INTRODUCTION

The rapidly aging global population has contributed to a significant increase in the prevalence of dementia, which is one of the most pressing health burdens worldwide[1,2]. Early identification of individuals at high risk of dementia and implementation of effective interventions are crucial components of prevention strategies[3,4]. Emerging research indicates that many elderly individuals exhibit slowing of gait prior to dementia diagnosis, which is closely associated with cognitive decline and can predict the risk of developing dementia. Annually, approximately 30% of the global population aged 65 and older experiences at least one fall, with the incidence increasing to 50% among those aged 85 and above[5]. Effective fall prevention in older adults fundamentally depends on the accurate identification and management of relevant risk factors.

Motoric cognitive risk syndrome (MCR), first proposed by Verghese et al[6] in 2014, is a pre-dementia condition. MCR provides a significant advantage in identifying individuals at high risk for dementia, as it can be readily assessed through subjective and objective methods, bypassing the need for lengthy neuropsychological evaluations and other time-consuming tests[7,8]. The study found that the overall prevalence of MCR was approximately 9.7%. In China, the prevalence of MCR among elderly women over 65 years old is approximately 12.6%, and it is approximately 12.8% in men [9]. A study conducted in three urban districts of Beijing showed that the prevalence of MCR in community-dwelling elderly people aged > 55 years was approximately 9.6%[10]. In Japan, a study involving nearly 10000 elderly individuals reported an MCR prevalence of 6.4%, ranging from 5.3% to 8.9%, indicating an increase in prevalence with age[11]. MCR not only serves as a prognostic indicator of dementia but is also associated with an elevated risk of falls, disability, and mortality. Yang et al[12] showed that the incidence of MCR is high among elderly individuals with subjective cognitive decline in China. Factors influencing the occurrence of MCR include age, the ability to perform activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, weekly exercise duration, anxiety status, hypertension, stroke, and transient ischemic attacks. Furthermore, existing studies have shown that the prevalence of MCR and its associated risk factors vary across different populations, which may be related to lifestyle and health beliefs[13]. Early screening and targeted interventions for MCR and its distinct subtypes can attenuate the progression of dementia and are critical for fall prevention[14].

However, there is a paucity of research examining MCR as a focal point for an in-depth exploration of fall prevention and management in the elderly population. This review analyzes the current status and causes of MCR-related falls, evaluates risk assessment methods and health management strategies associated with MCR, and aims to provide a theoretical foundation for promoting targeted fall prevention in community-dwelling elderly populations.

LITERATURE SEARCH

A comprehensive literature search was conducted from April 2023 to October 2024 using PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane Library. Our search strategy was designed to pinpoint studies related to "falls" and "MCR syndrome" by incorporating a variety of synonyms. Keywords related to "falls" include "falls" "slipping", "sliding", and "falling". Keywords related to "MCR" include "Motoric Cognitive Risk Syndrome", "motor cognitive risk", "cognitive motor risk", and "cognitive impairment". We refined the search strategy by incorporating Boolean operators (AND, OR, and NOT) to target specific subtopics within MCR and fall risk more effectively. To refine our search and exclude irrelevant content, we employed the NOT operator for terms such as "accidental falls" and to eliminate unrelated concepts like "financial falls". We utilized the AND operator to link "motoric cognitive risk syndrome" with related terms for cognitive impairment and motoric dysfunction, ensuring high relevance in our search results. The OR operator was used to encompass synonymous terms, allowing for a broader yet focused search (e.g., "falls" OR "falling" OR "slip and fall" OR "fall and slip"). The search was limited to articles published until October 2024. Additionally, we manually searched the reference lists of the identified articles to ensure a comprehensive collection of relevant literature.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Publicly published studies that investigated the relationship between MCR and falls; (2) Studies on the bio-psychosocial mechanisms of falls associated with MCR; and (3) Clinical trials, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses related to falls in the context of MCR. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Articles written in languages other than English or Chinese; (2) Duplicate publications; and (3) Case reports, clinical trial protocols, conference papers, letters, etc.

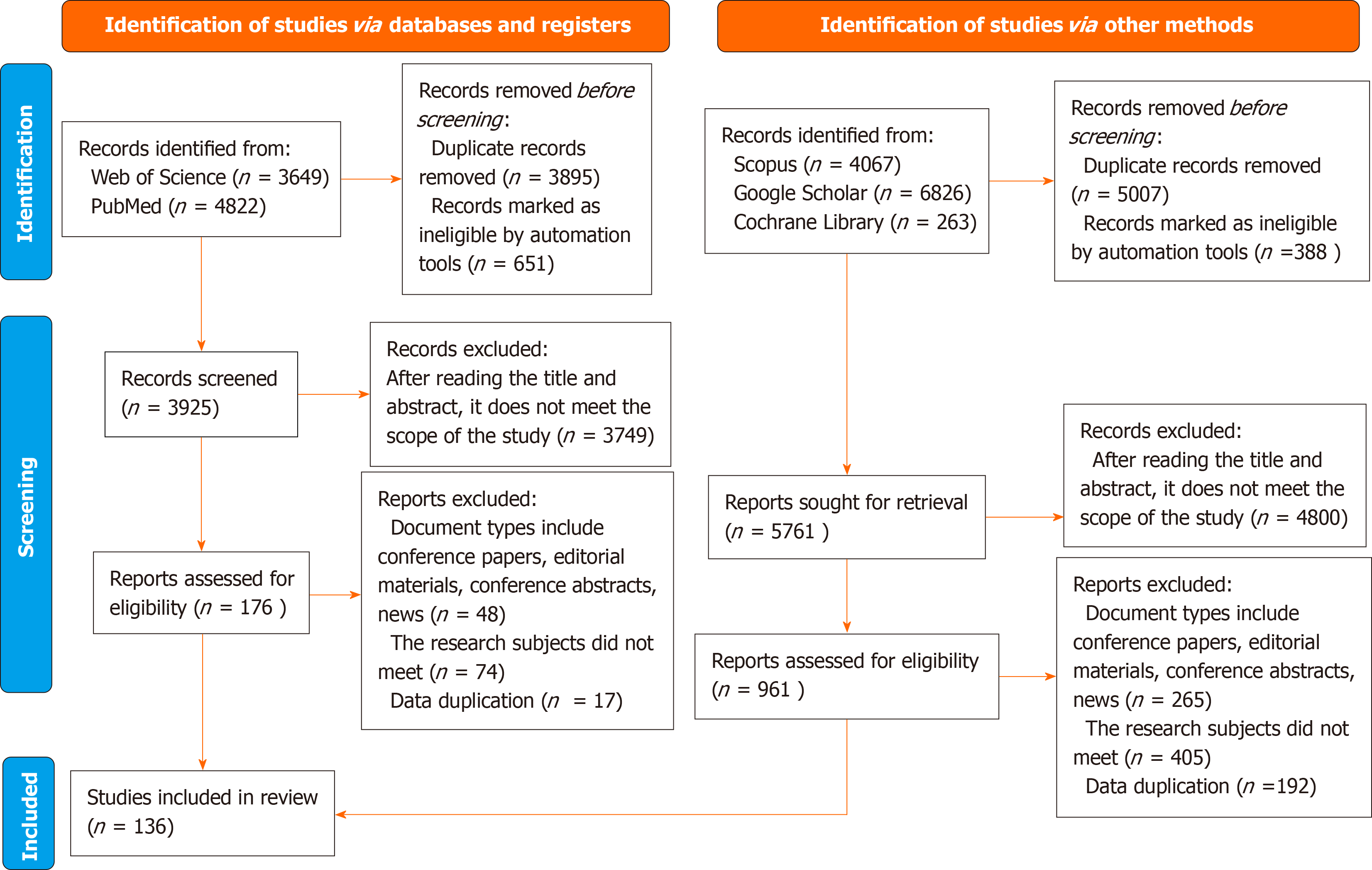

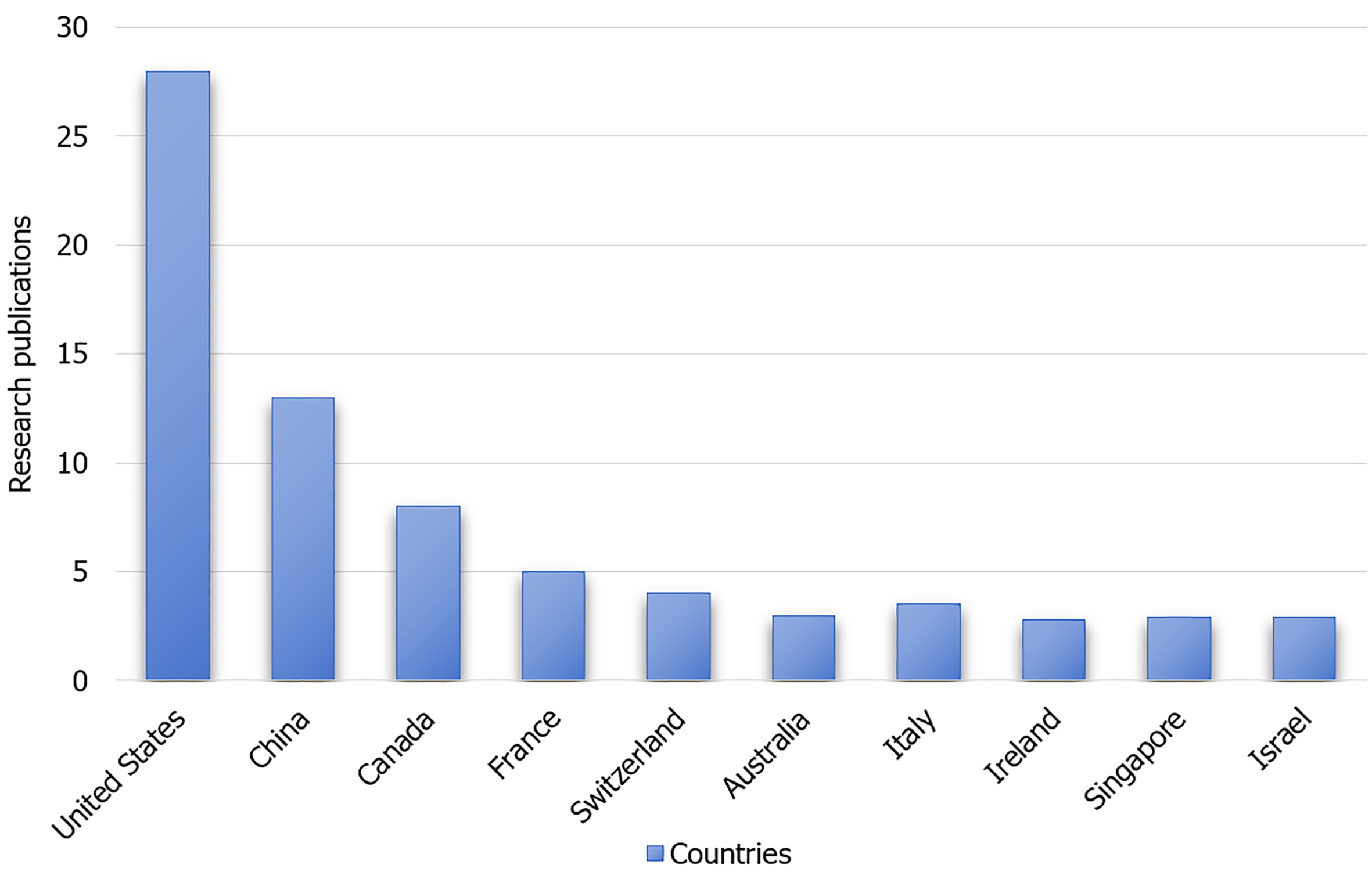

The initial search yielded 19627 articles. After reviewing the titles and abstracts and applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, irrelevant articles were excluded. Full-text screening of the remaining articles resulted in the inclusion of 136 relevant articles. The included studies were of high quality, with clear research objectives, well-defined methodologies, and results. The literature search and selection processes are shown in Figure 1. The top ten contributing countries in terms of publication volume are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1 PRISMA flow diagram for included studies in the review.

Figure 2 Top 10 countries in terms of motoric cognitive risk syndrome research publications.

THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN MCR AND FALLS

Falls are the third leading cause of death from unintentional injuries worldwide and significantly contribute to disability-adjusted life years lost due to injuries among the elderly population[15]. Falls can result in adverse outcomes, including fractures, hospitalization, and death in severe cases [16]. The long-term effects of falls include the development of fear of falling, subsequent loss of mobility, and increased need for self-care assistance[17]. Implementing accurate screening and targeted interventions for individuals at a high risk of falls is an essential goal in geriatric care. Lord et al[18] modeled gait and cognitive trajectories in the elderly population of New Zealand and identified clusters using latent class analysis. They employed a generalized linear model to examine the relationships among gait, cognition, MCR, and falls, revealing that Māori men were more likely to fall [OR = 1.56, 95%CI (1.00, 2.43)]. Additionally, non-Māori individuals with slow gait (SG) exhibited an increased risk of falling [OR = 0.40, 95%CI (0.24, 0.68)], while non-Māori individuals with MCR were more than twice as likely to fall compared to those without MCR [OR = 2.45, 95%CI (1.06, 5.68)]. This finding may be attributed to the combined effects of SG speed and subjective cognitive complaints (SCCs), which are the key components of MCR. In contrast, Callisaya et al[19] randomly selected 412 individuals aged 60-86 years from the Tasmanian electoral roll to investigate the relationship between gait and gait variability measurements and the risk of accidental falls. Logistic regression was used to estimate the relative risk of single and multiple falls based on gait measurements, and it demonstrated that greater individual variability in stride length and double support time was linearly associated with an increased risk of multiple falls. In addition, gait speed, cadence, and temporal gait variability exhibited nonlinear relationships with multiple falls. This suggests that gait variability rather than MCR itself may play a more significant role in fall risk in some individuals. Beauchet et al[20] explored the relationship between MCR and its components (SG speed and SCC) in community-dwelling elderly individuals, focusing on the occurrence, recurrence, and post-fall fracture risk. Results indicated that residents with MCR had a higher incidence of hip fractures than other residents. Cox regression analysis revealed that individuals with MCR had a significantly increased risk of falling (HR = 1.22), recurrent falls (HR = 1.46), and hip fractures following a fall (HR = 2.54). The conflicting findings across these studies could be due to differences in sample characteristics such as age, sex, and comorbidities, as well as variations in the study design and statistical methods.

Mechanisms of falls associated with MCR

Falls in individuals with MCR result from a complex interplay of factors, as outlined by the fall attribution model[15]. A comprehensive literature review identified key mechanisms, including the physiological, cognitive, and integrated effects of biological, psychological, and social factors.

Physiological mechanisms

One of the significant physiological mechanisms underlying falls in patients with MCR is the attenuation of muscle strength. With advancing age, older individuals experience a gradual decline in muscle mass and strength, leading to impaired standing stability and walking ability[16,17]. Especially in the lower limbs, the weakening of key muscle groups, such as the quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf muscles, makes it difficult for the elderly to maintain balance while walking and standing. Furthermore, the disuse atrophy of the muscles that may be present in patients with MCR exacerbates the decline in muscle strength, thereby increasing the risk of falls[18,21].

Decreased balance is another significant physiological mechanism contributing to falls in patients with MCR. Balance is a complex physiological process that involves the synergistic action of multiple systems, including vision, vestibular sensation, and proprioception[22]. Research indicates that degenerative changes in the nervous system can lead to balance issues, thereby increasing the risk of falls[23]. Skeletal muscle tissues and joints play crucial roles in controlling organ movements and maintaining balance. As age progresses, the loss of the vastus lateralis and overall muscle strength significantly increases the likelihood of falls, imbalance, and impaired motor function[24]. The central nervous system is responsible for coordinating overall sensory information, generating signals required for motor skills and reflexes and integrating cognition with postural control[25]. The cholinergic system is closely linked to cognitive function, balance control, and motor output through the regulation of acetylcholine levels and acetylcholinesterase activity. Patients with MCR may experience a decline in vision, vestibular function impairment, and proprioceptive disorders, which collectively affect balance. These issues make it more likely for older adults to lose balance while walking and standing, thereby increasing their risk of falls[26].

Cognitive mechanisms

Cognitive decline is a core symptom of MCR, and its impact on the risk of falls cannot be overlooked. Cognitive decline may lead to the inability of patients to effectively process environmental information during walking, such as ground conditions and obstacle locations, thereby increasing the risk of falls[27]. Additionally, memory impairment may cause patients to forget to use assistive devices or fail to adhere to exercise plans, further increasing the risk of falls. Attentional distraction is also an important manifestation of cognitive decline that may prevent patients from focusing during walking, thereby failing to perceive and respond to potential hazards[19].

Gait disturbances are another significant characteristic of patients with MCR, and their impact on fall risk is equally important[20,28]. Gait disturbances may manifest as a reduced walking speed, unsteady gait, and decreased stride length, all of which can increase the risk of falls[19]. A slow walking speed may prevent patients from reacting quickly to emergency situations, thereby increasing the likelihood of falling. An unsteady gait may lead to a loss of balance during walking, resulting in falls. Decreased stride length may restrict a patient's range of motion, increasing the risk of falling into confined spaces[29]. Furthermore, gait disturbances may trigger anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients, which can further affect their walking ability and increase their risk of falls[30].

Cognitive decline and gait disturbances are often intertwined and mutually influential in patients with MCR and share common biological mechanisms[7]. The interconnection between gait and cognition is primarily mediated by several core neuroanatomical regions, including the prefrontal cortex, supplementary motor area, insula, cerebellum, and basal ganglia[31]. The prefrontal cortex plays a pivotal role in executive function and cognitive control, particularly during gait planning and adjustment, with a significant increase in activity levels. The supplementary motor area is closely associated with motor planning and coordination, particularly in the execution of complex movements and integration of cognitive tasks[32]. The insula, which is primarily associated with emotional regulation and viscerosensory perception, plays a significant role in cognitive control and attentional focus, and its atrophy is associated with the development of MCR. The cerebellum plays a central role in motor coordination and learning, and its grey matter volume is closely associated with gait performance and executive function. On the other hand, the basal ganglia contribute to motor control and cognitive processes, particularly in movement planning and execution [33]. Collectively, these regions modulate motor control, cognitive function, and emotional responses, thereby forming a network of interactions between gait and cognition.

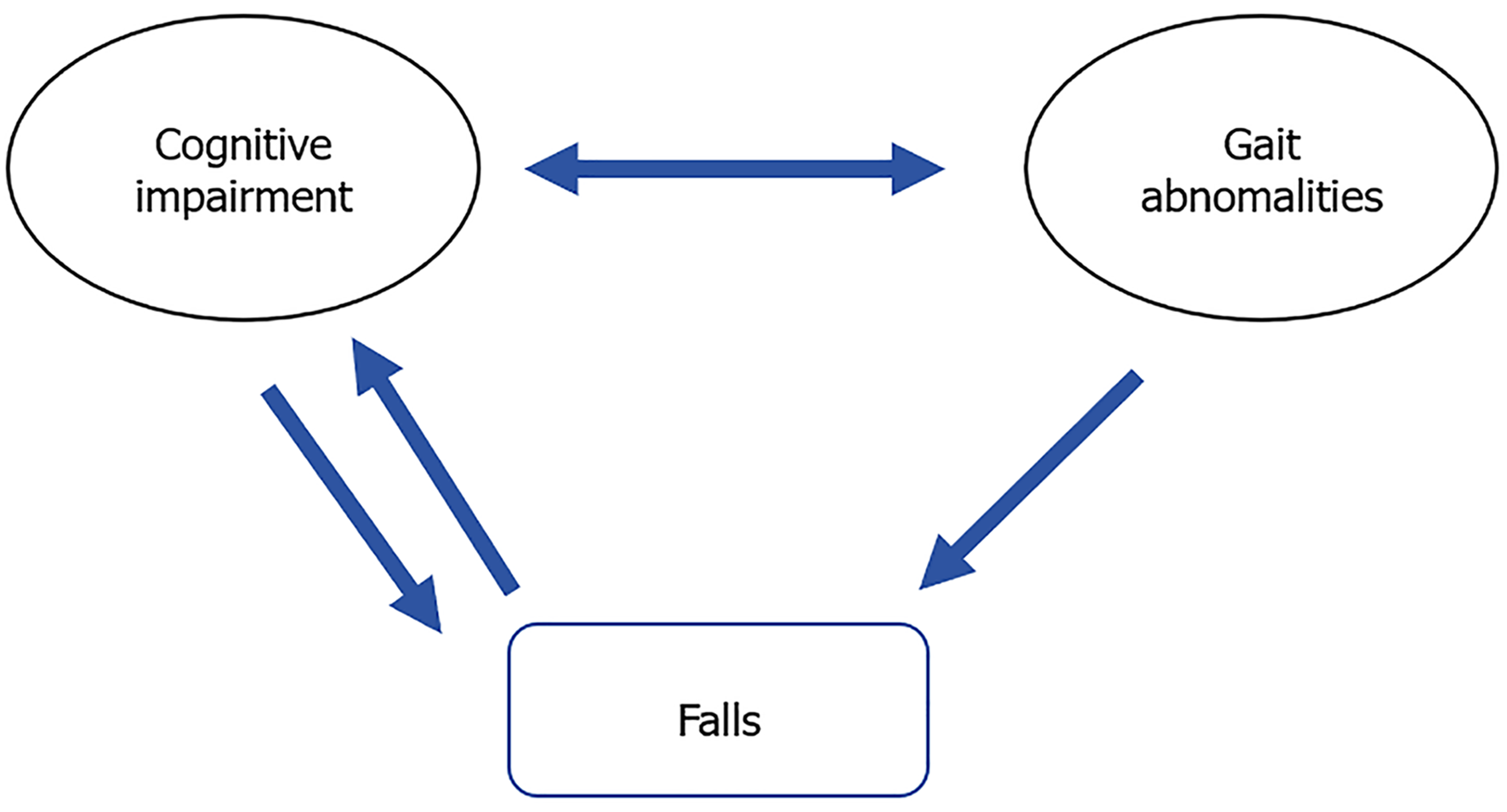

In summary, cognitive decline may exacerbate the severity of gait disturbances, making patients more susceptible to falls, and may also worsen cognitive decline, creating a vicious cycle (Figure 3)[34]. This interaction may significantly increase the risk of falls in patients with MCR and severely affect their quality of life. Therefore, a profound understanding of these mechanisms is crucial for developing interventions aimed at reducing cognitive and motor functions in the elderly.

Figure 3 The relationship between cognitive impairment, gait abnormalities, and falls.

The integrated effects of biological-psychological-social factors

Advanced age, cognitive impairment, structural changes in the brain, cardiovascular risk factors (such as diabetes and obesity), and hypertension are known risk factors for falls. Medical conditions, particularly diabetes, hypertension, and stroke, are prevalent in individuals with MCR, with 70% having at least two chronic diseases[35,36]. Diabetes can lead to muscle atrophy and neuropathy, which can affect gait stability[37]. Hypertension is often associated with cerebral arteriosclerosis and can cause ischemia and gait instability[36]. Polypharmacy is common in individuals with MCR and may increase the risk of falls through medication interactions[38,39]. Furthermore, research has indicated that elderly individuals experiencing interfering pain are at higher risk of developing MCR. Pain interference impairs cognitive functions such as attention, executive function, and memory, reduces the ability of the elderly to respond to environmental changes and potential hazards, and induces structural and functional alterations in the prefrontal cortex. These effects further weaken gait control and postural stability, significantly increasing the risk of falls[40]. Recent studies have shown that although overall poor sleep quality is associated with the occurrence of MCR, daytime dysfunction caused by sleep problems (such as excessive daytime sleepiness and reduced enthusiasm) significantly increases the risk of MCR. However, no significant correlation has been found between sleep quality and the severity of existing MCR[41].

Psychological factors, such as depression, fear of falling, neuroticism, and perceived stress also contribute to fall risk. Depression can double the risk of falls in the elderly[42], and individuals with MCR often have depressive symptoms that impair attention and coordination[43]. Furthermore, high levels of perceived stress are significantly associated with the risk of developing MCR syndrome, further increasing the likelihood of falls in older adults[44]. Fear of falling can limit activity, leading to a decline in muscle strength and balance and perpetuating a cycle of fear and falls[45].

Environmental factors significantly influence fall risk in individuals with MCR. Home hazards, such as a poor layout, inadequate lighting, and uneven surfaces, can pose particular dangers to those with limited mobility and balance[46,47]. Regarding the factor of "insufficient lighting", we recommend installing adequately bright lighting fixtures in the activity areas of older adults and using night lights at night to ensure that the illumination is sufficient and gentle. For "unreasonable furniture layout", it is suggested that furniture is rearranged to ensure that pathways are spacious and unobstructed, and that the height of the furniture is moderate, facilitating its use by older adults. In addition, measures such as applying anti-slip treatments to flooring and installing handrails in bathrooms can be implemented to prevent falls among older adults[48]. Social support is also crucial; community and family engagement can reduce anxiety and depression, thereby lowering the risk[49]. Integrating environmental risk assessments into geriatric care can help identify and address modifiable factors, and promote a safer environment for individuals[50].

ASSESSMENT METHODS FOR MCR-RELATED FALL RISK

The key criteria for diagnosing MCR are the presence of SCC and a SG[51]. Elderly individuals may perceive changes in their cognitive abilities or walking patterns before developing objective cognitive or motor impairments.

Assessment methods for SCC

Utilizing standardized assessment questionnaires for neuropsychological evaluation is an effective method for assessing the decline in subjective memory function in patients with MCR. Commonly used questionnaires include relevant items from the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale and AD8 Memory Impairment Self-Assessment Scale[52]. Items in these questionnaires, such as "Do you feel your memory is worse than most people?" or "Are you having problems with your everyday memory and thinking abilities?" reflects a decline in the patient's subjective memory function. If a patient's response indicates a significant decline in memory, it may imply a higher risk of falls because memory impairment could affect the patient's perception and judgment of the environment, thereby increasing the likelihood of falling.

Additionally, direct use of fall-related scales, such as the Self-rated Fall Risk Questionnaire (FRQ)[53] and the Falls Risk for Older People in the Community Screening Tool (FROP-Com)[54], can be employed to assess a patient's condition and determine the risk of falls. The FRQ, developed by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, evaluates fall risk in older adults living in the community, focusing on disease, medication, mental health, and physical fitness. Turanoglu and Sertel[54] demonstrated that a FRQ effectively distinguished frail and non-frail older adults, with frail individuals exhibiting significantly higher fall risk scores. The FROP-Com was developed by the Australian National Aging Research Institute. This scale is widely used to screen for fall risk in community-dwelling elderly populations[54]. Wickins et al[55] highlighted the importance of the FROP-Com as a key instrument for identifying fall risks among older adults in the emergency department. These scales are based on judgments made through evaluator observations, inquiries, and self-reports from the participants. Therefore, they are susceptible to subjective experience and recall bias, limiting the accuracy and objectivity of the measurements.

Assessment methods for SG

Gait assessment methods play a significant role in evaluating fall risk in patients with MCR. Commonly used gait assessment methods include gait parameters, walking speed, and dual-task walking tests, among others[56]. Verghese et al[6] found that a decrease of 10 cm/s in gait speed increased the risk of falls by 7%, with a SG being associated with a 1.5 times higher risk. Research indicates that factors such as stride length, standing time difference, and average stride time are closely related to the risk of falls. By collecting these gait data, predictive models can be established to assess the fall risk[57]. Pradhan et al[58] found that Gait Parameter-Based Fall Risk Assessment, which utilizes biomechanical parameters such as ground reaction force, center of pressure, and plantar pressure, achieved an 86.02% accuracy in classifying elderly fallers. Modern gait analysis systems such as wearable sensors and infrared technology can sensitively detect gait parameter issues and promptly identify gait abnormalities, thereby assessing fall risk. These systems can provide personalized gait function training programs to improve gait and reduce the risk of falls[59]. In clinical applications, combining multiple assessment tools, such as the Tinetti Balance and Gait Scale and Timed Up and Go Test, for a comprehensive evaluation can enhance the accuracy of fall risk assessments. However, it is highly recommended to not rely solely on one tool but to use a combination of various tools for a thorough evaluation. The assessment of gait parameters presents several challenges. For instance, it typically relies on specific equipment and environmental conditions, and a gait analysis conducted in a laboratory setting may not fully reflect the gait performance of older adults in their daily lives. When implementing gait parameter assessments in community or home environments, challenges, such as high equipment costs and complex operations, may arise, affecting their widespread application.

Dual-task walking, which combines cognitive tasks with walking, challenges postural stability in individuals with cognitive impairment and increases the risk of falls[60]. This method provides an objective assessment of cognitive functional impairments that are particularly relevant for individuals with MCR and cognitive and motor deficits. Udina et al[61] used functional near-infrared spectroscopy to demonstrate that individuals with MCR have increased frontal cortex activation during dual-task walking, which may compromise gait performance and increase fall risk[62]. However, this study's focus on gait speed overlooked other gait parameters. Future research should comprehensively examine gait characteristics and neurobiological mechanisms in MCR populations during dual-task conditions to enhance fall risk assessments. The dual-task walking test is a method for assessing an individual's ability to simultaneously perform motor and cognitive tasks, typically conducted in a quiet and obstacle-free environment. The single-task walking test is performed as follows: The time taken by the participants to walk at a normal pace from the starting line to the finish line was recorded, typically over a distance of 3 or 10 m. The dual-task walking test is performed as follows: While the participants were walking, they were required to complete a cognitive task, such as backward counting (starting from 100 and subtracting 7 each time) or a naming task (listing as many animal names as possible), and the time taken by the participants to complete the dual task was recorded. The scoring criteria included the walking speed and dual-task costs. Walking speed refers to the ratio of distance to time, whereas the dual-task cost is used to quantify the degree of decline in the participants' walking performance when executing dual tasks. The calculation formula was as follows: DTC = (dual-task time - single-task time)/single-task time × 100%. A high DTC indicates a significant decline in walking ability when performing dual tasks, suggesting a higher risk of falls. In addition, poor cognitive task performance may indicate cognitive impairment. By integrating these indicators, targeted intervention recommendations, such as enhancing balance or cognitive training, can be provided for individuals to improve their performance in complex situations and reduce the risk of falls. Executive function, which is essential for autonomous decision-making and ambulation, is compromised in multi-criticality individuals, thereby increasing the risk of falls. Incorporating executive function assessments into fall risk evaluations can facilitate early detection of vulnerable individuals with MCR. Falk et al[63] demonstrated that among physically active older adults, cognitive functions significantly explain gait speed and step length during normal and dual-task walking but not postural sway in a quiet stance. Executive function assessments are mostly cognitive tests that may be influenced by factors such as education level and language ability of older adults, leading to significant individual differences in assessment results. In different cultural contexts, the standardization and adaptability of executive function assessment tools present challenges that require cultural adaptation to ensure their effectiveness. Current executive function measurements, which often focus on single aspects, such as the Stroop or Trail Making tests, should be broadened to include comprehensive assessments to enhance the accuracy of fall risk prediction among MCR populations.

MANAGEMENT FOR MCR-RELATED FALLS

Health education, exercise, and nutritional interventions

Effective health education can prevent cognitive decline in older adults and help them understand their health development trajectory, as well as the factors influencing MCR-related falls. This knowledge can promote healthier lifestyles and improve physical and cognitive functions. Uemura et al[64] explored the impact of health education based on an active learning program on health literacy, cognitive function, physical activity, and dietary habits in older adults. In their study, 84 elderly individuals were randomly assigned to either the health education or control group. The health education group participated in a 24-week active learning program focused on exercise, diet, nutrition, and cognitive activities to promote health among older adults, whereas the control group received no intervention. The health education group were recommended the following: older adults should engage in at least 3-5 sessions of moderate-intensity exercise per week, lasting 30-60 minutes each. This can include aerobic activities such as brisk walking, swimming, and cycling. It has been suggested that older adults consume a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, lean meat, and fish. It is recommended that at least five servings of fruits and vegetables be consumed daily. Each meal should contain sufficient protein sources such as beans, nuts, eggs, and fish to support muscle health. Older adults should reduce their intake of added sugars and salt, select natural ingredients, and avoid processed foods to lower the risk of chronic diseases. Health education includes topics such as choosing healthy foods, developing exercise plans, and identifying risk factors for falls. The 24-week active learning program covering exercise, diet, nutrition, and cognitive activities was implemented to enhance the health literacy and quality of life of older adults[65]. The results indicated that health education based on an active learning program improved overall health literacy, language fluency, memory, gait speed, balance, and physical strength in older adults, thereby reducing the incidence of MCR. Consequently, health education for older adults should be enhanced to promote healthier lifestyles and prevent the onset of MCR-related falls.

Exercise is a crucial means of preventing MCR-related falls in elderly individuals. Sink et al[66] conducted a multicenter randomized controlled trial involving 1635 community-dwelling elderly individuals. The experimental group participated in moderate-intensity physical exercises, including walking, resistance training, and flexibility training, whereas the control group received routine health education. These results indicate that moderate-intensity exercise significantly improves gait and cognitive function, thereby reducing the risk of MCR. Galle et al[67] conducted a randomized controlled trial involving 91 cognitively healthy elderly individuals. The experimental group engaged in a combination of aerobic and resistance exercises for 3 mo, while the control group received basic care and routine rehabilitation training. The results demonstrated that the combination of resistance and aerobic exercises was beneficial for improving neurological, motor, and cognitive functions in older adults, thereby enhancing their ability to perform activities of daily living. Additionally, activities such as Tai Chi, Baduanjin[68], and dancing[69] can prevent MCR in the elderly and are important for improving cognitive and motor functions. Therefore, various effective exercise methods should be tailored to an individual's health status to intervene and reduce the incidence of MCR-related falls.

Otaegui-Arrazola et al[70] demonstrated that good nutrition is associated with improved gait and cognitive function in older adults, as well as a reduced risk of dementia in later life. Beauchet et al[71] conducted a randomized controlled trial involving 40 community-dwelling elderly individuals. The experimental group consumed fortified yogurt containing 400 IU vitamin D3 and 800 mg calcium, whereas the control group consumed yogurt with similar levels of protein, carbohydrates, and fat but 300 mg calcium and no vitamin D3. After a 3-mo intervention, yogurt fortified with vitamin D3 significantly improved overall cognitive function and gait in older adults, thereby reducing the risk of MCR. Miller et al[72] also conducted a randomized controlled trial indicating that blueberry consumption can improve cognitive function and gait to a certain extent, potentially preventing the onset of MCR. Considering the differences in dietary habits and population characteristics across countries, large-scale trial surveys should be conducted before recommending supplementation with specific nutrients.

Computerized cognitive training

Computerized cognitive training (CCT) is a behavioral intervention designed to enhance cognitive and socioemotional functions through repetitive learning, which can positively influence underlying brain functions and help prevent MCR-related falls[73]. CCT interventions are categorized into single- and multidomain cognitive training, primarily focusing on aspects such as memory, attention, and executive function[74]. Nouchi et al[75] conducted a randomized controlled trial with 32 cognitively normal community-dwelling elderly individuals, in which the experimental group used the BrainAge computer training system and the control group used the traditional game software Tetris for cognitive training. The results indicated significant improvements in overall cognitive, executive, and motor functions in the experimental group, thereby reducing the incidence of MCR. Kwak et al[76] confirmed that resistance band training can effectively improve muscle strength and balance, thereby reducing the risk of falls. Wang et al[77] indicated that computer-based cognitive training can effectively improve the overall cognitive function of patients with MCR and enhance their daily living abilities. The amount and duration of training are key to ensuring the effectiveness of computerized cognitive interventions.

Dual-task training

Meta-analyses have demonstrated that dual-task training, which combines cognitive challenges with physical exercise, can boost the mobility of older adults and decrease their likelihood of falling[78]. Relevant studies have shown that dual-task training involves conducting 2-3 sessions/wk, with each session lasting approximately 30 min. The difficulty of tasks can start with simple tasks, such as performing basic cognitive tasks (e.g., counting) while walking, and gradually increase in complexity, such as engaging in more complex calculations or memory tasks while walking. Typically, an intervention period of 8-12 wk is used to observe effects. Evidence suggests that this training can reduce frailty, enhance cognitive and attentional skills, and prevent falls in individuals with MCR[51]. It works by fine-tuning biomechanics, enhancing movement control of the nervous system, promoting neuroplasticity, and encouraging brain remodeling, all of which contribute to an improved gait[79]. In 2023, Chen et al[80] demonstrated that dual-task training combining cognitive and physical exercises significantly improved dual-task performance in older adults. Furthermore, dual-task training sharpens the brain's ability to allocate cognitive resources, swiftly switch between tasks, and coordinate these resources across different activities, allowing for more efficient prioritization of cognitive efforts. However, the success of this training is heavily influenced by the choice and difficulty levels of the cognitive tasks involved. Tasks that cause internal interference, such as executive calculations or memory challenges, have a greater negative impact on gait and are more accurate in predicting fall risk than those that cause external interference[81]. The lack of standardized guidelines for selecting and grading cognitive tasks in dual-task training calls for the creation of customized programs for populations with MCR to maximize cognitive and physical performance and reduce the risk of falls.

CONCLUSION

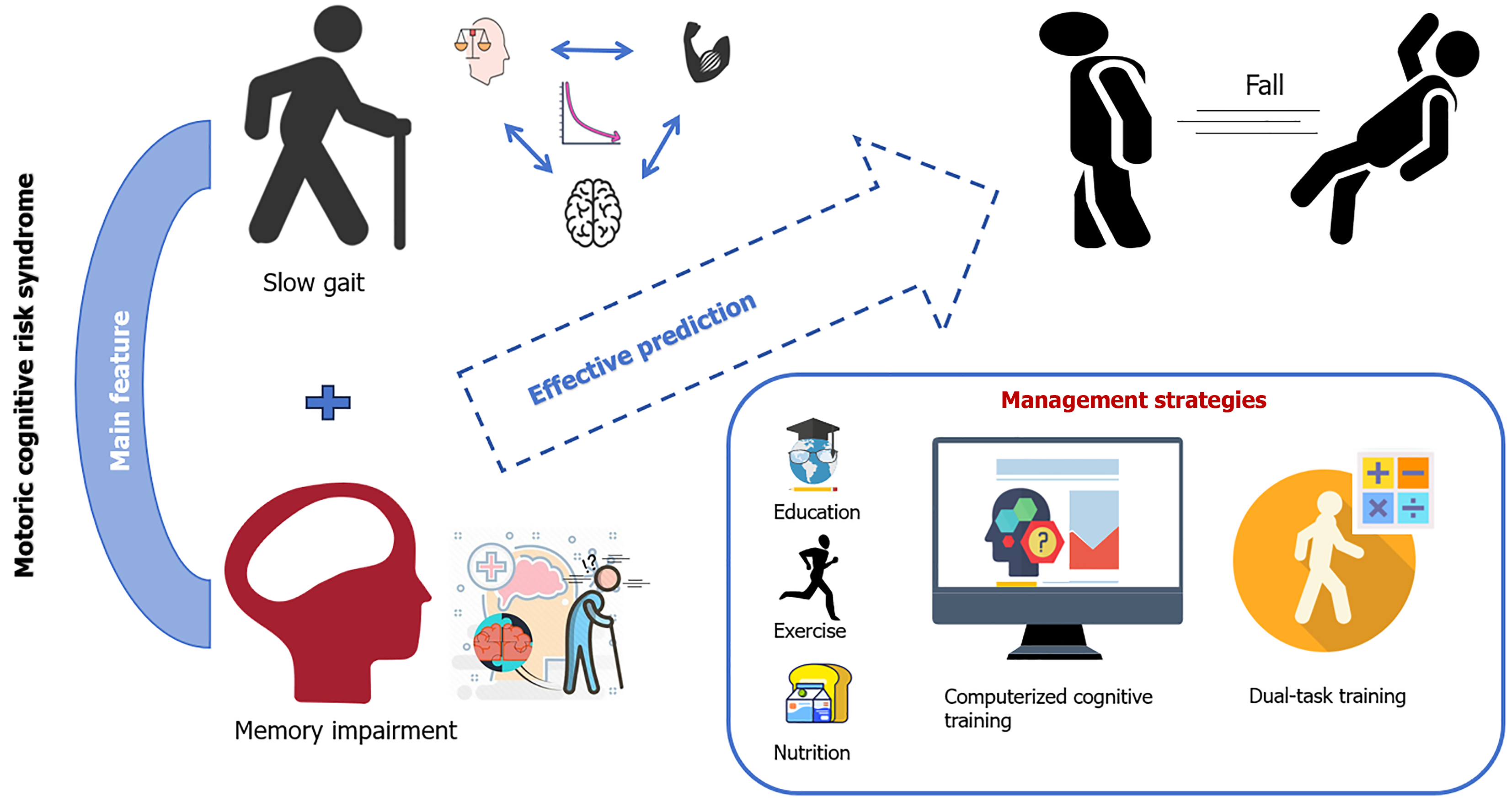

This review underscores the significance of MCR syndrome as a pre-dementia condition that is not only predictive of dementia but also significantly associated with the risk of falls in the elderly. The synthesis of the current research reveals that MCR, characterized by subjective memory impairment and SG, is a critical factor in identifying individuals at high risk of falls (Figure 4). Although the global prevalence of MCR varies, it has consistently emerged as a significant predictor of falls, disability, and mortality. This review highlights the importance of early screening and intervention for MCR to delay the onset of dementia and improve fall regulation, thereby offering a novel perspective for elderly health management. Future research should be directed toward precisely identifying, managing, and evaluating the specific fall risk factors associated with MCR syndrome. Therefore, it is essential to develop a customized fall management plan that considers the unique cognitive, physical, and psychological attributes of the elderly population. Future research should delve deeper into the prevalence of MCR and its effect on fall risk across different cultural backgrounds and geographic environments. For instance, studies could explore how dietary habits, lifestyles, and social support systems in various regions affect the occurrence and progression of MCR. Additionally, more randomized controlled trials on comprehensive intervention measures, such as combining physical and cognitive training, should be conducted to assess their effectiveness and feasibility in different cultural contexts. We also hope that in the future, governments and relevant agencies will develop targeted public health policies to raise public awareness of MCR and its associated fall risk and to provide more resources for prevention and intervention. By doing so, we can enhance the efficacy of fall prevention strategies and ensure the safety and well-being of community-dwelling older adults.

Figure 4 The mechanism of motoric cognitive risk syndrome and its relationship with falls, as well as preventive measures.