an emotional support service in the Well Ways programme. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2011;20:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Posch-eliskases U, Rungg C, Moosbrugger M, Perkhofer S. Supporting Family Cargivers / Unterstützung für pflegende Angehörige. Int J Health Prof. 2015;2:31-37. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Foroughe M, Soliman J, Bean B, Thambipillai P, Benyamin V. Therapist adaptations for online caregiver emotion-focused family therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Person-Centered Experiential Psychotherapies. 2022;21:1-15. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Smith Barusch A, Spaid WM. Reducing Caregiver Burden Through Short-Term Training: Evaluation Findings from a Caregiver Support Project. J Gerontol Soc Work. 1991;17:7-33. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Levante A, Petrocchi S, Bianco F, Castelli I, Colombi C, Keller R, Narzisi A, Masi G, Lecciso F. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Typically Developing Peers: An Online Survey. Brain Sci. 2021;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kalb LG, Badillo-Goicoechea E, Holingue C, Riehm KE, Thrul J, Stuart EA, Smail EJ, Law K, White-Lehman C, Fallin D. Psychological distress among caregivers raising a child with autism spectrum disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. Autism Res. 2021;14:2183-2188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huang S, Sun T, Zhu Y, Song S, Zhang J, Huang L, Chen Q, Peng G, Zhao D, Yu H, Jing J. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children with ASD and Their Families: An Online Survey in China. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:289-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Efstratopoulou M, Sofologi M, Giannoglou S, Bonti E. Parental Stress and Children's Self-Regulation Problems in Families with Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). J Intell. 2022;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lei X, Kantor J. Social support and family quality of life in Chinese families of children with autism spectrum disorder: the mediating role of family cohesion and adaptability. Int J Dev Disabil. 2022;68:454-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Viezel KD, Williams E, Dotson WH. College-Based Support Programs for Students With Autism. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl. 2020;35:234-245. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Furar E, Wang F, Durocher JS, Ahn YA, Memis I, Cavalcante L, Klahr L, Samson AC, Van Herwegen J, Dukes D, Alessandri M, Mittal R, Eshraghi AA. The impact of COVID-19 on individuals with ASD in the US: Parent perspectives on social and support concerns. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0270845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bi XB, He HZ, Lin HY, Fan XZ. Influence of Social Support Network and Perceived Social Support on the Subjective Wellbeing of Mothers of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Psychol. 2022;13:835110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mcconkey R, Mullan A, Addis J. Promoting the social inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorders in community groups. Early Child Dev Care. 2012;182:827-835. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Srinivasan S, Ekbladh A, Freedman B, Bhat A. Needs assessment in unmet healthcare and family support services: A survey of caregivers of children and youth with autism spectrum disorder in Delaware. Autism Res. 2021;14:1736-1758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McConkey R, Cassin MT, McNaughton R. Promoting the Social Inclusion of Children with ASD: A Family-Centred Intervention. Brain Sci. 2020;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cleffi C, Su WC, Srinivasan S, Bhat A. Using Telehealth to Conduct Family-Centered, Movement Intervention Research in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2022;34:246-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vismara LA, Young GS, Rogers SJ. Telehealth for expanding the reach of early autism training to parents. Autism Res Treat. 2012;2012:121878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hladik L, St John B, Carbery M, Gray M, Drew JR Jr, Ausderau KK. Benefits and Challenges of a Telehealth Eating and Mealtime Intervention for Autistic Children: Occupational Therapy Practitioners' Perspectives. OTJR (Thorofare N J). 2023;43:540-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |