INTRODUCTION

Economic violence is a form of domestic violence in which women face financial control and manipulation by intimate partners[1], affecting both their finances and their access to the resources that money can provide[2,3]. The World Health Organization reports that approximately one in three women (30%) worldwide have experienced physical and/or sexual violence from partners or non-partners in their lifetime[4]. In addition, women between the ages of 15 and 49 who have been in a relationship have experienced economic violence from their intimate partner at least once. In Turkey, according to 2019 data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the prevalence of violence against women is 38%, meaning that nearly four out of 10 women face male violence during their lifetime[5]. This violence manifests itself through various forms of control over spending, bank accounts, and income, while also limiting access to essential resources such as technology and transportation, which are vital to maintaining employment and social connections[6,7]. The impact of economic violence extends to women’s access to, quality of, and affordability of health care, affecting both individual and community well-being[8]. In addition, this form of abuse can include the destruction of property and the deliberate withholding of contributions to household expenses[9].

This article explores how economic violence impacts women’s financial independence and examines its role in perpetuating broader patterns of gender inequality and economic instability. By analyzing the psychological, emotional, and health consequences, as well as the legal and social frameworks surrounding the issue, the article aims to highlight the challenges of identifying and addressing economic violence. The study also proposes recommendations and future directions for stakeholders at all levels to combat this form of coercion and work toward a more equitable society where gender norms and economic disparities no longer determine one’s prosperity and security.

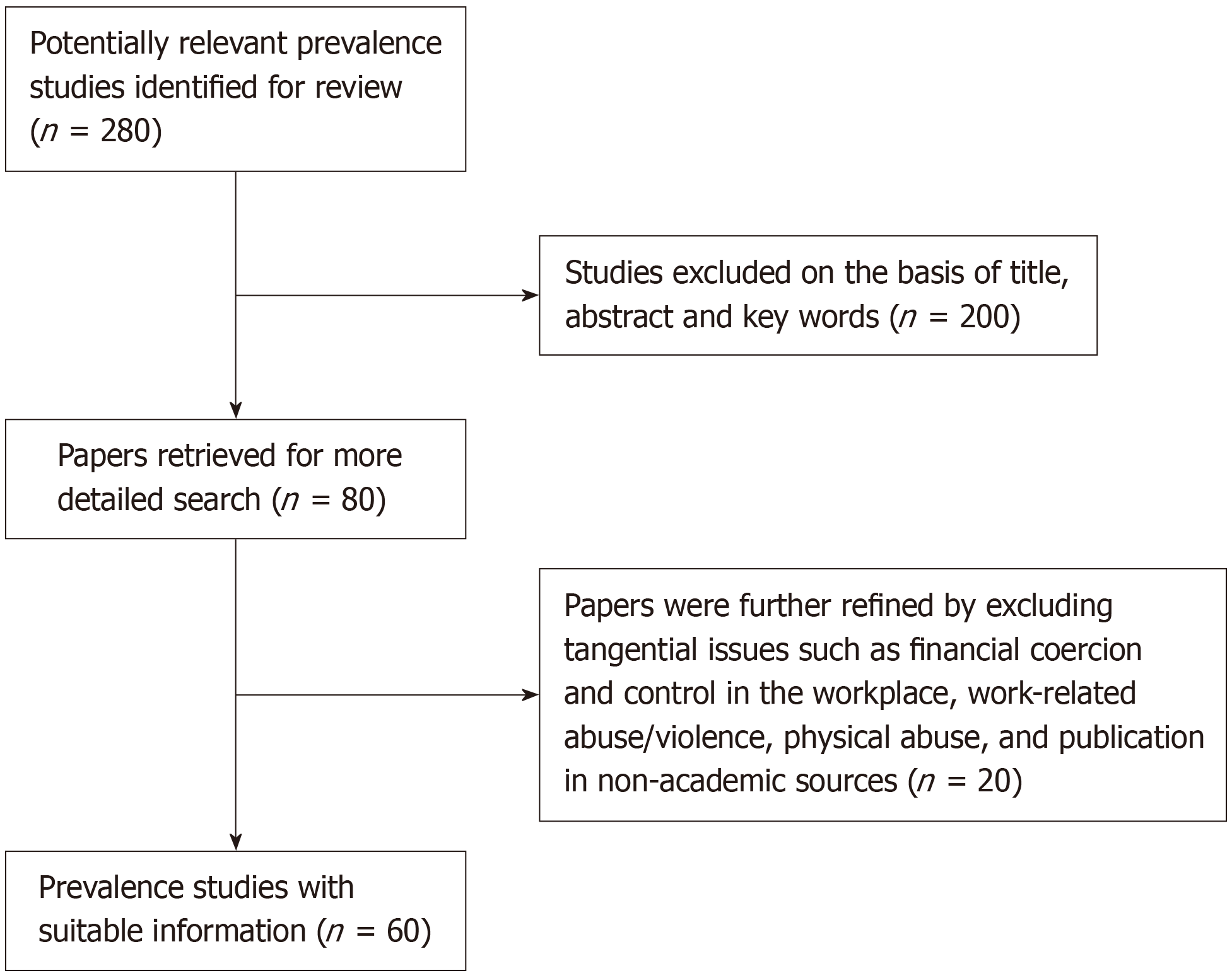

This article was conducted between June 2024 and October 2024 and included major academic databases in the fields of psychology, public policy, gender studies, women’s economic abuse, and economic violence. The search strategy utilized multiple scholarly databases, including Social Work Abstracts (EBSCO), Psychology Abstracts, Family and Women Studies Worldwide, Psychiatry Online, Psych INFO (including Psych ARTICLES), PubMed, Wiley, and Scopus. The search methodology used several key terms, specifically “financial abuse”, “economic abuse”, “intimate partner violence”, and “exploitation”, along with various combinations of these terms in conjunction with “women”. Given the large volume of initial results, we implemented specific inclusion criteria, limiting our analysis to peer-reviewed scientific literature published within the last decade and restricting the language of publication to Turkish and English. The preliminary database search yielded 280 articles addressing various forms of abuse, including sexual abuse, financial or economic violence, elder abuse, work-related abuse, intimate partner abuse, abuse and disability, and child abuse. Through inclusion criteria, this initial corpus was refined to 60 articles specifically related to violence against women. A subsequent in-depth analysis of 80 articles was conducted to determine whether economic or financial abuse was either the primary or secondary focus of the research. We further refined our selection by excluding articles that addressed tangential issues such as financial coercion and control in the workplace, work-related abuse, violence, physical abuse, or studies that did not explicitly include women or women as subjects. The final stage of our selection process resulted in the removal of twenty articles due to publication in non-academic sources and one research proposal, leaving a final corpus of 60 articles for comprehensive analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flow chart summarizing the literature review.

FROM A COMMUNITY MENTAL HEALTH PERSPECTIVE

Economic violence, characterized by the restriction and control of women’s access to financial resources such as employment, financial decision-making, or credit, is an important public health and community mental health concept that demonstrates how economic policies, practices, and conditions can cause harm to women and societies[10]. This form of violence is both a human rights violation and a pressing public health concern[11]. The contemporary manifestation of this violence presents a complex challenge that encompasses structural inequalities, social determinants of health, and the pervasive impact of economic policies on health outcomes[10]. This article aims to examine the key figures, impacts, and influential individuals within the field of economic violence from a public health and mental health perspective while exploring various aspects of this issue and proposing future recommendations and prevention strategies.

The historical underpinnings of economic violence are deeply embedded in systems of inequality, exploitation, and injustice[12,13], resulting from the unequal distribution of opportunities, resources, and power that perpetuate economic and social inequalities and ultimately lead to ongoing harm and suffering. These inequalities are manifested through limited access to health care, housing, employment, and education, as well as discriminatory practices and policies that disproportionately affect marginalized communities[13]. Research indicates a growing need to implement multidimensional approaches that provide concrete support and women-centered responses to reported cases of economic abuse, while also developing policies to improve socio-economic equality and expand economic opportunities for women[13,14]. Prominent figures in this field include academics, community-based organizations, policymakers, and health professionals who have dedicated their efforts to raising awareness of the social determinants of health, advocating for policies that address economic disparities, and promoting health equity. The consequences of economic violence are multifaceted and extensive. Economic inequalities are strongly associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, including increased rates of premature mortality, chronic disease, and mental illness[15]. These inequalities are exacerbated by social factors such as discrimination and sexism, which deepen the marginalization of vulnerable populations[15,16].

FORMS OF ECONOMIC VIOLENCE

Economic violence manifests itself in various forms that systematically undermine the financial independence of victims.

Income sabotage

Abusers may use tactics designed to disrupt the victim’s source of income, such as preventing the victim from going to work. Such tactics also include sabotaging their employment or interfering with their work performance through unannounced visits and excessive communication[9].

Resource control

Abusers often exert control over how victims’ access and use their financial resources. This includes controlling bank accounts, cash, and credit/debit card use. Often, the perpetrator will insist that financial assets be held solely in his or her name[8].

Work-related abuse

This form of violence involves deliberate actions to interfere with the victim’s ability to earn an income. Examples include forcing them to quit their job or preventing them from seeking employment[17].

Coerced debt

Abusers may force victims to make unauthorized credit transactions, which can damage the victim’s credit and affect the victim’s ability to secure employment or housing in the future. Common tactics include applying for loans or credit cards in the victim’s name without the victim’s knowledge or consent[18].

Withholding necessities

Gender-based economic violence includes acts such as withholding basic necessities such as medical care, clothing, and food. In addition, refusal to pay legally mandated alimony or child support is considered a form of abuse in this context[19].

Destructive litigation

Perpetrators of economic violence may repeatedly initiate costly legal actions as a method of psychological harassment, further depleting the victim’s economic resources[20]. Economic violence not only limits victims’ financial autonomy, as has been extensively documented in the literature but also limits their ability to escape abusive situations, thereby perpetuating their dependence on the abuser. This control extends beyond financial exploitation and affects the victim’s overall safety and well-being.

PREVALENCE AND STATISTICS

Global statistics

Compelling evidence underscores that gender-based economic violence is a widespread problem, affecting individuals across six continents, with women disproportionately affected. According to a 2023 United Nations report, approximately one in three women over the age of 15 have experienced sexual and/or physical violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime[21]. Research shows that countries with the highest prevalence of gender-based violence, including economic abuse, are Bangladesh, Jordan, Nigeria, Burundi, Uganda, Cameroon, Oman, Senegal, and Yemen[11,22]. Conversely, Northern European countries, Malta, and Canada report the lowest levels of gender-based violence, including economic abuse[11]. These findings highlight the global prevalence of violence against women and underscore the urgent need for comprehensive strategies to address all forms of violence, including economic violence.

Regional variations

The prevalence of economic violence varies widely and is influenced by legal, cultural, and economic factors. In the World Health Organization’s African region and the Americas report, estimates of lifetime intimate partner violence (IPV) range from 33% to 25%[4]. In India, economic violence is particularly prevalent, with women in states such as Maharashtra and Rajasthan often subjected to economic exploitation by their in-laws or husbands[23]. These findings highlight significant regional disparities and underscore the need for targeted interventions that take into account the specific cultural, economic, and social contexts of each region.

IMPACT ON WOMEN’S FINANCIAL INDEPENDENCE

Employment sabotage

Employment sabotage is a critical dimension of economic violence that severely undermines women’s financial independence[24]. Perpetrators often prevent victims from working or earning an income. This includes demanding that the victim quit her job, which increases her financial dependency. In addition, preventing victims from seeking employment or attending job interviews further isolates them from economic opportunities and independence. Intimate partner employment sabotage includes behaviors by partners aimed at obstructing employment or other sources of income, such as disability benefits and child support[25-28]. Despite its significant consequences, awareness of economic violence remains limited. The literature highlights the lack of empirical evidence on survivors’ economic self-sufficiency both during and after abusive relationships[6,29,30]. A critical reason for the minimal research attention given to economic violence, in contrast to sexual and psychological violence, is the lack of standardized tools to measure and assess economic abuse[6,31,32]. A notable tool, the Scale of Economic Abuse, was developed and later refined to assess economic abuse[33]. Results from the administration of Scale of Economic Abuse indicated that 100% of the women studied experienced psychological abuse, 98% experienced economic abuse, and 98% experienced physical abuse. The data also showed that higher levels of economic abuse correlated with higher levels of debt among victims. In addition, abusers often exploit victims’ financial resources for their benefit, exacerbating victims’ financial burdens[33]. This perpetuates a vicious cycle of economic dependence and vulnerability. Recognizing and addressing the prevalence of economic violence is essential to empowering women to control and access economic resources, ultimately promoting economic self-efficacy and improving their physical and mental health.

Control of financial resources

One of the primary mechanisms of economic violence is the control of financial resources. Perpetrators dictate when and how victims can access credit cards, money, or bank accounts, often forcing them to relinquish financial assets or instruments[34]. This form of control goes beyond immediate financial restrictions and has long-term consequences. For example, the inability to save money or access credit can leave victims in a precarious financial situation, unable to meet basic needs or secure stable housing[34]. The far-reaching effects of such financial control highlight the significant barriers victims face in rebuilding their lives and achieving independence.

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND EMOTIONAL CONSEQUENCES

Depression and anxiety

Economic violence is strongly associated with adverse mental health outcomes, particularly anxiety and depression[35,36]. There is substantial evidence that victims of economic violence are at increased risk for these conditions, with studies consistently showing a positive association between economic abuse and depressive symptoms[37,38].

Post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide

The psychological consequences of economic violence include serious conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidal ideation. Research shows a positive association between economic violence and these outcomes[39,40]. The stress caused by economic constraints and the coercive tactics used by perpetrators often result in chronic fear and a profound sense of helplessness[41]. These emotional states can lead victims to consider or attempt suicide, underscoring the severe psychological toll of economic violence. Addressing these issues requires comprehensive strategies that not only aim to prevent gender-based economic violence but also provide survivors with robust mental health support.

Physical health effects

Economic violence also has a significant impact on the physical health of victims, manifesting itself in various symptomatic forms across age groups[42]. Women aged 16-49 who experience economic violence are more likely to suffer from pelvic disorders and have difficulty maintaining a healthy weight[35]. In addition, economic violence often leads to food insecurity because financial resources are withheld, forcing victims to rely on abusive partners for basic nutritional needs[39,43]. Among older women aged 50-65, IPV has been associated with psychosomatic symptoms and gastrointestinal problems[25,26]. In addition, economic violence is associated with a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease and other physical health problems[43].

Future directions and recommendations

Significant knowledge gaps exist in the current literature on economic violence, particularly concerning the long-term financial and health consequences for victims. Research that provides deeper insights into the lasting effects of economic abuse and violence and the effectiveness of interventions remains severely lacking, as highlighted by Johnson et al[35]. Global statistics show that one-third of women and one-quarter of men in active relationships between the ages of “15” and “49” have experienced IPV[44-46]. In the United States, IPV affects 41% of women and 26% of men, with economic abuse present in 90% of these cases[47,48]. Research by Peraica et al[49] shows a significant gender gap in the duration of IPV exposure, with women remaining in financially abusive relationships significantly longer than men, who typically remain in such situations for no more than six months. Despite experiencing lower rates of IPV, male victims report significant challenges in accessing support services and often encounter dismissive attitudes when seeking help[50]. In addition, existing research highlights that within heterosexual relationships, the gender dynamics between abuser and victim significantly influence both the attribution of blame and the prevalence of economic abuse[44]. Research suggests that economic abuse perpetrated by female perpetrators against male victims is often minimized compared to abuse perpetrated by male perpetrators against female victims, with male victims typically facing higher levels of blame. These findings underscore the critical importance of examining how victim gender shapes societal attitudes toward survivors of economic abuse and suggest that future research initiatives should expand their scope to include male victims, thereby promoting a more comprehensive understanding of economic violence across demographic groups.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLICY AND PRACTICE

Effectively addressing economic violence requires its comprehensive integration into policy and legal frameworks[51]. Critical interventions include the strategic allocation of public funds to improve access to mental health services and childcare facilities. In addition, the implementation of specialized training programs focusing on economic abuse, domestic violence, and economic violence can significantly enhance society’s capacity to support victims[52]. Research indicates that broader educational initiatives and awareness programs focused on gender equity have significant potential to reduce instances of economic violence and alleviate financial stress within communities[53,54]. Substantial empirical evidence supports the protective role of women’s education and employment against economic violence[14,55]. By recognizing the profound health impact of economic violence against women, advocating for policies that address the underlying social determinants of health, and actively supporting health equity initiatives, society can move toward a more equitable and just framework for all its members.

STRENGTHENING SUPPORT SYSTEMS

The development of a comprehensive global support network that includes policymakers, financial institutions, and community organizations is a fundamental requirement. This network must foster collaborative relationships across multiple organizations to identify and address existing gaps in practices related to economic violence[56]. Addressing prevention methods and the root causes of economic disparities, including systemic racism, discrimination, and sexism remains critical to improving health outcomes and promoting equity. In addition to identifying these causal factors, developing and expanding theoretical knowledge about both perpetrators and victims of abuse is critical. Within this form of domestic violence, perpetrators typically exhibit a pattern of alternating violent, abusive, and apologetic behaviors, often accompanied by seemingly sincere promises of change and being pleasant[57]. Research shows that abusive behavior often follows a predictable cycle characterized by four distinct phases: (1) An initial tension-building period marked by growing anger and a communication breakdown; (2) An active phase of abuse; (3) A subsequent honeymoon period characterized by remorse and promises of reform, often accompanied by victim-blaming; and (4) A calm period during which the abuser acts as if no abuse has occurred, possibly offering gifts while the victim hopes for lasting behavioral change[58-60]. Moving forward, continued engagement with this issue, consideration of diverse perspectives, and interdisciplinary collaboration remain essential to addressing the complex challenges posed by economic violence against women from a public health perspective.

CONCLUSION

Economic violence remains a critical issue that requires urgent attention and action. This examination of gender-based economic violence and its profound impact on women has sought to uncover the harsh realities faced by many. The findings underscore that economic violence is not just a form of domestic abuse, but a pervasive social problem rooted in gender inequality that significantly undermines women’s financial independence. The study underscores the urgent need for comprehensive strategies aimed at promoting the long-term recovery and empowerment of survivors. Looking ahead, the need for a deeper understanding of economic violence, the development of robust legal frameworks, and the strengthening of supportive networks underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to effectively address this issue. Such collaboration is essential not only to provide survivors with the resources they need but also to support intervention studies that address gender-based violence and work towards creating an equitable society where all individuals can thrive free from exploitation.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: Türkiye

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Novelty: Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade A, Grade A, Grade A, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Alkan Ö; Feyissa GD; Xie XE S-Editor: Wei YF L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao YQ