Published online Feb 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i2.99252

Revised: December 1, 2024

Accepted: December 23, 2024

Published online: February 19, 2025

Processing time: 82 Days and 23.1 Hours

Cancer patients with an implanted venous access port (IVAP) often manage their care at home during chemotherapy intervals, including maintaining the device, monitoring complications, and following medication instructions. Home care ensures continued support after discharge. However, due to factors such as age, gender, culture, psychological status, and family support, the quality of home care varies significantly. Understanding these factors can help provide targeted guidance to improve the care of cancer patients.

To explore IVAP chemotherapy on home care quality and its association with mental health and family support for cancer patients.

This investigative study was based on a medical records system. It investigated the relationship between psychological status, family support, and home care quality in 180 patients with cancer undergoing IVAP chemotherapy. Psychological status was assessed using the State Anxiety Inventory (S-AI); family support was assessed using the Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS), and home care quality was evaluated using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30). Pearson’s correlation and Structural Equation Modeling were used to analyze the interplay between these factors.

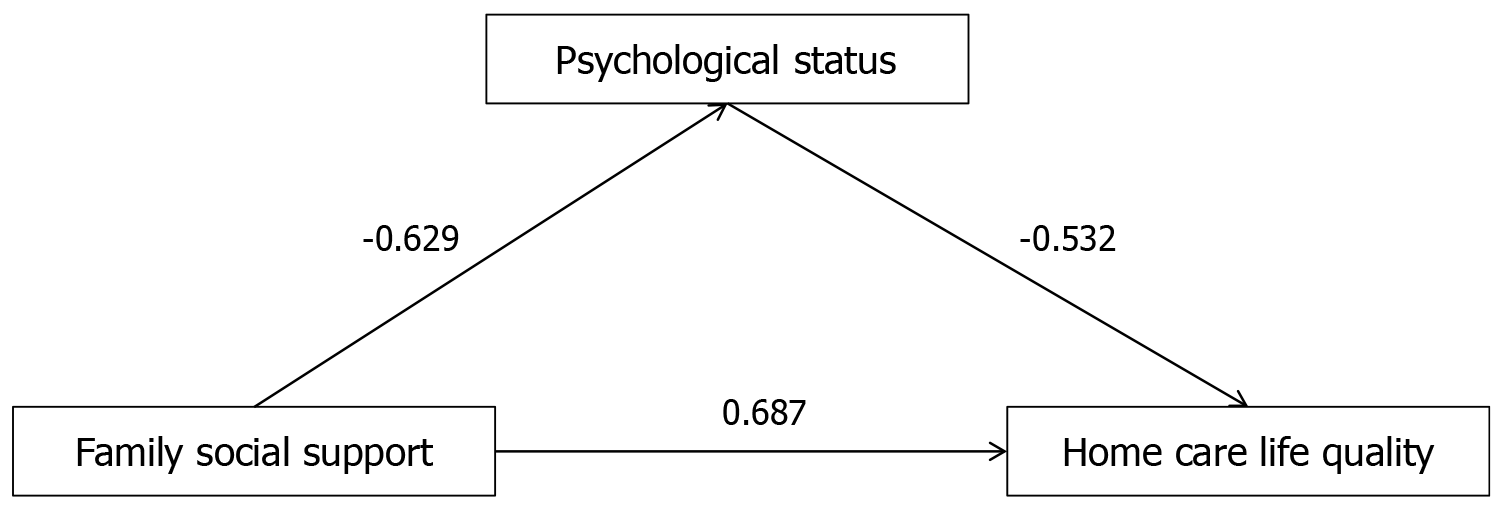

The average S-AI score was 47.52 ± 14.47, PSSS was 52.48 ± 12.64, and EORTC QLQ-C30 was 70.09 ± 17.32. A substantial inverse relationship was observed between the EORTC QLQ-C30 and S-AI scores (r = -0.712). A significant positive correlation was found between the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the PSSS, with a correlation coefficient of (r = 0.744). The multiple linear regression analysis indicated that family social support, psychological status, and average monthly family income were the main factors influencing the variation in the quality of home care, explaining 71.9% of the variation. The Structural Equation Modeling results indicated that psychological status acted as a partial mediator in the association between family social support and home care quality of life, explaining 32.78% of the mediation effect.

Psychological status and family social support positively impacted cancer patients’ home care quality, with psychology partially mediating this effect.

Core Tip: Psychological status and family social support play crucial roles in improving the quality of life of patients with cancer receiving home care. Specifically, family social support helps improve patients’ psychological status, reduces negative emotions such as anxiety and depression, and indirectly enhances their quality of life. Family social support has a significant positive impact on the quality of life of home-care cancer patients, and psychological status acts as a partial mediator of the association between family social support and quality of life.

- Citation: Jia HY, Yan LQ, Liu XB, Cao J. Correlation between psychological, family social support, and home nursing quality for an implanted venous access port. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(2): 99252

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i2/99252.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i2.99252

An implanted venous access port (IVAP) is an advanced subcutaneous venous access device composed of an injection base with a silicone diaphragm and a catheter system[1]. The IVAP can be punctured up to 2000 times, providing convenient and safe venous access for cancer patients undergoing multiple chemotherapy cycles. This approach significantly reduces the pain associated with frequent changes in infusion routes[2]. The literature indicates that the use of IVAPs in patients with breast cancer, colon cancer, lung cancer, and other tumors is increasing annually[1,3,4]. This trend reflects this technology’s growing recognition and acceptance among cancer patients.

During the indwelling period of the infusion port, cancer patients typically take the infusion port home for 2-3 weeks of recuperation between each chemotherapy interval. However, patients may encounter catheter-related complications during the home care period, such as mechanical phlebitis, local infection, partial catheter detachment, and catheter leakage[5,6]. Notably, the quality of life of patients receiving home care is directly linked to their therapeutic effect; however, this aspect is often overlooked in clinical practice.

In addition to physical health challenges, cancer patients frequently experience psychological distress throughout their treatment journey[7]. Family social support plays a crucial role in alleviating these pressures and enhancing patients’ overall quality of care[8]. Hence, exploring the relationship between the quality of life, psychological status, and family social support in cancer patients with IVAPs during home care is immensely important. Understanding these interconnections can lead to more effective guidance and recommendations for improving patient care. Additionally, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of cancer patients’ psychological well-being and family support, providing theoretical support for further improvements in home care for cancer patients.

For this investigative research study, we selected 180 cancer patients treated at the First Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University from April 2021 to March 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Diagnosed with a malignant tumor through clinical cytology or pathological examination; (2) Underwent intravenous (IV) chemotherapy or IVAP; (3) Aged ≥ 18 years; (4) Had good communication skills; and (5) Completed clinical data with analytical value.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Severe liver or kidney dysfunction and other major diseases; (2) History of allergy to chemotherapy drugs; (3) Cognitive impairment; (4) Participation in another clinical study; and (5) Pregnant or lactating. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University. All study participants or their legal guardians provided written informed consent before study enrollment.

According to the rough estimation method for the sample size proposed by Kendall[9], the sample size should be five to ten times the number of variables. In this study, there are a total of 29 variables. Considering a potential loss or invalidity of 10%-20% during the sample collection process, the sample size was determined to be at least 174 using the following formula: 29 × 5 × (1 + 20%) = 174. A total of 180 patients who met the sample size requirements were included in this study.

We reviewed the domestic and foreign literature and designed a general information questionnaire in line with the research objectives. The questionnaire mainly included: (1) General demographic data such as age, education, marital status, primary caregiver, and average monthly family income; and (2) Disease and port-related data such as tumor type, IVAP implantation site, and implantation time.

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory[10] is a widely used psychological assessment tool. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory consists of two subscales. The State Anxiety Inventory (S-AI) was also used in our study. The S-AI comprises 20 items, each with four options corresponding to 0-4 points. Scores vary from a minimum of 20 to a maximum of 80, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety.

The Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS)[11] consists of three dimensions (i.e., family support, friend support, and other support), encompassing 12 self-assessment items. Each self-assessment item was followed by seven options corresponding to 1-7 points. Scores vary from a minimum of 12 to a maximum of 84, with higher scores indicating greater support.

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30)[12] is a comprehensive tool that includes 30 items across 15 domains. It consists of five functional domains (i.e., physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social function) and three symptom domains (i.e., fatigue, pain, and nausea/vomiting). Additionally, it measures six single issues (i.e., dysphagia, appetite loss, sleep disorders, constipation, diarrhea, and financial problems) and includes one overall self-assessment question regarding the patient’s health status. Items 29 and 30 are scored from 1 to 7 points. Other items are scored from 1 to 4 points. We converted the raw scores for each item into standardized scores of 100. Higher scores in the functional domains indicate improved functionality. Conversely, higher scores in the symptom domains and individual items suggest more intense symptoms and a lower quality of life.

Topic selection phase: Many domestic and foreign studies were reviewed in the topic selection phase. Research topics were established based on the current medical situation in our country to ensure the study’s scientific, innovative, and practical nature. The questionnaires and scales used in this study have been extensively applied in previous research, and their validity and reliability have been well established, making them appropriate for this study.

Data compilation and analysis: To ensure the accuracy of data entry, two individuals independently ensured data. In cases where responses were missing or inconsistent, the corresponding questionnaire or scale was excluded from the analysis. In addition, expert guidance from a statistician was sought to verify the accuracy of data processing to ensure robust analytical methods.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 23.0. The scores of S-AI, PSSS, and EORTC QLQ-C30 were described using means and standard deviations (mean ± SDs), while the patients’ basic demographic data were described using frequencies and percentages [n (%)]. To analyze the impact of different demographic characteristics on the quality of life of cancer patients with IVAP receiving home care, we employed t-tests or analysis of variance. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to explore the relationships among psychological status, family social support, and quality of life in home care. Furthermore, multiple linear regression analysis was employed to investigate the factors influencing the quality of life in the home care of cancer patients with IVAPs. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to further analyze the interactive relationships among psychological status, family social support, and quality of life home care. The significance level for all statistical tests was set at α = 0.05.

In this study, the age range of the included patients was predominantly in the 45-59 years age group, accounting for 43.89% of the total. The educational levels of the patients were relatively evenly distributed. Regarding economic status, the average monthly household income was found to be low, with 62.78% of patients reporting a monthly household income of not more than 3000 yuan. Regarding marital status, most patients (60.56%) were married. In terms of home care, spouses were the primary caregivers for most patients, constituting 46.67% of the cases (Table 1).

| Items | Group | n (%) |

| Age (years) | 18-44 | 56 (31.11) |

| 45-59 | 79 (43.89) | |

| ≥ 60 | 45 (25.00) | |

| Sex | Female | 85 (47.22) |

| Male | 95 (52.78) | |

| Education | Junior high school and below | 62 (34.44) |

| High school (including technical secondary school) | 64 (35.56) | |

| University (including college) and above | 54 (30.00) | |

| Marital status | Married | 109 (60.56) |

| Single/divorced/widowed | 71 (39.44) | |

| Average monthly family income (yuan) | ≤ 3000 | 113 (62.78) |

| > 3000 | 67 (37.22) | |

| Primary caregiver | Spouse | 84 (46.67) |

| Children | 35 (19.44) | |

| Parent | 41 (22.78) | |

| Other | 20 (11.11) |

A total of 180 patients (39.44%) had breast cancer, followed by lung cancer (20.00%). Regarding the location of IVAP implantation, most (67.78 %) had the device implanted on the chest wall, and the majority of patients (46.11%) had their devices implanted for a period between 3 and 6 months. Most patients (92.78%) received health education (Table 2).

| Items | Group | n (%) |

| Tumor type | Breast cancer | 71 (39.44) |

| Lung cancer | 36 (20.00) | |

| Colorectal cancer | 22 (12.22) | |

| Ovarian cancer | 10 (5.56) | |

| Gastric cancer | 31 (17.22) | |

| Other | 10 (5.56) | |

| IVAP implantation site | Upper arm | 58 (32.22) |

| Chest wall | 122 (67.78) | |

| Implantation time (month) | < 3 | 65 (36.11) |

| 3-6 | 83 (46.11) | |

| > 6 | 32 (17.78) | |

| Whether to accept health education | Yes | 167 (92.78) |

| No | 13 (7.22) |

The S-AI scores of 180 patients with tumor at the port of implantable IV infusion were 47.52 ± 14.47, ranging from 25 to 77. The score of PSSS was 52.48 ± 12.64, ranging from 24 to 77, and the score of the family support dimension was the highest 19.05 ± 4.72. The overall health score of EORTC QLQ-C30 was 70.09 ± 17.32, ranging from 25 to 100 points (Table 3).

| Scale | Dimension | Scores |

| S-AI | 47.06 ± 13.85 | |

| PSSS | Family support | 19.05 ± 4.72 |

| Friends support | 17.24 ± 5.20 | |

| Other support | 16.19 ± 5.41 | |

| PSSS-total score | 52.48 ± 12.64 | |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | ||

| Functional domains | Physical function | 64.89 ± 18.65 |

| Role function | 56.11 ± 20.39 | |

| Cognitive function | 67.41 ± 22.13 | |

| Emotional function | 78.01 ± 16.07 | |

| Social function | 63.89 ± 21.25 | |

| Symptom domains | Fatigue | 19.69 ± 17.57 |

| Pain | 29.07 ± 14.43 | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 34.26 ± 20.30 | |

| Dysphagia | 31.85 ± 27.93 | |

| Loss of appetite | 31.11 ± 28.54 | |

| Sleep disorders | 38.89 ± 29.79 | |

| Constipation | 32.96 ± 24.41 | |

| Diarrhea | 31.30 ± 20.59 | |

| Financial difficulties | 53.70 ± 30.39 | |

| Overall health | 70.09 ± 17.32 |

The differences in the quality of life of cancer patients with IVAP in home care based on a cultural level and average monthly household income were statistically significant (P< 0.05) (Table 4).

| Items | Group | Overall health | Statistical value | P value |

| Age (years) | 18-44 | 70.59 ± 16.31 | 1.3611 | 0.259 |

| 45-59 | 67.94 ± 18.95 | |||

| ≥ 60 | 73.20 ± 15.36 | |||

| Sex | Female | 70.99 ± 16.06 | 0.6652 | 0.507 |

| Male | 69.26 ± 18.46 | |||

| Education | Junior high school and below | 61.00 ± 17.45 | 20.7621 | < 0.001 |

| High school (including technical secondary school) | 70.67 ± 15.66 | |||

| University (including college) and above | 79.80 ± 13.46 | |||

| Marital status | Married | 70.95 ± 18.22 | 0.8302 | 0.407 |

| Single/divorced/widowed | 68.75 ± 15.94 | |||

| Average monthly family income (yuan) | ≤ 3000 | 63.55 ± 16.39 | 7.5042 | < 0.001 |

| > 3000 | 81.09 ± 12.80 | |||

| Primary caregiver | Spouse | 69.33 ± 17.75 | 1.9331 | 0.126 |

| Children | 65.43 ± 15.64 | |||

| Parent | 74.59 ± 16.75 | |||

| Other | 72.10 ± 18.40 | |||

| Tumor type | Breast cancer | 71.37 ± 16.21 | 0.9961 | 0.422 |

| Lung cancer | 71.50 ± 14.87 | |||

| Colorectal cancer | 71.18 ± 18.68 | |||

| Ovarian cancer | 69.20 ± 17.03 | |||

| Gastric cancer | 63.94 ± 20.38 | |||

| Other | 73.30 ± 20.59 | |||

| IVAP implantation site | Upper arm | 68.55 ± 17.91 | 0.8132 | 0.417 |

| Chest wall | 70.80 ± 17.10 | |||

| Implantation time (month) | < 3 | 71.51 ± 18.94 | 0.4181 | 0.659 |

| 3-6 | 68.88 ± 16.84 | |||

| > 6 | 70.28 ± 15.43 | |||

| Whether to accept health education | Yes | 70.19 ± 17.58 | 0.3152 | 0.753 |

| No | 68.62 ± 14.48 |

Home care quality was negatively correlated with psychological status (r = -0.712), yet positively associated with family social support and scores on the three dimensions (r = 0.744, 0.594, 0.615, 0.628; P < 0.01) (Table 5).

The three variables included in the regression equation were average monthly family income, psychological status, and family social support. The larger the absolute value of the standardized regression coefficient, the greater the impact of the independent variable on the quality of life in home care. According to the research results, the order of effects on the quality of life in home care, from greatest to least, was family social support, psychological status, and average monthly family income. Among these, an R² = 0.719 indicated that the variables entering the equation collectively explained 71.9% of the variance in the patients’ quality of life in home care (Table 6).

| Items | β | SE | β’ | t | P value |

| Average monthly family income (yuan) | 6.402 | 1.889 | 0.179 | 3.389 | 0.001 |

| Psychological status | -0.477 | 0.062 | -0.381 | -7.661 | < 0.001 |

| Family social support | 0.610 | 0.069 | 0.444 | 8.817 | < 0.001 |

| Constant | 48.958 | 6.067 | - | 8.069 | < 0.001 |

Structural equation model analysis showed that psychological status acted as a partial mediator in the association between family social support and the quality of home care, explaining 32.78% of the mediating effect (Table 7 and Figure 1).

| Effects | Effect | Boot SE | t | P value | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Total effect | 1.022 | 0.069 | 14.875 | < 0.001 | 0.886 | 1.157 |

| Direct effect | 0.687 | 0.072 | 9.563 | < 0.001 | 0.545 | 0.829 |

| Indirect effect | 0.335 | 0.055 | - | - | 0.236 | 0.451 |

Chemotherapy for patients with malignant tumors usually requires four to six cycles. Owing to the long treatment duration and strong irritability of blood vessels caused by chemotherapy drugs, it is crucial to make rational choices regarding drugs and infusion methods during the treatment process. IVAPs have become a common choice for chemotherapy in cancer patients because of their convenience and safety[1]. However, with the increasing demand for home care, IVAP-related complications have attracted widespread attention[13]. Particularly during chemotherapy intervals, the risk of complications, such as catheter displacement, cannot be overlooked when patients perform self-care at home[5,6,13].

Currently, most studies have primarily focused on the application of IVAP during central venous catheterization and the potential complications associated with its use. However, there is a relative lack of in-depth analysis regarding the quality of home care and related management strategies for patients during chemotherapy intervals. Our results show that the quality of home care life for cancer patients with IVAPs ranks at 70.09 ± 17.32 points, indicating that the quality of home care life for cancer patients with IVAP is still low. However, this score is higher than the 58.9 ± 23.8 points reported by van Leeuwaarde et al[14] for patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors and the 53 ± 27 points reported by Davda et al[15] for cancer patients in Kenya. One possible explanation for the difference is the demographic composition of our study population: 75% of the patients were under the age of 60 years, with a smaller proportion of older patients. Younger patients generally have better physical conditions and learning abilities, which may enable them to carry out self-care and management more effectively. Another contributing factor may be the economic differences between the regions. As a lower-middle-income country, Kenya may have limited medical resources. In contrast, China’s higher level of economic development provides patients with more resources, such as access to higher-quality care products or the ability to hire professional caregivers. Additionally, van Leeuwaarde et al[14] pointed out that some patients expressed dissatisfaction with the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire. They found it challenging to understand the medical ter

Chemotherapy-induced physical discomfort, pain, and fear of disease can negatively affect the psychological status of patients. The psychological status of cancer patients, such as anxiety, depression, and other emotions, may affect their treatment compliance and care cooperation, thereby influencing their overall quality of life. Koch et al[16] surveyed the quality of life of patients with lung cancer using the Hornheide questionnaire and found that 39 patients (48.1%) required psychosocial support. Results from a least absolute shrinkage and selection operator analysis indicated that the median overall quality of life score for early-stage breast cancer patients at baseline was 69.9, which increased to 74.9 after one year, with the strongest factors being associated with social functioning, depression, fatigue, and emotional functioning[17]. Correlation analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between quality of life in home care and psychological status, aligning with the findings of Papadopoulou et al[18], who showed that most cancer patients experienced anxiety (83%), fear (75%), stress and sadness (51%), and depression (34%). These negative emotions can directly affect and ultimately lower a patient’s quality of life by reducing their motivation and ability to engage in daily activities and decreasing social interactions. Additionally, a lack of psychosocial support can exacerbate psychological distress and further diminish quality of life[19,20].

Our study found a significant positive correlation between the quality of home care quality and family social support, which aligns with the findings of Choi et al[21]. Social support can provide emotional comfort, information exchange, practical assistance, and empowerment-all of which contribute to improving the patient’s quality of life. Specifically, family social support may enhance an individual’s sense of self-efficacy, increasing their confidence in managing their health and daily activities[21]. It may include financial and practical assistance, such as helping with household chores or transportation, which alleviates stress and improves the overall quality of life of the patient.

We further analyzed the interrelationships among S-AI, PSSS, and EORTC QLQ-C30, using SEM. We found that psychological status acted as a partial mediator in the association between family social support and the quality of home care. In other words, family social support may help improve patients’ psychological health by reducing negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression, improving their quality of life. First, social support provides emotional comfort and practical assistance, alleviating the psychological stress and anxiety experienced by patients due to their illness[22]. Second, family support can enhance patients’ self-efficacy, increase their confidence in managing their disease, and help them adopt proactive self-care behaviors[21]. Additionally, increased social participation and a sense of social integration can provide patients with valuable information and resources to better cope with the challenges of the disease, further contributing to improved quality of life[16].

Based on these findings, the following suggestions and measures are proposed to improve the quality of home care for cancer patients: (1) Strengthening family social support: It is recommended that regular family support groups be organized to educate family members on how to provide effective emotional and practical support, as well as how to communicate with patients. These support groups, conducted both online and offline, can help enhance the caregiving abilities and psychological resilience of family members. By fostering a better understanding of caregiving roles and emotional support strategies, family members can more effectively assist patients, contributing to a higher quality of home care; (2) Improving patients’ psychological health: The S-AI reveals that cancer patients often experience high levels of anxiety. To address this issue, psychological counseling services should be provided, incorporating cognitive-behavioral therapy and stress management techniques to reduce anxiety and improve emotional well-being. Targeted psychological support can help patients manage the mental and emotional challenges of living with cancer, leading to improved quality of life and better health outcomes; (3) Providing financial support: The study’s multiple linear regression analysis showed that families’ monthly per capita income significantly influences home care quality variations. Financial assistance should be provided to economically disadvantaged families to mitigate financial barriers. Additionally, guiding families on how to access funding from governmental or non-governmental organizations can help alleviate the financial burden of home care, ensuring that patients receive the necessary support and services; and (4) Optimizing home care services: Community-based interventions have been shown to positively impact cognitive function, mental health, loneliness, and overall quality of life, particularly among older adults. For cancer patients, it is recommended that tailored home care services, including regular health check-ups, medication management, daily living assistance, and psychological support, be offered. Customized care plans can help address each patient’s unique needs, promoting physical and mental well-being.

This study has several limitations. It relied on patients’ self-reports, which may be subject to reporting bias. Additionally, although the study revealed correlations between variables, it was not able to clearly establish causal relationships. To enhance the accuracy of the research, future studies should consider combining the use of objective indicators and third-party assessment methods to enhance the reliability of the results; and conducting long-term follow-up studies to gain a deeper understanding of the dynamic changes in patients’ quality of life.

This study utilized SEM analysis to reveal the interactive relationships between family social support, psychological status, and quality of life in cancer patients receiving home care. The research found that family social support had a significant positive impact on the quality of life of these patients, with psychological status partially mediating this relationship. Specifically, family social support helps improve the psychological health of patients and reduces negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression, thereby indirectly enhancing their quality of life.

| 1. | Chen YB, Bao HS, Hu TT, He Z, Wen B, Liu FT, Su FX, Deng HR, Wu JN. Comparison of comfort and complications of Implantable Venous Access Port (IVAP) with ultrasound guided Internal Jugular Vein (IJV) and Axillary Vein/Subclavian Vein (AxV/SCV) puncture in breast cancer patients: a randomized controlled study. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pizzuti G, Cassani C, Bottazzi A, Ruggieri A, Della Valle A, Dionigi F, Anghelone CAP, Sgarella A, Ferrari A. Impact of totally implanted venous access port placement on body image in women with breast cancer. J Vasc Access. 2024;25:673-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Song X, Chen S, Dai Y, Sun Y, Lin X, He J, Xu R. A novel incision technique of a totally implanted venous access port in the upper arm for patients with breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21:162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Oh SB, Park K, Kim JJ, Oh SY, Jung KS, Park BS, Son GM, Kim HS, Kim DH, Jung HJ, Lee SS. Safety and feasibility of 3-month interval access and flushing for maintenance of totally implantable central venous port system in colorectal cancer patients after completion of curative intended treatments. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e24156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cai Y, Li Y, Deng Y, Ye J, Kang L, Zhang X, Deng Y, Huang M. [Upper arm vein versus subclavian vein for totally implantable venous access ports for patients with gastrointestinal malignancy: a retrospective comparison of complications]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015;18:1002-1005. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Xiao SP, Xiong B, Chu J, Li XF, Yao Q, Zheng CS. Fracture and migration of implantable venous access port catheters: Cause analysis and management of 4 cases. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2015;35:763-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ikhile D, Ford E, Glass D, Gremesty G, van Marwijk H. A systematic review of risk factors associated with depression and anxiety in cancer patients. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0296892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aprilianto E, Lumadi SA, Handian FI. Family social support and the self-esteem of breast cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Public Health Res. 2021;10:2234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ezrati-Vinacour R, Levin I. The relationship between anxiety and stuttering: a multidimensional approach. J Fluency Disord. 2004;29:135-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55:610-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 618] [Cited by in RCA: 1148] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9802] [Cited by in RCA: 11461] [Article Influence: 358.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Erdemir A, Rasa HK. Impact of central venous port implantation method and access choice on outcomes. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:116-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | van Leeuwaarde RS, González-Clavijo AM, Pracht M, Emelianova G, Cheung WY, Thirlwell C, Öberg K, Spada F. A Multinational Pilot Study on Patients' Perceptions of Advanced Neuroendocrine Neoplasms on the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-GINET21 Questionnaires. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Davda J, Kibet H, Achieng E, Atundo L, Komen T. Assessing the acceptability, reliability, and validity of the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) in Kenyan cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021;5:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Koch M, Gräfenstein L, Karnosky J, Schulz C, Koller M. Psychosocial Burden and Quality of Life of Lung Cancer Patients: Results of the EORTC QLQ-C30/QLQ-LC29 Questionnaire and Hornheide Screening Instrument. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:6191-6197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Poikonen-Saksela P, Kolokotroni E, Vehmanen L, Mattson J, Stamatakos G, Huovinen R, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Blomqvist C, Saarto T. A graphical LASSO analysis of global quality of life, sub scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 instrument and depression in early breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2022;12:2112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Papadopoulou A, Govina O, Tsatsou I, Mantzorou M, Mantoudi A, Tsiou C, Adamakidou T. Quality of life, distress, anxiety and depression of ambulatory cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Med Pharm Rep. 2022;95:418-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sebri V, Durosini I, Triberti S, Pravettoni G. The Efficacy of Psychological Intervention on Body Image in Breast Cancer Patients and Survivors: A Systematic-Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:611954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Morales-Sánchez L, Luque-Ribelles V, Gil-Olarte P, Ruiz-González P, Guil R. Enhancing Self-Esteem and Body Image of Breast Cancer Women through Interventions: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Choi J, Kim S, Choi M, Hyung WJ. Factors affecting the quality of life of gastric cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:3215-3224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chen X, Wu C, Bai D, Gao J, Hou C, Chen T, Zhang L, Luo H. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients in Asia: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Front Oncol. 2022;12:954179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |