Published online Feb 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i2.101595

Revised: November 23, 2024

Accepted: December 23, 2024

Published online: February 19, 2025

Processing time: 116 Days and 6.4 Hours

Increasing evidence has shown an increased risk of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in left-behind children and adolescents (LBCAs). However, a systematic summary of studies comparing the risk of NSSI between LBCAs and non-LBCAs in China is lacking.

To investigate the risk of NSSI among LBCAs in China.

We performed a systematic search of Embase, PubMed, and Web of Science from initiation to October 25, 2024, for all relevant studies of NSSI and LBCAs. The effect sizes were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to further confirm the stability of the fin

A total of 10 studies with 165276 children and adolescents were included in this study. LBCAs had significantly higher rates of NSSI compared with non-LBCAs (OR = 1.33, 95%CI: 1.19-1.49), with high heterogeneity observed (I2 = 77%, P < 0.001). Further sensitivity analyses were consistent with the primary analysis (OR = 1.29, 95%CI: 1.21-1.39, I2 = 0%).

LBCAs are found to be at an increased risk of NSSI compared with children and adolescents of non-migrants. More attention and intervention are urgently needed for LBCAs, especially those living in developing countries.

Core Tip: This study highlights the elevated risk of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) among left-behind children and adolescents (LBCAs) compared to their peers from non-migrant families. Using a meta-analysis of 165276 participants, we found a significant association between LBCAs and NSSI, with odds ratios indicating a 32% higher risk. These findings emphasize the need for targeted interventions, particularly in developing countries, to support the mental health of LBCAs and reduce NSSI risk.

- Citation: Zheng Q, Chen XC, Deng YJ, Ji YJ, Liu Q, Zhang CY, Zhang TT, Li LJ. Non-suicidal self-injury risk among left-behind children and adolescents in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(2): 101595

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i2/101595.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i2.101595

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), defined as the deliberate self-inflicted damage of one’s own body (such as cutting, scratching, or burning) without suicidal intent, is a growing mental health problem among adolescents[1,2]. The global prevalence of NSSI is estimated to be 17.2% among adolescents and 5.5% among adults[3], while the estimated prevalence among Chinese adolescents is 22.37%[4]. Several studies on adolescent suicide have indicated that NSSI is associated with an increased risk of future suicide[5-7]. According to existing studies, NSSI is the result of multiple interactions among genetic, biological, physiological, psychological, social, and cultural factors[8]. Thus, identifying risk factors for NSSI is essential for early screening and prevention of mental health issues among children and adolescents. In recent years, the special group of left-behind children and adolescents (LBCAs) in low- and middle-income countries has become a serious social issue and has attracted increasing attention[9]. According to statistics, there are over 61 million children left behind by one or both migrant parents in China, accounting for 38% of all rural children[10]. In addition, in a recent meta-analysis, LBCAs are at an increased risk of conduct disorder, substance use, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation compared with children of non-migrant parents[11], which has a substantial impact not only on the children themselves but also on their families and the whole society.

Empirical evidence consistently suggests that parental migration can increase the risk of NSSI among LBCAs. A recent study on 9450 adolescents showed that the incidence of NSSI among LBCAs (6.8%) is significantly higher than that among non-LBCAs (5.1%)[12]. Another study also indicated that LBCAs were at a significantly increased risk of NSSI[13]. The significantly higher risk of NSSI among LBCAs may be explained by the evolutionary models incorporating life history theory[14,15]. According to the life history theory, individuals living in adverse environments tend to develop fast life history strategies characterized by impulsivity, risk-taking, poor control, and low tolerance[16]. They favor short-term over long-term gains and are more likely to engage in risk-taking behaviors, such as NSSI, as the coping mechanism to adapt to the adverse environment[14,15]. For LBCAs, parental absence represents an environmental adversity that severely threatens’ their safety[15,17], contributing to the development of fast life history strategies and thus leading to a higher risk of NSSI. Despite the increasing evidence of the positive association between parental migration and NSSI among LBCAs, a systematic summary of studies comparing the risk of NSSI between LBCAs and those with non-migrant parents in China is lacking. Thus, we performed this meta-analysis to investigate the risk of NSSI among LBCAs based on the available epidemiological comparative studies.

We searched PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science from inception to October 25, 2024, using a combination of MeSH terms and keyword terms. The full search terms used in the three databases are available in Supplementary Table 1.

Two reviewers independently assessed the titles and abstracts and then screened the full text of potentially relevant articles. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) The research subjects were left-behind children or adolescents in China; (2) The study design included cross-sectional surveys, longitudinal studies, or retrospective study designs; (3) The study provided sufficient NSSI behavior data, allowing for the extraction of relevant statistical results; and (4) The study was published in a peer-reviewed journal or other credible publication. The exclusion criteria included: (1) Studies that did not clearly report NSSI behavior; (2) Studies where the subjects were not left-behind children; (3) Non-empirical research, such as commentaries, book chapters, animal studies, editorials, case reports, review articles, and articles published in languages other than English; (4) Articles where valid data couldn’t be extracted, such as those lacking statistical results or sample size information; and (5) Studies with low research quality due to significant bias or data errors. Any disagreement between the reviewers was to be resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

Data extraction was performed in triplicate using a standard form including the following information: first author, year of publication, study design, numbers of cases and controls, participant characteristics (age and sex), the definition of left-behind children or adolescents, and the assessment to measure NSSI (Supplementary Table 2). For any important information that was missing, the corresponding authors were contacted by email.

The risk of bias was assessed using the adapted Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale. Studies at a high or unclear risk of bias in five or more domains were classified as having a high risk of bias. Funnel plots were used to visually assess the risk of publication bias.

Continuous variables were presented using mean difference and 95% confidence intervals (CI), while binary variables were presented with odds ratio (OR) and 95%CI. The I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test were used to evaluate the heterogeneity, with I2 > 50% and P ≤ 0.1 suggesting significant heterogeneity. The random effects model was applied to pool the effect sizes if significant heterogeneity was present (I2 > 50%); otherwise, the fixed-effect model was applied as a default. Funnel plots were applied to assess publication bias. If significant heterogeneity was observed, sensitivity analyses should be further conducted to explore the source of heterogeneity. All analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) 5.3 software.

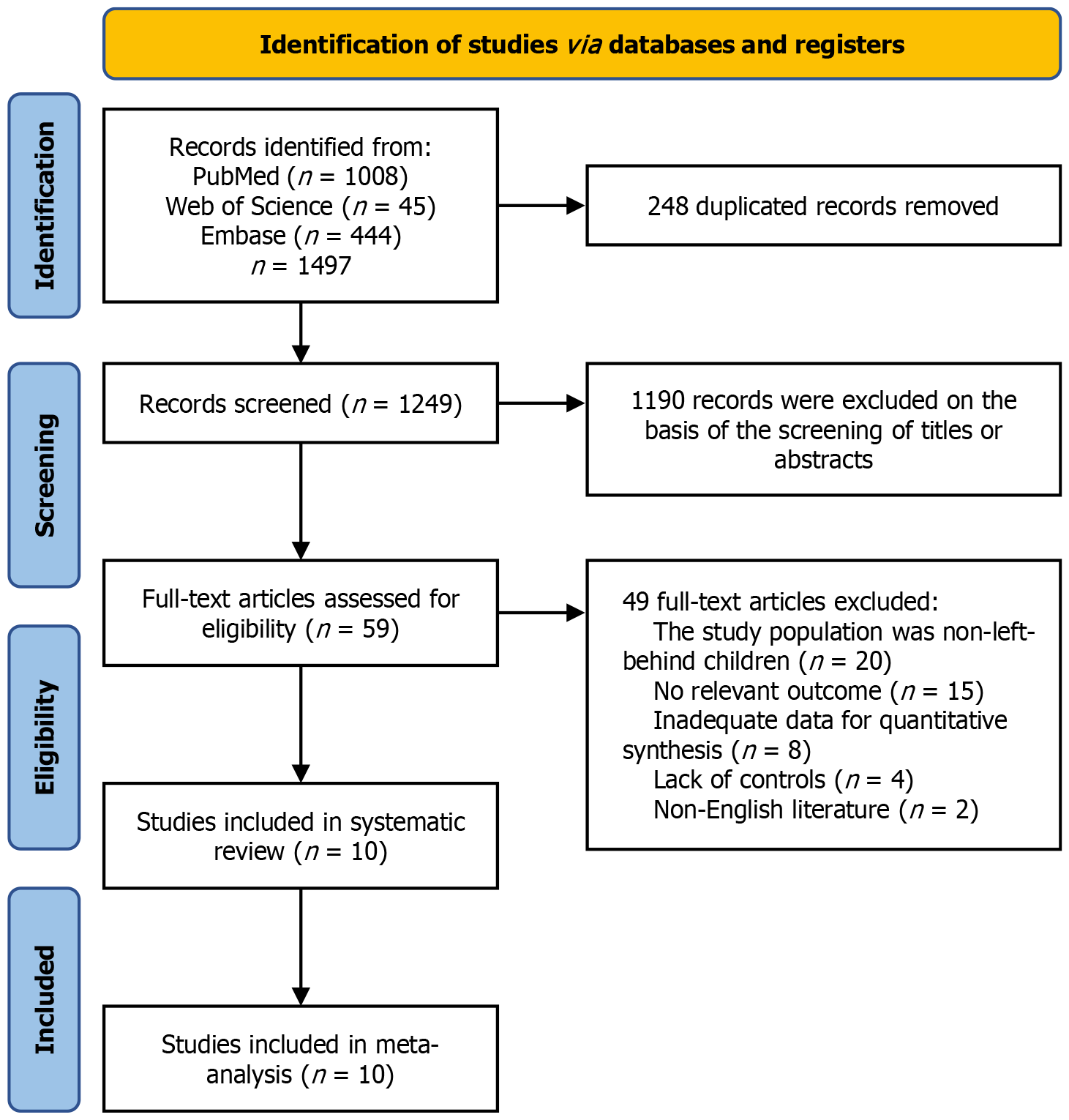

We initially identified 1497 records from the three database searches. After removing 248 duplicated records and screening 1249 titles and abstracts as well as 59 full-test articles, 10 eligible studies were included[12,13,18-25] in the final quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) (Figure 1).

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized (Supplementary Table 2). All the included studies were conducted in China and published between 2020 and 2024. A total of 167631 individuals (n = 41560 LBCAs, n = 126071 children and adolescents of non-migrants) from China were included in the present study. All the studies provided detailed definitions of LBCAs except for one[18], which provided no explicit definition. The proportion of male participants ranged from 50.3% to 55.4%, and their ages ranged from 7 years to 18 years. All studies used standardized self-injury behavior assessment tools, such as the most commonly used assessment scales to measure NSSI was the Ottawa Self-injury Inventory (n = 2), followed by the Functional Assessment of Self-mutilation (n = 1), the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (n = 1), and self-administered questionnaires or interviews (n = 6).

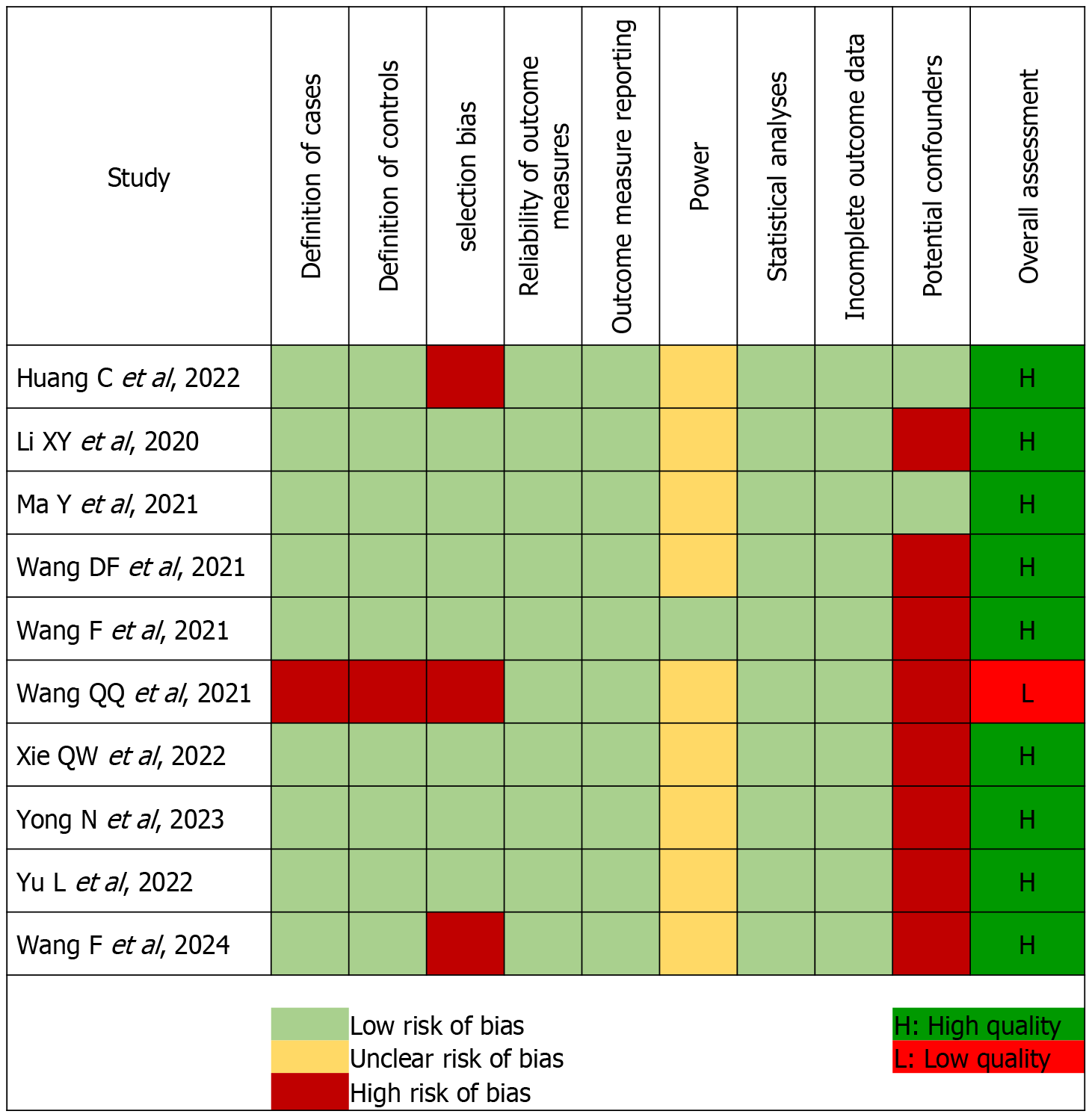

The quality assessment of all the studies according to the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale is presented (Figure 2). Only one of the 10 included studies had a high or unclear risk of bias across five or more domains[18]. The remaining 9 studies were found to be of high quality, indicating the overall quality of the present study was high.

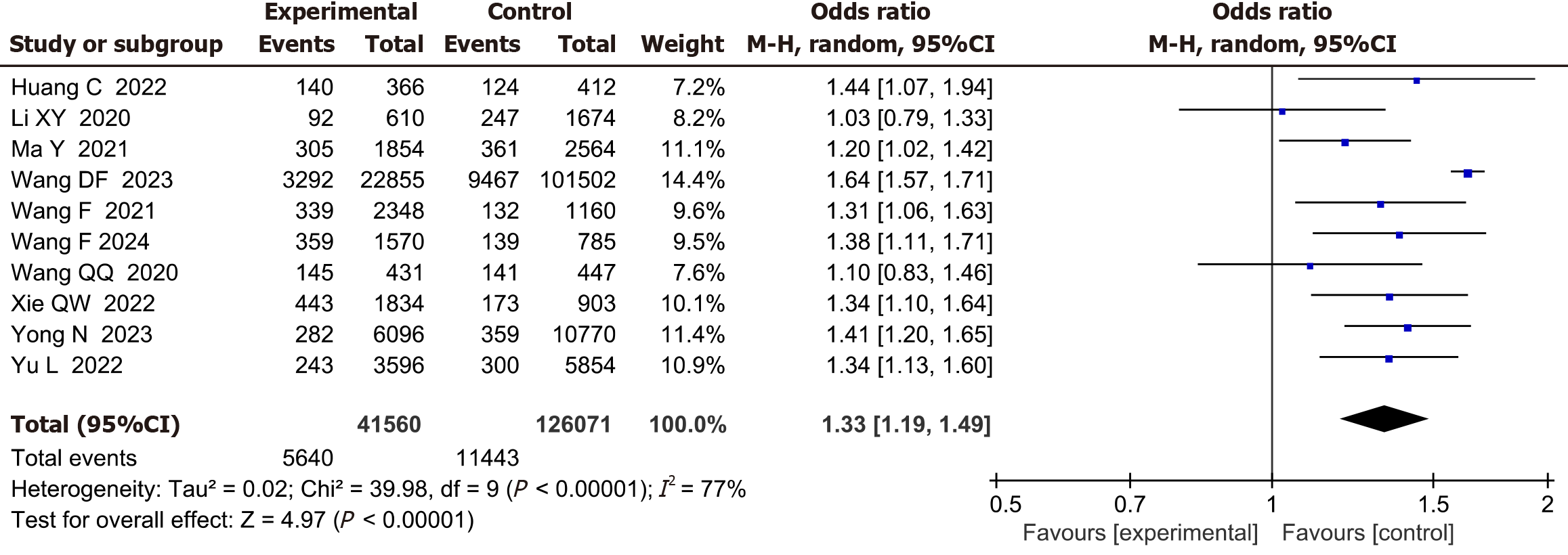

All 10 studies (involving a total of 167631 participants) compared the incidence of NSSI between LBCAs and the children and adolescents of non-migrants. Substantial heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 77%, P < 0.001). Results from a random effects model showed a significantly higher rate of NSSI among LBCAs, compared with children and adolescents of non-migrants (OR = 1.33, 95%CI: 1.19-1.49, Z = 4.97, P < 0.001) (Figure 3).

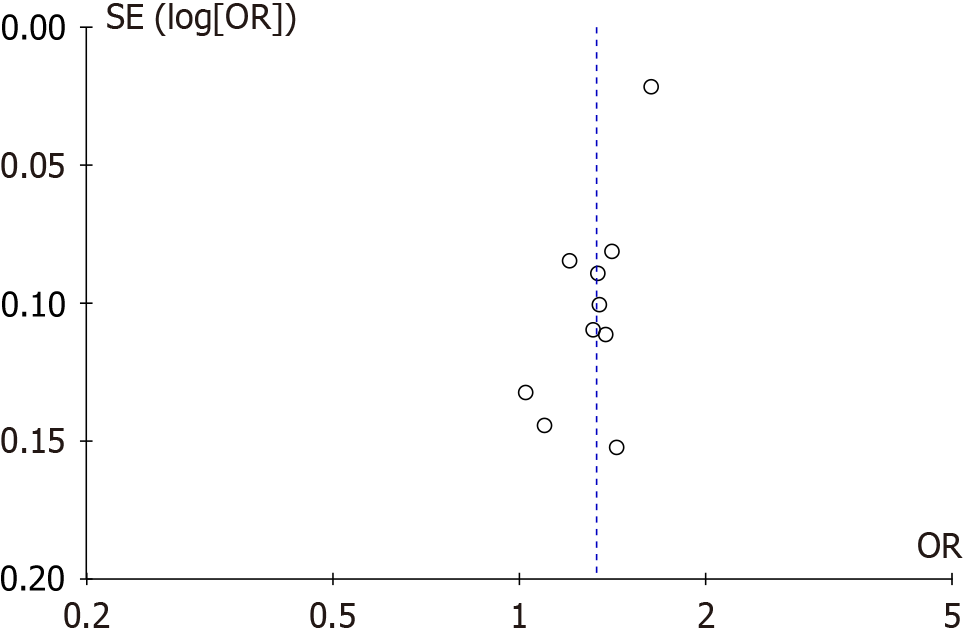

Publication bias analysis was conducted using the prevalence of NSSI as an index. In the funnel diagram, the dots were not asymmetrically distributed, suggesting a possibility of publication bias (Figure 4).

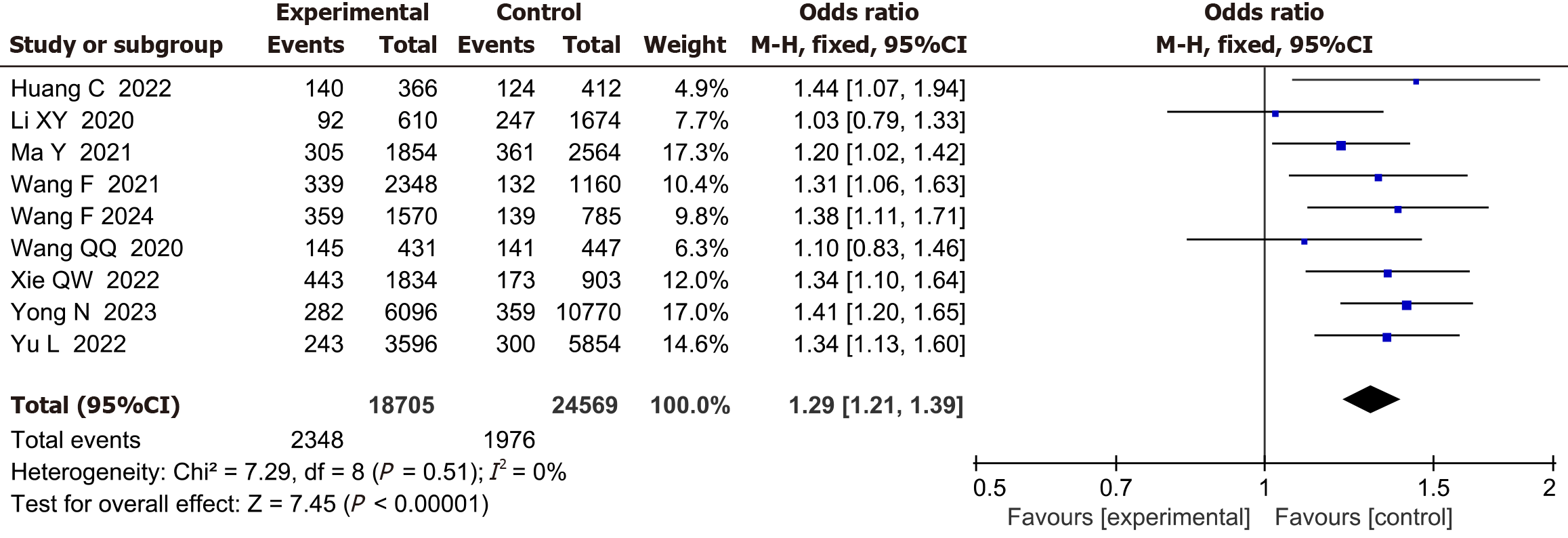

Since substantial heterogeneity was detected among the studies, sensitivity analysis was further performed by removing each study at one time and recalculating the combined estimate on the remaining studies. The results suggested that the study by Wang et al[20] significantly contributed to the overall heterogeneity and the overall heterogeneity was significantly reduced after the removal of this study (P = 0.51, I2 = 0%). Results from sensitivity analysis using a random effects model were consistent with those of our primary analyses (OR = 1.29, 95%CI: 1.21-1.39, Z = 7.45, P < 0.001) (Figure 5), which confirmed that LBCAs had significantly higher rates of NSSI compared with children and adolescents of non-migrants.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to investigate the risk of NSSI among LBCAs as compared to non-LBCAs controls in China. In the present study, a total of 10 studies involving 165276 children or adolescents were identified, and we found that LBCAs were at a 33% increased risk of NSSI compared with those with non-migrant parents. Despite the heterogeneity detected in the primary analysis, sensitivity analysis confirmed the stability of our findings. Noteworthily, sensitivity analyses showed that Wang et al[20] contributed to a high proportion of the overall heterogeneity, which may be explained by the specific characteristics of this study. Unlike other studies that were mainly focused on LBCAs in rural areas, Wang et al’s study[20] was conducted in urban areas of Shenzhen City in Guangdong province, which are among the most developed cities in China. Although urban LBCAs are relatively less studied, they are found to have greater susceptibility to mental health difficulties and exhibit significantly more behavior problems than rural LBCAs. The worse psycho-behavioral health outcomes among urban LBCAs may be explained by multiple reasons, such as the striking disparities and poverty within cities and parents’ higher expectation for academic achievement, which may contribute to higher levels of psychological distress, potentially leading to a higher risk of NSSI. Despite the high heterogeneity of Wang et al’s from other studies[20], subsequent sensitivity analysis by removing this study still showed a significantly increased risk of NSSI in LBCAs than in their counterparts, confirming the stability of the association between LBCAs and NSSI. These findings indicate the need for raising public attention to the psychological and behavioral health of LBCAs, with equal focus on LBCAs from both rural and urban areas.

Labor migration and the health of LBCAs have become a global concern, especially in low- and middle-income countries[26,27], However, this concern has never been given sufficient attention. In our meta-analysis, all the included studies were from China. Data from other countries, especially from developing countries, is still insufficient. Our findings are in line with those of a previous meta-analysis of the health of LBCAs[11]. Based on 111 studies, Fellmeth et al[11] assessed the impact of parental migration on the health of 264967 children and adolescents, which suggested that LBCAs were at an increased risk of anxiety [relative risk (RR): 1.85], depression (RR: 1.52), and suicidal ideation (RR: 1.70), compared with children of non-migrants[11]. In recent years, NSSI in children and adolescents has attracted increasing attention[28,29]. Consistent with previous studies[24,30], we found a significant impact of parental migration on NSSI among children and adolescents (OR = 1.33, P < 0.001).

The mechanism of the high prevalence of NSSI among LBCAs is still under exploration. Some studies found that LBCAs are more likely to have negative emotions (depression and anxiety) and experience negative life events[31-33], which were considered risk factors for NSSI[34-36]. Similarly, it has also been reported that LBCAs are more likely to be bullied and have a lower level of self-esteem[37-39], which might contribute to their NSSI[40,41]. The marital status of their parents (e.g., single-parent family and reconstituted family), as well as lack of parent-child communication, might also increase the risk of NSSI[42,43]. Notably, some of the included studies suggested that left-behind girls were generally more susceptible to NSSI than left-behind boys[12,20]. A recent meta-analysis involving 43 studies also indicated that the prevalence of NSSI in females was significantly higher than that in males (25.4% vs 22.0%, P < 0.001)[44]. This might be explained by the gender differences in brain development, biological factors (such as hormone differences), and emotion processing (such as rumination), which might have contributed to the increased risk of NSSI among left-behind girls[45,46]. In addition, childhood and adolescence are critical periods for the nervous system and cognitive development. Still, during this process, children and adolescents often make suboptimal decisions, which may be associated with an increased risk of NSSI[47,48]. Therefore, psychological intervention and emotional support are essential for LBCAs, especially for those growing up in single-parent or reconstituted families, to reduce the risk of NSSI.

There are several strengths of our meta-analysis. First, this is the first meta-analysis to investigate the risk of NSSI among LBCAs. Second, the high-quality studies and the relatively large sample sizes contributed to a higher statistical reliability of our results. Third, although heterogeneity was observed in the pooled analysis, the results were consistent in the subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis, with no significant heterogeneity. However, there are also several limitations. The literature searches were limited to those published in the English language, and all the included studies were from China, which might have introduced publication bias. Furthermore, the definition of parental migration was not fully consistent across different studies. Finally, all the studies included in this meta-analysis were observational studies, which precluded us from exploring causal relationships.

The finding that LBCAs are at a significantly higher risk of NSSI than children and adolescents with non-migrant parents is consistent with the abundant literature and aligns with the life history theory. This study carries important implications for the prevention and intervention of NSSI among LBCAs. According to the life history theory, improving parent-child cohesion and relationship can help create a safe and stable environment for the children, which can foster slow life history strategies that focus on long-term benefits instead of short-term benefits in fast life history strategies[15]. Our findings provide critical guidance for educators and psychologists to develop targeted and effective school-based mental health programs to address the specific needs of LBCAs. It is suggested that migrant parents should be encouraged and empowered to actively participate in their children’s education and provide sufficient emotional support to their children. Schools should promote positive interaction and communication between migrant parents and children to strengthen family cohesion and function, which is essential to the prevention of NSSI among LBCAs and the enhancement of their psychological and behavioral health.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis demonstrated an increased risk of NSSI among LBCAs, compared with children and adolescents of non-migrants. More attention and intervention are urgently needed for LBCAs, especially those in developing countries.

Thank you to all the participants who have contributed to the studies, and thank all the researchers whose work contributed to this systematic review and meta-analysis.

| 1. | Zetterqvist M, Perini I, Mayo LM, Gustafsson PA. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Disorder in Adolescents: Clinical Utility of the Diagnosis Using the Clinical Assessment of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Disorder Index. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hamza CA, Willoughby T. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and Suicidal Risk Among Emerging Adults. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:411-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, St John NJ. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44:273-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1186] [Cited by in RCA: 952] [Article Influence: 86.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lang J, Yao Y. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in chinese middle school and high school students: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Poudel A, Lamichhane A, Magar KR, Khanal GP. Non suicidal self injury and suicidal behavior among adolescents: co-occurrence and associated risk factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Eckenrode J, Purington A, Baral Abrams G, Barreira P, Kress V. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a gateway to suicide in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:486-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Viner RM, Haller DM, Bose K, Vos T, Ferguson J, Mathers CD. Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2009;374:881-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 748] [Cited by in RCA: 705] [Article Influence: 44.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kaess M, Hooley JM, Klimes-Dougan B, Koenig J, Plener PL, Reichl C, Robinson K, Schmahl C, Sicorello M, Westlund Schreiner M, Cullen KR. Advancing a temporal framework for understanding the biology of nonsuicidal self- injury: An expert review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;130:228-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mcauliffe M, Ruhs M. Chapter 1 – Making sense of migration in an increasingly interconnected world. World Migration Report. 2018;2018. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Yuan P, Wang L. Migrant workers: China boom leaves children behind. Nature. 2016;529:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fellmeth G, Rose-Clarke K, Zhao C, Busert LK, Zheng Y, Massazza A, Sonmez H, Eder B, Blewitt A, Lertgrai W, Orcutt M, Ricci K, Mohamed-Ahmed O, Burns R, Knipe D, Hargreaves S, Hesketh T, Opondo C, Devakumar D. Health impacts of parental migration on left-behind children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;392:2567-2582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 42.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yu L, Zhao J, Zhao T, Xiao Y, Ou Q, He J, Luo J, Zhong Y, Cen Y, Luo W, Yang J, Deng Y, Zhang J, Luo J. Multicenter analysis on the non-suicidal self-injury behaviors and related influencing factors-A case study of left-behind children in northeastern Sichuan. J Affect Disord. 2023;320:161-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xie Q, Zhao G, Lu J, Chen R, Xu J, Wang M, Akezhuoli H, Wang F, Zhou X. Mental Health Problems amongst Left-behind Adolescents in China: Serial Mediation Roles of Parent-Adolescent Communication and School Bullying Victimisation. Brit J Soc Work. 2023;53:994-1018. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Chang L, Lu HJ. Resource and extrinsic risk in defining fast life histories of rural Chinese left-behind children. Evol Hum Behav. 2018;39:59-66. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ellis BJ, Del Giudice M, Dishion TJ, Figueredo AJ, Gray P, Griskevicius V, Hawley PH, Jacobs WJ, James J, Volk AA, Wilson DS. The evolutionary basis of risky adolescent behavior: implications for science, policy, and practice. Dev Psychol. 2012;48:598-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 439] [Cited by in RCA: 450] [Article Influence: 34.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Brüne M. Borderline Personality Disorder: Why 'fast and furious'? Evol Med Public Health. 2016;2016:52-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bowlby J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds. I. Aetiology and psychopathology in the light of attachment theory. An expanded version of the Fiftieth Maudsley Lecture, delivered before the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 19 November 1976. Br J Psychiatry. 1977;130:201-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1342] [Cited by in RCA: 932] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang Q, Liu X. Peer Victimization and Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Among Chinese Left-Behind Children: The Moderating Roles of Subjective Socioeconomic Status and Social Support. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36:11165-11187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang F, Wang Y, Liu S, Cui L, Li F, Wang X. The impact of parental migration patterns, timing, and duration on the health of rural Chinese children. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1439568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang D, Ma Z, Fan Y, Chen H, Liu W, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Fan F. Associations Between Family Function and Non-suicidal Self-injury Among Chinese Urban Adolescents with and Without Parental Migration. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yong N, Luo J, Luo JM, Yao YS, Wu J, Yang H, Li JD, Yang S, Leng YY, Zheng HC, Fan Y, Hu YD, Ma J, Tan YW, Pan JY. Non-suicidal self-injury and professional psychological help-seeking among Chinese left-behind children: prevalence and influencing factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Huang C, Yuan Q, Ge M, Sheng X, Yang M, Shi S, Cao P, Ye M, Peng R, Zhou R, Zhang K, Zhou X. Childhood Trauma and Non-suicidal Self-Injury Among Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Psychological Sub-health. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:798369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Li X, Chen F, Lin Y, Jia Z, Tucker W, He J, Cui L, Yuan Z. Research on the Relationships between Psychological Problems and School Bullying and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among Rural Primary and Middle School Students in Developing Areas of China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ma Y, Guo H, Guo S, Jiao T, Zhao C, Ammerman BA, Gazimbi MM, Yu Y, Chen R, Wang HHX, Tang J. Association of the Labor Migration of Parents With Nonsuicidal Self-injury and Suicidality Among Their Offspring in China. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2133596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang F, Lu J, Lin L, Cai J, Xu J, Zhou X. Impact of parental divorce versus separation due to migration on mental health and self-injury of Chinese children: a cross sectional survey. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2021;15:71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Antia K, Boucsein J, Deckert A, Dambach P, Račaitė J, Šurkienė G, Jaenisch T, Horstick O, Winkler V. Effects of International Labour Migration on the Mental Health and Well-Being of Left-Behind Children: A Systematic Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mcauliffe M, Khadria B. 1 Report overview: Providing perspective on migration and mobility in increasingly uncertain times. World Migration Report. 2020;2020. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Franzen M, Keller F, Brown RC, Plener PL. Emergency Presentations to Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and Suicidality. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Plener PL, Kaess M, Schmahl C, Pollak S, Fegert JM, Brown RC. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in Adolescents. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lan T, Jia X, Lin D, Liu X. Stressful Life Events, Depression, and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Among Chinese Left-Behind Children: Moderating Effects of Self-Esteem. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tang W, Wang G, Hu T, Dai Q, Xu J, Yang Y, Xu J. Mental health and psychosocial problems among Chinese left-behind children: A cross-sectional comparative study. J Affect Disord. 2018;241:133-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Liang Y, Wang L, Rui G. Depression among left-behind children in China. J Health Psychol. 2017;22:1897-1905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cheng J, Sun YH. Depression and anxiety among left-behind children in China: a systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41:515-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jiang Z, Wang Z, Diao Q, Chen J, Tian G, Cheng X, Zhao M, He L, He Q, Sun J, Liu J. The relationship between negative life events and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) among Chinese junior high school students: the mediating role of emotions. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2022;21:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Xiao Q, Song X, Huang L, Hou D, Huang X. Association between life events, anxiety, depression and non-suicidal self-injury behavior in Chinese psychiatric adolescent inpatients: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1140597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Jiao T, Guo S, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xie X, Ma Y, Chen R, Yu Y, Tang J. Associations of depressive and anxiety symptoms with non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal attempt among Chinese adolescents: The mediation role of sleep quality. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1018525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Zhang H, Chi P, Long H, Ren X. Bullying victimization and depression among left-behind children in rural China: Roles of self-compassion and hope. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;96:104072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zhang H, Zhou H, Cao R. Bullying Victimization Among Left-Behind Children in Rural China: Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36:NP8414-NP8430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Yu BL, Li J, Liu W, Huang SH, Cao XJ. The Effect of Left-Behind Experience and Self-Esteem on Aggressive Behavior in Young Adults in China : A Cross-Sectional Study. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37:1049-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Forrester RL, Slater H, Jomar K, Mitzman S, Taylor PJ. Self-esteem and non-suicidal self-injury in adulthood: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:172-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Serafini G, Aguglia A, Amerio A, Canepa G, Adavastro G, Conigliaro C, Nebbia J, Franchi L, Flouri E, Amore M. The Relationship Between Bullying Victimization and Perpetration and Non-suicidal Self-injury: A Systematic Review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2023;54:154-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Zhou J, Zhang J, Huang Y, Zhao J, Xiao Y, Zhang S, Li Y, Zhao T, Ma J, Ou N, Wang S, Ou Q, Luo J. Associations between coping styles, gender, their interaction and non-suicidal self-injury among middle school students in rural west China: A multicentre cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:861917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Nemati H, Sahebihagh MH, Mahmoodi M, Ghiasi A, Ebrahimi H, Barzanjeh Atri S, Mohammadpoorasl A. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Its Relationship with Family Psychological Function and Perceived Social Support among Iranian High School Students. J Res Health Sci. 2020;20:e00469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Xiao Q, Song X, Huang L, Hou D, Huang X. Global prevalence and characteristics of non-suicidal self-injury between 2010 and 2021 among a non-clinical sample of adolescents: A meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:912441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Bresin K, Schoenleber M. Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;38:55-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Westlund Schreiner M, Klimes-Dougan B, Begnel ED, Cullen KR. Conceptualizing the neurobiology of non-suicidal self-injury from the perspective of the Research Domain Criteria Project. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;57:381-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Plener PL, Bubalo N, Fladung AK, Ludolph AG, Lulé D. Prone to excitement: adolescent females with Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) show altered cortical pattern to emotional and NSS-related material. Psychiatry Res. 2012;203:146-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Plener PL, Schumacher TS, Munz LM, Groschwitz RC. The longitudinal course of non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm: a systematic review of the literature. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2015;2:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |