Published online Feb 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i2.194

Peer-review started: October 8, 2023

First decision: November 30, 2023

Revised: December 2, 2023

Accepted: January 2, 2024

Article in press: January 2, 2024

Published online: February 19, 2024

Processing time: 120 Days and 22.4 Hours

Women represent the majority of patients with psychiatric diagnoses and also the largest users of psychotropic drugs. There are inevitable differences in efficacy, side effects and long-term treatment response between men and women. Psychopharmacological research needs to develop adequately powered animal and human trials aimed to consider pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of central nervous system drugs in both male and female subjects. Healthcare professionals have the responsibility to prescribe sex-specific psychopharmacotherapies with a priority to differentiate between men and women in order to minimize adverse drugs reactions, to maximize therapeutic effectiveness and to provide personalized management of care.

Core Tip: It has been largely demonstrated that women are the majority of patients with psychiatric diagnoses and also the largest users of psychotropic drugs. There are differences between men and women receiving psychotropic drugs, in terms of response, efficacy, side effects, long-term treatment outcome. There is still a lack of psychopharmacological research focusing on these differences in male and female patients. This editorial focuses on the important issue of deeply understanding the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of central nervous system drugs with a priority to differentiate between men and women in order to provide personalized management of care.

- Citation: Mazza M, De Berardis D, Marano G. Keep in mind sex differences when prescribing psychotropic drugs. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(2): 194-198

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i2/194.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i2.194

Nothwithstanding both biological research and clinical experience have largely demonstrated that pathophysiological dissimilarities between men and women significantly influence the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of psychotropic drugs, most central nervous system drugs are prescribed to women and men at the same doses[1]. Sex differences in neural and behavioral outcomes have been described in the majority of neuroimaging studies evaluating the response to antidepressants, antipsychotics, sedative-hypnotics, stimulants and mood stabilizers[2]. Sex differences exist in every major part of the brain[3], hormones and neurosteroids affect the brains of men and women differentially and dissimilar biological mechanisms may underlie sex differences in responsiveness to stress[4].

Gender psychopharmacology is a complex field of study: Not only biological and physiological differences have a pivotal importance, but also all those factors that contribute to the formation of the individual, such as psychological behaviour, social role, cultural characteristics contribute significatively. Personalized medicine could become the future, designing suitable drugs or providing more appropriate doses, with different administration intervals. Men and women use drugs and other health interventions differently, for biological reasons, as they get sick differently (for example, men seem to have higher pain tolerance and more lethal conditions, whereas women have a stronger immune response but more disabling chronic conditions) and socio-cultural reasons, as they have different attitudes toward health and care[5]. Besides, men and women respond differently to pharmacotherapies, because the drugs are absorbed and eliminated differently or because there are differences in the sensitivity and distribution of the targets on which these substances act. Gender differences in drug response are based on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variations, such as bioavailability, volume of distribution and binding to plasma proteins. There are also differences in metabolization and drug excretion: Women produce less creatinine, have a lower glomerular filtrate volume than men, and there is a tendency for women to accumulate drugs. On average, men have larger body sizes that result in larger distribution volumes and faster total clearance of most medications in men compared to women. Greater body fat in women (until older ages) may increase distribution volumes for lipophilic drugs[6].

Over the course of life, women undergo several hormonal changes connected, for example, to the onset and end of the menstrual cycle as well as pregnancy and the post-partum period. Pregnancy and lactation modify all pharmacokinetic parameters, due to changes in the volume of distribution. Besides, the placenta is a drug-metabolizing organ and the enzymes in the placenta are different from those in the liver[5].

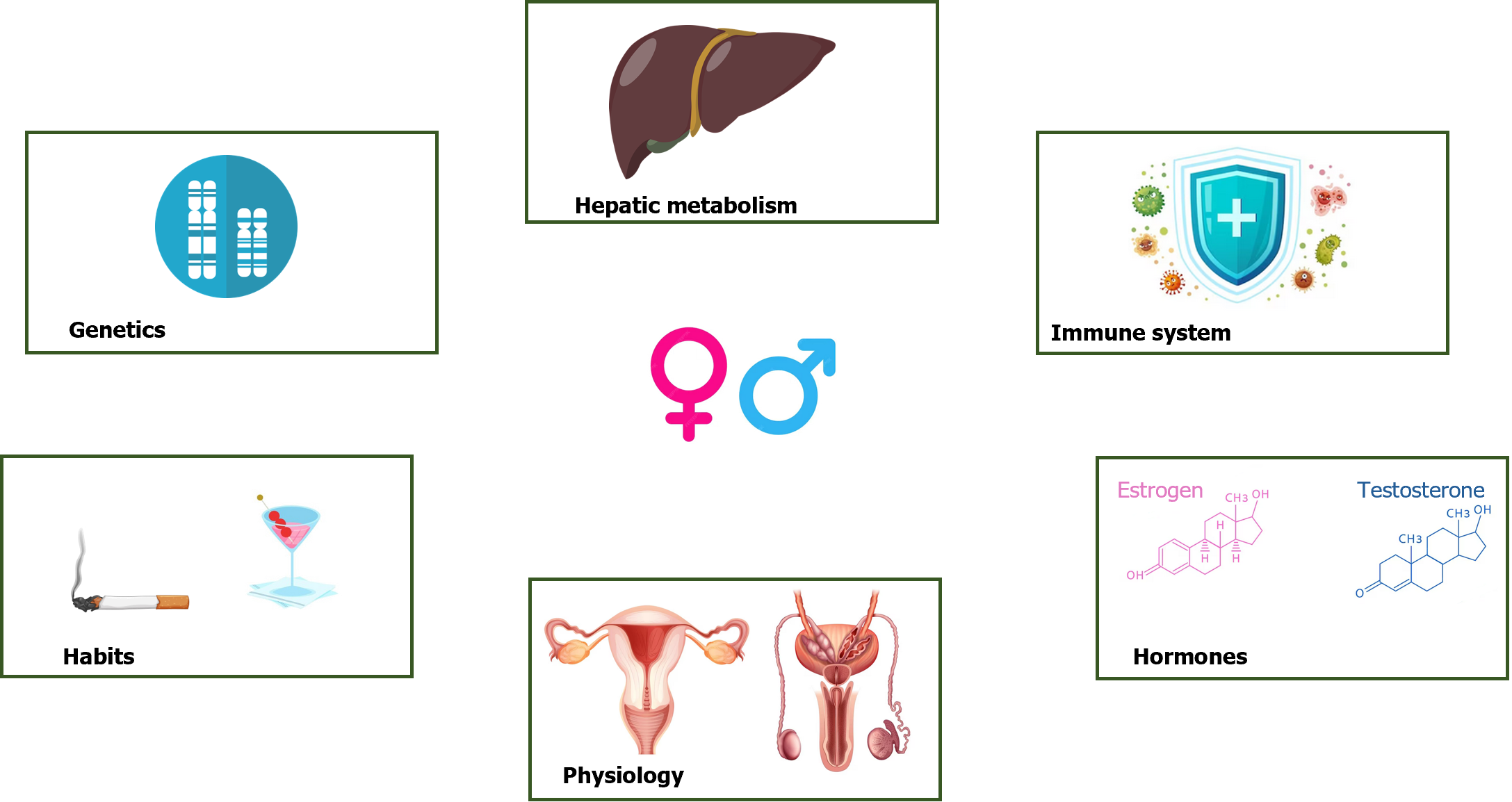

Women represent the majority of patients with psychiatric diagnoses and also the largest users of psychotropic drugs, especially antidepressants[7,8]. More women than men take multiple medications, and are more vulnerable to a number of adverse drug reactions. The reasons for this increased risk include gender-related differences in pharmacokinetic, immunological and hormonal factors (Figure 1). Among these differences, variation in levels and changes in sex steroids that subsequently interact with neurotransmitters, lower lean body mass compared to men, reduced hepatic clearance, different activity of cytochrome P450 enzymes with consequent different rates of metabolization, as well as conjugation, absorption, protein binding and renal elimination should be considered[9]. Besides, important issues regard the increased risk of QT prolongation at electrocardiogram with certain drugs compared with men even at equivalent serum concentrations and specific cutaneous reactions due to possible gender differences in T cell activation and proliferation (Figure 2). The prevalence of side effects in women is moderated by readiness to report, pain threshold, nature of the side effect, adherence to prescription, therapeutic alliance, genetic differences. It can be argued how both sex-related than gender-related factors (lifestyle factors, communication styles, health information-seeking behaviour, differences in social roles, and medication prescribing and adherence) could also lead to gender-specific differences in the occurrence, perception and reporting of adverse drug reactions. For example, women and men may perceive symptoms differently; women seem to search more actively for health information than men; there are often differences in the dose of drugs or duration of therapies prescribed to women as compared to men[10].

There is an increase of the rates of individuals reporting the use of any psychiatric medications over the last few decade, and in particular rates of antidepressant, benzodiazepine and antipsychotic use seem to be higher in females[11]. Although these data witness the advancements of medicine and the improvement of the quality of life of psychiatric patients, the other side of the coin is represented by the inevitable consideration of differences in efficacy, side effects and long-term treatment response between males and females, probably related, almost in part, to sex differences in how these drugs act on the brain and are metabolized and excreted. In addition, reproductive-aged women have repetitive variations in sex hormones with each monthly cycle that influence the onset, chronicity, and outcome of a variety of psychiatric illnesses[12].

The complexity of women’s hormonal physiology translates into mood instability related to the menstrual cycle, the manifold physiological changes of pregnancy, and, finally, the extremely complicated phase of menopause. Levels of sex hormones throughout the menstrual cycle are associated with the activation of specific hepatic enzymes and the rate of clearance of certain drugs, while the main differences between men and women in drug kinetics disappear at menopause due to the progressive decline in the production of estrogen and progesterone[7].

The specificity of psychopharmacological treatment in women arise from sex-related mechanisms of pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics up to peculiarities in terms of absorption, distribution, metabolization, and excretion. For example, in the prescription of antipsychotics, like olanzapine and clozapine, the effective dose for a woman might need to be lower than guidelines recommend for men on average (men with psychosis often require higher dosages of antipsychotic drugs related to their greater liver enzymatic clearance), while some antipsychotic side effects, weight gain for instance, are more worrisome for women than for men. After menopause, women need an increase in their antipsychotic dose, due to the decline of endogenous estrogen levels; other reproductive stages in women’s lives require special prescribing considerations as well[13-15].

Notwithstanding the number of trials enrolling women has increased following the instructions of Food and Durg Administration, women are still less represented in clinical trials because both pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a drug can be influenced by menstrual cycle phases, hormonal fluctuations, use of oral contraceptives and hormonal therapy, and life events such as pregnancy and lactation.

Clinicians should always keep in mind sex differences when prescribing psychotropic drugs and there must be adequate academic and scientific information on the potential impact of sex-related factors that affect pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics processes. This topic results critical in order to ensure drug safety and efficacy for females and males, and for informing clinical product monographs and consumer information.

There is a need of adequately powered psychopharmacological researches aimed to consider both male and female subjects in animal and human studies. In addition, clinical trials should necessarily analyze sex-related differences in results. Evaluation of the effects of sex can help to explain seemingly contradictory findings of pharmacological studies. In future researches, it could be interesting to deepen sex-specific differences in response to antidepressant therapy[16], to compare the clinical trajectory of women and men with treatment-resistent depression treated with similar augmentation strategies[17], to test different psychotropic drugs aiming to individuate which may have a greater efficacy on women than men[18] or to better evaluate sex differences in studies examining the role of the glutamate system in psychiatric disease[19]. Not only women often use drugs differently and respond to drugs differently, but they can also have unique obstacles to effective treatment (for example not being able to find child care or being prescribed treatment that has not been adequately tested on women)[20]. Although men are more likely than women to use almost all types of illicit drugs, there is evidence that women may be more susceptible to craving and relapse[21], therefore, influencing psychopharmacological treatment in terms of comorbidity and compliance with therapy. It could be useful to identify more precisely which gender-related psychosocial factors, environmental factors (chemical pollutants, cigarette smoking or oral contraceptives, nutritional variables) and psychological factors, in terms of patients’ beliefs, attitudes and expectations, that can affect the efficacy of a prescribed pharmacotherapy, and this issue results particularly applicable to centrally acting drugs.

Studying and recognizing differences between both sexes is the first step in ensuring equity and appropriateness of care. Sex is a key variable that cannot be neglected to optimize psychopharmacological treatment and to improve the efficacy and safety of drug use[22]. The development of sex-specific psychopharmacological research should aim to create a link between researchers and physicians for careful evaluation of biological, physiological, and pathological differences between men and women for the purpose of an increasing level of personalized medicine. On one hand, it is imperative to better identify the most urgent priorities and to increase awareness and knowledge about the mechanisms underlying the differences. On the other hand, it is crucial to stimulate the development of scientific and regulatory pathways that ensure that male and female populations are studied specifically and selectively.

Neuropsychopharmacology research should necessarily and primarily consider sex as a biological variable in order to reduce costs and improve benefits, reproducibility of results and rigor of methodology. Treatment guidelines should always take into account sex-related factors and their influence on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics processes as well as the occurrence of adverse drug reactions and events. Healthcare professionals have a responsability to understand the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of central nervous system drugs with a priority to differentiate between men and women in order to minimize the adeverse drugs reactions, to maximize the therapeutic effectiveness, to provide personalized management of care of patients and to contribute to the development of sex-specific psychopharmacotherapies.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Joseph MA, Oman; Seeman MV, Canada S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YX

| 1. | Romanescu M, Buda V, Lombrea A, Andor M, Ledeti I, Suciu M, Danciu C, Dehelean CA, Dehelean L. Sex-Related Differences in Pharmacological Response to CNS Drugs: A Narrative Review. J Pers Med. 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Duffy KA, Epperson CN. Evaluating the evidence for sex differences: a scoping review of human neuroimaging in psychopharmacology research. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47:430-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cahill L. Why sex matters for neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:477-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1022] [Cited by in RCA: 1023] [Article Influence: 53.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bolea-Alamanac B, Bailey SJ, Lovick TA, Scheele D, Valentino R. Female psychopharmacology matters! Towards a sex-specific psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32:125-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Crimmins EM, Shim H, Zhang YS, Kim JK. Differences between Men and Women in Mortality and the Health Dimensions of the Morbidity Process. Clin Chem. 2019;65:135-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schwartz JB. The influence of sex on pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:107-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Estancial Fernandes CS, de Azevedo RCS, Goldbaum M, Barros MBA. Psychotropic use patterns: Are there differences between men and women? PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Boyd A, Van de Velde S, Pivette M, Ten Have M, Florescu S, O'Neill S, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, Vilagut G, Haro JM, Alonso J, Kovess-Masféty V; EU-WMH investigators. Gender differences in psychotropic use across Europe: Results from a large cross-sectional, population-based study. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30:778-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rademaker M. Do women have more adverse drug reactions? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:349-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | de Vries ST, Denig P, Ekhart C, Burgers JS, Kleefstra N, Mol PGM, van Puijenbroek EP. Sex differences in adverse drug reactions reported to the National Pharmacovigilance Centre in the Netherlands: An explorative observational study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:1507-1515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Johansen ME. Psychiatric Medication Users by Age and Sex in the United States, 1999-2018. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34:732-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kornstein SG, Clayton AH. Women's Mental Health. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2023;46:xiii-xixv. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li R, Ma X, Wang G, Yang J, Wang C. Why sex differences in schizophrenia? J Transl Neurosci (Beijing). 2016;1:37-42. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Seeman MV. The Pharmacodynamics of Antipsychotic Drugs in Women and Men. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:650904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mazza M, Caroppo E, De Berardis D, Marano G, Avallone C, Kotzalidis GD, Janiri D, Moccia L, Simonetti A, Conte E, Martinotti G, Janiri L, Sani G. Psychosis in Women: Time for Personalized Treatment. J Pers Med. 2021;11:1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sramek JJ, Murphy MF, Cutler NR. Sex differences in the psychopharmacological treatment of depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016;18:447-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Moderie C, Nuñez N, Fielding A, Comai S, Gobbi G. Sex Differences in Responses to Antidepressant Augmentations in Treatment-Resistant Depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;25:479-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ma L, Xu Y, Wang G, Li R. What do we know about sex differences in depression: A review of animal models and potential mechanisms. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;89:48-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wickens MM, Bangasser DA, Briand LA. Sex Differences in Psychiatric Disease: A Focus on the Glutamate System. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | National Institute on Drug Abuse. Sex and Gender Differences in Substance Use. [cited 4 September 2023]. Available from: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/substance-use-in-women/sex-gender-differences-in-substance-use. |

| 21. | Kennedy AP, Epstein DH, Phillips KA, Preston KL. Sex differences in cocaine/heroin users: drug-use triggers and craving in daily life. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:29-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Allevato M, Bancovsky J. Psychopharmacology and women. In: RennóJ, Valadares G, Cantilino A, Mendes-Ribeiro J, Rocha R, da Silva AG. Women’s mental health: A clinical and evidence-based guide. Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2020: 227-239. |