Published online May 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i5.670

Revised: April 4, 2024

Accepted: April 10, 2024

Published online: May 19, 2024

Processing time: 86 Days and 23.9 Hours

Epilepsy is a nervous system disease characterized by recurrent attacks, a long disease course, and an unfavorable prognosis. It is associated with an enduring therapeutic process, and finding a cure has been difficult. Patients with epilepsy are predisposed to adverse moods, such as resistance, anxiety, nervousness, and anxiety, which compromise treatment compliance and overall efficacy.

To explored the influence of intensive psychological intervention on treatment compliance, psychological status, and quality of life (QOL) of patients with epilepsy.

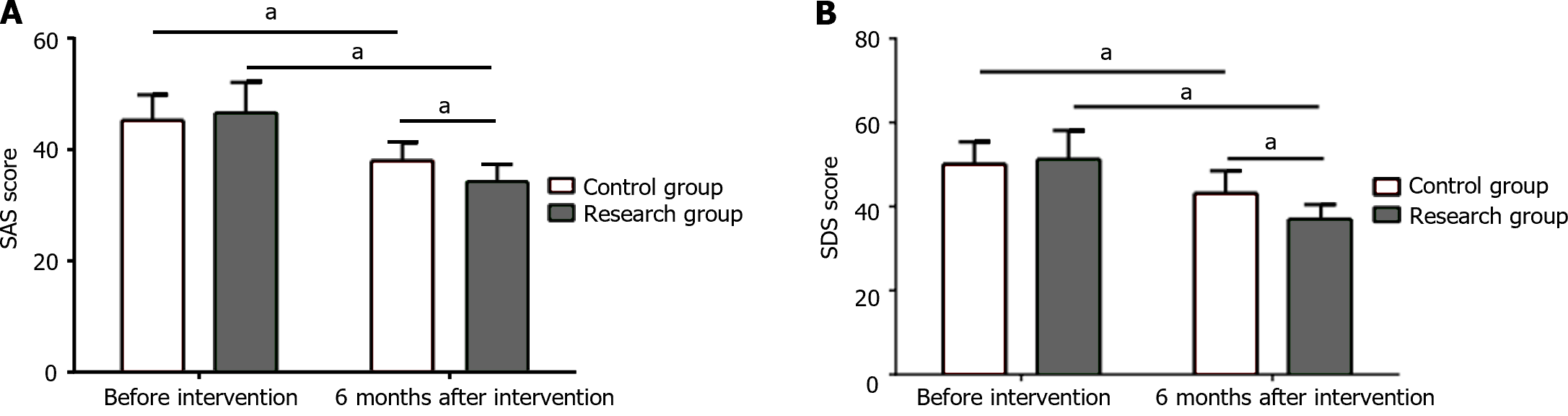

The clinical data of 105 patients with epilepsy admitted between December 2019 and July 2023 were retrospectively analyzed, including those of 50 patients who underwent routine intervention (control group) and 55 who underwent intensive psychological intervention (research group). Treatment compliance, psychological status based on the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Depression Scale Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores, hope level assessed using the Herth Hope Scale (HHS), psychological resilience evaluated using the Psychological Resilience Scale, and QOL determined using the QOL in Epilepsy-31 Inventory (QOLIE-31) were comparatively analyzed.

Treatment compliance in the research group was 85.5%, which is significantly better than the 68.0% of the control group. No notable intergroup differences in preinterventional SAS and SDS scores were identified (P > 0.05); however, after the intervention, the SAS and SDS scores decreased significantly in the two groups, especially in the research group (P < 0.05). The two groups also exhibited no significant differences in preinterventional HHS, Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), and QOLIE-31 scores (P > 0.05). After 6 months of intervention, the research group showed evidently higher HHS, CD-RISC, tenacity, optimism, strength, and QOLIE-31 scores (P < 0.05).

Intensive psychological intervention enhances treatment compliance, psychological status, and QOL of patients with epilepsy.

Core Tip: Epilepsy is a common chronic disease of the nervous system. Current treatment of epilepsy is mainly based on symptomatic treatment. Patients with poorly controlled seizures are at a higher risk of depression than those with well-controlled seizures. This study mainly explores the influence of intensive psychological intervention on the treatment compliance, psychological status, and quality of life of patients with epilepsy.

- Citation: Zhang SH, Wang JH, Liu HY, Zhang YX, Lin YL, Wu BY. Effects of intensive psychological intervention on treatment compliance, psychological status, and quality of life of patients with epilepsy. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(5): 670-677

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i5/670.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i5.670

Epilepsy is a common chronic disease of the nervous system that is characterized by a persistent predisposition for seizures, which is not caused by any direct central nervous system injury, but by the neurobiological, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of epileptic seizures[1-3]. The prevalence of epilepsy is approximately 0.5%-1%[4], with a slightly higher incidence in men than in women, especially in the youngest and oldest age groups[5,6]. Genetic susceptibility to seizures varies, as does the distribution of some environmental risk factors, which may explain the global heterogeneity of the incidence, course, and consequences of epilepsy[7]. In addition to the recurrence of seizures, the underlying etiology and adverse effects of treatment significantly affect the patient’s quality of life (QOL) and make the disease a complex health burden[8].

The treatment of epilepsy is currently based on symptomatic treatment[9]. Most patients can achieve seizure freedom through the first two appropriate drug trials. Those who fail to achieve a satisfactory response are defined as resistant and can eventually develop refractory epilepsy[10,11]. Psychiatric disorders are relatively rare but serious complications of epilepsy[12]. Current epidemiological research has shown a 5.6% incidence of psychiatric disorders in an unselected sample of patients with epilepsy[13]. In addition, patients with poorly controlled seizures are at a higher risk of depression than those with well-controlled seizures[14]. However, anxiety is not currently of sufficient interest in patients with epilepsy, even though it is more prevalent than depression[15]. Because of the long course of epilepsy and the unpredictability of seizures, patients are prone to nervous, anxious, and other negative emotions, leading to decreased treatment compliance, which is not conducive to the outcome of the disease. In the lengthy process of antiepileptic treatment, recurrent episodes and the huge psychological pressure caused by economic burden and social discrimination will seriously affect the normal work and life of patients[16]. Furthermore, the level of self-identification of patients with epilepsy also diminishes, leading to behavioral abnormalities, such as inner pain[17]. Therefore, psychological intervention for patients with epilepsy is a crucial feature of clinical treatment. This study retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of patients with epilepsy to explore the impact of intensive psychological intervention on treatment compliance, psychological status, and QOL of these patients.

This retrospective analysis included 105 patients with epilepsy admitted between December 2019 and July 2023. The inclusion criteria were the following: (1) Meeting the epilepsy diagnosis criteria of the International League Against Epilepsy in 2017; (2) aged 18-60 years; (3) course of epilepsy ≥ 6 months; (4) use of antiepileptic drugs ≥ 3 months; (5) no communication or hearing impairment; (6) normal comprehension and communication skills and certain reading comprehension ability; and (7) complete clinical and follow-up data. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Psychogenic pseudoepileptic seizures; (2) history of epilepsy-related surgery; (3) severe mental and neurological complications; (4) diagnosis of malignant tumor(s); (5) refusal to undergo neuropsychological evaluation; and (6) incomplete clinical data.

Patients were divided into either the control or research group based on different intervention methods documented in their records, with 50 cases in the control group and 55 cases in the research group. Patients in the control group underwent routine intervention based on the clinical treatment of the disease, i.e., safe nursing for the onset of the disease and adverse reactions, and oral explanation of disease-related knowledge. The main measures were as follows: (1) A protective belt, mouth opener, and other items were used to prevent bed falling and tongue biting, and local pressure was avoided as much as possible; and (2) valproic acid was administered to patients with generalized seizures, and antiviral therapy was strengthened for those with viral encephalitis. During seizures, phenobarbital sodium was injected intramuscularly or diazepam intravenously.

In addition to the above measures, those in the research group underwent intensive psychological intervention: (1) The patients and their families were assisted in establishing a correct understanding of the disease and reducing their psychological burden by providing health education manuals, watching videos, listening to audio presentations, holding seminars, etc.; (2) the patients were encouraged to participate in social activities more actively to help them realize their social values and improve their self-esteem; (3) doctor-patient communication was enhanced, and effective communi

Determination of treatment compliance. Complete compliance: The patient can completely follow the doctor’s advice to accomplish various interventions and take the medication on time at the dosage prescribed during the treatment process. Partial compliance: The patient can partially accomplish various interventions and follow the instructions on medication time and dosage according to the doctor’s advice. Noncompliance: The patient can occasionally follow the doctor’s advice for treatment or cooperate with treatment when the condition worsens but does not understand the side effects of drugs. Compliance = complete compliance + partial compliance.

Psychological state assessment. Patients’ negative emotions before and 6 months after intervention were evaluated using Zung’s Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Scale Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), with the score in positive association with the severity of anxiety and depression.

Hope level evaluation. The hope level of patients before and 6 months after intervention was assessed using the Herth Hope Scale (HHS). The scale contains three dimensions, namely, temporality and future orientation (T), positive readiness and expectancy (P), and interconnectedness (I). Each dimension has four items that can be classified into four grades, with the possible total score ranging from 12 to 48. A higher score corresponds to a higher hope level, with 12-23, 23-35, and 35-48 points indicating low, medium, and high levels of hope, respectively.

Psychological resilience evaluation: We used the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) to assess patients’ psychological resilience before and 6 months after intervention. The scale consists of 25 items that fall into three dimensions: tenacity, strength, and optimism. The scale uses a five-point scoring method, with 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 corresponding to never, rarely, sometimes, often, and always, respectively. The total score (range: 0-100) = tenacity score + strength score + optimism score. A higher score indicates better psychological resilience.

QOL of patients with epilepsy. QOL was assessed before and 6 months after the intervention using the QOL in Epilepsy-31 Inventory (QOLIE-31). QOLIE-31 exhibited good reliability and validity in Chinese adult patients with epilepsy. The scale consists of seven components: Seizure worry, overall QOL, emotional well-being, energy/fatigue, cognitive functioning, medication effects, and social functioning, each scored on a percentage scale. Scoring system: The score of each item is converted to its corresponding points (0-100), and the total score of each dimension is obtained by dividing the sum of the conversion points of the items in each dimension by the total number of items. The higher the score, the better the QOL. Finally, the total score of the seven dimensions is multiplied by the weight and then added to obtain the total QOL score.

Data analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0, and statistical significance was set at P-value < 0.05. Measurement data are expressed as mean ± SD. Student’s t-test was used for intergroup comparisons of means and paired t-tests for intragroup comparisons before and after intervention. The rank-sum test was used to compare the ranked data. Count data are expressed as percentages, for which the chi-square test was used for comparison.

Comparison of general data revealed no statistical intergroup differences in age, sex, course of disease, monthly frequency of attacks, and number of epileptic seizure types (P > 0.05), indicating that the two groups of patients were comparable (Table 1).

| Control group (n = 50) | Research group (n = 55) | χ2/t | P value | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 24 (48.0) | 29 (52.7) | 0.234 | 0.629 |

| Female | 26 (52.0) | 26 (47.3) | 0.725 | 0.470 |

| Age (yr) | 36.65 ± 6.48 | 37.29 ± 6.97 | ||

| Disease course (months) | 18.24 ± 4.38 | 18.39 ± 4.33 | 0.451 | 0.653 |

| Monthly frequency of seizure attacks (times) | 6.15 ± 3.85 | 6.27 ± 3.91 | 0.469 | 0.640 |

| Seizure type | 0.856 | 0.652 | ||

| Simple focal seizures | 5 (10.0) | 3 (5.5) | ||

| Absence seizures | 16 (32.0) | 20 (36.3) | ||

| Grand mal seizures | 29 (58.0) | 32 (58.2) |

The research group (85.5%) exhibited significantly higher treatment compliance than the control group (68.0%) (Table 2).

| Control group (n = 50) | Research group (n = 55) | χ2 | P value | |

| Complete compliance | 20 (40.0) | 31 (56.4) | 4.525 | 0.033 |

| Partial compliance | 14 (28.0) | 16 (29.1) | ||

| Non-compliance | 16 (32.0) | 8 (14.5) | ||

| Compliance | 34 (68.0) | 47 (85.5) |

The two groups showed similar SAS and SDS scores before intervention (P > 0.05); a marked reduction was observed in SAS and SDS scores in both groups after intervention, with even lower scores in the research group (P < 0.05; Figure 1).

The preinterventional T, P, and I scores and overall hope level were similar between the research and control groups (P > 0.05). After the intervention, the T, P, and I scores of both groups and the overall hope level increased statistically, especially in the research group (P < 0.05; Table 3).

| Control group (n = 50) | Research group (n = 55) | t | P value | ||

| Temporarily and future orientation (T) | Before intervention | 7.86 ± 0.93 | 7.82 ± 1.12 | 0.198 | 0.843 |

| 6 months after intervention | 9.90 ± 1.39a | 11.07 ± 1.51a | 4.118 | < 0.0001 | |

| Positive readiness and expectancy (P) | Before intervention | 8.26 ± 1.31 | 8.49 ± 1.17 | 0.950 | 0.344 |

| 6 months after intervention | 10.50 ± 1.82a | 12.80 ± 1.43a | 7.234 | < 0.0001 | |

| Interconnectedness (I) | Before intervention | 8.56 ± 1.75 | 9.13 ± 1.52 | 1.786 | 0.077 |

| 6 months after intervention | 11.54 ± 2.16a | 13.58 ± 1.80a | 5.274 | < 0.0001 | |

| Overall hope level | Before intervention | 24.68 ± 2.30 | 25.44 ± 2.42 | 1.646 | 0.103 |

| 6 months after intervention | 31.94 ± 2.80a | 37.48 ± 3.25a | 9.313 | < 0.0001 |

The two groups did not differ significantly in the preinterventional total and individual dimension scores for CD-RISC (P > 0.05). Both groups showed significant increases in the total score and scores for tenacity, optimism, and strength at 6 months after intervention, with even higher scores in the research group (P < 0.05; Table 4).

| Control group (n = 50) | Research group (n = 55) | t | P value | ||

| Tenacity | Before intervention | 24.14 ± 4.07 | 24.53 ± 3.71 | 0.514 | 0.609 |

| 6 months after intervention | 33.10 ± 5.41a | 36.13 ± 5.26a | 2.908 | 0.044 | |

| Optimism | Before intervention | 9.46 ± 2.58 | 9.75 ± 2.41 | 0.595 | 0.553 |

| 6 months after intervention | 19.02 ± 3.31a | 22.15 ± 2.79a | 5.255 | < 0.0001 | |

| Strength | Before intervention | 7.94 ± 2.41 | 8.60 ± 2.09 | 1.503 | 0.136 |

| 6 months after intervention | 11.00 ± 1.58a | 13.60 ± 1.31a | 9.210 | < 0.0001 | |

| Total score | Before intervention | 41.54 ± 5.93 | 42.87 ± 4.33 | 1.321 | 0.189 |

| 6 months after intervention | 63.12 ± 6.60a | 71.87 ± 6.11a | 7.054 | < 0.0001 |

No notable intergroup differences were observed in the preinterventional total and individual dimension scores for QOLIE-31 (P > 0.05). After 6 months of intervention, the total and individual dimension scores for QOLIE-31 in both groups increase significantly, with higher scores in the research group than in the control group (P < 0.05; Table 5).

| Control group (n = 50) | Research group (n = 55) | t | P value | ||

| Seizure worry | Before intervention | 42.78 ± 6.21 | 43.15 ± 8.12 | 0.260 | 0.795 |

| 6 months after intervention | 53.10 ± 9.34a | 61.82 ± 7.20a | 5.385 | < 0.0001 | |

| Overall quality of life | Before intervention | 44.24 ± 6.32 | 45.78 ± 4.70 | 1.425 | 0.157 |

| 6 months after intervention | 55.66 ± 8.30a | 63.45 ± 7.19a | 5.152 | < 0.0001 | |

| Emotional well-being | Before intervention | 48.58 ± 5.41 | 47.64 ± 6.20 | 0.825 | 0.411 |

| 6 months after intervention | 58.34 ± 9.94a | 69.20 ± 8.62a | 5.995 | < 0.0001 | |

| Energy/fatigue | Before intervention | 50.46 ± 6.28 | 48.16 ± 7.86 | 1.646 | 0.103 |

| 6 months after intervention | 58.04 ± 7.13a | 69.71 ± 8.36a | 7.658 | < 0.0001 | |

| Cognitive functioning | Before intervention | 49.80 ± 3.94 | 51.02 ± 5.04 | 1.372 | 0.173 |

| 6 months after intervention | 59.72 ± 6.55a | 70.69 ± 6.56a | 7.021 | < 0.0001 | |

| Medication effects | Before intervention | 40.14 ± 7.72 | 42.22 ± 6.49 | 1.499 | 0.137 |

| 6 months after intervention | 57.50 ± 6.84a | 66.18 ± 5.71a | 7.081 | < 0.0001 | |

| Social functioning | Before intervention | 54.12 ± 6.38 | 53.82 ± 6.20 | 0.244 | 0.808 |

| 6 months after intervention | 63.88 ± 5.63a | 71.05 ± 6.56a | 5.981 | < 0.0001 | |

| Total score | Before intervention | 48.97 ± 2.33 | 49.13 ± 6.04 | 0.176 | 0.861 |

| 6 months after intervention | 59.13 ± 3.54a | 68.32 ± 3.34a | 14.578 | < 0.0001 |

Epilepsy is a chronic nervous system disease strongly associated with genetic factors, surgery, febrile convulsions, and brain trauma[18]. Given the current lack of specific therapeutic agents, the disease is treated based on the principles of improving patient QOL and controlling disease onset. Patients with epilepsy are often affected by intermittent seizure episodes, which restrict their life and work and severely affect their psychological state, resulting in a severely reduced QOL. Therefore, psychological intervention has important implications for the prognosis of patients with epilepsy.

This study mainly investigated the influence of intensive psychological intervention on the compliance, psychological state, and QOL of patients with epilepsy. The results showed a significant decrease in SAS and SDS scores and an increase in HHS, CD-RISC, tenacity, optimism, strength, and QOLIE-31 scores in patients with epilepsy who underwent intensive psychological intervention. Therefore, intensive psychological intervention promotes the improvement of the mental state and QOL of patients with epilepsy. Recurrent seizures may affect the function of the limbic system without directly influencing the development of depression and increase patients’ susceptibility to mental disorders and social stress[19]. A bidirectional relationship has also been established between epilepsy and depression[20]. In routine nursing, patients’ psychological problems can easily be overlooked. In contrast, intensive psychological intervention is a more detailed and optimized intervention mode that further strengthens the patient’s psychological state[21]. It extends and expands the advantages of the original intervention model, extends the research on the relevant factors affecting the mental state, and implements the corresponding measures. Strengthening health education during intensive psychological nursing can help patients correctly understand the disease and reduce their psychological burden. Furthermore, intensive psychological intervention monitors the patient’s psychological adjustment and enables the development of intervention strategies that can fully meet the needs of patients, minimize external causes of psychological stress, and enhance their psychological coping ability. Cognition, as the intermediary of emotional and behavioral responses, has a fundamental influence on the occurrence and changes in emotions and behaviors[22]. Intensive psychological intervention helps patients establish correct awareness about epilepsy through scientific and rational dialogues, relieves psychological conflicts, guides patients in expressing their depression, and helps regulate their emotions, thereby improving their views and attitudes and mitigating their irrational beliefs.

Furthermore, this study found that the treatment compliance of patients with epilepsy under intensive psychological intervention was 85.5%, which was significantly better than the 68.0% compliance rate of the routine intervention group. Depression and anxiety influence treatment compliance[23]. Depression and anxiety can affect patients’ adherence to treatment for several reasons. First, the expectation of treatment response is an essential component of patients’ treatment compliance, whereas recurrent seizures can affect patients’ motivation and confidence in treatment efficacy. Anxiety itself has various presentations, such as panic attacks, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder[24], among which generalized anxiety disorder has the greatest influence on treatment compliance[25]. Moreover, the postinterventional T, P, I, and QOL scores in the research group were higher than those in the control group, indicating high acceptance of the intensive psychological intervention model among patients with epilepsy, which, consequently, improved their hope level, changed their coping styles, and increased their QOL. People with epilepsy generally have a lower QOL, especially in terms of seizure worry and medication effects. Patients generally have a strong fear of disease recurrence, which may be related to the pain caused by the seizure itself or to the fear of shame related to others witnessing such episodes, resulting in reduced compliance with medication. Intensive psychological intervention can strengthen patients’ memories of successful cases, happiness, and warmth; increase their feelings of support from society and their families and reduce their seizure worry. In addition, “happy factor” feedback intervention can enhance patients’ sense of social identity and participation and promote in them a positive attitude in receiving disease treatment, which can obviously improve their QOL.

Because of its design, this study has some limitations. The retrospective design did not allow for the randomization of the two groups of patients, which would have compromised the similarity of patients within the groups. In addition, retrospective secondary data analysis carries the risk of information bias, especially with incomplete records encountered in such studies. The sample size may also be too small to reveal differences between the two groups. Therefore, the similarity of clinical outcomes between the two groups in our investigation may be a type II error. Furthermore, the study period was too short. A well-designed, randomized, controlled trial with prospective data collection and sample size calculations is needed to confirm our findings and evaluate the relationship between long-term clinical outcomes.

In conclusion, intensive psychological intervention for patients with epilepsy can help manage positive and negative effects, enhance treatment compliance, enable patients to actively cope with disease-related problems, and increase QOL. However, given the shortcomings of this study, further studies involving more cases and a longer research period are needed.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C, Grade C

Novelty: Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Dionisie V, Romania; Filip GA, Belgium S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YX

| 1. | Thijs RD, Surges R, O'Brien TJ, Sander JW. Epilepsy in adults. Lancet. 2019;393:689-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 662] [Cited by in RCA: 1237] [Article Influence: 206.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Beghi E. The Epidemiology of Epilepsy. Neuroepidemiology. 2020;54:185-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 680] [Article Influence: 113.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fisher RS, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, Elger C, Genton P, Lee P, Engel J Jr. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia. 2005;46:470-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2069] [Cited by in RCA: 2057] [Article Influence: 102.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fattorusso A, Matricardi S, Mencaroni E, Dell'Isola GB, Di Cara G, Striano P, Verrotti A. The Pharmacoresistant Epilepsy: An Overview on Existant and New Emerging Therapies. Front Neurol. 2021;12:674483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fiest KM, Sauro KM, Wiebe S, Patten SB, Kwon CS, Dykeman J, Pringsheim T, Lorenzetti DL, Jetté N. Prevalence and incidence of epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of international studies. Neurology. 2017;88:296-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 710] [Cited by in RCA: 1202] [Article Influence: 133.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sen A, Jette N, Husain M, Sander JW. Epilepsy in older people. Lancet. 2020;395:735-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kjeldsen MJ, Kyvik KO, Christensen K, Friis ML. Genetic and environmental factors in epilepsy: a population-based study of 11900 Danish twin pairs. Epilepsy Res. 2001;44:167-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Trinka E, Kwan P, Lee B, Dash A. Epilepsy in Asia: Disease burden, management barriers, and challenges. Epilepsia. 2019;60 Suppl 1:7-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shih JJ, Whitlock JB, Chimato N, Vargas E, Karceski SC, Frank RD. Epilepsy treatment in adults and adolescents: Expert opinion, 2016. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;69:186-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xu C, Gong Y, Wang Y, Chen Z. New advances in pharmacoresistant epilepsy towards precise management-from prognosis to treatments. Pharmacol Ther. 2022;233:108026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Janmohamed M, Brodie MJ, Kwan P. Pharmacoresistance - Epidemiology, mechanisms, and impact on epilepsy treatment. Neuropharmacology. 2020;168:107790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Maguire M, Singh J, Marson A. Epilepsy and psychosis: a practical approach. Pract Neurol. 2018;18:106-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Agrawal N, Mula M. Treatment of psychoses in patients with epilepsy: an update. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2019;9:2045125319862968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mula M. Depression in epilepsy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30:180-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hingray C, McGonigal A, Kotwas I, Micoulaud-Franchi JA. The Relationship Between Epilepsy and Anxiety Disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moon HJ, Seo JG, Park SP. Perceived stress and its predictors in people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;62:47-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rhodes PJ, Small NA, Ismail H, Wright JP. 'What really annoys me is people take it like it's a disability', epilepsy, disability and identity among people of Pakistani origin living in the UK. Ethn Health. 2008;13:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yang C, Shi Y, Li X, Guan L, Li H, Lin J. Cadherins and the pathogenesis of epilepsy. Cell Biochem Funct. 2022;40:336-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schmitz B. Depression and mania in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2005;46 Suppl 4:45-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Munger Clary HM. Depression and Epilepsy: The Bidirectional Relation Goes On and On…. Epilepsy Curr. 2023;23:222-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM, Glaser R, Emery CF, Crespin TR, Shapiro CL, Carson WE 3rd. Psychological, behavioral, and immune changes after a psychological intervention: a clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3570-3580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pessoa L. Emergent processes in cognitive-emotional interactions. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010;12:433-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2682] [Cited by in RCA: 2745] [Article Influence: 109.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Otto MW, Smits JA, Reese HE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65 Suppl 5:34-41. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Santana L, Fontenelle LF. A review of studies concerning treatment adherence of patients with anxiety disorders. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:427-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |