Published online Feb 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i2.99996

Revised: December 4, 2024

Accepted: December 25, 2024

Published online: February 19, 2025

Processing time: 161 Days and 18.8 Hours

Sensitivity to stress is essential in the onset, clinical symptoms, course, and prognosis of major depressive disorder (MDD). Meanwhile, it was unclear how variously classified but connected stress-sensitivity variables affect MDD. We hypothesize that high-level trait- and state-related stress-sensitivity factors may have different cumulative effects on the clinical symptoms and follow-up outcomes of MDD.

To investigate how stress-sensitivity factors added up and affected MDD clinical symptoms and follow-up results.

In this prospective study, 281 MDD patients were enrolled from a tertiary care setting. High-level stress-sensitivity factors were classified as trait anxiety, state anxiety, perceived stress, and neuroticism, with a total score in the top quartile of the research cohort. The cumulative effects of stress-sensitivity factors on cog

Regarding high-level stress-sensitivity factors, 53.40% of patients had at least one at baseline, and 29.61% had two or more. Four high-level stress-sensitivity components had significant cumulative impacts on MDD symptoms at baseline (all P < 0.001). Perceived stress predicted the greatest effect sizes of state-related factors on depressive symptoms (partial η2 = 0.153; standardized β = 0.195; P < 0.05). The follow-up outcomes were significantly impacted only by the high-level trait-related components, mainly when it came to depressive symptoms and suicide risk, which were predicted by trait anxiety and neuroticism, respectively (partial η2 = 0.204 and 0.156; standardized β = 0.247 and 0.392; P < 0.05).

To enhance outcomes of MDD and lower the suicide risk, screening for stress-sensitivity factors and considering multifaceted measures, mainly focusing on trait-related ones, should be addressed clinically.

Core Tip: How variously classified but related stress-sensitivity factors affected major depressive disorder (MDD) was unknown. This prospective study looked at the relationship between stress-sensitivity variables and MDD in a novel way. We found that in MDD patients with high-level stress-sensitivity components, baseline symptoms were worse; state factors, especially perceived stress, had a greater influence on depressive symptoms. Patients with high trait factors at follow-up performed worse, especially in trait anxiety- and neuroticism-influenced depressive symptoms and suicide risk, respectively. Screening for stress-sensitivity factors-especially trait ones-should be prioritized to improve disease prognosis.

- Citation: Qin XM, Xu MQ, Qin YQ, Shao FZ, Ma MH, Ou WW, Lv GY, Zhang QQ, Chen WT, Zhao XT, Deng AQ, Xiong JT, Zeng LS, Peng YL, Huang M, Xu SY, Liao M, Zhang L, Li LJ, Ju YM, Liu J, Liu BS, Zhang Y. Cumulative effects of stress-sensitivity factors on depressive symptoms and suicide risk: A prospective study. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(2): 99996

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i2/99996.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i2.99996

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common psychiatric disorders around the world, with a lifetime prevalence of 3.4% in mainland China[1]. MDD is characterized by multidimensional symptoms, including sadness, anhedonia, loss of interest and motivation, social withdrawal, suicide ideation, and impaired cognitive function[2-5], leading to disability and functional impairment[6]. Numerous studies have demonstrated significant associations between stress and the onset, clinical manifestations, and follow-up outcomes of MDD[7-10].

Individual stress response is essential for adaptation, maintenance of homeostasis, and survival[11]. Therefore, studies have increasingly focused on the relationship between MDD and the sensitivity to stress, which suggests heightened stress sensitivity in patients with MDD[12]. In studies on depression, the term stress sensitivity, or stress reactivity, refers more specifically to the predisposition resulting from vulnerability mechanisms that are acquired or innate to react to lower levels of stress[13]. Heightened stress sensitivity in patients with MDD may be attributed to trait-related factors (e.g., personalities) and acquired contributors (e.g., stressful life events). Many studies have examined altered stress sensitivity in MDD using two strategies, i.e., investigating mood responses to negative and positive events and examining mood responses to minor stressors using ecological momentary assessment techniques such as the experience sampling method[14]. For instance, a study using the experience sampling method found that compared to healthy controls, patients with MDD exhibited significantly higher negative and lower positive affect in subjective appraisals of stress and daily life[15]. However, such methods mainly focus on subjects’ immediate response to stressors, which are also viewed as state-dependent stress sensitivity. Thus, the putative trait-like characteristics of stress sensitivity were overlooked in such studies[16].

Previous studies have used a variety of phenotypes (e.g., anxiety, nervousness, fear, tension, and negative emo

To date, little has been known about how differently categorized yet interrelated stress-sensitivity factors influence the symptoms and follow-up outcomes of MDD and whether their effects are different. Similar research questions have been explored by investigating the cumulative impact of multiple factors (including psychological ones) in complex physical diseases with multifactorial etiology[26].

The present study seeks to examine the cumulative effects of stress-sensitivity factors (neuroticism, trait anxiety, perceived stress, and state anxiety) on the clinical presentation and follow-up outcomes of MDD. These outcomes include depressive and anxiety symptoms, suicide risk, disability and functional impairment, and cognitive dysfunction. We propose the following hypotheses: (1) Elevated stress-sensitivity factors will exhibit cumulative effects on the clinical symptoms of MDD at baseline; (2) Elevated stress-sensitivity factors will also exert cumulative effects on follow-up outcomes of MDD; and (3) Trait- and state-related stress-sensitivity factors may influence different symptoms of MDD differently, both at baseline and during follow-up. This study aims to enhance our understanding of the relationship between stress sensitivity and MDD, offering valuable insights for improving psychiatric primary care interventions.

This study was performed in the inpatient and outpatient psychiatric departments of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. This hospital, located in central China, was established in 1958. It is a Class-A tertiary comprehensive hospital with the National Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders and the National Center for Mental Disorders. This hospital’s psychiatric specialty is one of the top three in China. As a result, the hospital sees patients from all over China, which is representative and vast and helps the study be more broadly applicable.

This prospective study recruited 281 patients with MDD from December 2019 to March 2023 based on the principle of convenience sampling. Patients meeting the following criteria were included: (1) Aged between 18 and 60 years; (2) Having current or previous clinical manifestations in line with a major depressive episode according to the 5th version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Psychiatric Disorders (DSM-5); (3) With a total score of > 7 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17)[27]; and (4) Willing to receive antidepressants prescribed by their psychiatrists for two months. Patients would be excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) With comorbid psychiatric disorders; (2) Currently pregnant or breastfeeding; and (3) With prior or present major medical conditions such as immune system diseases, endocrine and metabolic diseases, nervous system diseases, and a history of brain injury. Finally, a total of 206 participants were enrolled through the screening.

Upon enrollment, the participants were assessed by two trained professional psychiatrists independently based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5. Then, the participants were assessed using the HAMD-17 and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAMA) and were asked to complete a self-designed sociodemographic questionnaire and a variety of self-rating scales. After baseline assessments, all participants received first-line antidepressant therapy prescribed by their psychiatrists. Adjuvant therapies such as hypnotics and sedatives were used at the psychiatrists’ discretion. The psychiatrists regularly reviewed and adjusted the treatment, and patients were assessed on-site for clinical outcomes at the end of the 8-week follow-up. In total, 119 patients with MDD eventually finished the follow-up, except a few who were lost or dislodged because they switched to bipolar disorder, moved away from their initial residence, etc.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Clinical Medical Research Center, the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (MDD202011). All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Clinical symptoms and follow-up outcomes: Symptoms of depression and anxiety were assessed separately by HAMD-17 and HAMA. In the HAMD-17[28], 10 items were rated on a Likert scale (0-4), and others were rated on a Likert scale (0–2). The total score of HAMD-17 ranges from 0 to 54, with a score of less than 8 indicating no depression, 8-17 indicating mild depression, 18-24 indicating moderate depression, and ≥ 25 indicating severe depression. MDD patients with follow-up data were divided into a group with clinical remission (HAMD-17 < 8) and a group without clinical remission (HAMD-17 > 7) after eight weeks of treatment. The items of HAMA were rated on a Likert scale (0-4). The total score of HAMA ranges from 0-56, with a score of < 18 indicating mild anxiety, 18-24 indicating mild to moderate anxiety, and 25-30 indicating moderate to severe anxiety[29].

The Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSSI) was used to assess the suicide risk of the participants[30]. The BSSI includes 19 items rated on a Likert scale (0-2). The total score ranges from 0-38, with higher scores indicating higher suicide risk.

The self-rated Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) assessed functional impairment and disability in three major life domains: Work/studies, social life/Leisure activities, and family life/home responsibilities. In this scale, the items are visually presented as a horizontal line marked with both numbers (0 to 10) and verbal anchors (0 = not at all, 1–3 = mildly, 4–6 = moderately, 7–9 = markedly, and 10 = extremely). The total score ranges from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating more severe functional impairment[31].

The Perceived Deficits Questionnaire five-item version (PDQ-5) was used to measure cognitive dysfunction. Items are rated on a Likert scale (0-4), and their total score ranges from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating more severe cognitive dysfunction[32].

Stress-sensitivity factors: Trait-related stress-sensitivity factors included neuroticism and trait anxiety: (1) Neuroticism: 12 items from the NEO Five-Factor Inventory were used to assess neuroticism. The total score ranges from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating a higher level of neuroticism[33]; and (2) Trait anxiety: Trait anxiety was assessed using the 20-item Trait Anxiety Inventory (T-AI) from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, with higher scores indicating greater trait anxiety[34].

State-related stress-sensitivity factors included state anxiety and perceived stress: (1) State anxiety: State anxiety was assessed using the 20-item State Anxiety Inventory (S-AI) from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory[34], with higher scores indicating greater state anxiety; and (2) Perceived stress: The 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was used, with higher total scores indicating higher levels of perceived stress[32].

In the present study, patients with high-level stress-sensitivity factors were defined as those with scores in the highest quartile of the research cohort on each scale (i.e., Neuroticism score ≥ 48, T-AI score ≥ 65, S-AI score ≥ 62, and PSS score ≥ 28).

A priori analyses were performed using the G*Power 3.1 software during the study's design phase to determine the necessary sample size. A two-tailed test with a test level α of 0.05, a test power (1-β) of 0.9, and the number of predictors were set in G*Power 3.1 to ensure that an effect size of 0.3 (medium) was obtained, as linear multiple regression analysis is necessary to analyze the correlation of high-level stress-sensitivity factors and clinical outcomes. This resulted in a total sample size of 57 for the study. Participants in the top quartile of the research cohort on each scale (Neuroticism, T-AI, S-AI, and PSS) had high stress-sensitivity factors. It was intended to recruit 326 MDD patients for the assessment, assuming a 30% dropout rate. Regretfully, the novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak hindered subject enrollment, and only 281 depressed individuals were eventually enrolled. Ultimately, 206 people were enrolled in the baseline study, and 119 participants were included in the follow-up analysis. A two-tailed test with a test level 0.05 and an effect size of 0.3 (medium) was used for post hoc analysis in G*Power 3.1. This investigation's test power (1-β) was determined to be 0.99.

The independent-sample t-test for quantitative variables or the χ2 test for qualitative variables was used to analyze differences in demographic or clinical characteristics in the overall MDD group and the follow-up subgroup, patients with and without follow-up data, and patients with and without clinical remission as appropriate.

A multistep procedure was utilized to investigate the cumulative effects of stress-sensitivity factors[26]. The initial step involved identifying participants with high levels of stress-sensitivity factors, defined as those falling within the highest quartile of the research cohort on each scale (Neuroticism, T-AI, S-AI, and PSS). Subsequently, the association between each stress-sensitivity factor and one or more manifestations of MDD in the hypothesized direction was examined using independent-sample t-tests. The false discovery rate was controlled to account for multiple comparisons, with a sig

A total of 206 patients with MDD were included in the analyses, and 119 (57.77%) completed the assessment at the end of the 8-week follow-up period. As shown in Table 1, no significant differences were observed in demographics and treatment regimens between the overall MDD group at baseline and the follow-up subgroup. Demographic and clinical information between patients with and without follow-up data also had no difference mostly (Supplementary Table 1). Most of the participants were females (71.8%) and unmarried (75.7%). After 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment, the participants demonstrated significant improvement in the total score of HAMD-17, HAMA, BSSI, SDS, and PDQ-5 (all P < 0.01).

| Items | Overall MDD group (n = 206) | Subgroup based on follow-up data | Sig. |

| Age (years) | 23 (10) | 22 (9) | 0.132 |

| Years of education | 14.52 ± 2.55 | 14.33 ± 2.66 | 0.530 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.02 ± 4.34 | 22.43 ± 4.78 | 0.424 |

| Gender (female), No. (%) | 148 (71.8) | 87 (73.1) | 0.806 |

| Marriage (unmarried), No. (%) | 156 (75.7) | 94 (79.0) | 0.713 |

| Ethnicity (Han), No. (%) | 187 (90.8) | 109 (91.6) | 0.803 |

| History of drinking, No. (%) | 39 (18.9) | 22 (18.5) | 0.983 |

| History of smoking, No. (%) | 31 (15.0) | 17 (14.3) | 0.947 |

| Depressive episodes | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.493 |

| HAMD-17 score at baseline | 21.24 ± 5.28 | 21.94 ± 5.05 | 0.557 |

| HAMD-17 score at the end of follow-up1 | NA | 10.88 ± 7.12 | < 0.001a |

| HAMA score at baseline | 21.38 ± 7.54 | 21.51 ± 7.58 | 0.883 |

| HAMA score at the end of follow-up1 | NA | 11.69 ± 7.74 | < 0.001a |

| BSSI score at baseline | 8.07 ± 7.68 | 7.57 ± 7.52 | 0.568 |

| BSSI score at the end of follow-up1 (n = 66) | NA | 5.67 ± 7.10 | 0.004a |

| SDS score at baseline | 18.50 ± 5.96 | 19.01 ± 6.07 | 0.466 |

| SDS score at the end of follow-up1 | NA | 11.91 ± 7.57 | < 0.001a |

| PDQ-5 score at baseline | 11.88 ± 3.54 | 11.69 ± 3.46 | 0.630 |

| PDQ-5 score at the end of follow-up1 | NA | 8.27 ± 4.58 | < 0.001a |

| Antidepressants at baseline | |||

| SSRIs, No. (%) | 66 (32) | 43 (36.1) | 0.451 |

| SNRIs, No. (%) | 20 (9.7) | 12 (10.1) | 0.913 |

| SARIs, No. (%) | 98 (47.6) | 62 (52.1) | 0.432 |

| Others2, No. (%) | 14 (6.8) | 7 (5.9) | 0.747 |

| Antidepressants at the end of follow-up | |||

| SSRIs, No. (%) | NA | 67 (32.5) | NA |

| SNRIs, No. (%) | NA | 18 (8.7) | NA |

| SARIs, No. (%) | NA | 86 (41.7) | NA |

| Others2, No. (%) | NA | 21 (17.6) | NA |

| Neuroticism score at baseline | 44.92 ± 5.97 | 45.05 ± 5.70 | 0.919 |

| T-AI score at baseline | 59.98 ± 7.06 | 60.15 ± 6.80 | 0.824 |

| PSS score at baseline | 24.76 ± 4.96 | 24.83 ± 5.28 | 0.899 |

| S-AI score at baseline | 56.64 ± 8.67 | 56.47 ± 8.06 | 0.858 |

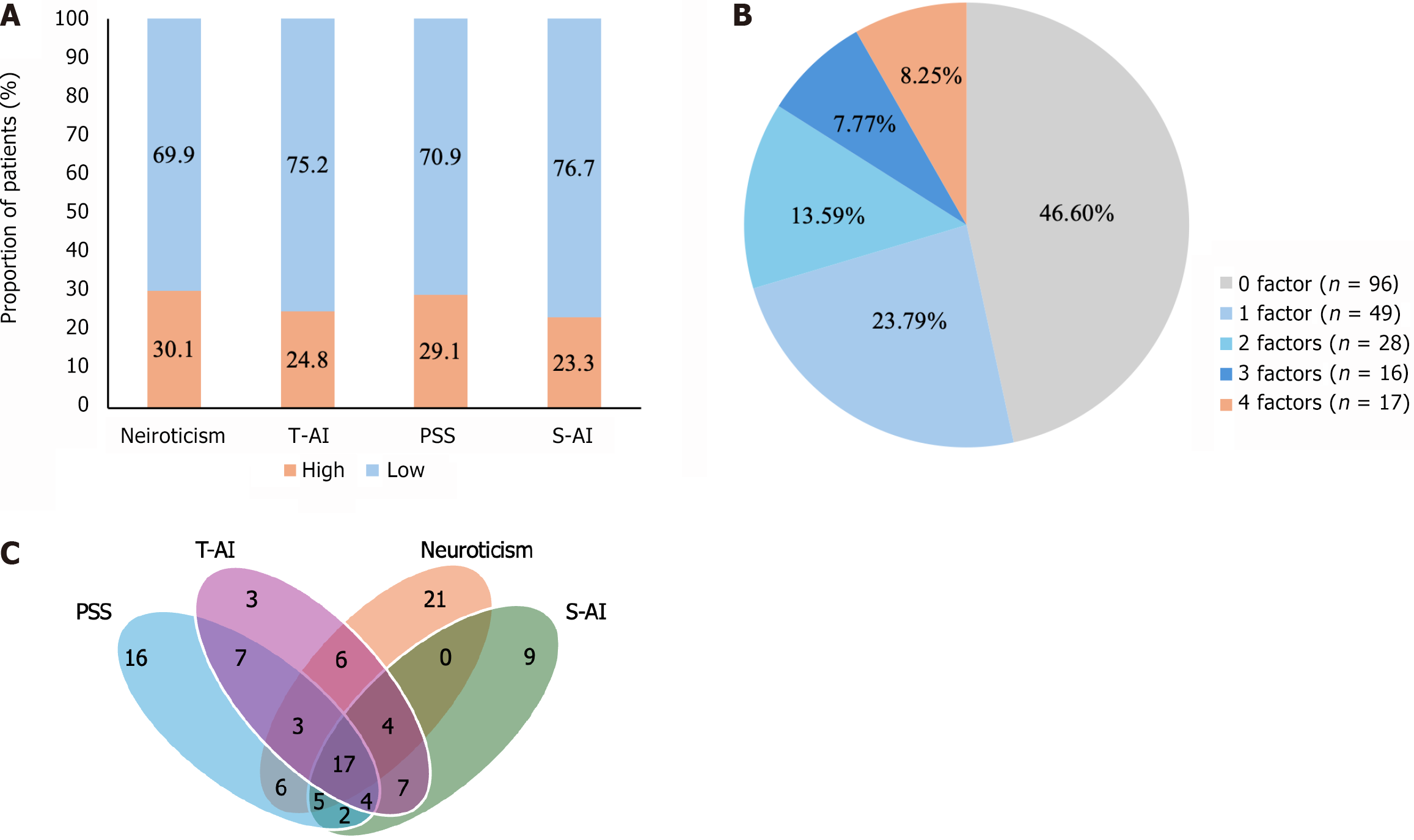

The prevalence of high-level stress-sensitivity factors is illustrated in Figure 1A. Among the 206 patients with MDD, 110 (53.40%) presented with at least one high-level stress-sensitivity factor, 29.61% exhibited two or more high-level factors, and 8.25% had all four high-level factors (Figure 1B).

The overlap of high-level stress-sensitivity factors is illustrated in Figure 1C. Thirty patients exhibited both high-level neuroticism and trait anxiety, while twenty-eight displayed both high-level perceived stress and state anxiety. The proportion of overlapping within-category factors (neuroticism and trait anxiety, or perceived stress and state anxiety) was not significantly different from the proportion of overlapping between-category factors (neuroticism and state anxiety, neuroticism and perceived stress, trait anxiety and perceived stress, or trait anxiety and state anxiety) (all P > 0.05). Ninety-six patients (46.6%) exhibited no high-level stress-sensitivity factors and were not included in the diagram. The size of different areas was not exactly proportional to the number of patients in the corresponding area.

As presented in Supplementary Table 2 in the appendix, patients who did not achieve clinical remission at the end of the 8-week follow-up (HAMD-17 total score ≥ 8) exhibited a significantly higher proportion of baseline high-level trait-related factors (i.e., the proportion of patients with both high-level Neuroticism and T-AI) compared to those who achieved remission through follow-up (P = 0.023).

As shown in Table 2, in the overall MDD group at baseline, significant associations with at least four clinical manifestations were observed for all four factors. For instance, patients with a high T-AI score at baseline exhibited significantly higher HAMD-17, HAMA, BSSI, SDS, and PDQ-5 scores than those with a low T-AI score (all P < 0.01). However, only two trait-related factors, i.e., neuroticism and trait anxiety, survived the false discovery rate correction at the end of the 8-week follow-up (all P < 0.05).

| Items | Groups | HAMD-17 at baseline | HAMD-17 at the end of follow-up | HAMA at baseline | HAMA at the end of follow-up | BSSI at baseline | BSSI at the end of follow-up | SDS at baseline | SDS at the end of follow-up | PDQ-5 at baseline | PDQ-5 at the end of follow-up |

| Neuroticism | Low-level | 20.88 ± 5.42 | 9.54 ± 6.56 | 20.75 ± 7.65 | 10.31 ± 7.31 | 6.92 ± 7.04 | 4.23 ± 5.77 | 17.28 ± 6.01 | 10.90 ± 7.34 | 11.35 ± 3.47 | 7.34 ± 4.20 |

| High-level | 22.10 ± 4.86 | 14.11 ± 7.46 | 22.83 ± 7.12 | 14.97 ± 7.87 | 10.74 ± 8.46 | 8.55 ± 8.64 | 21.35 ± 4.74 | 14.31 ± 7.68 | 13.11 ± 3.40 | 10.49 ± 4.75 | |

| Sig. | 0.070 | 0.002a | 0.024a | 0.003a | 0.003a | 0.044a | < 0.001a | 0.035a | 0.001a | 0.001a | |

| Trait anxiety | Low-level | 20.08 ± 5.05 | 9.17 ± 6.38 | 20.00 ± 6.94 | 9.95 ± 6.46 | 6.44 ± 6.21 | 4.19 ± 5.13 | 17.52 ± 6.18 | 10.79 ± 7.12 | 11.51 ± 3.61 | 7.38 ± 4.17 |

| High-level | 24.76 ± 4.33 | 15.97 ± 6.88 | 25.55 ± 7.84 | 16.83 ± 8.98 | 13.04 ± 9.46 | 9.61 ± 9.86 | 21.49 ± 3.97 | 15.23 ± 7.99 | 13.02 ± 3.06 | 10.91 ± 4.79 | |

| Sig. | < 0.001a | < 0.001a | < 0.001a | < 0.001a | < 0.001a | 0.038a | < 0.001a | 0.005a | 0.008a | < 0.001a | |

| Perceived stress | Low-level | 20.08 ± 5.13 | 10.26 ± 7.05 | 20.00 ± 7.01 | 10.67 ± 7.45 | 6.76 ± 7.15 | 4.84 ± 5.80 | 17.48 ± 5.97 | 11.28 ± 7.35 | 11.36 ± 3.50 | 7.78 ± 4.59 |

| High-level | 24.07 ± 4.54 | 12.44 ± 7.17 | 24.72 ± 7.80 | 14.23 ± 7.99 | 11.27 ± 8.04 | 7.32 ± 9.09 | 21.00 ± 5.16 | 13.47 ± 8.00 | 13.15 ± 3.31 | 9.50 ± 4.40 | |

| Sig. | < 0.001a | 0.132 | < 0.001a | 0.023 | < 0.001a | 0.253 | < 0.001a | 0.155 | 0.001a | 0.063 | |

| State anxiety | Low-level | 20.41 ± 5.13 | 10.23 ± 6.91 | 20.33 ± 7.44 | 10.59 ± 6.93 | 6.82 ± 6.89 | 5.20 ± 6.08 | 17.59 ± 6.04 | 11.38 ± 7.39 | 11.52 ± 3.59 | 7.80 ± 4.48 |

| High-level | 23.98 ± 4.87 | 13.11 ± 7.50 | 24.81 ± 6.89 | 15.42 ± 9.23 | 12.19 ± 8.71 | 6.75 ± 9.11 | 21.50 ± 4.58 | 13.70 ± 8.04 | 13.08 ± 3.09 | 9.87 ± 4.66 | |

| Sig. | < 0.001a | 0.064 | < 0.001a | 0.017 | < 0.001a | 0.418 | < 0.001a | 0.162 | 0.007a | 0.038 |

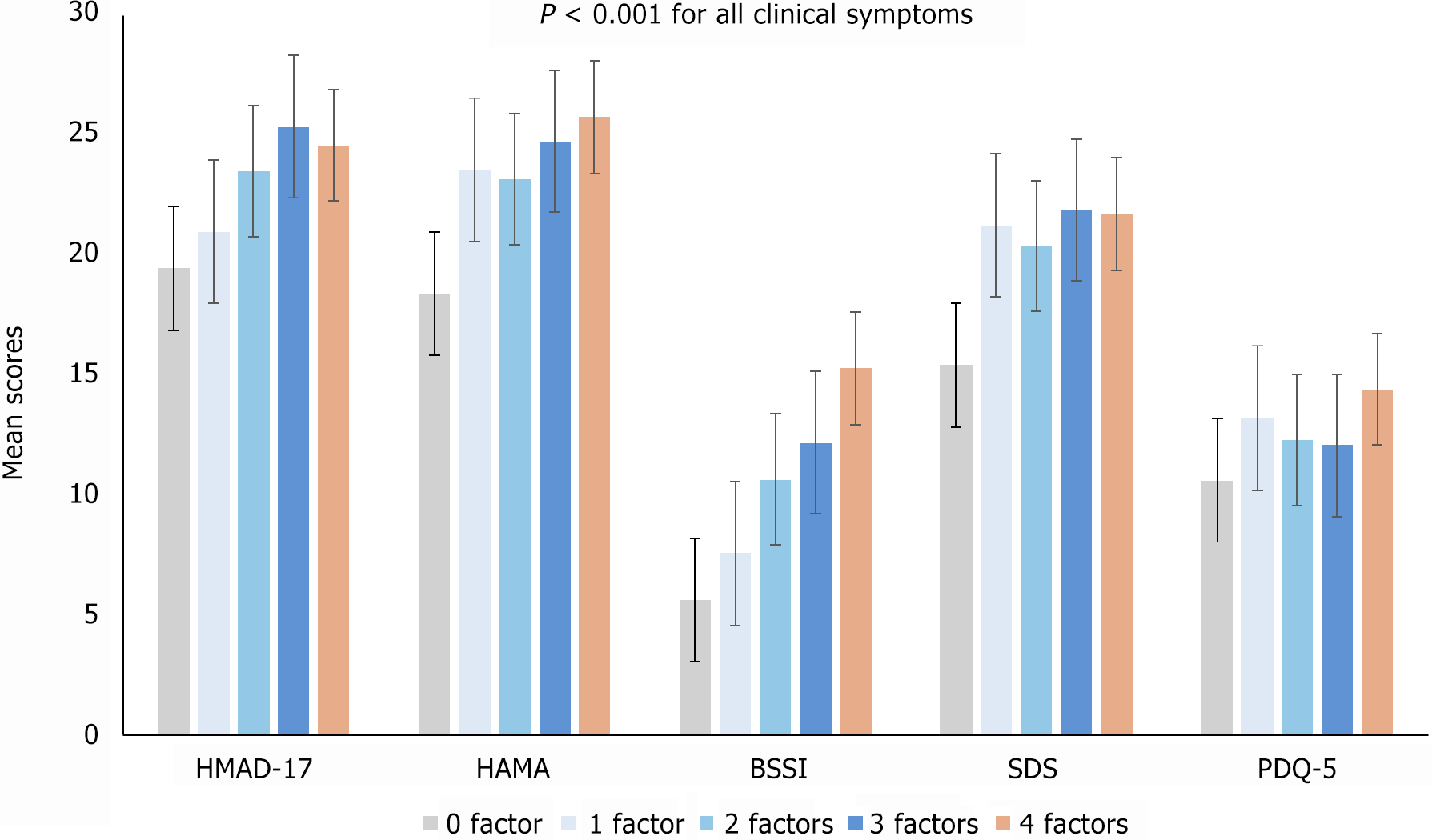

The results of the one-way analysis of variance with linear trend analysis are presented in Table 3 and Figure 2. At baseline, the cumulative effects of all four high-level stress-sensitivity factors on the total scores of HAMD-17, HAMA, BSSI, SDS, and PDQ-5 were significant in the overall MDD group (all P < 0.001). There was a gradual increase in the severity of clinical manifestations at baseline with the increase in the number of high-level stress-sensitivity factors (Figure 2).

| Items | Time | All factors Partial eta-squared (η2) | Sig. | PSS + S-AI Partial eta-squared (η2) | Sig. | Neuroticism + T-AI partial eta-squared (η2) | Sig. |

| HAMD-17 | Baseline | 0.158 | < 0.001a | 0.153 | < 0.001a | 0.085 | < 0.001a |

| At the end of follow-up | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.204 | < 0.001a | |

| HAMA | Baseline | 0.145 | < 0.001a | 0.129 | < 0.001a | 0.072 | < 0.001a |

| At the end of follow-up | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.155 | < 0.001a | |

| BSSI | Baseline | 0.160 | < 0.001a | 0.117 | < 0.001a | 0.135 | < 0.001a |

| At the end of follow-up (n = 66) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.156 | 0.002a | |

| SDS | Baseline | 0.240 | < 0.001a | 0.132 | < 0.001a | 0.145 | < 0.001a |

| At the end of follow-up | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.072 | 0.003a | |

| PDQ-5 | Baseline | 0.138 | < 0.001a | 0.065 | < 0.001a | 0.066 | < 0.001a |

| At the end of follow-up | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.143 | < 0.001a |

The contribution of trait-related and state-related factors on MDD symptoms and follow-up outcomes was investigated in subsequent analyses (Table 3). Cumulative effects of state-related factors (perceived stress and state anxiety) and trait-related factors (neuroticism and trait anxiety) were separately significant on the total scores of HAMD-17, HAMA, BSSI, SDS, and PDQ-5 at baseline (all P < 0.001). At the end of the 8-week follow-up, a significant cumulative effect of trait-related factors (neuroticism and trait anxiety) only on clinical outcomes was found (all P < 0.01).

Furthermore, the cumulative effect sizes of state-related factors on the baseline score of HAMD-17 were most significant among the baseline manifestations of MDD (Table 3, partial η2 = 0.153, P < 0.001), larger than that of trait-related factors on HAMD-17 (partial η2state = 0.153, partial η2trait = 0.085). Multivariable regression analysis showed that among the state-related factors, only the score of PSS had a significant predictive effect on the score of HAMD-17 at baseline (Table 4, standardized β = 0.195, P < 0.05). At the end of the follow-up, the cumulative effect sizes of trait-related factors on the score of HAMD-17 and BSSI were the most significant (partial η2 = 0.204 and 0.156; both P < 0.01). Further analysis of multivariable regression showed that at the end of the follow-up, the score of T-AI could predict the score of HAMD-17 (Table 4, standardized β = 0.247, P < 0.05), and the score of neuroticisms could predict the score of BSSI (standardized β = 0.392, P < 0.05).

The present study explored the cumulative effects of high-level stress-sensitivity factors on the clinical symptoms and follow-up outcomes in patients with MDD. The results showed that: (1) At baseline, more than half of the MDD patients had at least one high-level stress-sensitivity factor, and almost a third displayed high levels in two or more stress-sensitivity factors; (2) Compared with patients with clinical remission at the end of the 8-week follow-up, those without clinical remission showed higher proportional high-level trait-related factors; (3) At baseline, MDD patients with more high-level stress-sensitivity factors showed more severe clinical manifestations. The severity of depressive symptoms was more likely to be attributed to high-level state-related factors compared to trait-related factors. Only perceived stress could predict the severity of depressive symptoms among the two state-related factors; and (4) MDD patients with more high-level trait-related factors showed poorer outcomes at the end of follow-up, especially in the severity of depressive symptoms, which could be predicted by trait anxiety, and suicide risk which could be predicted by neuroticism.

The results supported the first hypothesis that MDD patients with more high-level stress-sensitivity factors had more severe clinical manifestations at baseline. This complements the findings of previous studies exploring the relationship between stress-sensitivity factors and depression[36]. Furthermore, the findings that state-related factors had a more significant effect on depressive symptoms during an MDD episode compared to trait-related factors also partially supported our third hypothesis.

Additionally, the results indicated that perceived stress could predict the severity of depressive symptoms at baseline, which was aligned with the prior scholarly work. According to Cristóbal-Narváez et al[37], there was a linear increase in the prevalence of depression with increasing perceived stress scores; specifically, a one-unit increase in the perceived stress score was associated with 1.40 times higher odds for depression (95%CI: 1.35-1.44). However, it cannot be ignored that there might be a potential overlap between perceived stress and depression. To investigate the impact of perceived stress on the severity of depression prospectively by minimizing any overlapping effects, future research may look at examining perceived stress before depression. This could serve as a guide to lessen the intensity of depressed symptoms during acute episodes.

Meanwhile, this study indicated that MDD patients with more high-level trait-related factors were more likely to have poorer follow-up outcomes, especially in depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation, which partially supported our second and third hypotheses. Although previous studies have reported that MDD patients with high neuroticism and trait anxiety tend to have poorer clinical outcomes[20,38], our study importantly demonstrated that multiple trait-related factors cumulatively influenced follow-up outcomes. More attention should be given to trait-related factors to advance the development of interventions targeting these factors to improve the prognosis for long-term treatment.

Furthermore, suicide risk has been previously found to be influenced by both trait and state components, such as trait/state hopelessness and trait/state anxiety[21], which was inconsistent with the present study finding that only neuroticism can predict suicide risk. Meanwhile, the limited inclusion of trait or state factors in this paper may have limited the discovery of more positive results. For instance, prior research has indicated that stressful life events may influence the risk of suicide[39], a finding that should be further explored in future studies as it was not examined in this study at baseline or during follow-up.

According to the MDD stress sensitization hypothesis, patients gradually become more sensitive to stress, which lowers the degree of stress triggering episode onset with each subsequent episode[40]. Even though we found that bad outcomes of MDD were linked to high levels of trait-related characteristics, it is still crucial to look into more detailed mechanisms and better understand how these temperamental predictors affect outcomes. Previous research has found several intriguing explanations, including genetic and heritable variables, aberrant brain structure and function, neuroimmune and endocrine system dysfunction, inappropriate emotion regulation, dysfunctional cognition, and socio-environmental stresses[41-44]. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is a significant stress response system, and excessive responses may have an impact on depression symptoms and suicide[45].

Adapting to adversity is the process of resilience, which necessitates the integration of several core and peripheral systems[46]. Previous research suggests that patients with depression may exhibit a more favorable response to treatment when characterized by low levels of trait anxiety, high resilience, or a combination of these factors[20]. A more thorough understanding of MDD's susceptibility may be possible with research integrating stress sensitivity and resilience mechanisms and how they interact with MDD. This is an important area for future study.

The idea that psychological therapies can address temperamental vulnerability has received some preliminary support from researchers who have worked to develop psychotherapy for neurotic and trait anxiety temperaments. Barlow et al[47] devised a comprehensive cognitive-behavioral intervention strategy for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders. Numerous randomized controlled trials confirmed that patients with emotional disorders who received treatment using a unified protocol saw reductions in neuroticism, which was linked to improvements in core symptoms, functional impairment, and emotional disorder quality of life[48,49].

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors[50], lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted therapy[51,52], medications with anti-inflammatory effects targeted to microglia[53], virtual reality-based biofeedback[54], lavender inhalation[55], and music therapy[56] have all been found to potentially lower neuroticism and state-trait anxiety. More high-quality RCTs with more uniform study designs are required to validate these results.

In summary, the above findings underscored the screening and assessment of stress-sensitivity factors and the need for comprehensive investigations into the mechanism underlying the relationship between stress sensitivity and MDD. The findings also highlighted the importance of trait-related stress-sensitivity factors in the follow-up outcomes, with implications for advancing the development of interventions targeting these factors to achieve clinical remission and better outcomes.

Firstly, while our study incorporated longitudinal data, its design did not examine causal relationships between stress-sensitivity factors and MDD follow-up outcomes, a capability better suited to interventional studies. Secondly, the evaluation of stress-sensitivity components relied on self-reported scales. Future research should integrate multi-dimensional objective indicators, such as neuroimaging markers, endocrine hormones, inflammatory factors, and susceptibility genes to gain a more comprehensive understanding of stress sensitivity phenotypes. Thirdly, the sample predominantly consisted of young, single Chinese women. Therefore, the findings require validation in more diverse populations and may not be generalizable to other demographic groups. Fourthly, some conceptual overlap may exist between depression and state-related stress-sensitivity characteristics. Future studies should refine their designs to minimize the potential interference of such overlaps on the results. Fifthly, the study focused on trait-related characteristics, including stress-sensitive traits like neuroticism and trait anxiety. However, the relatively short 8-week follow-up period limits a deeper understanding of how stress-sensitivity parameters may influence longer-term outcomes of MDD, such as relapse or chronic dysfunction. Further research with extended and more comprehensive follow-up periods is needed. Finally, 42.23% of participants were lost to follow-up during the 8-week period, which could have affected the findings. The clinical outcomes of patients who completed follow-up may differ from those who were lost to follow-up. Enhancing follow-up methodologies and efforts to increase follow-up rates are essential to improving the accuracy and generalizability of future studies.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the cumulative effect of stress-sensitivity factors on MDD manifestations and follow-up outcomes. The varying associations between stress-sensitivity factors and different clinical manifestations highlighted the need for screening and assessment of stress-sensitivity factors in psychiatric clinical practice and call for multi-faceted and holistic approaches. Particularly, attention to trait-related factors is essential for improving follow-up outcomes and reducing the risk of suicide in MDD. Understanding the function of stress sensitivity in depression can be advanced by incorporating future research on stress-related psychological and neurobiological pathways.

We would like to express our gratitude to all participants in the study.

| 1. | Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, Yu Y, Kou C, Xu X, Lu J, Wang Z, He S, Xu Y, He Y, Li T, Guo W, Tian H, Xu G, Xu X, Ma Y, Wang L, Wang L, Yan Y, Wang B, Xiao S, Zhou L, Li L, Tan L, Zhang T, Ma C, Li Q, Ding H, Geng H, Jia F, Shi J, Wang S, Zhang N, Du X, Du X, Wu Y. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:211-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1590] [Cited by in RCA: 1358] [Article Influence: 226.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cai H, Jin Y, Liu S, Zhang Q, Zhang L, Cheung T, Balbuena L, Xiang YT. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and planning in patients with major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of observation studies. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:148-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Knight MJ, Baune BT. Cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31:26-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang S, Leri F, Rizvi SJ. Anhedonia as a central factor in depression: Neural mechanisms revealed from preclinical to clinical evidence. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;110:110289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mielacher C, Scheele D, Kiebs M, Schmitt L, Dellert T, Philipsen A, Lamm C, Hurlemann R. Altered reward network responses to social touch in major depression. Psychol Med. 2024;54:308-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gili M, García Toro M, Armengol S, García-Campayo J, Castro A, Roca M. Functional impairment in patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid anxiety disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:679-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:293-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1582] [Cited by in RCA: 1760] [Article Influence: 88.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Stress-processes and depressive symptomatology. J Abnorm Psychol. 1986;95:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vinkers CH, Joëls M, Milaneschi Y, Kahn RS, Penninx BW, Boks MP. Stress exposure across the life span cumulatively increases depression risk and is moderated by neuroticism. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31:737-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kraus C, Kadriu B, Lanzenberger R, Zarate CA Jr, Kasper S. Prognosis and improved outcomes in major depression: a review. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bale TL. Stress sensitivity and the development of affective disorders. Horm Behav. 2006;50:529-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wichers M, Geschwind N, Jacobs N, Kenis G, Peeters F, Derom C, Thiery E, Delespaul P, van Os J. Transition from stress sensitivity to a depressive state: longitudinal twin study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:498-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hammen C. Stress sensitivity in psychopathology: mechanisms and consequences. J Abnorm Psychol. 2015;124:152-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | van Winkel M, Nicolson NA, Wichers M, Viechtbauer W, Myin-Germeys I, Peeters F. Daily life stress reactivity in remitted versus non-remitted depressed individuals. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30:441-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Myin-Germeys I, Peeters F, Havermans R, Nicolson NA, DeVries MW, Delespaul P, Van Os J. Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis and affective disorder: an experience sampling study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Harkness KL, Hayden EP, Lopez-Duran NL. Stress sensitivity and stress sensitization in psychopathology: an introduction to the special section. J Abnorm Psychol. 2015;124:1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Drake KE, Gudjonsson GH, Sigfusdottir ID, Sigurdsson JF. An investigation into the relationship between the reported experience of negative life events, trait stress-sensitivity and false confessions among further education students in Iceland. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;81:135-140. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:885-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1770] [Cited by in RCA: 1722] [Article Influence: 114.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang T, Li M, Xu S, Liu B, Wu T, Lu F, Xie J, Peng L, Wang J. Relations between trait anxiety and depression: A mediated moderation model. J Affect Disord. 2019;244:217-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Min JA, Lee NB, Lee CU, Lee C, Chae JH. Low trait anxiety, high resilience, and their interaction as possible predictors for treatment response in patients with depression. J Affect Disord. 2012;137:61-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Burr EM, Rahm-Knigge RL, Conner BT. The Differentiating Role of State and Trait Hopelessness in Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempt. Arch Suicide Res. 2018;22:510-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bolger N, Zuckerman A. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:890-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Corr R, Pelletier-Baldelli A, Glier S, Bizzell J, Campbell A, Belger A. Neural mechanisms of acute stress and trait anxiety in adolescents. Neuroimage Clin. 2021;29:102543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li H, Li W, Wei D, Chen Q, Jackson T, Zhang Q, Qiu J. Examining brain structures associated with perceived stress in a large sample of young adults via voxel-based morphometry. Neuroimage. 2014;92:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Merz CJ, Wolf OT. Examination of cortisol and state anxiety at an academic setting with and without oral presentation. Stress. 2015;18:138-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Simrén M, Törnblom H, Palsson OS, Van Oudenhove L, Whitehead WE, Tack J. Cumulative Effects of Psychologic Distress, Visceral Hypersensitivity, and Abnormal Transit on Patient-reported Outcomes in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:391-402.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sun J, Gao N, Wu Q, Li Y, Zhang L, Jiang Z, Wang Z, Liu J. High plasma nesfatin-1 level in Chinese adolescents with depression. Sci Rep. 2023;13:15288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | HAMILTON M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21041] [Cited by in RCA: 22852] [Article Influence: 351.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | HAMILTON M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6169] [Cited by in RCA: 6775] [Article Influence: 102.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Beck AT, Steer RA, Ranieri WF. Scale for Suicide Ideation: psychometric properties of a self-report version. J Clin Psychol. 1988;44:499-505. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Hodgins DC. Reliability and validity of the Sheehan Disability Scale modified for pathological gambling. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16831] [Cited by in RCA: 17393] [Article Influence: 414.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Rosellini AJ, Brown TA. The NEO Five-Factor Inventory: latent structure and relationships with dimensions of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large clinical sample. Assessment. 2011;18:27-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Spielberger CD, Gonzales-Reigosa F, Martinez-Urrutia A, Natalicio LFS, Natalicio DS. Development of the Spanish edition of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Revista Interamericana de Psicología. 1971;5:145-158. |

| 35. | Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Routledge. 1988. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 36. | Vinograd M, Williams A, Sun M, Bobova L, Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Vrshek-Schallhorn S, Mineka S, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG. Neuroticism and interpretive bias as risk factors for anxiety and depression. Clin Psychol Sci. 2020;8:641-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Cristóbal-Narváez P, Haro JM, Koyanagi A. Perceived stress and depression in 45 low- and middle-income countries. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:799-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Quilty LC, De Fruyt F, Rolland JP, Kennedy SH, Rouillon PF, Bagby RM. Dimensional personality traits and treatment outcome in patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:241-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Macrynikola N, Miranda R, Soffer A. Social connectedness, stressful life events, and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors among young adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;80:140-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Stroud CB, Harkness K, Hayden E. The stress sensitization model. In: Harkness KL, Hayden EP, editors. The Oxford handbook of stress and mental health. 2020: 349-370. |

| 41. | Herzog S, Bartlett EA, Zanderigo F, Galfalvy HC, Burke A, Mintz A, Schmidt M, Hauser E, Huang YY, Melhem N, Sublette ME, Miller JM, Mann JJ. Neuroinflammation, Stress-Related Suicidal Ideation, and Negative Mood in Depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kalin NH. Stress, Heritability, and Genetic Factors Influencing Depression, PTSD, and Suicidal Behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:699-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Wiebenga JXM, Heering HD, Eikelenboom M, van Hemert AM, van Oppen P, Penninx BWJH. Associations of three major physiological stress systems with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in patients with a depressive and/or anxiety disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;102:195-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Belleau EL, Treadway MT, Pizzagalli DA. The Impact of Stress and Major Depressive Disorder on Hippocampal and Medial Prefrontal Cortex Morphology. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85:443-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 58.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Underwood MD, Galfalvy H, Hsiung SC, Liu Y, Simpson NR, Bakalian MJ, Rosoklija GB, Dwork AJ, Arango V, Mann JJ. A Stress Protein-Based Suicide Prediction Score and Relationship to Reported Early-Life Adversity and Recent Life Stress. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023;26:501-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Cathomas F, Murrough JW, Nestler EJ, Han MH, Russo SJ. Neurobiology of Resilience: Interface Between Mind and Body. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;86:410-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Barlow DH, Sauer-zavala S, Carl JR, Bullis JR, Ellard KK. The Nature, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Neuroticism. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2:344-365. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 48. | Carlucci L, Saggino A, Balsamo M. On the efficacy of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;87:101999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 49. | Stumpp NE, Southward MW, Sauer-Zavala S. Assessing Theories of State and Trait Change in Neuroticism and Symptom Improvement in the Unified Protocol. Behav Ther. 2024;55:93-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Quilty LC, Meusel LA, Bagby RM. Neuroticism as a mediator of treatment response to SSRIs in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;111:67-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Holze F, Gasser P, Müller F, Strebel M, Liechti ME. LSD-assisted therapy in patients with anxiety: open-label prospective 12-month follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 2024;225:362-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Holze F, Gasser P, Müller F, Dolder PC, Liechti ME. Lysergic Acid Diethylamide-Assisted Therapy in Patients With Anxiety With and Without a Life-Threatening Illness: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase II Study. Biol Psychiatry. 2023;93:215-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 72.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Rooney S, Sah A, Unger MS, Kharitonova M, Sartori SB, Schwarzer C, Aigner L, Kettenmann H, Wolf SA, Singewald N. Neuroinflammatory alterations in trait anxiety: modulatory effects of minocycline. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Cho Y, Kim H, Seong S, Park K, Choi J, Kim MJ, Kim D, Jeon HJ. Effect of virtual reality-based biofeedback for depressive and anxiety symptoms: Randomized controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2024;361:392-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Donelli D, Antonelli M, Bellinazzi C, Gensini GF, Firenzuoli F. Effects of lavender on anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine. 2019;65:153099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Garcia-Gonzalez J, Ventura-Miranda MI, Requena-Mullor M, Parron-Carreño T, Alarcon-Rodriguez R. State-trait anxiety levels during pregnancy and foetal parameters following intervention with music therapy. J Affect Disord. 2018;232:17-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |