Published online Jun 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i6.904

Revised: May 8, 2024

Accepted: May 15, 2024

Published online: June 19, 2024

Processing time: 89 Days and 22 Hours

Stroke frequently results in oropharyngeal dysfunction (OD), leading to difficulties in swallowing and eating, as well as triggering negative emotions, malnutrition, and aspiration pneumonia, which can be detrimental to patients. However, routine nursing interventions often fail to address these issues adequately. Systemic and psychological interventions can improve dysphagia symptoms, relieve negative emotions, and improve quality of life. However, there are few clinical reports of systemic interventions combined with psychological interventions for stroke patients with OD.

To explore the effects of combining systemic and psychological interventions in stroke patients with OD.

This retrospective study included 90 stroke patients with OD, admitted to the Second Affiliated Hospital of Qiqihar Medical College (January 2022–December 2023), who were divided into two groups: regular and coalition. Swallowing function grading (using a water swallow test), swallowing function [using the standardized swallowing assessment (SSA)], negative emotions [using the self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) and self-rating depression scale (SDS)], and quality of life (SWAL-QOL) were compared between groups before and after the inter

Post-intervention, the coalition group had a greater number of patients with grade 1 swallowing function compared to the regular group, while the number of patients with grade 5 swallowing function was lower than that in the regular group (P < 0.05). Post-intervention, the SSA, SAS, and SDS scores of both groups decreased, with a more significant decrease observed in the coalition group (P < 0.05). Additionally, the total SWAL-QOL score in both groups increased, with a more significant increase observed in the coalition group (P < 0.05). During the intervention period, the total incidence of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia in the coalition group was lower than that in the control group (4.44% vs 20.00%; P < 0.05).

Systemic intervention combined with psychological intervention can improve dysphagia symptoms, alleviate negative emotions, enhance quality of life, and reduce the incidence of aspiration pneumonia in patients with OD.

Core Tip: Patients with stroke combined with oropharyngeal dysfunction are prone to malnutrition, aspiration pneumonia, and psychological problems for an extended period, which are factors that indirectly contribute to disability and death. Through this investigation, we found that compared with conventional nursing, systemic intervention combined with a psychological intervention can effectively improve patients' swallowing function, relieve patients' anxiety and depression, and improve their quality of life.

- Citation: Song J, Wang JD, Chen D, Chen J, Huang JF, Fang M. Effect of a systemic intervention combined with a psychological intervention in stroke patients with oropharyngeal dysfunction. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(6): 904-912

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i6/904.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i6.904

Stroke is associated with a high rate of disability, and various dysfunctions often remain after onset. Oropharyngeal dysfunction (OD) is the most common complication of stroke[1]. It has been reported that the incidence of OD after stroke is 30%–65%[2]. Although some stroke patients can recover within a few weeks after stroke onset, between 11% and 50% of patients still experience OD after 6 months[3].

From the perspective of modern medicine, OD is believed to be caused by cerebral ischemia and hypoxia, leading to damage to the cortex, cortical bulbar tract, intracranial nerve, and glossopharyngeal nerve, and resulting in the loss of normal innervation of muscle groups and effectors by upper motor neurons[2,4]. The main clinical manifestations include obstruction during swallowing, inability to chew, difficulty in swallowing, coughing, aspiration, and food reflux. If timely intervention is not implemented, patients may develop water and electrolyte disorders, malnutrition, aspiration pneumonia, and severe suffocation directly[5,6]. At the same time, patients often experience psychological disorders such as panic, anxiety, and depression with respect to eating. These psychological issues are not only detrimental to the rehabilitation prognosis of stroke patients, but also increase the case fatality rate[7].

Studies have indicated that early identification of high-risk groups for swallowing disorders and active and effective preventive interventions can improve the clinical symptoms of patients and reduce long-term mortality[8].

Conventional nursing practices often lack individuality, resulting in suboptimal intervention effects in some patients. Systemic intervention is a relatively comprehensive nursing method involving systemic drug treatment and oral training to achieve an effective assessment of disease changes and improve diagnosis and treatment cooperation[9].

Clematis chinensis has the traditional use of dispelling wind dampness and promoting the circulation of channels and collaterals[10]. The "Compendium of Materia Medica" includes the use of Clematis chinensis in the treatment of "bone choking." Stroke patients with dysphagia experience excessive production of phlegm and saliva, discomfort in the pharynx, and obstruction of meridians and collaterals. The symptoms are similar to those of bone lumps. The effects of Clematis chinensis on gastrointestinal qi movement have been extended to the treatment of dysphagia[11].

Oral function training is based on the plasticity and repair ability of the central nervous system. Stimulating the oral intima to input sensory signals to the brainstem and cerebral cortex promotes the formation of new conduction pathways for related sensory-motor neurons and diseased nerve endings and reestablishes a motor reflex arc to promote the closure of the patient's lips and enhance the driving force of the tongue muscle[12]. Researchers have applied this rehabilitation method to older patients with dysphagia and stroke combined with OD, and the approach has been shown to promote their swallowing function and improve their quality of life[13]. Psychological interventions can provide psychological counseling for patients' psychological problems, effectively reduce psychological pressure, improve negative mood, enhance patient compliance and confidence, and improve the effect of clinical interventions. However, there are few clinical reports on the application value of systemic intervention measures such as nebulizing inhalation of Clematis chinensis decoction combined with oral function training and psychological intervention in patients with swallowing disorders after stroke. In this study, we aimed to explore the effect of combining systemic and psychological interventions on the efficacy, negative emotions, and quality of life of stroke patients with OD.

The retrospectively included 90 stroke patients with OD who were admitted from January 2022 and December 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients who met the diagnostic criteria for stroke[14] and dysphagia[15] who were diagnosed with stroke with OD by head computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); and (2) conscious, with normal communication skills. The exclusion criteria comprised the following comorbidities: (1) Immune system disease; (2) malignant tumor; (3) swallowing dysfunction caused by factors other than stroke; (4) serious diseases affecting important organs; (5) mental illness; and (6) critical conditions that precluded evaluation.

Based on differences in the intervention methods, the patients were divided into regular and coalition groups. The coalition group received a combination of systemic and psychological interventions. Each group consisted of 45 patients. There was no significant difference in the general data between the two groups (P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Group | Gender | Age (yr) | Course of disease (d) | Stroke type | ||

| Male | Female | Ischemic | Hemorrhagic | |||

| Coalition group (n = 45) | 26 (57.78) | 19 (42.22) | 61.24 ± 8.97 | 13.11 ± 1.34 | 30 (66.67) | 15 (33.33) |

| Regular group (n = 45) | 24 (53.33) | 21 (46.67) | 62.33 ± 8.97 | 12.96 ± 1.40 | 27 (60.00) | 18 (40.00) |

| χ2/t | 0.180 | -0.576 | 0.540 | 0.431 | ||

| P value | 0.671 | 0.566 | 0.591 | 0.512 | ||

The regular intervention group received routine nursing interventions, which included the following: (1) On the second day after admission, nurses performed a water-swallowing test to evaluate swallowing function; patients with dysphagia were fed a paste diet, and those with grade III dysphagia were fed via a nasogastric tube; (2) diet guidance was provided, including recommendations regarding eating position, paste food deployment, feeding methods, nasal feeding, and other matters; and (3) swallowing training was conducted, involving guiding family members to place their index and middle fingers on the patient's cricoid cartilage and instructing the patient to swallow. The pharynx was stimulated using a cold spoon.

Based on the regular group, the coalition group received systemic intervention measures combined with psychological interventions. The systemic intervention measures were as follows: (1) A traditional Chinese medicine intervention, which consisted of dried slices of Clematis chinensis Osbeck (Beijing Sanhe Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) decocted with 250 mL water for 5 min and then decocted for an additional 20 min. The decoction was prepared into 200 mL samples of Chinese medicine juice (containing 25 g raw Clematis chinensis Osbeck per 100 mL) and stored at 5 °C in the refrigerator. Ten milliliters of Clematis chinensis Osbeck liquid was administered twice daily via atomization until the liquid was depleted; (2) Oral swallowing function training was conducted by swallowing rehabilitation specialist nurses after atomization. These nurses evaluated the swallowing function of patients every day and provided one-to-one swallowing rehabilitation exercise training. The training included the following: lip movement, including lip-smashing, lip-spreading, lip-rounding, and lip muscle strength exercises (instructions consisted of asking the patient to close their lips and relax; instructing the patient to close their lips to forcefully close and pull out a tongue plate, which was alternately performed on the left and right sides, whilst concurrently engaging in confrontation training with the lips); tongue movement, tongue extension, tongue contraction, tongue rolling, tongue tip licking of the upper and lower lips, left and right mouth angle training, and tongue muscle resistance training; mandibular joint training, consisting of opening the mouth to the maximum, then relaxing, and moving the jaw to the left and right sides; tactile stimulation, with fingers, cotton swabs, tongue plate, toothbrush, and other items to stimulate the cheek inside and outside, lips, and the whole tongue to increase the sensitivity of these parts; taste stimulation, with different flavors of fruit juice or vegetable soup (i.e., sour, sweet, bitter, spicy) to improve sensitivity and thereby promote appetite; and pharyngeal cold stimulation, consisting of gently touching the patient's soft palate and tongue root with an ice-cold cotton rod, and then performing empty swallowing training. Once a day, after completing a full training session, patients were encouraged to fully engage in their training; (3) Eating care, during which a swallowing rehabilitation specialist nurse assessed the nutritional status of the patient and calculated the total calories required. The daily intake target was set at a minimum of 80% of this amount, and meals were appropriately allocated. Patients took food into their mouth and adjusted it to a suitable viscosity. Infant rice flour was used to as a thickening paste, as needed[5]. There were three types of food: pudding, egg soup, and syrup. Pudding included thick and mashed meat porridge, vegetable puree, and fruit puree. Egg custard included steamed egg custard, bean flower, and bean curd brain, whereas the syrups included rice soup, juice drinks, and soy milk. For the pudding-like foods, 5 mL samples were tested with the patient, feeding at a slow rate, without speaking to the patient during the feeding process. The amount that constituted a comfortable mouthful was noted, with careful observation to address any choking or coughing by pausing feeding. Patients with nasal feeding were given mixed nutritional support: nutrient solution pumping and a self-made homogenized diet, with strict implementation of nasal feeding nursing points; and (4) Psychological intervention involved establishing a good trusting relationship with patients based on respect, sincerity, and empathy. Family members were asked to cooperate in this process. Through discussions about eating habits, patients’ personalities and psychological characteristics were analyzed, and targeted intervention measures were formulated: patients were guided to engage in positive thinking and positive emotions through explanations and case guidance; patients were inspired to recall happy memories and share moments of happiness, such as their happiest past events and preferred hobbies; and patients were asked to remember three positive things every day and encouraged to include these memories in their rehabilitation exercises. Both groups received continuous intervention for 4 wk.

The following tools were used to assess the patients’ conditions: (1) Swallowing function classification: A water swallowing test[16] was used to evaluate the swallowing function classification of the two groups before and after the intervention. The specific method was as follows: Patients drank 30 mL warm water and their swallowing condition was observed to evaluate the rehabilitation effect. Classification: Level 1 (5 points): Can successfully swallow water once within 5 s; level 2 (4 points): More than one attempt is needed to swallow the water, but there is no choking; level 3 (3 points): Water is swallowed at one time, but there is choking; level 4 (2 points): More than one attempt is needed to swallow the water and there is coughing; level 5 (1 point): Cannot swallow all of the water, and there is frequent coughing; (2) Swallowing function: The standardized swallowing assessment (SSA)[17] was used to evaluate the swallowing function of the two groups before and after the intervention. The examination steps were divided into three parts: Clinical examination, including consciousness, head and torso control, respiration, lip closure, soft palate movement, laryngeal function, pharyngeal reflex, and spontaneous cough, with a total score of 8–23 points; and patients were instructed to swallow 5 mL water three times to observe and evaluate whether there was swallowing movement, repeated swallowing, or wheezing during swallowing (total score: 5–11 points). If no abnormality was observed in the above operation, the patient was instructed to swallow 60 mL of water to evaluate whether they coughed during swallowing and the time required for swallowing (total score: 5–12 points). The total combined score for these three steps was 18–46 points. The swallowing function of patients was inversely proportional to the score; that is, the higher the score, the worse the function; (3) Negative emotions: Anxiety and depression were evaluated before and after the intervention. The former was evaluated using the self-rating anxiety scale (SAS)[18], with a full score and a critical value of 100 points and 50 points, respectively. The latter was assessed using the self-rating depression scale (SDS)[19]. The total possible score was 100 points, and the critical value was set at 53 points. The final score was proportional to the severity of anxiety and depression; (4) Quality of life: The Swallowing-Related Quality of Life questionnaire (SWAL-QOL)[20] was used to evaluate the quality of life of the two groups before and after the intervention. The scale assesses 11 dimensions, including eating, psychology, communication, and sleep, via a total of 44 items, each of which is rated using a five-point Likert scale, with a maximum total score of 220 points. The score is proportional to the quality of life; and (5) Occurrence of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia: Judged by history of aspiration; presence of purulent sputum or significantly increased sputum volume, wet rales, or lung consolidation signs, with body temperature > 38.5 °C. Pulmonary CT examination was used to confirm the occurrence of pneumonia.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS software (version 29.0). Frequency variables are expressed as n (%), and continuous variables are reported as the mean ± SD. Between group differences in these variables were tested using t-tests and χ2 tests, respectively. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Pre-intervention, the coalition and regular groups showed no significant differences across the various baseline variables (P > 0.05). The number of cases of grade 1 swallowing function in the coalition group was higher than that in the regular group, and the number of cases of grade 5 swallowing function was lower in the coalition group than that in the regular group (P < 0.05; Table 2).

| Group | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 | |||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Coalition group (n = 45) | 0 (0.00) | 18 (40.00) | 9 (20.00) | 14 (31.11) | 12 (26.67) | 7 (15.56) | 15 (33.33) | 5 (11.11) | 9 (20.00) | 1 (2.22) |

| Regular group (n = 45) | 0 (0.00) | 8 (17.78) | 10 (22.22) | 11 (24.44) | 11 (24.44) | 10 (22.22) | 16 (35.56) | 9 (20.00) | 8 (17.78) | 7 (15.56) |

| χ2 | - | 5.409 | 0.067 | 0.498 | 0.058 | 0.653 | 0.049 | 1.353 | 0.073 | 4.939 |

| P value | - | 0.020 | 0.796 | 0.480 | 0.809 | 0.419 | 0.824 | 0.245 | 0.788 | 0.026 |

Pre-intervention, the SSA ratings of the coalition and regular groups did not differ significantly (P > 0.05). Post-intervention, the SSA scores in both the coalition and regular groups decreased, and the reduction in the coalition group was significantly larger (P < 0.05; Table 3).

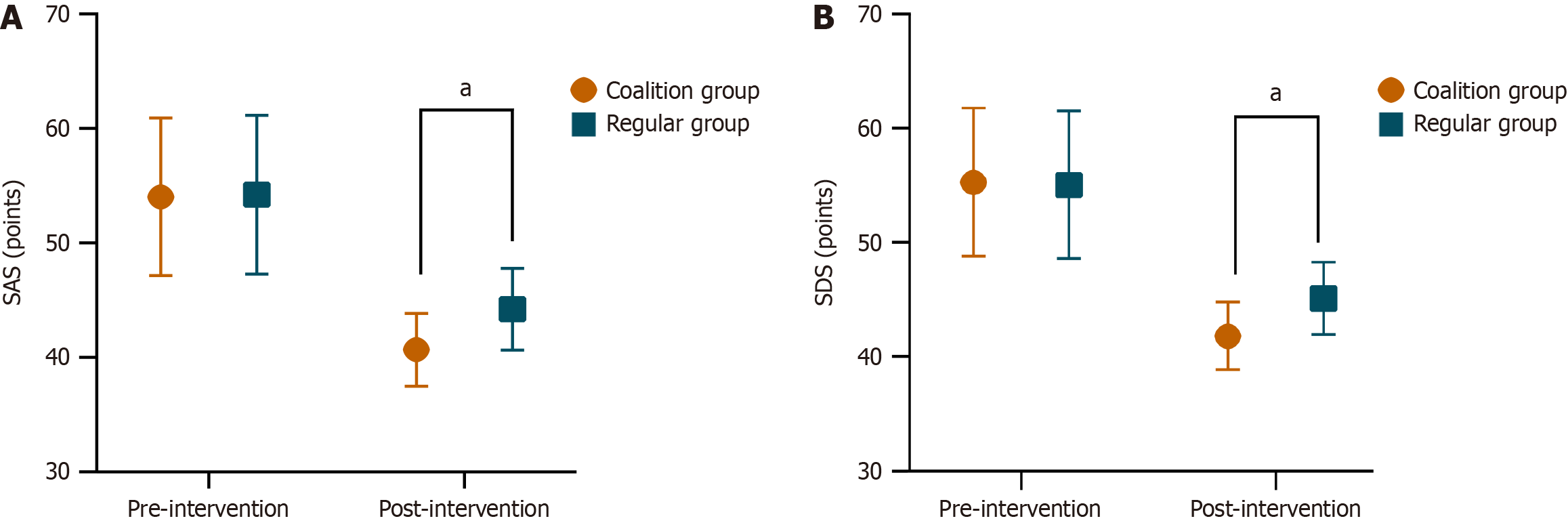

Pre-intervention, the SAS and SDS scores of the coalition group were 54.02 ± 6.88 points and 55.29 ± 6.51 points, respectively, and those of the regular group were 54.22 ± 6.92 points and 55.04 ± 6.46 points, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups (P > 0.05). Post-intervention, the SAS and SDS scores of the coalition group were 40.67 ± 3.18 points and 41.80 ± 2.94 points, respectively, which were lower than those of the regular group at 44.22 ± 3.57 points and 45.09 ± 3.17 points, respectively (P < 0.05; Figure 1).

Pre-intervention, there was no significant difference in the total SWAL-QOL score or the scores of each dimension between the coalition and regular groups (P > 0.05). Post-intervention, the total SWAL-QOL score and the scores of each dimension in the coalition and regular groups increased; however, the increase in the coalition group was larger (P < 0.05; Table 4).

| Group | Pre- and post-intervention | Coalition group (n = 45) | Regular group (n = 45) | t | P value |

| Psychological burden | Pre | 2.29 ± 0.69 | 2.18 ± 0.68 | 0.765 | 0.447 |

| Post | 3.49 ± 0.69d | 2.56 ± 0.78a | 5.972 | < 0.001 | |

| Symptom frequency | Pre | 42.49 ± 10.05 | 40.64 ± 7.52 | 0.986 | 0.327 |

| Post | 49.71 ± 9.12b | 46.13 ± 5.99b | 2.200 | 0.030 | |

| Food choice | Pre | 4.84 ± 1.58 | 4.78 ± 1.24 | 0.223 | 0.824 |

| Post | 6.53 ± 1.22d | 5.78 ± 1.39b | 3.470 | 0.001 | |

| Feeding time | Pre | 4.71 ± 1.32 | 5.16 ± 0.88 | -1.876 | 0.064 |

| Post | 7.09 ± 1.53d | 6.09 ± 1.06c | 3.594 | 0.001 | |

| Willingness to eat | Pre | 4.58 ± 1.12 | 4.49 ± 1.04 | 0.391 | 0.697 |

| Post | 6.80 ± 1.71d | 5.20 ± 1.22a | 5.106 | < 0.001 | |

| Fear | Pre | 9.76 ± 1.80 | 9.67 ± 1.92 | 0.227 | 0.821 |

| Post | 11.49 ± 1.90c | 10.02 ± 1.63 | 3.927 | < 0.001 | |

| Language communication | Pre | 5.49 ± 1.65 | 5.80 ± 1.59 | -0.912 | 0.364 |

| Post | 7.64 ± 1.45d | 6.56 ± 1.27a | 3.790 | < 0.001 | |

| Social function | Pre | 11.71 ± 1.97 | 11.84 ± 1.82 | -0.333 | 0.740 |

| Post | 16.93 ± 2.09d | 12.93 ± 1.97a | 9.334 | < 0.001 | |

| Mental health | Pre | 12.00 ± 1.49 | 11.84 ± 1.61 | 0.475 | 0.636 |

| Post | 16.60 ± 2.49d | 12.49 ± 2.12 | 8.848 | < 0.001 | |

| Fatigued | Pre | 8.13 ± 1.38 | 8.00 ± 1.48 | 0.443 | 0.659 |

| Post | 10.84 ± 1.38d | 8.98 ± 1.27a | 6.674 | < 0.001 | |

| Sleep | Pre | 6.42 ± 1.41 | 6.49 ± 0.94 | -0.264 | 0.792 |

| Post | 8.36 ± 0.96d | 7.00 ± 1.21a | 5.906 | < 0.001 | |

| SWAL-QOL total score | Pre | 112.42 ± 10.61 | 110.89 ± 9.17 | 0.733 | 0.465 |

| Post | 145.49 ± 9.48d | 123.33 ± 7.85d | 12.077 | < 0.001 |

During the intervention period, the total incidence of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia in the coalition group (4.44%) was lower than that in the control group (20.00%; P < 0.05; Table 5).

| Group | Aspiration | Aspiration pneumonia | Total incidence |

| Coalition group (n = 45) | 1 (2.22) | 1 (2.22) | 2 (4.44) |

| Regular group (n = 45) | 5 (11.11) | 4 (8.89) | 9 (20.00) |

| χ2 | 5.057 | ||

| P value | 0.024 |

OD is a common complication of stroke. In such patients, the motor nerves of the mouth muscles, including the tongue, masticatory muscles, and throat muscles, are affected by stroke. Dysphagia occurs after the impairment of muscle motor function. Studies have found that dysphagia can lead to the occurrence of asphyxia and food aspiration in patients[5,21]. Long-term dysphagia can lead to poor nutritional status, increased tension and pessimism, and higher mortality rates among patients[6]. Previously, routine nursing interventions relied solely on swallowing training, and it was often difficult to achieve optimal results. According to recent systemic interventions and reviews, the main rehabilitation goal for dysphagia after stroke is to start directly from the pathological mechanism of swallowing to provide safe swallowing and adequate nutritional intake[22].

From the perspective of traditional Chinese medicine theory, dysphagia syndrome is characterized by phlegm and blood stasis and should be treated using the Jianpi Lishi Huoxue Huayu method[23]. Feng et al[24] showed that Tongyan spray treatment can quickly take effect and improve the clinical symptoms of patients with dysphagia after stroke. Clematis is a member of the Ranunculaceae family. Its rhizome is pungent, salty, and warm. It dispels wind, removes dampness, dredges collaterals, relieves pain, eliminates phlegm and water, and disperses accumulations. It is often used in the treatment of rheumatic arthralgia, limb numbness, tendon and vein contracture, flexion and extension limitations, as well as bone-choking throat[10]. Lee et al[25] found that clematis can enhance the excitability of the smooth muscle of the digestive tract by changing it from rhythmic to peristaltic contractions. Studies have shown that a root decoction of clematis can enhance the esophageal peristalsis rhythm and increase its frequency[26]. Combined with the above modern determination of pharmacological effects of clematis, it is reasonable to assume that clematis is indispensable in the process of improving dysphagia by Tongyan spray. At present, clematis is not widely used in clinical practice, and research on its active ingredients remains relatively superficial. To facilitate broader clinical utilization of clematis, intensified research and development efforts should be directed toward novel clematis-derived pharmaceuticals. Such initiatives would provide a stronger theoretical foundation, enabling more widespread therapeutic application of this plant.

Oral function training is a new swallowing rehabilitation method that can improve the excitability of the central nervous system. The lip muscle training device is placed behind the lip, and the sensory signal is transmitted to the brainstem and cerebral cortex by stimulating the oral intima to promote the formation of new conduction pathways for the related sensory-motor neurons and diseased nerve endings and to re-establish the motor reflex arc to promote the recovery of swallowing function in patients. Oral neuromuscular training stimulates swallowing function in the central nervous system, promotes swallowing-related motor neurons, and promotes the recovery of swallowing function in patients[27]. Hägglund et al[13] showed that oral neuromuscular training not only promotes the rehabilitation of swallowing function in older patients with dysphagia and improves malnutrition but also improves frailty and quality of life. At present, systemic rehabilitation training for patients with swallowing dysfunction can achieve some degree of positive effects; however, many patients in clinical practice have difficulty achieving the desired effect even after systemic rehabilitation treatment. Studies have shown that dysphagia is associated with depression[28]; thus, psychological problems in patients with dysphagia cannot be ignored. A study of rehabilitation nursing for patients with dysphagia showed that a psychological intervention based on routine swallowing therapy could significantly alleviate depression and improve swallowing function[29].

In this study, systemic intervention measures (aerosol inhalation of Clematis chinensis concentrated decoction combined with oral function training) and psychological interventions were applied to stroke patients with swallowing OD. After the intervention, the number of patients with grade 1 swallowing function in the coalition group was greater than that in the regular group, and the number of patients with grade 5 swallowing function was lower than that in the regular group. The SSA, SAS, and SDS scores of the coalition group were lower than those of the regular group. The total SWAL-QOL score and the scores for each dimension were higher in the coalition group than in the regular group. This shows that systemic intervention combined with psychological intervention can effectively improve the symptoms of dysphagia in stroke patients with OD, relieve negative emotions, and improve their quality of life.

The analysis of the pharmacological effects of aerosol inhalation of Clematis chinensis concentrated decoction suggests that it not only provides an effective treatment for use by doctors but also has a beneficial role in family rehabilitation nursing. Effective treatment promotes confidence in stroke patients and their families. At the same time, oral swallowing training can strengthen the coordination of muscles in the face, mouth, and tongue. It can also prevent atrophy of muscle groups related to swallowing movement, improve the flexibility of the swallowing reflex, enhance the swallowing function of patients, and improve their quality of life. In addition, psychological intervention and good nurse–patient trust relationships are integrated to encourage patients to gradually accept and adapt to the pathological state of swallowing dysfunction after stroke to alleviate the abnormal emotions caused by the sudden loss of function. Cooperation of family members helps patients establish confidence in overcoming the disease.

During the intervention period of this study, the total incidence of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia in the coalition group was 4.44%, which was lower than the 20.0% in the control group. These results indicate that systemic interventions combined with psychological interventions can reduce the incidence of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia in patients with stroke complicated by OD. The systemic intervention strengthened the patient's oral care, maintained their oral hygiene, and reduced their SSA score by reducing the aspiration of oral secretions caused by aspiration pneumonia[30]. Psychological intervention, doctor–nurse empathy, one-to-one guidance, and family members' participation in activities can help patients improve their compliance with safe eating, ensure the quality of health education, and reduce the occurrence of dietary accidents.

There are still some limitations to this study. First, the sample size is derived from a single source, and as our study has a retrospective design, it may introduce some selection bias. Second, the traditional Chinese medicine clematis was used for systematic intervention in this study. As the drug is not widely used for OD clinically and no in-depth research has been conducted on its active ingredients, the results may be affected to some extent. Therefore, future studies should focus on prospective, large-sample research and develop clematis-based drugs for further in-depth analysis.

A systemic intervention combined with psychological interventions can effectively improve the symptoms of dysphagia in stroke patients with OD, relieve negative emotions, improve quality of life, and reduce the occurrence of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia.

| 1. | Lu Y, Chen Y, Huang D, Li J. Efficacy of acupuncture for dysphagia after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:3410-3422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Finniss MC, Myers JW, Wilson JR, Wilson VC, Lewis PO. Dysphagia after Stroke: An Unmet Antibiotic Stewardship Opportunity. Dysphagia. 2022;37:260-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Terré R. [Oropharyngeal dysphagia in stroke: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects]. Rev Neurol. 2020;70:444-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Daniels SK, Pathak S, Mukhi SV, Stach CB, Morgan RO, Anderson JA. The Relationship Between Lesion Localization and Dysphagia in Acute Stroke. Dysphagia. 2017;32:777-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Robinson A, Coxon K, McRae J, Calestani M. Family carers' experiences of dysphagia after a stroke: An exploratory study of spouses living in a large metropolitan city. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2022;57:924-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Manabe T, Kotani K, Teraura H, Minami K, Kohro T, Matsumura M. Characteristic Factors of Aspiration Pneumonia to Distinguish from Community-Acquired Pneumonia among Oldest-Old Patients in Primary-Care Settings of Japan. Geriatrics (Basel). 2020;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rofes L, Muriana D, Palomeras E, Vilardell N, Palomera E, Alvarez-Berdugo D, Casado V, Clavé P. Prevalence, risk factors and complications of oropharyngeal dysphagia in stroke patients: A cohort study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;e13338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Maeshima S, Osawa A, Yamane F, Ishihara S, Tanahashi N. Dysphagia following acute thalamic haemorrhage: clinical correlates and outcomes. Eur Neurol. 2014;71:165-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sarfo FS, Ulasavets U, Opare-Sem OK, Ovbiagele B. Tele-Rehabilitation after Stroke: An Updated Systematic Review of the Literature. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27:2306-2318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu LF, Ma XL, Wang YX, Li FW, Li YM, Wan ZQ, Tang QL. Triterpenoid saponins from the roots of Clematis chinensis Osbeck. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2009;11:389-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fu Q, Zan K, Zhao MB, Zhou SX, Shi SP, Jiang Y, Tu PF. Three new triterpene saponins from Clematis chinensis. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2013;15:610-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hägglund P, Hägg M, Wester P, Levring Jäghagen E. Effects of oral neuromuscular training on swallowing dysfunction among older people in intermediate care-a cluster randomised, controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2019;48:533-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hägglund P, Hägg M, Levring Jäghagen E, Larsson B, Wester P. Oral neuromuscular training in patients with dysphagia after stroke: a prospective, randomized, open-label study with blinded evaluators. BMC Neurol. 2020;20:405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, Cockroft KM, Gutierrez J, Lombardi-Hill D, Kamel H, Kernan WN, Kittner SJ, Leira EC, Lennon O, Meschia JF, Nguyen TN, Pollak PM, Santangeli P, Sharrief AZ, Smith SC Jr, Turan TN, Williams LS. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2021;52:e364-e467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 1633] [Article Influence: 408.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bath PM, Lee HS, Everton LF. Swallowing therapy for dysphagia in acute and subacute stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD000323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | DePippo KL, Holas MA, Reding MJ. Validation of the 3-oz water swallow test for aspiration following stroke. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:1259-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Park YH, Han HR, Oh S, Chang H. Validation of the Korean version of the standardized swallowing assessment among nursing home residents. J Gerontol Nurs. 2014;40:26-35; quiz 36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2251] [Cited by in RCA: 2741] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | ZUNG WW. A SELF-RATING DEPRESSION SCALE. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5900] [Cited by in RCA: 6051] [Article Influence: 208.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McHorney CA, Bricker DE, Kramer AE, Rosenbek JC, Robbins J, Chignell KA, Logemann JA, Clarke C. The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: I. Conceptual foundation and item development. Dysphagia. 2000;15:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Boaden E, Burnell J, Hives L, Dey P, Clegg A, Lyons MW, Lightbody CE, Hurley MA, Roddam H, McInnes E, Alexandrov A, Watkins CL. Screening for aspiration risk associated with dysphagia in acute stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;10:CD012679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yang C, Pan Y. Risk factors of dysphagia in patients with ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis and systematic review. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0270096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu J, Wang LN. Neurogenic dysphagia in traditional Chinese medicine. Brain Behav. 2020;10:e01812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Feng XG, Hao WJ, Ding Z, Sui Q, Guo H, Fu J. Clinical study on tongyan spray for post-stroke dysphagia patients: a randomized controlled trial. Chin J Integr Med. 2012;18:345-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee YR, Noh EM, Kwon KB, Lee YS, Chu JP, Kim EJ, Park YS, Kim BS, Kim JS. Radix clematidis extract inhibits UVB-induced MMP expression by suppressing the NF-kappaB pathway in human dermal fibroblasts. Int J Mol Med. 2009;23:679-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Noh EM, Lee YR, Hur H, Kim JS. Radix clematidis extract inhibits TPA-induced MMP-9 expression by suppressing NF-κB activation in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2011;4:879-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kim JH, Kim YA, Lee HJ, Kim KS, Kim ST, Kim TS, Cho YS. Effect of the combination of Mendelsohn maneuver and effortful swallowing on aspiration in patients with dysphagia after stroke. J Phys Ther Sci. 2017;29:1967-1969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kim JY, Lee YW, Kim HS, Lee EH. The mediating and moderating effects of meaning in life on the relationship between depression and quality of life in patients with dysphagia. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:2782-2789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gao J, Zhang HJ. Effects of chin tuck against resistance exercise versus Shaker exercise on dysphagia and psychological state after cerebral infarction. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53:426-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Li L, Huang H, Jia Y, Yu Y, Liu Z, Shi X, Wang F. Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Noninvasive Brain Stimulation on Dysphagia after Stroke. Neural Plast. 2021;2021:3831472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |