Published online Apr 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.101105

Revised: November 17, 2024

Accepted: February 7, 2025

Published online: April 19, 2025

Processing time: 202 Days and 2.6 Hours

Depression is a leading global health concern with high suicide rates and recur

To determine the mediating role of automatic thoughts in the relationship bet

This cross-sectional study included 389 inpatients with depression from Tianjin Anding Hospital. Participants completed the Self-Compassion Scale-Chinese Version (SCS-C), Automatic Thought Questionnaire (ATQ), and Orbach & Mikulincer Mental Pain Scale-Chinese Version (OMMP). Data were analyzed using Pearson correlations, multiple linear regressions, and mediation analysis.

The SCS-C total score was 68.95 ± 14.89, ATQ was 87.02 ± 28.91, and OMMP was 129.01 ± 36.74. Correlation analysis showed mental pain was positively associated with automatic thoughts (r = 0.802, P < 0.001) and negatively with self-compassion (r = -0.636, P < 0.001). Regression analysis indicated automatic thoughts (β = 0.623, P < 0.001) and self-compassion (β = -0.301, P < 0.001) significantly predicted mental pain. Mediation analysis confirmed automatic thoughts partially mediated the relationship between self-compassion and mental pain (ab = -0.269, 95%CI: -0.363 to -0.212).

Self-compassion is inversely related to mental pain in depression, with automatic thoughts playing a mediating role. These findings suggest potential therapeutic targets for alleviating mental pain in depressed patients.

Core Tip: This observational study reveals that self-compassion is negatively correlated with mental pain in individuals with depression, while automatic thoughts mediate this relationship. The findings underscore the importance of self-compassion in reducing mental pain and suggest that addressing automatic thoughts could be a key intervention for improving mental health outcomes in depression.

- Citation: Ren LN, Pang JS, Jiang QN, Zhang XF, Li LL, Wang J, Li JG, Ma YY, Jia W. Self-compassion, automatic thoughts, and mental pain in depression: Mediating effects and clinical implications. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(4): 101105

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i4/101105.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.101105

Depression is a prevalent and impactful mental health issue among college students, recognized as a significant global public health concern due to its association with high suicide rates and recurrence[1]. Since Beck proposed the cognitive model of depression, cognitive factors related to depression have become the primary explanatory variables for this issue[2]. Currently, there are approximately 350 million cases of depression worldwide, with a lifetime prevalence rate of 6.9% in China. Mental pain, as a negative emotional experience and a state of negativity, is a key factor in inducing individual suicide[3].

Research suggests that mental suffering is a pivotal factor in the suicidal tendencies of those with depression. Emphasizing mental pain's role in suicidal ideation can improve patients' ability to understand, interpret, and evaluate their suicidal thoughts, thereby strengthening their problem-solving abilities[4]. As a result, mental pain has become a pressing concern in the field of mental health. Experts believe that mental pain stems from cognitive biases, with automatic thoughts playing a central role in this cognitive process[5]. While there is no universal agreement on the definition of automatic thoughts, they are generally viewed as involuntary mental processes. For individuals with depression, these automatic thoughts tend to concentrate on negative aspects, triggering mental pain[6]. Self-compassion, a construct originating from Buddhist philosophy, was defined by Neff and Dahm[7] as an open and understanding attitude toward oneself when confronted with one’s own weaknesses, inadequacies, and suffering. This concept encompasses not only self-affirmation and acceptance found in self-esteem but also connects the self with others and the shared human experience[7]. Self-esteem, once considered a crucial trait for self-acceptance, has been challenged by research suggesting that it is more a consequence than a cause of success[8], and that high self-esteem can lead to an unrealistically positive assessment of one's abilities[9]. Given the potential negative impacts of self-esteem, studies introduced the concept of self-compassion, which includes self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness[7,10]. The characteristics of self-compassion in depressed patients include difficulty in self-warming and understanding, inability to accurately perceive human imperfections, and excessive identification with negative thoughts and emotions[11]. Surveys across diverse groups, including university students and those with obesity, reveal that higher self-compassion is associated with fewer negative emotions, which in turn predict fewer negative psychological experiences[12]. Self-compassion is closely tied to automatic thoughts and mental pain. Some studies of emotional reactions highlights the central role of automatic thoughts in emotion development, as they significantly link to individual negative emotions[13,14].

The interaction between automatic thoughts, self-compassion, and mental pain influences emotional responses to negative events through cognitive processing. Research is scarce on how these factors interrelate in depressed patients, particularly from a positive psychology viewpoint. The design of the research is grounded in Smith's emotional response theory model[14], which posits that emotional experiences are shaped by cognitive appraisals of events. In the current research landscape regarding depression, while numerous studies have explored the individual relationships between self-compassion, automatic thoughts, and mental pain, a significant research gap exists. There is a lack of comprehensive investigations that precisely define how automatic thoughts mediate the relationship between self-compassion and mental pain in depressed patients from a positive psychology perspective.

This study's originality lies in filling this void. By specifically aiming to determine the mediating role of automatic thoughts in the relationship between self-compassion and mental pain, it bridges the gap in understanding these complex psychological mechanisms. This approach not only enriches the existing knowledge about depression but also offers new insights for potential therapeutic interventions, thereby enhancing the overall understanding of mental health in the context of depression.

This study employed convenience sampling to recruit 389 depressed inpatients from Tianjin Anding Hospital between October 2020 and November 2023. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Anding Hospital (Approval No. 2024-52).

Inclusion criteria included: (1) Age between 18-65 years; (2) Diagnosis of depression according to the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; (3) A Hamilton Depression Scale-24 score of 8 or higher; and (4) The ability to communicate, express, and understand normally.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) Presence of other mental disorders; (2) Inability to self-care; or (3) Intellectual disabilities.

Before data collection commenced, researchers provided comprehensive training to all survey participants. This ensured that participants understood the nature of the questionnaires and how to respond accurately. Patient data was systematically gathered upon admission. Standardized protocols were strictly adhered to throughout the process of questionnaire completion. To maintain data integrity, for participants who faced reading difficulties, trained surveyors offered personalized assistance. Any questionnaires with consistent, potentially non-genuine responses, those with more than two - thirds of the questions missing, or those exhibiting suspicious patterns were immediately identified and invalidated, and subsequently excluded from the dataset.

Automatic thought questionnaire: The Automatic Thought Questionnaire (ATQ), by Hollon and Kendall[15], assesses the frequency of 30 thoughts over the past week on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always), with scores ranging from 30 to 150. It is primarily used for depressed patients and has a Cronbach's α of 0.98.

Self-Compassion Scale-Chinese Version: The Self-Compassion Scale-Chinese Version (SCS-C), adapted by Chen et al[16], measures self-kindness, mindfulness, and common humanity across 26 items on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = almost never, 5 = almost always). Higher scores indicate greater self-compassion, with a Cronbach's α of 0.870[16].

Orbach & Mikulincer Mental Pain Scale-Chinese Version: The Orbach & Mikulincer Mental Pain Scale-Chinese Version (OMMP), revised by our team, includes 39 items across 8 dimensions, rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), with total scores from 39 to 195. It has been used in diverse populations and has a Cronbach's α ranging from 0.78 to 0.95[17].

General Information Questionnaire: We developed a questionnaire to collect patients' demographic and clinical data, including gender, age, education, marital status, occupation, income, depression severity, self-harm/suicide history, and relapse frequency.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 25.0, with continuous data represented as mean ± SD and categorical data as frequency and percentage. Pearson correlation tests and multiple linear regression analyses were used for correlation and multivariate analysis, respectively. Independent sample t-tests and ANOVA analyses were applied to data conforming to normal distribution and homogeneity of variance. The Bootstrap method in SPSS was employed to test the mediating role of automatic thoughts between self-compassion and psychological pain, with P < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

The study sample comprised 389 depressed patients, with the majority aged between 18-30 years (54.2%) and females (65.3%). The majority of participants had a college or higher education level (70.8%). Regarding marital status, 51.7% were single and 48.3% were married. The most common occupations were unit employee (22.1%) and student (36.8%). The majority of participants had a family monthly income between 5000-7999 China yuan (56.8%). In terms of depression severity, 17.2% had mild, 66.1% had moderate, and 16.7% had severe depression. A history of suicide or self-harm was reported by 46.5% of the patients. Regarding recurrence, 46.1% were experiencing their first episode, 22.1% had one prior episode, 16.7% had two, 5.7% had three, and 9.5% had four or more episodes (Table 1).

| Items | Category | Case count (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Age (years) | 18-30 | 210 | 54.2 |

| 31-40 | 81 | 20.8 | |

| 41-50 | 53 | 13.6 | |

| 51-65 | 45 | 11.6 | |

| Gender | Male | 135 | 34.7 |

| Female | 254 | 65.3 | |

| Education | Junior high or below | 58 | 14.9 |

| High school or vocational | 48 | 12.3 | |

| College or above | 275 | 70.8 | |

| Marital status | Single | 201 | 51.7 |

| Married | 188 | 48.3 | |

| Occupation | Farmer | 6 | 1.5 |

| Enterprise employee | 73 | 18.8 | |

| Public servant | 43 | 11.0 | |

| Unit employee | 86 | 22.1 | |

| Self-employed | 41 | 10.5 | |

| Student | 141 | 36.8 | |

| Family monthly income (CNY) | ≤ 3000 | 16 | 4.1 |

| 3000-4999 | 44 | 11.3 | |

| 5000-7999 | 221 | 56.8 | |

| More than 8000 | 10 | 2.6 | |

| Depression severity | Mild | 67 | 17.2 |

| Moderate | 257 | 66.1 | |

| Severe | 65 | 16.7 | |

| History of suicide or self-harm | None | 208 | 53.5 |

| Yes | 181 | 46.5 | |

| Recurrence times | First episode | 179 | 46.1 |

| 1 time | 86 | 22.1 | |

| 2 times | 65 | 16.7 | |

| 3 times | 22 | 5.7 | |

| 4 times or more | 37 | 9.5 |

The SCS-C indicates an overall mean score of 68.95 (Table 2), with standard deviations suggesting variability in self-kindness (27.43), common humanity (21.58), and mindfulness (20.37). The ATQ shows a higher mean score of 87.02, reflecting the frequency of automatic thoughts among participants. The OMMP presents the highest mean score at 129.01, with subscales delineating distinct aspects of mental pain, including irreversibility (30.45), loss of control (30.73), narcissistic wound (13.98), emotional collapse (14.76), emotional numbing (10.65), self-alienation (9.67), confusion (10.23), and a sense of emptiness (10.04).

| Scale component | mean ± SD |

| SCS-C | |

| Total SCS-C | 68.95 ± 14.89 |

| Self-kindness | 27.43 ± 7.87 |

| Common humanity | 21.58 ± 5.71 |

| Mindfulness | 20.37 ± 5.82 |

| ATQ | |

| Total ATQ | 87.02 ± 28.91 |

| OMMP | |

| Total OMMP | 129.01 ± 36.74 |

| Irreversibility | 30.45 ± 9.08 |

| Loss of control | 30.73 ± 9.41 |

| Narcissistic wound | 13.98 ± 5.67 |

| Emotional collapse | 14.76 ± 4.39 |

| Emotional numbing | 10.65 ± 3.51 |

| Self-alienation | 9.67 ± 3.74 |

| Confusion | 10.23 ± 2.98 |

| Sense of emptiness | 10.04 ± 3.95 |

The Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant relationships among mental pain, automatic thoughts, and self-compassion in the study cohort. As shown in Table 3, mental pain was positively correlated with automatic thoughts (r = 0.802, P < 0.001), indicating that an increase in the frequency of automatic thoughts is associated with higher levels of mental pain. Conversely, mental pain was negatively correlated with self-compassion (r = -0.645, P < 0.001), suggesting that higher self-compassion is linked to lower levels of mental pain. Additionally, automatic thoughts were negatively correlated with self-compassion (r = -0.612, P < 0.001), which implies that as self-compassion increases, the frequency of automatic thoughts decreases.

| Correlation | Mental pain | Automatic thoughts | Self-compassion |

| Mental pain | / | r = 0.802, P < 0.001 | r = -0.645, P < 0.001 |

| Automatic thoughts | / | / | r = -0.612, P < 0.001 |

| Self-compassion | / | / | / |

Using the OMMP score of depressed patients as the dependent variable and the statistically significant ATQ total score and SCS-C total score from the correlation analysis as independent variables, multiple linear regression analysis was conducted. The multiple linear regression analysis, presented in Table 4, identified automatic thoughts and self-compassion as significant predictors of mental pain. The model indicated that automatic thoughts positively predict mental pain (β = 0.623, P < 0.001), while self-compassion negatively predicts mental pain (β = -0.301, P < 0.001).

| Independent variable | Unstandardized coefficients | Standard error | Standardized coefficients (beta) | t | P value |

| Constant | 85.847 | 10.523 | |||

| Automatic thoughts | 0.796 | 0.031 | 0.623 | 10.396 | < 0.001 |

| Self-compassion | -0.369 | 0.063 | -0.301 | -2.392 | < 0.001 |

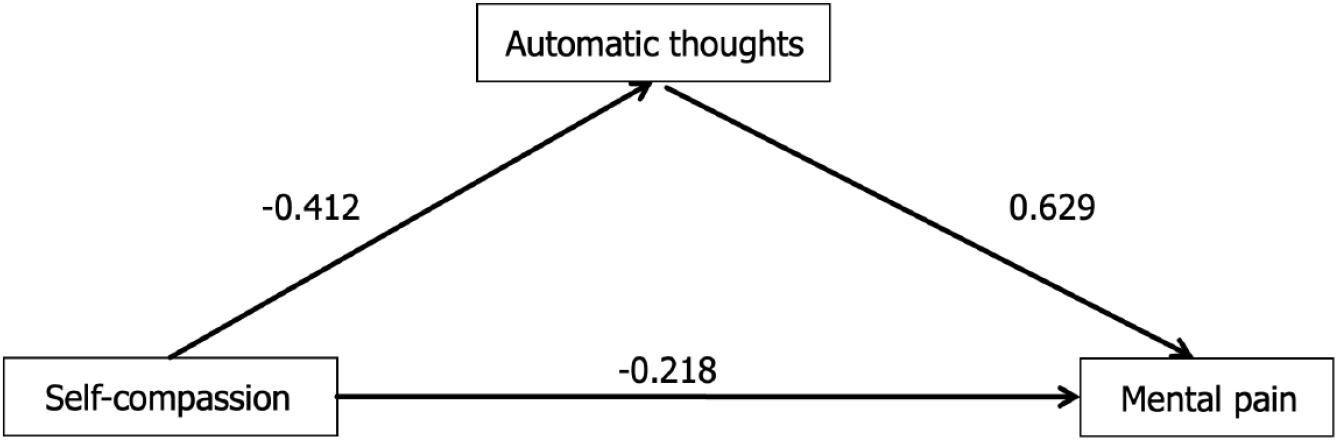

The potential for common method bias was evaluated using a Harman single-factor test. The analysis revealed 14 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, with the first factor explaining 30.69% of the total variance, which is below the critical threshold of 40%. Adopting the methodology proposed by Ying[18] , we utilized Model 3 in the SPSS macro PROCESS to investigate the mediating role of automatic thoughts between self-compassion and mental pain. The analysis demonstrated that self-compassion significantly predicted automatic thoughts (unstandardized coefficient = -0.412, standard error = 0.051, P < 0.001) and mental pain (unstandardized coefficient = -0.218, standard error = 0.032, P < 0.001). Automatic thoughts were also found to significantly predict mental pain (unstandardized coefficient = 0.629, standard error = 0.052, P < 0.001). The mediating effect of automatic thoughts was further confirmed by the bias-corrected percentile Bootstrap method, which indicated a significant indirect effect (ab = -0.269, Boot SE = 0.042, 95%CI: -0.363 to -0.212). The proportion of the indirect effect to the total effect was calculated to be 58.6%, suggesting that automatic thoughts partially mediate the relationship between self-compassion and mental pain. The relationship among the three variables is shown in Figure 1 and Table 5.

| Effect | Path | Unstandardized coefficient | SE | t | P value | 95%CI |

| Direct effect | Self-compassion to mental pain | -0.218 | 0.032 | -4.531 | < 0.001 | -0.282 to -0.154 |

| Indirect effect | Self-compassion to automatic thoughts | -0.412 | 0.051 | -8.073 | < 0.001 | -0.515 to -0.309 |

| Automatic thoughts to mental pain | 0.629 | 0.052 | 12.089 | < 0.001 | 0.527-0.732 | |

| Total effect | Self-compassion to mental pain | -0.473 | 0.050 | -9.461 | < 0.001 | -0.572 to -0.375 |

This study verified for the first time the correlation between mental pain and self-compassion in the depression population. The results indicate a negative effect between mental pain and self-compassion, suggesting that the higher the degree of self-compassion in depression patients, the lower the level of mental pain. This further confirms that self-compassion acts as a psychological buffering factor in promoting the mental health of patients with depression. Mills et al[19] found that even when controlling for variables such as self-criticism and self-esteem, self-compassion is negatively correlated with anxiety and depression, as individuals' rigid beliefs are often associated with habits of self-criticism and self-attack. Ying[18] in studying the relationship between the subcomponents of self-compassion and depression, discovered that self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification are positively correlated with depression, while self-kindness and mindfulness are negatively correlated with depression. This proves that effectively increasing the positive components of an individual's psychology and reducing the negative components can alleviate the symptoms of depression.

The mechanism by which self-compassion reduces the mental pain of depression patients is mainly related to mindfulness, universal humaneness, and self-kindness[10]. Self-kindness is characterized by the application of warmth, tolerance, and understanding towards oneself; universal humaneness acknowledges the collective nature of suffering as a shared human experience; mindfulness entails a non-judgmental and objective awareness of one's own distressing thoughts[20]. Mindfulness stands as the central pillar of self-compassion, classified among advanced regulatory mechanisms, exerting a direct influence on self-kindness and universal humaneness, which are essential for maintaining an individual's mental health within an optimal range[21]. Reciprocally, self-kindness and universal humaneness also amplify mindfulness, creating a synergistic effect between these elements. Consequently, psychotherapeutic approaches that prioritize mindfulness are deemed crucial for mitigating mental pain and fostering self-compassion in individuals diagnosed with depression.

The correlation analysis revealed a significant positive link between mental pain and automatic thoughts, suggesting that increased frequency of automatic thoughts in depressed patients is associated with intensified distress. Research by Wang et al[22] supports this, showing a negative correlation between negative automatic thoughts and psychological functioning in depression, aligning with our study's findings. Automatic thoughts, originating from cognitive distortions, often emerge in response to specific triggers, evoking distressing cognitions. Deficits in cognition are a significant contributor to mental pain, as evidenced by a positive correlation between the two in the context of depression[23]. Targeting cognition in therapeutic interventions is thus a potent strategy for reducing mental pain in these patients. Zou et al[24] demonstrated the efficacy of an 8-week cognitive therapy program based on psychological pain theory in reducing mental pain for patients with severe depression. Additionally, nursing staff can employ psychological diary techniques to track mood fluctuations, identify negative automatic thoughts promptly, and assist patients in challenging and reframing these thoughts, promoting more positive cognitive patterns. The mediation model indicates that automatic thoughts play a partial mediating role in the relationship between self-compassion and mental pain. Self-compassion is shown to have both direct and indirect effects on mental pain, with the latter being mediated by automatic thoughts[25]. While high levels of automatic thoughts are associated with increased self-blame and diminished self-compassion, the components of self-kindness and universal humaneness within self-compassion can mitigate self-critical tendencies in depression, fostering emotional connection and reducing mental pain. However, automatic thoughts are susceptible to influence from stressors. Stressful events, when they act as triggers, can activate entrenched core beliefs, leading to negative interpretations of life events and subsequent emotional suffering[26]. Consequently, stressors may attenuate the mediating influence of automatic thoughts between self-compassion and mental pain. It is imperative for nursing staff to be attentive to patients' stressors and life histories to pinpoint the sources of their distress and deliver tailored nursing interventions.

The current study, while providing valuable insights into the relationship between mental pain, self-compassion, and automatic thoughts in depressed patients, is not without limitations. We could expand on these limitations with more actionable suggestions for future research. Given the cross - sectional design that restricts establishing causality, future research should adopt longitudinal designs to determine the direction of effects and temporal stability of relationships among the variables. Also, as the sample was from a specific clinical setting, future studies should aim for a more diverse and representative sample to enhance generalizability. Considering the study's sole reliance on self - report measures, which are prone to social desirability and recall biases, incorporating objective measures or observational data would strengthen the validity of findings. Moreover, although some variables were controlled, there may be unaccounted confounding factors affecting the relationships. Despite these limitations, the study offers a meaningful contribution to the understanding of psychological mechanisms in depression and can inform future research and clinical practices.

In conclusion, the present study has delineated the complex interplay between mental pain, self-compassion, and automatic thoughts among individuals with depression. The findings highlight the significance of self-compassion as a protective factor that mitigates mental pain, with automatic thoughts serving as a partial mediator in this dynamic. By targeting these psychological constructs through therapeutic interventions, there is a potential to reduce the psychological suffering and suicide rates among patients with depression. The study's conclusions stress the importance of developing and implementing psychological treatment strategies aimed at enhancing self-compassion and managing automatic thoughts, thereby contributing to improved mental health outcomes and a decreased incidence of suicidality in this vulnerable population.

We would like to express our gratitude to the staff at Tianjin Anding Hospital and all the participants who made this study possible. Our appreciation also goes to the research assistants for their efforts in data collection and management.

| 1. | Sousa RD, Gouveia M, Nunes da Silva C, Rodrigues AM, Cardoso G, Antunes AF, Canhao H, de Almeida JMC. Treatment-resistant depression and major depression with suicide risk-The cost of illness and burden of disease. Front Public Health. 2022;10:898491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Beck AT, Haigh EA. Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: the generic cognitive model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:1-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 41.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gutoreva A, Olin SL. Cognitive causes of the mental state of terror and their link to mental health outcomes. J Health Psychol. 2024;29:1704-1718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | David Rudd M, Bryan CJ, Jobes DA, Feuerstein S, Conley D. A Standard Protocol for the Clinical Management of Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior: Implications for the Suicide Prevention Narrative. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:929305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Buschmann T, Horn RA, Blankenship VR, Garcia YE, Bohan KB. The Relationship Between Automatic Thoughts and Irrational Beliefs Predicting Anxiety and Depression. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther. 2018;36:137-162. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Beck AT. The evolution of the cognitive model of depression and its neurobiological correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:969-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 864] [Cited by in RCA: 900] [Article Influence: 52.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Neff KD, Dahm KA. Self-Compassion: What It Is, What It Does, and How It Relates to Mindfulness. In: Ostafin B, Robinson M, Meier B, editors. Handbook of Mindfulness and Self-Regulation. New York (NY): Springer, 2015. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Călin MF, Tasențe T. Self-acceptance in today's young people. Tech Soc Sci J. 2022;38:367-379. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Neff KD. Self‐Compassion, Self‐Esteem, and Well‐Being. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2011;5:1-12. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Neff KD. Self-Compassion: Theory, Method, Research, and Intervention. Annu Rev Psychol. 2023;74:193-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 101.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Human LJ, Biesanz JC. Targeting the good target: an integrative review of the characteristics and consequences of being accurately perceived. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2013;17:248-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | López A, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV, Schroevers MJ. Compassion for Others and Self-Compassion: Levels, Correlates, and Relationship with Psychological Well-being. Mindfulness (N Y). 2018;9:325-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pedro L, Branquinho M, Canavarro MC, Fonseca A. Self-criticism, negative automatic thoughts and postpartum depressive symptoms: the buffering effect of self-compassion. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2019;37:539-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Smith CA. Dimensions of appraisal and physiological response in emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:339-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hollon SD, Kendall PC. Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cogn Ther Res. 1980;4:383-395. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 884] [Cited by in RCA: 754] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen J, Yan LS, Zhou LH. [Reliability and validity of Chinese version of Self-compassion Scale]. Zhongguo Linchuang Xinlixue Zazhi. 2011;19:734-736. |

| 17. | Cheng Y, Chen SY, Zhao WW, Zhang G, Wang TT, Wang ZQ, Zhang YH. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and psychometric investigation of Chinese version of the Orbach & Mikulincer Mental Pain Scale in patients with depressive disorder. Qual Life Res. 2023;32:905-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ying Y. Contribution of Self-Compassion To Competence And Mental Health In Social Work Students. J Soc Work Educ. 2009;45:309-323. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Mills A, Gilbert P, Bellew R, Mcewan K, Gale C. Paranoid beliefs and self‐criticism in students. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2007;14:358-364. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Brinckman B, Alfaro E, Wooten W, Herringa R. The promise of compassion-based therapy as a novel intervention for adolescent PTSD. J Affect Disord Rep. 2024;15:100694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Britton WB, Desbordes G, Acabchuk R, Peters S, Lindahl JR, Canby NK, Vago DR, Dumais T, Lipsky J, Kimmel H, Sager L, Rahrig H, Cheaito A, Acero P, Scharf J, Lazar SW, Schuman-Olivier Z, Ferrer R, Moitra E. From Self-Esteem to Selflessness: An Evidence (Gap) Map of Self-Related Processes as Mechanisms of Mindfulness-Based Interventions. Front Psychol. 2021;12:730972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang H, Xu J, Yu M, Ma X, Li Y, Pan C, Ren J, Liu W. Altered Functional Connectivity of Ventral Striatum Subregions in De-novo Parkinson's Disease with Depression. Neuroscience. 2022;491:13-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Seeher KM, Low LF, Reppermund S, Slavin MJ, Draper BM, Kang K, Kochan NA, Trollor JN, Sachdev PS, Brodaty H. Correlates of psychological distress in study partners of older people with and without mild cognitive impairment (MCI) - the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18:694-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zou Y, Li H, Shi C, Lin Y, Zhou H, Zhang J. Efficacy of psychological pain theory-based cognitive therapy in suicidal patients with major depressive disorder: A pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;249:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Calvete E, Orue I, Hankin BL. Early maladaptive schemas and social anxiety in adolescents: the mediating role of anxious automatic thoughts. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27:278-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lee DA, Scragg P, Turner S. The role of shame and guilt in traumatic events: a clinical model of shame-based and guilt-based PTSD. Br J Med Psychol. 2001;74:451-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |