Published online Aug 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i8.1233

Revised: July 2, 2024

Accepted: July 8, 2024

Published online: August 19, 2024

Processing time: 74 Days and 21.1 Hours

Post-burn anxiety and depression affect considerably the quality of life and recovery of patients; however, limited research has demonstrated risk factors associated with the development of these conditions.

To predict the risk of developing post-burn anxiety and depression in patients with non-mild burns using a nomogram model.

We enrolled 675 patients with burns who were admitted to The Second Affiliated Hospital, Hengyang Medical School, University of South China between January 2019 and January 2023 and met the inclusion criteria. These patients were randomly divided into development (n = 450) and validation (n = 225) sets in a 2:1 ratio. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify the risk factors associated with post-burn anxiety and depression dia

Female sex, age < 33 years, unmarried status, burn area ≥ 30%, and burns on the head, face, and neck were independent risk factors for developing post-burn anxiety and depression in patients with non-mild burns. The nomogram model demonstrated predictive accuracies of 0.937 and 0.984 for anxiety and 0.884 and 0.923 for depression in the development and validation sets, respectively, and good predictive per

The nomogram model predicted the risk of post-burn anxiety and depression in patients with non-mild burns, facilitating the early identification of high-risk patients for intervention and treatment.

Core Tip: This is a retrospective study to predict the risk of developing post-burn anxiety and depression in patients with non-mild burns using a nomogram model. The model was constructed using data from 675 patients with non-mild burns who were classified into development and validation sets in a 2:1 ratio. The nomogram model accurately predicted the risk of post-burn anxiety and depression in these patients, facilitating early identification of and intervention in high-risk individuals.

- Citation: Chen J, Zhang JF, Xiao X, Tang YJ, Huang HJ, Xi WW, Liu LN, Shen ZZ, Tan JH, Yang F. Nomogram for predicting the risk of anxiety and depression in patients with non-mild burns. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(8): 1233-1243

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i8/1233.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i8.1233

Burns are a common but serious type of trauma and a cause of substantial health issues globally[1]. According to the World Health Organization, millions of people die or become disabled each year because of burns; most burns occur in children and young adults in low- and middle-income countries[2]. Burns not only cause severe physical harm but also lead to serious psychological distress, including anxiety and depression[3,4]. With advancements in treatment techniques, the survival rate of patients with burns has increased; however, management of post-treatment psychological distress remains challenging. Anxiety and depression are common psychological issues and patients with burns are more sus

Nomograms have been widely used as a novel method to quantify the risk of outcomes by accurately combining and depicting important factors. However, there are limited direct nomogram diagnostic methods for post-burn psychological disorders. In this study, we aimed to predict the risk of anxiety and depression in patients with non-mild burns by establishing a nomogram model.

Between January 2019 and January 2023, patients with burns treated at The Second Affiliated Hospital, Hengyang Medical School, University of South China were selected. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Patients diagnosed with second-degree burns with a total body surface area (TBSA) > 10% or third-degree burns during the period; age ≥ 16 years; consent to participate in the research; hospitalization duration > 7 days; and discharged from the hospital for at least 3 months. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Burn area < 10%; hospitalization duration < 7 days; cognitive impairment; abnormal mental status; or altered consciousness.

The nine-point method[9] was used to calculate the TBSA affected by burns. The head and neck account for 9% of TBSA, the upper limbs for 18%, trunk and perineum for 27%, and the lower limbs for 46% (5 × 9% + 1%), including the buttocks (5% for men and 6% for women), thighs (21%), lower legs (13%), and feet (7% for men and 6% for women). In clinical practice, areas with a TBSA < 1% are usually rounded up to 1%.

Burn severity was classified as follows: Burns with TBSA < 9%, with TBSA between 10% and 29% or third-degree burns with TBSA < 10%, with TBSA between 30% and 49% or third-degree burns with TBSA between 10% and 19%, and with TBSA > 50% or third-degree burns with TBSA > 20% were considered mild, moderate, severe, and critical, respectively. Patients with burns involving < 30% of TBSA, along with shock, altered consciousness, poisoning, or moderate to severe respiratory tract injuries were diagnosed with severe burns[10].

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale was used to assess anxiety and depression[11]. The scale consists of two parts, each with seven questions: Anxiety: Items 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13; and depression: Items 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14. The scores range from 0 to 3 per question, with the total scores categorized as negative (0-7), suspected symptoms (8-10), and positive (11-21)[12]. An alternative scoring method considers a score of 8 as the cut-off, with scores < 8 and > 8 classified as negative and suspected or positive symptoms, respectively[13].

Information extracted from the electronic medical records included demographic data (such as sex, age, and marital status) and clinical data (burn severity, location, classification, TBSA of burns, and causative factors).

Standard deviations and means were calculated for the continuous variables, and median quartile ranges, frequency counts, and percentages, for the categorical variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous variables, whereas the χ2 d or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Variables with a P value < 0.1 in univariate logistic regression were included in the final multivariate analysis. The rms package in the R software was used to construct the nomograms based on the results of the multivariable logistic regression. Discriminatory performance was evaluated quantitatively using the C-index, which is an alternative measure of the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC). Model calibration was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, with non-significant values indicating good calibration. Calibration plots were generated to visually assess the agreement between the predicted and actual risks. Internal validation and calibration were performed using 1000 bootstrap resamples. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was conducted to evaluate the clinical utility of the nomograms generated using the rms package. DCA helps quantify the net benefit of predicting postoperative infections in patients. All analyses were conducted using R for Mac 3.6.3 and SPSS for Mac 26.0.

A total of 675 patients with burns met the inclusion criteria. They were randomly divided into two groups as follows: (1) Development set, consisting of 450 patients (anxiety rate, 46.7% and depression rate, 38.9%); and (2) Validation set, consisting of 225 patients (anxiety rate, 40% and depression rate, 42.2%). We observed no significant differences between the groups in terms of sex, age, personal status, income, education, medical settlement, burn area, causes of burns, burn site, hospitalization period, and anxiety or depression rate (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Development set (n = 450) | Validation set (n = 225) | P value |

| Sex | 0.386 | ||

| Male | 305 (67.8) | 145 (64.4) | |

| Female | 145 (32.2) | 80 (35.6) | |

| Age (years) | 0.782 | ||

| < 33 | 265 (58.9) | 135 (60) | |

| ≥ 33 | 185 (41.1) | 90 (40) | |

| Personal status | 0.174 | ||

| Married | 215 (47.8) | 120 (53.3) | |

| Unmarried | 235 (52.2) | 105 (46.7) | |

| Income | 0.582 | ||

| Satisfied | 190 (42.2) | 100 (44.4) | |

| Unsatisfied | 260 (57.8) | 125 (55.6) | |

| Education | 0.368 | ||

| Middle school or lower | 125 (27.8) | 70 (31.1) | |

| Higher than middle school | 325 (72.2) | 155 (68.9) | |

| Medical settlement | 0.740 | ||

| Self-funded | 95 (21.1) | 50 (22.2) | |

| Medical insurance | 355 (78.9) | 175 (77.8) | |

| Burn area | 0.780 | ||

| 11%-29% | 275 (61.1) | 135 (60) | |

| ≥ 30% | 175 (38.9) | 90 (40) | |

| Causes of burns | 0.831 | ||

| Flame burn | 220 (48.9) | 115 (51.1) | |

| Hot liquid burn | 185 (41.1) | 85 (37.8) | |

| Electric burn | 20 (4.4) | 10 (4.4) | |

| Other | 25 (5.6) | 15 (6.7) | |

| Burn site | 0.913 | ||

| Head, face, and neck area | 240 (53.3) | 119 (52.9) | |

| Limbs and trunk area | 210 (46.7) | 106 (47.1) | |

| Hospitalization period | 0.130 | ||

| < 14 | 135 (30) | 55 (24.4) | |

| ≥ 14 | 315 (70) | 170 (75.6) | |

| Anxiety rate | 210 (46.7) | 90 (40) | 0.100 |

| Depression rate | 175 (38.9) | 95 (42.2) | 0.405 |

The cohort of 450 patients in the development set was divided into anxious and non-anxious groups based on the post-healing anxiety status. Univariate analysis suggested no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05) between the groups in terms of income, education, medical settlement, cause of burns, or hospitalization length. However, we observed statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) with regard to sex, age, personal status, burn area, and burn site between the groups. Multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that female sex, age < 33 years, unmarried status, burn area ≥ 30%, and burn site in the head, face, and neck area were independent risk factors for developing post-healing anxiety in patients with non-mild burns (P < 0.05; Table 2).

| Characteristic | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 2.846 (1.515-3.504) | 0.008 | 1.149 (1.013-1.241) | 0.013 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≥ 33 | Reference | Reference | ||

| < 33 | 3.955 (1.275-5.269) | 0.017 | 3.905 (2.588-5.296) | 0.008 |

| Personal status | ||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | ||

| Unmarried | 1.290 (1.094-1.893) | 0.031 | 1.109 (1.014-1.870) | 0.036 |

| Burn area | ||||

| 11%-29% | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥ 30% | 2.500 (1.431-3.150) | 0.010 | 2.006 (1.638-2.399) | 0.005 |

| Burn site | ||||

| Limbs and trunk area | Reference | Reference | ||

| Head, face, and neck area | 2.926 (2.011-3.853) | 0.002 | 3.571 (2.531-4.301) | 0.008 |

| Income | ||||

| Satisfied | Reference | |||

| Unsatisfied | 0.904 (0.308-2.656) | 0.855 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Middle school or lower | Reference | |||

| Higher than middle school | 0.796 (0.254-2.491) | 0.695 | ||

| Medical settlement | ||||

| Self-funded | Reference | |||

| Medical insurance | 0.871 (0.248-3.055) | 0.829 | ||

| Causes of burns | ||||

| Flame burn | Reference | |||

| Hot liquid burn | 1.067 (0.339-3.354) | 0.912 | ||

| Electric burn | 0.667 (0.061-7.254) | 0.739 | ||

| Other | 1.000 (0.081-12.399) | 1.000 | ||

| Hospitalization period (days) | ||||

| < 14 | Reference | |||

| ≥ 14 | 0.818 (0.279-2.402) | 0.715 | ||

The cohort of 450 patients in the development set was divided into depression and non-depression groups based on depression experiences after recovery. Univariate analysis suggested no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05) between the groups in terms of income, education, medical settlement, causes of burns, or hospitalization length. However, statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed regarding sex, age, personal status, burn area, and burn site between the groups. Multivariate logistic regression analysis suggested that female sex, age < 33 years, unmarried status, burn area ≥ 30%, and burn site in the head, face, and neck area were independent risk factors for developing post-recovery depression in patients with non-mild burns (P < 0.05; Table 3).

| Characteristic | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 1.615 (1.278-2.499) | 0.005 | 1.801 (1.132-2.229) | 0.035 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≥ 33 | Reference | Reference | ||

| < 33 | 1.372 (1.164-1.769) | 0.025 | 1.483 (1.280-1.987) | 0.006 |

| Personal status | ||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | ||

| Unmarried | 1.294 (1.003-1.843) | 0.023 | 1.123 (1.020-1.740) | 0.022 |

| Burn area | ||||

| 11%-29% | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥ 30% | 1.562 (1.165-1.896) | < 0.001 | 1.986 (1.537-2.254) | < 0.001 |

| Burn site | ||||

| Limbs and trunk area | Reference | Reference | ||

| Head, face, and neck area | 2.667 (1.224-3.980) | 0.020 | 2.199 (1.399-3.486) | 0.021 |

| Income | ||||

| Satisfied | Reference | |||

| Unsatisfied | 0.887 (0.557-0.997) | 0.578 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Middle school or lower | Reference | |||

| Higher than middle school | 0.579 (0.354-1.457) | 0.897 | ||

| Medical settlement | ||||

| Self-funded | Reference | |||

| Medical insurance | 0.457 (0.257-1.789) | 0.456 | ||

| Causes of burns | ||||

| Flame burn | Reference | |||

| Hot liquid burn | 1.026 (0.789-1.456) | 0.789 | ||

| Electric burn | 0.746 (0.554-1.254) | 0.678 | ||

| Other | 1.000 (0.045-11.245) | 1.000 | ||

| Hospitalization period (days) | ||||

| < 14 | Reference | |||

| ≥ 14 | 0.667 (0.421-0.843) | 0.347 | ||

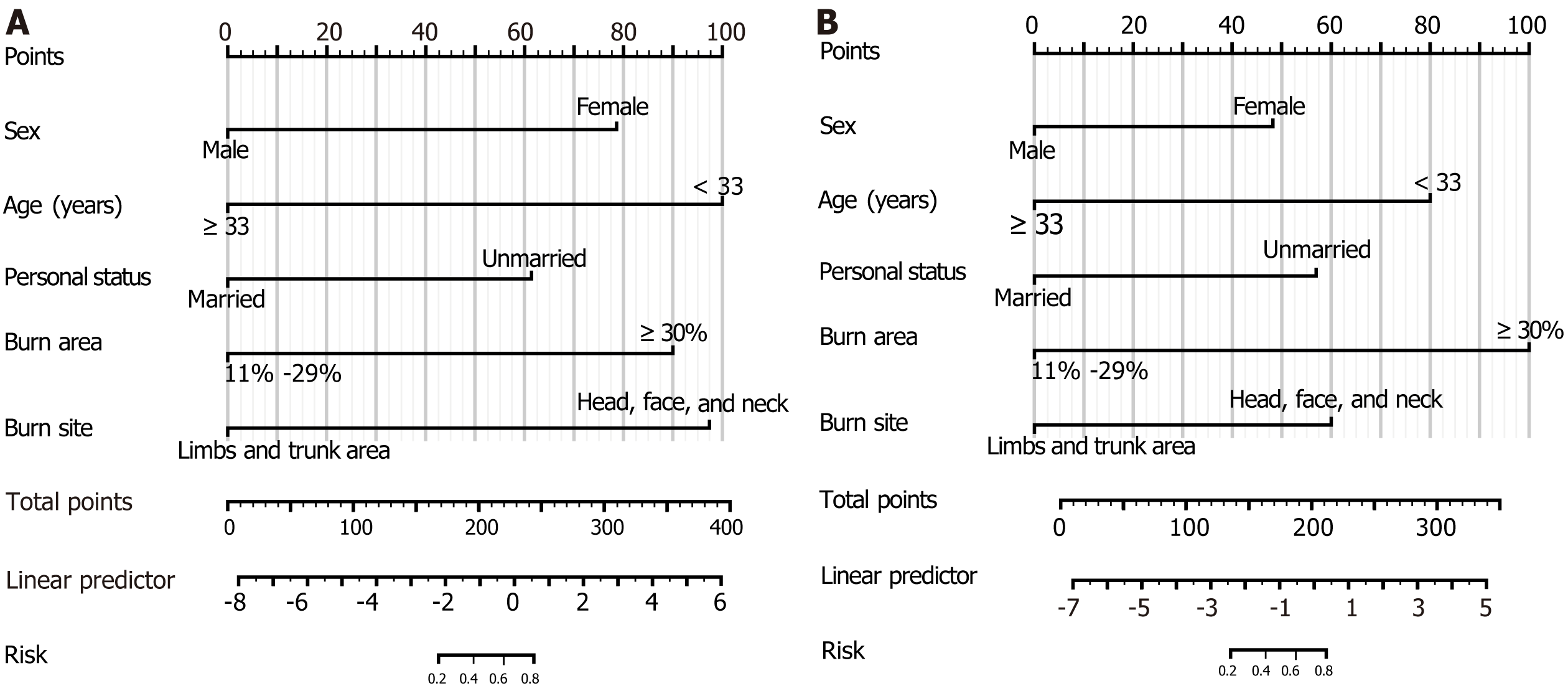

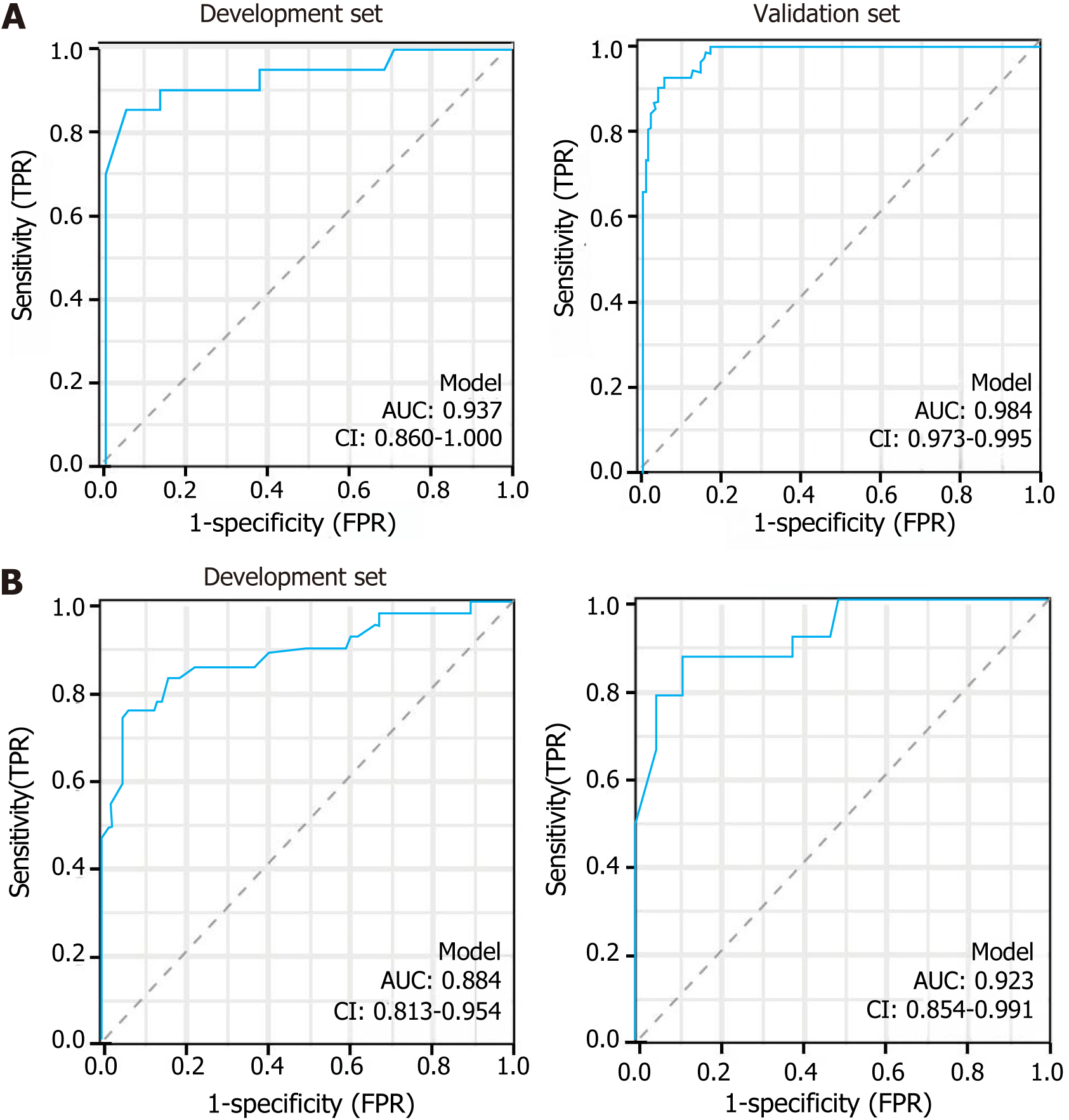

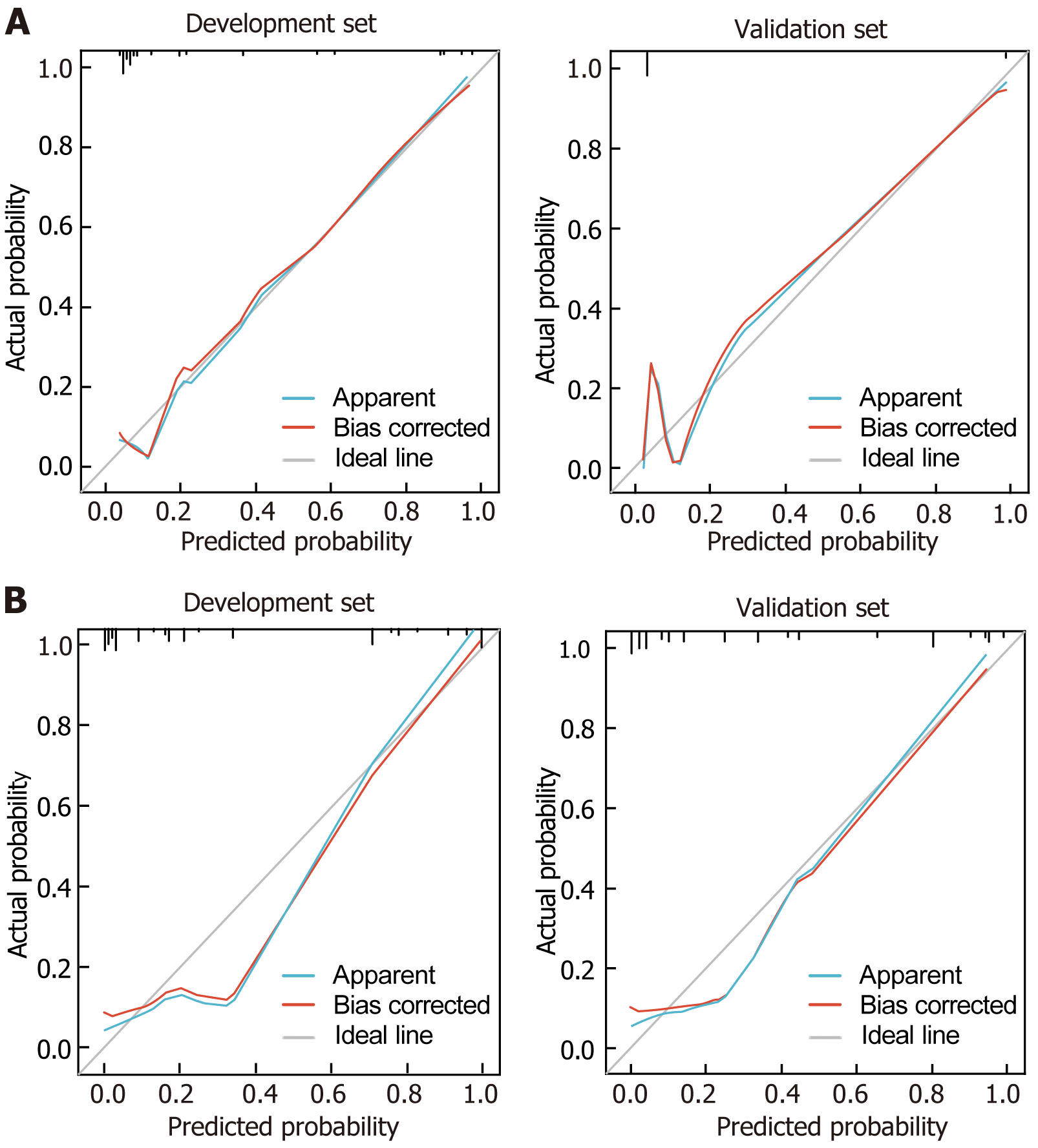

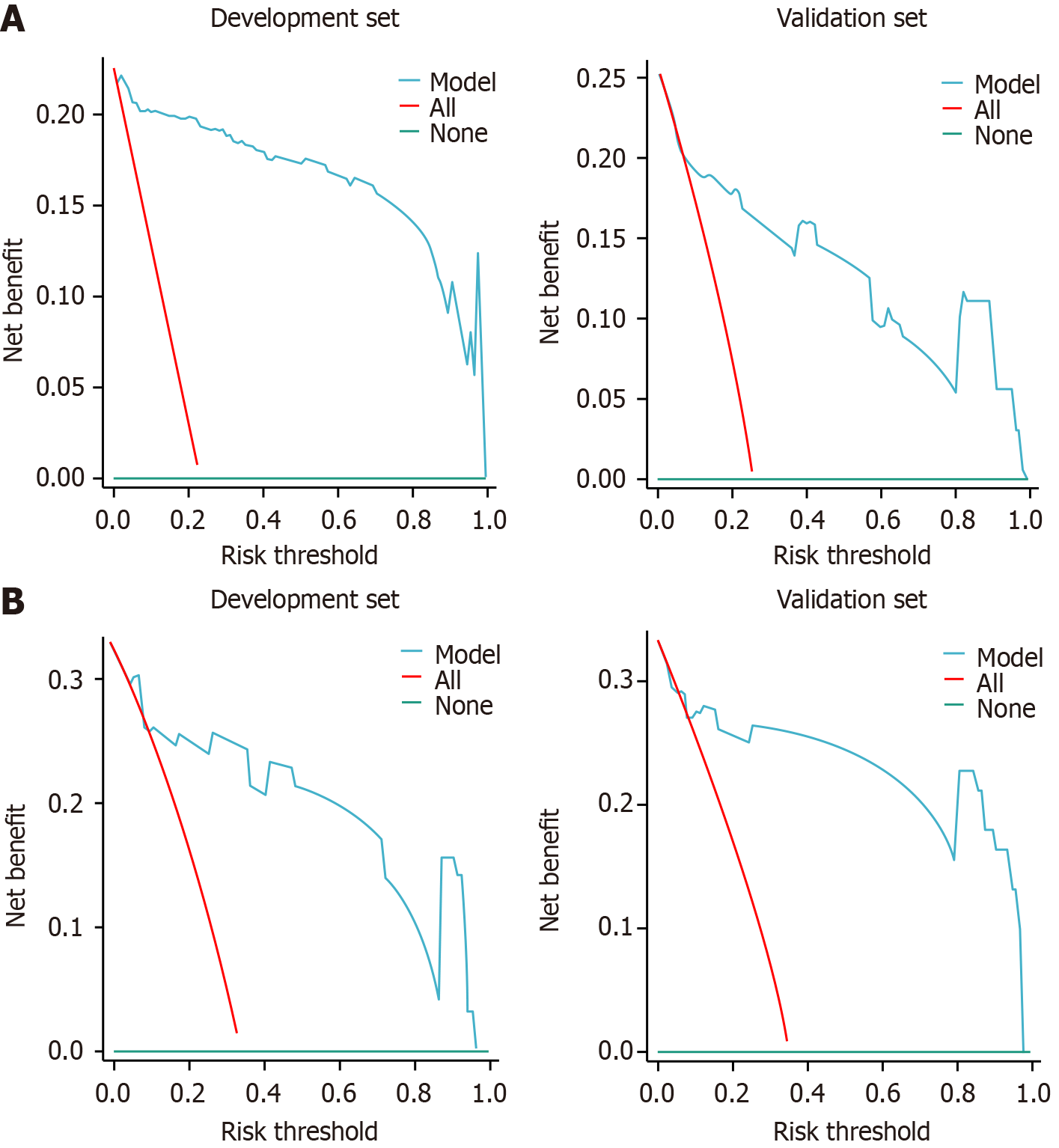

A nomogram was constructed for the prognosis of anxiety and depression based on sex, age, personal status, burn area, and burn site (Figure 1). In the anxiety nomogram, the AUC values for the ROC curve of the development and validation sets were 0.937 and 0.984, respectively (Figure 2A). In the depression nomogram, the AUC values of the development and validation sets were 0.884 and 0.923, respectively (Figure 2B). Calibration curves for anxiety (Figure 3A) and depression (Figure 3B) in the development and validation sets demonstrated good consistency between the predicted and observed rates. Furthermore, DCA indicated that the anxiety (Figure 4A) and depression (Figure 4B) nomograms provided excellent benefits in guiding clinical decisions for both groups.

Burn injury is a common type of trauma; severe burns not only exert a serious impact on physical health but also lead to psychological problems, such as anxiety and depression[14]. Anxiety and depression can significantly affect the quality of life and recovery process in patients[15]. This necessitates accurately predicting the risk of post-burn anxiety and depression in patients with burns. This strategy can help physicians provide timely treatment and improve the patient recovery rate and quality of life. We predicted the risk of post-burn anxiety and depression in patients with non-mild burns by establishing a nomogram model that provides a scientific basis for clinical decision-making.

The anxiety rates of patients with burns in the development and validation sets were 46.7% and 40%, respectively, and the depression rates in the development and validation sets were 38.9% and 42.2%, respectively. Some researchers have explored the prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with burns, but results have been inconsistent. Patients with burns demonstrate high prevalence of anxiety and depression[16,17], consistent with our results; however, psychological problems are rarely reported in these patients[18]. This difference may be attributed to the characteristics of the study population, research methods, and the different regions and time periods. Additionally, differences in the definition criteria and choice of assessment tools for anxiety and depression may have generated varied results. Therefore, for patients with burns from different backgrounds, physicians should consider various factors to assess more accurately the patient mental health status.

In this study, female sex, age < 33 years, unmarried status, burn area ≥ 30%, and burn site in the head, face, and neck area were independent risk factors for developing post-traumatic anxiety and depression, consistent with the literature. Moreover, our findings supported the influence of these factors on anxiety and depression[19,20]. Regarding the role of sex in anxiety, women are more likely to exhibit symptoms during trauma and illness, which may be related to their greater sensitivity and emotional volatility[21]. Additionally, at the physiological level, hormonal changes may make women more prone to anxiety. Women exhibit more prominent anxiety and depression, possibly because of fluctuations in hormonal levels, social role inequalities, and differences in coping mechanisms[22].

Younger patients were more likely to experience anxiety and depression, which may be attributed to increased external pressure and societal expectations faced by younger adults. Patients aged < 33 years may experience greater psychological stress and adaptation difficulties, thereby increasing the risk of anxiety and depression. Age is an important influencing factor, with younger patients being more susceptible to the influence of external environments and events, and this cohort is more likely to exhibit anxiety[23]. Furthermore, young people are uncertain about the future, which may increase their anxiety. Marital status has also been associated with anxiety. Unmarried or single individuals are more likely to experience anxiety during illness and trauma, possibly because of the lack of family and partner support[24]. This phenomenon aligns with our findings because we identified unmarried status as an independent risk factor for experiencing post-traumatic anxiety and depression.

The size of the burn area reflects the extent of damage to the body. Larger burn areas are accompanied by greater pain and physical dysfunction, which increase the likelihood of developing anxiety and depression. In clinical practice, the size of the burn area positively correlates with burn severity. In this study, a larger burn area was associated with a higher incidence of psychological disorders[25]. Burns cause excruciating pain, and the discomfort caused by regular dressing changes, irrigation treatments, and wound itching during the recovery period can lead to discomfort. Additionally, psychological disorders in patients with burns strongly correlate with physiological changes in the nerves, functional tissue structures, and disruption in the endocrine system caused by the treatment[26].

The location of the burn site influences anxiety and depression. People have strong sensory perception in the head, face, and neck; burns in these areas may cause changes in appearance and functional impairment, subsequently affecting psychological state. Facial burns often cause facial alteration or even disfigurement, which severely affects women, leading toward anxiety and depression, an unwillingness to actively communicate, social withdrawal, and possible suicide[27]. Facial burns can severely undermine confidence in women, reduce the possibility of interacting with others, diminish the desire to return to society for work and labor, and make them lose hope for life, thereby causing a series of psychological disorders.

A nomogram was constructed based on female sex, age < 33 years, unmarried status, burn area ≥ 30%, and burn site in the head, face, and neck area to predict post-burn anxiety. For post-burn anxiety, the nomogram demonstrated AUC values of 0.937 and 0.98 in the development and validation sets, respectively. For post-burn depression, it demonstrated AUC values of 0.884 and 0.923 for the development and validation sets, respectively. The calibration and decision curve analyses confirmed the clinical significance and reliability of this nomogram.

During the treatment of burns, patients often face substantial psychosocial stress, which predisposes them to psychological issues such as anxiety and depression. To effectively address these challenges, future research could explore several intervention strategies. First, psychological interventions and support, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, can significantly alleviate psychological stress and assist patients in managing post-traumatic emotions. Second, pharmacological treatments with antidepressants and anxiolytics should be assessed through clinical trials to determine efficacy. Furthermore, the establishment of multidisciplinary teams, comprising psychologists, psychiatrists, burn specialists, nurses, and social workers, is crucial for providing comprehensive support. Additionally, educating patients and their families about mental health can enhance their understanding of and capacity to handle any arising psychological issues. Early intervention and assessment to promptly identify patients in need of psychological intervention can prevent the exacerbation of mental health issues. Regular follow-ups and evaluations are essential to adjust treatment plans and ensure optimal management of mental health conditions. Future studies should also focus on the effectiveness and adaptability of these interventions, exploring personalized treatment strategies based on individual differences.

This study had some limitations. First, only patients from our hospital were included, which may have introduced regional differences, necessitating further research in a broader population to validate the generalizability of our results. Second, the risk factors may not cover all possible factors that influence anxiety and depression levels, and refinement of the model in future studies is expected. Thid, we only statistically explored factors related to anxiety and depression; specific treatment plans to comprehensively consider other factors are required.

We constructed a nomogram to predict the risk of developing post-burn anxiety and depression in patients with non-mild burns and identify the relevant risk factors. Our nomogram model demonstrated good predictive ability and consistency in both development and validation sets as well as high clinical utility.

| 1. | Bhatti DS, Ul Ain N, Zulkiffal R, Al-Nabulsi ZS, Faraz A, Ahmad R. Anxiety and Depression Among Non-Facial Burn Patients at a Tertiary Care Center in Pakistan. Cureus. 2020;12:e11347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nilsson A, Orwelius L, Sveen J, Willebrand M, Ekselius L, Gerdin B, Sjöberg F. Anxiety and depression after burn, not as bad as we think-A nationwide study. Burns. 2019;45:1367-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Farzan R, Hossein-Nezhadi M, Toloei M, Rimaz S, Ezani F, Jafaryparvar Z. Investigation of Anxiety and Depression Predictors in Burn Patients Hospitalized at Velayat Hospital, a Newly Established Burn Center. J Burn Care Res. 2023;44:723-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Markiewitz N, Cox C, Krout K, McColl M, Caffrey JA. Examining the Rates of Anxiety, Depression, and Burnout Among Providers at a Regional Burn Center. J Burn Care Res. 2019;40:39-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ault P, Plaza A, Paratz J. Scar massage for hypertrophic burns scarring-A systematic review. Burns. 2018;44:24-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Turner E, Robinson DM, Roaten K. Psychological Issues. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2023;34:849-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Su YJ. PTSD and depression in adult burn patients three months postburn: The contribution of psychosocial factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2023;82:33-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Barrett LW, Fear VS, Waithman JC, Wood FM, Fear MW. Understanding acute burn injury as a chronic disease. Burns Trauma. 2019;7:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nelson S, Conroy C, Logan D. The biopsychosocial model of pain in the context of pediatric burn injuries. Eur J Pain. 2019;23:421-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rosenberg L, Rosenberg M, Sharp S, Thomas CR, Humphries HF, Holzer CE 3rd, Herndon DN, Meyer WJ 3rd. Does Acute Propranolol Treatment Prevent Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Anxiety, and Depression in Children with Burns? J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28:117-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28548] [Cited by in RCA: 31824] [Article Influence: 757.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Battle DE. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Codas. 2013;25:191-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JM. The Tilburg Frailty Indicator: psychometric properties. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11:344-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 501] [Cited by in RCA: 703] [Article Influence: 46.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zaman NI, Zahra K, Yusuf S, Khan MA. Resilience and psychological distress among burn survivors. Burns. 2023;49:670-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gibson JAG, Dobbs TD, Griffiths R, Song J, Akbari A, Bodger O, Hutchings HA, Lyons RA, John A, Whitaker IS. The association of anxiety disorders and depression with facial scarring: population-based, data linkage, matched cohort analysis of 358 158 patients. BJPsych Open. 2023;9:e212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jiang D, Jiang S, Gong F, Yuan F, Zhao P, He X, Lv G, Chu X. Correlation between Depression, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Inflammatory Factors in Patients with Severe Burn Injury. Am Surg. 2018;84:1350-1354. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Sirancova K, Raudenska J, Zajicek R, Dolezal D, Javurkova A. Psychological Aspects in Early Adjustment After Severe Burn Injury. J Burn Care Res. 2022;43:9-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bonsu K, Kugbey N, Ayanore MA, Atefoe EA. Mediation effects of depression and anxiety on social support and quality of life among caregivers of persons with severe burns injury. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12:772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Khanipour M, Lajevardi L, Taghizadeh G, Azad A, Ghorbani H. The investigation of the effects of occupation-based intervention on anxiety, depression, and sleep quality of subjects with hand and upper extremity burns: A randomized clinical trial. Burns. 2022;48:1645-1652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Thibaut A, Shie VL, Ryan CM, Zafonte R, Ohrtman EA, Schneider JC, Fregni F. A review of burn symptoms and potential novel neural targets for non-invasive brain stimulation for treatment of burn sequelae. Burns. 2021;47:525-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Farzan R, Ghorbani Vajargah P, Mollaei A, Karkhah S, Samidoust P, Takasi P, Falakdami A, Firooz M, Hosseini SJ, Parvizi A, Haddadi S. A systematic review of social support and related factors among burns patients. Int Wound J. 2023;20:3349-3361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cariello AN, Perrin PB, Tyler CM, Pierce BS, Maher KE, Librandi H, Sutter ME, Feldman MJ. Mediational models of pain, mental health, and functioning in individuals with burn injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2021;66:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Woolard A, Hill NTM, McQueen M, Martin L, Milroy H, Wood FM, Bullman I, Lin A. The psychological impact of paediatric burn injuries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:2281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Herrera-Escobar JP, Seshadri AJ, Stanek E, Lu K, Han K, Sanchez S, Kaafarani HMA, Salim A, Levy-Carrick NC, Nehra D. Mental Health Burden After Injury: It's About More than Just Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Ann Surg. 2021;274:e1162-e1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mahendraraj K, Durgan DM, Chamberlain RS. Acute mental disorders and short and long term morbidity in patients with third degree flame burn: A population-based outcome study of 96,451 patients from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database (2001-2011). Burns. 2016;42:1766-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Williams FN, Herndon DN, Suman OE, Lee JO, Norbury WB, Branski LK, Mlcak RP, Jeschke MG. Changes in cardiac physiology after severe burn injury. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32:269-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Atwell K, Bartley C, Cairns B, Charles A. Incidence of self-inflicted burn injury in patients with Major Psychiatric Illness. Burns. 2019;45:615-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |