Published online Nov 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i11.1708

Revised: September 23, 2024

Accepted: October 24, 2024

Published online: November 19, 2024

Processing time: 72 Days and 23.4 Hours

The mental well-being of individuals with coronary heart disease (CHD) during the intensive care unit (ICU) transition period is a multifaceted and significant concern. In this phase, the individuals might encounter psychological challenges like anxiety and depression, which can impede their recuperation and potentially have lasting effects on their health.

To investigate the correlation among psychological factors in CHD patients in the ICU transition period.

A questionnaire survey was conducted with 119 patients admitted to the ICU after coronary artery bypass grafting between March and December 2023. Varia

The total scores for anxiety, depression, fear of disease progression, and social support were (7.50 ± 1.41) points, (8.38 ± 1.62) points, (35.19 ± 8.14) points, and (36.34 ± 7.08) points, respectively (P < 0.05). Multivariate regression analysis showed that both the level of disease progression and social support affected the level of postoperative depression and anxiety in patients.

The anxiety and depression levels were positively related to each dimension of phobia disease progression and negatively related to each dimension of social support among patients with CHD.

Core Tip: Patients with coronary heart disease may experience negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression, which affect disease progression. This study found a correlation between anxiety and depression, fear of disease progression, and social support level and confirmed it through a multiple linear regression model. By probing the factors that affect patients’ negative emotions, this study provides a reference for medical staff to formulate reasonable intervention measures.

- Citation: Xu Y, Ma HX, Liu SS, Gong Q. Correlation among anxiety and depression, fear of disease progression, and social support in coronary heart disease. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(11): 1708-1717

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i11/1708.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i11.1708

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a common ischemic heart disease caused mainly by coronary artery insufficiency or stenosis. The clinical manifestations include chest pain and tightness and, in severe cases, myocardial infarction can occur[1]. Coronary artery bypass grafting is a common treatment for CHD and can improve myocardial blood supply, angina pectoris, and cardiac function[2]. Fear of progression refers to the fear-in individuals facing diseases-of the biological, psychological, and social consequences of the disease or reactive and conscious disease recurrence[3]. Related studies have confirmed that the functional response caused by moderate fear of disease is beneficial to the patient’s health by,

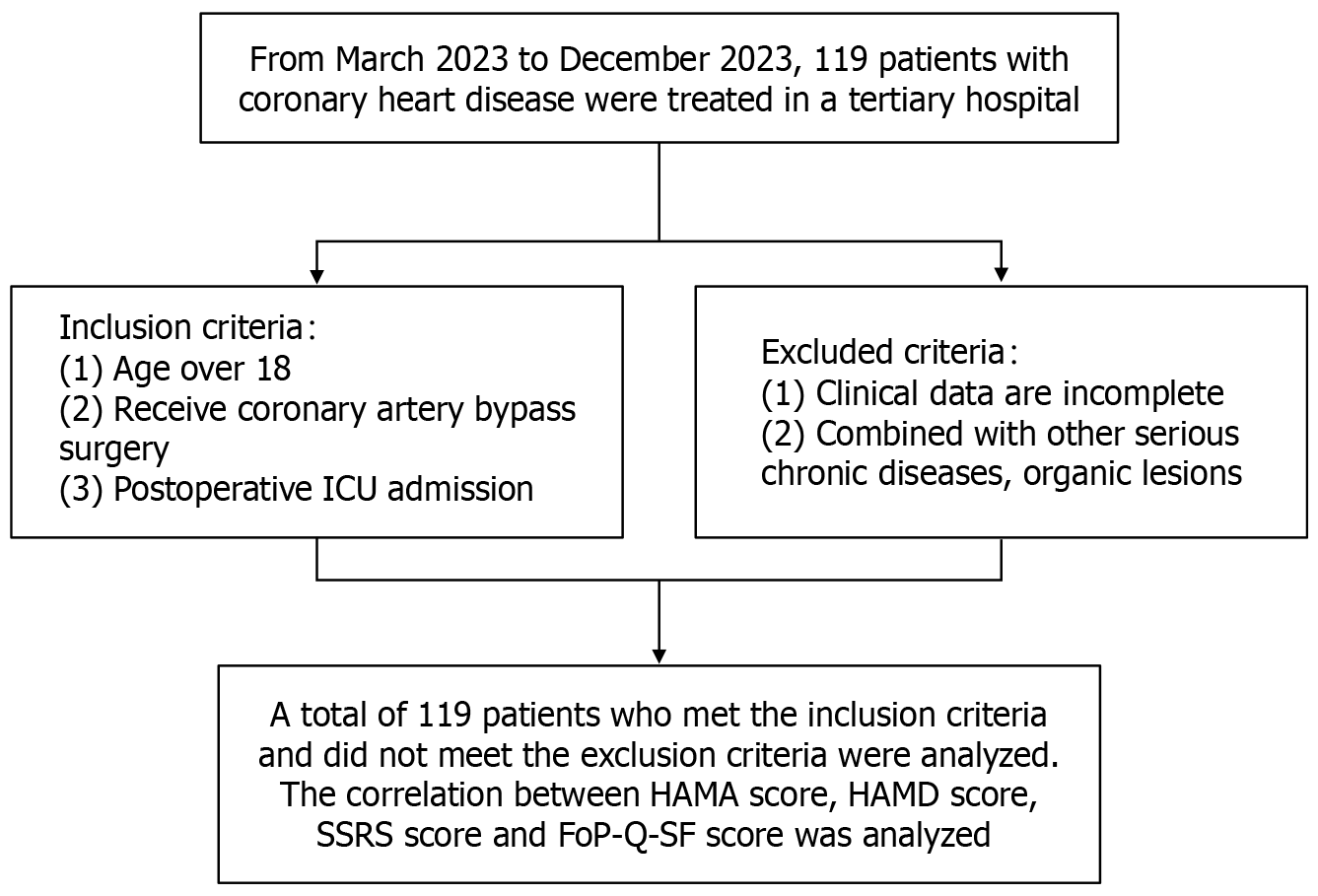

In this observational study, a questionnaire survey was conducted with 119 patients admitted to the Cardiovascular Surgery Intensive Care Unit after coronary artery bypass grafting between March 2023 and December 2023. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age 18 years and above; (2) In line with the World Health Organization or the International Society of Cardiology to develop diagnostic criteria for CHD; and (3) Patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting in our hospital and were admitted to the ICU for cardiac and vascular surgery after the operation. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Incomplete clinical data; and (2) Patient experiencing other serious chronic or organic diseases. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (Figure 1).

Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) and Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) scores. We used the HAMA[6] and HAMD scores[7] to assess the patients’ degree of anxiety and depression. The HAMA score includes 14 items. If the total score was less than 7 points, it indicated that there was no anxiety state; the more serious the anxiety state, the higher the HAMA score. The HAMD score comprises 17 items. If the total score was less than 8 points, it indicated that there was no depression. Similar to the HAMA score, the severity of depression was positively correlated with the HAMD score; that is, the more severe the depression, the higher the HAMD score. Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form (Fop-Q-SF)[8]. The scale involves two aspects: Physical health and social family with 12 items, “never” scoring 1 point, “always” scoring 5 points, with a scoring range of 12-60 points. The score was positively correlated with the patient’s fear, of which 40 points and below indicated that the fear was low and 41 points and above indicated a high level of fear. Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS)[9]. We used the SSRS to appraise the social support of individuals, including three aspects - objective, subjective, and utilization-for all 10 items. The score range is 12-66 points, with a high score indicating better support. A score of 22 was low support, 23-44 was medium, and 45-66 was high.

Two participants entered all the data. The logical errors in the data included in the study were further verified to enhance the dependability of the data.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0. Quantitative data conforming to a normal distribution were described by mean ± SD, and the t-test was used for difference analysis. Qualitative data were described as frequency or percentage (%), and the rate between the two groups was compared using two tests. The correlations between the HAMA, HAMD, FoP-Q-SF, and SSRS scores were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation analysis. All statistical tests were two-sided, and the test level was α = 0.05.

This study included 119 participants (92 males and 27 females). The age distribution spanned 44 to 79 years, with 43 individuals aged 60 years or younger and 76 individuals aged over 60 years. Regarding the duration of the condition, 47 patients had a course of 5 years or less, while 72 patients had a course exceeding 5 years. Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

| Cases (n = 119) | Percentage | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 92 | 77.31% |

| Female | 27 | 22.69% |

| Age (year) | ||

| ≤ 60 | 43 | 36.13% |

| > 60 | 76 | 63.87% |

| Course (year) | ||

| ≤ 5 | 47 | 39.50% |

| > 5 | 72 | 60.50% |

| Residential location | ||

| City | 45 | 37.82% |

| Villages or towns | 74 | 62.18% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 96 | 80.67% |

| Unmatched | 23 | 19.33% |

| Educational background | ||

| Primary and below | 52 | 43.70% |

| Junior high school | 29 | 24.37% |

| High school or technical secondary school | 21 | 17.64% |

| Junior college or above | 17 | 14.29% |

| Occupation | ||

| Be on the job | 27 | 22.69% |

| Self-employed people or farmer | 58 | 48.73% |

| Take leave or retire | 17 | 14.29% |

| Unemployed | 17 | 14.29% |

| Type of medical insurance | ||

| Worker with medical insurance | 45 | 37.82% |

| Medical insurance for residents | 74 | 62.18% |

| Smoking | ||

| Yes | 37 | 31.09% |

| No | 82 | 68.91% |

| Drinking | ||

| Yes | 34 | 28.57% |

| No | 85 | 71.43% |

| Monthly household income (RMB) | ||

| < 6000 | 74 | 62.19% |

| 6000-9000 | 34 | 28.57% |

| > 9000 | 11 | 9.24% |

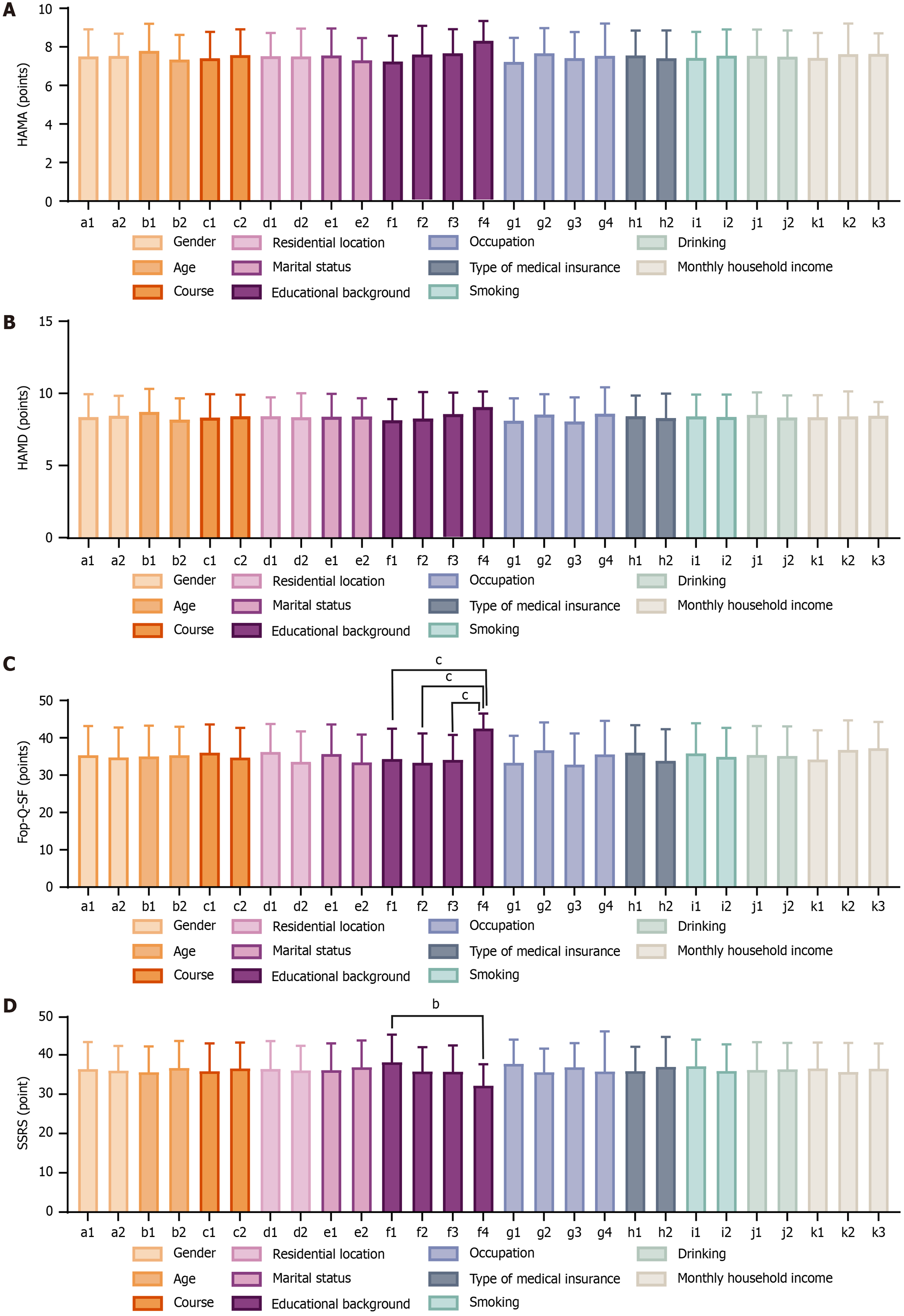

The mean anxiety score of the patients was 7.50 ± 1.41. A total of 88 patients exhibited symptoms of anxiety, as indicated by a HAMD score of 7 or higher. Statistically significant variations in anxiety scores were not observed across different demographic and clinical factors (P > 0.05). These findings are detailed in Figure 2A.

In this analysis, the mean depression score for the patients was 8.38, with a standard deviation of 1.62. A total of 87 patients were identified as suffering from depression, defined by a HAMD score greater than or equal to 8 points. Significant differences in depression scores were not observed among the patients (P > 0.05). These findings are shown in Figure 2B.

In this study, the mean fear of disease progression score for patients was 35.19 ± 8.14 points. This score was derived from the FoP-Q-SF, with 83 patients exhibiting a low fear of disease progression (scores ≤ 40 points) and 36 patients showing a high fear of disease progression (scores > 40 points). Notably, significant variations in the fear of disease progression scores were identified across patients of different educational backgrounds (P < 0.05). A visual representation of these findings is shown in Figure 2C.

In this investigation, the mean social support score for patients was 36.34 ± 7.08. The result was categorized into low, moderate, and high levels of social support, with 5 patients identifying with low support (SSRS ≤ 22), 98 with moderate support (23 ≤ SSRS ≤ 45), and 16 with high support (SSRS > 45). Significant differences in social support levels were observed among patients with varying educational backgrounds (P < 0.05). These findings are graphically depicted in Figure 2D.

With regard to the correlation between anxiety and depression, fear, and support, the results showed that high anxiety and depression can lead to high fear, demonstrating a positive correlation. High social support stabilizes the patient’s negative emotions, demonstrating a negative correlation, as shown in Table 2. Additionally, considering the gender disparity in the incidence of CHD, we investigated how anxiety and depression levels relate to the fear of disease progression and the levels of social support among genders. Our findings indicated that, in males, higher levels of anxiety and depression were associated with increased fear of disease worsening (P < 0.05) and decreased levels of perceived social support (P < 0.05). Conversely, in females, there was no significant link between anxiety and depression and the fear of disease progression, but there was a negative association with social support scores (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

| Index | HAMA | HAMD | ||

| r | P value | r | P value | |

| Fear of disease progression | ||||

| Physical health dimension | 0.376 | < 0.001 | 0.384 | < 0.001 |

| Social family dimension | 0.219 | 0.017 | 0.185 | 0.044 |

| Total score | 0.349 | < 0.001 | 0.333 | < 0.001 |

| Social support | ||||

| Objective support | -0.392 | < 0.001 | -0.425 | < 0.001 |

| Subjective support | -0.617 | < 0.001 | -0.568 | < 0.001 |

| Utilization degree of support | -0.605 | < 0.001 | -0.584 | < 0.001 |

| Total score | -0.799 | 0.001 | -0.765 | < 0.001 |

| Index | HAMA | HAMD | ||

| r | P value | r | P value | |

| Male | ||||

| Fear of disease progression | 0.354 | 0.001 | 0.350 | 0.001 |

| Social support | -0.805 | < 0.001 | 0.768 | < 0.001 |

| Female | ||||

| Fear of disease progression | 0.336 | 0.087 | 0.273 | 0.169 |

| Social support | -0.776 | < 0.001 | -0.751 | < 0.001 |

The sum of the anxiety and depression scores was used as the dependent variable, whereas the FoP-Q-SF total score and its sub-items and the SSRS total score and its sub-items were used as independent variables. Stepwise regression analysis revealed that fear of disease progression and social support could affect depression and anxiety levels in patients with CHD after surgery (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

| Index | B | SE | B’ | t | P value |

| Constant term | 25.682 | 1.162 | - | 22.100 | < 0.001 |

| Physical health dimension | 0.178 | 0.037 | 0.282 | 4.809 | < 0.001 |

| Social family dimension | 0.077 | 0.032 | 0.127 | 2.423 | 0.017 |

| Objective support | -0.651 | 0.078 | -0.491 | -8.321 | < 0.001 |

| Utilization degree of support | -0.256 | 0.080 | -0.207 | -3.186 | 0.002 |

| Total score of social support | -0.165 | 0.031 | -0.393 | -5.332 | < 0.001 |

The number of individuals with CHD has increased in the past few years. Studies have shown that CHD is currently recognized as a psychosomatic disease, often accompanied by negative emotions such as anxiety and depression. It is a globally recognized disease affecting human health[10]. Coronary artery bypass grafting is an important procedure in the clinical treatment of CHD. It uses the patient’s own blood vessels or vascular substitutes to connect the aorta and distal end of the coronary artery to improve the blood supply to the ischemic site, which can effectively reduce the patient’s clinical symptoms and prolong survival time[11]. However, patients with heart disease have longer recovery periods after coronary artery bypass grafting. Combined with clinical experience in the case of CHD and based on factors such as social support and patients’ fear of disease progression due to insufficient disease cognition, patients have obvious negative emotions, increasing their body burden and thus affecting clinical efficacy[12]. Therefore, in addition to surgical treatment, it is necessary to focus on the psychological state of patients to improve their prognosis.

Relevant research and clinical practice have proven that coronary artery bypass grafting is the main way to treat CHD; given its remarkable effect, it is widely used in clinical practice. However, the surgery is traumatic. After surgery, patients easily fall into emotional traps such as anxiety and depression. The findings of this study revealed that more than 70% of the surveyed patients exhibited symptoms of depression and anxiety. The characteristics of high risk, high trauma, and high cost of coronary artery bypass grafting also cause a series of psychological problems. Negative psychology affects the occurrence, development, treatment, and rehabilitation of heart disease. These two factors are mutually causal and affect disease progression[13]. In the ICU, medical staff generally tend to focus on the short-term treatment effects on patients, sometimes ignoring communication with patients and potentially triggering negative psychological states. The transition period in the ICU indicates that patients with CHD enter the disease rehabilitation stage. The general ward and ICU differ in terms of staffing, working methods, and environment. Patients often experience patient abandonment. If the psychological state of patients is not taken seriously and timely intervention is not carried out, it will negatively affect their prognoses[14,15].

According to the results of this study, there was a strong positive correlation between anxiety, depression, and fear of disease progression (P < 0.05). Consistent with previous research results[16], anxiety and depression in patients had a strong relationship with fear of disease progression, which was confirmed. As CHD is a psychosomatic disorder, many scholars have called for psychological intervention during the biological treatment of patients with CHD[17,18]. After coronary artery bypass grafting, owing to the lack of understanding of coronary artery bypass grafting and disease knowledge among family members and patients, complex psychological reactions, such as fear and pain, will become more intense. Moreover, most patients remain in bed for a long time after hospitalization. The reduction in activity and comorbid chronic conditions (such as hypertension and diabetes) can lead to a heightened fear of disease progression and may worsen preexisting health conditions[19]. In individuals with anxiety and depression, apprehension can impair the regulatory functions of the immune system, leading to a marked increase in the risk of complications. Consequently, healthcare professionals must implement psychological interventions to mitigate these adverse emotional effects on patients. Nonetheless, correlation analysis among patients of varying genders revealed no connection between female patients’ anxiety and depression and their fear of disease progression. It is hypothesized that this may be attributed to the tendency of female patients with CHD to focus more on immediate physical well-being and psychological comfort rather than the disease’s long-term outcome.

During the ICU transition period, patients with CHD face various challenges such as disease instability, exposure to complex medical equipment and treatment procedures, and separation from their families. These factors may lead to negative emotions such as anxiety and depression. At the same time, due to the uncertainty of postoperative rehabilitation, patients may be concerned about their health status, which increases the psychological burden[20]. According to the results of this study, there was a strong negative correlation between anxiety, depression, and social support (P < 0.05). Social support became particularly important during this period. Support from family members, friends, medical staff, etc., can help patients reduce bad moods and enhance their rehabilitation confidence. According to existing research, CHD is closely associated with psychosocial factors. The mental health of patients has a crucial impact on the prognosis of their condition[21,22]. Good social support can improve patients’ quality of life by alleviating their psychologically bad moods and promoting the rehabilitation process. In contrast, a lower level of social support may increase the psychological burden on patients and affect the rehabilitation effect. Therefore, during the ICU transition period after coronary artery bypass grafting, we should attach importance to social support; strengthen communication and exchanges between patients and family members, friends, and medical staff; and provide patients with comprehensive support and assistance to promote their mental health and rehabilitation[23]. This was a single-center study, and the potential selection biases within the sample size are acknowledged, which may constrain the generalizability of our findings. Moving forward, we intend to embark on a broader, multi-site study with an expanded sample size. We will employ diverse methodologies to assess patient psychological well-being and monitor the evolution of psychological variables and their rehabilitation outcomes longitudinally. The use of such an approach aims to bolster the robustness and reliability of our research outcomes.

In summary, the levels of anxiety and depression in patients in the ICU transitional period after CHD surgery were positively correlated with the progression of fear of the disease and negatively correlated with the level of social support. Therefore, during the ICU transition period, one not only needs to keep a watchful eye on the patient’s condition changes but also needs to communicate effectively with patients and their families, explain the condition and treatment plan, improve their social support level, and alleviate the patient’s fear of disease progression to help reduce their anxiety and fear. This study selected only retrospective data from a single hospital, and the sample size may have had some deviations in selection and collection. In the future, we plan to conduct a multicenter study with a large sample size to further confirm the reliability of our findings.

| 1. | Liang F, Wang Y. Coronary heart disease and atrial fibrillation: a vicious cycle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;320:H1-H12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lehto HR, Winell K, Pietilä A, Niiranen TJ, Lommi J, Salomaa V. Outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting and percutaneous coronary intervention in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2022;8:692-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Meissner VH, Olze L, Schiele S, Ankerst DP, Jahnen M, Gschwend JE, Herkommer K, Dinkel A. Fear of cancer recurrence and disease progression in long-term prostate cancer survivors after radical prostatectomy: A longitudinal study. Cancer. 2021;127:4287-4295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sharpe L, Richmond B, Todd J, Dudeney J, Dear BF, Szabo M, Sesel AL, Forrester M, Menzies RE. A cross-sectional study of existential concerns and fear of progression in people with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Psychosom Res. 2023;175:111514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Denson JL, Knoeckel J, Kjerengtroen S, Johnson R, McNair B, Thornton O, Douglas IS, Wechsler ME, Burke RE. Improving end-of-rotation transitions of care among ICU patients. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29:250-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fan JQ, Lu WJ, Tan WQ, Liu X, Wang YT, Wang NB, Zhuang LX. Effectiveness of Acupuncture for Anxiety Among Patients With Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2232133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang J, Song Z, Gui C, Jiang G, Cheng W, You W, Wang Z, Chen G. Treatments to post-stroke depression, which is more effective to HAMD improvement? A network meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1035895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mahendran R, Liu J, Kuparasundram S, Griva K. Validation of the English and simplified Mandarin versions of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire - Short Form in Chinese cancer survivors. BMC Psychol. 2020;8:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li Y, Zhang XW, Liao B, Liang J, He WJ, Liu J, Yang Y, Zhang YH, Ma T, Wang JY. Social support status and associated factors among people living with HIV/AIDS in Kunming city, China. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ohlow MA, Winterhalter M. Coronary Heart Disease-A Protracted Treatment Course. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2023;120:98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bianco V, Kilic A, Gleason TG, Aranda-Michel E, Wang Y, Navid F, Sultan I. Timing of coronary artery bypass grafting after acute myocardial infarction may not influence mortality and readmissions. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;161:2056-2064.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Arsyi DH, Permana PBD, Karim RI, Abdurachman. The role of optimism in manifesting recovery outcomes after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2022;162:111044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Harshfield EL, Pennells L, Schwartz JE, Willeit P, Kaptoge S, Bell S, Shaffer JA, Bolton T, Spackman S, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kee F, Amouyel P, Shea SJ, Kuller LH, Kauhanen J, van Zutphen EM, Blazer DG, Krumholz H, Nietert PJ, Kromhout D, Laughlin G, Berkman L, Wallace RB, Simons LA, Dennison EM, Barr ELM, Meyer HE, Wood AM, Danesh J, Di Angelantonio E, Davidson KW; Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Association Between Depressive Symptoms and Incident Cardiovascular Diseases. JAMA. 2020;324:2396-2405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 49.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhan Y, Yu J, Chen Y, Liu Y, Wang Y, Wan Y, Li S. Family caregivers' experiences and needs of transitional care during the transfer from intensive care unit to a general ward: A qualitative study. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30:592-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ji J, Yang L, Yang H, Jiang Y, Tang P, Lu Q. Parental experience of transition from a paediatric intensive care unit to a general ward: A qualitative study. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30:3578-3588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kolsteren EEM, Deuning-Smit E, Chu AK, van der Hoeven YCW, Prins JB, van der Graaf WTA, van Herpen CML, van Oort IM, Lebel S, Thewes B, Kwakkenbos L, Custers JAE. Psychosocial Aspects of Living Long Term with Advanced Cancer and Ongoing Systemic Treatment: A Scoping Review. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Blumenthal JA, Smith PJ, Jiang W, Hinderliter A, Watkins LL, Hoffman BM, Kraus WE, Liao L, Davidson J, Sherwood A. Effect of Exercise, Escitalopram, or Placebo on Anxiety in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease: The Understanding the Benefits of Exercise and Escitalopram in Anxious Patients With Coronary Heart Disease (UNWIND) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:1270-1278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Su JJ, Yu DS. Effects of a nurse-led eHealth cardiac rehabilitation programme on health outcomes of patients with coronary heart disease: A randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;122:104040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chaudhury S, Saini R, Bakhla AK, Singh J. Depression and Anxiety following Coronary Artery Bypass Graft: Current Indian Scenario. Cardiol Res Pract. 2016;2016:2345184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ruel M, Williams A. A New Effect Modifier of the Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Versus Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Decision: Physical and Mental Functioning. Circulation. 2022;146:1281-1283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Miao Jonasson J, Hendryx M, Shadyab AH, Kelley E, Johnson KC, Kroenke CH, Garcia L, Lawesson S, Santosa A, Sealy-Jefferson S, Lin X, Cene CW, Liu S, Valdiviezo C, Luo J. Social Support, Social Network Size, Social Strain, Stressful Life Events, and Coronary Heart Disease in Women With Type 2 Diabetes: A Cohort Study Based on the Women's Health Initiative. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:1759-1766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rometsch S, Greutmann M, Latal B, Bernaschina I, Knirsch W, Schaefer C, Oxenius A, Landolt MA. Predictors of quality of life in young adults with congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2019;5:161-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Vodermaier A, Linden W. Social support buffers against anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with cancer only if support is wanted: a large sample replication. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:2345-2347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |