INTRODUCTION

Suicide is defined as a self-directed, harmful, intentional act that results in death[1]. Regardless of age, sex, occupation, or geographical location, individuals are vulnerable to suicide. As a dangerous behavior performed under the influence of multiple factors, suicide poses a significant threat to individuals’ physical and mental well-being, life safety, social welfare, and even regional development. Every suicide case is tragic, and suicide has become an urgent global public health issue[2-6]. The World Health Organization’s “Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative” report states that one person dies by suicide every 40 s worldwide, resulting in more than 800000 deaths each year[7]. Suicide has become one of the leading causes of death worldwide, with more than 1 in 100 deaths attributed to suicide, exceeding the number of deaths from malaria, HIV/AIDS, breast cancer, war, and homicide[8]. For example, in the United States, the suicide rate has been increasing continuously for two decades (since 2000). Between 2000 and 2018, the suicide rate in the United States increased by 35%. Although there was a slight decrease in the suicide rate in 2019 due to a slight decline among white individuals, the rates among all other racial/ethnic groups continued to increase or remain stable. The highest suicide rates were observed in the western, midwestern, and southern regions, and the suicide death rate was highest among individuals of specific racial/ethnic groups, such as non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native individuals. The first and second peaks in suicide mortality typically occur among young and older adults[9]. Moreover, the global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has further exacerbated the global risk of suicide. The pandemic has been associated with negative emotions such as distress, anxiety, fear of infection, depression, and insomnia among the general population[10], leading to an increased risk of mental disorders, chronic trauma, and stress, ultimately increasing suicidality and suicidal behaviors[11]. A retrospective study analyzing 24350 cases of suicide deaths in Nepal showed an overall increase in the monthly suicide rate, with an additional 0.28 suicides per 100000 people during the pandemic. Both male and female suicide rates have significantly increased, with rates of 0.26 and 0.3, respectively[12]. A study conducted among college students in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that 6999 participants reported engaging in non-suicidal self-injury, 3819 reported suicidal ideation, 1531 reported making a suicide plan, and 334 reported a suicide attempt in the past 12 months[13].

Although suicide can impact individuals in all age groups, suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) of adolescents deserve special attention. First, among the various groups at risk of suicide, young people are considered one of the most vulnerable[7], and suicide has become the fourth leading cause of death among the global population aged 15-29 years[14]. In the United States, for every 7 youth, there is 1 who has seriously considered suicide or made a suicide plan, and 1 out of 13 youths had attempted suicide in the previous year[15]. A study on suicidal ideation and behavior among high school students yielded similar conclusions. One study indicated that in 2019, approximately one-fifth of youths had seriously considered attempting suicide, one-sixth had made a suicide plan, one-eleventh had attempted suicide, and one-fortieth had made a suicide attempt requiring medical treatment[16]. Suicide, as a leading cause of death among adolescents, has become a critical global public health priority. Second, the prevention and control of adolescent suicide are crucial for addressing the issue of suicide. Many individuals who have previously considered or attempted suicide did so during their youth; suicide, as a risk event for which intervention can be provided at an early stage, provides a key opportunity for prevention during adolescence[17]. Research has shown that the number of people exhibiting suicidal behaviors dramatically increases during adolescence, with approximately one-third of adolescents with suicidal ideation developing a suicide plan, approximately 60% of adolescents with a suicide plan attempting suicide, and the majority of suicide attempts occurring within the first year after the onset of suicidal ideation[18]. Therefore, if we can fully understand the risk factors for adolescent suicide, promptly assess adolescents’ current psychological states, and provide timely warnings and proactive responses when risk factors or negative psychological states arise, we can achieve the goal of suicide prevention. Early intervention during the suicide trajectory can reduce the risk of death and save additional lives. Finally, adolescence is an important turning point in an individual’s life[19] and represents a critical period for individual physical and mental development as well as for exploring life experiences, seeking independence, and establishing intimate relationships[20,21]. The rapid development of the mind and body and rapid changes in life not only bring significant opportunities for growth and development for adolescents but also come with certain risks to their mental health[22-26] and lead to conflicts in life[27-31], which cannot be ignored in terms of the risk of suicide. In the future, the physical and mental health of adolescents requires broader public attention, more comprehensive care, and stronger support from society.

Therefore, adolescent suicide, as a public health issue with detrimental effects and causing significant harm, requires a more powerful and efficient global response. Social and emotional learning (SEL) is considered a powerful measure for addressing the crisis of adolescent suicide and resolving this issue[32]. As an integral part of education and human development, SEL is a process of cultivating social and emotional competencies in which young people acquire and apply knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop a healthy identity; manage emotions; achieve personal and collective goals; empathize with others; establish and maintain supportive relationships; and make responsible and compassionate decisions[33,34]. The important role of SEL in intervening in adolescent suicide has also been recognized in the World Health Organization’s “LIVE LIFE” suicide prevention guidelines, which identify “foster social-emotional life skills in adolescents” as a key effective intervention measure for suicide prevention[35]. Given the severity of the issue of adolescent suicide, the uniqueness of the adolescent population, and the importance of safeguarding adolescents’ well-being, it is necessary to systematically examine the risk factors for adolescent suicide and explore more effective solutions. Based on a review and analysis of the risk factors influencing adolescent suicide, this study examined the important role of SEL in the prevention and control of adolescent suicide and explored school-based preventive practices with an emphasis on social and emotional skills as interventions for adolescent suicide. Hopefully, this study will make a substantial contribution to safeguarding the well-being of adolescents and overcoming the crisis of adolescent suicide.

RISK FACTORS FOR ADOLESCENT SUICIDE

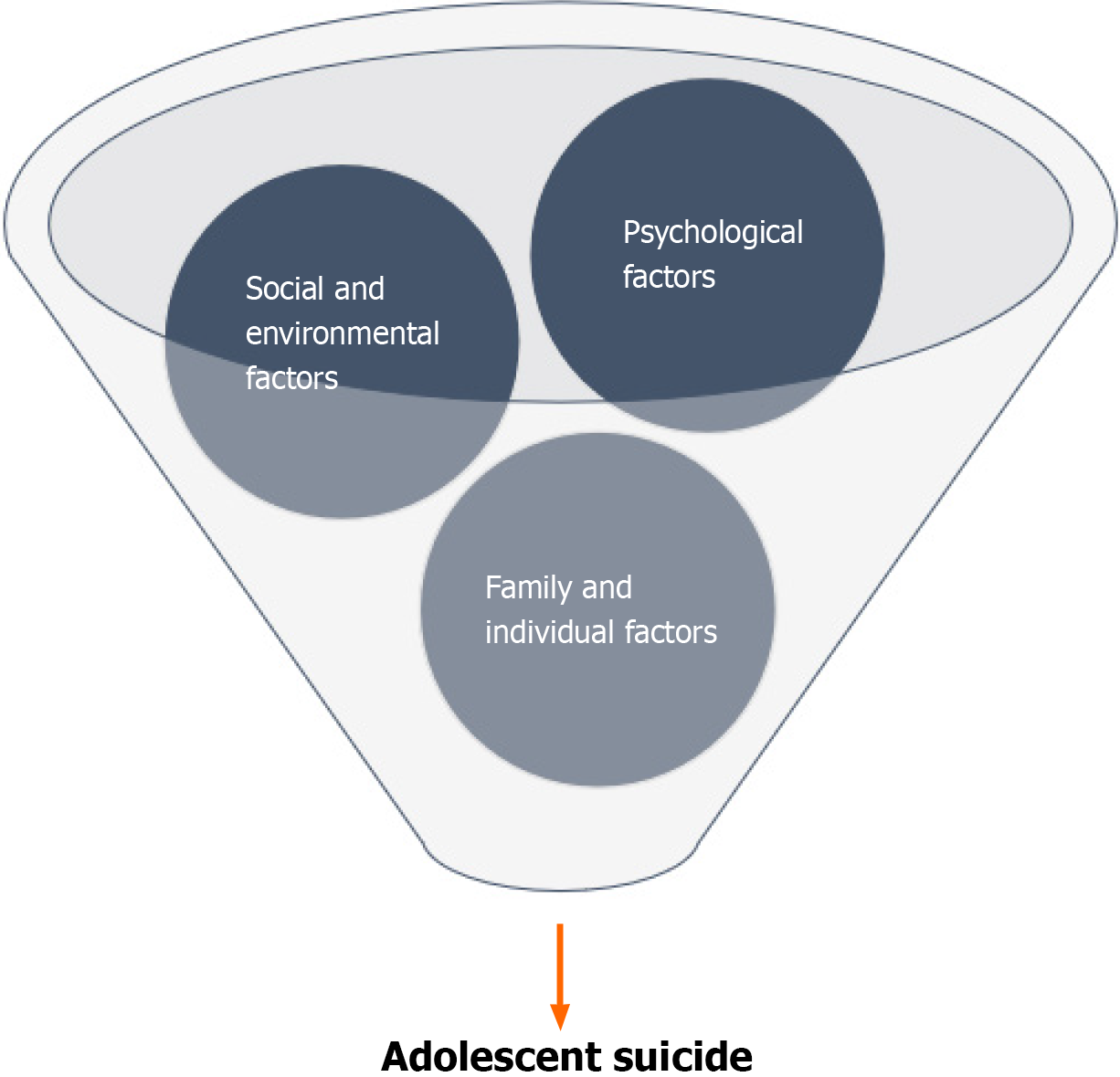

Psychological, social, family, individual, and environmental factors are important risk factors for adolescent suicide-related behaviors within the adolescent population (see Figure 1). These factors may contribute to the presence of suicidal vulnerability in adolescents through various direct, indirect, or combined pathways.

Figure 1

Various risk factors for adolescent suicide.

Psychological factors

The period from adolescence to early adulthood, ranging from late teens to twenties, is a period of profound change and significance[36]. Individuals at this stage of life experience the joy of growth and maturity, eagerly embracing their new life and gradually embarking on a new phase of their lives with numerous attempts. However, along with the accelerated pace of growth, adolescents also face significant psychological changes, identity and role transitions, and increasingly diverse and complex challenges from their families and institutions[37]. These changes and challenges often accompany immense psychological stress or even distress, which can lead to mental problems, including despair, anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and eating disorders; these mental problems are often linked to the risk of suicide-related behaviors and are considered important risk factors by scholars[38-40]. Research has indicated that individuals with psychiatric diseases account for the vast majority of suicide completers and attempters, whose prevalence is at least 10 times greater than that in the general population[41]. Individuals with bipolar disorder, characterized by alternating or mixed manic and depressive episodes, have the highest suicide rate among individuals with all other mental disorders, and suicide is approximately 20 to 30 times more common in the bipolar population than in the general population[42]. In 2019, of the 14 million individuals with eating disorders, nearly 3 million were children and adolescents; anorexia nervosa usually develops during adolescence or early adulthood, and bulimia nervosa is associated with a greater risk of suicide[43]. Although they are experiencing rapid changes in both their physical and mental states, adolescents are still limited by their developmental and age characteristics. Compared to adults, adolescents possess a certain level of immaturity and vulnerability, making them more susceptible to negative emotions or psychological problems in the face of setbacks or adverse events in life. If these issues are not promptly and properly addressed, adolescents may develop suicidal thoughts or even choose to prematurely end their lives under the influence of psychological factors.

Social factors

Race, socioeconomic status, stigma, and bullying are important social risk factors that contribute to adolescent suicide-related behaviors. There are significant racial differences in adolescents’ suicidal ideation-related behaviors. On the one hand, adolescents of multiple races are at high risk for suicide-related behaviors[44], with youth from ethnic minority backgrounds having the highest suicide risk during the early stages of life. Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian adolescents have the highest suicide risk during adolescence and young adulthood[45]. On the other hand, youth from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds also face barriers in accessing mental health services and encounter issues such as inadequate treatment[46,47]. Many adolescents at risk of suicide often lack or are unable to access necessary mental health interventions and services in a timely manner. Economic factors also influence suicide-related behaviors, with economic recessions appearing to increase overall suicide rates[48]. Economic downturns significantly affect the health, well-being, and living conditions of the population, and economic pressure and unemployment have devastating impacts on families, particularly children[49]. Globally, more than 75% of completed suicides occur in low- and middle-income countries[50], and 88% of adolescent suicide deaths are reported in low- and middle-income countries[8]. Children and adolescents from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds often face multiple life pressures; compared to those from higher socioeconomic backgrounds, children and adolescents from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to experience mental health problems[51]. After developing psychological issues, these children and adolescents are also more likely to be deterred from seeking treatment due to the high cost and heavy financial burden of these treatments, thus leading to a greater risk of suicide. Stigma is a social process aimed at excluding individuals who are considered potential sources of illness and may pose a threat to effective social life; individuals who are stigmatized experience passive negative emotional reactions from dominant others[52]. Stigmatization has undeniable direct and indirect harmful effects on children and adolescents[53]. The discrimination and shame brought about by stigma can result in worsened mental health conditions or increased mental illness burden among adolescents[54], leading to the emergence of suicidal ideation or suicidal behaviors. Furthermore, due to the fear of stigma-related risks, there may be delays in seeking treatment or poorer medication adherence, consequently resulting in an increase in mortality rates[55]. Moreover, there is a certain association between bullying and the risk of adolescent suicide[56]. Bullying is considered a dynamic risk factor for adolescents, as both victims and perpetrators of bullying are at an increased risk of suicide[57]. Lower levels of social connectedness and higher levels of bullying victimization and perpetration are significantly associated with adolescent suicidal ideation and suicide attempts; the relationship between suicidal ideation and bullying victimization also follows a dose-response pattern, with an increased frequency of victimization associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation[58]. Results from a cohort study showed that victims of bullying had more suicide ideation, incidences of self-harm, and suicide attempts across all age groups, with being bullied during adolescence being a strong predictor for suicidal behavior and self-harm[59].

Family factors

The family is considered a significant context for adolescent life and development and is closely linked to mental and physical well-being and future prospects. According to ecosystem theory, the family is a microsystem that profoundly influences individual development, with parenting styles, family relationships and atmosphere, and parental educational levels closely associated with child mental health[60]. Adolescents raised in families with parental mental illness, domestic violence, or abuse have a greater risk of developing mental disorders[61]. On the one hand, there is a certain association between a family history of mental disorders and suicide-related behaviors in adolescents. Studies indicate that the suicide rate among families of suicide victims is twice that of the comparison families, and a family history of suicide can predict suicide independent of severe mental disorders[62]. A psychological autopsy study examining 19 cases of adolescent suicide revealed that 84.2% of the adolescents had a history of mental illness in their family, and 47.4% of the families had a history of suicide, with one adolescent’s father dying from suicide in the year prior to the adolescent’s suicide[63]. On the other hand, a lack of supportive family relationships and environments may act as precipitating risk factors for suicide-related behaviors in adolescents. The extent to which children who are exposed to adversity, including violence, poverty, and disability, can recover depends more on the quality of the environment (rather than on individual characteristics) and the resources available to foster and maintain well-being. Similarly, compared to individual factors, environmental factors have a greater impact on the positive development of individuals exposed to higher levels of stress, such as children who experience abuse[64]. Research suggests that parental support during the relatively psychologically unstable period of adolescence can be crucial in protecting adolescents from the influence of suicidal ideation and promoting the establishment of a positive identity[65]. Therefore, parental and familial support is crucial for adolescent development. If adolescents are already in a relatively psychologically unstable period, face life setbacks or adversities and do not receive material support or emotional care from their families, they are likely to experience severe psychological problems, entertain suicidal thoughts, or even attempt suicide, especially if they experience intense conflicts or severe domestic violence during this critical period.

Individual factors

Sex is considered an important influencing factor in suicide-related behaviors, with males often exhibiting a higher risk of suicide. Taking the following examples of the United States and Hong Kong: Between 2007 and 2014, the suicide rates for males and females in Hong Kong were 18.3 and 9.7 per 100000 population, respectively, with a male-to-female suicide ratio of 1.9. In the United States, the suicide rates for males and females were 21.3 and 5.6 per 100000 population, respectively, with a male-to-female suicide ratio of 3.8[66]. Within the adolescent population, the absolute number of completed suicides and the suicide rate are greater among male adolescents than among female adolescents[67]. Drug abuse, externalizing disorders, and access to means are identified as sex-specific risk factors for suicide death among males[68]. A multigroup comparison study on adolescent suicide and severe suicide attempts revealed a significant association between suicide risk and male sex; the sex difference in suicide outcomes can be explained by method choices, as male suicide victims often employ more direct and lethal methods, such as hanging, vehicle exhaust gas, firearms, and jumping[69]. Moreover, transgender individuals report higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts than does the general population[70]. Sexual orientation is also associated with suicide-related behaviors, with sexual minority males and females having an elevated risk of depression, anxiety, suicide attempts or suicide, and substance-related issues[71]. A survey involving 13984 first-year college students from eight countries and 19 institutions revealed that sexual orientation was the factor most strongly correlated with STBs and the transition from ideation to plan; additionally, no heterosexual students had a greater risk of transitioning from ideation to planned and unplanned attempts[72]. Regarding the reasons for suicide-related behaviors, a survey of 876 self-identified lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth found that for gay, lesbian, and bisexual girls, the stress of coming out was associated with depression and suicidal ideation, and feeling like a burden to the “people in their lives” was identified as a crucial mechanism explaining higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation among LGB youth[73].

Environmental factors

Adolescents spend the majority of their time in school, which serves as a primary setting for their learning and development. Schools provide opportunities for acquiring knowledge, developing skills, and cultivating relationships with teachers and peers. While schools offer unlimited potential for adolescent growth and achievement, they also lead to certain suicide risks. First, the school environment, which includes teacher support, peer support, the teaching and learning atmosphere, and school safety, has a crucial influence on adolescent suicide; negative perceptions of the school environment are significant risk factors for adolescent suicide, as an unfavorable school atmosphere may hinder the fulfillment of basic psychological needs[74]. Additionally, the school environment may increase the availability of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs[20], leading to the emergence of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts among adolescents. Second, there is a correlation between school material conditions and adolescent suicide risk. Underdeveloped material conditions and relative poverty in schools often indicate greater environmental stress, limited developmental resources, and inadequate psychological support. Students from impoverished schools may face greater risks of mental health problems, including suicidal behaviors[75]. Furthermore, while the school environment offers valuable opportunities for peer interaction, it also entails specific group risks such as bullying. Bullying is considered one of the most common expressions of violence among peers during the school year[76]. Physical contact, verbal harassment, rumor spreading, deliberate exclusion of others from the group and obscene gestures are considered important manifestations of bullying[28]. Young people who are not yet fully mature can easily become perpetrators or passive recipients of bullying behaviors due to the interaction of complex interpersonal interactions and family and social environments. For example, a study noted that victimization is associated with poor parental education, low parental occupation and poverty and that victims of bullying are more likely to come from families with a lower socioeconomic status[77]. This in turn creates challenges for the physical and mental health and overall well-being of adolescents. School bullying, as a stepping stone to poor life outcomes, is harmful and repetitive and is a strong risk marker for negative behavioral, health, social and/or emotional problems and is often associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts[78]. For example, during the puberty stage, individuals exposed to verbal bullying, negative rumors and unhealthy interpersonal relationships within schools can present significant self-identity challenges and psychological burdens for adolescents. A survey of 1811 Chinese middle school students revealed a positive correlation between negative rumors in school and suicidal ideation, with the increase in suicidal ideation being mediated by increased academic burnout[79]. Finally, academic performance during the school years is closely associated with adolescent suicide-related behaviors. A systematic study on the relationships between academic stress and adolescent depression, anxiety, self-harm, suicidality, suicide attempts, and suicide demonstrated a positive correlation between academic stress and psychological health issues among adolescents[80]. Suicidal ideation is also significantly associated with depression, test anxiety, academic self-concept, and adolescents’ perceptions of parental dissatisfaction with their academic achievements[81]. In addition to the school environment, sudden environmental changes such as earthquakes, accidental fires, typhoons, tornadoes, hurricanes, mudslides, tsunamis, armed conflicts, particulate pollution, extreme temperatures and humidity, and the COVID-19 pandemic can also influence adolescent suicidal tendencies and risks, including suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, and suicide completion[82,83]. Taking COVID-19 as an example, studies have indicated a 25% increase in suicide attempts among adolescents during the COVID-year, with a particularly significant increase of 195% in suicide attempts among girls during the starting school period[84].

SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL SKILLS AND THEIR IMPORTANT ROLE IN PREVENTING ADOLESCENT SUICIDE

Adolescence is a crucial period of profound physical and psychological change that often leads to certain mental health risks and potential suicidal behaviors; however, this period also has tremendous potential for promoting health and implementing preventive measures that can influence positive health and developmental outcomes[85]. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning defines SEL as the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop self-awareness; manage emotions; achieve personal and collective goals; feel and show empathy; establish and maintain positive relationships; and make responsible and compassionate decisions[34]. Self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making are recognized as the five core SEL skills. As a core aspect of comprehensive student development, SEL fosters empathy, resilience, interpersonal skills, and lifelong learning abilities while supporting academic development and psychological growth, contributing to the development of safe, healthy, and equitable communities[86]. Cultivating and promoting social and emotional skills during adolescence contribute to future well-being and positive life outcomes[87].

Self-awareness

Self-awareness is an individual’s ability to understand his or her own thoughts, emotions, and values and how they influence his or her behavior[88]. Having a healthy level of self-awareness helps adolescents to have a correct understanding of their strengths and weaknesses, maintain a positive and optimistic attitude toward life, and exhibit sufficient self-esteem, self-confidence, and self-love, thereby effectively avoiding the emergence of suicidal thoughts and suicidal behaviors. Self-esteem is considered an individual’s belief about how they perceive themselves and how others perceive them[89]. Self-esteem has a profound impact on adolescents’ suicidal tendencies, as low self-esteem is closely associated with depression, hopelessness, and suicidal tendencies[90]. Findings from a cross-sectional study conducted with 1149 Vietnamese secondary school students demonstrated that[91], compared to students with normal self-esteem, students with low self-esteem had twice the likelihood of experiencing anxiety symptoms and nearly six times the likelihood of being at risk of depression; students with low self-esteem also had a significantly higher probability of considering or attempting suicide. Additionally, optimism, as a highly beneficial psychological trait, is closely related to positive emotions, perseverance, achievements, and physical health[92]. Optimism helps individuals actively cope with difficulties, setbacks, and challenges in life. Self-awareness shows tremendous potential in the prevention of youth suicide. Self-awareness not only helps adolescents maintain a healthy level of self-esteem but also enables them to develop a correct understanding of their sex characteristics, physical and mental conditions, and sexual orientations to better cope with mental health challenges. Self-awareness also guides adolescents to maintain a positive and optimistic attitude toward life in the face of challenges such as major disasters and events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, effectively reducing the risk of suicide.

Self-management

Self-management is an individual’s ability to effectively regulate his or her thoughts, emotions, and behavior in various situations while working toward achieving goals[88]. Self-management encompasses stress management, goal setting, impulse control, self-motivation, and organizational skills and can be utilized to address issues such as hopelessness, anxiety, substance use, and child sexual abuse[32]. Having strong self-management skills helps adolescents take control of their daily lives through goal setting and effective planning, take timely and effective actions in the face of difficulties and setbacks, seek help and support or release stress in times of psychological crisis, and achieve a sense of accomplishment through self-motivation, effectively mitigating the risk of suicide. For example, in the context of academic problems, the transition to higher education brings about changes in the environment, balancing heavy academic loads, tight schedules, and different learning methods; the loss of the comfort zone from childhood; and the fear of not achieving good grades, which often leads to increased stress among adolescents[93]. Under the pressure of such severe stressors, academic problems are often accompanied by negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, hopelessness, and breakdown and are correlated with risky behaviors such as self-harm and suicide[94]. In this context, if adolescents can develop and possess strong self-management skills, they can effectively manage themselves in scientific goal setting, implement effective study plans, adjust their study pace flexibly, and employ appropriate learning motivation. By improving learning efficiency and experiencing academic achievements, adolescents can reduce their psychological issues and lower their risk of suicide.

Social awareness

Social awareness is the ability to understand social perspectives and empathize with individuals from different backgrounds[88]. Having a good level of social awareness enhances adolescents’ empathy, enabling them to consider the viewpoints of other individuals from diverse backgrounds and cultures on the basis of the mastery of social and ethical norms and understanding of social perspectives while also utilizing the resources available in their families, schools, and communities to seek support for their own development. Empathy is associated with positive outcomes such as increased emotional well-being, enhanced social connections, improved health conditions, helping behaviors, cooperation, and altruism[95]. Empathy is negatively correlated with bullying behavior, as understanding and experiencing others’ emotions help children avoid engaging in antisocial behaviors, including bullying; defenders of children who experience bullying also demonstrate a high level of empathy[96]. Families, schools, and communities serve as the primary environments for adolescents’ growth and life experiences; these environments are naturally connected to adolescents and provide diverse material and spiritual resources. These are commonly considered the main settings for implementing interventions related to adolescent suicide prevention[97-99]. For example, a study on racial discrimination and suicidal behaviors among Black adolescents revealed that school safety can reduce suicidal behaviors and moderate the relationship between discrimination and suicide plans and attempts[100]. In light of this, the development of social awareness helps adolescents effectively cope with social risks and impacts. Cultivating empathy reduces bullying and stigmatizing behaviors and guides adolescents to seek help and support from their families, schools, and communities when facing difficulties, effectively reducing the risk of suicide.

Relationship skills

Relationship skills refer to the ability of an individual to develop and maintain healthy and supportive relationships with people from different backgrounds as well as to navigate social situations[88]. Having good interpersonal skills helps adolescents develop various types of relationships by actively listening, communicating in a friendly manner, and collaborating effectively while also resolving conflicts and disagreements with others in a productive manner. Interpersonal interactions are a significant aspect of adolescent life, as adolescents engage and interact with a diverse range of people, including teachers, peers, and parents[101-103]. However, these interactions inevitably bring about interpersonal conflicts and tensions, which may pose a risk of suicidal behavior. A cross-sectional case-control study of 381 Danish adolescents aged 10 to 17 years revealed that having an estranged relationship with parents, siblings, or friends was an early risk factor for suicide, while having problems with parents, boyfriends/girlfriends, or friends accounted for 66%, 17%, and 14.5%, respectively, of all suicide attempts[104]. In this context, fostering relationship skills in adolescents plays a crucial role in the prevention and management of suicide-related behaviors. On the one hand, having good interpersonal skills helps adolescents expand their social networks, with increased interpersonal and emotional support provided by close relationships and interactions. On the other hand, having good interpersonal skills allows adolescents to navigate relationships with their parents, peers, and teachers more effectively, enabling them to resolve interpersonal conflicts constructively and reducing the risk of suicide.

Responsible decision-making

Responsible decision-making refers to the ability of an individual to make caring and constructive social and behavioral choices[88]. Responsible decision-making involves adolescents considering the real-life consequences of their actions based on factors such as personal well-being, others’ feelings, moral standards, and social norms. Suicide, as a highly harmful event, often does not occur abruptly but rather occurs through a certain process. It typically includes crucial points such as suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completion. While there may be connections between these markers, they do not always show continuous progression over time. For instance, research indicates that the majority of individuals with suicidal ideation do not proceed to make suicide attempts[105]. In other words, suicidal thoughts may not always develop into attempted or completed suicide. In this context, responsible decision-making plays a crucial role in adolescent suicide intervention. On the one hand, compared to adults, adolescents often have less mature and comprehensive thinking when considering issues, and they are more prone to impulsivity[104]. “Hot-headed” situations can easily arise, and responsible decision-making can guide adolescents to assess the potential consequences of suicidal behavior based on various real-life considerations, thereby reducing impulsive suicidal acts. On the other hand, responsible decision-making requires adolescents to consider the potential impact on others, social norms, and relevant laws and regulations before engaging in actions. To some extent, responsible decision-making can help curb the occurrence of acts such as school violence, bullying, and stigmatization, ultimately leading to effective intervention by addressing the root causes of suicide risk.

SCHOOL-BASED INTERVENTIONS FOR ADOLESCENT SUICIDE BASED ON SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL SKILLS

The severity of adolescent suicide and the importance of safeguarding adolescent well-being call for more powerful and effective solutions to mitigate this issue. Various interventions, including school-based interventions, community interventions, family interventions, clinical interventions, and digital interventions, have been widely utilized in suicide prevention practices[98,106-108]. School-based interventions based on the school environment are considered robust approaches for implementing health education and addressing suicide risk. Positive school environments, good facilities, friendly social atmospheres, harmonious interpersonal relationships, and professional training programs provide strong support for resolving adolescent suicide issues and have been widely applied in practice. A realist review on the effectiveness of school-based suicide prevention measures highlighted that such interventions can help identify and treat potential mental illnesses, address potential risk factors related to alcohol use, enhance problem-solving abilities, provide support and coping skills, and eliminate cultural barriers and taboos associated with suicide[109]. The integration of social-emotional skills training with school education provides motivation for the resolution of adolescent suicide problems. School-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional competence demonstrate significant potential in the prevention and treatment of adolescent suicide.

First, school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional skills are appropriate for addressing the crisis of adolescent suicide. As one of the microsystems where adolescents are situated, school has the most direct influence on adolescent development[110]. Adolescents spend a significant portion of their adolescence in the school environment, where they learn, socialize, and grow, acquiring various interpersonal skills. Therefore, the cultivation and improvement of social-emotional competence are crucial and inevitable outcomes of school life. The development of social-emotional competence and the resulting improvements in interpersonal relationships and psychological support within the school environment can enhance adolescents’ sense of well-being to a certain extent, thereby preventing the emergence of psychological problems and reducing the risk of suicide. On the other hand, educators, school support staff, and peers are well positioned to identify and address risk factors and emerging mental health issues in adolescents, linking them to resources[85], including social-emotional learning programs. This allows real-time monitoring of adolescent suicide risk factors and enables timely intervention and guidance based on appropriate social-emotional competence when suicide risk is detected or when suicidal behaviors occur.

Furthermore, the necessity of school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional skills in addressing the crisis of adolescent suicide should be emphasized. Given the high severity of adolescent suicide status and the significant harm caused by suicidal outcomes, school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional competence require a high level of professionalism and precision. Haphazardly or superficially implemented interventions may not only fail to enhance adolescents’ social-emotional competence and dispel suicidal thoughts but also might even have adverse effects, further exacerbating their mental conditions or increasing their risk of suicidal behaviors. Against this backdrop, schools have become crucial settings for implementing school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional competence. Professional staff[111,112] can develop relatively comprehensive suicide prevention plans, provide systematic courses on social-emotional learning, and conduct scientific, reasonable, and targeted social-emotional learning for adolescents. Moreover, they can provide suitable platforms for social-emotional competence training and practice. By implementing scientifically designed curricula and providing professional training, schools can effectively promote the practical enhancement of adolescents’ social-emotional competence and improve their mental well-being, thus facilitating efficient interventions for adolescent suicide.

Additionally, school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional skills are cost effective and comprehensive for addressing the crisis of adolescent suicide. From an economic perspective, school-based suicide prevention and mental health education programs are considered efficient and cost-effective approaches to youth education[113]. As representatives of educational institutions, schools naturally possess professional teams, program curricula, and physical facilities for conducting adolescent suicide interventions. They also provide a platform for learning and communication to cultivate adolescents’ social-emotional competence. Therefore, implementing school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional competence does not require the construction of new platforms or organizational development. Concentrated and efficient suicide interventions can be provided for adolescents while minimizing manpower, material, and time costs. From a comprehensive perspective, schools play a crucial intermediary role in connecting families and society. On the one hand, societal demands are conveyed to students through schools, and it is through schools that the plans and programmes for adolescent suicide intervention can truly materialize. On the other hand, families and schools are cooperative partners, and schools can, to some extent, regulate pressure from families, providing potential opportunities for adolescents to escape from negative parenting[114].

Finally, school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional skills are effective at addressing the crisis of adolescent suicide. Social-emotional skills are associated with important social, behavioral, and academic outcomes for healthy development. Social-emotional skills not only predict significant life outcomes in adulthood but can also be improved through feasible and cost-effective intervention measures[33]. School-based SEL programmes have been shown to enhance students’ abilities. The effective implementation of evidence-based SEL programs can lead to measurable and potentially long-lasting improvements in various aspects of children’s lives[115], including improvements in mental well-being and a reduction in suicide risk, which has been acknowledged by the academic community. For example, in response to a series of suicide tragedies in 2015, Tooele County Public Schools in Utah implemented evidence-based SEL curricula in all elementary and junior high schools. Two years later, while youth suicidality rates continued to rise in other counties in the state, the youth suicidality rate in Tooele County actually declined[32]. A meta-analysis involving 213 school-based universal SEL programs and 270034 kindergarten-to-high school students showed that, compared to control groups, the SEL program group demonstrated significant improvements in social and emotional skills, attitudes, behavior, and academic performance, with an 11 percentage point increase in achievement[116]. Similarly, a meta-analysis of 82 school-based universal SEL interventions involving 97406 kindergarten-to-high school students showed that SEL interventions can promote positive development in adolescents. Participants in the intervention group had significantly better social-emotional skills, attitudes, and indicators of well-being than did those in the control group. Additionally, SEL interventions had consistent positive effects on students from different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds, as well as domestic and international student populations[117]. In this context, school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional competence are considered realistic and effective approaches for addressing the crisis of adolescent suicide. These interventions led to enhanced social and emotional skills, improved academic performance, an increased sense of happiness, increased prosocial behaviors, reduced behavioral and internalizing problems, and alleviated mental health conditions, providing new opportunities for reducing adolescent suicidal behavior and ultimately resolving the issue of adolescent suicide.

CONCLUSION

Suicide poses a significant threat to individuals’ physical and mental health, life safety, social well-being and even regional development. Adolescents are considered one of the groups most affected by suicide. Given the severity of the current situation and the urgency of addressing adolescent suicide, this article systematically reviewed the risk factors for adolescent suicide and analyzed the important role of social-emotional learning in suicide prevention and intervention. It also explored school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional skills. Psychological, social, family, individual, and environmental factors are important risk factors for adolescent suicidal behaviors. Social-emotional learning is regarded as a powerful intervention measure for addressing and preventing adolescent suicide. The five core competencies of social-emotional learning, namely, self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making, have been shown to effectively address various suicide risks among adolescents and provide necessary protection against suicidal behaviors. Among the various suicide intervention methods, school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional skills have shown immense potential in preventing and addressing adolescent suicide. These methods are appropriate, necessary, cost effective, comprehensive, and effective at tackling the crisis of adolescent suicide. These interventions, which promote enhanced social and emotional skills, improved academic performance, increased happiness, increased prosocial behaviors, reduced behavioral and internalizing problems, and the alleviation of mental health conditions, provide new hope for reducing adolescent suicidal behaviors and ultimately resolving the issue of adolescent suicide.

To further unleash the potential of school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional competence and better address the issue of adolescent suicide, further promotion measures are recommended in the following areas. First, adequate funding support should be provided. While school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional skills are cost effective and can minimize manpower, resources, and time costs, continuous improvement in adolescent suicide effectiveness requires ongoing project adjustments, curriculum reforms, facility development, platform building, and gatekeeper training within schools. These activities require sufficient funding support to ensure steady operation. Second, the combination of social-emotional learning and other suicide prevention programs within schools should be fostered to avoid fragmentation in suicide intervention efforts. While school-based interventions for adolescent suicide based on social-emotional skills are effective at addressing the crisis of adolescent suicide, the importance of other suicide prevention approaches should not be overlooked. Only through mutual collaboration and cooperation can the effectiveness and comprehensiveness of adolescent suicide interventions be fully promoted. Finally, synergies among schools, families, society, and other environments should be fully leveraged. In addition to the school environment, families and society are important places for the development of social-emotional skills in adolescents. Therefore, schools should strengthen cooperation with other parties, expand the scope of social-emotional learning spaces, jointly develop social-emotional learning curricula, and build social-emotional learning platforms to promote collective effort in adolescent suicide prevention. This collaboration will enable better resolution of suicide issues on the “last mile” based on resource sharing and personnel cooperation.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Salvadori M, Italy S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao YQ