Published online Feb 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i2.296

Peer-review started: October 19, 2023

First decision: December 11, 2023

Revised: December 15, 2023

Accepted: January 18, 2024

Article in press: January 18, 2024

Published online: February 19, 2024

Processing time: 109 Days and 23.1 Hours

Most studies have defined economic well-being as socioeconomic status, with little attention given to whether other indicators influence self-esteem. Little is known about racial/ethnic disparities in the relationship between economic well-being and self-esteem during adulthood.

To explore the impact of economic well-being on self-esteem in adulthood and differences in the association across race/ethnicity.

The current study used data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979. The final sample consisted of 2267 African Americans, 1425 Hispanics, and 3678 non-Hispanic Whites. Ordinary linear regression analyses and logistic regression analyses were conducted.

African Americans and Hispanics were more likely to be in poverty in compa

The role of employers is important in cultivating employees’ self-esteem. Satis

Core Tip: Little is known about racial/ethnic disparities in the relationship between economic well-being and self-esteem during adulthood. Findings from this study expand on prior research in several ways: Focusing on adults’ self-esteem rather than adolescents, looking at racial/ethnic disparities in self-esteem among adults, better understanding of economic well-being by including factors that have not been addressed in previous studies, and examining racial/ethnic disparities in the relationship between economic well-being and self-esteem.

- Citation: Lee J. Disparities in the impact of economic well-being on self-esteem in adulthood: Race and ethnicity. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(2): 296-307

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i2/296.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i2.296

Self-esteem is an important factor for achievement in the workplace[1,2]. Specifically, individuals with higher self-esteem were more likely to have characteristics that directly contribute to successful performance in the labor market[2-4]. Levels of self-esteem were documented as changing over the life course[5], with the highest levels of self-esteem reported just before entering into older adulthood, followed by a rapid decrease in later years[1,6]. The reasons for these changes can be attributed partially to the level of economic well-being[7]. For instance, individuals with low socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds reported lower levels of self-esteem during childhood[8]. However, little attention has been given to examining whether other aspects of economic well-being, aside from SES, may impact self-esteem during adulthood. Furthermore, little is known about how aspects of economic well-being beyond standard measures of SES (e.g., poverty and employment), such as job satisfaction and fringe benefits, influence self-esteem; the majority of this work has focused primarily on the influence of economic well-being on self-esteem in adolescence or childhood rather than adulthood[3,5].

Racial/ethnic disparities in the association between economic well-being and self-esteem also exist. Research has shown that African Americans are more likely to have greater self-esteem than Whites and Hispanics[9], while Hispanics were less likely to have higher levels of self-esteem in comparison with Whites[10]. In terms of economic well-being, African Americans were less likely to be employed[11] and more likely to be exposed to disadvantages in income and assets[12]. For instance, rates of unemployment among African Americans were approximately twice those of Whites[13]. Given differences in levels of self-esteem and economic well-being across racial/ethnic groups, it is necessary to identify how race/ethnicity may moderate the relationship between economic well-being and self-esteem. Thus, the present study explores whether other aspects of economic well-being, aside from SES, influence self-esteem among adults and investigates whether any racial/ethnic disparities exist in this relationship.

Self-esteem refers to values and beliefs about oneself, as well as individual self-assessment[5,14]. Levels of self-esteem have a direct association with physical and mental health outcomes. For instance, individuals with low levels of self-esteem were more likely to experience poor physical and mental health[2-4,15].

When it comes to factors that affect self-esteem, race/ethnicity has been shown to have a greater effect than other demographic characteristics[5], making race/ethnicity an important factor in understanding racial/ethnic differences in self-esteem[16]. For example, Hispanics showed lower levels of self-esteem in comparison with non-Hispanic Whites[10,17]. Conversely, African Americans in the United States reported higher self-esteem when compared to non-Hispanic Whites[5,18]. While the gap between these different levels of self-esteem across racial/ethnic groups is not large in childhood, it increases, based on racial/ethnic disparities, with age[10].

Individuals with higher self-esteem tend to be proud of themselves regardless of their performance feedback and tend not to be ashamed of poor performance[18]. As such, they are more likely to adapt to a workplace even if they make mistakes while working, leading them to have better resilience and productivity. On the other hand, people with low self-esteem were likely to suffer from work-related problems[2]. In other words, higher self-esteem in adulthood is critical to adjust workplace and produce better performance and productivity in society. Given that previous research has mainly addressed self-esteem before adulthood, the current study expands on the range of age in its investigation on self-esteem by focusing on adults.

Economic well-being is a broad concept and can roughly be defined as economic hardship; difficulties, or challenges, such as trouble paying bills, dissatisfaction with individual economic resources; and an inability to meet basic household needs such as clothing, food, housing, and health services[19]. Economic strains greatly increase levels of stress and can pose threats to daily life and basic needs[20]. Individuals who have unsatisfied needs regarding their economic resources are more likely to suffer from stresses due to their poor economic well-being, leading them to feel a sense of uncertainty and unhappiness. Thus, individuals with poor economic well-being often experience difficulties in developing higher self-esteem due to feelings of hopelessness or desperation.

Racial/ethnic disparities have a close relationship with socioeconomic inequalities[21]. Hispanics are exposed to higher risks of chronic financial hardship due to accumulated limitations in education, employment, and access to resources[22]. Hispanics also experienced higher rates of poverty than non-Hispanic Whites[23]. African Americans tended to have lower levels of economic well-being due to racial discrimination compared to non-Hispanic Whites[24] and other factors which can lead to fewer opportunities for employment[11]. Conversely, non-Hispanic White men and women were less likely to live in poverty in comparison with African American, Hispanic, and Asian men and women[25].

As a result of economic disparities, racial/ethnic minorities with low levels of economic well-being may be more at risk for low self-esteem[7] due to limited resources, higher rates of unemployment, and lower economic status in comparison with non-Hispanic Whites. Thus, it is necessary to examine racial/ethnic disparities in economic well-being and whether these disparities negatively influence self-esteem.

Given that previous research regarding economic well-being has mainly addressed income-related factors such as poverty and employment, which are considered objective factors[26], it is necessary to shift the perspective from objective economic well-being to subjective economic well-being because well-being should be measured by self-evaluation of one’s economic status. Subjective well-being refers to a broad concept of life satisfaction[27], with subjective factors influencing quality of life and mental health[28]. Therefore, the current study seeks to expand the concept of economic well-being to include objective factors such as employment status, poverty level, and presence of work-related fringe benefits (such as employment-based benefits including health insurance, life insurance, and paid vacation), as well as the subjective factor of job satisfaction.

In terms of objective factors, unemployment has been linked to a sense of helplessness and mental illnesses, both of which discourage individuals from engaging in productive activities[29]. Research has shown that joblessness is associated with decreased personal efficacy and lower levels of self-esteem[30]. Furthermore, individuals who are unemployed for extended periods of time are at an even greater risk for low self-esteem[31]. Unemployment can lead to a sense of losing control of one’s life due to concerns about potential unemployment and the uncertainty of one’s living and financial situation[32]. In addition to unemployment, as poverty has an impact on lives across the life course[33], people who had often been exposed to poverty showed a higher prevalence of depression or suffer from poorer mental health[34]. As a result of mental health problems, individuals in poverty may be more likely to have poor self-esteem.

Given workers’ well-being has become critical in achieving economic development and improving individuals’ satisfaction with their lives[35], fringe benefits enhancing individuals’ satisfaction with their jobs should be considered in relation to their well-being. In the workplace, individuals with better financial planning may be more likely to have higher levels of self-esteem. For example, individuals with a retirement plan as part of their fringe benefits were likely to develop greater self-esteem due to financial assistance in later life[36]. While previous research has mainly addressed the effects of unemployment or poverty as predictors of self-esteem, less is known about the relationship between subjective factors of economic well-being and self-esteem in adulthood.

As a subjective factor, levels of job satisfaction can also influence self-esteem. Psychological stressors from the workplace arise from a lack of support from supervisors, job strain, or job insecurity[37]. As some of these stressors are attributed to individuals’ differing perceptions of their jobs, levels of job satisfaction may either positively or negatively influence their mental health. Research has identified relationships between mental health and job satisfaction[38,39]. For example, employees who consider themselves unemployed are more likely to have poor physical and mental health[40], while those who are employed and suffer less from work-related stresses may be satisfied with their work situation. In addition, job strains, which result from subjective perceptions of one’s workload and workplace support, can also impact psychiatric morbidity negatively[41].

African Americans may be more likely to have lower self-esteem in comparison with Whites. This disparity can be explained by the influence of negative perceptions of minority groups by the majority culture. In other words, because African Americans in the United States are stigmatized as a minority group, they tend to have poor self-esteem compared with Whites[42]. Furthermore, racial majority, referring to non-Hispanic Whites, are less likely to report poor self-esteem than minority groups[18]. When African Americans compare their poor resources and lower SES to their non-Hispanic White counterparts, this can lead to a negative self-perception as disadvantaged and inferior in comparison to Whites[5]. However, racial/ethnic disparities in self-esteem have not been consistent[9]. Little empirical evidence exists to support the inconsistent findings during adulthood. Therefore, further exploration is needed to determine whether risk factors that lead to low self-esteem differ across racial/ethnic groups.

Given that different levels of self-esteem across individuals and racial/ethnic groups may lead to disparities in quality of life, exploring which factors contribute to unequal levels of self-esteem should be investigated. The research questions in this study are as follows: (1) Are there racial/ethnic disparities in economic well-being after controlling for individual characteristics? (2) How does economic well-being influence self-esteem? and (3) Does this association differ across race/ethnicity? We hypothesize that: (1) There are racial/ethnic disparities in poverty, employment, fringe benefits, and job satisfaction; (2) Economic well-being (employment, poverty, fringe benefits, and job satisfaction) influences self-esteem; and (3) Race/ethnicity moderates the relationship between economic well-being and self-esteem. Findings from this study expand on prior research in several ways: Focusing on adults’ self-esteem rather than adolescents, looking at racial/ethnic disparities in self-esteem among adults, better understanding of economic well-being by including factors that have not been addressed in previous studies, and examining racial/ethnic disparities in the relationship between economic well-being and self-esteem.

The primary data source for the proposed study is the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79), which was conducted by the United States Department of Labor. The NLSY79 is a nationwide representative data set of 12686 participants living in the United States whose ages ranged from 14 to 22 years back in 1979, when the survey was first conducted. The NLSY79 participants have been re-interviewed annually from 1979 through 1994 and biennially since then. The initial response rate was approximately 90% with retention rates over 90% in the first 16 waves, and the rates in subsequent waves were over 80%. The NLSY79 measured self-esteem in 1980, 1987, and 2006. The current study uses data from the NLSY79 for the year 2006, which is the latest wave of the NLSY79 available, to access findings related to self-esteem in order to explore the effect of economic well-being on self-esteem. The final sample from the 2006 wave consists of 2267 African Americans, 1425 Hispanics, and 3678 non-Hispanic Whites, and those who were not interviewed (non-interview) or refused to be interviewed were excluded from the study. Of the 7370 participants, males made up 48.7% (3589) while females accounted for 51.3% (3781).

Self-esteem: The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was used to measure respondents’ self-esteem. The scale illustrates a level of approval or disapproval toward oneself[43]. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale consists of 10 items with a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree). Five items were reversed prior to using the scale for analysis. All items were summed with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem (range 5-30; mean ± SD = 23.48 ± 4.45).

Poverty: Poverty indicates whether individuals’ total family income was above or below the poverty level. The poverty variable was classified into two groups: Those who were above the poverty level (coded = 0) and those who were below the poverty level (coded = 1).

Job satisfaction: Respondents were queried about their levels of job satisfaction regarding up to five jobs. Respondents were asked how they felt about current/recent jobs with a four-point scale ranging from 1 (very like) to 4 (very dislike). All items concerning jobs were reverse-scored prior to conducting the analysis, with a higher score indicating higher satisfaction with their jobs. Total job satisfaction scores were computed by calculating the mean of individual items (range 1-4; mean ± SD = 3.36 ± 0.65).

Employment: Respondents reported their employment status by answering one of the following conditions: Employed, unemployed, out of labor force, or in active forces. The respondents were classified into two groups: Those who were employed (coded = 1) and those who were not (coded = 0).

Respondents answered yes/no about whether they received any of nine fringe benefits from up to five of their jobs: Hospital and life insurance, paid vacation and sick days, dental benefits, maternity/paternity leave, retirement plans, profit sharing, training, childcare, and flexible work schedule hours. The respondents answered either yes (coded = 1) if they had ever received the benefits or no (coded = 0) if they had not. Total fringe benefits were computed by adding all answers (range 0-35; mean ± SD = 6.18 ± 3.76).

Demographics variables were included as covariates in this study as follows: Age, gender, education, urban/rural residence, and marital status.

Ordinary linear regression analyses and logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine whether there are racial/ethnic disparities in economic well-being after controlling for individual characteristics. Ordinary linear regression analyses tested whether economic well-being influences self-esteem and if this association differs across race/ethnicity.

Table 1 indicates racial/ethnic differences in variables used in the current study. Hispanics reported lower levels of self-esteem than African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. With respect to economic well-being, African Americans were more likely to receive fringe benefits than Hispanics. On the other hand, Hispanics indicated higher job satisfaction compared with African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. Both African Americans and Hispanics were vulnerable to low levels of income: They were more likely to be in poverty and unemployed and received less education than non-Hispanic Whites. In addition, both African Americans and Hispanics were less likely to be currently married in comparison with non-Hispanic Whites.

| Variables | African American (n = 2267), % | Hispanic (n = 1425), % | Non-Hispanic White (n = 3678), % | Total (n = 7370) | P value |

| Self-esteem | 23.66 (4.48) | 22.91 (4.48) | 23.59 (4.41) | 23.48 (4.45) | a,c |

| Economic well-being | |||||

| Fringe benefits | 6.40 (4.06) | 5.95 (3.82) | 6.12 (3.55) | 6.18 (3.76) | a |

| Job satisfaction | 3.32 (0.67) | 3.41 (0.63) | 3.36 (0.65) | 3.36 (0.65) | a,c |

| Poverty | 24.1 | 17.1 | 7.7 | 14.5 | a,b,c |

| Employment | 74.7 | 78.0 | 83.4 | 79.7 | a,b,c |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (yr) | 44.57 (2.22) | 44.50 (2.25) | 44.58 (2.27) | 44.56 (2.25) | |

| Gender (male) | 49.0 | 49.5 | 48.2 | 48.7 | |

| Education (non-higher education) | 73.1 | 74.6 | 56.8 | 65.2 | b,c |

| Urban resident | 85.7 | 89.1 | 67.6 | 77.3 | a,b,c |

| Marital status (marriage) | 35.5 | 54.3 | 67.4 | 55.1 | a,b,c |

Findings for research question 1: Are there racial/ethnic disparities in economic well-being after controlling for individual characteristics?

As shown in Model 1 of Table 2, African Americans were more likely to receive fringe benefits than non-Hispanic Whites (β = 0.33, t = 2.70, P < 0.01). There were no significant disparities between Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites. Model 2 of Table 2 indicated that the racial/ethnic disparities in fringe benefits between African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites remained significant (β = 0.52, t = 0.06, P < 0.001) after controlling for demographics. Individuals with higher education (β = -1.12, t = -10.09, P < 0.001, living in urban areas (β = 0.52, t = 3.97, P < 0.001), and who were married (β = 0.42, t = 3.81, P < 0.001) were more likely to receive the fringe benefits. On the other hand, Hispanics had higher levels of job satisfaction in comparison with non-Hispanic Whites (β = 0.05, t = 2.27, P < 0.05). When demographic variables were entered into the model, Hispanics remained significant, indicating greater job satisfaction compared with non-Hispanic Whites (β = 0.07, t = 2.98, P < 0.01). Respondents who had higher education and were married were more satisfied with their jobs (β = -0.06, t = -3.15, P < 0.01; β = 0.09, t = 4.65, P < 0.001).

| Variables | Economic well-being | |||

| Fringe benefits | Job satisfaction | |||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| (Constant) | 6.12 (0.07) | 6.06 (1.05) | 3.35 (0.01) | 3.24 (0.18) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 0.33 | 0.52 | -0.03 | 0.00 |

| (0.12) | (0.13) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| [0.04]b | [0.06]c | [-0.02] | [0.00] | |

| Hispanic | -0.06 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| (0.14) | (0.15) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| [-0.01] | [0.01] | [0.03]a | [0.04]b | |

| Ages | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| (0.02) | (0.00) | |||

| [0.00] | [0.01] | |||

| Gender (male) | -0.02 | -0.02 | ||

| (0.11) | (0.02) | |||

| [-0.00] | [-0.02] | |||

| Education (non-higher education) | -1.12 | -0.06 | ||

| (0.11) | (0.02) | |||

| [-0.15]c | [-0.04]b | |||

| Residence (urban) | 0.52 | 0.01 | ||

| (0.13) | (0.02) | |||

| [0.06]c | [0.01] | |||

| Marital status (marriage) | 0.42 | 0.09 | ||

| (0.11) | (0.02) | |||

| [0.06]c | [0.07]c | |||

Table 3 indicates racial/ethnic disparities in poverty and employment. Both African Americans [β = 1.40, Wald = 242.12, odds ratio (OR) = 4.05, P < 0.001] and Hispanics (β = 0.84, Wald = 57.94, OR = 2.30, P < 0.001) were more likely to be in poverty in comparison with non-Hispanic Whites (Model 1). The significant differences remained after controlling for demographics (Model 2). More African Americans (β = -0.56, Wald = 60.81, OR = 0.57, P < 0.001) and Hispanics (β = -0.30, Wald = 11.73, OR = 0.74, P < 0.01) were unemployed than non-Hispanic Whites (Model 1). As demographics were entered into the model, these disparities remained significant between African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites (β = -0.27, Wald = 11.38, OR = 0.77, P < 0.01) while there was no significant association between Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites. Females were more likely to be in a low-income family (β = -0.53, Wald = 39.12, OR = 0.59, P < 0.001) and be unemployed compared to males (β = 0.53, Wald= 62.83, OR = 1.70, P < 0.001). In addition, individuals with low levels of education were significantly associated with poverty (β = 1.34, Wald = 126.70, OR = 3.82, P < 0.001) and unemployment (β = -0.76, Wald = 92.81, OR = 0.47, P < 0.001). Lastly, married individuals were less likely to end up in poverty (β = -2.01, Wald = 348.81, OR = 0.13, P < 0.001) or be unemployed (β = 0.58, Wald = 70.44, OR = 1.79, P < 0.001).

| Variables | Economic well-being | |||||||

| Poverty | 95%CI | Employment | 95%CI | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| (Constant) | -2.56 (0.07) | -3.10 (0.85) | Lower | Upper | -3.45 (2.35) | 1.96 (0.66) | Lower | Upper |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| African American | 1.40 | 0.83 | 1.89 | 2.80 | -0.56 | -0.27 | 0.66 | 0.89 |

| (242.12) | (69.73) | (60.81) | (11.48) | |||||

| [4.05]c | [2.30]c | [0.57]c | [0.77]b | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.84 | 0.54 | 1.36 | 2.18 | -0.30 | -0.90 | 0.76 | 1.09 |

| (57.94) | (20.22) | (11.73) | (1.03) | |||||

| [2.30]c | [1.72]c | [0.74]b | [0.91] | |||||

| Ages | 0.02 | 0.99 | 1.06 | -0.01 | 0.96 | 1.02 | ||

| (1.49) | (0.37) | |||||||

| [1.02] | [0.99] | |||||||

| Gender (male) | -0.53 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 1.19 | 1.94 | ||

| (39.12) | (62.83) | |||||||

| [0.59]c | [1.70]c | |||||||

| Education (non-higher education) | 1.34 | 3.02 | 4.82 | -0.76 | 0.40 | 0.55 | ||

| (126.70) | (92.81) | |||||||

| [3.82]c | [0.47]c | |||||||

| Residence (urban) | -0.35 | 0.57 | 0.87 | -0.02 | 0.83 | 1.15 | ||

| (10.62) | (0.07) | |||||||

| [0.71]b | [0.98] | |||||||

| Marital status (marriage) | -2.01 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.58 | 1.56 | 2.05 | ||

| (348.81) | (70.44) | |||||||

| [0.13]c | [1.79]c | |||||||

Findings for research question 2: How does economic well-being influence self-esteem and does this association differ across race/ethnicity?

As shown in the Table 4, there were significant racial/ethnic differences in self-esteem. Model 1 indicated that African Americans were more likely to have greater levels of self-esteem compared with non-Hispanic Whites (β = 0.26, t =1.85, P < 0.1). Model 2 showed that the racial/ethnic disparities between African Americans’ and non-Hispanic Whites’ self-esteem remained significant (β = 0.67, t = 4.53, P < 0.001) after controlling for demographics. Model 3 indicated that African Americans’ elevated levels of self-esteem significantly persisted even after controlling for economic well-being (β = 0.70, t = 4.72, P < 0.001). Males were more likely to have greater self-esteem (β = 0.27, t = 2.21, P < 0.05). Having less education (β = -1.21, t = -9.34, P < 0.001) was negatively associated with self-esteem, while being married (β = 0.45, t = 3.42, P < 0.01) was positively associated with self-esteem.

| Variables | Self-esteem | |||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| (Constant) | 23.78 (0.09) | 24.54 (1.23) | 21.37 (1.26) | 20.16 (1.30) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 0.27 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 3.02 |

| (0.14) | (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.74) | |

| [0.03]a | [0.07]d | [0.08]d | [0.33]d | |

| Hispanic | -0.35 | -0.05 | -0.10 | 1.70 |

| (0.17) | (0.17) | (0.17) | (0.92) | |

| [-0.03]b | [-0.01] | [-0.01] | [0.16]a | |

| Ages | -0.02 | -0.02 | -0.02 | |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.03) | ||

| [-0.01] | [-0.01] | [-0.01] | ||

| Gender (male) | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.29 | |

| (0.12) | (0.12) | (0.12) | ||

| [0.03]b | [0.03]b | [0.04]b | ||

| Education (non-higher education) | -1.43 | -1.21 | -1.19 | |

| (0.13) | (0.13) | (0.13) | ||

| [-0.16]d | [-0.14]d | [-0.14]d | ||

| Residence (urban) | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.15) | ||

| [0.01] | [0.00] | [0.00] | ||

| Marital status (marriage) | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0.42 | |

| (0.13) | (0.13) | (0.14) | ||

| [0.08]d | [0.05]c | [0.05]c | ||

| Economic well-being | ||||

| Fringe benefits | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||

| (0.02) | (0.02) | |||

| [0.06]d | [0.06]d | |||

| Job satisfaction | 0.77 | 1.10 | ||

| (0.09) | (0.13) | |||

| [0.12]d | [0.17]d | |||

| Poverty | -1.25 | -1.23 | ||

| (0.24) | (0.24) | |||

| [-0.08]d | [-0.08]d | |||

| Employment | 0.56 | 0.57 | ||

| (0.23) | (0.23) | |||

| [0.04]b | [0.04]b | |||

| Fringe benefits X, African American | 0.13 | |||

| (0.07) | ||||

| [0.05]a | ||||

| Fringe benefits X, Hispanic | -0.14 | |||

| (0.09) | ||||

| [-0.05] | ||||

| Job satisfaction X, African American | -0.81 | |||

| (0.21) | ||||

| [-0.30]d | ||||

| Job satisfaction X, Hispanic | -0.40 | |||

| (0.26) | ||||

| [-0.13] | ||||

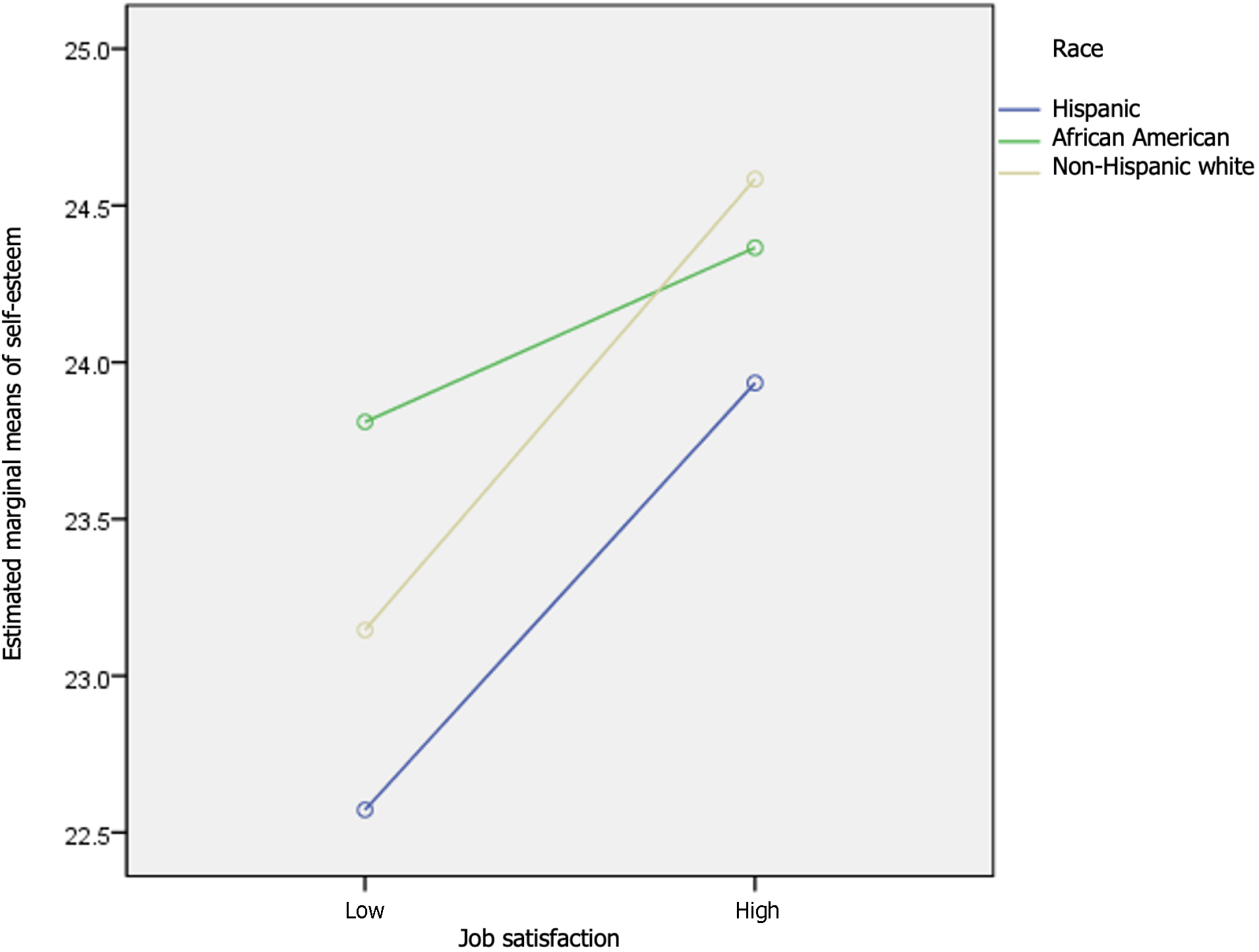

With respect to economic well-being, those who received fringe benefits (β = 0.07, t = 3.90, P < 0.001) were more satisfied with their jobs (β = 0.77, t = 8.28, P < 0.001), and those who were employed (β = 0.56, t = 2.46, P < 0.05) were more likely to have higher levels of self-esteem. Poverty was negatively associated with self-esteem (β = -1.25, t = -5.23, P < 0.001). Interaction effects were found between African Americans and fringe benefits predicting self-esteem (β = 0.13, t = 1.78, P < 0.10) and African Americans and job satisfaction predicting self-esteem (β = -0.81, t = -3.86, P < 0.001). As shown in Figure 1, self-esteem among African Americans was less influenced by job satisfaction than it was among non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanics. The gap between those who were less satisfied with jobs and those who more satisfied with jobs among African Americans (0.56) was smaller than that among non-Hispanic Whites (1.43) and Hispanics (1.36).

The findings of this study suggest evidence of important racial/ethnic disparities both in economic well-being and self-esteem for adults. In terms of economic well-being, African Americans were more likely to be in poverty and be unemployed in comparison with non-Hispanic Whites and received significantly greater fringe benefits than their counterparts. Hispanics were at greater risk of unemployment compared with non-Hispanic Whites; however, they were more satisfied with their jobs than non-Hispanic Whites. Also, African Americans reported higher self-esteem compared with non-Hispanic Whites. With regard to the relationship between economic well-being and mental health, those who received fringe benefits were more satisfied with jobs, and those who were employed reported higher levels of self-esteem. Furthermore, poverty was negatively associated with self-esteem. Interaction effects were found: African American ethnicity moderates the relationship between fringe benefits and self-esteem, as well as the relationship between job satisfaction and self-esteem.

In terms of income-related factors, findings among African Americans and Hispanics are consistent with previous research indicating lower levels of economic well-being across racial/ethnic minority populations[23,24], with results showing higher rates of unemployment and poverty in these groups. However, although they are less likely to be employed compared to non-Hispanic Whites, the findings from this study provide evidence that African Americans are more protected by fringe benefits compared to non-Hispanic Whites once they are employed.

While there are no studies that focus specifically on racial/ethnic disparities using a comprehensive measure of fringe benefits, previous work has shown that minorities are less likely to have employer-sponsored health plans[44], a form of fringe benefits. In addition, African Americans and Hispanics are less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to have health insurance, and uninsured minorities tend not to buy private insurance compared with uninsured non-Hispanic Whites. Our study adds to this literature by showing that, with a more comprehensive measure of fringe benefits, African Americans report higher fringe benefits than non-Hispanic Whites. As African Americans are more likely to have lower SES compared with non-Hispanic Whites, they may actively seek out jobs that provide employer-based benefits in order to supplement a lack of access to health insurance. These efforts may be related to the findings that they received more fringe benefits than non-Hispanic Whites, who may seek fringe benefits less often due to higher income. In other words, fringe benefits may play a role as an alternative to social insurance or social safety nets by covering some parts of social benefits.

Hispanics may be likely to commit to their workplace compared to their counterparts due to greater levels of job satisfaction. Furthermore, as minorities with greater job satisfaction may be more productive in the workplace, their work may result in greater performance and contribute to a more productive society. In other words, impacts of employment may be much more extensive in Hispanics. As such, increasing levels of job satisfaction is important to improve the quality of minorities’ lives while also building a productive workplace.

In terms of self-esteem, consistent with prior studies that African Americans reported greater levels of self-esteem[5,10], this study also shows African Americans reporting higher self-esteem. This result provides further evidence that racial/ethnic differences in self-esteem have continued from adolescence to adulthood. Previous research has mainly addressed self-esteem among adolescents rather than adults[2,3,5]. However, given that adulthood is another stage of life entering into new environments and tasks, self-esteem is still important in understanding adulthood as self-esteem influences individuals’ success or performance[2]. In particular, as most individuals are employed when they become adults, it is necessary to examine how economic factors influence their self-esteem. On the other hand, this study demonstrates the associations between economic factors and self-esteem among adults. Consistent with previous studies[30,31], findings indicate that unemployed individuals and those in poverty are more likely to have poor self-esteem. In addition, those who received more fringe benefits and are more satisfied with their jobs are more likely to develop greater levels of self-esteem. Given that little is known about the relationship between economic well-being, which is affected by factors such as job satisfaction and fringe benefits, and self-esteem, findings of the current study shed light on the importance of examining economic factors other than just poverty or employment, which were the primary focus of earlier research. In particular, because we found that individuals with higher job satisfaction and greater support from their workplace have better self-esteem, and workers with greater self-esteem are more likely to perform better work, employers should be encouraged to create a positive environment in the workplace and expand the benefits they offer to employees.

Findings from this study reveal that African Americans moderate the relationships between job satisfaction and self-esteem. Job satisfaction among African Americans had less of an effect on increasing self-esteem, whereas job satisfaction had a great impact on increasing levels of self-esteem among non-Hispanic Whites. Generally, greater numbers of non-Hispanic Whites already meet their basic needs through sufficient income than African Americans, and, as such, they do not need to receive benefits to maintain their daily lives because their physiological needs are more satisfied than those of African Americans. Consequently, satisfactory outcomes or feelings of happiness from the workplace may be more important to them, while African Americans may seek out tangible benefits rather than personal satisfaction with their jobs. For these reasons, fringe benefits have a greater effect on the self-esteem of African Americans, while job satisfaction has a greater effect on the self-esteem of non-Hispanic Whites. These findings offer further evidence that employment-based benefits are critical to increase levels of self-esteem for African Americans who have entered into labor markets and job satisfaction is more important for non-Hispanic Whites’ self-esteem in adulthood.

Although the current study provides important information on the relationships between economic well-being and self-esteem in the context of race/ethnicity, the findings from this study should be interpreted in the context of limitations. The proposed study was conducted by ordinary linear regression and logistic regression even though the NLSY79 measured self-esteem throughout three separate waves for a longitudinal study: 1980, 1987, and 2006. Given that few respondents might be employed in the labor market before their early 20s, it is not reasonable to consider economic well-being factors in 1980 and 1987. However, given that it is limited to capturing the complexity of the relationship between economic well-being and self-esteem, further study should use longitudinal data set to identify the cumulative effects of economic well-being on self-esteem during adulthood as well as to examine the causal relationships. While the current study includes new factors of economic well-being, such as job satisfaction and fringe benefits, it is necessary to include additional factors, such as welfare benefits, in order to explore different effects of employment-based benefits and government support. Furthermore, the current study indicated that other socio-demographics were related to self-esteem. Although the main focus of this study identified racial and ethnic disparities in the association between economic well-being and self-esteem, we suggest that future studies may show a benefit from a deeper exploration of how other factors interact with economic well-being and self-esteem.

Little attention has been given to examining whether other aspects of economic well-being may impact self-esteem during adulthood. Given differences in levels of self-esteem and economic well-being across racial/ethnic groups, it is necessary to identify how race/ethnicity may moderate the relationship between economic well-being and self-esteem.

Little is known about how aspects of economic well-being beyond standard measures of socioeconomic status (e.g., poverty and employment), such as job satisfaction and fringe benefits, influence self-esteem; the majority of this work has focused primarily on the influence of economic well-being on self-esteem in adolescence or childhood rather than adulthood.

This study aims to explore the relationships between economic well-being (employment, poverty, fringe benefits, and job satisfaction) and self-esteem, and investigate the moderating effects of race/ethnicity on the association between economic well-being and self-esteem.

Using secondary data, ordinary linear regression analyses and logistic regression analyses were conducted.

African Americans and Hispanics were more likely to be in poverty in comparison with non-Hispanic Whites. More African Americans were unemployed than Whites. Those who received fringe benefits, were more satisfied with jobs, and those who were employed were more likely to have higher levels of self-esteem. Poverty was negatively associated with self-esteem. Interaction effects were found between African Americans and job satisfaction predicting self-esteem.

Satisfactory outcomes or feelings of happiness from the workplace may be more important to Non-Hispanic Whites, while African Americans may seek out tangible benefits rather than personal satisfaction with their jobs. Employment-based benefits are critical to increase levels of self-esteem for African Americans who have entered into labor markets and job satisfaction is more important for non-Hispanic Whites’ self-esteem in adulthood.

We suggest that future studies may show a benefit from a deeper exploration of how other factors interact with economic well-being and self-esteem, and that the use of a longitudinal data set could identify the cumulative effects of economic well-being on self-esteem during adulthood as well as the causal relationships.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychology and social

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zhou B, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Zhang XD

| 1. | Orth U, Robins RW. The development of self-esteem. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23:381-387. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB, Moffitt TE, Robins RW, Poulton R, Caspi A. Low self-esteem during adolescence predicts poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects during adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2006;42:381-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 663] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Donnellan MB, Trzesniewski KH, Robins RW, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychol Sci. 2005;16:328-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 586] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | John OP, Robins RW. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 4th ed. London, England: Guilford Press, 2021. |

| 5. | Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Freedman-Doan P, Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB. Adolescent Self-Esteem: Differences by Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Age. Self Identity. 2011;10:445-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Robins RW, Trzesniewski KH. Self-esteem development across the lifespan. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14:158-162. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Chen W, Niu G, Zhang D, Fan C, Tian Y, Zhou Z. Socioeconomic status and life satisfaction in Chinese adolescents: Analysis of self-esteem as a mediator and optimism as a moderator. Pers Individ Dif. 2016;95:105-109. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. Am Psychol. 1998;53:185-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sprecher S, Brooks JE, Avogo W. Self-esteem among young adults: Differences and similarities based on gender, race, and cohort (1990–2012). Sex Roles. 2013;69:264-275. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Twenge JM, Crocker J. Race and self-esteem: meta-analyses comparing whites, blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians and comment on Gray-Little and Hafdahl (2000). Psychol Bull. 2002;128:371-408; discussion 409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Western B, Bloome D, Sosnaud B, Tach L. Economic insecurity and social stratification. Annu Rev Sociol. 2012;38:341-359. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Thomas ME, Hughes M. The continuing significance of race: a study of race, class, and quality of life in America, 1972-1985. Am Sociol Rev. 1986;51:830-841. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Unemployment rates by age, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Bls.gov. 2022. [cited 1 October 2023]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cpsee_e16.htm. |

| 14. | Mann M, Hosman CM, Schaalma HP, de Vries NK. Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion. Health Educ Res. 2004;19:357-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 512] [Cited by in RCA: 441] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16:193-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wantchekon KA, McDermott ER, Jones SM, Satterthwaite-Freiman M, Baldeh M, Rivas-Drake D, Umaña-Taylor AJ. The Role of Ethnic-Racial Identity and Self-Esteem in Intergroup Contact Attitudes. J Youth Adolesc. 2023;52:2243-2260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Carlson C, Uppal S, Prosser EC. Ethnic differences in processes contributing to the self-esteem of early adolescent girls. J Early Adolesc. 2000;20:44-67. |

| 18. | Gray-Little B, Hafdahl AR. Factors influencing racial comparisons of self-esteem: a quantitative review. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:26-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kernis MH. Self-esteem issues and answers: A sourcebook of current perspectives. London, England: Psychology Press, 2013. |

| 20. | Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Economic hardship across the life course. Am Sociol Rev. 1999;64:548-569. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Kahn JR, Pearlin LI. Financial strain over the life course and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47:17-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kahn JR, Fazio EM. Economic status over the life course and racial disparities in health. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60 Spec No 2:76-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Berkman B. Handbook of social work in health and aging. Cary, NC: Oxford University Press, 2010. |

| 24. | Menselson T, Rehkopf DH, Kubzansky LD. Depression among Latinos in the United States: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:355-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hughes M, Kiecolt KJ, Keith VM. How racial identity moderates the impact of financial stress on mental health among African Americans. Soc Ment Health. 2014;4:38-54. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2012: Key indicators of well-being. [cited 1 October 2023]. Available from: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi?Dockey=P100FDNP.PDF. |

| 27. | Ahnquist J, Wamala SP. Economic hardships in adulthood and mental health in Sweden. The Swedish National Public Health Survey 2009. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Stam K, Sieben I, Verbakel E, de Graaf PM. Employment status and subjective well-being: the role of the social norm to work. Work Employ Soc. 2016;30:309-333. |

| 29. | Keyes CLM. Subjective well-being in mental health and human development research worldwide: An introduction. Soc Indic Res. 2006;77:1-10. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Goldsmith AH, Darity W. Social psychology, unemployment exposure and equilibrium unemployment. J Econ Psychol. 1992;13:449-471. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Goldsmith AH, Veum JR, William D. The impact of labor force history on self-esteem and its component parts, anxiety, alienation and depression. J Econ Psychol. 1996;17:183-220. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Goldsmith AH, Veum JR, Darity W. Unemployment, joblessness, psychological well-being and self-esteem: Theory and evidence. J Socio Econ. 1997;26:133-158. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kalil A, Ziol-Guest KM, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Job insecurity and change over time in health among older men and women. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65B:81-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yoshikawa H, Aber JL, Beardslee WR. The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: implications for prevention. Am Psychol. 2012;67:272-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 530] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Andersen I, Thielen K, Nygaard E, Diderichsen F. Social inequality in the prevalence of depressive disorders. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:575-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | New economics foundation. Well being in four policy area report. [cited 1 October 2023]. Available from: http://b.3cdn.net/nefoundation/ccdf9782b6d8700f7c_lcm6i2ed7.pdf. |

| 37. | Neymotin F. Linking self-esteem with the tendency to engage in financial planning. J Econ Psychol. 2010;31:996-1007. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Burgard SA, Lin KY. Bad Jobs, Bad Health? How Work and Working Conditions Contribute to Health Disparities. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Moksnes UK, Espnes GA. Self-esteem and life satisfaction in adolescents-gender and age as potential moderators. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:2921-2928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2013;139:213-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 957] [Cited by in RCA: 1055] [Article Influence: 81.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Geuskens GA, Koppes LLJ, van den Bossche SNJ, Joling CI. Enterprise restructuring and the health of employees: a cohort study: A cohort study. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54:4-9. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Stansfeld S, Candy B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health--a meta-analytic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:443-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1087] [Cited by in RCA: 998] [Article Influence: 52.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychol Rev. 1989;96:608-630. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1787] [Cited by in RCA: 1858] [Article Influence: 51.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016. |