Published online Nov 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i11.1718

Revised: August 30, 2024

Accepted: September 5, 2024

Published online: November 19, 2024

Processing time: 98 Days and 0.3 Hours

Improvements in the standard of living have led to increased attention to perianal disease. Although surgical treatments are effective, the outcomes of post-operative recovery (POR) are influenced by various factors, including individual differences among patients, the characteristics of the disease itself, and the psychological state of the patient. Understanding these factors can help healthcare providers develop more personalized and effective post-operative care plans for patients with perianal disease.

To investigate the effect of illness perception (IP) and negative emotions on POR outcomes in patients with perianal disease.

A total of 146 patients with perianal disease admitted to the First People's Hospital of Changde City from March to December 2023 were recruited. We employed a general information questionnaire, the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). We used the 15-item Quality of Recovery Score (QoR-15) to measure patients’ recovery effects. Finally, we conducted Pearson’s correlation analysis to examine the relationship between pre-operative IP and anxiety and depression levels with POR quality.

Fifty-three (36.3%) had poor knowledge of their disease. Thirty (20.5%) were suspected of having anxiety and 99 (67.8%) exhibited symptoms. Forty (27.4%) were suspected of having depression and 102 (69.9%) displayed symptoms. The B-IPQ, HADS-A, HADS-D, and QoR-15 scores were 46.82 ± 9.97, 12.99 ± 3.60, 12.58 ± 3.36, and 96.77 ± 9.85, respectively. There was a negative correlation between pre-operative IP, anxiety, and depression with POR quality. The influence of age and disease course on post-operative rehabilitation effect are both negative. The impact of B-IPQ, HADS-A, and HADS-D on POR was negative. Collectively, these variables accounted for 72.6% of the variance in POR.

The quality of POR in patients with perianal disease is medium and is related to age, disease course, IP, anxiety, and depression.

Core Tip: We found a significant negative correlation linking pre-operative illness perception (IP), anxiety, depression, and post-operative recovery in patients with perianal disease. We identified age, disease duration, IP, anxiety, and depression as key factors that negatively impact recovery, highlighting the importance of psychological support and timely medical interventions.

- Citation: Hou SX, Dai FJ, Wang XX, Wang SW, Tian T. Correlation linking illness perception, negative emotions, and the post-operative recovery effect in patients with perianal disease. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(11): 1718-1727

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i11/1718.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i11.1718

Perianal disease is a major ailment afflicting patients; common forms include hemorrhoids, anal fissures, perianal abscesses, and anal fistulas[1]. Perianal disease is prevalent across all age groups in China and significantly affects patients’ daily lives and work efficiency. Medical treatment often provides short-term symptom relief but does not fundamentally solve the problem. Surgery is an effective treatment for most patients with colorectal disease. For example, compared to conservative treatment, surgical excision can significantly shorten the time needed for symptom relief from an average of 24 days to 3.9 days[2]. Additionally, the recurrence rate after surgical treatment is much lower than that after conservative treatment, with one-year recurrence rates of 6.4% and 25.4%, respectively[3]. For patients with anal fistulas, the cure rate with surgical treatment is very high, usually exceeding 90%[4]. However, the post-operative recovery (POR) effects are influenced by numerous factors, including individual differences in patients, the characteristics of the illness itself, and the psychological state of the patients.

Disease knowledge/awareness, also known as illness perception (IP), refers to the extent of a patient’s understanding of his/her condition and encompasses the nature of the disease, its course, treatment methods, and prognosis. Patients’ perceptions and experiences of their disease can influence their self-regulatory behaviors, which in turn determine actions such as seeking medical attention, adherence to treatment, and psychological state[5-7]. In their study on patients with diabetes, Kim et al[5] showed a correlation between IP and coping behaviors (e.g., medication adherence and diet). These direct or indirect factors can influence the prognosis and outcome of the disease and significantly affect patient recovery. Rajpura and Nayak[6], in their research on older adult patients with hypertension, found that IP has a better predictive role of treatment compliance than factors related to the use of medication and associated risks. Additionally, negative emotions such as anxiety and depression, significantly impact patient recovery. Prolonged negative emotions not only affect the patient’s mental health but may also influence wound healing and immune function through physiological mechanisms, thereby affecting POR outcomes[8].

Research on the treatment outcomes of patients with perianal disease continues to emerge; however, most studies focus on specific drugs, treatment methods, or anesthesia techniques[9,10]. There is relatively limited research on the factors influencing POR quality in patients with perianal disease, and further exploration in this area is needed. However, there is a lack of relevant literature on IP among patients with perianal disease. Hence, we aimed to gain a deeper under

We conducted a survey study. We selected patients with perianal disease who were admitted to The First People’s Hospital of Changde City between March and December 2023.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients aged ≥ 18 years who are undergoing surgery for perianal abscess for the first time; (2) Those who voluntarily agreed to participate in this study after fully understanding its objectives and procedures; (3) Individuals with the necessary education level to cooperate and complete the research process smoothly; and (4) Those who had no psychological intervention before their operation.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Hospitalization for non-surgical treatment, emergency admission, other significant organic diseases of important organs, severe illness, or pregnancy or breastfeeding; (2) A history of infectious diseases, mental disorders, or previous use of anti-anxiety or anti-depressant medications; and (3) Discharge within 3 days of hospitalization, or false or incomplete information on the questionnaire.

The sample size calculation method used in this study for multivariable correlation research is based on the formula proposed by the Chinese scholar Ni Ping: N = (UαS/δ)².

With α = 0.05, then Uα = 1.96. We conducted a preliminary investigation of the POR levels in 20 patients with perianal diseases, with a standard deviation of S = 8.91. To maximize the sample size, we used 0.25 times the standard deviation S to set the permissible error δ, which is calculated as 8.91 × 0.25 = 2.23. Using the formula, this yields N approximately 62. Considering a 20% loss and invalid response rate, the actual required sample size is 75.

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we enrolled 146 patients, meeting the sample size requirement.

In the colorectal ward, patients who met the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate in the study were screened. Subsequently, through thorough communication with the patients, we explained in detail the objectives, significance, and procedures of the study and informed the patients that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. Finally, the patients signed an informed consent form.

During the survey process, we held one-on-one interviews to ensure patients could think independently and respond as much as possible when completing the questionnaires. The day before the surgery, we provided patients with a series of assessment tools, including the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ)[11] and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)[12], to evaluate their IP and psychological state. On the second day after surgery, we administered the 15-item Quality of Recovery (QoR-15)[13] to assess the patient’s quality of recovery.

We utilized several assessment tools to gather comprehensive data from the patients:

The general information questionnaire: This tool collects basic demographic and clinical data from patients’ medical records, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), family income, caregiving arrangements, type of disease, disease duration, and underlying conditions.

B-IPQ[11]: The B-IPQ consists of 9 items, each scored from 0 to 10. The first eight items are summed up to give a total score for the scale, with a maximum of 80 points (the last item is open-ended). Higher scores denote a poorer under

HADS[12]: The HADS includes two subscales, one for anxiety (HADS-A) and one for depression (HADS-D), which are used to screen for symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients in general hospitals. Each subscale contains seven questions rated on a scale of 0 to 3 according to the severity of the symptoms. The total score for each subscale ranges from 0 to 21; 0-7 implies no symptoms, 8-10 suggests possible symptoms, and 11-21 indicates definite symptoms of anxiety or depression.

QoR-15[13]: The QoR-15 is designed to measure POR quality in patients who underwent surgery, with two versions (forms A and B) comprising 15 items that cover physical health (physical comfort, pain, and physical independence) and mental health (emotional support and emotions). In Form A, each item is scored from 0 to 10, where 0 means that the issue is not present or is very mild, and 10 suggests that the problem is constantly present or highly impactful. Form B uses a reverse-scoring system. The total QoR-15 score ranges from 0 to 150, with higher scores implying better recovery quality.

(1) Pre-operative IP and anxiety and depression levels in patients with perianal disease; (2) POR in patients with perianal disease; (3) The correlation linking pre-operative IP, anxiety, depression, and POR quality in patients with perianal disease; and (4) Other potential factors influencing POR include patient age, sex, and baseline health conditions.

After importing the data from Excel into SPSS, we checked and compared the data to ensure their integrity and correctness and then analyzed the data. We performed descriptive statistical analyses on general data. We expressed the measurement data using the mean ± SD, and the counting data as a percentage. T-test was used to compare the POR quality scores between the two groups, while one-way analysis of variance was used for the comparison among the three groups. We analyzed the relationships among pre-operative IP, anxiety, depression, and POR quality in patients with perianal disease using Pearson’s correlation analysis. We used multiple regression analysis to identify the factors influencing early POR quality.

Among the 146 patients, the incidence was higher in males, and 72.6% of patients were married. In terms of disease duration, 36.9% of patients suffered from it for < 6 months; the shortest duration was 10 days; 43.1% suffered from it for > 12 months, and the longest duration was > 15 years. Among these, hemorrhoids and rectal mucosal prolapse were the most common forms of perianal disease (Table 1).

| Variables | n (%) |

| Age (years) | |

| ≤ 44 | 60 (41.1) |

| 45-59 | 57 (39.0) |

| ≥ 60 | 29 (19.9) |

| Sex | 0 |

| Male | 83 (56.8) |

| Female | 63 (43.2) |

| Average monthly household income (10000 yuan) | |

| < 0.5 | 83 (56.9) |

| 0.5-1.0 | 44 (30.1) |

| 1.1-1.5 | 13 (8.9) |

| 1.5 | 6 (4.1) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 106 (72.6) |

| Single | 40 (27.4) |

| Underlying disease | |

| Yes | 56 (38.4) |

| No | 90 (61.6) |

| Education level | |

| Junior high school and below | 50 (34.2) |

| High school or technical secondary school | 56 (38.4) |

| College or above | 40 (27.4) |

| Caregiver | |

| Spouse | 84 (57.5) |

| Immediate family | 31 (21.2) |

| Other | 23 (15.8) |

| No | 8 (5.5) |

| Diseases type | |

| Hemorrhoids | 54 (37.0) |

| Rectocele | 36 (24.7) |

| Anal fistula | 18 (12.3) |

| Perianal abscess | 20 (13.7) |

| Other | 18 (12.3) |

| Disease duration (months) | |

| < 6 | 54 (37.0) |

| 6-12 | 29 (19.9) |

| > 12 | 63 (43.1) |

Among the 146 patients with perianal disease, 53 (36.3%) had poor disease knowledge/awareness, 91 (62.3%) had moderate disease/knowledge awareness, and two (1.4%) had good disease/knowledge awareness. Thirty patients (20.5%) had suspected symptoms of anxiety, whereas 99 (67.8%) displayed definite symptoms. Forty patients (27.4%) showed suspected symptoms of depression, and 102 (69.9%) exhibited definite symptoms. The scores for B-IPO, HADS-A, and HADS-D were 46.82 ± 9.97, 12.99 ± 3.60, and 12.58 ± 3.36, respectively. See Table 2 for details.

| Scales | Items | Total score range | Average score |

| B-IPQ | 8 | 0-80 | 46.82 ± 9.97 |

| HADS-A | 7 | 0-21 | 12.99 ± 3.60 |

| HADS-D | 7 | 0-21 | 12.58 ± 3.36 |

The average QoR-15 score of 146 patients with perianal disease was (96.77 ± 9.85), and the average scores were the following: (1) Physical comfort: 36.28 ± 5.90; (2) Physical independence: 11.27 ± 2.04; (3) Mental support: 14.98 ± 2.61; (4) Pain: 8.49 ± 3.07; and (5) Emotion: 25.76 ± 8.01

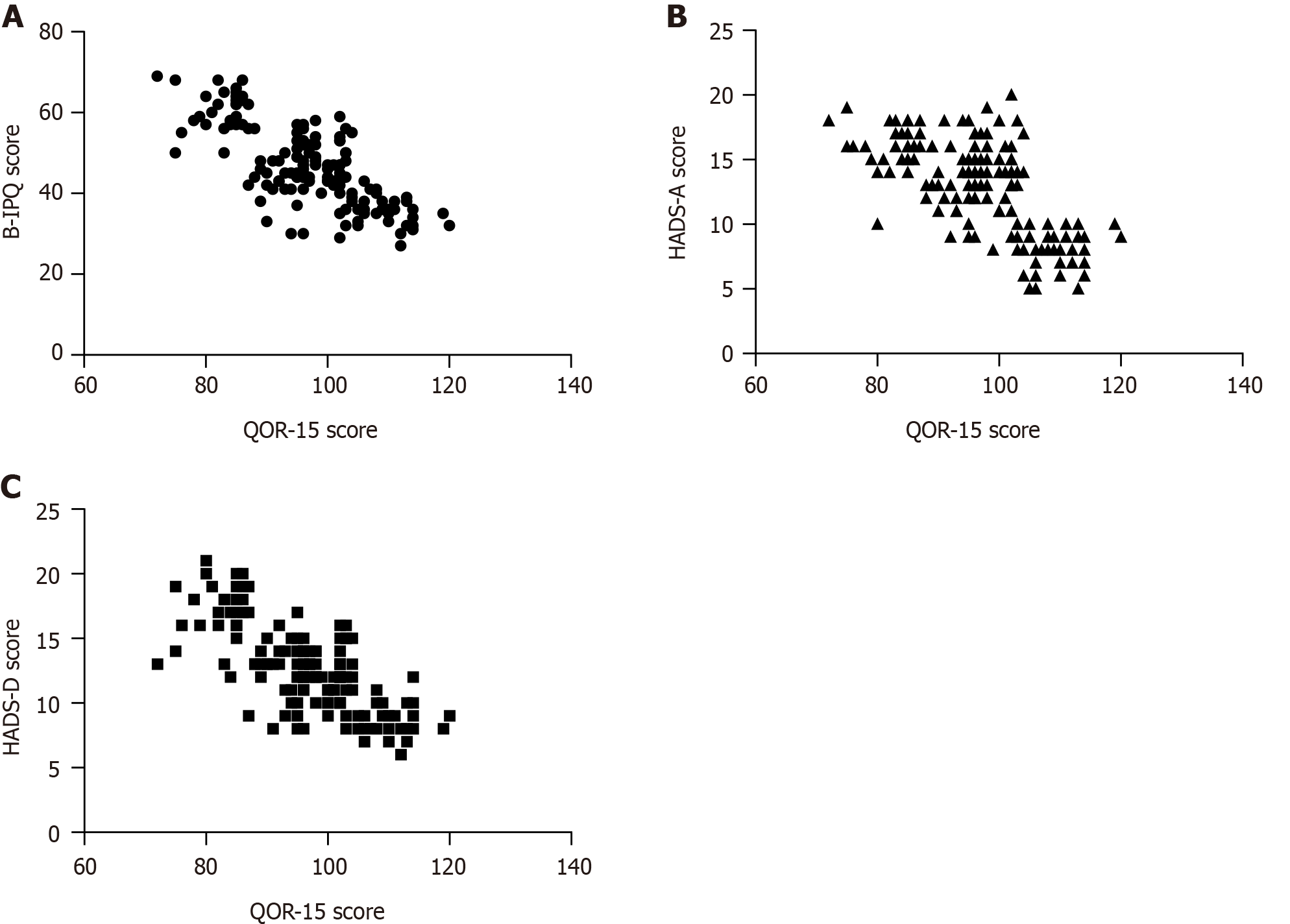

Pre-operative IP, anxiety, and depression were negatively correlated with POR in patients with perianal disease (r =

There were differences in the QoR-15 scores among patients of different ages, average monthly family income, and disease course (P < 0.05). See Table 4 for details.

| Variables | n | QoR-15 score | F/t | P value |

| Age (years) | 19.324 | < 0.001 | ||

| ≤ 44 | 60 | 102.18 ± 8.04 | ||

| 45-59 | 57 | 92.74 ± 10.16 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 29 | 93.52 ± 7.28 | ||

| Sex | 0.047 | 0.963 | ||

| Male | 83 | 96.81 ± 10.80 | ||

| Female | 63 | 96.73 ± 8.52 | ||

| Average monthly household income (10000 yuan) | 5.496 | 0.001 | ||

| < 0.5 | 83 | 95.69 ± 10.01 | ||

| 0.5-1.0 | 44 | 95.36 ± 8.98 | ||

| 1.1-1.5 | 13 | 103.62 ± 8.34 | ||

| > 1.5 | 6 | 107.33 ± 4.08 | ||

| Marital status | 0.113 | 0.910 | ||

| Married | 106 | 96.72 ± 9.76 | ||

| Single/divorced/separated | 40 | 96.93 ± 10.21 | ||

| Underlying disease | 1.223 | 0.223 | ||

| Yes | 56 | 98.04 ± 8.34 | ||

| No | 90 | 95.99 ± 10.65 | ||

| Education level | 0.104 | 0.901 | ||

| Junior high school and below | 50 | 96.30 ± 8.72 | ||

| High school or technical secondary school | 56 | 97.18 ± 10.43 | ||

| College or above | 40 | 96.80 ± 10.54 | ||

| Caregiver | 0.853 | 0.467 | ||

| Spouse | 84 | 96.20 ± 9.82 | ||

| Immediate family | 31 | 98.45 ± 9.82 | ||

| Other | 23 | 97.87 ± 9.69 | ||

| No | 8 | 93.13 ± 11.04 | ||

| Disease type | 0.511 | 0.728 | ||

| Hemorrhoids | 54 | 97.61 ± 10.17 | ||

| Rectocele | 36 | 97.00 ± 9.27 | ||

| Anal fistula | 18 | 95.94 ± 10.58 | ||

| Perianal abscess | 20 | 94.15 ± 10.67 | ||

| Other | 18 | 97.56 ± 8.77 | ||

| Disease duration (months) | 11 | 97.09 ± 7.75 | ||

| < 6 | 54 | 101.54 ± 9.96 | 11.516 | < 0.001 |

| 6-12 | 29 | 94.38 ± 6.41 | ||

| > 12 | 63 | 93.79 ± 9.59 |

In the regression analysis based on the QoR-15 score, the regression equation was significant with F = 64.208, P < 0.001. The effect of age (β = -1.490, P = 0.016), and disease duration (β = -1.998, P < 0.001) on POR outcomes is negative. B-IPQ (β = -0.604, P < 0.01), HADS-A (β = -0.331, P < 0.001), and HADS-D (β = -0.944, P < 0.001) negatively affected POR. Together, these variables explained 72.3% of the variance in POR. See Table 5 for details.

| Variables | B | β | t value | P value |

| Age (years) | -1.49 | -0.114 | -2.433 | 0.016 |

| Disease duration (months) | -1.998 | -0.182 | -3.897 | < 0.001 |

| Average monthly household income (10000 yuan) | -0.010 | -0.001 | -0.018 | 0.985 |

| B-IPQ | -0.331 | -0.335 | -4.946 | < 0.001 |

| HADS-A | -0.604 | -0.221 | -3.825 | < 0.001 |

| HADS-D | -0.944 | -0.321 | -5.247 | < 0.001 |

| Constant | 138.796 | - | 50.179 | < 0.001 |

Based on the results of the multiple linear regression, the model formula is: Y = 138.796 - 1.490 × age - 1.998 × disease duration - 0.010 × monthly household income - 0.331 × B-IPQ score - 0.604 × HADS-A score - 0.944 × HADS-D score.

We selected 20 patients from our hospital for external validation of the model between January and April 2024. The results showed that the multiple linear regression model predicted the POR of patients with perianal diseases with a sensitivity of 83.33% (10/12), specificity of 75.00% (6/8), and accuracy of 80.00% (16/20).

With rapid developments in the medical field and a deeper understanding of patient needs, assessment methods for POR quality are constantly evolving and improving[14]. Traditional assessment indicators, such as mortality rate, complication rate, and length of hospital stay, which reflect surgical outcomes and patient recovery, are no longer able to fully represent patients’ actual recovery status due to improvements in surgical safety and hospital efficiency[15]. Thus, patient-centered POR assessment methods have emerged that focus more on patients’ individual experiences and quality of life[16].

A meta-analysis showed that the QoR-15 is a valid, reliable, and responsive patient-centered outcome measure for surgical patients. The QoR-15 has demonstrated excellent discriminative validity, with a split-half reliability of 0.80 (95% confidence interval [95%CI]: 0.75-0.84), and a test-retest reliability of 0.97 (95%CI: 0.95-0.98); it is highly acceptable to both patients and clinicians[17]. We used the QoR-15 to assess the quality of POR of patients with perianal disease. The overall recovery quality of these patients was at a moderate level, with a total score of 96.77 ± 9.85 points. This is lower than the QoR-15 scores reported by Lorenzen et al[18] of patients who underwent surgery for degenerative lumbar spine disease (108.1 ± 19.2 points). This discrepancy may be due to the significant differences in the pathophysiology and surgical intervention between perianal disease and degenerative lumbar spine disease. Degenerative lumbar spine disease may involve more complex surgical procedures and longer operative times, and the corresponding post-operative management and rehabilitation support may need to be more comprehensive. In a study by Djafarrian et al[19], patients’ overall quality of life was only moderate at ten days after anorectal surgery. This finding differs from the higher evaluation of recovery quality on the second post-operative day in the present study. This discrepancy may be due to early POR quality being influenced by surgical outcome, anesthetic effects, and immediate complications, whereas assessments at later post-operative time points may be more affected by complications, chronic pain, and psychological adaptation. Additionally, the difference may stem from the varying timing and tools used for evaluation in the two studies.

In addition, most patients with perianal disease had a moderate level of IP and experienced negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression, before surgery. This is consistent with previous studies’ findings[20,21]. We also found that pre-operative IP and anxiety and depression levels were negatively correlated with POR quality in patients with perianal disease. IP refers to the formal and informal information that patients acquire to form their views on the disease. A moderate level of pre-operative IP implies that patients have some understanding of the upcoming surgery and its potential consequences. However, there may still be uncertainty and concerns, which can lead to feelings of anxiety and depression in patients; if negative emotions are not managed properly, they may affect POR outcomes. Furthermore, pre-operative IP, anxiety, and depression levels influenced POR outcomes, which is consistent with the results of Matiwos et al[22]. Anxiety and depression not only affect patients’ mental well-being but may also affect their physiological functions, such as sleep patterns, pain perception, and immune system function[20]. Physiological changes may reduce patient tolerance to surgery and post-operative treatment, increase the risk of post-operative complications, and con

In this study, we explored the impact of age on POR outcomes in patients with perianal diseases. The results indicated a significant negative correlation between age and POR outcomes, with older adult patients showing a marked negative effect (β = -1.490, P = 0.016). This suggests that older adult patient population may face more challenges during the POR process. Specifically, for each additional year, the expected change in recovery outcomes shows a declining trend. This may be attributed to the weakened immune system in older adults, which affects their ability to resist infections, thereby delaying the POR process. This finding highlights the need for healthcare professionals to pay special attention to the specific needs of older adult patients when formulating POR plans, as they potentially require more personalized and enhanced rehabilitation support.

Our study also showed that the course of disease is one factor affecting the quality of early POR, which is in line with the conclusion of prior studies[23]. The data showed that the longer the disease course, the lower the quality of early POR. This may be due to the long course of the patient’s disease, gradual deterioration in the patient’s physical condition, or increased difficulty of the operation, resulting in greater tissue damage, which also affects the patient’s tolerance toward the operation and healing of the post-operative wound.

Based on the results of multiple linear regression analysis, we included age, disease duration, B-IPQ, HADS-A, and HADS-D as predictor variables to construct a multiple linear regression model. The model has a sensitivity of 83.33% and a specificity of 75.00%, indicating that the model has high efficacy in predicting POR outcomes. We have built this predictive model to assist healthcare professionals in identifying patients who may face challenges in recovery and to provide more personalized interventions for them. Although the model shows good predictive accuracy in the current sample, its practicality and feasibility in clinical practice still need to be assessed through implementation research.

Although this study provides valuable insights into the POR of patients with perianal diseases, our sample may not represent the entire patient population, especially given the specific sociodemographic characteristics and disease features of the participants. Future research should address this limitation on sample bias by including a larger and more diverse sample to yield more reliable results. In addition, in conducting an observational study, we could not capture the complete trajectory of recovery or the effects that changed over time. Due to its observational nature, our study may not have established causal relationships between the variables. Future research should consider psychosocial factors, such as social support networks, cultural beliefs, or personal resilience. In the future, we plan to investigate long-term outcomes, including chronic pain management, return to work or daily activities, and overall quality of life.

Overall, the quality of early POR of hospitalized patients with perianal disease was moderate, with associated factors including age, disease duration, IP, anxiety, and depression. Consequently, in the clinical management of patients with perianal disease, the healthcare team should offer customized pre-operative education, psychological interventions, POR plans, and social support to facilitate physical recovery and enhance the quality of POR.

| 1. | Faber MT, Frederiksen K, Palefsky JM, Kjaer SK. Risk of Anal Cancer Following Benign Anal Disease and Anal Cancer Precursor Lesions: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29:185-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cohee MW, Hurff A, Gazewood JD. Benign Anorectal Conditions: Evaluation and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101:24-33. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Davis BR, Lee-Kong SA, Migaly J, Feingold DL, Steele SR. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:284-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Owen HA, Buchanan GN, Schizas A, Cohen R, Williams AB. Quality of life with anal fistula. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2016;98:334-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim H, Sereika SM, Lingler JH, Albert SM, Bender CM. Illness Perceptions, Self-efficacy, and Self-reported Medication Adherence in Persons Aged 50 and Older With Type 2 Diabetes. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2021;36:312-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rajpura J, Nayak R. Medication adherence in a sample of elderly suffering from hypertension: evaluating the influence of illness perceptions, treatment beliefs, and illness burden. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20:58-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shiyanbola OO, Unni E, Huang YM, Lanier C. Using the extended self-regulatory model to characterise diabetes medication adherence: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e022803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Clark SM, Pocivavsek A, Nicholson JD, Notarangelo FM, Langenberg P, McMahon RP, Kleinman JE, Hyde TM, Stiller J, Postolache TT, Schwarcz R, Tonelli LH. Reduced kynurenine pathway metabolism and cytokine expression in the prefrontal cortex of depressed individuals. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016;41:386-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Durgun C, Tüzün A. The use of a loose seton as a definitive surgical treatment for anorectal abscesses and complex anal fistulas. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2023;32:1149-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hwang SH. Trends in Treatment for Hemorrhoids, Fistula, and Anal Fissure: Go Along the Current Trends. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2022;6:150-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Moss-morris R, Horne R. The illness perception questionnaire: A new method for assessing the cognitive representation of illness. Psychol Health. 1996;11:431-445. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 941] [Cited by in RCA: 963] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28548] [Cited by in RCA: 31806] [Article Influence: 757.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Stark PA, Myles PS, Burke JA. Development and psychometric evaluation of a postoperative quality of recovery score: the QoR-15. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:1332-1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 603] [Article Influence: 50.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Neville A, Lee L, Antonescu I, Mayo NE, Vassiliou MC, Fried GM, Feldman LS. Systematic review of outcomes used to evaluate enhanced recovery after surgery. Br J Surg. 2014;101:159-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Myles PS. More than just morbidity and mortality - quality of recovery and long-term functional recovery after surgery. Anaesthesia. 2020;75 Suppl 1:e143-e150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Menear M, Gagnon A, Rivet S, Gabet M. [Quality indicators of person-centred and recovery-oriented care for mental health issues]. Sante Ment Que. 2023;48:29-65. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Myles PS, Shulman MA, Reilly J, Kasza J, Romero L. Measurement of quality of recovery after surgery using the 15-item quality of recovery scale: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128:1029-1039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lorenzen MD, Pedersen CF, Carreon LY, Clemensen J, Andersen MO. Measuring quality of recovery (QoR-15) after degenerative spinal surgery: A prospective observational study. Brain Spine. 2024;4:102767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Djafarrian R, Hübner M, Vuagniaux A, Duvoisin C, Martin D, Demartines N, Hahnloser D. Recovery to Usual Activity After Outpatient Anorectal Surgery. World J Surg. 2020;44:1985-1993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cioli VM, Gagliardi G, Pescatori M. Psychological stress in patients with anal fistula. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1123-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang G, Wu Y, Cao Y, Zhou R, Tao K, Wang L. Psychological states could affect postsurgical pain after hemorrhoidectomy: A prospective cohort study. Front Surg. 2022;9:1024237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Matiwos B, Tesfaw G, Belete A, Angaw DA, Shumet S. Quality of life and associated factors among women with obstetric fistula in Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21:321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhou Y, Peng M, Zhou J. Quality of life in children undergoing tonsillectomy: a cross-sectional survey. Ital J Pediatr. 2023;49:52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |