Published online Apr 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.100289

Revised: December 23, 2024

Accepted: January 23, 2025

Published online: April 19, 2025

Processing time: 224 Days and 20.2 Hours

Major depressive disorder (MDD) with comorbid anxiety is an intricate psychiatric condition, but limited research is available on the degree centrality (DC) between anxious MDD and nonanxious MDD patients.

To examine changes in DC values and their use as neuroimaging biomarkers in anxious and non-anxious MDD patients.

We examined 23 anxious MDD patients, 30 nonanxious MDD patients, and 28 healthy controls (HCs) using the DC for data analysis.

Compared with HCs, the anxious MDD group reported markedly reduced DC values in the right fusiform gyrus (FFG) and inferior occipital gyrus, whereas elevated DC values in the left middle frontal gyrus and left inferior parietal angular gyrus. The nonanxious MDD group exhibited surged DC values in the bilateral cerebellum IX, right precuneus, and opercular part of the inferior frontal gyrus. Unlike the nonanxious MDD group, the anxious MDD group exhibited declined DC values in the right FFG and bilateral calcarine (CAL). Besides, declined DC values in the right FFG and bilateral CAL negatively correlated with anxiety scores in the MDD group.

This study shows that abnormal DC patterns in MDD, especially in the left CAL, can distinguish MDD from its anxiety subtype, indicating a potential neuroimaging biomarker.

Core Tip: In this study, we investigated brain regions with altered degree centrality (DC) values by detecting DC in anxious major depressive disorder (MDD) patients and non-anxious MDD patients, and characterized them as possible neuroimaging biomarkers using receiver operating characteristic analysis. The results of our study showed that DC values of the right fusiform gyrus and bilateral calcarine (CAL) were reduced in the anxious MDD group compared to the non-anxious MDD group. Abnormal DC values in the left CAL may distinguish MDD from its anxiety subtype and serve as a potential neuroimaging biomarker for anxious MDD.

- Citation: Gao YJ, Meng LL, Lu ZY, Li XY, Luo RQ, Lin H, Pan ZM, Xu BH, Huang QK, Xiao ZG, Li TT, Yin E, Wei N, Liu C, Lin H. Degree centrality values in the left calcarine as a potential imaging biomarker for anxious major depressive disorder. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(4): 100289

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i4/100289.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i4.100289

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a characteristic mental ailment manifested by symptoms like lessened interest or pleasure in regular activities, persistent low mood, and anhedonia[1,2]. Notably, MDD is an important precursor to suicide[3]. The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic led to a surge of multiple health-related issues, including physical and mental well-being, such as conditions like sadness, anxiety, and altered sleep patterns[4]. Comorbid anxiety occurs in 2 of 5 MDD patients and correlates with considerable differences in several factors[5]. Anxious MDD, also defined in the latest versions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), is a subtype of MDD with comorbid anxiety disorder, distinguished by supplementary complicated and severe symptoms, impaired adaptive function, and abject prognosis[1,5]. Patients fulfilling the syndrome criteria for anxious MDD reported anxiety symptoms besides an MDD diagnosis (based on the DSM criteria). Compared with nonanxious MDD patients, those with comorbid anxiety and MDD exhibited more complex and severe symptoms, including an increased frequency of major depressive episodes, along with higher rates of serious suicidal thoughts and attempts at suicide[6,7]. Besides, there exists addi

With the evolution of neuroimaging technology, noninvasive and objective results have rendered neuroimaging a vital tool to assess the etiology and pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric disorders[12-14]. Previous studies have suggested a correlation between childhood experiences in MDD patients and the presence of functional and structural anomalies in certain brain regions, including the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and medial prefrontal cortex[15]. Meanwhile, the research on structural and functional brain imaging in anxious MDD has reported several neuroimaging characteristics. For example, some studies reported prominent variations in the right dorsal anterior insula’s cortical-limbic network and the right ACC in patients with comorbid anxiety and MDD during resting-state assessments of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF), suggesting a potential correlation between the physiological and pathological features of anxious MDD[16]. Li et al[17] observed notably lower fractional ALFF (fALFF) values in the ACC and insula of patients with anxious MDD compared with those without anxiety and healthy control (HC) participants. Of note, this observation was obtained during the measurement of fALFF and regional homogeneity (ReHo) in male and female MDD patients, both with and without anxiety. Furthermore, Peng et al[11] reported a higher gray matter (GM) volume in the left posterior central gyrus in anxious MDD than in nonanxious MDD and a higher GM volume in the left cuneus than in HCs, revealing that the occurrence of structural anomalies in brain regions is related to emotional regulation and sensory processing in anxious MDD patients.

The graph theory-based method offers remarkable potential in the examination of brain networks and the quantitative assessment of their connection features[18]. Graph theory is an essential tool in the field of image data processing, especially in the analysis of brain networks that comprise interconnected nodes and edges, offering crucial methods for assessing their properties and characteristics[19]. The assessment of global connectivity in the degree centrality (DC) encompasses using the graph theory, whereby the quantification of instant functional connections between a node/region and the remainder of the brain is completed. This approach enables identifying the significance and position of a specified brain region within the network, facilitating reproducible brain mapping[20-23]. Besides, the DC could lessen bias occurring because of the identification of brain areas based on preconceived ideas while enhancing sensitivity and specificity[24]. Thus, the DC has been expansively used as a research tool for exploring neurological and mental issues, and identifying variations in the functional connectivity (FC) within brain networks. Prior research has demonstrated that the DC is markedly affected in patients with depression or anxiety disorders. Specifically, compared with HCs, anxious patients displayed surged DC values in the left middle temporal gyrus of the cerebellum bilaterally and declined DC values in the left medial frontal orbital gyrus, fusiform gyrus (FFG), and posterior cingulate cortex bilaterally[25]. A study differentiating between HCs, subclinical depression, and MDD using DC values reported variations in DCs in the superior temporal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, and frontal gyrus of the depression group[26]. Chen et al[27] reported that DC values were lower in the left insula of patients with mild to moderate depression compared with HCs. These findings suggested the utility of the DC in identifying underlying mechanisms of depression. A recent study investigating purely anxious individuals and those with comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms observed a common pattern of disconnection in limbic-cerebellar brain structures using a DC-value approach[28]. Besides, DC methods have been used to examine several disorders like epilepsy[29], schizophrenia[30,31], bipolar disorder[32], and Parkinson’s disease (PD)[21].

Although ALFF and ReHo depict localized brain activity, they do not signify FC between two brain regions or between specific brain regions and the brain overall[33]. Thus, the FC analysis approach cannot identify abnormal brain regions when there is atypical FC between two brain regions or between specific brain regions and the whole brain. Conversely, the concept of DC considers the connectivity of a specific area with respect to the whole set of functional connections, rather than focusing just on its connectivity to a specific region or significant isolated components[34]. Moreover, few studies have compared DC differences between anxious and nonanxious MDD patients. Thus, our study utilized the DC techniques to identify the resting-state FC in MDD subtypes.

Overall, this study aimed to identify DC values in anxious and nonanxious MDD patients, explore brain regions with variations in DC values, and characterize them as potential neuroimaging biomarkers using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Accordingly, this study hypothesized anomalous DC values of anxious MDD patients compared with those of nonanxious MDD patients and HCs, and that ROC analyses could identify the most effective brain regions for diagnosing and identifying anxious MDD.

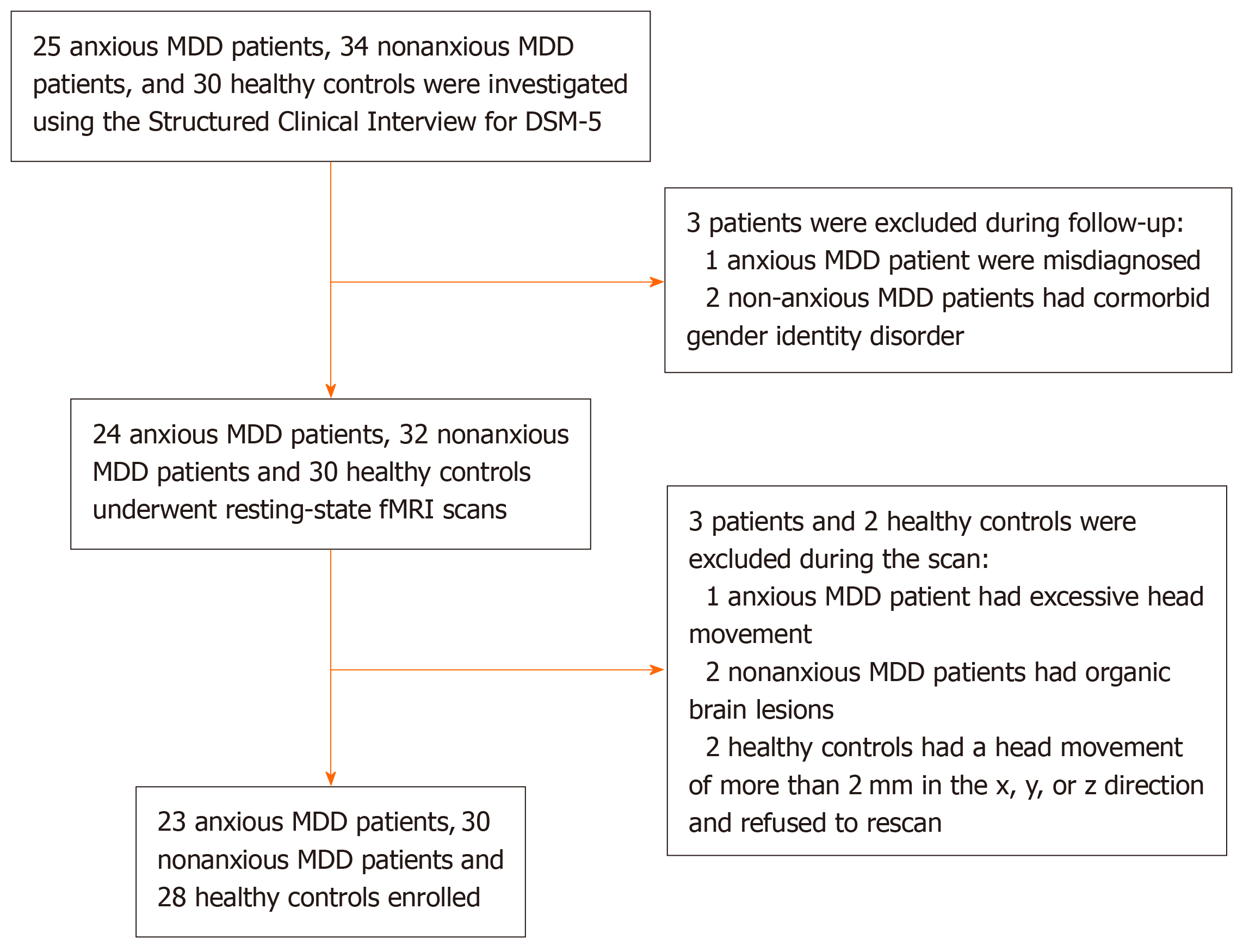

A total of 23 anxious MDD patients and 30 nonanxious MDD patients (age: 18-60 years) were enrolled from the psychiatric outpatient clinic and ward of the Department of Psychiatry, Wuhan Mental Health Center. The study duration was between April 2018 and February 2023 and the diagnoses were done independently by two psychiatrists per the DSM-5. Figure 1 presents a flowchart for the selection of anxious and nonanxious MDD patients, all of whom satisfied the following inclusion criteria: (1) Age range: 18 to 60 years; and (2) Hamilton depression scale (HAMD) score > 24. Hamilton anxiety rating scale (HAMA) score was applied to differentiate the diagnosis of MDD with and without anxiety. When HAMA score was higher than 14, anxious MDD was diagnosed. When HAMA score was lower than 14, non-anxious MDD was diagnosed. We recruited 28 HCs from the community matched by age, sex, and education. The inclusion criteria for our HC group were: (1) Right-handed; (2) Age range: 18 to 60 years; (3) No history of mental illness or substance abuse/dependence; (4) No mental or neurological disorders among first-degree relatives; (5) No psychotropic drugs or prescription drugs; (6) No alcohol has been consumed in the past week; and (7) The absence of serious medical or neurological conditions including: (i) Pregnancy or breastfeeding; and (ii) Metal implants or other magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contraindications. The research protocol received approval from the ethical committee of Department of Psychiatry, Wuhan Mental Health Center (KY2023121302), and all participants in the study supplied signed informed permission.

All brain imaging data were obtained on a Philips Achieva 3.0T MR System. All participants were provided with earplugs to decrease scanner noise and a special nonmagnetic foam pad was used to stabilize the head and lessen the head movement. The imaging instructions involved maintaining wakefulness, shutting eyes, being relaxed, refraining from any cognitive activity, and minimizing bodily movements while undergoing the scanning procedure. High-resolution 3D structural MRI was performed using a fast-spoiled gradient recalled acquisition sequence. The parameters were as follows: Echo time (TE) = 2.4 ms, repetition time (TR) = 7.38 ms, field of view (FOV) = 250 mm × 250 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, slice thickness = 1.2 mm, slice number = 230, slice interval = 0 mm, flip angle = 90°, and scan duration = 6 minutes 53 seconds. The RS blood-oxygen-level-dependent functional MRI (fMRI) data were obtained using the following parameters: TR/TE = 2200 ms/35 ms, flip angle = 90°, FOV = 230 mm × 230 mm, matrix = 128 × 128, slice number = 50, slice thickness = 3 mm, slice interval = 0 mm, and scan duration = 17 minutes 40 seconds.

The resting-state fMRI data were collected using the Statistical Parameter Mapping (SPM12) and the Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State fMRI (DPARSF5.0 Advanced Edition) toolbox in MATLAB2013b (MathWorks). To sustain magnetization balance, the data for the first five time points of each object were rejected until participants became comfortable with instrument noise. Next, the scan layer portion of all remaining time points was corrected to the middle layer. The head movement correction was done to align the data at all time points for each object with the data at the first time point. The maximum displacement of each participant’s data in the x-, y-, and z-axes did not exceed 2 mm and the maximum rotation did not exceed 2°. Corrected image data were registered in the same Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space, and all pictures of participants were normalized to the SPM standard MNI standard space with a 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm sampling resolution. Then, we performed time-domain bandpass filtering (0.01-0.08 Hz) on the generated imaging data to acquire linear detrending for reducing the high-pitched breathing and heart noise and minimizing the effect of high-frequency noise and low-frequency drift. Thereafter, head movement parameters, whole brain and white matter signals, and cerebrospinal fluid signals were returned. Finally, we performed spatial smoothing and applied a Gaussian kernel of 6 mm × 6 mm × 6 mm to perform spatial smoothing.

DC measurements for each voxel in the GM were measured using the DPARSF software. Next, we analyzed the preprocessed data, as well as extracted and examined the time progression of each voxel within the GM mask for correlations with other voxels within the same mask. Then, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the bold temporal processes of each voxel pair was finalized using MATLAB (MathWorks), and we selected a threshold of 0.25 (correlation coefficient > 0.25) to minimize the risk of including voxels whose correlation with the index voxels is attributable to noise in the centrality estimate of the index voxels. To create Z-score maps for group comparison, we transformed the DC values of every voxel in the whole brain network using Fisher’s r-to-z transformation. Before statistical analysis, the generated DC map was spatially smoothened using a Gaussian kernel (full-width half-maximum = 6 mm).

Using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) method via SPSS27.0, we examined the variations in age and years of schooling among the three study groups. A two-sample t-test was used to detect potential differences in illness duration, HAMD score, and HAMA score between the anxious and nonanxious MDD groups. In addition, the χ2 test was used to characterize the gender distribution. The significance level observed in the study was set at P < 0.05. Besides, we performed the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) on the voxel-wise whole brain DC maps to assess the variations among the three groups. Next, the post-hoc t-test was conducted between the anxious and nonanxious MDD groups, with age, years of education, and framewise displacement serving as covariates. To control the increase in Type I errors owing to multiple comparisons, we used the Bonferroni correction. Furthermore, the Gaussian random field theory was used to modify multiple comparisons using the Resting-State fMRI Data Analysis Toolkit (REST V1.8) at P < 0.01 (cluster significance: P < 0.01, voxel significance: P < 0.01)[35].

Using Pearson’s correlation analysis, we analyzed the correlation between anomalous brain region DC values and HAMA scores in the anxious MDD group. Notably, Bonferroni correction was also used for multiple comparisons.

The ROC analysis is often utilized to highlight and differentiate between the sensitivity and specificity of biomarkers in the subject population. Thus, to compare the efficacy of DC values in distinguishing the three study groups, we performed the ROC analysis to measure the sensitivity and specificity of DC values in 10 different brain regions: The right FFG, bilateral calcarine (CAL), right inferior occipital gyrus (IOG), left middle frontal gyrus (MFG), left inferior parietal angular gyrus (IPAG), bilateral cerebellum IX, right precuneus (PCu), and right opercular part of the IFG.

No statistically significant differences were observed in age, gender, and years of education among the anxious MDD, nonanxious MDD, and HC groups (P > 0.05). Meanwhile, the disease duration and HAMD scores of the anxious and nonanxious MDD groups revealed no statistical differences (P > 0.05), though we observed significant differences in HAMA scores. Furthermore, the HAMA score of the anxious MDD group was significantly higher than that of the nonanxious MDD group (P < 0.001). Table 1 presents more detailed demographic and clinical data.

| Demographic data | Anxious MDD group (n = 23) | Non-anxious MDD group (n = 30) | HC group (n = 28) | F, t, or χ2 | P value |

| Age (years) | 35.57 ± 11.30 | 30.07 ± 9.91 | 31.39 ± 8.63 | 2.105 | 0.1291 |

| Education level (years) | 12.91 ± 3.32 | 14.10 ± 3.87 | 13.46 ± 5.01 | 0.535 | 0.5881 |

| Gender (male/female) | 23 (5/18) | 30 (10/20) | 28 (11/17) | 1.817 | 0.4032 |

| Illness duration (months) | 7.64 ± 8.47 | 5.14 ± 4.22 | - | 1.402 | 0.1673 |

| HAMD score | 27.48 ± 1.62 | 27.60 ± 1.52 | - | -0.281 | 0.6273 |

| HAMA score | 20.96 ± 4.04 | 5.23 ± 1.28 | - | 17.990 | < 0.0013 |

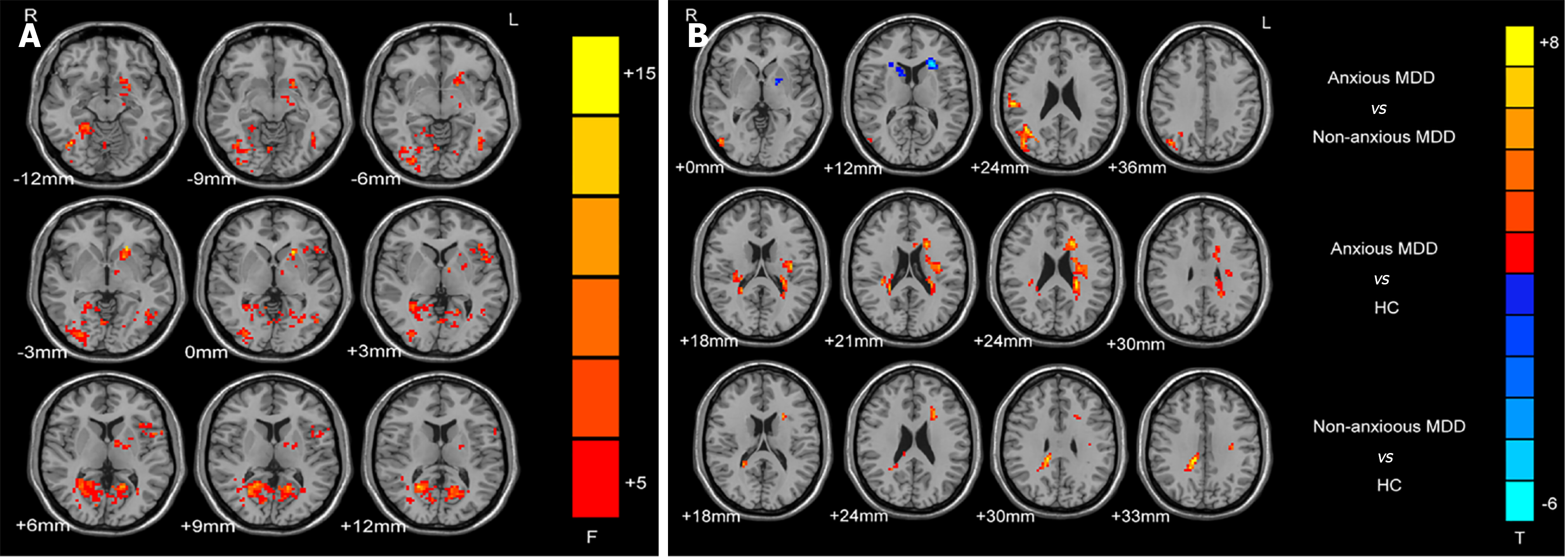

The ANCOVA determined brain regions with changed DC values among the three groups (Figure 2A). The between-group differences were primarily observed in the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, parietal lobe, and part of the cerebellum. Compared with the nonanxious MDD group, the anxious MDD group had markedly lower DC values in the right FFG and bilateral CAL (Table 2; Figure 2B). Compared with HCs, anxious MDD patients revealed markedly lower DC values in the right IOG and FFG, but considerably surged DC values in the left MFG and IPAG (Table 2; Figure 2B). Compared with HCs, nonanxious MDD patients had elevated DC values in the bilateral cerebellum IX, right PCu, and right IFOG (Table 2; Figure 2B).

| Cluster location | Peak (MNI) | Number of voxels | T value | ||

| x | y | z | |||

| Anxious MDD group vs non-anxious MDD group | |||||

| Right FFG | 21 | -45 | -15 | 48 | -5.486 |

| Left CAL | -18 | -57 | 6 | 88 | -5.671 |

| Right CAL | 15 | -69 | 18 | 151 | -5.182 |

| Anxious MDD group vs HC group | |||||

| Right IOG | 39 | -63 | -12 | 43 | -5.196 |

| Right FFG | 27 | -87 | -3 | 42 | -4.278 |

| Left MFG | -39 | 21 | 36 | 50 | 4.211 |

| Left IPAG | -54 | -51 | 42 | 36 | 4.694 |

| Non-anxious MDD group vs HC group | |||||

| Bilateral cerebellum IX | ± 6 | -42 | -30 | 93 | 5.125 |

| Right PCu | 27 | -63 | 18 | 547 | 6.320 |

| Right IFOG | 30 | 9 | 30 | 36 | 5.232 |

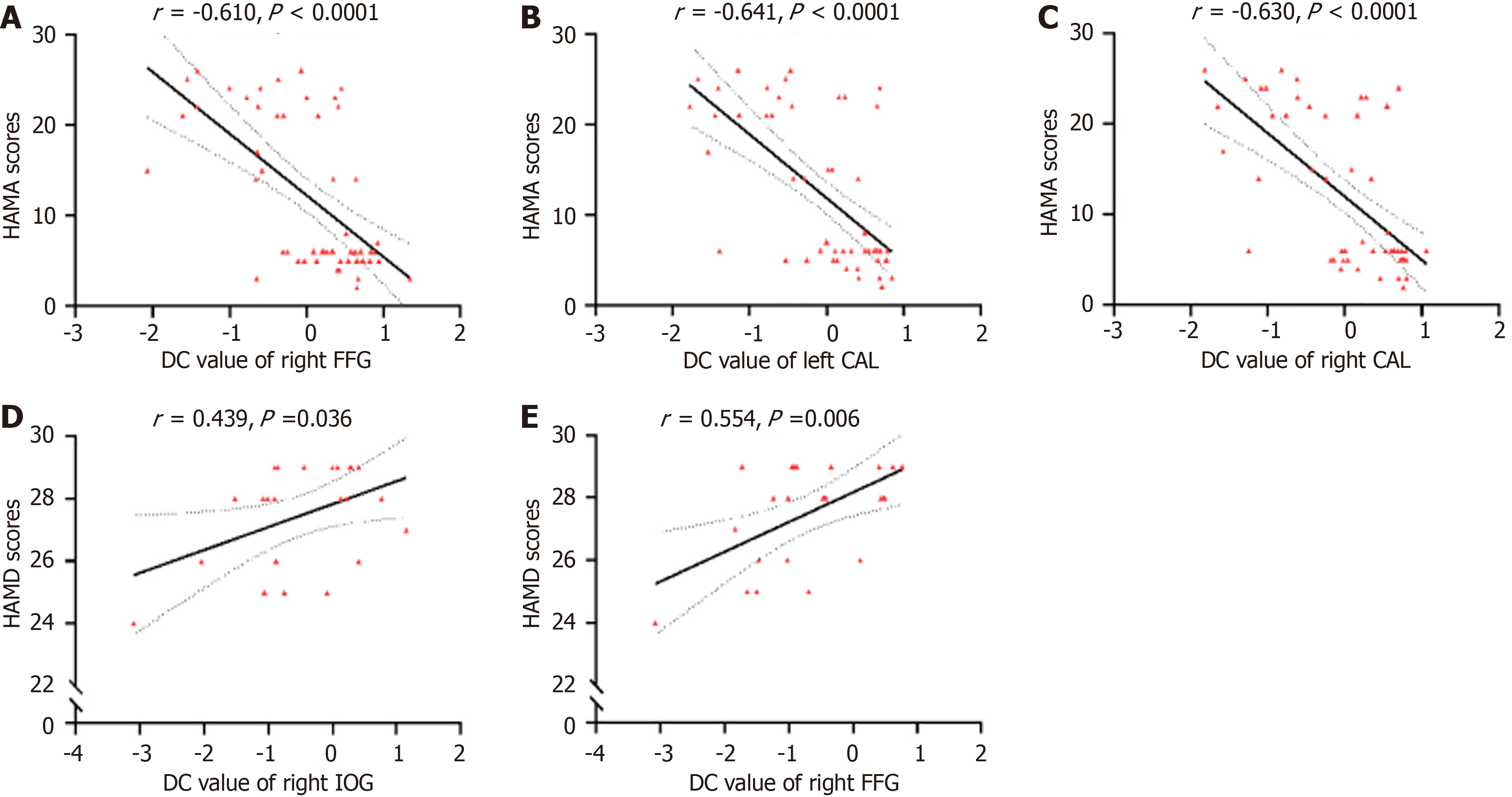

No significant correlation was noted between the DC values of 10 brain regions and clinical characteristics in the nonanxious MDD group. In the anxious MDD group, the DC values of the right IOG (r = 0.439, P = 0.036) and right FFG

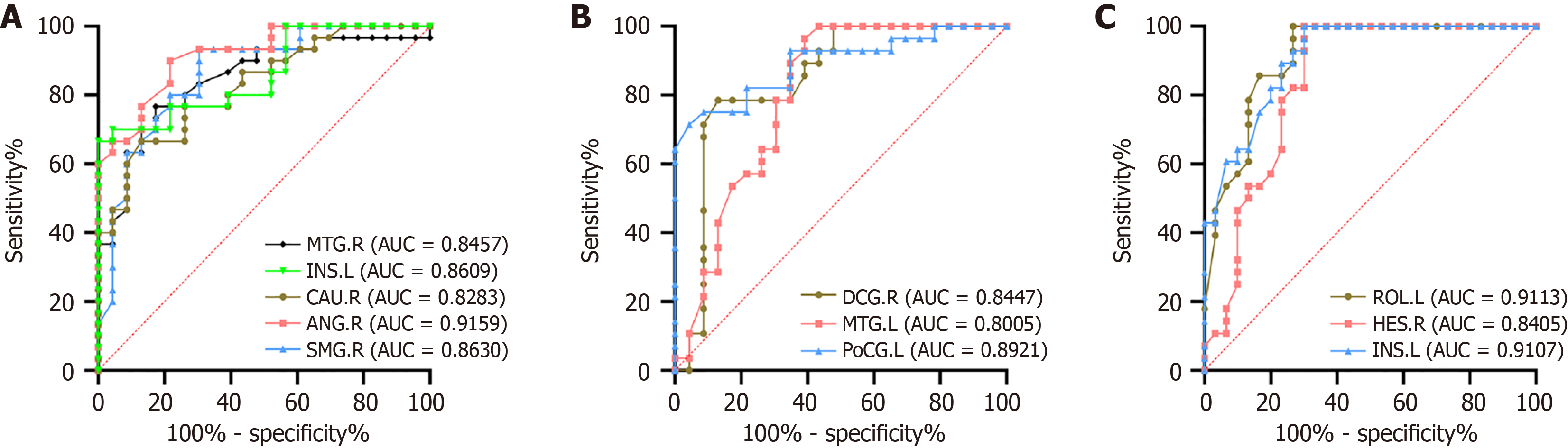

Figure 4 presents the ROC analysis results of 10 brain regions, as well as explains the ability of the analysis to distinguish the study groups. The DC values of the right FFG and bilateral CAL could potentially identify the anxious and nonanxious MDD groups, whereas the right IOG and FFG, left MFG, and IPAG could help in differentiating between anxious MDD patients and HCs. In addition, the bilateral cerebellum IX, right PCu, and right IFOG exhibited high sensitivity and specificity in differentiating nonanxious MDD from HCs. In the three groups, the DC values of the left CAL, MFG, and right PCu revealed the highest diagnostic value, while other brain regions also displayed good specificity. Of note, all area under the ROC curve (AUC) values were > 75% (Figure 4).

To the best of our knowledge, this study involves a novel investigation of the functional variations within the global brain network among patients with MDD, with or without comorbid anxiety. Precisely, this study examined variations in DC values within the brain network nodes at resting state. The findings revealed that the DC values of the bilateral CAL and right FFG were markedly lower in anxious MDD patients than in nonanxious MDD patients. Compared with HCs, anxious MDD patients revealed markedly reduced DC values of the right IOG and FFG, whereas markedly increased DC values of the left MFG and IPAG. In addition, nonanxious MDD patients exhibited elevated DC values in the bilateral cerebellum IX, right PCu, and right IFOG. Meanwhile, the DC values of the right IOG and FFG in anxious MDD patients positively correlated with HAMD scores. In MDD patients, the DC values of the right FFG and bilateral CAL demonstrated a strong negative correlation with HAMA scores. Besides, the ROC curve analysis revealed that anomalous DC values in the left CAL, MFG, and right PCu had high diagnostic and efficient potential (AUC > 0.8).

The frontal lobe regulates the motor function, cognitive function, mental activity, and sense of smell[36]. The right IFG is an integral component of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex regulates emotions and cognition; therefore, any damage to this area could lead to negative emotions, cognitive decline, and other manifestations[37]. Arguably, the putative mirror neuron system, which encompasses the IFG and inferior parietal lobe (IPL), could be responsible for the troubled social lives of MDD patients[38-40]. Structural MRI studies have reported structural anomalies in depression-related regions of the white matter and GM in the IFG[41]. Atypical IFG activity correlates with cognitive performance in clinical mood disorders, primarily MDD, and related interpersonal and social impairments, but does not differentiate MDD subtypes[42-44]. Our study demonstrated markedly elevated DC values of the right IFOG in nonanxious MDD patients compared with HCs, which counters previous studies[11]. Prior research reported lower GM volumes in the right IFG and orbitofrontal gyrus of anxious MDD patients than those of nonanxious MDD patients and HCs[45]. We hypothesized that an anomalous right IFG could underlie the neuropathology of all depression types[46] and that the difference could be attributable to the sample size. The MFG is essential in the regulation and allocation of attention[47]. A study reported markedly increased ALFF and ReHo of the right PCu and left MFG in patients with subclinical depression compared with HCs[48]. Corroborating their findings, the anxious MDD group in our study had markedly higher DC values in the left MFG than the nonanxious MDD group; in an anxious MDD state, perhaps, this brain region may increase the intensity of attentional modulation and allocation to control excessive anxiety and chaotic thinking, thereby accounting for higher DC values. This further suggests the key role that the left MFG plays in the neural mechanisms of anxious MDD.

The subjective perception of an action’s future state is generated by both the parietal cortex and the cerebellum[49,50]. A high correlation has been reported between the IPL and apathy core symptom of MDD[51]. Arguably, global-brain FC in the IPL is a substantial functional change in MDD patients[52]. In addition, aberrant functional activity of neurons in the left IPAG, which strongly correlates with the salience network and default mode network (DMN), has been detected in adult patients with MDD across all age groups. Furthermore, patients of all age groups exhibited aberrant ReHo compared with suitably matched HCs[53,54]. Perhaps, the IPAG could have created new connections with specific brain regions in the DMN, and this realignment of connections across the network would be responsible for elevated DC values.

Our study noted elevated DC values within the left IPAG of the anxious MDD group compared with the HC group, suggesting that the pathophysiology of anxious MDD might entail malfunction in these regions. Nevertheless, this decline was only noted in the anxious MDD group, not in the nonanxious MDD group compared with the HC group. As a part of DMN, the PCC/PCu is engaged in memory modulation and plays a role in outlook, situation retrieval, and mental scene construction[55]. Prior research has reported decreased functional networks, atypical FC, elevated overall brain correlation, and substantial anomalies in ReHo in the PCu of MDD patients[56-60]. Only the nonanxious MDD group in our study exhibited a statistically significant increase in DC values in the right PCu compared with the HC group. These findings suggest that anomalies in the right PCu could be specific to nonanxious MDD and possibly related to autobiographical memory, such as low self-evaluation, excessive recall of negative events, and weak autobiographical integration ability[61], which could also correlate with the clinical manifestations of MDD[62].

MDD patients reportedly have negative emotional bias mediated by the right FFG[63], and one of the neural components of the MDD classifier is the functional connection between the FFG and the occipital gyrus[64]. Several functional imaging studies have reported abnormal ReHo[65], ALFF[66], and FC[67] in the right FFG of MDD patients compared with HCs. Corroborating prior experimental results, this study noted that the DC values of the right FFG in the anxious MDD group were markedly lower than those of the HC or nonanxious MDD group. Notably, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) closely correlates with emotion regulation[68]. Therefore, dysfunction of the 5-HT system could be severer in anxious MDD patients, resulting in less efficient connectivity between the FFG brain area and other brain areas and reduced DC values. Therefore, the declined DC values of the right FFG could be a potential neuroimaging diagnostic tool for differentiating between anxious and nonanxious MDD, thereby simplifying the identification and assessment of people with anxious MDD. Meanwhile, this study demonstrated that DC values of the right IOG and FFG positively correlated with HAMD scores in the anxious MDD group, indicating that in anxious MDD patients, the higher the DC values of the right FFG and right IOG, the higher the compensatory repair of the pertinent brain regions, and the more susceptible they are to develop depressive mood. Thus, changes in the FFG could correlate with emotional perception and negative emotions. Under the impact of anxiety factors, the functional changes in the FFG of anxious MDD patients could contribute to the neuropathologic process underlying the social withdrawal symptoms in MDD. Moreover, the DC values of the right FFG and bilateral CAL exhibited a strong negative correlation with HAMA scores in MDD patients, suggesting that the lower the DC values of the right FFG and bilateral CAL and the severer the damage to the pertinent brain regions in all MDD patients, the more susceptible they are to experience anxiety. Hence, these two correlations could signify differences in emotional processing between anxious and nonanxious MDD patients.

The brain’s visual recognition network comprises the occipital gyrus and FFG. The occipital gyrus is mainly responsible for processing visual stimulation, including facial emotional awareness[69] and working memory[70]. Meanwhile, the CAL is a vital region of the cerebral cortex responsible for visual information processing[71]. Besides, the superior occipital gyrus and IOG play key roles in visual processing, regulating multiple visual processes[72,73]. How

The cerebellum is closely related to some brain regions like the prefrontal, superior temporal, and limbic cortices[79,80]; thus, any disturbance in the way that these circuits are regulated could alter people’s personality and lead to mild anomie and lessened executive function[81]. According to recent fMRI research, cerebellar topographic maps could map nonmotor processing, including nonmotor task processes and the DMN[82]. Reportedly, anomalies in cerebellar IX correlate with depression in PD patients[83], essential tremor patients[84], and melancholy MDD patients[52].

Our study discovered that, compared with the HC group, the nonanxious MDD group had higher DC values in the bilateral cerebellum IX, although no discernible difference was observed in DC values in this brain area between the other two groups. We postulated that the function of the bilateral cerebellum IX in anxious MDD patients was reinstated or altered in some way, corroborating previous studies reporting activation in several brain areas similar to HCs and patients with generalized anxiety and major depression comorbidities[85]. The elevated DC values in the bilateral cerebellum IX could depict a compensatory effort to offset emotional and cognitive imbalances during task activation or a dedifferentiation that signifies reduced recruitment of specialized neural mechanisms[86,87]. Hence, the investigation of such compensatory mechanisms warrants additional experimental data for illustration and exhaustive analysis, which we might cover in future research.

Furthermore, our study evaluated the discriminative capacity of DC values in corresponding brain regions for differentiating between anxious and nonanxious MDD using the ROC analysis. As shown in Figure 4, the left CAL’s AUC was the highest (AUC = 86.38%), signifying that the left CAL’s DC value was a highly specific and sensitive marker for distinguishing between anxious and nonanxious MDD. Besides, the left MFG (AUC = 84.78%) and right PCu (AUC = 89.17%) were the best indicators for distinguishing anxious and nonanxious MDD from HCs. When the DC value in the left CAL markedly declines in MDD patients, it could provide clinicians with crucial clues to more precisely identify and assess people with anxious MDD. By monitoring this brain region, it is possible to identify the presence of anxiety symptoms at an early stage, offering a strong basis for articulating a personalized treatment plan. Nevertheless, further research integrating FC and regional brain activity is needed to elucidate the functional anomalies of neural networks in anxious MDD. Moreover, prospective cohort studies are needed that focus on people with MDD at risk of developing anxious MDD. Hence, future research should explore the potential correlation between aberrant baseline spontaneous neural activity in the brain and the occurrence of anxious mood, enabling the timely detection and personalized treatment measures to slow down the advancement of MDD.

However, this research is not without limits. First, a longitudinal design was not adopted that could have explained how therapy affects DC values in specific brain regions. Second, nonanxious MDD patients were not categorized further owing to a somewhat small sample size. Third, clinical symptoms, such as cognitive impairments, were not thoroughly evaluated; instead, HAMD and HAMA scores were used to assess patients’ depression and anxiety symptoms. Finally, the study was restricted to a specific technique of data analysis. Hence, additional long-term multimodal fMRI research is needed to explicate the etiology and therapeutic approach.

This study demonstrates that MDD patients exhibit higher levels of anxiety when the DC values are lower in the right FFG and bilateral CAL. Being the first study to explore changed DC values between anxious and nonanxious MDD patients, the findings align with a biological foundation for anxious MDD, which is attributable to anomalies in the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital cortical function, along with specific areas of the cerebellum. Overall, this study furthers our understanding of the brain connections between anxiety and MDD, offering distinct perspectives on the neurobiology and neuropathology of anxious MDD. Notably, the results of this study can be used as an image-based biomarker for diagnosing and evaluating anxious MDD.

The authors would like to thank the mental health professionals and subjects who were involved in the project.

| 1. | Gaspersz R, Nawijn L, Lamers F, Penninx BWJH. Patients with anxious depression: overview of prevalence, pathophysiology and impact on course and treatment outcome. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31:17-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Nakonezny PA, Morris DW, Greer TL, Byerly MJ, Carmody TJ, Grannemann BD, Bernstein IH, Trivedi MH. Evaluation of anhedonia with the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) in adult outpatients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;65:124-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Xiao L, Zhou JJ, Feng Y, Zhu XQ, Wu WY, Hu YD, Niu YJ, Hu J, Wang XY, Gao CG, Zhang N, Fang YR, Liu TB, Jia FJ, Feng L, Wang G. Does early and late life depression differ in residual symptoms, functioning and quality of life among the first-episode major depressive patients. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;47:101843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhong Y, Huang J, Zhang W, Li S, Gao Y. Addressing psychosomatic issues after lifting the COVID-19 policy in China: A wake-up call. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;82:103517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhou E, Ma S, Kang L, Zhang N, Wang P, Wang W, Nie Z, Chen M, Xu J, Sun S, Yao L, Xiang D, Liu Z. Psychosocial factors associated with anxious depression. J Affect Disord. 2023;322:39-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Häberling I, Baumgartner N, Emery S, Keller P, Strumberger M, Nalani K, Schmeck K, Erb S, Bachmann S, Wöckel L, Müller-Knapp U, Contin-Waldvogel B, Rhiner B, Walitza S, Berger G. Anxious depression as a clinically relevant subtype of pediatric major depressive disorder. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2019;126:1217-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | van Loo HM, Cai T, Gruber MJ, Li J, de Jonge P, Petukhova M, Rose S, Sampson NA, Schoevers RA, Wardenaar KJ, Wilcox MA, Al-Hamzawi AO, Andrade LH, Bromet EJ, Bunting B, Fayyad J, Florescu SE, Gureje O, Hu C, Huang Y, Levinson D, Medina-Mora ME, Nakane Y, Posada-Villa J, Scott KM, Xavier M, Zarkov Z, Kessler RC. Major depressive disorder subtypes to predict long-term course. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31:765-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, Balasubramani GK, Wisniewski SR, Carmin CN, Biggs MM, Zisook S, Leuchter A, Howland R, Warden D, Trivedi MH. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:342-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 701] [Cited by in RCA: 655] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gili M, García Toro M, Armengol S, García-Campayo J, Castro A, Roca M. Functional impairment in patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid anxiety disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:679-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lv D, Ou Y, Xiao D, Li H, Liu F, Li P, Zhao J, Guo W. Identifying major depressive disorder with associated sleep disturbances through fMRI regional homogeneity at rest. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Peng W, Jia Z, Huang X, Lui S, Kuang W, Sweeney JA, Gong Q. Brain structural abnormalities in emotional regulation and sensory processing regions associated with anxious depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;94:109676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huang Y, Wang W, Hei G, Yang Y, Long Y, Wang X, Xiao J, Xu X, Song X, Gao S, Shao T, Huang J, Wang Y, Zhao J, Wu R. Altered regional homogeneity and cognitive impairments in first-episode schizophrenia: A resting-state fMRI study. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;71:103055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jin S, Liu W, Hu Y, Liu Z, Xia Y, Zhang X, Ding Y, Zhang L, Xie S, Ma C, Kang Y, Hu Z, Cheng W, Yang Z. Aberrant functional connectivity of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and its age dependence in children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;82:103498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhuo C, Li G, Lin X, Jiang D, Xu Y, Tian H, Wang W, Song X. The rise and fall of MRI studies in major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Luo Q, Chen J, Li Y, Lin X, Yu H, Lin X, Wu H, Peng H. Cortical thickness and curvature abnormalities in patients with major depressive disorder with childhood maltreatment: Neural markers of vulnerability? Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;80:103396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liu CH, Ma X, Song LP, Fan J, Wang WD, Lv XY, Zhang Y, Li F, Wang L, Wang CY. Abnormal spontaneous neural activity in the anterior insular and anterior cingulate cortices in anxious depression. Behav Brain Res. 2015;281:339-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Li GZ, Liu PH, Zhang AX, Andari E, Zhang KR. A resting state fMRI study of major depressive disorder with and without anxiety. Psychiatry Res. 2022;315:114697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sporns O. Graph theory methods: applications in brain networks. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20:111-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Minati L, Varotto G, D'Incerti L, Panzica F, Chan D. From brain topography to brain topology: relevance of graph theory to functional neuroscience. Neuroreport. 2013;24:536-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Al-Zubaidi A, Heldmann M, Mertins A, Jauch-Chara K, Münte TF. Influences of Hunger, Satiety and Oral Glucose on Functional Brain Connectivity: A Multimethod Resting-State fMRI Study. Neuroscience. 2018;382:80-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Guo M, Ren Y, Yu H, Yang H, Cao C, Li Y, Fan G. Alterations in Degree Centrality and Functional Connectivity in Parkinson's Disease Patients With Freezing of Gait: A Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:582079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yang Y, Dong Y, Chawla NV. Predicting node degree centrality with the node prominence profile. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yu Y, Li Z, Lin Y, Yu J, Peng G, Zhang K, Jia X, Luo B. Depression Affects Intrinsic Brain Activity in Patients With Mild Cognitive Impairment. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Buckner RL, Sepulcre J, Talukdar T, Krienen FM, Liu H, Hedden T, Andrews-Hanna JR, Sperling RA, Johnson KA. Cortical hubs revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity: mapping, assessment of stability, and relation to Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1860-1873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2423] [Cited by in RCA: 2250] [Article Influence: 140.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Meng L, Zhang Y, Lin H, Mu J, Liao H, Wang R, Jiao S, Ma Z, Miao Z, Jiang W, Wang X. Abnormal hubs in global network as potential neuroimaging marker in generalized anxiety disorder at rest. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1075636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yang L, Jin C, Qi S, Teng Y, Li C, Yao Y, Ruan X, Wei X. Aberrant degree centrality of functional brain networks in subclinical depression and major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1084443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen F, Wang L, Ding Z. Alteration of whole-brain amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation and degree centrality in patients with mild to moderate depression: A resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1061359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yan H, Han Y, Shan X, Li H, Liu F, Zhao J, Li P, Guo W. Shared and distinctive dysconnectivity patterns underlying pure generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and comorbid GAD and depressive symptoms. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;170:225-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhu J, Xu C, Zhang X, Qiao L, Wang X, Zhang X, Yan X, Ni D, Yu T, Zhang G, Li Y. The changes in the topological properties of brain structural network based on diffusion tensor imaging in pediatric epilepsy patients with vagus nerve stimulators: A graph theoretical analysis. Brain Dev. 2021;43:97-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yu XM, Qiu LL, Huang HX, Zuo X, Zhou ZH, Wang S, Liu HS, Tian L. Comparison of resting-state spontaneous brain activity between treatment-naive schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Liu W, Fang P, Guo F, Qiao Y, Zhu Y, Wang H. Graph-Theory-Based Degree Centrality Combined with Machine Learning Algorithms Can Predict Response to Treatment with Antipsychotic Medications in Patients with First-Episode Schizophrenia. Dis Markers. 2022;2022:1853002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Deng W, Zhang B, Zou W, Zhang X, Cheng X, Guan L, Lin Y, Lao G, Ye B, Li X, Yang C, Ning Y, Cao L. Abnormal Degree Centrality Associated With Cognitive Dysfunctions in Early Bipolar Disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lin H, Xiang X, Huang J, Xiong S, Ren H, Gao Y. Abnormal degree centrality values as a potential imaging biomarker for major depressive disorder: A resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study and support vector machine analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:960294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zuo XN, Ehmke R, Mennes M, Imperati D, Castellanos FX, Sporns O, Milham MP. Network centrality in the human functional connectome. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22:1862-1875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 725] [Cited by in RCA: 890] [Article Influence: 63.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Song XW, Dong ZY, Long XY, Li SF, Zuo XN, Zhu CZ, He Y, Yan CG, Zang YF. REST: a toolkit for resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging data processing. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1442] [Cited by in RCA: 1612] [Article Influence: 115.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Badre D, Nee DE. Frontal Cortex and the Hierarchical Control of Behavior. Trends Cogn Sci. 2018;22:170-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yin JB, Liang SH, Li F, Zhao WJ, Bai Y, Sun Y, Wu ZY, Ding T, Sun Y, Liu HX, Lu YC, Zhang T, Huang J, Chen T, Li H, Chen ZF, Cao J, Ren R, Peng YN, Yang J, Zang WD, Li X, Dong YL, Li YQ. dmPFC-vlPAG projection neurons contribute to pain threshold maintenance and antianxiety behaviors. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:6555-6570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Rizzolatti G, Craighero L. The mirror-neuron system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:169-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4715] [Cited by in RCA: 3831] [Article Influence: 182.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Schreiter S, Pijnenborg GH, Aan Het Rot M. Empathy in adults with clinical or subclinical depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Somani A, Singh AK, Gupta B, Nagarkoti S, Dalal PK, Dikshit M. Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress in Major Depressive Disorder: A Case Control Study. Brain Sci. 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Yang X, Ma X, Huang B, Sun G, Zhao L, Lin D, Deng W, Li T, Ma X. Gray matter volume abnormalities were associated with sustained attention in unmedicated major depression. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;63:71-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | MacNamara A, Klumpp H, Kennedy AE, Langenecker SA, Phan KL. Transdiagnostic neural correlates of affective face processing in anxiety and depression. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34:621-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Satterthwaite TD, Cook PA, Bruce SE, Conway C, Mikkelsen E, Satchell E, Vandekar SN, Durbin T, Shinohara RT, Sheline YI. Dimensional depression severity in women with major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder correlates with fronto-amygdalar hypoconnectivty. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:894-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Suh JS, Schneider MA, Minuzzi L, MacQueen GM, Strother SC, Kennedy SH, Frey BN. Cortical thickness in major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;88:287-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Abraham E, Wang Y, Svob C, Semanek D, Gameroff MJ, Shankman SA, Weissman MM, Talati A, Posner J. Organization of the social cognition network predicts future depression and interpersonal impairment: a prospective family-based study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47:531-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Yang X, Su Y, Yang F, Song Y, Yan J, Luo Y, Zeng J. Neurofunctional mapping of reward anticipation and outcome for major depressive disorder: a voxel-based meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2022;1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Chang J, Zhang M, Hitchman G, Qiu J, Liu Y. When you smile, you become happy: evidence from resting state task-based fMRI. Biol Psychol. 2014;103:100-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Zhang B, Qi S, Liu S, Liu X, Wei X, Ming D. Altered spontaneous neural activity in the precuneus, middle and superior frontal gyri, and hippocampus in college students with subclinical depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Desmurget M, Grafton S. Forward modeling allows feedback control for fast reaching movements. Trends Cogn Sci. 2000;4:423-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 882] [Cited by in RCA: 871] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Sirigu A, Duhamel JR, Cohen L, Pillon B, Dubois B, Agid Y. The mental representation of hand movements after parietal cortex damage. Science. 1996;273:1564-1568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 558] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Kos C, van Tol MJ, Marsman JB, Knegtering H, Aleman A. Neural correlates of apathy in patients with neurodegenerative disorders, acquired brain injury, and psychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;69:381-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Fu X, Yang X, Cui X, Liu F, Li H, Yan M, Xie G, Guo W. Overlapping and segregated changes of functional hubs in melancholic depression and non-melancholic depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;154:123-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Sun JF, Chen LM, He JK, Wang Z, Guo CL, Ma Y, Luo Y, Gao DQ, Hong Y, Fang JL, Xu FQ. A Comparative Study of Regional Homogeneity of Resting-State fMRI Between the Early-Onset and Late-Onset Recurrent Depression in Adults. Front Psychol. 2022;13:849847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Yu F, Fang H, Zhang J, Wang Z, Ai H, Kwok VPY, Fang Y, Guo Y, Wang X, Zhu C, Luo Y, Xu P, Wang K. Individualized prediction of consummatory anhedonia from functional connectome in major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2022;39:858-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Costigan AG, Umla-Runge K, Evans CJ, Hodgetts CJ, Lawrence AD, Graham KS. Neurochemical correlates of scene processing in the precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex: A multimodal fMRI and (1) H-MRS study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40:2884-2898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Abdallah CG, Averill LA, Collins KA, Geha P, Schwartz J, Averill C, DeWilde KE, Wong E, Anticevic A, Tang CY, Iosifescu DV, Charney DS, Murrough JW. Ketamine Treatment and Global Brain Connectivity in Major Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:1210-1219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Fan H, Yang X, Zhang J, Chen Y, Li T, Ma X. Analysis of voxel-mirrored homotopic connectivity in medication-free, current major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2018;240:171-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Schneider I, Schmitgen MM, Bach C, Listunova L, Kienzle J, Sambataro F, Depping MS, Kubera KM, Roesch-Ely D, Wolf RC. Cognitive remediation therapy modulates intrinsic neural activity in patients with major depression. Psychol Med. 2020;50:2335-2345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Shi Y, Li J, Feng Z, Xie H, Duan J, Chen F, Yang H. Abnormal functional connectivity strength in first-episode, drug-naïve adult patients with major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020;97:109759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Sun H, Luo L, Yuan X, Zhang L, He Y, Yao S, Wang J, Xiao J. Regional homogeneity and functional connectivity patterns in major depressive disorder, cognitive vulnerability to depression and healthy subjects. J Affect Disord. 2018;235:229-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Maddock RJ, Garrett AS, Buonocore MH. Remembering familiar people: the posterior cingulate cortex and autobiographical memory retrieval. Neuroscience. 2001;104:667-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Ressler KJ, Mayberg HS. Targeting abnormal neural circuits in mood and anxiety disorders: from the laboratory to the clinic. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1116-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 805] [Cited by in RCA: 732] [Article Influence: 40.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Surguladze S, Brammer MJ, Keedwell P, Giampietro V, Young AW, Travis MJ, Williams SC, Phillips ML. A differential pattern of neural response toward sad versus happy facial expressions in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:201-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 458] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Ichikawa N, Lisi G, Yahata N, Okada G, Takamura M, Hashimoto RI, Yamada T, Yamada M, Suhara T, Moriguchi S, Mimura M, Yoshihara Y, Takahashi H, Kasai K, Kato N, Yamawaki S, Seymour B, Kawato M, Morimoto J, Okamoto Y. Primary functional brain connections associated with melancholic major depressive disorder and modulation by antidepressants. Sci Rep. 2020;10:3542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Yan M, He Y, Cui X, Liu F, Li H, Huang R, Tang Y, Chen J, Zhao J, Xie G, Guo W. Disrupted Regional Homogeneity in Melancholic and Non-melancholic Major Depressive Disorder at Rest. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:618805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Liu F, Guo W, Liu L, Long Z, Ma C, Xue Z, Wang Y, Li J, Hu M, Zhang J, Du H, Zeng L, Liu Z, Wooderson SC, Tan C, Zhao J, Chen H. Abnormal amplitude low-frequency oscillations in medication-naive, first-episode patients with major depressive disorder: a resting-state fMRI study. J Affect Disord. 2013;146:401-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Sacu S, Wackerhagen C, Erk S, Romanczuk-Seiferth N, Schwarz K, Schweiger JI, Tost H, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Heinz A, Razi A, Walter H. Effective connectivity during face processing in major depression - distinguishing markers of pathology, risk, and resilience. Psychol Med. 2023;53:4139-4151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Liu Y, Zhao J, Guo W. Emotional Roles of Mono-Aminergic Neurotransmitters in Major Depressive Disorder and Anxiety Disorders. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Tao H, Guo S, Ge T, Kendrick KM, Xue Z, Liu Z, Feng J. Depression uncouples brain hate circuit. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:101-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Garrett A, Kelly R, Gomez R, Keller J, Schatzberg AF, Reiss AL. Aberrant brain activation during a working memory task in psychotic major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:173-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Liu Y, Shi G, Li M, Xing H, Song Y, Xiao L, Guan Y, Han Z. Early Top-Down Modulation in Visual Word Form Processing: Evidence From an Intracranial SEEG Study. J Neurosci. 2021;41:6102-6115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | de Haas B, Sereno MI, Schwarzkopf DS. Inferior Occipital Gyrus Is Organized along Common Gradients of Spatial and Face-Part Selectivity. J Neurosci. 2021;41:5511-5521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Hu B, Yu Y, Dai YJ, Feng JH, Yan LF, Sun Q, Zhang J, Yang Y, Hu YC, Nan HY, Zhang XN, Zheng Z, Qin P, Wei XC, Cui GB, Wang W. Multi-modal MRI Reveals the Neurovascular Coupling Dysfunction in Chronic Migraine. Neuroscience. 2019;419:72-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Yao Z, Zou Y, Zheng W, Zhang Z, Li Y, Yu Y, Zhang Z, Fu Y, Shi J, Zhang W, Wu X, Hu B. Structural alterations of the brain preceded functional alterations in major depressive disorder patients: Evidence from multimodal connectivity. J Affect Disord. 2019;253:107-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Zaninotto L, Solmi M, Veronese N, Guglielmo R, Ioime L, Camardese G, Serretti A. A meta-analysis of cognitive performance in melancholic versus non-melancholic unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;201:15-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Zheng LJ, Yang GF, Zhang XY, Wang YF, Liu Y, Zheng G, Lu GM, Zhang LJ, Han Y. Altered amygdala and hippocampus effective connectivity in mild cognitive impairment patients with depression: a resting-state functional MR imaging study with granger causality analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:25021-25031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Zhang Y, Cui X, Ou Y, Liu F, Li H, Chen J, Zhao J, Xie G, Guo W. Differentiating Melancholic and Non-melancholic Major Depressive Disorder Using Fractional Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuations. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:763770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Hu X, Song X, Yuan Y, Li E, Liu J, Liu W, Liu Y. Abnormal functional connectivity of the amygdala is associated with depression in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30:238-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Li H, Kepinska O, Caballero JN, Zekelman L, Marks RA, Uchikoshi Y, Kovelman I, Hoeft F. Decoding the role of the cerebellum in the early stages of reading acquisition. Cortex. 2021;141:262-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | van Es DM, van der Zwaag W, Knapen T. Topographic Maps of Visual Space in the Human Cerebellum. Curr Biol. 2019;29:1689-1694.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Schmahmann JD, Sherman JC. The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain. 1998;121 ( Pt 4):561-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2064] [Cited by in RCA: 2153] [Article Influence: 79.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Habas C. Functional Connectivity of the Cognitive Cerebellum. Front Syst Neurosci. 2021;15:642225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Ma X, Su W, Li S, Li C, Wang R, Chen M, Chen H. Cerebellar atrophy in different subtypes of Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Sci. 2018;392:105-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Duan X, Fang Z, Tao L, Chen H, Zhang X, Li Y, Wang H, Li A, Zhang X, Pang Y, Gu M, Wu J, Lv F, Luo T, Cheng O, Luo J, Xiao Z, Fang W. Altered local and matrix functional connectivity in depressed essential tremor patients. BMC Neurol. 2021;21:68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Waugh CE, Hamilton JP, Chen MC, Joormann J, Gotlib IH. Neural temporal dynamics of stress in comorbid major depressive disorder and social anxiety disorder. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2012;2:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Hilber P. The Role of the Cerebellar and Vestibular Networks in Anxiety Disorders and Depression: the Internal Model Hypothesis. Cerebellum. 2022;21:791-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Kurth F, Thompson PM, Luders E. Investigating the differential contributions of sex and brain size to gray matter asymmetry. Cortex. 2018;99:235-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |