Published online May 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i5.742

Revised: March 2, 2024

Accepted: April 3, 2024

Published online: May 19, 2024

Processing time: 153 Days and 13.2 Hours

Despite advances in research on psychopathology and social media use, no comprehensive review has examined published papers on this type of research and considered how it was affected by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak.

To explore the status of research on psychopathology and social media use before and after the COVID-19 outbreak.

We used Bibliometrix (an R software package) to conduct a scientometric analysis of 4588 relevant studies drawn from the Web of Science Core Collection, PubMed, and Scopus databases.

Such research output was scarce before COVID-19, but exploded after the pandemic with the publication of a number of high-impact articles. Key authors and institutions, located primarily in developed countries, maintained their core positions, largely uninfluenced by COVID-19; however, research production and collaboration in developing countries increased significantly after COVID-19. Through the analysis of keywords, we identified commonly used methods in this field, together with specific populations, psychopathological conditions, and clinical treatments. Researchers have devoted increasing attention to gender differences in psychopathological states and linked COVID-19 strongly to depression, with depression detection becoming a new trend. Developments in research on psychopathology and social media use are unbalanced and uncoordinated across countries/regions, and more in-depth clinical studies should be conducted in the future.

After COVID-19, there was an increased level of concern about mental health issues and a changing emphasis on social media use and the impact of public health emergencies.

Core Tip: Rapid changes in the social health environment and the media have seriously affected human mental health. It is therefore important to capture research topics and trends in psychopathology and social media before and after the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic through bibliometrics. The study, which examined 4588 publications from the Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus databases, identified an explosion in the number of findings after the COVID-19 outbreak, whereas such studies had been rare before the pandemic. As researchers increasingly focus on gender differences in psychopathological states and identify strong links between COVID-19 and depression, the detection of depression will become a new trend in the field of psychopathology and social media use.

- Citation: Zhang MD, He RQ, Luo JY, Huang WY, Wei JY, Dai J, Huang H, Yang Z, Kong JL, Chen G. Explosion of research on psychopathology and social media use after COVID-19: A scientometric study. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(5): 742-759

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i5/742.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i5.742

Psychopathology is the study of the occurrence, development, and treatment of mental illnesses. Due to intensified social competition and information overload, psychological stress factors in modern societies have increased significantly, and looser social connections have made people feel alienated. In this context, mental illness is becoming a prominent social problem worldwide. According to United States Census Bureau data, three times as many adults in the United States experienced depression or anxiety in April to May 2020 than in the early stages of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in 2019[1].

Social media refers to interactive platforms based on mobile communication and internet technology. Essentially, social media platforms allow people to create and exchange user-generated content. People search for information, record their lives, express their opinions, and share their emotions on social media platforms, which have become extremely popular due to the development of internet technology. In addition, the use of social media increased significantly due to the social isolation imposed during COVID-19[2]. Many individuals with mental disorders seek help through social media platforms, and social media is increasingly integrated into the professional lives of researchers, transforming many fields of study. Through social media, researchers, including psychopathologists, can conduct peer communication, publicise and communicate professional knowledge to patients in new ways, and employ the abundant information available on social media platforms to identify the opinions, attitudes, and emotions of internet users and detect and intervene in psychological crises[3]. However, the speed and comprehensive coverage of social media can lead to the spread of misinformation. Fake news and conspiracy theories may mislead the public, causing a biased understanding of the pandemic and triggering social panic and chaos. Moreover, the excessive use of social media can cause mental illnesses, such as internet addiction, social anxiety, and negative emotions, such as loneliness and depression[4]. In addition, social media may cause additional harm to people who already have mental illnesses, affecting the treatment of their conditions[5]. Therefore, research on psychopathology and social media holds vital social and academic value.

There have been many valuable achievements in the psychopathology and social media fields. For example, scholars have measured the symptomatologic features of social media overuse, based on the criteria for substance and behavioural addiction provided by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders[6]. Other scholars have discussed the multi-modal hierarchical attention model of depression detection for social media use[7,8]. However, these achievements have been relatively fragmented. Due to rapid changes in the media environment and social norms, it is vital to identify hot research topics and trends in psychopathology and social media via bibliometrics. Bibliometrics - also known as scientometrics - uses mathematical and statistical methods to analyse the elements of academic papers, such as journals, authors, countries, and institutions, to analyse the frequencies and relationships of keywords, and to identify research frontiers and trends in specific fields. Bibliometrics has developed rapidly in recent years. Some scholars have used bibliometrics to explore medical studies on pseudo-information (or misinformation) in social media[9], while others have discussed the bibliometrics of parasitology studies on social media[10]. However, no bibliometric analysis has considered the relationship between psychopathology and social media use. To fill this gap, we analysed relevant English-language literature in the Web of Science Core Collection (WOSCC), PubMed, and Scopus databases to systematically examine current research status and provide valuable references for future researchers investigating psychopathology and social media use. We devoted particular attention to changes in this research field before and after the outbreak of COVID-19, which may provide a reference for researchers considering psychopathology and social media use when future health emergencies arise.

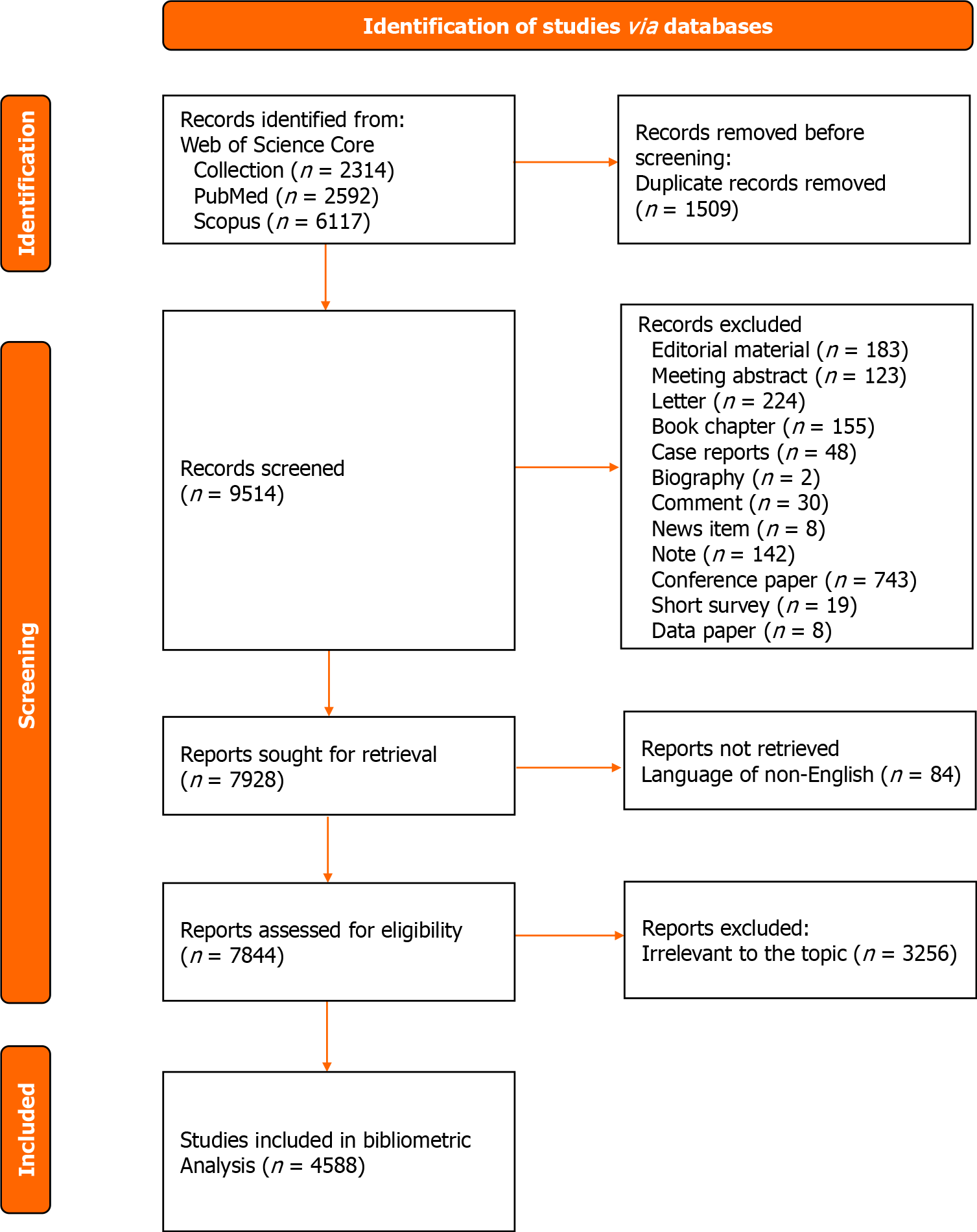

We selected three English-language databases - WOSCC, PubMed, and Scopus - as sources of data up to March 2023 and extracted relevant literature according to the following search formula based on the full texts of articles: (“psychopathology” OR “pathological OR psychology” OR “psychotherapy” OR “anxiety disorders” OR “depression” OR “schizophrenia” OR “phenomenology” OR “Freud” OR “emotional disorders” OR “trait anxiety” OR “perfectionism” OR “Jaspers” OR “psychosis “ OR “mental disorder”) AND (“Weibo” OR “*microblog*” OR “Tencent” OR “Soho” OR “Netease” OR “Twitter” OR “social media” OR “Facebook”). To ensure the accuracy of the results, we based the selection of literature on the double-blind principle, while the title and abstract of each source were separately and manually screened by Zhang MD and He RQ. We excluded duplicate sources and non-academic literature, such as news and newsletters, as well as literature unrelated to the topic and non-English-language literature. If the screening results of the two practitioners did not correspond, Chen G made the final decision regarding inclusion in the study. Finally, the data for this study were provided by 4588 publications (Figure 1). We exported the relevant information (e.g., title, author, keywords, organization, etc.) from each paper into BibTeX format for further analysis.

We used Bibliometrix to obtain relevant statistics for this study. This is a commonly used open-source bibliometric toolkit developed by Aria and Cuccurullo, based on the R platform. The statistical analysis of the element and quantitative characteristics of the literature enabled us to directly and flexibly describe the status and development trends of research on psychopathology and social media use[11-14]. We employed Bibliometrix to display the volume of publications; analyse the impact of journals and authors, demonstrate how institutions, countries, and authors collaborated in the studies, evaluate the core papers, and analyse keyword characteristics.

We used the h-index, g-index, m-index, and total citation (TC) and impact factor (IF) indices to determine the influence of authors and journals. The h-index indicates the number of times a scholar’s paper has been cited by other scholars. The g-index ranks papers from the highest to the lowest numbers of citations and determines whether the total number of citations of the first g papers is greater than or equal to g2. The g-index combines the h and TC indices for each paper, which can prevent certain papers with strong academic influence from being missed. The m-index is calculated according to the following formula: h-index for authors/number of years since the first publication. The m-index enables authors with different career lengths to be compared[15].

We conducted a collaboration network analysis by identifying the authors, institutions, and countries that appeared in the same papers. In a collaboration network, the larger the node, the more frequently the element appears in the network, and the thickness of the connection line represents the intensity of cooperation. For example, if a paper has two or more authors, there will be a link between these authors in the collaboration network. Different colours in the network represent diverse research groups or communities.

After the core papers on psychopathology and social media use were evaluated, we introduced TCs as a factor. The number of times other researchers had cited a paper indicated the potentially higher quality and value of the paper. Papers with high TCs are likely to stimulate new ideas and directions of research cooperation, and they may play an important role in promoting scientific research innovation or providing basic knowledge of certain research fields.

Relevant analysis based on keywords is the most important element of bibliometric research, and it enabled us to identify hot research topics in the fields of psychopathology and social media use. We conducted an analysis of the hot research topics by combining keyword co-occurrence and co-word analyses.

Keyword co-occurrence indicates the occurrence of two or more keywords in a paper, and co-occurrence analysis can directly demonstrate the correlations between keywords. The size of a node in a co-occurrence plot is proportional to the frequency of its occurrence in the retrieved articles, reflecting the centrality of keywords, and the thickness of the lines between nodes reflects the intensity of keyword associations. Keywords of the same colour belong to a cluster, thus enabling the meaning sets of the interrelated words to be determined by colour.

In a thematic map, the horizontal axis indicates the degree of keywords’ convergence to the centre, while the vertical axis presents the relative densities of keywords. By dividing the axes into four quadrants, the dynamic development of the research can be displayed more intuitively. Motor themes (the themes that are fully developed and have high research value) with high centrality and density are distributed in the top-right quadrant, representing key research areas. Niche themes are distributed in the top-left quadrant and are less strongly related to other themes, but because of their high density, they may be related to other themes over time and become motor themes. The bottom-left quadrant includes emerging or declining themes with low density and low centrality, suggesting that in the field of research, these are emerging topics or topics that are disappearing. The bottom-right quadrant contains the basic themes, which have high centrality but low density. These themes are vitally significant, but not yet fully developed, indicating possible future research trends. In a trend topic map, the line segment represents the high frequency of keywords appearing during a specified period, and the circle size represents the frequency of the occurrence of emerging keywords.

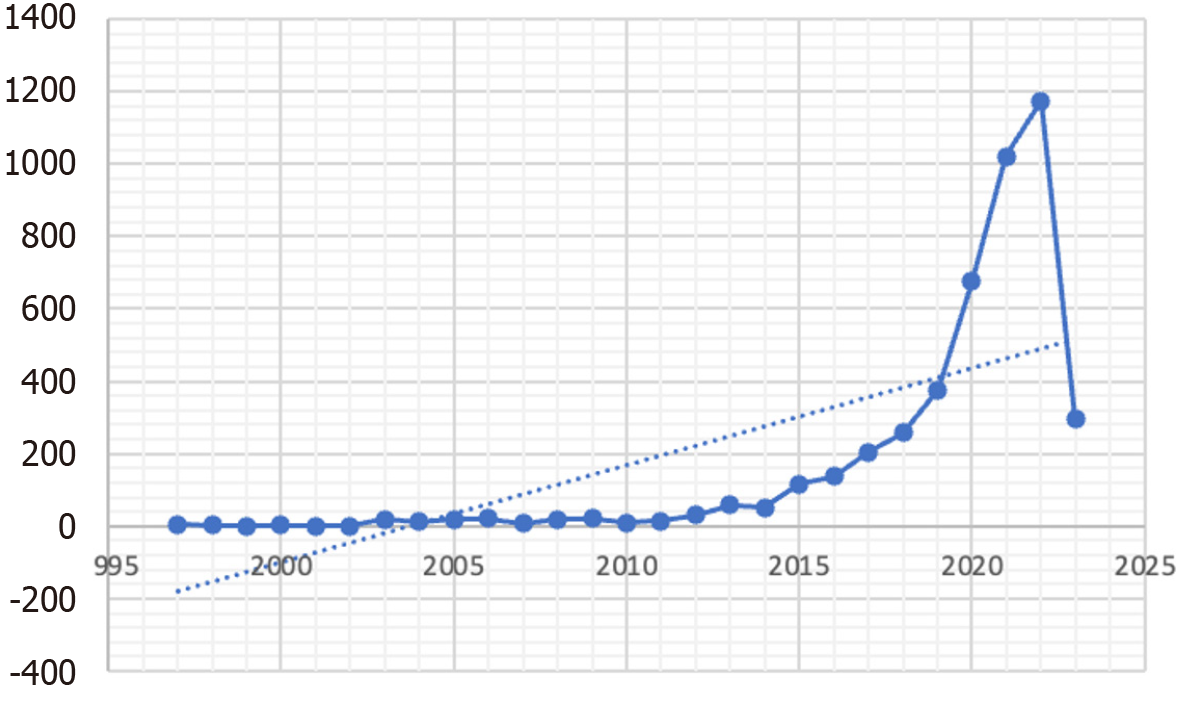

The number of publications in different years reflected the development stages of research in this field (Figure 2). The first stage constituted the years prior to 2015, and the number of relevant papers in this stage was relatively small. The second stage was from 2015 to 2019, when there was a small increase in the number of publications. The third stage was from 2019 to date. The number of relevant published papers increased dramatically following the outbreak of COVID-19, reaching a peak of 1173 publications in 2022. Due to time constraints in relation to data collection, the number of publications listed in 2023 did not reflect the total output for this year. In general, the output of the research on psychopathology and social media use demonstrated annual increases and an explosive increase after the COVID-19 pandemic.

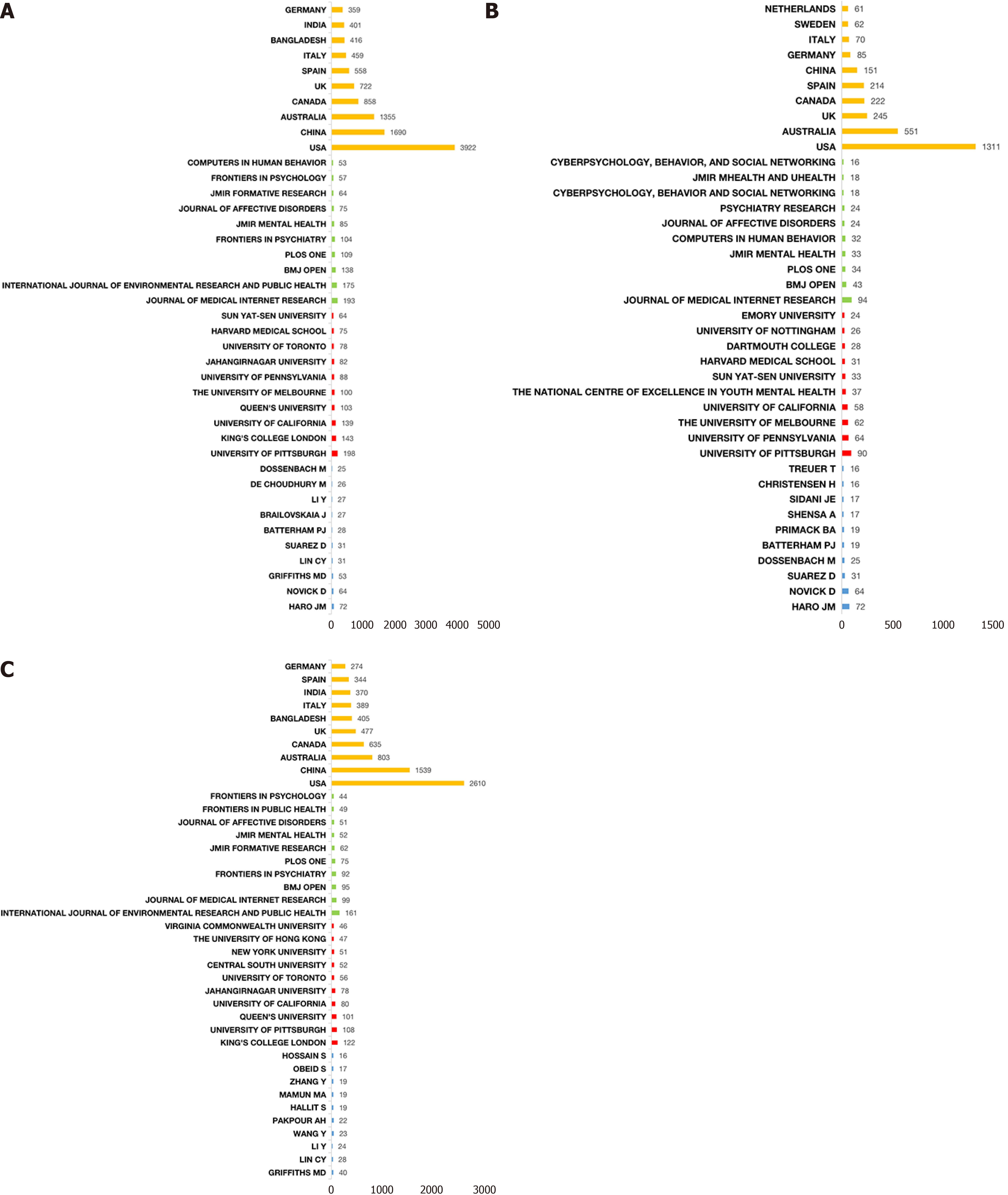

Figure 3 presents the numerical rankings of the papers published by different countries, journals, institutions, and authors. The overall situation and the situations before and after the COVID-19 outbreak are presented in Figure 3A-C, respectively. In terms of journals, the Journal of Medical Internet Research published the most papers (193 papers, 4.2%), followed by the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (175 papers, 3.8%), and BMJ OPEN (138 papers, 3%). The top 10 journals collectively published more than one-fifth of the total number of papers, and most of the listed journals were located in the Journal Citation Reports edition 2023 (JCR) ranking quartiles I or II. Regarding institutions, high-yielding institutions were located in North America, Europe, and Oceania. A few high-yielding institutions were located in Asia, such as China (Sun Yat-Sen University) and Bangladesh (Jahangirnagar University). Four of the top 10 high-yielding institutions were located in the United States. Regarding authors, Haro JM et al. published the most papers (72 papers), followed by Novick D (64 papers), and Griffiths MD (53 papers). From the perspective of countries, the countries with the highest number of publications were the United States, China, and Australia. A comparison of the publication output before and after COVID-19 revealed that the COVID-19 outbreak played an important role in the yield of scientific research on psychopathology and social media use. The number of studies in China and India significantly increased after COVID-19 due to the high incidence and widespread impact of the pandemic in these countries. In addition, the categories of high-yielding journals also varied; prior to COVID-19, medical and cybertechnical journals were plentiful, but after the pandemic, the number of environmental and social science journals increased significantly.

The results for the h, g, m, TC, and IF indices are presented in Tables 1 and 2. According to the h-index, the most in

| Author | H_index | G_index | M_index | TC | PY_start |

| Haro JM | 22 | 42 | 1.048 | 1804 | 2003 |

| Griffiths MD | 19 | 45 | 2107 | ||

| Novick D | 19 | 37 | 0.905 | 1414 | 2003 |

| Suarez D | 14 | 31 | 0.737 | 988 | 2005 |

| Lin CY | 12 | 27 | 2 | 780 | 2018 |

| Primack BA | 12 | 24 | 1.5 | 1842 | 2016 |

| Shensa A | 11 | 23 | 1.375 | 1811 | 2016 |

| Sidani JE | 11 | 21 | 1.375 | 1809 | 2016 |

| Brailovskaia J | 10 | 22 | 1.25 | 490 | 2016 |

| Escobar-Viera CG | 10 | 25 | 1.429 | 997 | 2017 |

| Journals | H_index | G_index | M_index | TC | IF |

| Journal of Medical Internet Research | 31 | 52 | 2.818 | 3063 | 7.076 |

| Computers in Human Behavior | 25 | 53 | 2.273 | 3174 | 8.957 |

| Plos One | 24 | 62 | 2.182 | 3864 | 3.752 |

| Journal of Affective Disorders | 17 | 58 | 1.545 | 3440 | 6.533 |

| Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking | 16 | 27 | 1.455 | 1234 | 6.135 |

| Frontiers in Psychiatry | 16 | 31 | 1.778 | 1042 | 5.435 |

| International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | 15 | 43 | 1.5 | 1970 | 4.614 |

| BMJ Open | 13 | 26 | 1.444 | 749 | 3.006 |

| JMIR Mental Health | 13 | 34 | 1.444 | 1168 | 6.332 |

| Psychiatry Research | 12 | 34 | 0.706 | 1179 | 2.493 |

Among the high-impact journals covering research on psychopathology and social media use, the Journal of Medical Internet Research had the highest h-index (31), indicating that of the 31 papers with the top TCs in this journal, each paper had been cited at least 31 times. The second- and third-ranked journals according to the h-index were Computers in Human Behavior (25) and Plos One (24). According to the m-index, the above three journals were also the top three. In terms of the g and TC indices, Plos One was the most influential journal in this field. The journal with the highest IF for research on psychopathology and social media was Computers in Human Behavior (8957).

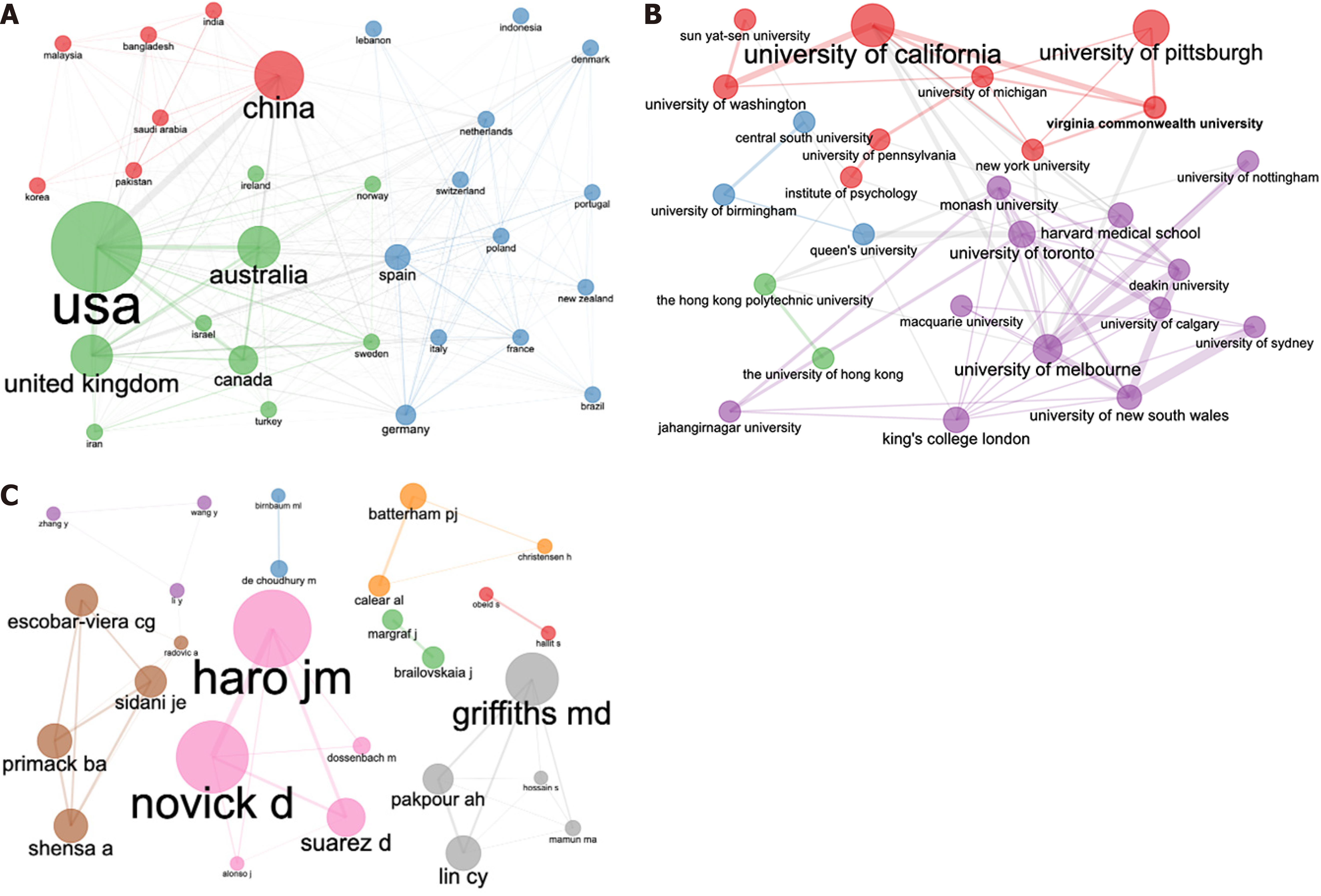

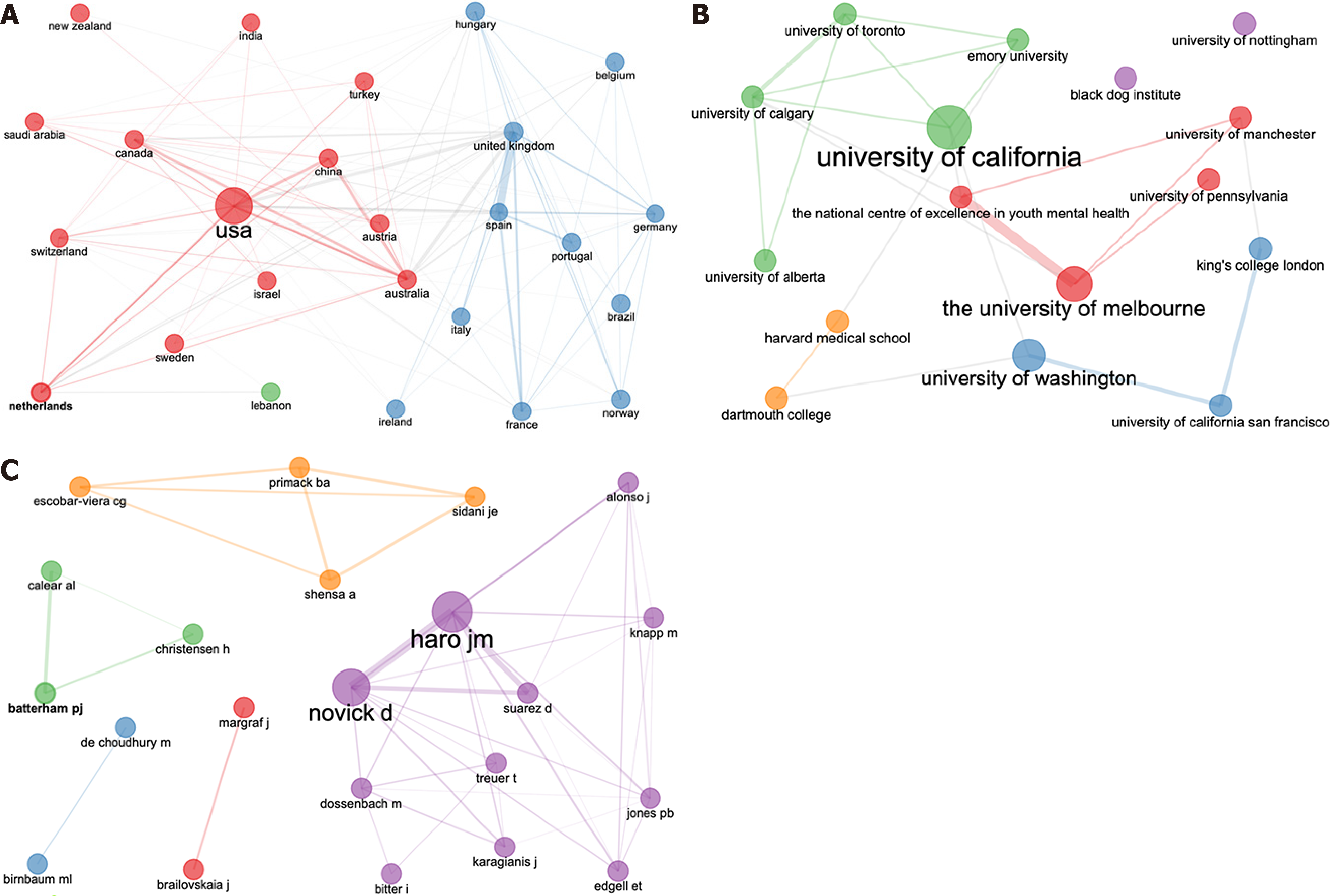

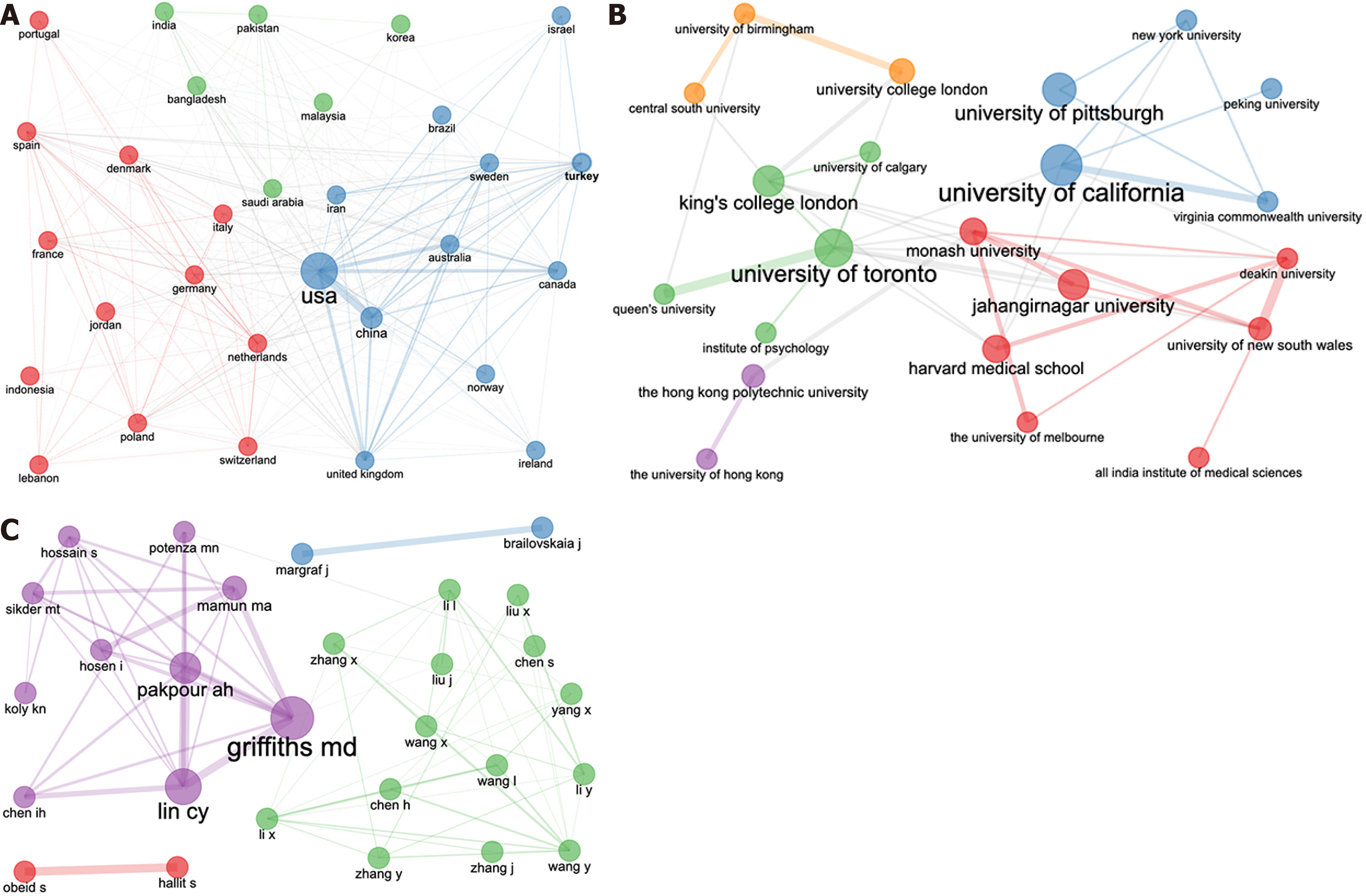

The overall collaboration network is presented in Figure 4. In terms of national collaboration (Figure 4A), there were three groups: A United States-led group (green), including developed countries such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada; a China-led group (red), which included China, Saudi Arabia, India, South Korea, and other Asian countries; and a European group (blue), consisting of countries such as Spain, Germany, Poland, and Denmark. In this national collaboration network, the United States had the largest node and the most complex links with other countries, holding the global core position in research on psychopathology and social media use.

In terms of institutional collaboration (Figure 4B), there were clear collaboration networks between neighbouring institutions, especially regarding intercountry collaboration. For example, the University of California, the University of Pittsburgh, the University of Washington, the University of Michigan, and other United States institutions formed relatively strong collaboration networks. International collaboration was dominated by institutions in developed countries, which occupied larger areas and had larger nodes in the collaboration network.

An analysis of author collaboration revealed different colours of collaboration networks (Figure 4C), and we observed the formation of an independent network consisting of high-yielding teams, including researchers such as Haro JM and Novick D, who worked closely together.

Next, we evaluated the differences in collaboration networks before and after COVID-19. After COVID-19, the number of institutions and authors in the network increased significantly, and the network structure became more complex. Moreover, international collaboration became more evident after COVID-19. While Lebanon and South Africa had no collaboration with the other countries before COVID-19 (Figure 5A), they collaborated extensively with other countries after the pandemic (Figure 6A). The United States maintained its core position, uninfluenced by COVID-19 (Figures 5A and 6A). Institutional collaboration in the pre-COVID-19 period was concentrated primarily in developed countries; however, collaboration after COVID-19 revealed an increased involvement of institutions in developing countries, such as Jahangirnagar University in Bangladesh and the University of Hong Kong and Hong Kong Polytechnic University in China (Figures 5B and 6B). A number of new scholars and research groups also emerged after COVID-19, including Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH, and Lin CY (Figures 5C and 6C).

The top 10 cited papers are presented in Table 3. Regarding time, although psychopathology and social media use had been studied since the end of the twentieth century, the top 10 cited papers were published after 2010, and 4 of them were published after the COVID-19 outbreak. Regarding research methods, traditional meta-analyses (papers 1 and 5)[16,17], cross-sectional studies (papers 2 and 9)[18,19], and experimental study (paper 2)[19] were used in these most frequently cited papers to explore correlations between social media use and negative psychological states. A small number of studies also used online ecological recognition based on machine-learning predictive models (paper 7)[20] and other advanced methods. The research subjects focused primarily on COVID-19 (papers 1, 4, 5, and 7)[16,17,20,21] and adolescents (papers 3 and 10)[22,23] , which reflected hot research topics in this field. The most frequently cited article in any field has extremely high academic value, and we found that among the top 10 papers in this study, the most frequently cited paper was paper 1: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review, published in 2020. This paper presented a systematic review of the mental health hazards of COVID-19, and it was cited a total of 2095 times.

| Ref. | Paper | DOI | TCs | TC per year | Normalized TC | |

| 1 | Xiong et al[17], 2020 | J Affect Disorders | 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001 | 2095 | 523.75 | 84.06 |

| 2 | Kramer et al[19], 2014 | P Natl Acad Sci USA | 10.1073/pnas.1320040111 | 1383 | 138.30 | 20.84 |

| 3 | O'Keeffe et al[22], 2011 | Pediatrics | 10.1542/peds.2011-0054 | 1022 | 78.62 | 6.34 |

| 4 | Gao et al[21], 2020 | Plos One | 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 | 897 | 224.25 | 35.99 |

| 5 | Dubey et al[16], 2020 | Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev | 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035 | 876 | 219.00 | 35.15 |

| 6 | O'Keeffe et al[22], 2011 | Pediatrics | 10.1542/peds.2011-0054 | 834 | 64.15 | 5.18 |

| 7 | Li et al[20], 2020 | Int J Env Res Pub HE | 10.3390/ijerph17062032 | 824 | 206.00 | 33.06 |

| 8 | Kross et al[55], 2013 | Plos One | 10.1371/journal.pone.0069841 | 696 | 63.27 | 12.24 |

| 9 | Schou Andreassen et al[18], 2016 | Psychol Addict Behav | 10.1037/adb0000160 | 685 | 85.63 | 17.38 |

| 10 | Woods et al[23], 2016 | J Adolesc | 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.008 | 534 | 66.75 | 13.55 |

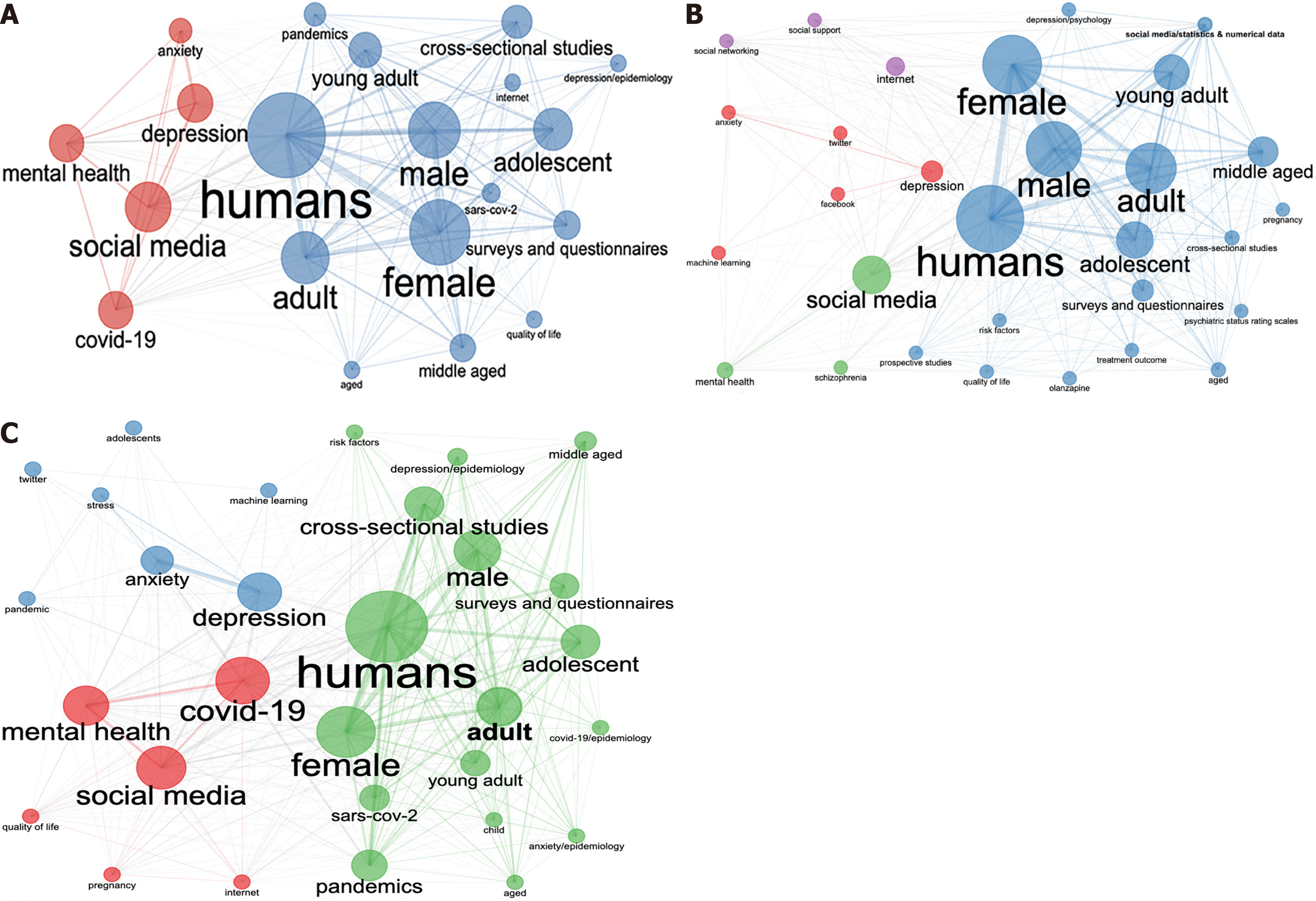

In general, the co-occurrence of keywords (Figure 7A) revealed that ‘humans’, ‘female’, ‘male’, ‘adult’, ‘adolescents’, and ‘social media’ were the keywords with high centrality. These keywords occupied an important position in the network and were closely correlated with other terms. Among them, ‘social media’ was closely related to ‘depression’, ‘mental health’, ‘COVID-19’, and ‘anxiety’; ‘humans’ was closely associated with demographic indicators such as ‘female’ ‘male’, ‘adult’, and ‘adolescents’, as well as with experimental methods such as ‘cross-sectional studies’, ‘surveys’, and ‘questionnaires’.

A comparison of the co-occurrence of keywords before and after COVID-19 (Figure 7B and C) revealed variations in the hot research topics after COVID-19 period. Certain new keywords occurred (Figure 7C), including COVID-19-related keywords (‘pandemic’ and ‘SARS-COV-2’) and psychology-related keywords (‘anxiety/epidemiology’, ‘depression/epidemiology’, and ‘stress’). In addition, some words were given additional weight, such as ‘depression’, ‘anxiety’, ‘mental health’, and ‘cross-sectional studies’, while other words decreased in proportion, including ‘middle-aged’. Several terms even disappeared after COVID-19, including ‘social support’, ‘social networking’, ‘Facebook’, and ‘olanzapine’.

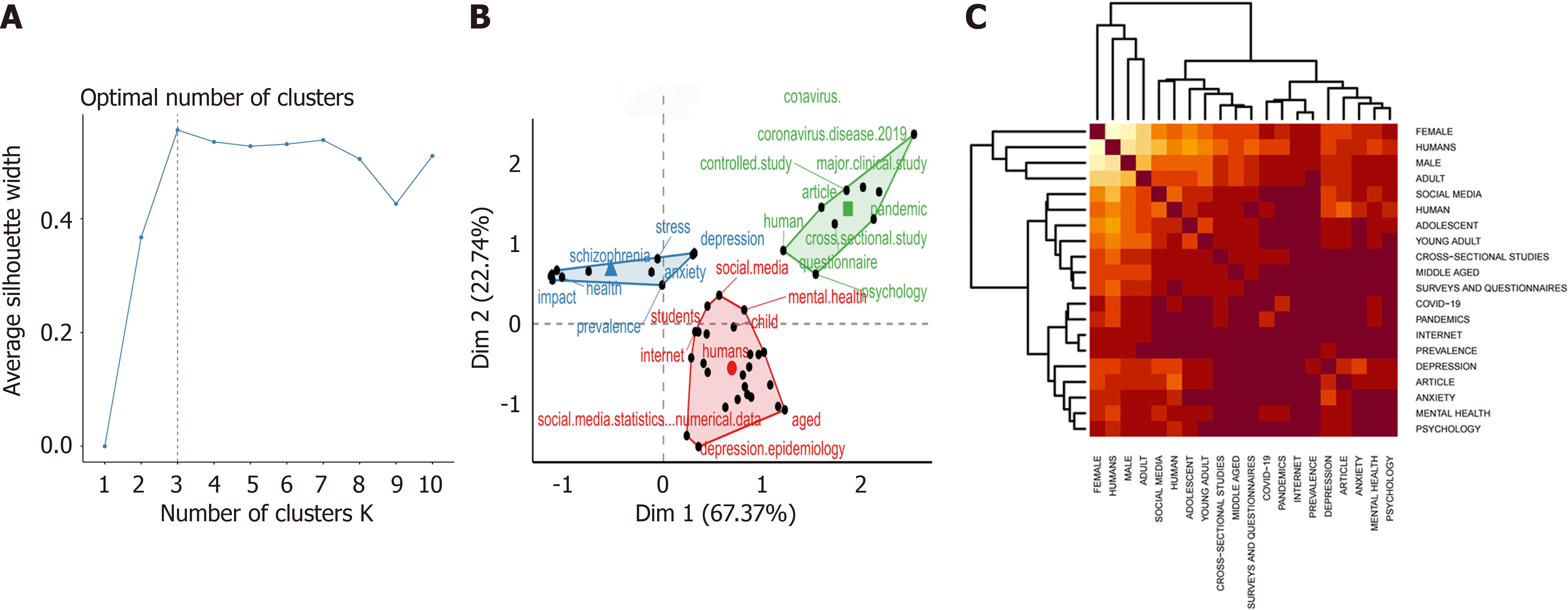

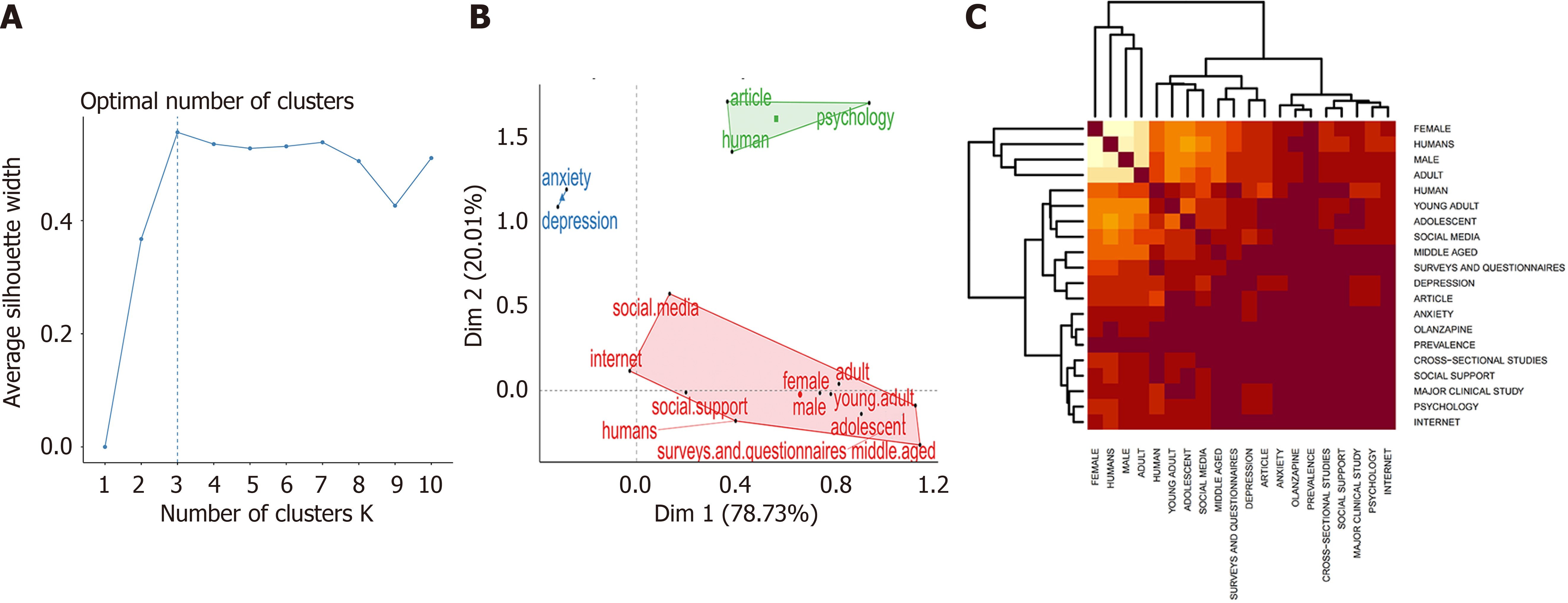

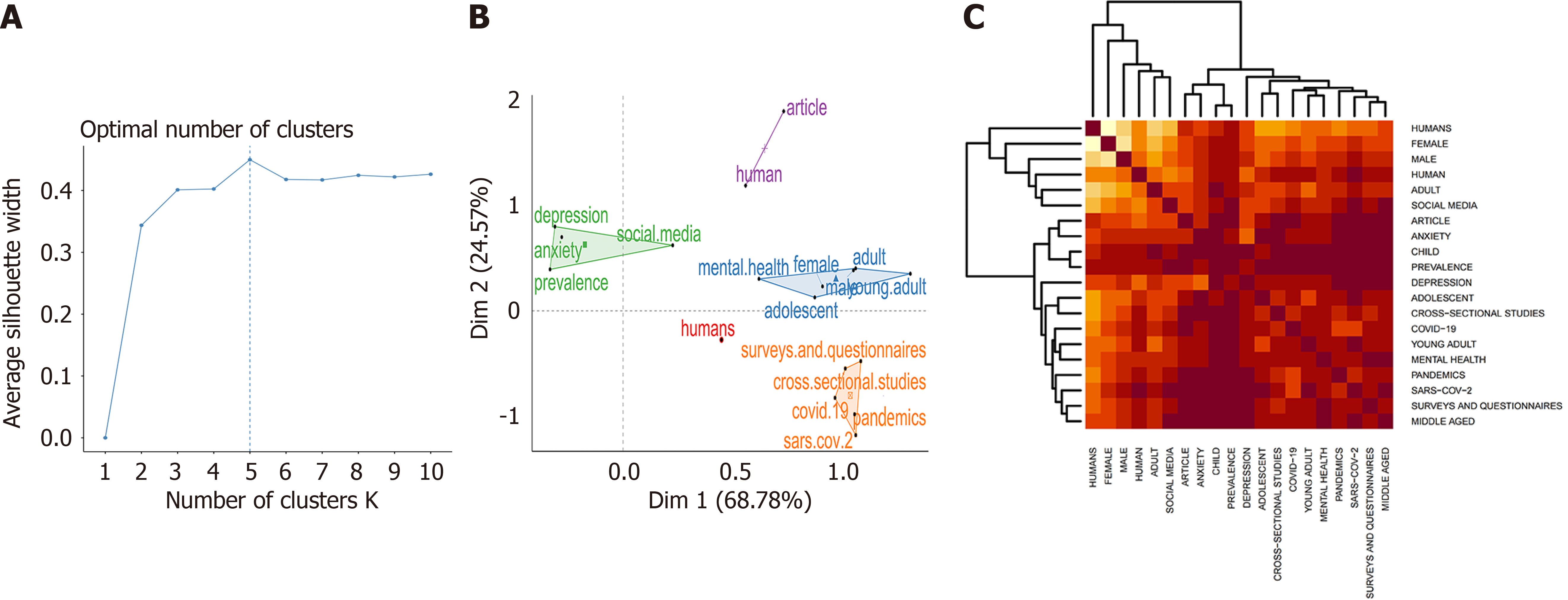

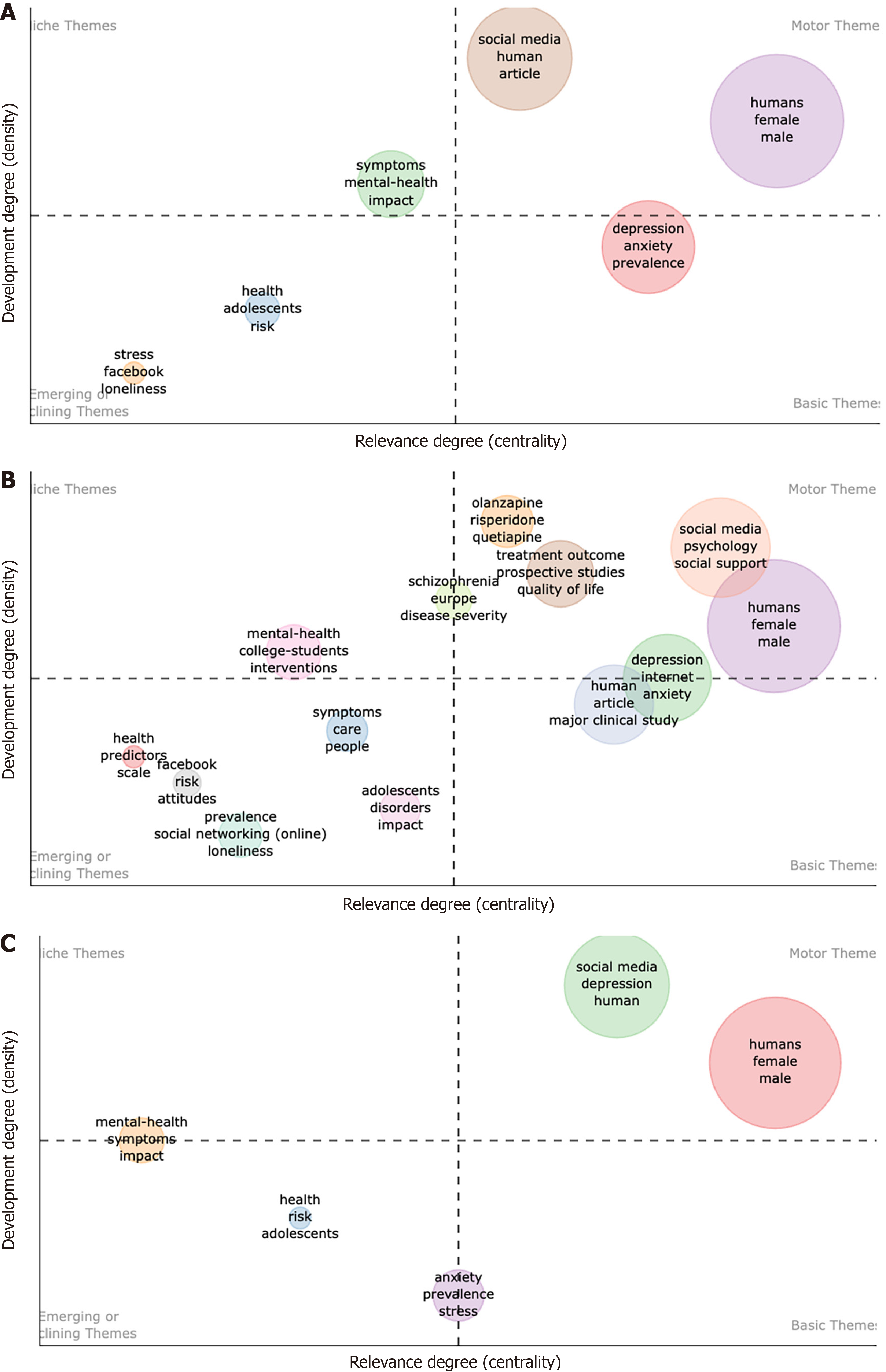

We performed further clustering to estimate the relationships between the various keywords. The average silhouette width indicated the optimal number of keyword clusters (Figures 8A, 9A and 10A). Overall, the optimal number of keyword clusters was three (Figure 8A). Cluster 1 included illnesses and symptoms (blue), including ‘schizophrenia’, ‘anxiety’, ‘depression’, ‘stress’, and ‘mental health’. Cluster 2 included ‘children’, ‘students’, ‘aged’, ‘social media data’, ‘numerical data’, and ‘Internet’ (red). Cluster 3 included research methods (i.e., ‘questionnaires’, ‘clinical studies’, and ‘cross-sectional studies’) and COVID-19 (green; Figure 8B). The keyword heat map indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic was strongly associated with ‘anxiety’ and ‘depression’ (Figure 8C).

We then highlighted the distinct clusters influenced by COVID-19. Before COVID-19, the optimal number of clusters was three (Figure 9B), and olanzapine was strongly correlated with most keywords in the keyword heat map (Figure 9C). However, after COVID-19, the optimal clusters increased to five (Figure 10A). The first cluster (green) contained ‘depression’ and ‘anxiety’, while the second cluster (purple) contained ‘article’ and ‘psychology’. The third cluster (blue) contained demographically classified words, such as ‘adult’, ‘adolescent’, and ‘female’. The fourth cluster included ‘humans’. The fifth cluster contained COVID-19-related words, such as ‘COVID-19’, ‘pandemics’, and ‘surveys and questionnaires’ (Figure 10B). After COVID-19, the word with the strongest correlations with other words was ‘child’, followed by ‘COVID-19’, ‘depression’, and ‘mental health’ (Figure 10C). Importantly, we identified keyword motor themes to help future researchers view research themes and core areas more comprehensively.

In general, ‘humans’, ‘social media’, ‘female’, and ‘male’ appeared consistently in the top-right ‘motor themes’ quadrant (Figure 11A-C), both before and after COVID-19, indicating that human behaviour, social media use, and gender differences have always been hot topics in research on psychopathology and social media use. Worryingly, there were completely different distributions of other themes before and after COVID-19. Before COVID-19 (Figure 11B), the motor themes in the top-right quadrant included ‘olanzapine’, ‘risperidone’, ‘quetiapine’, and ‘treatment outcomes’, indicating that the direction of treatment and clinical trials related to these drugs were important, well developed, and fundamental for the structuring of this research field. The top-left quadrant referring to niche themes included ‘college students’, and ‘intervention’, reflecting that although the research directions related to these keywords were relatively mature, they had little influence in the field of research on psychopathology and social media use. Emerging or declining themes, located in the bottom-left quadrant, included keywords relating to statistics and epidemiology, such as ‘predictor’, ‘prevalence’, and ‘scale’, suggesting that they were weakly developed and marginal. The lower-right quadrant, indicating basic themes - that is, important topics related to the fundamental framework of this field - included such keywords as ‘clinical studies’, ‘Internet’, and ‘anxiety’; moreover, these keywords were located in close proximity to the motor themes, indicating that certain existing studies related to these keywords. However, these keywords were not explored in depth and should therefore be further investigated in the future. In addition, the keywords ‘schizophrenia’ and ‘disease severity’ appeared at the junction of the top-left and top-right quadrants, suggesting that the psychological problems caused by social media were gradually expanding and needed to be considered.

After the COVID-19 outbreak (Figure 11C), negative emotions became more widespread due to the long-term isolation, social distancing, declining income, and health damage caused by the pandemic. The term ‘depression’ became a hot topic in the motor theme quadrant. Words such as ‘mental health’, ‘symptoms’, and ‘impact’ appeared at the boundary between niche themes and emerging or declining themes. Keywords such as ‘health’, ‘risk’, and ‘adolescents’ appeared in emerging or declining themes, suggesting that such studies were going through periods of upswing or downswing. Keywords such as ‘anxiety’, ‘prevalence’, and ‘stress’ appeared at the boundary between emerging or declining themes and basic themes, suggesting that studies related to these keywords might move from one topic to another or make connections between different topics.

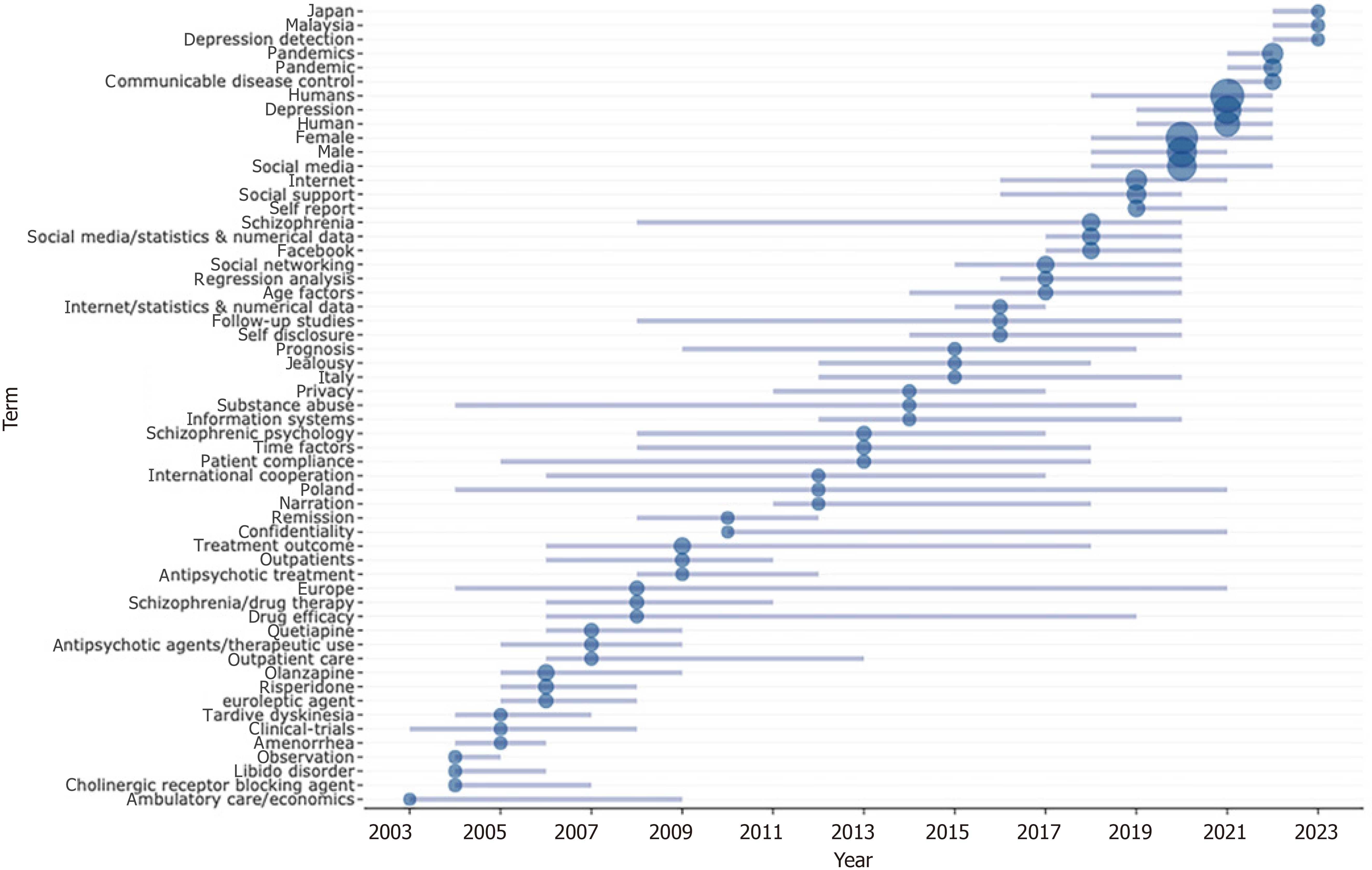

We further analysed the trends in the keywords. The discontinuous lines in Figure 12 represent the duration of a keyword burst, and the size of a circle represents the intensity of the burst. Keyword bursts can be roughly divided into three periods. In the first period (before 2010), the main keywords related to traditional medical treatments were ‘olanzapine’, ‘quetiapine’, and ‘drug efficacy’. In the second stage (2011-2018), the main keywords were related to social media platforms and data mining (i.e., ‘Facebook’, ‘Internet/statistics’, and ‘social media/statistics’). In the third stage (after 2019), the main keywords were ‘depression’ and ‘depression detection’. In addition, the keywords with the highest intensity were concentrated in studies published between 2019 and 2021.

A total of 4588 published papers were retrieved for our study, including 4350 research papers and 238 review papers (Figure 1). Research papers were published primarily in computer science and social behaviour journals, as well as medical and health sciences journals (Table 2). Among the top 10 most impactful journals for research on psychopathology and social media use, the Journal of Medical Internet Research (with the highest h-index) fell into the journal citation report quartile 1 (JCR Q1). This journal is the world’s leading digital health journal, focusing on medical devices, applications, and related health education and clinical care. Altogether, we identified 12205 authors, 6616 research institutions, and 117863 references. In terms of authors and institutions, prolific authors and institutions were at the centre of the collaborative networks (Table 1, Figures 4-6). Furthermore, regarding the distribution by country, research on psychopathology and social media use was concentrated in developed countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, while research collaboration was also led by these countries (Figures 3-6). This phenomenon could be partially explained by the fact that the internet was better developed in these countries, since Google, Microsoft, Apple, Facebook, and other internet giants were founded in the United States. According to a 2021 survey by the Pew Research Center, 48% of American adults said they obtained information from social media[24]. Internet users also produce large amounts of network information data, providing a wealth of information for scientific research purposes. However, high-income countries invest heavily in scientific research and devote more attention to psychopathology. For example, the United States (one of the countries that published the most papers) has relatively high per capita health expenditure, which reached $10784 in 2021[25]. The international cooperation network was also led by the United States (Figures 4-6), reflecting a global imbalance in the research output in this field. Developing countries produced fewer research publications, which did not mean they suffered less from social-media-induced mental illness. On the contrary, social-media-induced internet addiction, anxiety, and depression are common in developing countries[26]. Therefore, cooperation between research groups in developing countries and those in developed countries would enable patients with social-media-induced mental illnesses to receive better medical care. Encouragingly, some developing countries, such as Bangladesh and China, have been expanding their investments in research on psychopathology and social media use. In addition, the comparison of the situations before and after COVID-19 revealed that Lebanon and South Africa, which had no collaboration with the other countries before COVID-19 (Figure 5), cooperated extensively with other countries after COVID-19 (Figure 6). Therefore, it can be inferred that research in this field will continue to develop significantly in the next few years. We further explored the possible subdivisions of the field through keyword analysis to provide references for future researchers.

We summarized the commonly used methods in research on psychopathology and social media use (Figures 7-10) and found that cross-sectional studies, questionnaires, and meta-analyses were the most commonly used methods. These research methods are traditional research methods in this field, and each has its own advantages. Cross-sectional studies are highly efficient, low cost, and can investigate multiple variables[27]; questionnaire surveys are anonymous, and the related data analysis is relatively easy[28]; meta-analyses are comprehensive and can provide extremely accurate findings[29]. However, these traditional methods also have certain limitations. In the case of a questionnaire survey, for example, the process of questionnaire completion, collection, and analysis is long and burdensome. Moreover, it is difficult to guarantee the compliance of the subjects and the reliability of the questionnaire completion, and the objectivity of the data may therefore be compromised. As can be seen from the second and third stages of the trends (Figure 12), an integrated approach that combines computational linguistics and clinical psychology is likely to become more popular in research on psychopathology and social media use in the future. For example, based on traditional psychological experimental and observational research, web crawlers could be used to collect data, and natural language processing could be used to analyse the psychological states and social interaction patterns of internet users and the impact of social media on different groups of people. These methods of information collection and analysis using big data align well with the characteristics of social media platforms. In addition, information analysis technologies based on artificial intelligence algorithms and models can accurately reflect the psychological states of internet users and reduce research costs. Similar approaches are useful for conducting complex, systematic large-scale experimental studies over long research periods, such as major clinical studies (Figure 11).

Through keyword analysis, in addition to the commonly used methods, we identified the main themes and progress in research on psychopathology and social media use. Our study found that mental illness was not affected by platform discrepancies, and the inappropriate use of any social media platform was likely to trigger pathological psychological states. Existing research has highlighted gender differences in social media use and psychopathological consequences (Figures 7-12) due to the differences in the biological structures and social media use patterns of men and women. Men’s androgen levels are higher than women’s, making them likely to be excited by online sensory stimulation; therefore, they tend to use the internet and mobile apps for longer periods than women[30]. Some studies have found that men are better than women at spatial perception[31], hand-eye coordination[32], and competitive activities[33]. Therefore, they generally prefer sports, technology, politics, and other topics on social media[34], whereas women are more inclined to share family and personal details and other content on social media[35]. Consequently, men, and women face different mental health risks. Men are likely to fall into online game addiction, online gambling, and other destructive behaviours and are more psychologically dependent on the internet than women[36]. In addition, men who are often exposed to violence, pornography, profanity, and other negative content on social media platforms may tend to experience negative emotions, such as anxiety, depression, and anger. They may be unable to resist the temptation of such content and become addicted to it, which causes physical and mental damage[37]. Women may be more susceptible to social anxiety[38], and their negative self-images, perceptions, and behaviours may be significantly worsened by social media use. On the one hand, social media presents many images of beautiful, fashionably dressed women that may exert cultural pressure on females, resulting in women internalizing these standards for their external images to a significantly greater degree than men[26]. On the other hand, image consumption caused by consumerism attracts more women; capitalists encourage women to fall into a cycle of ‘social aesthetic to appearance anxiety to body consumption’ by presenting the external image they believe women should have. However, it is important to note that gender differences are not absolute. All people are independent individuals and exhibit different behaviours when using social media due to their own experiences, ideas, and interests. Therefore, we should not simply categorize people’s social media use by gender or draw simple con

Research has demonstrated that excessive use of social media is associated with anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and internet addiction, which can negatively affect people’s offline lives (Figure 7)[18,39]. Some researchers have studied psychopathological drug treatments, such as olanzapine[40], risperidone[41], and quetiapine[42]. Drug therapy has the advantages of convenience, efficiency, and speed, but it does not cure the root causes of the pathological problems caused by social media and may result in relatively severe drug dependence and side effects[43]; its limitations are therefore obvious. In recent years, with the steady transformation of the medical model from a traditional model to a bio-psychosocial one, psychosocial factors have increasingly been emphasized by scholars in this field, leading to the emergence of the ‘social support’ topical trend in 2017 (Figure 12) and the ‘depression detection’ burst in 2021. In recent years, with the rapid development of artificial intelligence and machine learning technology, traditional depression detection methods, such as psychological assessment, have been supplemented by new depression detection tools based on data analysis and algorithmic models[44]. These tools can determine whether a person is depressed by analysing various data, including voice, text, and images, thus providing doctors with faster and more accurate diagnosis and treatment recommendations. Neurobiological[45] or sociological[46] approaches also offer new hope. Neurobiological methods, such as electrotherapy and magnetic therapy, can help alleviate depression and anxiety symptoms by stimulating neuronal activity[47], and neurofeedback, such as electroencephalography, can support patients’ self-regulation[48]. In addition, from a sociological perspective, it is extremely important to detect and evaluate patients’ interpersonal and family problems and guide them in effectively coping with work, financial, and interpersonal pressures when treating certain illnesses, such as depression (Figure 8). Future researchers should conduct a more in-depth exploration of these aspects.

In addition, it is worth noting that COVID-19 is a very important emerging direction for research on psychopathology and social media use. There was a huge difference in literature output before and after COVID-19, and a surge after COVID-19 (Figure 2). The co-occurrence of keywords (Figure 7) demonstrated that COVID-19 was strongly correlated with anxiety and depression. The use of social media increased dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic due to social media becoming an important channel for people to obtain information, exchange emotions, and relieve psychological pressure[49]. However, social media is laden with negative information, disinformation, and rumours, and constant exposure to this information can trigger feelings of anxiety and depression. During COVID-19, people may have felt that they could not present positive images of their lives and achievements to others on social media[50], resulting in anxiety and depression due to social comparisons and self-burden issues. Overreliance on social media and neglect of offline social interactions also caused anxiety and depression during COVID-19[51]. Moreover, the onset of anxiety and depression is related to people’s excessive concern and fear of coronavirus disease, with this corona-phobia likely stemming from the unknown nature of the virus, panic over the disease, or reactions to the overwhelming spread of alarming information on social media. This has significantly influenced the public’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The complex psychological states fostered by social media platforms during the pandemic made the formulation and implementation of psychological interventions particularly important, and social media offered a platform for health promotion. If academics and healthcare professionals can effectively identify the needs of patients on social media platforms and provide timely interventions, similar public health emergencies may be prevented from causing widespread mental disorders.

After COVID-19, the term ‘child’ became a hot topic in research on psychopathology and social media use, as pre

This study did have certain limitations. First, we retrieved English-language papers only, which may have led to bias in language selection and some valuable non-English-language papers being missed. In addition, we selected only the WOSCC, PubMed, and Scopus databases as data sources; other platforms were not used. Despite these limitations, we have included most of the global studies in this field, and through bibliometric evaluation, we have suggested implications for future research on psychopathology and social media use based on empirical evidence.

This is the first bibliometric study to systematically analyse research on pathology and social media use. We identified prolific authors, institutions, and journals in this field, and went on to identify current collaboration networks, research frameworks, and trends through keyword analysis. The main topics in this field focused on specific mental illnesses, populations, and clinical treatments, and we observed that research on gender differences in psychopathological states was relatively mature. In the future, more in-depth clinical studies should be conducted, and more advanced artificial intelligence algorithms and models should be applied. In addition, more attention should be paid to psychopathological prevalence and detection targeting different groups of people. The research results reflected an increased level of concern about mental health issues after COVID-19 and a changing emphasis on social media use and the impact of public health emergencies. We hope that this study will provide useful insights to enable health managers, psychologists, and other health workers to determine future research directions and encourage them to better utilize social media platforms for their professional work, such as health policy advocacy, peer communication, and crisis intervention for mental illness. Future researchers should continue to strengthen their international cooperation, explore research methods that align with the information age, and develop novel treatments for mental illnesses caused by social media.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Director of the Pathology Branch of Guangxi Medical Association in China.

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Stoyanov D, Bulgaria S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Twenge JM, Joiner TE. U.S. Census Bureau-assessed prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37:954-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 55.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Venegas-Vera AV, Colbert GB, Lerma EV. Positive and negative impact of social media in the COVID-19 era. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2020;21:561-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Alvarez-Jimenez M, Alcazar-Corcoles MA, González-Blanch C, Bendall S, McGorry PD, Gleeson JF. Online, social media and mobile technologies for psychosis treatment: a systematic review on novel user-led interventions. Schizophr Res. 2014;156:96-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Throuvala MA, Griffiths MD, Rennoldson M, Kuss DJ. Perceived Challenges and Online Harms from Social Media Use on a Severity Continuum: A Qualitative Psychological Stakeholder Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Berryman C, Ferguson CJ, Negy C. Social Media Use and Mental Health among Young Adults. Psychiatr Q. 2018;89:307-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sherer J, Levounis P. Technological Addictions. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2022;45:577-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Forte G, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Casagrande M. COVID-19 Pandemic in the Italian Population: Validation of a Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire and Prevalence of PTSD Symptomatology. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yao F, Sun X, Yu H, Zhang W, Liang W, Fu K. Mimicking the Brain's Cognition of Sarcasm From Multidisciplines for Twitter Sarcasm Detection. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2023;34:228-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yeung AWK, Tosevska A, Klager E, Eibensteiner F, Tsagkaris C, Parvanov ED, Nawaz FA, Völkl-Kernstock S, Schaden E, Kletecka-Pulker M, Willschke H, Atanasov AG. Medical and Health-Related Misinformation on Social Media: Bibliometric Study of the Scientific Literature. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:e28152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ellis J, Ellis B, Tyler K, Reichel MP. Recent trends in the use of social media in parasitology and the application of alternative metrics. Curr Res Parasitol Vector Borne Dis. 2021;1:100013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Arruda H, Silva ER, Lessa M, Proença D Jr, Bartholo R. VOSviewer and Bibliometrix. J Med Libr Assoc. 2022;110:392-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Poly TN, Islam MM, Walther BA, Lin MC, Jack Li YC. Artificial intelligence in diabetic retinopathy: Bibliometric analysis. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2023;231:107358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sofyantoro F, Frediansyah A, Priyono DS, Putri WA, Septriani NI, Wijayanti N, Ramadaningrum WA, Turkistani SA, Garout M, Aljeldah M, Al Shammari BR, Alwashmi ASS, Alfaraj AH, Alawfi A, Alshengeti A, Aljohani MH, Aldossary S, Rabaan AA. Growth in chikungunya virus-related research in ASEAN and South Asian countries from 1967 to 2022 following disease emergence: a bibliometric and graphical analysis. Global Health. 2023;19:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xu Y, Jiang Z, Kuang X, Chen X, Liu H. Research Trends in Immune Checkpoint Blockade for Melanoma: Visualization and Bibliometric Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:e32728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cascini F, Pantovic A, Al-Ajlouni YA, Failla G, Puleo V, Melnyk A, Lontano A, Ricciardi W. Social media and attitudes towards a COVID-19 vaccination: A systematic review of the literature. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;48:101454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Lahiri D, Lavie CJ. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:779-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1000] [Cited by in RCA: 948] [Article Influence: 189.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LMW, Gill H, Phan L, Chen-Li D, Iacobucci M, Ho R, Majeed A, McIntyre RS. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2424] [Cited by in RCA: 3008] [Article Influence: 601.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schou Andreassen C, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z, Mazzoni E, Pallesen S. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30:252-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 574] [Cited by in RCA: 796] [Article Influence: 88.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kramer AD, Guillory JE, Hancock JT. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8788-8790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1504] [Cited by in RCA: 725] [Article Influence: 65.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Li S, Wang Y, Xue J, Zhao N, Zhu T. The Impact of COVID-19 Epidemic Declaration on Psychological Consequences: A Study on Active Weibo Users. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1165] [Cited by in RCA: 824] [Article Influence: 164.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, Wang Y, Fu H, Dai J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0231924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1367] [Cited by in RCA: 1299] [Article Influence: 259.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | O'Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K; Council on Communications and Media. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics. 2011;127:800-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 898] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Woods HC, Scott H. #Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J Adolesc. 2016;51:41-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 472] [Article Influence: 52.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Reis D, Fricke O, Schulte AG, Schmidt P. Is examining children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders a challenge?-Measurement of Stress Appraisal (SAM) in German dentists with key expertise in paediatric dentistry. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0271406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Herzler M, Abedini J, Allen DG, Germolec D, Gordon J, Ko HS, Matheson J, Reinke E, Strickland J, Thierse HJ, To K, Truax J, Vanselow JT, Kleinstreuer N. Use of human predictive patch test (HPPT) data for the classification of skin sensitization hazard and potency. Arch Toxicol. 2024;98:1253-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Thapa B, Torres I, Koya SF, Robbins G, Abdalla SM, Arah OA, Weeks WB, Zhang L, Asma S, Morales JV, Galea S, Rhee K, Larson HJ. Use of Data to Understand the Social Determinants of Depression in Two Middle-Income Countries: the 3-D Commission. J Urban Health. 2021;98:41-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hoenink JC, Mackenbach JD, van der Laan LN, Lakerveld J, Waterlander W, Beulens JWJ. Recruitment of Participants for a 3D Virtual Supermarket: Cross-sectional Observational Study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5:e19234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Benson T, Sladen J, Liles A, Potts HWW. Personal Wellbeing Score (PWS)-a short version of ONS4: development and validation in social prescribing. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8:e000394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Liu SY, Liao Y, Hosseinifard H, Imani S, Wen QL. Diagnostic Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:705791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yue H, Zhang X, Cheng X, Liu B, Bao H. Measurement Invariance of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale Across Genders. Front Psychol. 2022;13:879259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sykes Tottenham L, Saucier DM, Elias LJ, Gutwin C. Men are more accurate than women in aiming at targets in both near space and extrapersonal space. Percept Mot Skills. 2005;101:3-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pavlinac Dodig I, Krišto D, Lušić Kalcina L, Pecotić R, Valić M, Đogaš Z. The effect of age and gender on cognitive and psychomotor abilities measured by computerized series tests: a cross-sectional study. Croat Med J. 2020;61:82-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Matud MP, Díaz A. Gender, exercise, and health: A life-course cross-sectional study. Nurs Health Sci. 2020;22:812-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tsutsui H, Nomura K, Kusunoki M, Ishiguro T, Ohkubo T, Oshida Y. Gender differences in the perception of difficulty of self-management in patients with diabetes mellitus: a mixed-methods approach. Diabetol Int. 2016;7:289-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lee JY, Lee E. What topics are women interested in during pregnancy: exploring the role of social media as informational and emotional support. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Dong G, Zheng H, Liu X, Wang Y, Du X, Potenza MN. Gender-related differences in cue-elicited cravings in Internet gaming disorder: The effects of deprivation. J Behav Addict. 2018;7:953-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Davis JP, Christie NC, Lee D, Saba S, Ring C, Boyle S, Pedersen ER, LaBrie J. Temporal, Sex-Specific, Social Media-Based Alcohol Influences during the Transition to College. Subst Use Misuse. 2021;56:1208-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zhao N, Zhou G. Social Media Use and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Moderator Role of Disaster Stressor and Mediator Role of Negative Affect. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2020;12:1019-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Wong HY, Mo HY, Potenza MN, Chan MNM, Lau WM, Chui TK, Pakpour AH, Lin CY. Relationships between Severity of Internet Gaming Disorder, Severity of Problematic Social Media Use, Sleep Quality and Psychological Distress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 44.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Caldiroli A, Capuzzi E, Tagliabue I, Capellazzi M, Marcatili M, Mucci F, Colmegna F, Clerici M, Buoli M, Dakanalis A. Augmentative Pharmacological Strategies in Treatment-Resistant Major Depression: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Robinson DG, Gallego JA, John M, Hanna LA, Zhang JP, Birnbaum ML, Greenberg J, Naraine M, Peters BD, McNamara RK, Malhotra AK, Szeszko PR. A potential role for adjunctive omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for depression and anxiety symptoms in recent onset psychosis: Results from a 16 week randomized placebo-controlled trial for participants concurrently treated with risperidone. Schizophr Res. 2019;204:295-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Suttajit S, Srisurapanont M, Maneeton N, Maneeton B. Quetiapine for acute bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:827-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Webster LR. Risk Factors for Opioid-Use Disorder and Overdose. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:1741-1748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 40.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Salas-Zárate R, Alor-Hernández G, Salas-Zárate MDP, Paredes-Valverde MA, Bustos-López M, Sánchez-Cervantes JL. Detecting Depression Signs on Social Media: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Wang YQ, Li R, Zhang MQ, Zhang Z, Qu WM, Huang ZL. The Neurobiological Mechanisms and Treatments of REM Sleep Disturbances in Depression. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13:543-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Thurtle V. Post-natal depression: the relevance of sociological approaches. J Adv Nurs. 1995;22:416-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Wang S, Mao S, Yao B, Xiang D, Fang C. Effects of low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on depression- and anxiety-like behaviors in epileptic rats. J Integr Neurosci. 2019;18:237-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Lin Z, Liu J, Duan F, Liu R, Xu S, Cai X. Electroencephalography Symmetry in Power, Waveform and Power Spectrum in Major Depression. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2020;2020:5280-5283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Xu B, Ng MSN, So WKW. A review of the prevalence, associated factors and interventions of psychological symptoms among cancer patients in the Chinese Mainland during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ecancermedicalscience. 2021;15:1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Huang HY. Third- and First-Person Effects of COVID News in HBCU Students' Risk Perception and Behavioral Intention: Social Desirability, Social Distance, and Social Identity. Health Commun. 2023;38:2956-2970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Cheng C, Lau YC. Social Media Addiction during COVID-19-Mandated Physical Distancing: Relatedness Needs as Motives. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Schwartz-Lifshitz M, Hertz-Palmor N, Dekel I, Balan-Moshe L, Mekori-Domachevsky E, Weisman H, Kaufman S, Gothelf D, Amichai-Hamburger Y. Loneliness and Social Media Use Among Adolescents with Psychiatric Disorders. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2022;25:392-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Munzer T, Torres C, Domoff SE, Levitt KJ, McCaffery H, Schaller A, Radesky JS. Child Media Use During COVID-19: Associations with Contextual and Social-Emotional Factors. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2022;43:e573-e580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Andreassen CS, Pallesen S, Griffiths MD. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addict Behav. 2017;64:287-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 54.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Kross E, Verduyn P, Demiralp E, Park J, Lee DS, Lin N, Shablack H, Jonides J, Ybarra O. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 706] [Cited by in RCA: 528] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |