Published online May 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i5.726

Revised: April 5, 2024

Accepted: April 11, 2024

Published online: May 19, 2024

Processing time: 91 Days and 0.7 Hours

The management of offenders with mental disorders has been a significant concern in forensic psychiatry. In Japan, the introduction of the Medical Tr

To explore current as well as optimized learning strategies for risk assessment in AIH decision making.

We conducted a questionnaire survey among designated psychiatrists to explore their experiences and expectations regarding training methods for psychiatric assessments of offenders with mental disorders.

The findings of this study’s survey suggest a prevalent reliance on traditional learning approaches such as oral education and on-the-job training.

This underscores the pressing need for structured training protocols in AIH consultations. Moreover, feedback derived from inpatient treatment experiences is identified as a crucial element for enhancing risk assessment skills.

Core Tip: In this study, we clarified that many Japanese psychiatrists rely on traditional learning approaches such as oral education and on-the-job training for learning risk assessment skills. Some structured training protocols as well as feedback derived from inpatient treatment experiences are needed for improving skills of practitioners engaging in administrative involuntary hospitalization.

- Citation: Shiina A, Niitsu T, Iyo M, Fujii C. Need for education of psychiatric evaluation of offenders with mental disorders: A questionnaire survey for Japanese designated psychiatrists. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(5): 726-734

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i5/726.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i5.726

The management of offenders with mental disorders has been a longstanding focus of discussion among general and forensic mental health specialists. Numerous experts acknowledge that solely punishing offenders is unlikely to deter recidivism, particularly in cases where the offense stems directly from psychiatric symptoms. Instead, there is a consensus that appropriate psychiatric treatment is necessary to facilitate their reintegration into society[1,2].

As a result, most legal systems and societies require the establishment of criminal responsibility before imposing sanctions on offenders. Those who commit crimes while deemed legally insane as a result of mental disorders are typically exempt from punishment. This principle is widely regarded as rational in most developed countries, for several reasons[3].

With regards to Japanese legislation, an act of insanity is not punishable, and an act of diminished responsibility shall lead to punishment being reduced, according to Article 39 of the Penal Code. Insanity is defined by the Supreme Court as the inability to recognize the disparity between good and evil as well as control oneself as a result of mental disorders. Diminished responsibility is defined as a state in which these abilities are strongly impaired as a result of mental disorders. However, for many years, Japan had no specific legal provisions for offenders with mental disorders. They were treated under the Mental Health and Welfare Act.

Post-debate, the Act on Medical Care and Treatment for Persons Who Have Caused Serious Cases under the Condition of Insanity (abbreviated to the Medical Treatment and Supervision Act, or MTS Act) was enacted in 2005, coinciding with the widespread reform of the Japanese forensic mental health system[4]. Under this new scheme, individuals committing a serious criminal offense while insane or having diminished responsibility are dealt with within a judicial and administrative framework. The enactment of the MTS Act also meant that clinical psychiatrists would have the opportunity to collaborate with legal professionals, such as judges and lawyers in the treatment of offenders. Additionally, judges faced the necessity of learning about clinical psychiatry for appropriate decision-making under the MTS Act.

Conversely, offenders who are not identified as not guilty by reason of insanity or as having diminished responsibility are treated the same as in the past. In addition, offenders who committed less serious crimes under the influence of mental disorders were not subjected to the MTS Act. Both can be considered to be subjected to an administrative involuntary hospitalization (AIH) scheme that was established in 1950. This scheme was succeeded by the Mental Health and Welfare Act (amended in 2013) without any major alterations. Under this scheme, if an individual is recognized as being at risk of harming themselves or others as a result of a mental disorder, the police and prosecutor report the case to the prefectural governor. The governor can then order the individual to be hospitalized in a designated psychiatric hospital based on an assessment by two designated psychiatrists that involuntary hospitalization is necessary[5].

However, legislation regarding the content of treatment under AIH by the prefectural governor’s order is scarce. In addition, compared to the scheme of the MTS Act, AIH has rarely been discussed, even in academia. There are few published national reports on the performance and outcomes of AIH. In particular, the standard for inducing the AIH scheme is too vague to be appropriately managed. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare published an official notice regarding the standard of AIH in 1961, as “Guidelines for Handling Administrative Involuntary Hospitalization and Consent Hospitalization for Patients with Mental Disorder”. Although the scheme of Consent Hospitalization was abolished in 1988, the AIH standard described in this article is still in effect. This standard should be criticized as being outdated. For instance, psychopathy has been illustrated as an example of AIH. However, most Japanese psychiatrists and police officers believe that psychopathic offenders should be punished for their crimes as opposed to being hospitalized involuntarily into psychiatric hospitals.

Furthermore, the criteria for determining whether patients should undergo AIH remain unclear. In Japan, the proficiency in psychiatric assessment of offenders with mental disorders, particularly for establishing criminal responsibility in court trial, has garnered significant attention among specialists. While training seminars on psychiatric assessment are held several times a year, the focus on AIH-related skills, including risk assessment and patient management, has been largely overlooked since the inception of the AIH scheme in the 1950s. To our knowledge, there exists only one textbook authored by Nishiyama[6] in 1984 that outlines the consultation method for AIH cases. Moreover, there is a notable absence of lectures or seminars aimed at equipping professionals with the necessary skills to effectively evaluate patients in AIH decision-making sessions.

In the United Kingdom, forensic psychiatrists take a three-year course prior to gaining a status of a consultant. It includes a professional program with peer groups to learn how to assess and manage the risk of harm self or others in patients with mental disorder. In the United States, they take two-year fellowship program post completing residency in general psychiatry[7]. In contrast, there is no structured training course for forensic psychiatrists in Japan, while psychiatric examination for evaluating.

Considering this situation, there is a need for educational materials to assist young psychiatrists with efficiently learning the points to be considered by designated psychiatrists when they conduct diagnostic examinations for AIH in current psychiatric practice.

For the initial step in accomplishing the goal described above, a questionnaire survey of designated psychiatrists who are currently providing AIH consultation was conducted to obtain their opinions on the actual conditions of medical examinations and education on medical examinations as well as elucidate the expert consensus on the procedures and the need for medical examination training in the situation of AIH consultation.

In this study, the aim was to explore the resources utilized by practicing psychiatrists to enhance their skills in risk assessment of subjects undergoing AIH. Additionally, elucidating the perspectives of psychiatrists regarding the most effective methods for learning about psychiatric evaluations of such patients was included.

This study utilized a mail-based questionnaire survey of Japanese psychiatrists to clarify the current experience and future needs of the methods of education for psychiatric assessment with regards to offenders with mental disorders.

Psychiatrists belonging to a psychiatric hospital (either the public sector or the private sector) with a license of a designated psychiatrists were recruited as participants of the study. Psychiatrists of any gender, age, and ethnicity were welcomed, but participants were over 29 years old as a result of obtaining a designated psychiatrist license required at least 5 years of experience as a medical doctor. Individuals who had already been involved in this study or preceding studies at the start of this study were excluded.

We constructed a series of questionnaires written by Japanese post-discussion with an expert panel composed of research members who were leading psychiatrists. Several studies regarding this issue were referred to, as well as reports of relevant research published in the past[7,8]. In general, there are two ways to acquire new job skills: to learn knowledge by reading materials or attending seminars organized by experts, or to learn from professionals while practicing the skills on-the-job. Seminars regarding national legislation are often held by the government or related organizations. Conversely, Japan does not have a structural scheme in place for on-the-job training in the field of the AIH. Instead, several psychiatrists attended the consultation of other designated psychiatrists. Attendance at a designated psychiatrist's examination is one possible way to learn about the AIH skills[9]. In addition, the Expert Panel also discussed the possibility of improving the skills by learning more about the condition of inpatients at the designated hospitals in which they will be treated post-decision of the AIH. Based on these discussions, the ten types of ways for learning AIH examination skills were identified.

The questionnaire included options for learning about the risk assessment of offenders with mental disorders. The participants were asked to answer whether they had previously utilized these learning methods. They were also asked to evaluate the appropriateness of each method on a 9-point Likert scale. Furthermore, we gathered the participants’ working records (e.g., years of practice as a designated psychiatrist and number of cases they experienced for the evaluation in this year), as exhibited in Supplementary material.

In this study, our aim was to investigate the resources utilized by practicing psychiatrists to improve their skills in risk assessment for subjects undergoing AIH. Additionally, we sought to elucidate psychiatrists' perspectives on the most effective methods for learning about psychiatric evaluations of such patients.

We statistically analyzed the data utilizing the SPSS for Windows version 28 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States).

Firstly, each participant’s background data for presenting descriptive statistics was analyzed. Subsequently, the mean and 95%CI were calculated. A categorical rating of first-line, second-line, or third-line options were designated based on the lowest category in which the CI fell, with boundaries of 6.5 or greater for the first-line (preferred) options, 3.5 or greater but less than 6.5 for the second-line (alternate), and less than 3.5 for the third-line (usually inappropriate) options, respectively. Among the first-line options, the option referred to as “best recommendation/essential” was defined, which approximately 50% of the experts rated it 9. This analysis method was adopted after referring to an expert consensus series of guidelines. Finally, we conducted additional analyses to clarify the disparities in opinions between the groups of respondents. The level of significance in each analysis was established at P < 0.05.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine with the No. 1145, Dec 14, 2020. The survey was conducted anonymously by the researchers. Participants were considered to have provided informed consent to participate in the study when they returned the answer sheet. This study was registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN number 000047167).

The survey was conducted from May 2021 to February 2022. We distributed the questionnaire to a total of 1290 hospitals (93 public and 1197 private). Out of these, we received 571 answer sheets (183 from public hospitals, 380 from private hospitals, and 8 with unknown origins). Since the official count of designated psychiatrists in Japan is undisclosed, the response rate cannot be determined. However, according to records from 2022, there were a total of 3500 seats available for designated psychiatrists to attend official seminars (https://www.shiteii.com/update.php). Every designated psychiatrist in Japan is mandated to attend a seminar every five years. Based on this, it is estimated that there are approximately 17,500 actively practicing designated psychiatrists. Therefore, we estimate that our survey captured opinions from approximately 3.3% of all designated psychiatrists in Japan.

The age of the respondents was 51.27 ± 11.07 years. The main characteristics of the respondents were as follows: Public hospital, 183; private hospital, 380; outpatient section of a general hospital without psychiatric beds, 2; outpatient clinic, 3; university and education/research facility, 2; and others, 1.

The primary psychiatric specialties were as follows: General psychiatry, 430; emergency psychiatry, 70; forensic mental health, 14; other psychiatric specialties, 22; education/research, 1; administration/management, 25; and others/invalid answers, 8. The mean years of psychiatric practice were 22.29 ± 11.79 years, with designated psychiatrists having 16.31 ± 10.88 years.

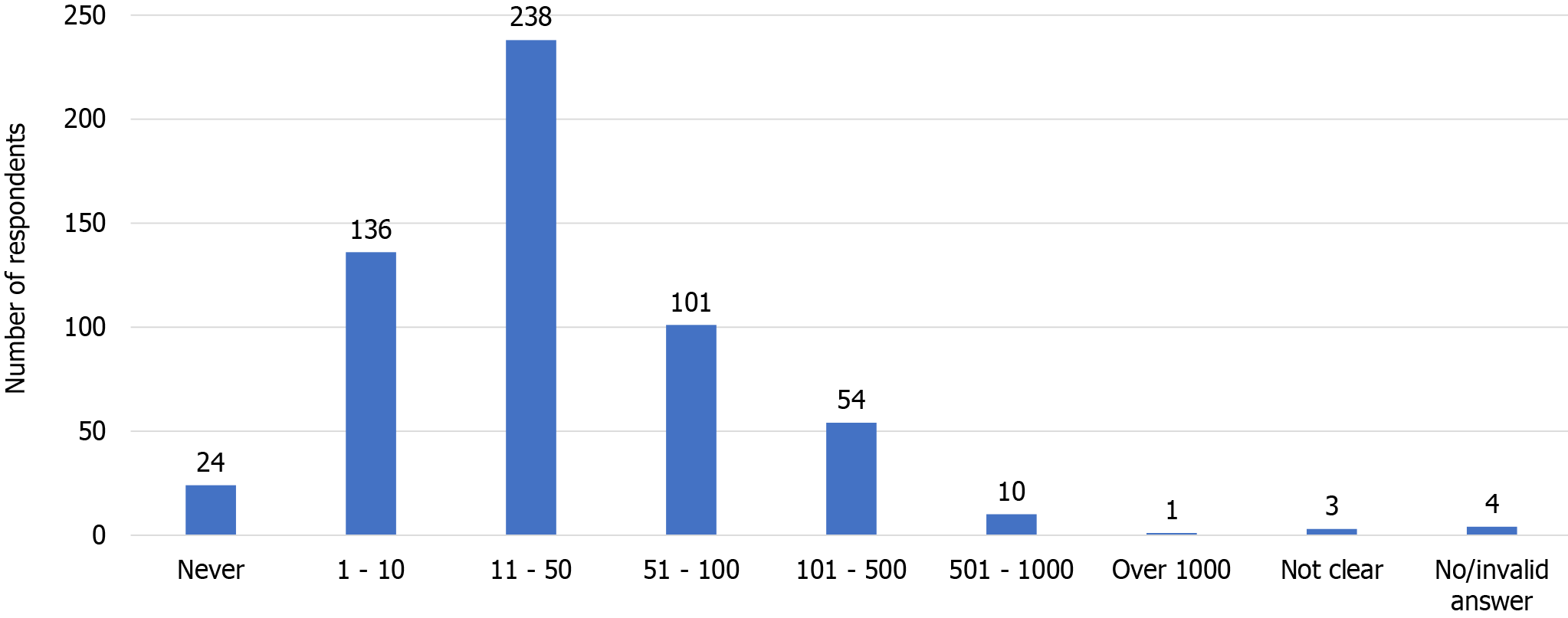

The numbers of cases of AIH consultation the respondents had conducted prior are exhibited in Figure 1. The mean number of AIH consultations per respondent in the latest year was 2.93 ± 3.96.

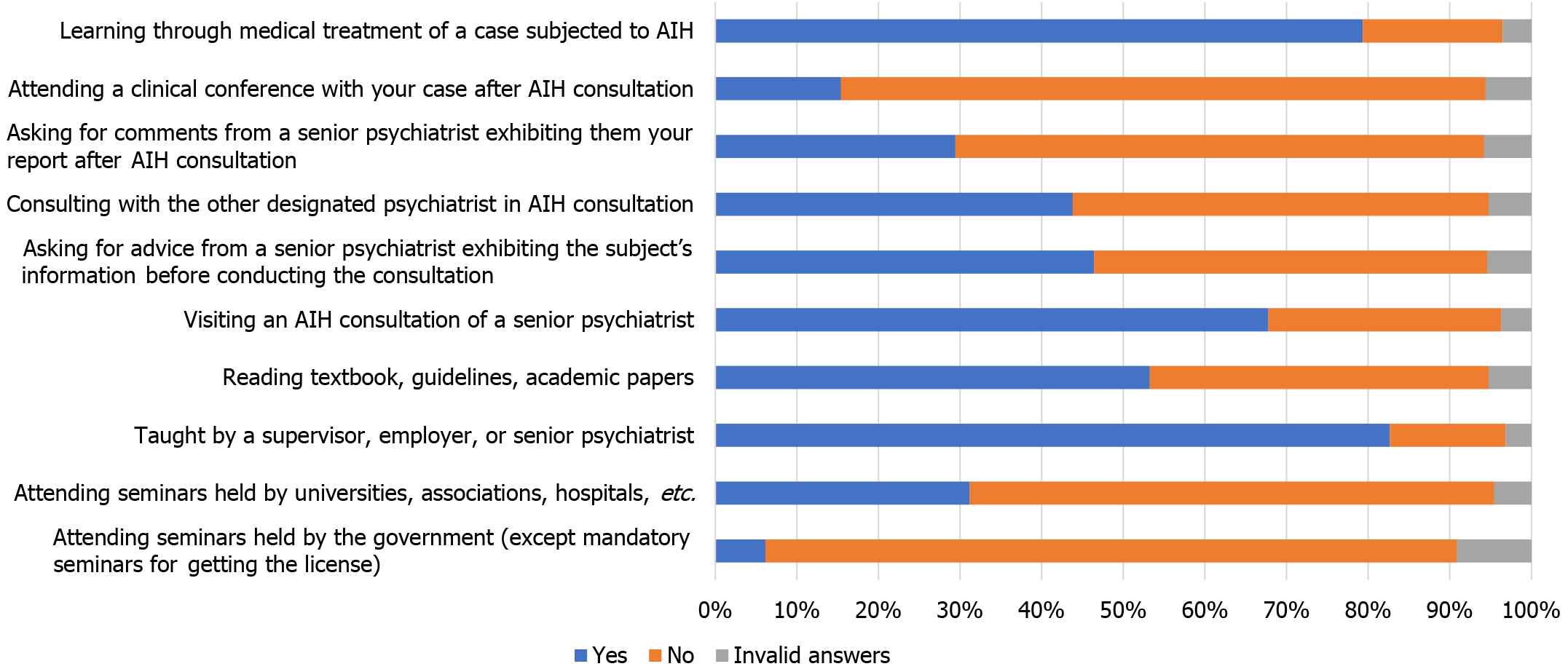

Ten learning methods were suggested to the respondents. Consequently, numerous psychiatrists have learned AIH consultation skills in several ways. The most common ways were through lectures from a supervisor/employer or senior psychiatrists, as well as learning through medical treatment of a patient who was subjected to AIH. Less than 10% attended an official seminar besides those mandatory to maintain the designated psychiatrist license. The detailed results are listed in Table 1 and Figure 2.

| Engaged in AIH consultation in the latest year | P value | |||

| Without | With | |||

| Attending seminars held by the government (except mandatory seminars for licensing) | Yes | 8 | 27 | NS |

| No | 118 | 366 | ||

| Attending seminars held by universities, associations, hospitals, etc. | Yes | 41 | 137 | NS |

| No | 90 | 277 | ||

| Taught by a supervisor, employer, or senior psychiatrists | Yes | 107 | 365 | NS |

| No | 26 | 55 | ||

| Reading textbook, guidelines, academic papers | Yes | 71 | 233 | NS |

| No | 57 | 180 | ||

| Visiting an AIH consultation of a senior psychiatrist | Yes | 84 | 303 | 0.037 |

| No | 49 | 114 | ||

| Asking for advice from a senior psychiatrist exhibiting the patient’s information prior to conducting the consultation | Yes | 42 | 223 | < 0.001 |

| No | 86 | 189 | ||

| Consulting with the other designated psychiatrist in AIH consultation | Yes | 57 | 193 | NS |

| No | 75 | 216 | ||

| Asking for comments from a senior psychiatrist exhibiting them your report post AIH consultation | Yes | 28 | 140 | 0.006 |

| No | 102 | 268 | ||

| Attending a clinical conference with your case post AIH consultation | Yes | 18 | 70 | NS |

| No | 113 | 338 | ||

| Learning through medical treatment of a case subjected to AIH | Yes | 112 | 341 | NS |

| No | 23 | 75 | ||

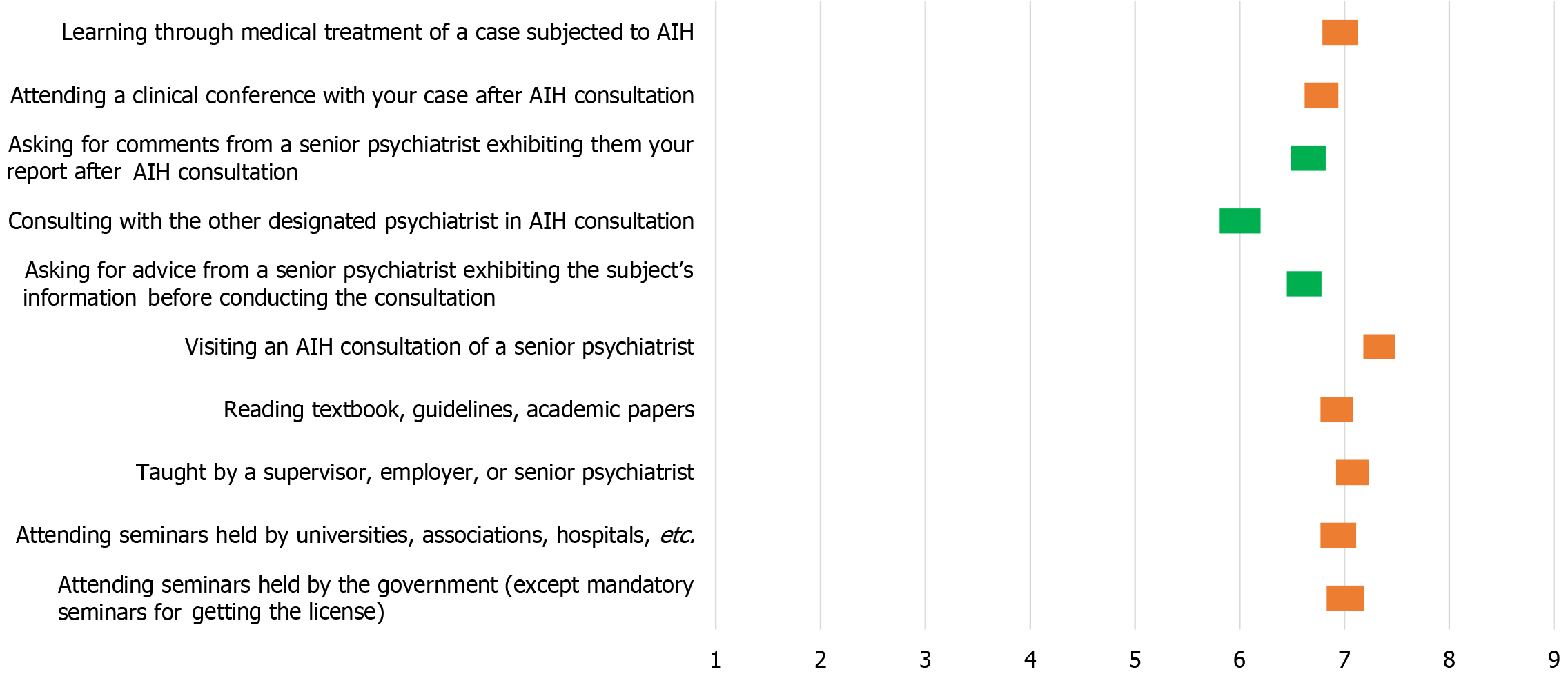

Each option was evaluated by the respondents utilizing a 9-point Likert scale. As a result, seven of the ten options were defined as the first-line according to the criteria suggested in the method section. Meanwhile, “Asking for advice from a senior psychiatrist exhibiting the subject’s information prior to conducting the consultation”, “Consulting with another designated psychiatrist”, and “Asking for comments from a senior psychiatrist and exhibiting them with your report post the AIH consultation” were categorized as second-line options. None of the items were defined as the “best recommendation/essential”. The results are exhibited in Figure 3.

We conducted two additional analyses to interpret the results. Initially, the study examined whether there were dis

Subsequently, an attempted to compare the disparities in opinions toward each method of learning about AIH consultation between the respondents’ specialties. The data of the respondents whose main specialties were general psychiatry and emergency psychiatry were extracted. As a result, three items (“Asking for comments from a senior psychiatrist showing them your report post the AIH consultation”, P = 0.031; “Attending a clinical conference with your case post the AIH consultation”, P = 0.002; “Learning through medical treatment of a case subjected to AIH”, P = 0.018) were significantly more valued by emergency psychiatrists as opposed to general psychiatrists in terms of learning AIH consultation. The results are presented in Table 2.

| Item | Contents | n | Mean | SD | Levene’s test for variance | Unpaired t test | ||||

| F value | P value | Variance equality | t value | u | P value | |||||

| Attending seminars held by the government (except mandatory seminars for licensing) | General | 428 | 6.92 | 2.180 | 0.248 | 0.618 | Yes | -1.537 | 495 | NS |

| Emergency | 69 | 7.35 | 2.078 | |||||||

| Attending seminars held by universities, associations, hospitals, etc. | General | 429 | 6.85 | 2.045 | 0.131 | 0.718 | Yes | -1.576 | 497 | NS |

| Emergency | 70 | 7.26 | 1.886 | |||||||

| Taught by a supervisor, employer, or senior psychiatrist | General | 429 | 7.01 | 1.912 | 0.298 | 0.585 | Yes | -1.237 | 497 | NS |

| Emergency | 70 | 7.31 | 1.699 | |||||||

| Reading textbook, guidelines, academic papers | General | 428 | 6.86 | 1.863 | 0.539 | 0.463 | Yes | -1.866 | 496 | NS |

| Emergency | 70 | 7.30 | 1.688 | |||||||

| Visiting an AIH consultation of a senior psychiatrist | General | 428 | 7.29 | 1.884 | 0.612 | 0.434 | Yes | -1.307 | 496 | NS |

| Emergency | 70 | 7.60 | 1.545 | |||||||

| Asking for advice from a senior psychiatrist exhibiting the subject’s information prior to conducting the consultation | General | 429 | 6.56 | 2.038 | 0.483 | 0.487 | Yes | -1.437 | 497 | NS |

| Emergency | 70 | 6.94 | 2.091 | |||||||

| Consulting with the other designated psychiatrist in AIH consultation | General | 429 | 6.01 | 2.277 | 40.508 | 0.034 | No | -.065 | 86.831 | NS |

| Emergency | 70 | 6.03 | 2.621 | |||||||

| Asking for comments from a senior psychiatrist exhibiting them your report after AIH consultation | General | 430 | 6.51 | 2.016 | 0.000 | 0.992 | Yes | -2.163 | 498 | 0.031 |

| Emergency | 70 | 7.07 | 1.958 | |||||||

| Attending a clinical conference with your case after AIH consultation | General | 430 | 6.63 | 1.961 | 10.242 | 0.266 | Yes | -3.167 | 497 | 0.002 |

| Emergency | 69 | 7.42 | 1.666 | |||||||

| Learning through medical treatment of a case subjected to AIH | General | 429 | 6.85 | 2.100 | 0.639 | 0.424 | Yes | -2.380 | 497 | 0.018 |

| Emergency | 70 | 7.49 | 1.808 | |||||||

A questionnaire survey of designated psychiatrists in Japan was conducted to elucidate the current status of AIH consultation education and future needs. As a result, it was revealed that numerous psychiatrists had learned AIH consultation skills through relatively conventional approaches, such as oral education from a supervisor or employer. In addition, most of them emphasized the importance of being involved in the inpatient treatment of hospitalized patients by the governor’s order.

Regarding the representativeness of the data obtained in this survey, we should say that the low response rate limits the reliability of the outcome. Nevertheless, the response rate was not remarkably low for an all-inclusive voluntary survey. While the ratio of public to private psychiatric hospitals in Japan is 1:10, the ratio of respondent’s belonging was approximately 1:2. Therefore, the present data may be biased toward the opinions of psychiatrists working in the public sector. However, since AIH is deemed as a public work in principle, this bias should not cause significant distortions in the results of the analysis.

As mentioned above, there is no structural training course for forensic psychiatrists offered in Japan. However, it does not mean that psychiatrists who are to deal with offenders with mental disorders undergo no training in Japan. They usually acquire risk assessment and management skills through general psychiatric activities such as inpatient treatment in a psychiatric hospital, and general training programs that are not specialized[10]. Considering that psychiatric evaluation is generally based on the clinician’s detailed observation through counseling with the client, a narrative approach for learning assessment skills should be justified. Indeed, designated psychiatrists who have recently been engaged in AIH consultation are more likely to have experienced supervision by senior psychiatrists according to the present study.

Nonetheless, the lack of a standard education protocol for effective assessments in AIH consultations is still a major issue. In this study, most respondents claimed the effectiveness and necessity of official and unofficial seminars as well as learning from textbooks to improve AIH consultation skills. It is broadly believed that forensic fellowships should primarily focus on evaluation and consultations with adequate time, number of patients, and delicate support by a supervisor[11]. In the United States, the primary stream of training of forensic psychiatry was traditionally “on the job”[12]. However, recently, several structured programs for learning forensic psychiatry are established and available for young psychiatrists[13]. In the United Kingdom, training for undergraduate students is also discussed recently, suggesting the challenge of combining theoretical background with teaching practice in this region[14].

The study’s findings also suggest that psychiatrists engaging in emergency psychiatry consider the importance of knowing the course of the case post hospitalization for designated psychiatrists. As they are usually involved in treating patients ordered to be hospitalized by the governor, they may occasionally encounter misjudged cases. Ironically, they occasionally learn how to make appropriate decisions through erroneous cases in forensic mental health settings[15].

Sampling bias represents a significant limitation of this study. We distributed the questionnaire to all psychiatric hospitals across Japan. Typically, individuals with a heightened awareness of the subject matter are more inclined to participate in voluntary surveys such as this. Consequently, there is a potential for the current results to overrepresent responses from individuals possessing expertise or in-depth understanding of forensic psychiatric education. In essence, the average psychiatrist may not perceive the need for it to the same extent as indicated by the results. Addressing this issue and promoting its significance among general psychiatrists pose additional challenges.

A questionnaire survey was conducted to investigate the learning methods utilized for AIH consultations. The study’s findings indicate that many psychiatrists have not undergone structured training specifically tailored for AIH consultations. Instead, narrative approaches with oral teaching remain prevalent in clinical practice among designated psychiatrists. The establishment of a standardized protocol for AIH consultations is urgently needed. Additionally, incorporating feedback from the inpatient treatment section for psychiatrists who have conducted AIH consultations is crucial for enhancing their precise assessment skills. The researchers advocate for the establishment of a comprehensive program package in forensic mental health without delay. Such a program should encompass training in risk assessment skills, opportunities for specialist fellowships involving accompanying consultations with offenders with mental disorders, and collaboration with clinicians working in emergency psychiatric units. The researchers are committed to undertaking further research to develop this program further. Ultimately, it is anticipated that these new programs will be integrated into an official training course administered by the government.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade C

P-Reviewer: Goh KK, Taiwan S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Mullen PE. Forensic mental health. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:307-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ogloff JR, Roesch R, Eaves D. International perspective on forensic mental health systems. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2000;23:429-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Every-Palmer S, Brink J, Chern TP, Choi WK, Hern-Yee JG, Green B, Heffernan E, Johnson SB, Kachaeva M, Shiina A, Walker D, Wu K, Wang X, Mellsop G. Review of psychiatric services to mentally disordered offenders around the Pacific Rim. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2014;6:1-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nakatani Y, Kojimoto M, Matsubara S, Takayanagi I. New legislation for offenders with mental disorders in Japan. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2010;33:7-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shiina A, Sato A, Iyo M, Fujii C. Outcomes of administrative involuntary hospitalization: A national retrospective cohort study in Japan. World J Psychiatry. 2019;9:99-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nishiyama A. Seishin-hoken-ho no kantei to shinsa – Shiteii no tameno riron to jissai. 2nd ed. Tokyo: Shinko Igaku Shuppansha, 1991. |

| 7. | Cerny-Suelzer CA, Ferranti J, Wasser T, Janofsky JS, Michaelsen K, Alonso-Katzowitz JS, Cardasis W, Noffsinger S, Martinez R, Spanggaard M. Practice Resource for Forensic Training in General Psychiatry Residency Programs. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2019;47:S1-S14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marginson S, Mollis M. Comparing national education systems in the global era. 1999. [cited 5 April 2024]. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/3105384/Comparing_national_education_systems_in_the_global_era. |

| 9. | Shiina A. A study of the establishment of the standard and an educational method about medical examination for administrative involuntary hospitalization. Psychiatria et Neurologia Japonica. 2023;125:391-399. |

| 10. | Okita K, Shiina A, Shiraishi T, Watanabe H, Igarashi Y, Iyo M. The Effect of a New Educational Model on the Motivation of Novice Japanese Psychiatrists to enter Forensic Psychiatry. [cited 5 April 2024]. Available from: https://researchmap.jp/shiinaakihiro/published_papers/23018855/attachment_file.pdf. |

| 11. | Michaelsen K, Piel J, Kopelovich S, Reynolds S, Cowley D. A Review of Forensic Fellowship Training: Similar Challenges, Diverse Approaches. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44:149-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hanson CD, Sadoff RL, Sager P, Dent J, Stagliano D. Comprehensive survey of forensic psychiatrists: their training and their practices. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1984;12:403-410. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Frierson RL. Examining the Past and Advocating for the Future of Forensic Psychiatry Training. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48:16-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sharda L, Wright K. A critical review of undergraduate education and teaching in forensic psychiatry. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2023;33:401-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shiina A, Fujisaki M, Nagata T, Oda Y, Suzuki M, Yoshizawa M, Iyo M, Igarashi Y. Expert consensus on hospitalization for assessment: a survey in Japan for a new forensic mental health system. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2011;10:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |