Published online May 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i5.715

Revised: April 10, 2024

Accepted: April 17, 2024

Published online: May 19, 2024

Processing time: 110 Days and 14.5 Hours

Psychological distress, especially depression, associated with perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease (PFCD) is widespread and refractory. However, there is a sur

To estimate the prevalence of depressive symptoms and investigate the de

The study was conducted in the form of survey and clinical data collection via questionnaire and specialized medical staff. Depressive symptoms, life quality, and fatigue severity of patients with PFCD were assessed by Patient Health Questionnaire-9, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patient Quality of Life Ques

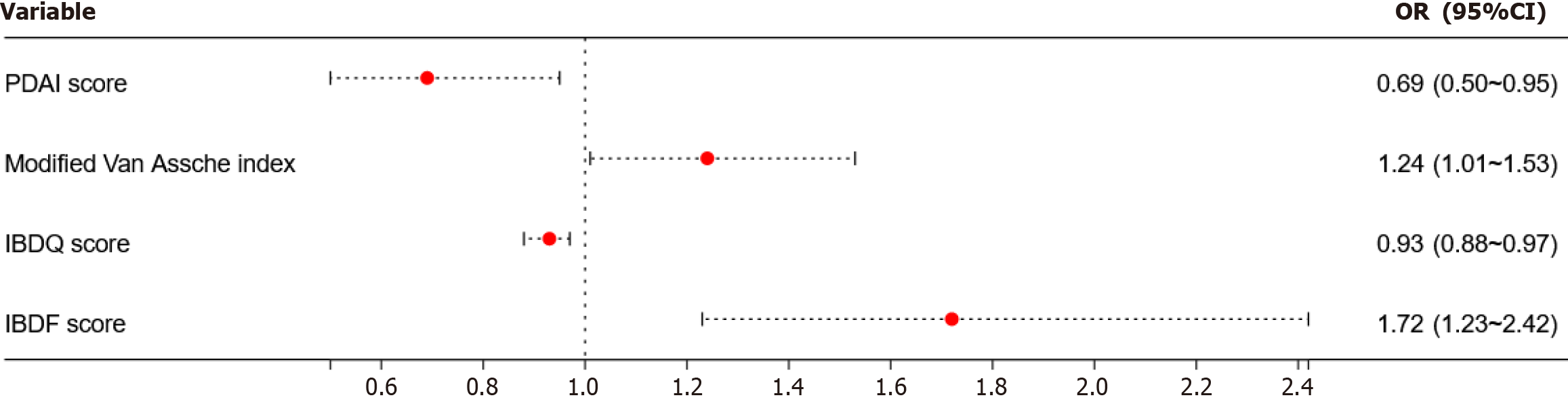

A total of 123 patients with PFCD were involved, and 56.91% were suffering from depression. According to multivariate logistic regression analysis, Perianal Disease Activity Index (PDAI) score [odds ratio (OR) = 0.69, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.50 to 0.95], IBDQ score (OR = 0.93, 95%CI: 0.88 to 0.97), modified Van Assche index (OR = 1.24, 95%CI: 1.01 to 1.53), and IBD Fatigue score (OR = 1.72, 95%CI: 1.23 to 2.42) were independent risk factors of depression-related prevalence among patients with PFCD (P < 0.05). Multiple linear regression analysis revealed that the increasing perianal modified Van Assche index (β value = 0.166, 95%CI: 0.02 to 0.31) and decreasing IBDQ score (β value = -0.116, 95%CI: -0.14 to -0.09) were independently associated with the severity of depression (P < 0.05).

Depressive symptoms in PFCD patients have significantly high prevalence. PDAI score, modified Van Assche index, quality of life, and fatigue severity were the main independent risk factors.

Core Tip: Perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease (PFCD) is the most prominent, invasive and common lesion among the phenotypes of Crohn’s disease (CD). Due to the unique disease experience of PFCD patients, they suffer from severe clinical and psychological consequences like depression. However, there is a lack of studies focusing on the risk factors of depression within specific disease types of CD. In this study, we analyzed the prevalence and risk factors of PFCD with depression, which could assist professionals in early identification and medical intervention in patients with PFCD.

- Citation: Li J, Ng WY, Qiao LC, Yuan F, Lan X, Zhu LB, Yang BL, Wang ZQ. Prevalence and risk factors of depression among patients with perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(5): 715-725

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i5/715.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i5.715

Crohn’s disease (CD), one of the main inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) types, is characterized by chronic nonspecific intestinal inflammation. The clinical features of CD, such as severe symptoms, complex complications, and chronic recurrent state without spontaneous healing, are significant enormous challenges to the physical and mental health of CD patients, who are more likely to be psychologically impaired. As reported by the newest systematic review, the composite morbidity of depressive symptoms in CD patients was around 25.3%[1], which is two to four times greater than the general population, with an approximate incidence rate of 6%[2].

China and other parts of Asia display a higher prevalence of perianal CD, which is one of the most challenging phe

A study conducted by Mahadev et al[6] showed that 73% of PFCD patients were experiencing symptoms of depression. Remarkably, 13% of those had a strong tendency to suicide and were even willing to trade their lifespan (over 10%) for PFCD relief. To further investigate the prevalence of depression in CD patients, there was a cohort study[7] regarding perianal lesions as essential predictors of CD patients with depression. The prevalence of perianal lesions in CD patients with depression was almost two-fold greater than in patients without CD.

Another investigation[8] demonstrated that perianal lesions were the main factor of both depression and anxiety. In addition, CD patients with depressive and anxiety disorder comorbidities had a triple occurrence rate of perianal lesions and surgical procedure rate in comparison with the CD patients without the above psychological disorders. Moreover, a notable relationship was noted between psychological diseases and CD[9]. The link possesses the possibility of CD exacerbations or other complications, therefore aggravating the healthcare-related economic burden. Thus, it is im

Psychological disorders in IBD were shown to be independently associated with female sex, disease activity, and ostomy in previous research[10,11]. However, there is a scarcity of analogous studies focusing on specific disease types of IBD. In contrast to general CD patients, those with perianal lesions experience distinct and additional symptoms that substantially alter their disease experience. Furthermore, research on the factors of depression in this specific subset of PFCD patients is limited at present. In short, we conducted a cross-sectional study to screen the depressive symptoms of PFCD patients and examined the related clinical factors to determine the research deficiencies of IBD-related psychological issues.

Patients with PFCD who were admitted to the anorectal ward of the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine and diagnosed by perianal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) during the period from September 2022 to September 2023 were included in this study consecutively. Prior to the enrollment, written informed consent was obtained from the subjects or their legal guardians. The study was approved by the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (Approval No. 2020NL-170-02).

Patients were considered for enrollment if they fit the following inclusion criteria: (1) Diagnosed by perianal MRI; (2) age between 16 years and 60 years; (3) minimum 6 years of education; and (4) basic reading and cell phone operation skills. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Diagnosed with psychiatric disorders explicitly; (2) unable to understand the content in the questionnaire; (3) clinical data missing and not being able to be communicate; and (4) without any perianal MRI examination.

In our study, data collection, including demographic and clinical information, was conducted by a questionnaire and professional IBD medical staff. All data were collected and organized within 1 wk of admission to the anorectal ward.

The following information was gathered through a uniform questionnaire: (1) Basic demographic information in

PHQ-9: Our study utilized the PHQ-9 as a tool for evaluating the depressive symptoms of PFCD patients. The scale is a nine-item self-reported questionnaire and has emerged as the most dependable tool for detecting depression[12] because of its perfect sensitivity and specificity[13]. The scoring system of the PHQ-9 is as follows: Scores of 0-4 correspond to the absence of depression; scores of 5-9 correspond to mild depression; scores of 10-14 correspond to moderate depression; scores of 15-19 correspond to moderately severe depression; and scores of 20-27 correspond to severe depression.

IBDQ: We used the Chinese version of IBDQ to evaluate the quality of life among PFCD patients. This assessment encompasses not only gastrointestinal symptoms but also constitutional symptoms, social functioning, and emotional state. The total score of the IBDQ ranges from 32 to 224, with higher scores indicating a higher quality of life. The questionnaire demonstrated adequate validity and reliability[14].

IBD-F patient self-assessment scale: Czuber-Dochan et al[15] invented a self-assessment scale for IBD patients, which has good reliability and validity, and can be used as an initial screening tool for fatigue in IBD patients. The first part of the Chinese version of the IBD-F scale was used in this study to assess the level of fatigue in PFCD patients. The relevant scale in our study is as follows: No fatigue (0 points); mild to moderate fatigue (1-10 points); and severe fatigue (11-20 points).

Modified van assche index: This study applied the perianal modified Van Assche index to objectively quantify the disease activity of fistulizing inflammation. In 2017, Samaan et al[16] amended the original Van Assche index[17], detailed the standardized score definition in each entry item, and improved the inter-rater reliability. The score was evaluated by two or more radiologists specializing in the field of proctology in our study. A higher total score indicated a more severe perianal inflammatory activity.

The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 26.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). The mea

A logistic regression model was utilized to conduct a multivariate analysis. The outcomes were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Variables with P values < 0.10 in the univariate analysis were further analyzed in the multivariate analysis. The factors that showed statistical significance in the multivariate analysis were further subjected to Spearman rank correlation analysis to examine the relationship between the severity of depression and those variables. Furthermore, multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to ascertain the potential relationship between the demographic and clinical features of the cohort and the severity of depression.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Jun-Qin Wang from the Department of Public Health, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine.

This research comprised a cohort of 123 PFCD patients eligible for enrollment. Of these patients, 85 (69.11%) were male and 38 (30.89%) were female. The age of the patients ranged from 16 years to 59 years, with a mean age of 28.55 ± 9.18 years. Almost one-third were married (36.59%), had a high school education or above (69.93%), and were employed (59.35%). An average CD duration of 4.26 ± 4.70 years and an average PFCD duration of 6.00 ± 23.00 months were shown. The majority of the lesions were located in the ileum (42.28%) among the study population, and 71.54% of the population used biologics. More detailed demographic data and clinical features are summarized in Table 1.

| Variable | Cohort, n = 123 | Without depression, n = 53 | With depression, n = 70 | P value |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Female sex | 38 (30.89) | 12 (22.64) | 26 (37.14) | 0.115 |

| Age in yr | 28.55 ± 9.18 | 28.51 ± 9.17 | 28.59 ± 9.26 | 0.964 |

| BMI in kg/m2 | 21.02 ± 3.85 | 21.56 ± 3.80 | 20.60 ± 3.86 | 0.175 |

| Smoker | 9 (7.32) | 1 (1.89) | 8 (11.43) | 0.076 |

| High school or above | 86 (69.93) | 41 (77.36) | 45 (64.29) | 0.164 |

| Married | 45 (36.59) | 20 (37.74) | 25 (35.71) | 0.852 |

| Procreated | 38 (30.89) | 15 (28.30) | 23 (32.86) | 0.694 |

| Currently employed | 73 (59.35) | 32 (60.38) | 41 (58.57) | 0.855 |

| Low-income population as ≤ 3.6 million yuan | 61 (49.59) | 27 (50.94) | 34 (48.57) | 0.856 |

| Overall clinical characteristics | ||||

| CD course in yr | 4.26 ± 4.70 | 3.90 ± 4.10 | 4.53 ± 5.11 | 0.465 |

| CD phenotypes | ||||

| L1-Terminal ileum | 52 (42.28) | 25 (47.17) | 27 (38.57) | 0.362 |

| L2-Colon | 33 (26.83) | 16 (30.19) | 17 (24.29) | 0.539 |

| L3-Ileum and colon | 38 (30.89) | 12 (22.64) | 26 (37.14) | 0.115 |

| B2-Stricturing | 39 (31.71) | 18 (33.96) | 21 (30.00) | 0.698 |

| B3-Penetrating | 3 (2.44) | 2 (3.77) | 1 (1.43) | 0.577 |

| CDAI score, median ± IQR | 98.77 ± 119.39 | 46.67 ± 82.04 | 130.20 ± 99.21 | 0.000 |

| History of gastrointestinal surgery | 18 (14.63) | 6 (11.32) | 12 (17.14) | 0.445 |

| History of ostomy | 8 (6.50) | 5 (9.43) | 3 (4.29) | 0.289 |

| Laboratory indicators, median ± IQR | ||||

| ESR in mm/h | 23.00 ± 29.00 | 14.00 ± 22.00 | 34.00 ± 39.00 | 0.000 |

| CRP in mg/L | 7.96 ± 17.80 | 5.72 ± 11.57 | 10.20 ± 25.47 | 0.004 |

| FC in µg/g | 732.80 ± 1128.30 | 374.20 ± 845.00 | 836.90 ± 1414.95 | 0.001 |

| Current medication | ||||

| Biologics therapy | 88 (71.54) | 35 (66.04) | 53 (75.71) | 0.313 |

| Immunomodulator therapy | 26 (21.14) | 8 (15.09) | 18 (25.71) | 0.184 |

| Corticosteroid therapy | 15 (12.20) | 5 (9.43) | 10 (14.29) | 0.580 |

| Perianal clinical characteristics | ||||

| PFCD course in month, median ± IQR | 6.00 ± 23.00 | 5.00 ± 24.00 | 7.50 ± 28.00 | 0.146 |

| History of perianal surgery of ≥ 2 | 57 | 24 | 33 | 0.857 |

| PDAI score, median ± IQR | 6.00 ± 5.00 | 4.50 ± 5.00 | 6.00 ± 5.00 | 0.001 |

| Wexner score, median ± IQR | 2.00 ± 7.00 | 1.00 ± 4.00 | 4.50 ± 7.00 | 0.001 |

| Modified Van Assche index, median ± IQR | 12.00 ± 8.00 | 8.00 ± 11.00 | 13.00 ± 5.00 | 0.000 |

| Physiological and psychological characteristics | ||||

| IBDQ score, median ± IQR | 172 ± 50 | 194 ± 27 | 152 ± 37 | 0.000 |

| IBD-F score, median ± IQR | 6.00 ± 5.00 | 4.00 ± 5.00 | 8.00 ± 4.00 | 0.000 |

As for the depression levels among 123 participants, 70 of them displayed depressive symptoms. To be specific, 53 patients exhibited mild depression (43.09%), 6 patients exhibited moderate depression (4.88%), 8 patients exhibited moderately severe depression (6.50%), and 3 patients exhibited severe depression (2.44%) (Table 2).

| Clinical characteristic | No depression | Mild depression | Moderate depression | Moderately severe depression | Severe depression |

| PFCD | 53 (43.09) | 53 (43.09) | 6 (4.88) | 8 (6.50) | 3 (2.44) |

Univariate analysis: The patients with PFCD were categorized into two groups: Those with depression and those without depression. The analysis of clinical data of both groups of patients showed that the use of ESR, CRP, FC, CDAI score, PDAI score, Wexner score, modified Van Assche index, IBDQ score, and IBD-F score between the depressive group and the non-depressive group had significant statistical differences (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis: The possible factors (variables which adhered to P < 0.10 in Table 1) related to depressive symptoms were screened, and a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed. The most obvious finding to emerge from this analysis was that the modified Van Assche index (OR = 1.24, 95%CI: 1.01 to 1.53), PDAI score (OR = 0.69, 95%CI: 0.50 to 0.95), IBDQ score (OR = 0.93, 95%CI: 0.88 to 0.97), and IBD-F score (OR = 1.72, 95%CI: 1.23 to 2.42) significantly influenced the prevalence of depression (P < 0.05) (Table 3 and Figure 1).

| Factor | β value | Wald value | P value | OR value | 95%CI |

| Smoker | 1.111 | 0.36 | 0.550 | 3.04 | 0.08 to 116.33 |

| CDAI score | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.957 | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.02 |

| ESR in mm/h | 0.029 | 2.20 | 0.138 | 1.03 | 0.99 to 1.07 |

| CRP in mg/L | -0.030 | 1.28 | 0.258 | 0.97 | 0.92 to 1.02 |

| FC in µg/g | 0.001 | 3.17 | 0.075 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 |

| PDAI score | -0.373 | 5.03 | 0.025 | 0.69 | 0.50 to 0.95 |

| Wexner score | 0.020 | 0.04 | 0.850 | 1.02 | 0.83 to 1.26 |

| Modified Van Assche index | 0.218 | 4.37 | 0.037 | 1.24 | 1.01 to 1.53 |

| IBDQ score | -0.076 | 9.73 | 0.002 | 0.93 | 0.88 to 0.97 |

| IBD-F score | 0.545 | 10.02 | 0.002 | 1.72 | 1.23 to 2.42 |

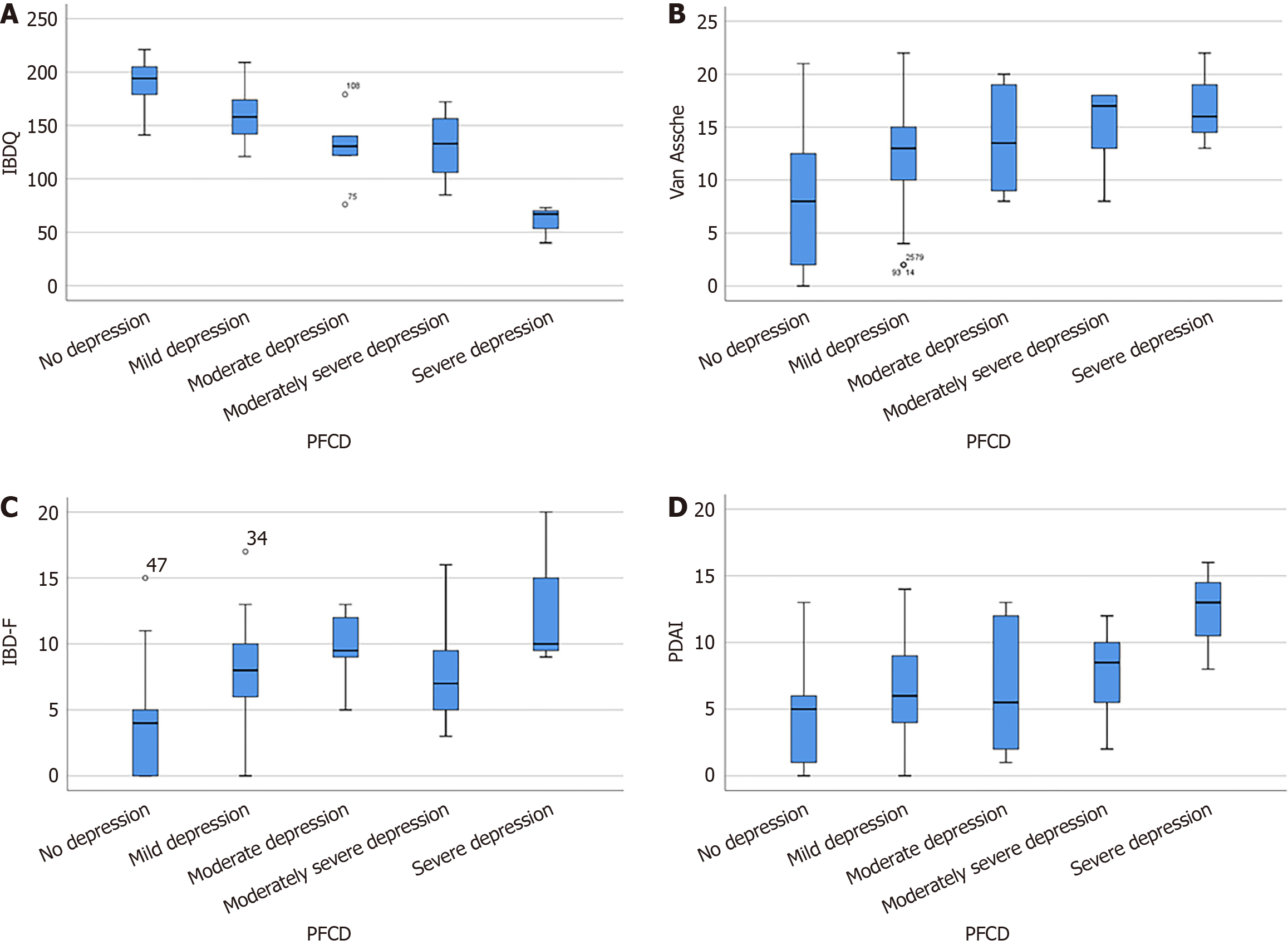

Spearman rank correlation analysis: The PDAI score, IBDQ score, perineal modified Van Assche index, IBD-F score, and the severity of depression were analyzed using Spearman rank correlation analysis. The analysis showed the following conclusions: (1) A lower IBDQ score was associated with more severe depression (r = -0.711, P = 0.000); (2) a higher modified Van Assche score was associated with more severe depression (r = 0.466, P = 0.000); (3) a higher IBD-F score was associated with more severe depression (r = 0.593, P = 0.000); and (4) a higher PDAI score was associated with more severe depression (r = 0.333, P = 0.000). The relationship between depressive level and the above variables was presented using box plots (Figure 2).

Multiple linear regression analysis: The increased modified Van Assche score (β value = 0.166, 95%CI: 0.02 to 0.31) and the decreased IBDQ score (β value = -0.116, 95%CI: -0.14 to -0.09) were independently associated with the severity of depression. These factors explained the variance of 65.0% (Table 4).

| Factor | β value | t value | P value | 95%CI | R2 |

| Smoker | 0.124 | 0.09 | 0.928 | -2.58 to 2.83 | 0.650 |

| CD activity index | 0.006 | 0.96 | 0.341 | -0.01 to 0.02 | |

| ESR in mm/h | 0.005 | 0.25 | 0.804 | -0.03 to 0.04 | |

| CRP in mg/L | -0.006 | -0.32 | 0.746 | -0.04 to 0.03 | |

| FC in µg/g | 0.000 | 0.78 | 0.440 | 0.00 to 0.00 | |

| PDAI score | -0.134 | -1.06 | 0.292 | -0.39 to 0.12 | |

| Wexner score | -0.069 | -0.88 | 0.380 | -0.23 to 0.09 | |

| Modified Van Assche index | 0.166 | 2.22 | 0.028 | 0.02 to 0.31 | |

| IBDQ score | -0.116 | -8.58 | 0.000 | -0.14 to -0.09 | |

| IBD-F score | 0.169 | 1.61 | 0.109 | -0.04 to 0.38 |

Our cross-sectional study revealed a significant prevalence of depressive symptoms among PFCD patients in which 56.91% of them were in distress. It is noteworthy that even 13.82% of them exhibited moderate to severe levels of depression. Risk factors of depression in CD patients were shown to be linked with the activity of perianal lesions, quality of life, and fatigue. To the best of our knowledge, this study was one of the few studies about the prevalence of depression among PFCD patients and the related factors. Furthermore, our analysis encompassed various variables that might be directly associated with depression, including the course of perianal lesions, frequency of perianal surgeries, the modified Van Assche score, quality of life, and fatigue. Notably, unique characteristics of the perianal condition were examined infrequently in prior studies.

The prevalence of depressive symptoms was markedly greater in patients with PFCD compared to those with typical CD and IBD. Two meta-analyses[1,11] determined that the occurrence rate of depressive symptoms in IBD patients was around 25.2% and 21.6%, respectively. Likewise, the occurrence rate of depression in CD patients varied from 17.5% in a survey based on a primary care database in the United Kingdom to 41.7% in a different study that examined a population-based group[18,19]. The existing findings on the prevalence of depression in IBD were still multiform. It might be attributed to factors such as sample size, geographical and age disparities within the study population, and the selection of the depressive rating scale.

The findings of our study exhibited a notable increase compared to the prior studies. This distinction may be due to the fact that our investigation specifically focused on PFCD. Patients with PFCD exhibit diverse disease manifestations compared to those without perianal fistulas. They suffer from challenging therapeutic dilemmas and alterations of body image and living habits, exacerbating life quality and psychological consequences due to persistent defecation, suppuration, pain, infection, and impairments in the sphincter and perineal tissues. In addition, this discrepancy could be linked to the different applications of psychological assessment instruments. When comparing with the structured diagnostic interviews (gold standard clinical diagnosis) of depression, there was a possibility of overestimating symptoms referred to the PHQ-9 self-reported scale. Nevertheless, our study revealed a significant prevalence of depressive symptoms in CD patients, particularly in a specific subset of patients with PFCD, where mental health issues play a crucial role.

Previous literature had reported a higher occurrence rate of depression among patients in active CD state compared to those in remission state[20], and the overall increased disease activity was independently associated with the deve

A case-control study including more than 1300 patients revealed that perianal disease was a significant risk factor for anxiety and depression in patients with IBD[7]. Another investigation also documented that history of perianal disease was the major risk factor for anxiety and depression in CD patients[8]. Not surprisingly, all of the studies mentioned above involved perianal disease history as their experimental criteria without quantifying the perianal disease activity. Our present study utilized two quantitative indicators for evaluating perianal fistulizing activity and the modified Van Assche score, which expressed the existence of a correlation between perianal activity and depression. Higher perianal inflammatory activity is associated with more complex fistulas, more secretions, swelling, and pain and is accompanied by an uncomfortable sitting posture, unpleasant odor, low self-esteem, and feelings of embarrassment, thus increasing the risk of depression. In order to detect depressive disorder in PFCD patients, physicians should go beyond laboratory parameters in clinical practice since inflammatory markers that react to disease activity do not correlate with depression. Perianal MRI is particularly important.

CD patients with perianal comorbidities such as perianal abscesses and fistulas have a lower quality of life than the general population[23]. The delayed healing and intractable nature of PFCD means that patients often experience uncomfortable symptoms and the impacts of repeated surgeries, disrupting their daily life, relationships, social participation, and psychological well-being, which may lead to a lower quality of life. In this study, we found that the life quality of PFCD patients with depressive symptoms was lower than that of those without depressive symptoms. This is similar to the findings of García-Alanís et al[24].

In the multivariate regression analysis, a reduction in quality of life was significantly associated with the presence and severity of depression. A lower IBDQ score was associated with a more severe depression. Geiss et al[21] reported a strong correlation between life quality and PHQ-9 score among IBD patients. The IBDQ score used in this research incorporated the impact of the disease on psychological functioning and, to some extent, overlapped with patients’ psychoemotional evaluations, which may partly explain the stronger correlation between life quality and depression. Poor quality of life will aggravate psychological distress, such as anxiety and depression, in patients with IBD[25]. A lower quality of life is manifested in anxiety about the loss of bowel control, worry about systemic symptoms, fear of socialization, stress from not being able to work and study normally, and a lack of confidence in body image, which will contribute to an increasing risk of depression.

Fatigue coexists with psychosomatic problems such as depression and anxiety in chronic conditions[26,27], including IBD[28]. Our findings suggested that fatigue was significantly associated with the presence of depression in PFCD, which might have the same behavioral, emotional, and cognitive characteristics. The main symptom of fatigue is a lack of energy or persistent tiredness that is disproportionate to physical exertion, limiting daily activities, and not being able to be relieved by rest[29]. CD patients have a higher prevalence of fatigue[30]. They describe fatigue as one of the most bothersome symptoms[31] and may even be more debilitating and depressing than CD symptoms. This trouble severely affects patient quality of life and reduces labor productivity. Jonefjäll et al[32] found that fatigue could have a negative psychological impact on IBD patients, exacerbating clinical symptoms and promoting disease progression. Another study also showed that concurrent depression was the most substantial risk factor of IBD with fatigue[33]. These findings complement our results and suggest that there may be complex interactions and interdependencies between depression and fatigue.

Age, smoking history, education level, marital status, annual income, and related medication were not associated with depression in PFCD according to our research. Being female had been reported as a predictor of depression in patients with IBD in several papers[34,35], and previous abdominal surgeries and ostomy had also been reported to be associated with depression in perianal CD patients[6]. Our findings, however, did not show any significant association between depression and sex or abdominal surgery treatment. This might be related to the small sample size and heterogeneity of participants in our study.

We included, for the first time, three parameters regarding the characteristics of perianal disease, namely the PFCD course, the number of perianal surgeries and the Wexner score, which can reflect the chronic course and severity of anal fistula in patients. However, we were puzzled when the three perianal parameters did not significantly intensify depression as we had hypothesized they would, and the longer intervals between fistula recurrences and surgeries might overestimate the duration of PFCD and the number of perianal surgeries. In addition, the overall Wexner score was low, and anal incontinence was not that critical in our study population.

Our analyses had some limitations. First, the sample size of our study was relatively small. Further extensive sample size studies are necessary to screen for the prevalence of depression in PFCD patients more accurately and to identify risk further factors for depression. Second, the IBDQ was used in this study to assess the overall quality of life of CD patients, but it did not allow for a comprehensive assessment of the impact of fistula. The Crohn’s Anal Fistula Quality of Life scale[36] is a brand-new measurement tool for complex PFCD. In the future, we can use it to evaluate the quality of life of PFCD patients, and the results may be more meaningful. Furthermore, none of the patients enrolled in this study underwent antidepressant psychotherapy although they were exhibiting diverse levels of depressive symptoms. This condition could potentially stem from the limited awareness of depression associated with PFCD among medical professionals and patients. Moving forward, we are committed to broadening our research scope and conducting comparative analyses on the alterations in prior and post antidepressant therapy, thereby enhancing the specificity of our study. Finally, there may be an interconnection between depression, quality of life, and fatigue, necessitating further studies to test causal and more complex models of depression related to PFCD.

In conclusion, our study suggested that patients with PFCD had a higher prevalence of depression, and the related risk factors of depression included the PDAI score, the modified Van Assche score, quality of life, and fatigue. The above suggestion may help physicians to emphasize, accurately identify, and encourage high-risk groups for psychological disorders, thus alleviating patients’ symptoms and improving quality of life and prognosis.

The authors would like to thank the members of the Department of Radiology and the Department of Colorectal Surgery, Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine for their technical support. The authors also thank Jun-Qin Wang for her biostatistics assistance.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Matsui T, Japan S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Neuendorf R, Harding A, Stello N, Hanes D, Wahbeh H. Depression and anxiety in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2016;87:70-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 448] [Cited by in RCA: 403] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet. 2018;392:2299-2312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1255] [Cited by in RCA: 2527] [Article Influence: 361.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Singh B, McC Mortensen NJ, Jewell DP, George B. Perianal Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 2004;91:801-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rackovsky O, Hirten R, Ungaro R, Colombel JF. Clinical updates on perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12:597-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Panés J, Rimola J. Perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease: pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:652-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mahadev S, Young JM, Selby W, Solomon MJ. Self-reported depressive symptoms and suicidal feelings in perianal Crohn's disease. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:331-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ananthakrishnan AN, Gainer VS, Cai T, Perez RG, Cheng SC, Savova G, Chen P, Szolovits P, Xia Z, De Jager PL, Shaw S, Churchill S, Karlson EW, Kohane I, Perlis RH, Plenge RM, Murphy SN, Liao KP. Similar risk of depression and anxiety following surgery or hospitalization for Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:594-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Maconi G, Gridavilla D, Viganò C, Sciurti R, Asthana AK, Furfaro F, Re F, Ardizzone S, Ba G. Perianal disease is associated with psychiatric co-morbidity in Crohn's disease in remission. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1285-1290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Bozada Gutiérrez KE, Sarmiento-Aguilar A, Fresán-Orellana A, Arguelles-Castro P, García-Alanis M. Depression and Anxiety Disorders Impact in the Quality of Life of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Psychiatry J. 2021;2021:5540786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sceats LA, Dehghan MS, Rumer KK, Trickey A, Morris AM, Kin C. Surgery, stomas, and anxiety and depression in inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective cohort analysis of privately insured patients. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:544-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Barberio B, Zamani M, Black CJ, Savarino EV, Ford AC. Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:359-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 99.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;365:l1476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 632] [Cited by in RCA: 968] [Article Influence: 161.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Costantini L, Pasquarella C, Odone A, Colucci ME, Costanza A, Serafini G, Aguglia A, Belvederi Murri M, Brakoulias V, Amore M, Ghaemi SN, Amerio A. Screening for depression in primary care with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:473-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 413] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 90.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zavala-Solares MR, Salazar-Salas L, Yamamoto-Furusho JK. Validity and reliability of the health-related questionnaire IBDQ-32 in Mexican patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:711-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Czuber-Dochan W, Norton C, Bassett P, Berliner S, Bredin F, Darvell M, Forbes A, Gay M, Nathan I, Ream E, Terry H. Development and psychometric testing of inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) patient self-assessment scale. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1398-1406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Samaan MA, Puylaert CAJ, Levesque BG, Zou GY, Stitt L, Taylor SA, Shackelton LM, Vandervoort MK, Khanna R, Santillan C, Rimola J, Hindryckx P, Nio CY, Sandborn WJ, D'Haens G, Feagan BG, Jairath V, Stoker J. The development of a magnetic resonance imaging index for fistulising Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:516-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Van Assche G, Vanbeckevoort D, Bielen D, Coremans G, Aerden I, Noman M, D'Hoore A, Penninckx F, Marchal G, Cornillie F, Rutgeerts P. Magnetic resonance imaging of the effects of infliximab on perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:332-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Irving P, Barrett K, Nijher M, de Lusignan S. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in people with inflammatory bowel disease and associated healthcare use: population-based cohort study. Evid Based Ment Health. 2021;24:102-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Facanali CBG, Sobrado Junior CW, Fraguas Junior R, Facanali Junior MR, Boarini LR, Sobrado LF, Cecconello I. The relationship of major depressive disorder with Crohn's disease activity. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2023;78:100188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mikocka-Walus A, Knowles SR, Keefer L, Graff L. Controversies Revisited: A Systematic Review of the Comorbidity of Depression and Anxiety with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:752-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 448] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Geiss T, Schaefert RM, Berens S, Hoffmann P, Gauss A. Risk of depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Dig Dis. 2018;19:456-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gao X, Tang Y, Lei N, Luo Y, Chen P, Liang C, Duan S, Zhang Y. Symptoms of anxiety/depression is associated with more aggressive inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gao N, Qiao Z, Yan S, Zhu L. Evaluation of health-related quality of life and influencing factors in patients with Crohn disease. J Int Med Res. 2022;50:3000605221098868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | García-Alanís M, Quiroz-Casian L, Castañeda-González H, Arguelles-Castro P, Toapanta-Yanchapaxi L, Chiquete-Anaya E, Sarmiento-Aguilar A, Bozada-Gutiérrez K, Yamamoto-Furusho JK. Prevalence of mental disorder and impact on quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:206-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mitropoulou MA, Fradelos EC, Lee KY, Malli F, Tsaras K, Christodoulou NG, Papathanasiou IV. Quality of Life in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Importance of Psychological Symptoms. Cureus. 2022;14:e28502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ormstad H, Simonsen CS, Broch L, Maes DM, Anderson G, Celius EG. Chronic fatigue and depression due to multiple sclerosis: Immune-inflammatory pathways, tryptophan catabolites and the gut-brain axis as possible shared pathways. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;46:102533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sibbritt D, Bayes J, Peng W, Maguire J, Adams J. Associations Between Fatigue and Disability, Depression, Health-Related Hardiness and Quality of Life in People with Stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2022;31:106543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chavarría C, Casanova MJ, Chaparro M, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Ezquiaga E, Bujanda L, Rivero M, Argüelles-Arias F, Martín-Arranz MD, Martínez-Montiel MP, Valls M, Ferreiro-Iglesias R, Llaó J, Moraleja-Yudego I, Casellas F, Antolín-Melero B, Cortés X, Plaza R, Pineda JR, Navarro-Llavat M, García-López S, Robledo-Andrés P, Marín-Jiménez I, García-Sánchez V, Merino O, Algaba A, Arribas-López MR, Banales JM, Castro B, Castro-Laria L, Honrubia R, Almela P, Gisbert JP. Prevalence and Factors Associated With Fatigue in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Multicentre Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:996-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gong SS, Fan YH, Lv B, Zhang MQ, Xu Y, Zhao J. Fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Eastern China. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:1076-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | D'Silva A, Fox DE, Nasser Y, Vallance JK, Quinn RR, Ronksley PE, Raman M. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Fatigue in Adults With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:995-1009.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wåhlin M, Stjernman H, Munck B. Disease-Related Worries in Persons With Crohn Disease: An Interview Study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2019;42:435-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jonefjäll B, Simrén M, Lasson A, Öhman L, Strid H. Psychological distress, iron deficiency, active disease and female gender are independent risk factors for fatigue in patients with ulcerative colitis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:148-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Uhlir V, Stallmach A, Grunert PC. Fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease-strongly influenced by depression and not identifiable through laboratory testing: a cross-sectional survey study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Panara AJ, Yarur AJ, Rieders B, Proksell S, Deshpande AR, Abreu MT, Sussman DA. The incidence and risk factors for developing depression after being diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:802-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Navabi S, Gorrepati VS, Yadav S, Chintanaboina J, Maher S, Demuth P, Stern B, Stuart A, Tinsley A, Clarke K, Williams ED, Coates MD. Influences and Impact of Anxiety and Depression in the Setting of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2303-2308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Adegbola SO, Dibley L, Sahnan K, Wade T, Verjee A, Sawyer R, Mannick S, McCluskey D, Bassett P, Yassin N, Warusavitarne J, Faiz O, Phillips R, Tozer PJ, Norton C, Hart AL. Development and initial psychometric validation of a patient-reported outcome measure for Crohn's perianal fistula: the Crohn's Anal Fistula Quality of Life (CAF-QoL) scale. Gut. 2021;70:1649-1656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |