Published online Nov 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i11.1735

Revised: October 14, 2024

Accepted: October 29, 2024

Published online: November 19, 2024

Processing time: 69 Days and 1.4 Hours

Blonanserin (BNS) is a well-tolerated and effective drug for treating schizophrenia.

To investigate which types of patients would obtain the most benefit from BNS treatment.

A total of 3306 participants were evaluated in a 12-week, prospective, multicenter, open-label post-marketing surveillance study of BNS. Brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS) scores were calculated to evaluate the effectiveness of BNS, and its safety was assessed with the incidence of adverse drug reactions. Linear regression was used to screen the influencing factors for the reduction of BPRS total score, and logistic regression was used to identify patients with a better response to BNS.

The baseline BPRS total score (48.8 ± 15.03) decreased to 27.7 ± 10.08 at 12 weeks (P < 0.001). Extrapyramidal symptoms (14.6%) were found to be the most frequent adverse drug reactions. The acute phase, baseline BPRS total score, current episode duration, number of previous episodes, dose of concomitant antipsychotics, and number of types of sedative-hypnotic agents were found to be independent factors affecting the reduction of BPRS total score after treatment initiation. Specifically, patients in the acute phase with baseline BPRS total score ≥ 45, current episode duration < 3 months, and ≤ 3 previous episodes derived greater benefit from 12-week treatment with BNS.

Patients in the acute phase with more severe symptoms, shorter current episode duration, fewer previous episodes, and a lower psychotropic drug load derived the greatest benefit from treatment with BNS.

Core Tip: This analysis included a large sample of 3306 patients with schizophrenia from the first post-marketing surveillance of blonanserin (BNS) in China. Our aim was to explore factors influencing treatment outcomes to assist in the early identification of patients with schizophrenia who are suitable for specific treatments like BNS. We found that patients in the acute phase with more severe symptoms, shorter current episode duration, and fewer previous episodes who were treated with a lower dose of concomitant antipsychotics and fewer types of sedative-hypnotic agents benefited the most from BNS treatment. These results provide valuable evidence for a more reasonable application of BNS in China.

- Citation: Xu BY, Jin K, Wu HS, Liu XJ, Wang XJ, Sang H, Li KQ, Sun MJ, Meng HQ, Deng HL, Xun ZY, Yang XD, Zhang L, Li GJ, Zhang RL, Cai DF, Liu JH, Zhao GJ, Liu LF, Wang G, Zhao CL, Guo B, Jin SC, Huang LY, Yang FD, Zheng JM, Zhan GL, Fang MS, Meng XJ, Zhang GY, Li HM, Liu XL, Li JH, Wu B, Li HY, Chen JD. Who can benefit more from its twelve-week treatment: A prospective cohort study of blonanserin for patients with schizophrenia. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(11): 1735-1745

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i11/1735.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i11.1735

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder of unknown etiologies and complex clinical presentation, with a prevalence of 1 in 300 people (0.32%), affecting approximately 24 million people worldwide[1]. Its onset is typically in late adolescence or early adulthood, and it significantly impairs social function, imposing a heavy burden on families and society. Although many studies have been carried out on its treatment, the outcomes of best-practice treatment are often unsatisfactory[1]. A meta-analysis of 50 research results revealed that the median proportion of schizophrenia patients who met clinical recovery criteria was only 13.5%[2]. The development of antipsychotic drugs with different mechanisms to improve the efficacy of schizophrenia treatment is still ongoing. A person-centered regimen is recommended as a crucial foundation of treatment optimization by various guidelines[3-5]. Moreover, early identification of schizophrenia patients more likely to benefit from treatment with different antipsychotics is of great significance for symptom control, shortened disease course, and patient compliance.

Blonanserin (BNS) is a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with unique pharmacological properties. As a complete antagonist, BNS occupies both dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A (5-HT2A) receptors, and it can also fully bind to brain dopamine D3 receptors in patients with schizophrenia[6]. BNS has been widely used in Japan, Korea, and China for the treatment of schizophrenia. Its efficacy and safety in treating schizophrenia have been demonstrated by randomized double-blind controlled trials[7-12], a prospective study[13], and a meta-analysis[14]. However, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials has revealed that BNS poses a higher risk of akathisia, agitation/excitement, and extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) than a combination of risperidone and paliperidone[15]. A larger sample study is necessary to further investigate the safety of BNS for patients with schizophrenia.

Although interim or subgroup analyses using data from post-marketing surveillance (PMS) studies have been reported that demonstrate the effectiveness and safety of BNS in real-world settings[16,17], neither of these analyses included the whole set of patients in the PMS, nor did they investigate the characteristics of Chinese patients that benefited from BNS treatment. To identify patients more likely to benefit from BNS treatment, in this study we screened predictive factors for brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS) total score reduction on a total of 3306 patients with schizophrenia from 32 clinical institutions across mainland China.

This 12 weeks, prospective, non-interference, observational PMS study was conducted in mainland China. BNS-treated schizophrenia patients from 32 clinical institutions, diagnosed and staged by investigators, were screened from September 2018 to June 2022. Inclusion criteria included the diagnosis of schizophrenia with International Classification of Diseases 10th Edition and BNS treatment. This study was approved by the ethics committees of the leading site, The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (ethics approval number: 2018-093), and the other sites. All patients enrolled were required to provide written informed consent.

Enrolled patients took BNS in accordance with the approved dosage and administration method: Orally twice a day after meals. Typically, the treatment started with a 4 mg dose per intake, which was gradually increased. The dosage should be adjusted on the basis of the patient’s condition with the aim of maintaining a daily dose of 8-16 mg and a maximum of 24 mg per day. In this study, comprehensive effectiveness analysis was based on the full analysis set, and safety analysis was based on the safety set.

Similarly to a previous study[18], adverse drug reactions (ADRs) during the treatment period were reported and coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities developed by the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use[19]. The reported ADRs were reviewed by independent professionals to minimize inter-clinician heterogeneity and guarantee inter-rater reliability.

Disease severity was measured by BPRS[20,21], a clinician-rated scale widely used to evaluate the presence and severity of various psychiatric symptoms. BPRS has been extensively studied and been demonstrated to be a valid and reliable instrument for most patients with psychiatric symptoms, especially those with schizophrenia[22]. In this study, five subscales underlying the 18-items BPRS were defined as follows: (1) Anxiety/depression: Anxiety, guilt, depression, and somatic concern; (2) Anergia: Emotional withdrawal, motor retardation, blunted affect, and disorientation; (3) Thought disturbance: Conceptual disorganization, grandiosity, hallucination, and unusual thought content; (4) Activation: Tension, mannerisms and posturing, and excitement; and (5) Hostility/suspiciousness: Hostility, suspiciousness, and uncooperativeness. The five-factor model scores were collected at baseline, 2-4, 6-8, and 12 weeks. Better response was defined as reduction of BPRS total score ≥ 50%[23].

Statistical analysis was conducted using R 4.2.0. For continuous variables, the number of subjects (n), mean, and standard deviation were presented. For categorical variables, frequency and percentage were presented. Independent sample t-tests were used to compare continuous variables between groups, and χ2-tests were used for categorical variables. The pairwise t-test was used to compare continuous variables before and after treatment. Linear regression analysis was conducted to analyze the relationship between baseline variables and the reduction of the BPRS total score at the final visit, in which doses of other antipsychotic drugs were converted to chlorpromazine equivalents[24]. A mixed model for repeated measurements was used to assess the BPRS total score over time. Baseline variables were treated as fixed effects, and patients were treated as random effects, all nested within visits. The Akaike information criterion was used to screen variables. The least square means of BPRS scores at different visits were estimated and used to produce plots. Logistic regression was used to identify patients with a better response to BNS. Better response or not (reduction of BPRS total score ≥ 50% or not) was treated as a dependent variable, and factors that influence the BPRS score reduction were treated as independent variables. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to evaluate the model, and the area under curve value was calculated. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 3306 patients were included in both the full analysis set and the safety set. According to the baseline demo

| Variates | mean ± SD |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 1342 (40.6) |

| Age (years) | 34.5 ± 14.18 |

| Height (cm) | 165.6 ± 7.66 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.5 ± 12.44 |

| Duration of illness (month) | 89.1 ± 111.09 |

| Baseline BPRS total score | 48.8 ± 15.03 |

| Baseline BPRS factor scores | |

| Anxiety/depression | 9.8 ± 4.11 |

| Anergia | 10.2 ± 3.69 |

| Thought disturbance | 12.1 ± 4.30 |

| Activation | 6.7 ± 3.26 |

| Hostility/suspiciousness | 10.0 ± 3.89 |

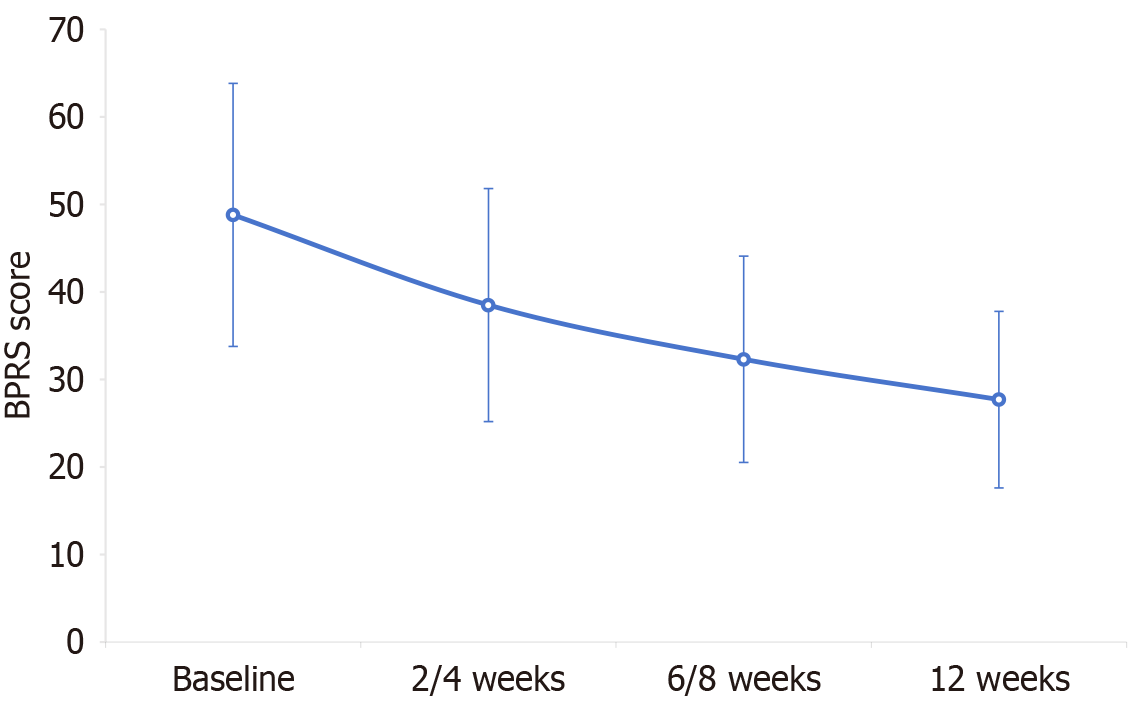

The effectiveness analysis of BNS revealed that the BPRS total score for the schizophrenic patients decreased gradually with increasing duration of BNS treatment (Figure 1). There were statistically significant differences between the BPRS total score before and after treatment at each visit (all P < 2.2 e-16 compared with the baseline). After 2-4 weeks of treatment, the five-factor model scores of the patients were also significantly lower than the baseline scores (P < 0.001) and thereafter exhibited a continuous downward trend (6-8 weeks and 12 weeks; Table 2).

| BPRS | Baseline (n = 3306) | 2-4 weeks (n = 3188) | 6-8 weeks (n = 2957) | 12 weeks (n = 2775) | F value | P value |

| Total score | 48.8 ± 15.03 | 38.5 ± 13.32 | 32.3 ± 11.78 | 27.7 ± 10.08 | 1574 | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety/depression | 9.8 ± 4.11 | 8.2 ± 3.46 | 7.1 ± 3.07 | 6.2 ± 2.67 | 638.5 | < 0.001 |

| Anergia | 10.2 ± 3.69 | 8.4 ± 3.14 | 7.2 ± 2.74 | 6.3 ± 2.38 | 898.3 | < 0.001 |

| Thought disturbance | 12.1 ± 4.30 | 9.4 ± 3.80 | 7.6 ± 3.33 | 6.4 ± 2.85 | 1410 | < 0.001 |

| Activation | 6.7 ± 3.26 | 5.3 ± 2.61 | 4.5 ± 2.17 | 4.0 ± 1.74 | 695.5 | < 0.001 |

| Hostility/suspiciousness | 10.0 ± 3.89 | 7.3 ± 3.17 | 5.8 ± 2.63 | 4.8 ± 2.16 | 1700 | < 0.001 |

Among the 3306 patients included, 622 (18.9%) patients developed ADRs, with 656 mild ADRs in 443 (13.4%) patients, 219 moderate ADRs in 164 (5.0%) patients, and 16 severe ADRs in 15 (0.5%) patients. Among the 3306 patients, 486 (14.6%) patients exhibited ADRs of EPS and 240 (7.2%) patients exhibited ADRs of akathisia. Weight gain occurred in 39 (1.2%) patients and blood prolactin increased in 33 (1.0%) patients (Table 3). All ADRs were manageable.

| ADRs | Mild patients, n (%) | Mild cases | Moderate patients, n (%) | Moderate cases | Severe patients, n (%) | Severe cases |

| Total ADRs | 443 (13.4) | 656 | 164 (5.0) | 219 | 15 (0.5) | 16 |

| Neurological disorders | 352 (10.6) | 420 | 127 (3.8) | 159 | 7 (0.2) | 8 |

| Akathisia | 170 (5.1) | 174 | 66 (2.0) | 68 | 4 (0.1) | 4 |

| Tremor | 97 (2.9) | 100 | 27 (0.8) | 27 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Dystonia | 54 (1.6) | 54 | 23 (0.7) | 24 | 2 (0.1) | 2 |

| Parkinsonism | 43 (1.3) | 44 | 22 (0.7) | 22 | 1 (0.0) | 1 |

| Investigations | 74 (2.2) | 85 | 23 (0.7) | 25 | 3 (0.1) | 3 |

| Elevated transaminase level | 6 (0.2) | 6 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Weight gain | 34 (1.0) | 34 | 5 (0.2) | 5 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Increased blood prolactin | 20 (0.6) | 20 | 12 (0.4) | 12 | 1 (0.0) | 1 |

| Increased blood glucose | 2 (0.1) | 2 | 1 (0.0) | 1 | 1 (0.0) | 1 |

| Decreased white blood cell count | 2 (0.1) | 2 | 1 (0.0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Prolonged electrocardiogram QT | 2 (0.1) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 | 1 (0.0) | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 48 (1.5) | 50 | 11 (0.3) | 11 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Eye disorders | 8 (0.2) | 10 | 1 (0.0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 16 (0.5) | 18 | 4 (0.1) | 5 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Kidney and urinary disorders | 2 (0.1) | 2 | 4 (0.1) | 4 | 1 (0.0) | 1 |

Univariate analysis was conducted on patients with BPRS reduction regarding patient-specific factors and treatment factors. It was found that sex, age, height, weight, disease phase, current episode duration, baseline BPRS total score, baseline BPRS factor scores, number of previous episodes, whether or not other antipsychotics were concomitantly used, mean daily dose of concomitant antipsychotics, whether or not sedative-hypnotic agents were concomitantly used, and number of types of sedative-hypnotic agents were associated with a change in BPRS score (Supplementary Table 1). Linear regression analysis found that six independent variables, namely acute phase (β = 5.42; P < 0.001), baseline BPRS total score (β = 0.51; P < 0.001), current episode duration (β = -0.03; P < 0.001), number of previous episodes (β = -0.22; P = 0.024), mean daily dose of concomitant antipsychotics (β = -0.01; P < 0.001), and number of types of sedative-hypnotic agents (β = -1.22; P = 0.002), were significantly associated with a reduced BPRS score (Table 4). We also investigated the factors related to the final-visit BPRS reduction in non-acute-phase patients with prominent negative symptoms (defined as item score of blunted affect ≥ 4)[25] at baseline through multivariate analysis. The results showed that number of previous episode (β = -0.38; P = 0.003), daily dose of other antipsychotics (β = -0.01; P = 0.011), baseline BPRS score (β = 0.34; P < 0.001), and number of types of sedative-hypnotic agents (β = -2.53; P = 0.003) were all statistically associated with final-visit BPRS reduction in these patients. We also found that baseline blunted affect score ≥ 4 was associated with a greater reduction of BPRS in these patients (Table 5).

| Characteristic | β | 95%CI | P value |

| Current episode duration (month) | -0.03 | -0.05 to -0.01 | < 0.001 |

| Whether in acute phase | |||

| No | 0.00 | N/A | N/A |

| Yes | 5.42 | 4.0 to 6.9 | < 0.001 |

| Previous episodes | -0.22 | -0.41 to -0.03 | 0.024 |

| Baseline BPRS score | 0.51 | 0.47 to 0.56 | < 0.001 |

| Mean daily dose of concomitant anti-psychiatrics1 | -0.01 | -0.01 to 0.00 | < 0.001 |

| Number of types of sedative-hypnotic agents | -1.22 | -2.00 to -0.44 | 0.002 |

| Characteristic | β | 95%CI | P value |

| Baseline blunted affect score | N/A | N/A | 0.061 |

| ≤ 3 | 0.00 | N/A | N/A |

| ≥ 4 | 2.45 | -0.12 to 5.01 | N/A |

| Disease duration (months) | -0.02 | -0.04 to 0.01 | 0.217 |

| Previous onset | -0.38 | -0.63 to -0.13 | 0.003 |

| Mean daily dose of concomitant anti-psychiatrics1 | -0.01 | -0.01 to 0.00 | 0.011 |

| Baseline BPRS score | 0.34 | 0.27 to 0.41 | < 0.001 |

| Number of types of sedative-hypnotic agents | -2.53 | -4.17 to -0.90 | 0.003 |

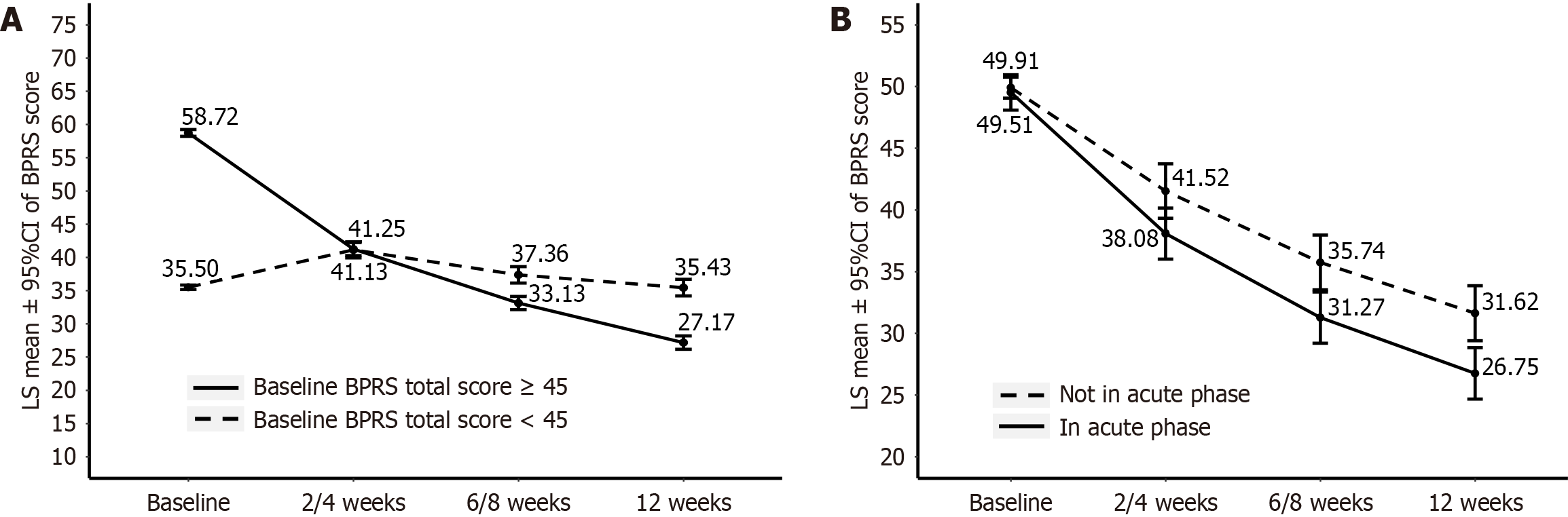

Logistic regression was used to identify the patients that would benefit more from BNS treatment. The change in BPRS total score from baseline to 12 weeks was taken as the dependent variable, with the four above-mentioned patient-specific factors serving as independent variables. Four logistic regression models were fitted (Supplementary Tables 2-5). Based on the model results, ROC analysis was conducted to determine the optimal cutoff value (Supplementary Figure 1). The ROC analysis revealed that patients in the acute phase with baseline BPRS total score ≥ 45, current episode duration < 3 months, and no more than three previous episodes would derive greater benefit from the 12-week treatment with BNS (Supplementary Figure 2). The BPRS scores of patients with baseline BPRS score ≥ 45 exhibited a continuous downward trend over time, whereas those of patients with baseline BPRS score < 45 tended to increase in the early stage, then decrease from 2-4 weeks, with the decrease smaller than that of patients with baseline BPRS score ≥ 45 (Figure 2A). The BPRS scores of patients in the acute phase decreased monotonically with increasing treatment time, and the decrease was greater than that of non-acute-phase patients at each visit (Figure 2B). The BPRS scores of patients with current episode duration < 3 months also decreased monotonically, with a greater decrease than that of patients with current episode duration ≥ 3 months at each visit (Supplementary Figure 3A). In addition, the BPRS scores of patients with no more than three previous episodes exhibited a continuous downward trend, with a more rapid decrease in the early stages (2-4 weeks) than that of the other patients (Supplementary Figure 3B).

This study found that six independent variables, namely acute phase, baseline BPRS total score, current episode duration, number of previous episodes, dose of concomitant antipsychotics, and number of types of sedative-hypnotic agents, were significantly associated with the reduction of BPRS total score after 12-week treatment. Similar associations were observed in non-acute-phase patients with prominent baseline negative symptoms. Baseline blunted affect score ≥ 4 was also associated with a greater reduction of BPRS in these patients. We also demonstrated that BNS was beneficial for schizophrenia patients, with significant improvement of symptoms. Furthermore, the BPRS score gradually decreased with the continuation of BNS treatment. In terms of safety, most ADRs were mild, with only 0.5% classified as severe. The most common ADRs were neurological disorders, such as akathisia, tremor, and dystonia, and the incidence of EPS in this study was likely lower than that in the Chinese population receiving 8-24 mg BNS for up to 10 weeks in a phase 3 clinical trial (48.46%)[26]. We also verified the results of an interim analysis on BNS that reported its safety and effectiveness in treating schizophrenia in mainland China[16].

As a part of person-centered medication, the early identification of patients suitable for BNS treatment is of great significance for symptom control, functioning recovery, patient compliance, and relapse prevention. Using a linear mixed-effects model, we found that six independent variables - acute phase, baseline BPRS score, current episode duration, number of previous episodes, dose of concomitant antipsychotics, and number of types of sedative-hypnotic agents - were significantly associated with the reduction of BPRS score after 12-week treatment.

BNS could be more likely to have a significant effect (i.e., reduction of BPRS total score ≥ 50%) in patients in the acute phase. Patients with acute schizophrenia have significantly impaired social function and are at greater risk of violent attacks, suicide, and self-injury than during stable periods, leading to increased hospitalization rates and a higher social burden. Deciding the best method for treating acute schizophrenia remains a major challenge in clinical practice, as hospitalization time significantly depends on the treatment regimen[27]. Since the acute phase of schizophrenia is characterized by prominent positive symptoms[28,29], the significant reduction of BPRS total score after 12-week treatment for patients in the acute phase could be attributed to the strong affinity of BNS to the D2 receptor. This result is consistent with the significant decrease in the scores for the hostility/suspiciousness and thought disturbance factors of BPRS in this study. Previous randomized controlled trials also demonstrated that BNS significantly alleviated positive symptoms in patients with acute schizophrenia[11,26].

In addition, a patient with BPRS total score ≥ 45 at baseline could also be more likely to experience a larger reduction of BPRS total score of ≥ 50% after 12 weeks treatment than a patient having a BPRS total score < 45 at baseline. This suggests that patients with moderate or more severe symptoms could benefit more from the intervention, as a schizophrenia patient with a BPRS total score of 41 is considered to be ‘moderately ill’[30]. Since schizophrenia manifests complex presentations, such as dysfunctions in cognition, behavior, and emotions, this larger reduction may be related to the potent D2, D3, and 5-HT2A receptor affinity of BNS[11]. Previous studies have revealed that D2 receptors are associated with the improvement of positive symptoms and that D3 and 5-HT2A receptors are associated with the mitigation of negative and affective symptoms[31]. D3 antagonists may also improve cognitive and social function[31]. Both the positive and negative subscores of the positive and negative syndrome scale in previous clinical trials[11,26] and the BPRS five-factor model scores in this study were significantly improved upon treatment with BNS, demonstrating that it can reduce multidimensional symptoms.

BNS could also be more likely to have a significant effect in the early stages of schizophrenia than in later stages. Duration of the current episode of less than 3 months and no more than three previous episodes are two factors attributed to a larger reduction of BPRS total score after treatment. These factors suggest that untreated psychosis patients with a shorter duration of this condition have better treatment outcomes, consistent with a previous study[32], emphasizing the high importance of the early identification of schizophrenia patients more likely to benefit from BNS treatment. In addition, a previous study showed that patients with a full initial response to treatment continuing for at least the first 3 years are at lower risk of relapse[33].

It has been argued that sedative-hypnotic agents and a higher dose of antipsychotics mediate the improved early response in patients; however, these two factors were negatively correlated with BPRS total score reduction at 12 weeks in our data. We postulate that this negative correlation could partially be due to differences in the patient population included in our study, which was originally designed to investigate the safety and use of BNS in a real-world clinical setting, with only a few inclusion criteria employed. Schizophrenia is a chronic disease, although the severity and frequency of relapse of psychiatric symptoms vary, with some negative symptoms and cognitive deficits related to schizophrenia becoming more persistent over time and typically persisting even after the acute phase of mental illness subsides, causing poor prognosis and limited functioning[29,34,35]. It is difficult to treat patients who still have negative symptoms even in the non-acute phase of schizophrenia. Antipsychotic polypharmacy is often given to these patients, and they are prone to side effects due to overdose in real-world practice[36]. As a result, the patient’s condition deteriorates due to oversedation or severe EPS[37]. Therefore, we paid special attention to patients who were in the non-acute phase and had prominent baseline negative symptoms (baseline blunted affect score ≥ 4)[25]. As expected, a stronger negative correlation between number of types of sedative-hypnotic agents and BPRS reduction was found in this population (β: -2.53 vs -1.22; Tables 4 and 5). We also found that patients with more prominent baseline negative symptoms tended to show greater BPRS reduction after treatment with BNS, which can be partially attributed to its affinity to D3 and 5-HT2A receptors. However, the result was not statistically significant, possibly due to the limited number of negative symptom items in BPRS.

The strengths of this study are as follows. First, it further validated the safety and effectiveness of BNS in treating schizophrenia in mainland China through a large-scale PMS study. Second, it identified the clinical characteristics of schizophrenia patients who would benefit the most from BNS, providing evidence for its treatment of schizophrenia and a theoretical basis for its effective application in clinical practice. Third, this study found a trend of improved residual symptoms upon BNS treatment, especially in patients with prominent negative symptoms, which should be validated in future studies. However, several limitations of the study should be noted. As a non-interference study in the real world, some confounding factors cannot be removed, and a causal analysis cannot be conducted. Results of the current analysis, including the independent variables associated with greater reduction of BPRS score, need further investigation through strictly designed trials. Moreover, the study lacked control groups. The efficacy of BNS and other atypical antipsychotic drugs in acute-phase treatment requires further research.

The results of this study indicate that BNS is both safe and efficacious for treating patients with schizophrenia. Impor

The authors are grateful to all the patients and their families, physicians, and paramedics who participated in this trial for their valued contribution. This study is supported by Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd. and Sumitomo Pharma (Suzhou) Co., Ltd.

| 1. | Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Diminic S, Stockings E, Scott JG, McGrath JJ, Whiteford HA. Global Epidemiology and Burden of Schizophrenia: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:1195-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 859] [Cited by in RCA: 957] [Article Influence: 136.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jääskeläinen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, McGrath JJ, Saha S, Isohanni M, Veijola J, Miettunen J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:1296-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 711] [Cited by in RCA: 619] [Article Influence: 51.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthøj B, Gattaz WF, Thibaut F, Möller HJ; WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia - a short version for primary care. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2017;21:82-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, Benjamin S, Lyness JM, Mojtabai R, Servis M, Walaszek A, Buckley P, Lenzenweger MF, Young AS, Degenhardt A, Hong SH; (Systematic Review). The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:868-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 80.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhao JP, Zheng YJ, Zhang HY, Si TM, Shi SX, Su L, Ouyang X, Liu ZN, Huang JZ, Wang CY, Lu Z, Wu RR, Wang JJ, Ma XH, Yang FD, Cui Y. [Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Schizophrenia (2nd Edition)]. Beijing: Chinese Medical Multimedia Press, 2015. |

| 6. | Sakayori T, Tateno A, Arakawa R, Kim WC, Okubo Y. Evaluation of dopamine D3 receptor occupancy by blonanserin using [11C]-(+)-PHNO in schizophrenia patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2021;238:1343-1350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Garcia E, Robert M, Peris F, Nakamura H, Sato N, Terazawa Y. The efficacy and safety of blonanserin compared with haloperidol in acute-phase schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:615-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kishi T, Matsuda Y, Iwata N. Cardiometabolic risks of blonanserin and perospirone in the management of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Takaki M, Okahisa Y, Kodama M, Mizuki Y, Sakamoto S, Ujike H, Uchitomi Y. Efficacy and tolerability of blonanserin in 48 patients with intractable schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2012;24:380-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Harvey PD, Nakamura H, Murasaki M. Blonanserin versus haloperidol in Japanese patients with schizophrenia: A phase 3, 8-week, double-blind, multicenter, randomized controlled study. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2019;39:173-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Harvey PD, Nakamura H, Miura S. Blonanserin vs risperidone in Japanese patients with schizophrenia: A post hoc analysis of a phase 3, 8-week, multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled study. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2020;40:63-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yang J, Bahk WM, Cho HS, Jeon YW, Jon DI, Jung HY, Kim CH, Kim HC, Kim YK, Kim YH, Kwon JS, Lee SY, Lee SH, Yi JS, Yoon BH, Kim SH. Efficacy and tolerability of Blonanserin in the patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, risperidone-compared trial. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33:169-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Woo YS, Park JE, Kim DH, Sohn I, Hwang TY, Park YM, Jon DI, Jeong JH, Bahk WM. Blonanserin Augmentation of Atypical Antipsychotics in Patients with Schizophrenia-Who Benefits from Blonanserin Augmentation?: An Open-Label, Prospective, Multicenter Study. Psychiatry Investig. 2016;13:458-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kishi T, Matsuda Y, Nakamura H, Iwata N. Blonanserin for schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized, controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:149-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kishi T, Matsui Y, Matsuda Y, Katsuki A, Hori H, Yanagimoto H, Sanada K, Morita K, Yoshimura R, Shoji Y, Hagi K, Iwata N. Efficacy, Tolerability, and Safety of Blonanserin in Schizophrenia: An Updated and Extended Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2019;52:52-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wu H, Wang X, Liu X, Sang H, Bo Q, Yang X, Xun Z, Li K, Zhang R, Sun M, Cai D, Deng H, Zhao G, Li J, Liu X, Zhan G, Chen J. Safety and Effectiveness of Blonanserin in Chinese Patients with Schizophrenia: An Interim Analysis of a 12-Week Open-Label Prospective Multi-Center Post-marketing Surveillance. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:935769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bo Q, Wang X, Liu X, Sang H, Xun Z, Zhang R, Yang X, Deng H, Li K, Chen J, Sun M, Zhao G, Liu X, Cai D, Zhan G, Li J, Li H, Wang G. Effectiveness and safety of blonanserin in young and middle-aged female patients with schizophrenia: data from a post-marketing surveillance. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Saito T, Sugimoto S, Sakaguchi R, Nakamura H, Ishigooka J. Efficacy and Safety of Blonanserin Oral Tablet in Adolescents with Schizophrenia: A 6-Week, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2022;32:12-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brown EG, Wood L, Wood S. The medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA). Drug Saf. 1999;20:109-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 681] [Cited by in RCA: 827] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Silverstein ML, Mavrolefteros G, Close D. BPRS syndrome scales during the course of an episode of psychiatric illness. J Clin Psychol. 1997;53:455-458. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Chan DW, Lai B. Assessing psychopathology in Chinese psychiatric patients in Hong Kong using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yee A, Ng BS, Hashim HMH, Danaee M, Loh HH. Cultural adaptation and validity of the Malay version of the brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS-M) among patients with schizophrenia in a psychiatric clinic. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Leucht S, Busch R, Kissling W, Kane JM. Early prediction of antipsychotic nonresponse among patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:352-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Norwegian Institute of Public Health. ATC/DDD Index 2024. [cited 15 June 2024]. Available from: https://atcddd.fhi.no/atc_ddd_index/. |

| 25. | Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT Jr, Kane JM, Lasser RA, Marder SR, Weinberger DR. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:441-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1537] [Cited by in RCA: 1658] [Article Influence: 82.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Li H, Yao C, Shi J, Yang F, Qi S, Wang L, Zhang H, Li J, Wang C, Wang C, Liu C, Li L, Wang Q, Li K, Luo X, Gu N. Comparative study of the efficacy and safety between blonanserin and risperidone for the treatment of schizophrenia in Chinese patients: A double-blind, parallel-group multicenter randomized trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;69:102-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Masters GA, Baldessarini RJ, Öngür D, Centorrino F. Factors associated with length of psychiatric hospitalization. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:681-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Addington J, Addington D. Positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Their course and relationship over time. Schizophr Res. 1991;5:51-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sabe M, Zhao N, Crippa A, Kaiser S. Antipsychotics for negative and positive symptoms of schizophrenia: dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled acute phase trials. NPJ Schizophr. 2021;7:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Leucht S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Hamann J, Etschel E, Engel R. Clinical implications of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:366-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 683] [Cited by in RCA: 679] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Stahl SM. Stahl’ s Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications. 5th ed. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2021. |

| 32. | Penttilä M, Jääskeläinen E, Hirvonen N, Isohanni M, Miettunen J. Duration of untreated psychosis as predictor of long-term outcome in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 570] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hui CLM, Honer WG, Lee EHM, Chang WC, Chan SKW, Chen ESM, Pang EPF, Lui SSY, Chung DWS, Yeung WS, Ng RMK, Lo WTL, Jones PB, Sham P, Chen EYH. Long-term effects of discontinuation from antipsychotic maintenance following first-episode schizophrenia and related disorders: a 10 year follow-up of a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:432-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Huxley P, Krayer A, Poole R, Prendergast L, Aryal S, Warner R. Schizophrenia outcomes in the 21st century: A systematic review. Brain Behav. 2021;11:e02172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Vita A, Barlati S. Recovery from schizophrenia: is it possible? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31:246-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lähteenvuo M, Tiihonen J. Antipsychotic Polypharmacy for the Management of Schizophrenia: Evidence and Recommendations. Drugs. 2021;81:1273-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Carbon M, Correll CU. Thinking and acting beyond the positive: the role of the cognitive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2014;19 Suppl 1:38-52; quiz 35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |