Published online Jan 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i1.100953

Revised: November 2, 2024

Accepted: November 26, 2024

Published online: January 19, 2025

Processing time: 109 Days and 0.6 Hours

Frailty has become a significant public health issue. The recent increase in the number of frail older adults has led to increased attention being paid to psychological care services in communities. The social isolation of pre-frail older adults can impact their psychological distress.

To explore the mediating effect of health literacy between social isolation and psychological distress among communitydwelling older adults with pre-frailty.

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted with 254 pre-frail older individuals aged 60 years and over. Social isolation, health literacy, and psycholo

The results showed that social isolation had an effect on health literacy among pre-frail older adults (β = 0.240, P < 0.001), social isolation impact on psychological distress pre-frail older adults (β = -0.415, P < 0.001); health literacy was identified effect on psychological distress among pre-frail older persons (β = -0.307, P < 0.001). Health literacy partially mediated the relationship between social isolation and psychological distress among community-dwelling older adults with pre-frailty, with a mediation effect of -0.074, accounting for 17.83% of the total effect.

Health literacy significantly affects the relationship between social isolation and psychological distress among

Core Tip: Older adults' combined frailty and social isolation should be addressed to prevent adverse health outcomes. Social isolation is negatively associated with health literacy. Health literacy is associated with psychological distress in older adults. This study identified a mediating role of health literacy between social isolation and psychological distress among pre-frail older adults. It is significant to develop intervention programs to foster social connection as well as health literacy in the future for pre-frail older persons with psychological distress.

- Citation: Fang J, Li LH, He MQ, Ji Y, Lu DY, Zhang LB, Yao JL. Mediating role of health literacy in the relationship between social isolation and psychological distress among pre-frail older adults. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(1): 100953

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i1/100953.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i1.100953

Population aging poses an insupportable burden on the healthcare system globally. Frailty is a common functional impairment in older adults resulting from aging-related conditions. Physical frailty (hereafter as ‘frailty’) refers to a nonspecific syndrome of declined physiological reserve, increased vulnerability, and decreased resilience of older persons, leading to various adverse health outcomes such as falls, hospitalizations, disabilities, and mortality[1]. Various frailty scales can stratify frailty into three degrees: No frailty, pre-frailty, and frailty. However, frailty and pre-frailty are reversible, and it is more meaningful to intervene in the pre-frailty to delay the frailty progression. Pre-frailty prevalence was 50.5% among community-dwelling older adults, nearly four times the prevalence of frailty[2]. Screening pre-frail older populations susceptible to intervention could prevent or delay frailty and even reverse the state from pre-frail to robust[3]. Psychological distress is a condition characterized by depressive symptoms, anxiety, functional impairment, personality traits, and behavioral problems[4]. Severe psychological distress was associated with increased risks of frailty[5].

Older adults with social isolation are more likely to develop pre-frailty from robust[6]. To prevent adverse health outcomes, combined frailty and social isolation among older adults should be addressed[7]. Social isolation is defined as decreased social activity, restricted social network size, and absence of social support[8]. Social isolation influences health behaviors, triggers conditions like stress and depression, and seriously threatens the physical and mental health of older persons. Social isolation is negatively associated with health literacy[9]. It might limit opportunities for individuals to improve health literacy skills and impede the adaptation and modification of health behaviors[10,11]. Social isolation was positively associated with psychological distress[12].

Health literacy was associated with pre-frailty and frailty among community-dwelling older adults[13]. Health literacy refers to “the personal, cognitive, and social skills that determine the ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information to promote and maintain good health”[14]. It is well established that limited health literacy is associated with poor mental health conditions in older persons, including psychological distress[15,16]. It was reported that increased health literacy could reduce psychological dysfunction[17].

Based on previous empirical evidence that perceived social isolation is negatively associated with health literacy and positively associated with psychological distress, health literacy is negatively associated with psychological distress. A previous study explored the mediating effect of health literacy between chronic disease and psychological distress among older adults by applying Cognitive Behavior Theory (CBT)[16]. It pointed out that health literacy had a partial mediating effect on the relationship between the presence of chronic disease and psychological distress among older adults[16]. However, the relationship between these three variables still needs to be clarified. More research is needed to explore the influence pathways of these three variables in the current literature, particularly in older adults with pre-frailty.

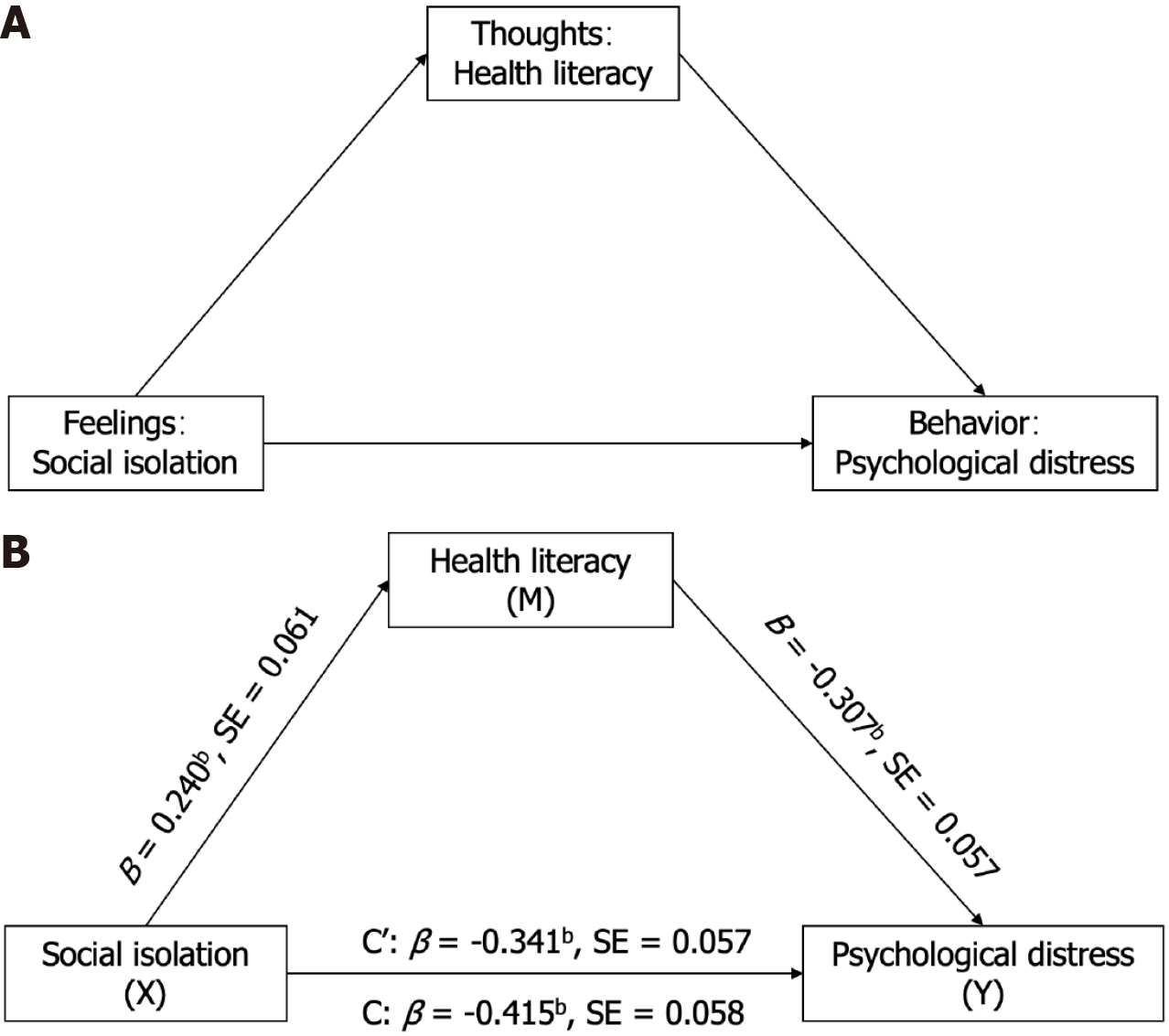

CBT, which mainly includes feelings, thoughts, and behavior constructs, was used to explain better the relationship between the three variables among older adults[18]. Pre-frail older adults with social isolation may feel lonely, and social isolation constitutes feelings in CBT in this study. Health literacy constitutes thoughts in CBT, the cognitive ability to grasp and apply information to promote and maintain good health. Psychological distress is a condition that includes maladaptive behavior. Therefore, psychological distress constitutes behavior in CBT. In assumptions of CBT models, cognitive activity influences behavior; cognitive activity may be monitored and altered, and cognitive change can produce behavioral change. Consequently, the primary aim of this study was to identify the association between social isolation and psychological distress and to elucidate the mediating role of health literacy in pre-frail older community dwellers. This study's hypotheses are as follows: (1) Social isolation negatively influences Health literacy; (2) Social isolation positively influences health literacy and psychological distress; (3) Health literacy negatively influences psychological distress; and (4) Health literacy negatively mediates the relationship between social isolation and psychological distress (as shown in Figure 1A).

This observational cross-sectional study was conducted among older adults in Zhejiang Province, China. To participate in this study, the participants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) Pre-frail older adults, scored 1-2 according to the FRAIL Scale[19]; (2) Aged 60 years and older; (3) Clear consciousness, and no unmistakable language comprehension and expression disorders; and (4) Informed consent. This study excluded patients who had emergency conditions that required abrupt treatment.

Estimating the minimum sample size for structural equation modeling depends on the number of constructs included in the model[20]. A model containing five or fewer constructs requires a minimum sample size of 100. As this research included three constructs (social isolation, health literacy, and psychological distress), 300 questionnaires were distributed, and 280 questionnaires were collected, 254 of which were valid after quality control, for a valid response rate of 90.71%.

The survey was conducted between November 2023 and February 2024. Initially, this study used stratified sampling in Zhejiang province. Five cities (Hangzhou ranked first, Wenzhou third, Taizhou sixth, Huzhou eighth, and Lishui eleventh in 2023) were selected among 11 prefecture-level cities according to the Gross Domestic Product. Secondly, five community healthcare centers were selected conveniently in the five cities above. Eventually, investigators interviewed participants face-to-face at the community healthcare centers using convenience sampling. The questionnaires were distributed using the Questionnaire Star platform. The researcher offered guidance if the participants needed help completing the survey.

Participants were informed about the study’s aim, procedure, risks, benefits, and right to privacy, and participation was voluntary. This study received ethical approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of Huzhou University for conducting this study (approval number: 2023-06-27).

Demographic questionnaire: We collected data on participants’ age, gender, marital status, monthly income, and educational level. The personal factors were defined as follows: (1) Gender (male = 1, female = 2); (2) Marital status (married = 1, unmarried/divorced/widowed = 2); (3) Monthly income [0-1000 China Yuan (CNY); 1000-2999 CNY; 3000-4999 CNY; ≥ 5000 CNY]; and (4) Education level (below primary school = 1; primary school = 2; junior high school = 3; high school = 4; college or above = 5).

Lubben Social Network Scale: The social isolation level was assessed by the Lubben Social Network Scale-6 (LSNS-6)[21]. This scale includes six items with two dimensions (family network and friend network). Each item was rated on a six-level scale (total score range: 0-30). A lower score indicates a higher likelihood of social isolation; a score below 12 manifests social isolation. It was validated in the Chinese population with high reliability and validity[22].

Short-Form Health Literacy Questionnaire: 12-item Short-Form Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLS-SF12)[23] was used to measure Health literacy. It consists of 12 items for assessing three health domains: health care, disease prevention, and health promotion. Each item was scored from 1 to 4 points. The health literacy standardized index was calculated using the formula [index = (mean – 1) × (50/3)]. The index ranges from 0 to 50, where 0 represents the lowest health literacy level, and 50 is the highest. The Cronbach’s Alpha of the original and Chinese versions was 0.85[23] and 0.94[24], respectively.

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale: Psychological distress was measured by the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale-10 (K10). It is a self-rating scale that assesses the mental health status of individuals, such as anxiety and stress levels. Research has shown good reliability and validity of the Chinese version in the Chinese population[25]. This scale includes ten items. Each item scored from 1 to 5 points, with the total score ranging from 10 to 50. The higher scores indicate poorer mental health status.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 27.0 and PROCESS Macro 4.2. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze participants’ general demographic characteristics and scores on social isolation, health literacy, and psychological distress. Pearson's correlation analyses investigated the associations between health literacy, social isolation, and psychological distress. The mediating effect of health literacy was explored by PROCESS Model 4 while controlling for all statistically significant covariates identified in the general characteristics analysis. The significance of regression coefficients was assessed using the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap distribution (5000 iterations) with a 95%CI. Statistical significance was set at a P < 0.05. A biomedical statistician performed a statistical review of the study.

The general characteristics of 254 participants were provided in Table 1. The mean age of respondents was 72.44 years (SD = 5.80), and more than half were female (55.9%). Most respondents were married (82.7%), approximately two-fifths of the respondents earned 1000-2999 CNY monthly (41.3%), and nearly one-third of the respondents completed junior high school (33.1%).

| Variable | Percentage | K10 score | t/F | P value |

| Age | 1.611 | 0.202 | ||

| 60-69 | 89 (35.0) | 13.91 ± 5.73 | ||

| 70-79 | 144 (56.7) | 13.31 ± 3.82 | ||

| ≥ 80 | 21 (8.3) | 15.14 ± 4.54 | ||

| Gender | -1.792 | 0.074 | ||

| Male | 112 (44.1) | 13.11 ± 3.85 | ||

| Female | 142 (55.9) | 14.12 ± 5.16 | ||

| Marital status | -2.541 | 0.012 | ||

| Married | 210 (82.7) | 13.34 ± 4.67 | ||

| Unmarried/divorced/widowed | 44 (17.3) | 15.27 ± 4.18 | ||

| Monthly income (CNY) | 3.530 | 0.016 | ||

| 0-1000 | 33 (13.0) | 15.79 ± 5.61 | ||

| 1000-2999 | 105 (41.3) | 13.82 ± 4.48 | ||

| 3000-4999 | 69 (27.2) | 13.17 ± 4.38 | ||

| ≥ 5000 | 47 (18.5) | 12.60 ± 4.26 | ||

| Education level | 3.962 | 0.004 | ||

| Below primary school | 48 (18.9) | 15.75 ± 4.27 | ||

| Primary school | 69 (27.2) | 13.03 ± 4.05 | ||

| Junior high school | 84 (33.1) | 13.04 ± 3.62 | ||

| High school | 38 (15.0) | 14.29 ± 7.30 | ||

| College or above | 15 (5.9) | 12.00 ± 2.62 |

The average scores and standard deviations of the three scales are presented in Table 2. The study found that the average LSNS-6 score of the 254 participants was 19.37 ± 4.77 points, the average HLS-SF12 score was 28.72 ± 5.38, and the average K10 score was 13.67 ± 4.64 points.

| Scale | Mean | SD |

| LSNS-6 | 19.37 | 4.77 |

| HLS-SF12 | 28.72 | 5.38 |

| K10 | 13.67 | 4.64 |

Correlation analysis was performed on health literacy, social isolation, and psychological distress scores in older adults with pre-frailty (Table 3). LSNS-6 score positively correlated with the HLS-SF12 score (r = 0.273, P < 0.01) and exhibited negative correlations with psychological distress (r = -0.430, P < 0.01). Health literacy negatively correlated with psychological distress (r = -0.410, P < 0.01).

Health literacy was investigated as a potential mediator of the association between social isolation and psychological distress through Model 4 in PROCESS. Marital status, monthly income, and education level were set as covariates. The final structural equation output model presents the standardization path coefficient (Figure 1B). The regression equation was statistically significant (R2 = 0.349, F = 33.402, P < 0.001). The social isolation directly affects health literacy (β = 0.240, P < 0.001). Health literacy directly impacts psychological distress (β = -0.307, P < 0.001). Social isolation directly influences psychological distress (β = -0.341, P < 0.001). Health literacy mediates the relationship between social isolation and psychological distress (β = -0.074, P < 0.001), accompanied by a mediation effect ratio of 17.83%. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 4.

| Path | β | SE | 95%LLCI | 95%ULCI | Relative mediation effect |

| Total effect of X on Y | -0.415 | 0.058 | -0.529 | -0.300 | |

| Direct effect of X on Y | -0.341 | 0 .057 | -0.453 | -0.229 | 82.17% |

| Indirect effect (X→M→Y) | -0.074 | 0.030 | -0.139 | -0.025 | 17.83% |

This study investigated the potential mediating role of health literacy between social isolation and psychological distress. The results demonstrated that social isolation influenced psychological distress independently and partially through health literacy. These findings suggest that among pre-frail older adults, the higher the perceived social isolation, the lower the health literacy level, which further leads to psychological distress.

The present study’s findings indicate that the perceived psychological distress level among pre-frail older adults is elevated compared to the results reported by Anderson et al[26]. One possible explanation is that the study's respondents were older adults who participated in the Australian National Surveys of Mental Health and Well-being rather than older adults with pre-frailty. The results of this study revealed that the level of psychological distress among pre-frail older people was lower than that reported in the study conducted by Vasiliadis et al[27]. The possible reason is that the participants in that study were patients aged 65 years and over. It was demonstrated that psychological distress was positively associated with the risks of pre-frailty[5,28,29]. Primary health care should strengthen the screening and intervention of psychological distress among community pre-frail older adults.

In this study, social isolation was the significant factor that influenced health literacy among pre-frail older adults. This result was consistent with the previous study[30], which proved that social isolation increases an individual’s susceptibility to life stressors and increases the risk of depressive symptoms. It was also identified in a recent review that poor health literacy is related to poor social support and social isolation, as health literacy skills cannot be improved without social interactions[9].

This study found that social isolation was the factor that significantly influenced psychological distress among community-dwelling older persons with pre-frailty. This result was consistent with the previous study[12], which revealed a significant association between social isolation and psychological well-being among older adults. Social isolation is an important issue that has significant consequences for older adults’ mental health[31]. Therefore, it is critical to determine the relationship between social isolation and psychological distress among community-dwelling older persons with pre-frailty.

This study identified health literacy as a significant factor influencing psychological distress among pre-frail older adults. The finding is similar to the research findings that older persons with limited health literacy have barriers to gaining access to, understanding, and using health-related information and delay the use of mental health services, leading to psychological distress in Xi'an, China[16].

This study found that health literacy mediates between social isolation and psychological distress among community-dwelling older adults with pre-frailty. One study revealed the mediator of resilience in the relationship between social isolation and psychological well-being[12], and another study revealed loneliness as a mediator in the association between social isolation and psychological distress[32].

The strength of this study was focusing on pre-frail older adults, a rapidly growing vulnerable population worldwide. According to CBT, the mediating role of health literacy between social isolation and psychological distress is a significant finding. The findings of this study may lighten the psychological distress of pre-frail older adults. The findings from this study suggested that in addition to reducing social isolation, fostering health literacy should be considered when intervening in pre-frail older adults with psychological distress. Positive support in individuals' social networks can improve their ability to acquire, understand, and use medical information. Healthcare providers should provide measures to improve their health literacy under the guidance of theory.

The present study has some limitations despite focusing on community-dwelling older adults with pre-frailty, a rapidly growing vulnerable population. First, the cross-sectional design cannot explain causal relationships. Prospective studies are recommended to establish causal relationships between psychological distress and other factors. Second, self-reported questionnaires may have led to recall bias. Therefore, the findings of this survey may only provide a descriptive depiction of the present circumstances. Finally, the participants in this study were limited to Zhejiang province, with inherent limitations on their generalizability in China, much less in other countries with different cultures.

In summary, the social isolation of older adults with pre-frailty significantly affects their psychological distress, and the level of health literacy serves as a significant factor between social isolation and psychological distress. This study emphasizes that older persons might avoid psychological distress by improving health literacy to reduce social isolation. Therefore, it is imperative to focus on developing intervention programs to foster social connection as well as health literacy in the future for pre-frail older persons with psychological distress.

| 1. | Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabei R, Cesari M, Chumlea WC, Doehner W, Evans J, Fried LP, Guralnik JM, Katz PR, Malmstrom TK, McCarter RJ, Gutierrez Robledo LM, Rockwood K, von Haehling S, Vandewoude MF, Walston J. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:392-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2058] [Cited by in RCA: 2742] [Article Influence: 228.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Ofori-Asenso R, Lee Chin K, Mazidi M, Zomer E, Ilomaki J, Ademi Z, Bell JS, Liew D. Natural Regression of Frailty Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gerontologist. 2020;60:e286-e298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gené Huguet L, Navarro González M, Kostov B, Ortega Carmona M, Colungo Francia C, Carpallo Nieto M, Hervás Docón A, Vilarrasa Sauquet R, García Prado R, Sisó-Almirall A. Pre Frail 80: Multifactorial Intervention to Prevent Progression of Pre-Frailty to Frailty in the Elderly. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22:1266-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | First MB. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, and clinical utility. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201:727-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu X, Chen T, Chen S, Yatsugi H, Chu T, Kishimoto H. The Relationship between Psychological Distress and Physical Frailty in Japanese Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Frailty Aging. 2023;12:43-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Uno C, Okada K, Matsushita E, Satake S, Kuzuya M. Friendship-related social isolation is a potential risk factor for the transition from robust to prefrailty among healthy older adults: a 1-year follow-up study. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12:285-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shimada H, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, Makino K, Harada K, Tomida K, Morikawa M, Arai H. Combined impact of physical frailty and social isolation on use of long-term care insurance in Japan: A longitudinal observational study. Maturitas. 2024;182:107921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miura KW, Sekiguchi T, Otake-Matsuura M. The association between mental status, personality traits, and discrepancy in social isolation and perceived loneliness among community dwellers. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:2497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Lima ACP, Maximiano-Barreto MA, Martins TCR, Luchesi BM. Factors associated with poor health literacy in older adults: A systematic review. Geriatr Nurs. 2024;55:242-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gutierrez I, Bryan J, Baquero E, Safford MM. The association between social functioning and health literacy among rural Southeastern African Americans with hypertension. Health Promot Int. 2023;38:daad023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Christiansen J, Lasgaard M, Pedersen SS, Pedersen MH, Friis K. Social Disconnectedness in Individuals with Cardiovascular Disease: Associations with Health Literacy and Treatment Burden. Int J Behav Med. 2024;31:363-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Qi X, Zhang W, Wang K, Pei Y, Wu B. Social isolation and psychological well-being among older Chinese Americans: Does resilience mediate the association? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Huang CH, Lai YC, Lee YC, Teong XT, Kuzuya M, Kuo KM. Impact of Health Literacy on Frailty among Community-Dwelling Seniors. J Clin Med. 2018;7:481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15:259-267. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2278] [Cited by in RCA: 2316] [Article Influence: 92.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chesser AK, Keene Woods N, Smothers K, Rogers N. Health Literacy and Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2016;2:2333721416630492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Guo K, Ouyang J, Minhat HS. The mediating role of health literacy between the presence of chronic disease and psychological distress among older persons in Xi'an city of China. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:2530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Haeri-Mehrizi A, Mohammadi S, Rafifar S, Sadighi J, Kermani RM, Rostami R, Hashemi A, Tavousi M, Montazeri A. Health literacy and mental health: a national cross-sectional inquiry. Sci Rep. 2024;14:13639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Biesecker B, Austin J, Caleshu C. Theories for Psychotherapeutic Genetic Counseling: Fuzzy Trace Theory and Cognitive Behavior Theory. J Genet Couns. 2017;26:322-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Abellan van Kan G, Rolland Y, Bergman H, Morley JE, Kritchevsky SB, Vellas B. The I.A.N.A Task Force on frailty assessment of older people in clinical practice. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12:29-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 717] [Cited by in RCA: 738] [Article Influence: 43.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hoyle RH, Gottfredson NC. Sample Size Considerations in Prevention Research Applications of Multilevel Modeling and Structural Equation Modeling. Prev Sci. 2015;16:987-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, Iliffe S, von Renteln Kruse W, Beck JC, Stuck AE. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist. 2006;46:503-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 849] [Cited by in RCA: 1239] [Article Influence: 65.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chang Q, Sha F, Chan CH, Yip PSF. Validation of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale ("LSNS-6") and its associations with suicidality among older adults in China. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Duong TV, Aringazina A, Kayupova G, Nurjanah, Pham TV, Pham KM, Truong TQ, Nguyen KT, Oo WM, Su TT, Majid HA, Sørensen K, Lin IF, Chang Y, Yang SH, Chang PWS. Development and Validation of a New Short-Form Health Literacy Instrument (HLS-SF12) for the General Public in Six Asian Countries. Health Lit Res Pract. 2019;3:e91-e102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sun X, Lv K, Wang F, Ge P, Niu Y, Yu W, Sun X, Ming WK, He M, Wu Y. Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the Health Literacy Scale Short-Form in the Chinese population. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhou CC, Chu J, Wang T, Peng QQ, He JJ, Zheng WG, Liu DM, Wang XZ, Ma HF, Xu LZ. [Reliability and validity of 10-item Kessler scale (K10) Chinese version in evaluation of mental health status of Chinese population]. Zhongguo Linchuang Xinlixue Zazhi. 2008;16:627-629. |

| 26. | Anderson TM, Sunderland M, Andrews G, Titov N, Dear BF, Sachdev PS. The 10-item Kessler psychological distress scale (K10) as a screening instrument in older individuals. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:596-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Vasiliadis HM, Chudzinski V, Gontijo-Guerra S, Préville M. Screening instruments for a population of older adults: The 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) and the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7). Psychiatry Res. 2015;228:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ye B, Gao J, Fu H. Associations between lifestyle, physical and social environments and frailty among Chinese older people: a multilevel analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Jing Z, Li J, Wang Y, Ding L, Tang X, Feng Y, Zhou C. The mediating effect of psychological distress on cognitive function and physical frailty among the elderly: Evidence from rural Shandong, China. J Affect Disord. 2020;268:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bai Y, Chen Y, Tian M, Gao J, Song Y, Zhang X, Yin H, Xu G. The Relationship Between Social Isolation and Cognitive Frailty Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Depressive Symptoms. Clin Interv Aging. 2024;19:1079-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Taylor HO, Taylor RJ, Nguyen AW, Chatters L. Social Isolation, Depression, and Psychological Distress Among Older Adults. J Aging Health. 2018;30:229-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Park J, Jang Y, Oh H, Chi I. Loneliness as a Mediator in the Association Between Social Isolation and Psychological Distress: A Cross-Sectional Study With Older Korean Immigrants in the United States. Res Aging. 2023;45:438-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |