Published online May 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i5.686

Revised: February 20, 2024

Accepted: March 29, 2024

Published online: May 19, 2024

Processing time: 112 Days and 3 Hours

Insomnia is among the most common sleep disorders worldwide. Insomnia in older adults is a social and public health problem. Insomnia affects the physical and mental health of elderly hospitalized patients and can aggravate or induce physical illnesses. Understanding subjective feelings and providing reasonable and standardized care for elderly hospitalized patients with insomnia are urgent issues.

To explore the differences in self-reported outcomes associated with insomnia among elderly hospitalized patients.

One hundred patients admitted to the geriatric unit of our hospital between June 2021 and December 2021 were included in this study. Self-reported symptoms were assessed using the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS), Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7), Geriatric Depression Scale-15 (GDS-15), Memorial University of Newfoundland Scale of Happiness (MUNSH), Barthel Index Evaluation (BI), Morse Fall Scale (MFS), Mini-Mental State Examination, and the Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36). Correlation coefficients were used to analyze the correlation between sleep quality and self-reported symptoms. Effects of insomnia was analyzed using Logistic regression analysis.

Nineteen patients with AIS ≥ 6 were included in the insomnia group, and the incidence of insomnia was 19% (19/100). The remaining 81 patients were assigned to the non-insomnia group. There were significant differences between the two groups in the GDA-7, GDS-15, MUNSH, BI, MFS, and SF-36 items (P < 0.05). Patients in the insomnia group were more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and other mental illnesses, as well as difficulties with everyday tasks and a greater risk of falling (P < 0.05). Subjective well-being and quality of life were poorer in the insomnia group than in the control group. The AIS scores positively correlated with the GAD-7, GDS-15, and MFS scores in elderly hospitalized patients with insomnia (P < 0.05). Logistic regression analysis showed that GDS-15 ≥ 5 was an independent risk factor for insomnia in elderly hospitalized patients (P < 0.05).

The number of self-reported symptoms was higher among elderly hospitalized patients with insomnia. Therefore, we should focus on the main complaints of patients to meet their care needs.

Core Tip: Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 100 elderly hospitalized patients. Elderly hospitalized patients had higher rates of insomnia symptoms. Insomnia in elderly hospitalized patients positively correlated with anxiety, depression, and fall risk. Depression was also found to be an independent risk factor for insomnia in elderly hospitalized patients.

- Citation: Ding X, Qi LX, Sun DY. Differences in insomnia-related self-reported outcomes among elderly hospitalized patients. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(5): 686-694

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i5/686.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i5.686

According to the seventh national population census conducted in 2020, there were 264.02 million people, 60 years of age or older in China, making up 18.70% of the total population, and this proportion is only expected to grow. An important part of building a "Healthy China" is ensuring that the older population is cared for, both physically and psychologically, and that their quality of life is enhanced. Insomnia, a common sleep disorder in older adults, not only increases the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases, but also damages physical and mental health (MH)[1-3]. Insomnia may exacerbate pre-existing conditions in elderly hospitalized patients and severely reduce their quality of life. It is an important part of clinical nursing work to focus on and improve the quality of sleep of elderly hospitalized patients.

Recently, an increasing number of researchers have acknowledged that patients should play an active role in managing their own health[4]. The study of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) originated in the 1970s and refers to health-related information obtained directly from patients without any interpretation by others[5]. PROs may be gathered via patient interviews and questionnaires, with patients’ subjective experiences being used as a foundation for evaluating symptoms, and self-reported indicators of disease and treatment outcomes such as symptom burden, psychological sentiments, functional status, quality of life, and others are the major focus of the assessment[6]. Self-reported outcome measurements from patients considerably enhance treatment quality and comfort[7,8]. Therefore, this study applied PROs to elderly hospitalized patients, aiming to understand the variations in insomnia-related self-reported outcomes of these patients and provide a theoretical foundation for implementing precision care.

One hundred elderly hospitalized patients in the geriatric department of our hospital were selected for face-to-face interviews between June 2021 and December 2021. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age ≥ 60 years old, with good orientation to time, place, and people; (2) able to communicate verbally; and (3) volunteered to participate in this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Severe sleep-affecting diseases, (2) major personal or family events in the past 2 months, and (3) severe cognitive impairment or inability to self-report outcomes. There were 57 males (57%) and 43 females (43%), with an average age of 71.8 ± 7.17 years. This study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee (No. 2021-K058-01), and all participants signed an informed consent form.

A self-designed scale was used in the general information questionnaire to examine the general situation of elderly patients, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), place of residence, living arrangements, monthly income, marital status, level of education, occupation, smoking, drinking, and physical activity.

Insomnia symptom scale: Self-evaluation of sleep disturbances was documented using the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS)[9], which was created in 2000 in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases (10th edition) standards. The evaluation time of the scale was 1 month. The higher the score, the worse the sleep quality, and a total score of 6 points or more indicates a high probability of insomnia (sensitivity 93%, specificity 85%)[10]. According to a previous study, the AIS may be used as a screening tool to accurately diagnose insomnia because of its high sensitivity and specificity[11].

Psychological feeling scale: The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7)[12] was used to assess the degree of generalized anxiety. The scale contains seven items, with a total range of 0–21. A score less than or equal to 4 indicates no anxiety symptoms, while 5, 10, and 15 correspond to mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively[13]. The Geriatric Depression Scale-15 (GDS-15)[14] was used to assess the degree of generalized depression. The scale has 15 entries, each with two answers: “yes” (1 score) or “no” (0 points). A score of 0–4 is considered no depression, 5–10 indicates mild depression, and 11–15 indicates major depression[15]. The Memorial University of Newfoundland Scale of Happiness (MUNSH) was used to measure subjective well-being. The scale contains 24 entries, of which five reflect positive emotions (PA), five reflect negative emotions (NA), seven reflect positive experiences (PE), and seven reflect negative experiences (NE). The total MUNSH score was calculated as follows: Total happiness = PA – NA + PE – NE + 24, ranging from 0 to 48[16].

Functional status scale: The Barthel index (BI)[17] is an ordinal scale used to measure a patient’s ability of daily living, including eating, bathing, and dressing, using a 10 point scale for each item. A perfect score is 100, ranging from 0 (totally dependent) to 100 (totally independent). A score of less than 100 indicates impaired activities of daily living[18]. The Morse Fall Scale (MFS)[19] was used to measure fall risk, including fall history, disease diagnosis, walking, intravenous fluid, gait, and cognitive status, with a maximum score of 125. A score < 25 indicates low fall risk, 25–45 indicates medium fall risk, and > 45 indicates high fall risk[20]. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)[21] includes five cognitive aspects: Orientation, memory, attention/computation, memory, and language, with a total score of 30. Scores of less than 24 (> 6 years of education or intermediate or above), 20 (< 6 years of education), and 17 (illiterate) were considered cognitively impaired[22].

Health-related quality of life scale: The Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36) has eight dimensions: Physical function (PF), role-physical (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role-emotional (RE), and MH, each of which is scored on a scale of 100, with scores proportional to quality of life[23].

Quality control was performed as follows: (1) Using uniform inclusion and exclusion criteria; (2) through face-to-face interviews, using a unified scale for self-reporting by patients; (3) data collection by regular personnel; (4) provision of relevant training to all survey members before the survey, such as insomnia-related knowledge, unified guidance, scale content and precautions; (5) surveys conducted in a small area in advance to observe the rationality and operability of the questionnaire; (6) before data entry, training and guidance was provided to entry personnel, and all data was processed according to the unified scoring standard; (7) before data analysis, coding and data entry were checked for errors; and (8) two-person entry verification was implemented during to ensure the reliability of the data.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 23.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD, using the independent-samples t-test. Continuous variables with a non-normal distribution were represented as median and quartile [M (Q25, Q75)], and non-parametric tests were used. Categorical variables were expressed in terms of frequency and composition ratio [n (%)], and the chi-squared test was used for statistical difference analysis. The correlation between insomnia and psychological status, daily living ability, and quality of life scores was analyzed using the double correlation variable and Spearman correlation coefficient when the data did not fit a normal distribution. Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the risk factors for insomnia. All statistical analyses were performed using two-sided tests, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Of the 100 elderly hospitalized patients, 19 were included in the insomnia group and the remaining 81 were included in the non-insomnia group. Cohabitation and marriage status were significantly different between the two groups (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences in age, sex, BMI, place of residence, monthly income, education level, profession, drinking, smoking, or physical activity (P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Items | Insomnia (n = 19) | Non- insomnia (n = 81) | P value |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 74.68 ± 7.95 | 71.12 ± 6.86 | 0.051 |

| Sex | 0.669 | ||

| Male | 10 (52.63) | 47 (58.02) | |

| Female | 9 (47.37) | 34 (41.98) | |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 24.22 (20.05, 26.42) | 22.32 (20.7, 25.44) | 0.524 |

| Place of residence | 0.999 | ||

| Town | 2 (10.53) | 7 (8.64) | |

| Other | 17 (89.47) | 74 (91.36) | |

| Cohabitation | 0.032 | ||

| Living with children | 9 (47.37) | 29 (35.80) | |

| Living with spouse | 6 (31.58) | 48 (59.26) | |

| Living alone | 4 (21.05) | 4 (4.94) | |

| Monthly income | 0.427 | ||

| ≥ 2000 | 12 (63.16) | 43 (53.09) | |

| 2000 | 7 (36.84) | 38 (46.91) | |

| Marital status | 0.041 | ||

| Married | 12 (63.16) | 70 (86.42) | |

| Divorced/widowed | 7 (36.84) | 11 (13.58) | |

| Education level | 0.999 | ||

| ≤ 9 yr | 15 (78.95) | 64 (79.01) | |

| 9 yr | 4 (21.05) | 17 (20.99) | |

| Profession | 0.495 | ||

| Public and business personnel | 7 (36.84) | 18 (22.22) | |

| Farmer | 6 (31.58) | 35 (43.21) | |

| Laborer | 5 (26.32) | 26 (32.10) | |

| Other | 1 (5.23) | 2 (2.47) | |

| Smoking | 0.234 | ||

| Yes | 0 | 10 (12.35) | |

| No | 19 (100) | 71 (87.65) | |

| Drinking | 0.185 | ||

| Yes | 2 (10.53) | 23 (28.40) | |

| No | 17 (89.47) | 58 (71.60) | |

| Physical exercise | 0.951 | ||

| Yes | 10 (52.63) | 42 (51.85) | |

| No | 9 (47.37) | 39 (48.15) |

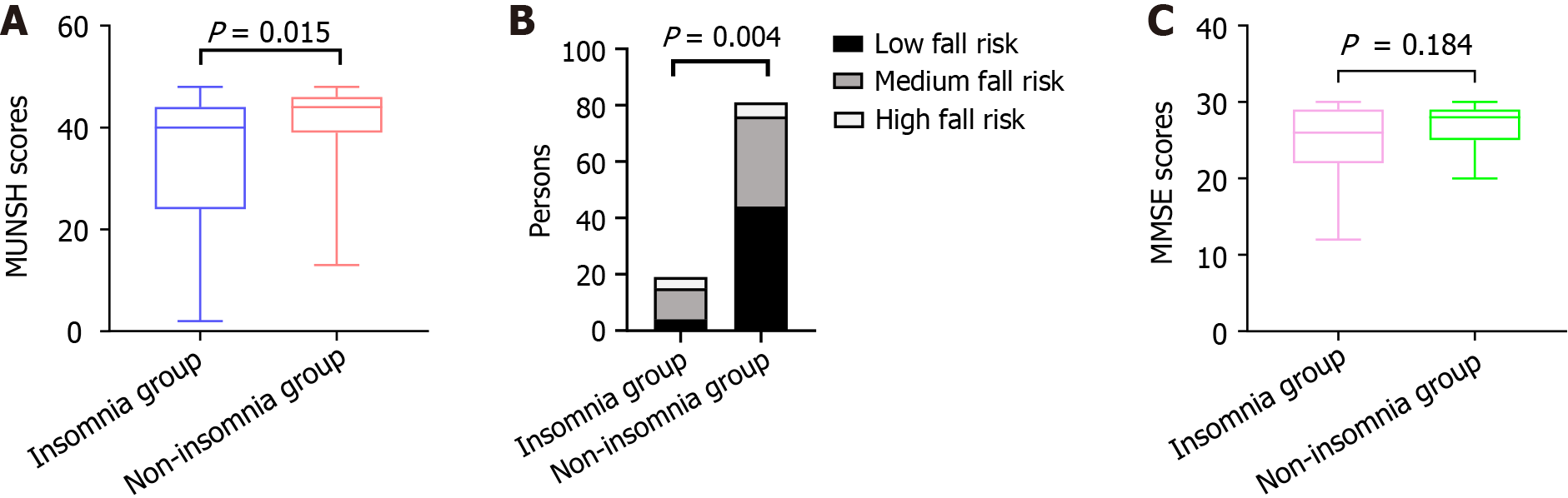

There were eight patients in the insomnia group and seven in the non-insomnia group with GDA-7 ≥ 5. The incidence of anxiety in the insomnia group was significantly higher than that in the non-insomnia group [42.11% (8/19) vs 8.64% (7/81), P < 0.05]. There were 11 and 8 cases in the insomnia and non-insomnia groups with GDS-15 ≥ 5, respectively. The incidence of depression in the insomnia group was significantly higher than that in the non-insomnia group [57.89% (11/19) vs 9.88% (8/81), P < 0.05]. The MUNSH scores in the insomnia group were significantly lower than those in the non-insomnia group (P < 0.05; Figure 1A).

There were 11 and 25 patients in the insomnia and non-insomnia groups, respectively, with BI < 100. The incidence of impaired activities of daily living in the insomnia group was significantly higher than that in the non-insomnia group [57.89% (11/19) vs 30.86% (25/81), P < 0.05]. In the insomnia group, four patients had a low fall risk, 11 had a medium fall risk, and four had a high fall risk. In the non-insomnia group, 44 patients had a low fall risk, 32 had a medium fall risk, and five had a high fall risk. The severity of fall risk was higher in the insomnia group than in the non-insomnia group (P < 0.05; Figure 1B). There were no significant differences in MMSE scores between groups (P > 0.05; Figure 1C).

There were no significant differences in BP, SF, RE, MH between the two groups (P > 0.05). There were significant differences in the PF, RP, GH, VT, and total scores between the two groups (P < 0.05; Table 2).

| Item | Insomnia group (n = 19) | Non-insomnia group (n = 81) | P value |

| PF [score, M (Q25,Q75)] | 45.00 (5.00, 70.00) | 70.00 (40.00, 87.50) | 0.016 |

| RP [score, M (Q25,Q75)] | 0 (0, 25.00) | 50.00 (0, 100.00) | 0.016 |

| BP [score, M (Q25, Q75)] | 62.00 (52.00, 100.00) | 100.00 (62.00, 100.00) | 0.122 |

| GH [score, M (Q25, Q75)] | 52.00 (25.00, 70.00) | 65.00 (50.00, 76.00) | 0.035 |

| VT [score, M (Q25, Q75)] | 50.00 (25.00, 85.00) | 70.00 (55.00, 85.00) | 0.041 |

| SF [score, M (Q25, Q75)] | 62.50 (25.00, 87.50) | 75.00 (50.00, 100.00) | 0.079 |

| RE [score, M (Q25, Q75)] | 100.00 (0, 100.00) | 100.00 (0, 100.00) | 0.381 |

| MH [score, M (Q25, Q75)] | 72.00 (60.00, 92.00) | 84.00 (70.00, 92.00) | 0.192 |

| SF-36 (score, mean ± SD) | 419.58 ± 207.95 | 541.99 ± 178.45 | 0.011 |

The AIS, GAD-7, GDS-15, BI, MFS, MMSE, and SF-36 scores in the insomnia group are shown in Table 3. AIA scores positively correlated with GAD-7, GDS-15, and MFS scores (P < 0.05; Table 4).

| Item | Scores |

| AIS [score, M (Q25, Q75)] | 10.00 (8.00, 12.00) |

| GAD-7 [score, M (Q25, Q75)] | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00) |

| GDS-15 (score, mean ± SD) | 5.16 ± 2.97 |

| MUNSH [score, M (Q25, Q75)] | 40.00 (24.00, 44.00) |

| BI [score, M (Q25, Q75)] | 95.00 (70.00, 100.00) |

| MFS [score, M (Q25, Q75)] | 35.00 (25.00, 45.00) |

| MMSE [score, M (Q25, Q75)] | 26.00 (22.00, 29.00) |

| SF-36 (score, mean ± SD) | 419.58 ± 207.95 |

| Item | AIS score | |

| r | P value | |

| GAD-7 score | 0.470 | 0.042 |

| GDS-15 score | 0.459 | 0.048 |

| MUNSH score | -0.185 | 0.448 |

| BI | -0.095 | 0.698 |

| MFS score | 0.743 | < 0.001 |

| MMSE score | -0.414 | 0.078 |

| SF-36 score | -0.324 | 0.176 |

Statistically significant indicators in the univariate analysis were taken as independent variables (Table 5) and insomnia as a dependent variable (0 = no, 1 = yes) in the logistic regression equation. Logistic regression analysis showed that GDS-15 ≥ 5 was an independent risk factor for insomnia in elderly hospitalized patients (Table 6).

| Item | Assignment |

| Cohabitation | 1: Living with children; 2: Living with spouse; 3: Living alone |

| Marital status | 1: Married; 2: Divorced/widowed |

| GAD-7 | 1: Score < 5; 2: Score ≥ 5 |

| GDS-15 | 1: Score < 5; 2: Score ≥ 5 |

| MUNSH | Original input |

| BI | 1: Score < 100; 2: Score of 100 |

| MFS | 1: Score < 25; 2: Score 25-45; 3: Score 45 |

| SF-36 | Original input |

| Item | B | SE | Wald | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Cohabitation | -0.252 | 0.480 | 0.275 | 0.600 | 0.777 (0.303-1.993) |

| Marital status | 0.911 | 0.775 | 1.381 | 0.240 | 2.487 (0.544-11.364) |

| GAD-7 | 1.437 | 0.944 | 2.319 | 0.128 | 4.209 (0.662-26.766) |

| GDS-15 | 1.821 | 0.737 | 6.103 | 0.013 | 6.177 (1.457-26.189) |

| MUNSH | -0.002 | 0.040 | 0.003 | 0.959 | 0.998 (0.923-1.079) |

| BI | -0.682 | 0.921 | 0.549 | 0.459 | 0.505 (0.083-3.075) |

| MFS | 0.342 | 0.657 | 0.272 | 0.602 | 1.408 (0.389-5.103) |

| SF-36 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.231 | 0.631 | 1.001 (0.995-1.008) |

The incidence of insomnia is increasing, with up to one in three adults worldwide suffering from this condition[24]. More than 300 million people in China had sleep disorders in 2021, and the adult insomnia rate is as high as 38.2%, according to the White Paper on China's National Healthy Sleep in 2022[25]. According to international studies, the incidence of insomnia symptoms among older adults ranges from 30%–48%[26]. The physiological activities of the body function decline with increasing age[27], and coupled with the impact of disease, the sleep quality of elderly patients is generally low, but their need for sleep is not reduced. Therefore, attention should be paid to the prevention and treatment of insomnia in elderly patients.

This study found that the incidence of insomnia symptoms among elderly hospitalized patients was 19%. Xiao et al[28] included 451 elderly patients in a geriatric unit and found that the incidence of insomnia was approximately 36.59% (165/451), which was higher than the results of this study and may be related to the different inclusion criteria. Their study included elderly patients aged > 65 years, including both outpatients and inpatients. In this study, elderly patients who lived alone, were divorced, or widowed had a high incidence of insomnia, which is consistent with the research results of Ma et al[29], which may be due to the higher level of stress brought about by living alone and marital change. Therefore, attention should be paid to screening for insomnia in the above population, strengthening their sleep care, and de

In this study, the incidence of anxiety and depression in elderly hospitalized patients with insomnia was significantly higher than that in those without insomnia symptoms, and patients with insomnia had significantly lower subjective well-being than those without insomnia. In addition, correlation analysis showed that insomnia was closely related to anxiety and depression, and logistic regression analysis showed that depression was a risk factor for insomnia in elderly hospitalized patients. While the mechanisms underlying insomnia, anxiety, and depression in older adults are still not fully understood, several studies have shown that insomnia in older adults can be accompanied by anxiety, depression, and other psychological conditions[30-32]. A cross-sectional study also showed that depression is a risk factor for insomnia in older adults[33]. Based on this data, it is recommended to combine the assessment and treatment of insomnia, anxiety, depression, and cognitive function in elderly hospitalized patients and focus on the psychological symptoms and cognitive function of elderly patients while performing sleep monitoring. Further identification of depression, anxiety, other NA, and cognitive function impairments is necessary, particularly for older patients who already have insomnia. At the same time, targeted interventions should be provided as early as possible, with a focus on MH education for older patients with insomnia to prevent or delay its further occurrence and development.

This study found that elderly inpatients with insomnia also have functional deficiencies in daily activities and a high risk of falling, and insomnia is positively correlated with falling risk. Takada et al[34] noted that the number of sleepless nights can predict the risk of falls in older adults, which may be related to sleep disturbances, unsteady gait, and poor balance. Our study did not establish a cause-and-effect relationship between insomnia and the risk of falling. Therefore, elderly inpatients should pay attention to their daily activities while reducing their symptoms of insomnia, be provided assistance as necessary, pay attention to patient safety, and avoid falling.

In terms of health-related quality of life, this study demonstrated that elderly inpatients with insomnia had worse physical quality of life, physiological function, physiological role, overall health, and VT. This is consistent with a report by Wang et al[35] in which patients with insomnia had a low quality of life. Therefore, we focused on the life care of elderly hospitalized patients with insomnia, starting with physiology and psychology, and effective insomnia treatment to improve their health-related quality of life.

However, this study has certain limitations. First, all information was gathered through patient self-reports. The AIS was created in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases (10th edition) standard, and the relevant scales were used in previous studies; however, the study did not adhere to the guidelines of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders[36] to assess insomnia and objective sleep measurement was not performed. Secondly, this was a cross-sectional study. We were unable to determine whether there was a connection between insomnia and psychosomatic disorders, and further prospective studies are required to confirm this causal link. Finally, this study considered the differences in sociodemographic factors, psychological feelings, functional status, and health-related quality of life of patients but did not consider the differences in the diseases of the patients.

The findings of this study demonstrate that insomnia significantly affects the psychological and functional states of elderly hospitalized patients, which eventually results in a reduction in their health-related quality of life. Therefore, more attention should be paid to the sleep conditions of elderly hospitalized patients, screening and identifying patients with insomnia early, taking multiple measures to relieve insomnia symptoms, and improving quality of life.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jucker M, Germany S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Van Someren EJW. Brain mechanisms of insomnia: new perspectives on causes and consequences. Physiol Rev. 2021;101:995-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kronholm E, Partonen T, Härmä M, Hublin C, Lallukka T, Peltonen M, Laatikainen T. Prevalence of insomnia-related symptoms continues to increase in the Finnish working-age population. J Sleep Res. 2016;25:454-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Boyle CC, Cho JH, Eisenberger NI, Olmstead RE, Piber D, Sadeghi N, Tazhibi M, Irwin MR. Motivation and sensitivity to monetary reward in late-life insomnia: moderating role of sex and the inflammatory marker CRP. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:1664-1671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Connor AE, Baumgartner RN, Pinkston CM, Boone SD, Baumgartner KB. Obesity, ethnicity, and quality of life among breast cancer survivors and women without breast cancer: the long-term quality of life follow-up study. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:115-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gnanasakthy A, Barrett A, Evans E, D'Alessio D, Romano CD. A Review of Patient-Reported Outcomes Labeling for Oncology Drugs Approved by the FDA and the EMA (2012-2016). Value Health. 2019;22:203-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen YT, Tan YZ, Cheen M, Wee HL. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Registry-Based Studies of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: a Systematic Review. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19:135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Javid SH, Lawrence SO, Lavallee DC. Prioritizing Patient-Reported Outcomes in Breast Cancer Surgery Quality Improvement. Breast J. 2017;23:127-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Smith BD, Lei X, Diao K, Xu Y, Shen Y, Smith GL, Giordano SH, DeSnyder SM, Hunt KK, Teshome M, Jagsi R, Shaitelman SF, Peterson SK, Swanick CW. Effect of Surgeon Factors on Long-Term Patient-Reported Outcomes After Breast-Conserving Therapy in Older Breast Cancer Survivors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:1013-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. Athens Insomnia Scale: validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:555-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 809] [Cited by in RCA: 1062] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. The diagnostic validity of the Athens Insomnia Scale. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:263-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Psarros C, Theleritis C, Economou M, Tzavara C, Kioulos KT, Mantonakis L, Soldatos CR, Bergiannaki JD. Insomnia and PTSD one month after wildfires: evidence for an independent role of the "fear of imminent death". Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2017;21:137-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11947] [Cited by in RCA: 18864] [Article Influence: 992.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tian J, Yu H, Austin L. The Effect of Physical Activity on Anxiety: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being and the Moderating Role of Gender. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2022;15:3167-3178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric depression scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165-173. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3109] [Cited by in RCA: 3176] [Article Influence: 186.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wen J, Wu Y, Peng L, Chen S, Yuan J, Wang W, Cong L. Constructing and Verifying an Alexithymia Risk-Prediction Model for Older Adults with Chronic Diseases Living in Nursing Homes: A Cross-Sectional Study in China. Geriatrics (Basel). 2022;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhang Q, Yang Y, Zhang GL. Influence of Life Meaning on Subjective Well-Being of Older People: Serial Multiple Mediation of Exercise Identification and Amount of Exercise. Front Public Health. 2021;9:515484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61-65. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Nicolai M, Casoni E, Bertino E, David L, Polverigiani C, Mallucci F, Fioretti P, Leonzi S, Bevilacqua R, Barbarossa F, Maranesi E, Baccini M, Barboni I, Riccardi GR. Evaluation of the Italian version of the elderly mobility scale in older hospitalized patients. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1274047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Morse JM, Black C, Oberle K, Donahue P. A prospective study to identify the fall-prone patient. Soc Sci Med. 1989;28:81-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sun C, Chen M, Wang X, Qi B, Yin H, Ji Y, Yuan N, Wang S, Zhu L, Wei X. Effect of Baduanjin exercise on primary osteoporosis: study protocol for randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2023;23:325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56757] [Cited by in RCA: 60713] [Article Influence: 1214.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wu F, Liu H, Liu W. Association between sensation, perception, negative socio-psychological factors and cognitive impairment. Heliyon. 2023;9:e22101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Barbos V, Feciche B, Bratosin F, Tummala D, Shetty USA, Latcu S, Croitor A, Dema V, Bardan R, Cumpanas AA. Pandemic Stressors and Adaptive Responses: A Longitudinal Analysis of the Quality of Life and Psychosocial Dynamics among Urothelial Cancer Patients. J Pers Med. 2023;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zheng JW, Meng SQ, Liu WY, Chang XW, Shi J. [Appropriate Use and Abuse of Sedative-Hypnotic Drugs]. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2023;54:231-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Liang M, Guo L, Huo J, Zhou G. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in Chinese adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0247333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Patel D, Steinberg J, Patel P. Insomnia in the Elderly: A Review. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14:1017-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Suzuki K, Miyamoto M, Hirata K. Sleep disorders in the elderly: Diagnosis and management. J Gen Fam Med. 2017;18:61-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Xiao X, Li L, Yang H, Peng L, Guo C, Cui W, Liu S, Yu R, Zhang X, Zhang M. Analysis of the incidence of falls and related factors in elderly patients based on comprehensive geriatric assessment. Aging Med (Milton). 2023;6:245-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ma Y, Hu Z, Qin X, Chen R, Zhou Y. Prevalence and socio-economic correlates of insomnia among older people in Anhui, China. Australas J Ageing. 2018;37:E91-E96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wang YM, Song M, Wang R, Shi L, He J, Fan TT, Chen WH, Wang L, Yu LL, Gao YY, Zhao XC, Li N, Han Y, Liu MY, Lu L, Wang XY. Insomnia and Multimorbidity in the Community Elderly in China. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:591-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Cross NE, Carrier J, Postuma RB, Gosselin N, Kakinami L, Thompson C, Chouchou F, Dang-Vu TT. Association between insomnia disorder and cognitive function in middle-aged and older adults: a cross-sectional analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Sleep. 2019;42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fu YY, Ji XW. Intergenerational relationships and depressive symptoms among older adults in urban China: The roles of loneliness and insomnia symptoms. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28:1310-1322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zou Y, Chen Y, Yu W, Chen T, Tian Q, Tu Q, Deng Y, Duan J, Xiao M, Lü Y. The prevalence and clinical risk factors of insomnia in the Chinese elderly based on comprehensive geriatric assessment in Chongqing population. Psychogeriatrics. 2019;19:384-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Takada S, Yamamoto Y, Shimizu S, Kimachi M, Ikenoue T, Fukuma S, Onishi Y, Takegami M, Yamazaki S, Ono R, Sekiguchi M, Otani K, Kikuchi SI, Konno SI, Fukuhara S. Association Between Subjective Sleep Quality and Future Risk of Falls in Older People: Results From LOHAS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73:1205-1211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wang YM, Chen HG, Song M, Xu SJ, Yu LL, Wang L, Wang R, Shi L, He J, Huang YQ, Sun HQ, Pan CY, Wang XY, Lu L. Prevalence of insomnia and its risk factors in older individuals: a community-based study in four cities of Hebei Province, China. Sleep Med. 2016;19:116-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Maness DL, Khan M. Nonpharmacologic Management of Chronic Insomnia. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92:1058-1064. [PubMed] |