Published online Nov 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i11.1681

Revised: September 6, 2024

Accepted: October 10, 2024

Published online: November 19, 2024

Processing time: 166 Days and 21.3 Hours

Neurodiverse students frequently encounter distinct challenges that can adversely affect their mental well-being. This research aimed to investigate emotional distress, depression, and anxiety among neurodiverse students, examine the inter

To address the problem of lack of data pointed out in the neurodiversity research in Nigeria, this study aims to examine the emotional distress, depression, and anxiety in neurodiverse students.

A cross-sectional study was carried out involving 200 neurodiverse students in Nigeria. Participants filled out self-report questionnaires that measured emotional distress (Brief Emotional Distress Scale for Youth), depression (Center for Epi

Anxiety was found to have the highest prevalence (mean = 68.8), followed by depression (mean = 34.2) and emotional distress (mean = 26.3). Significant positive correlations were identified among all three mental health factors, with the strongest correlation observed between depression and anxiety (rho = 0.492, P < 0.001). Moderate evidence indicated gender differences in emotional distress (BF10 = 2.448). The interaction between educational environment and diagnosis had a significant effect on emotional distress (F = 3.106, P = 0.017). Kruskal-Wallis tests indicated significant variations in anxiety levels across different educational settings (P = 0.002), although post-hoc comparisons did not reveal significant differences among specific settings.

This research emphasizes the prevalence of mental health challenges among neurodiverse students, particularly concerning anxiety. The intricate relationships among emotional distress, depression, and anxiety highlight the necessity for thorough mental health support. The impact of educational settings and diagnoses on mental health outcomes stresses the importance of customized interventions. These findings are significant for educators, mental health professionals, and policymakers in formulating targeted support strategies for neurodiverse students.

Core Tip: This cross-sectional study involving 200 neurodiverse students in Nigeria indicates a notable prevalence of anxiety, followed by depression and emotional distress. The study identified significant positive correlations among these mental health issues, with the most pronounced relationship observed between depression and anxiety. Gender disparities were noted in emotional distress, and the interplay between educational environment and diagnosis had a significant impact on levels of emotional distress. Variations in anxiety levels were also evident across different educational settings. These results emphasize the intricate mental health requirements of neurodiverse students and highlight the necessity for customized interventions that take into account individual diagnoses, educational setting, and gender. The findings offer essential insights for educators, mental health professionals, and policymakers in formulating targeted support strategies for this demographic.

- Citation: Otu MS, Sefotho MM. Examination of emotional distress, depression, and anxiety in neurodiverse students: A cross-sectional study. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(11): 1681-1695

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i11/1681.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i11.1681

In recent years, there has been a noticeable increase in the number of neurodiverse students worldwide, including those in sub-Saharan Africa. These students exhibit variations in their neurocognitive function and require specific support and accommodations to succeed academically[1]. Neurodiversity encompasses conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and specific learning disabilities (SLD)[2]. Research indicates that neurodiverse students are more likely to experience additional mental health conditions, including emotional distress, depression, and anxiety[3,4]. These conditions can manifest because of their difficulties in managing their neurodiverse conditions[5-7].

Also, research indicated that while these students often have unique strengths and abilities, they frequently encounter difficulties in academic and social settings[8,9]. The combination of social, emotional, and educational challenges, along with the lifelong persistence of these issues, puts neurodiverse students at a heightened risk[10,11]. As a result, they have difficulties coping with normal conditions of life, especially when they are exposed to stressful events[12]. Moreover, neurodiverse students may have difficulties in sensorimotor functioning, emotional codes, communication, and cognition, albeit causing emotional distress[13]. These symptoms can significantly impact their overall well-being and hinder their ability to navigate the challenges of college life. According to McKenney et al[14], students with a neuro

Despite growing awareness of neurodiversity in education, there is a significant lack of empirical data on the mental health of neurodiverse students in Nigeria. Research on the prevalence, challenges, and mental health needs of these students is scarce, limiting the development of tailored interventions and support systems. The absence of robust data hinders efforts to address the specific needs of neurodiverse students in Nigeria, making it difficult for policymakers, educators, and healthcare professionals to effectively support this population. This study highlights the urgent need for comprehensive research to fill these gaps and ensure inclusive education for neurodiverse students.

To address the problem of lack of data pointed out in the neurodiversity research in Nigeria, this study aims to examine the emotional distress, depression, and anxiety in neurodiverse students. Specifically, this study focused on two objectives.

Objective 1: The primary objective of this study is to determine the prevalence of emotional distress, depression, and anxiety among neurodiverse students.

Objective 2: The secondary objective of this study is to explore the relationships between emotional distress, depression, and anxiety among neurodiverse students.

Objective 3: Another secondary objective of this study is to investigate the impact of participants' characteristics (gender, educational setting, and diagnosis) on emotional distress, depression, and anxiety.

The sample of the study included 200 neurodiverse students from diverse backgrounds. The participants were selected through convenience and purposive sampling. Convenience sampling was employed to ensure a diverse representation of neurodiverse students from various educational institutions. This approach allowed for the inclusion of participants who were easily accessible and willing to participate in the study. In addition, purposive sampling was employed to ensure the inclusion of participants who had specific characteristics relevant to the study. For example, participants with specific types of neurodiverse conditions, such as ASD, ADHD, or SLD, were targeted to enhance the study's validity and applicability. Score distributions were examined for normality using Shapiro-Wilk tests and visual inspection of histograms. While the overall sample approximated normal distributions, the small SLD subgroup (n = 8) showed some non-normality as expected. Non-parametric tests were used for analyses involving this subgroup.

Ethical considerations: Researchers adhered to ethical guidelines set by the relevant institutional review boards and all applicable regulations. The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and applicable laws and regu

Before participating in the study, all participants 18 years old signed an informed consent form and those below 18 years got their parents or legal guardians to sign the form. The informed consent form detailed the purpose, procedures, and potential risks and benefits of the study. Also, participants reporting severe symptoms or suicidal ideation were provided with mental health resources and referrals. No adverse events were reported as a result of study participation.

Participants completed self-report questionnaires that assessed emotional distress, depression, and anxiety. The questionnaires included validated and reliable measures such as the Brief Emotional Distress Scale for Youth (BEDSY), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised (CESD-R10), and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). The BEDSY measures emotional distress, and the CESD-R10 and STAI assess depression and anxiety, respectively.

The BEDSY: The BEDSY is a brief self-report scale that measures the emotional distress of young people. The current version of BEDSY which was developed and validated by Spence and Rapee[15] has eight items that are measured on a four-point scale of Never, Sometimes, Often, and Always. The items include: "I feel really sad", "I feel nervous", "I feel alone", "I worry that something bad will happen to me", "I feel like there is nothing to look forward to", and "I feel afraid". "I just don't enjoy things anymore", and all of a sudden, I feel really scared for no reason at all." There was strong internal consistency, acceptable construct validity, and acceptable sensitivity and specificity on BEDSY in discriminating between a community sample and anxious youth[15]. In the present study, the BEDSY had an internal consistency coefficient of 0.70 when tested with a sample of neurodiverse students. The BEDSY is commonly used in conjunction with other assessment tools to gain a comprehensive understanding of an individual's emotional well-being. It can provide insights into the severity and impact of emotional distress, enabling appropriate support and intervention.

CESD-R10: The purpose of the CESD-R10 is to assess the presence of depressive symptoms in a population. It is a widely used screening tool to identify individuals who may be experiencing symptoms of depression. The scale aims to gather information about an individual's mood, thoughts, and behaviors related to depression. The CESD-R10 had 10 items structured in a four-point response format of Rarely (less than 1 day), Some of the time (1-2 days), Occasionally (3-4 days), and All of the time (5-7 days). The items of this instrument include "I was bothered by things that usually don't bother me", "I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing", "I felt depressed", and "I felt hopeful about the future" among others. The total score of CESD-R10 is calculated by adding all 10 items together. If more than two items are missing, the form is not usually scored. Moreover, scores equal to or above 10 are considered depression scores[16]. Various studies have shown that CESD-R10 has high validity and reliability[16-20]. When assessing the neurodivergent student population in the current study, the internal consistency reliability coefficient of the scale is 0.77. This was considered high and significant for the present study.

The STAI: The STAI was developed by Spielberger et al[21] to assess trait and state anxiety. This questionnaire contains 20 items assessing trait anxiety, including: "I am anxious; I am worried" "I feel calm; I feel secure"; "I worry too much about something that is not important" and "I am content; I am a steady person". The items are rated on a 4-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety. Based on (Spielberger et al[21]), internal consistency coefficients ranged between 0.86 and 0.95, while test-retest reliability coefficients ranged from 0.65 to 0.75 over two months. The internal consistency coefficient for this measure in the present study is 0.846. Significant evidence indicates that the scale is both constructive and concurrently valid (Spielberger[22], in 1989; Thomas and Cassady[23]).

The analysis commenced with the application of descriptive statistics to establish a foundational understanding of the sample. A binomial test was performed to investigate the distribution of categorical variables, including gender, educational setting, and diagnosis. To evaluate the normality of data distribution for these variables, the Shapiro-Wilk test was utilized.

For the primary mental health outcomes-emotional distress, depression, and anxiety-central tendency and variability measures were computed, encompassing mean, standard deviation, and range. Density plots were generated to illustrate the distribution of scores for each outcome. To examine the relationships among the mental health factors, Spearman's rho correlation coefficients were calculated. A correlation plot was created to visually depict these relationships, thereby elucidating the interconnections among emotional distress, depression, and anxiety. Gender disparities in mental health outcomes were assessed using Bayesian Mann-Whitney U Tests, facilitating a detailed interpretation of the evidence regarding gender differences in each outcome. To evaluate the impact of educational settings and diagnosis on mental health outcomes, two-way ANOVAs were conducted. These analyses explored the main effects of each factor as well as any potential interaction effects. In addition, Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed as a non-parametric alternative to compare outcomes across various educational settings and diagnoses.

In instances where significant differences were identified, post-hoc comparisons were executed to determine specific group differences. For example, pairwise comparisons were conducted among different educational settings to identify where anxiety levels exhibited significant variation.

Throughout the analytical process, meticulous attention was given to the assumptions inherent in each statistical test. In cases where data did not meet normality assumptions, non-parametric alternatives were utilized. The Bayesian analysis incorporated data augmentation algorithms with multiple chains and iterations to ensure the reliability of the results.

Table 1 presents the results of a binomial test conducted on various categorical variables in this study. The study included a nearly balanced distribution of males and females. Out of 200 participants, 95 were male (47.5%) and 105 were female (52.5%). The proportion of females (0.525) was slightly higher than males, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.525). The 95% confidence intervals for both genders overlap, further indicating no significant difference in gender representation. The participants were distributed across three types of educational settings; Mainstream schools: 86 participants (43%); Special education schools: 78 participants (39%); and Alternative learning environments: 36 participants (18%). The distribution across these settings was not uniform. Mainstream schools had the highest representation, while alternative learning environments had the lowest. The P values for special education schools (P = 0.002) and alternative learning environments (P < 0.001) indicate that their proportions were significantly different from the test value of 0.5. The study included participants with three different diagnoses: ASD - 114 participants (57%); ADHD - 78 participants (39%); and SLD - 8 participants (4%). ASD was the most prevalent diagnosis in the sample, followed by ADHD, while SLD had a notably lower representation. The proportions for ADHD (P = 0.002) and SLD (P < 0.001) were significantly different from the test value of 0.5. It's important to note that the binomial test was conducted against a test value of 0.5 for all categories. This means the test was comparing each proportion to an expected 50% split. The P values indicate whether the observed proportions significantly differ from this expected even split.

| Variable | Level | Counts | Total | Proportion | P value | 95%CI for proportion | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Gender | Male | 95 | 200 | 0.475 | 0.525 | 0.404 | 0.547 |

| Female | 105 | 200 | 0.525 | 0.525 | 0.453 | 0.596 | |

| Educational setting | Mainstream schools | 86 | 200 | 0.43 | 0.056 | 0.36 | 0.502 |

| Special education schools | 78 | 200 | 0.39 | 0.002 | 0.322 | 0.461 | |

| Alternative learning environments | 36 | 200 | 0.18 | < 0.001 | 0.129 | 0.24 | |

| Diagnosis | ASD | 114 | 200 | 0.57 | 0.056 | 0.498 | 0.64 |

| ADHD | 78 | 200 | 0.39 | 0.002 | 0.322 | 0.461 | |

| SLD | 8 | 200 | 0.04 | < 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.077 | |

In summary, the study sample showed a balanced gender distribution, a preference for mainstream and special education settings over alternative learning environments, and a higher prevalence of ASD and ADHD diagnoses compared to SLD. These findings provide insights into the characteristics of the study population and may have implications for interpreting other results from this research.

In Table 2, Shapiro-Wilk Statistic has a value ranging from 0 to 1. A value closer to 1 indicates that the data is more likely to be normally distributed. In our results: Gender: 0.636; educational setting: 0.784; and diagnosis: 0.697.

| Shapiro-Wilk | P value of Shapiro-Wilk | |

| Gender | 0.636 | < 0.001 |

| Educational setting | 0.784 | < 0.001 |

| Diagnosis | 0.697 | < 0.001 |

The P value helps determine the statistical significance of the test. A common threshold for significance is 0.05. If the P value is less than this threshold, it suggests that the data significantly deviates from a normal distribution. In our results, all p-values are less than 0.001, which is much lower than the typical significance level of 0.05. This indicates that for all the variables (gender, educational setting, and diagnosis), the null hypothesis of normality is rejected. In other words, the data for each of these variables does not follow a normal distribution. These findings suggest that non-parametric methods might be more appropriate for analyzing these variables, as they do not assume normality.

Based on the provided descriptive statistics in Table 3, we can interpret the key findings for the three variables: Emotional Distress, Depression, and Anxiety. The sample size for all three variables is 200 valid observations, which provides a substantial basis for analysis. One of the first things to note is that none of the variables are normally distributed, as indicated by the Shapiro-Wilk test results (P < 0.001 for all variables). This non-normality should be considered when selecting appropriate statistical methods for further analysis.

| Emotional distress | Depression | Anxiety | |

| Valid | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Mean | 26.27 | 34.25 | 68.815 |

| SD | 4.002 | 6.32 | 8.82 |

| Shapiro-Wilk | 0.884 | 0.831 | 0.742 |

| P value of Shapiro-Wilk | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Minimum | 14 | 18 | 37 |

| Maximum | 32 | 40 | 77 |

| 25th percentile | 23 | 30 | 66 |

| 50th percentile | 26.5 | 36 | 73 |

| 75th percentile | 30 | 40 | 75 |

Looking at the central tendency and variability, we can see that Emotional Distress has a mean score of 26.270 with a standard deviation of 4.002. This suggests that, on average, participants experience moderate levels of emotional distress, with some variability in scores. Depression shows a higher mean score of 34.250 and a larger standard deviation of 6.320. This indicates that depression levels are generally higher than emotional distress, and there's more variability among participants in terms of depressive symptoms. Anxiety stands out with the highest mean score of 68.815 and the largest standard deviation of 8.820. This suggests that anxiety levels are generally higher than both emotional distress and depression, and there is considerable variability in anxiety scores among the participants.

Examining the range and percentiles provides additional insights. Emotional distress scores range from 14 to 32, with a median of 26.500. The interquartile range (IQR) spans from 23 (25th percentile) to 30 (75th percentile). Depression scores have a wider range, from 18 to 40, with a median of 36.000. The IQR for depression is from 30 to 40, indicating that half of the participants scored within this range. Anxiety shows the widest range, from 37 to 77, with a median of 73.000/interestingly, the IQR for anxiety is relatively small (66 to 75) compared to its overall range. This suggests that while there are some extremely low scores, the majority of participants report high levels of anxiety.

These findings provide treasured insights into the mental health profile of neurodiverse students. Anxiety appears to be the most prevalent issue, with the highest mean and median scores, as well as the widest range of scores. Depression scores are generally higher than emotional distress scores, suggesting that depressive symptoms may be more pronounced than general emotional distress in this sample. The relatively small standard deviation and range for emotional distress compared to depression and anxiety suggest more consistency in general emotional distress levels across the sample. In contrast, the larger standard deviations for depression and especially anxiety indicate greater variability in these specific symptoms among participants. These findings are further illustrated graphically.

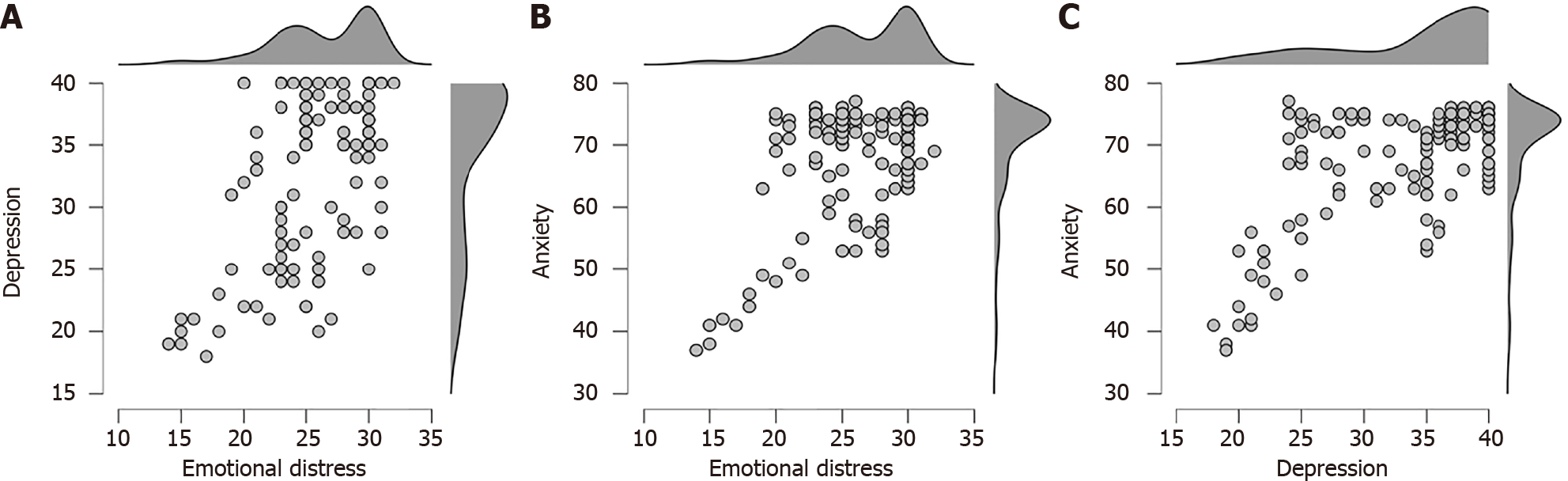

The plot in Figure 1A shows a bimodal distribution, meaning there are two distinct peaks or groups. One peak is around the 20-25 range, and another higher peak appears closer to the 30-35 range. This suggests that while some neurodiverse students experience moderate emotional distress, there is a larger group that reports higher levels of emotional distress.

In Figure 1B, there seems to be a similar pattern of distribution as in Figure 1A, with peaks indicating groups of neurodiverse students experiencing moderate to severe depression. Without seeing the precise plot, depression is likely shown to affect neurodiverse students differently, with varying degrees of severity.

In Figure 1C, anxiety distribution likely follows a pattern similar to that of emotional distress and depression. Peaks in the graph show different clusters of neurodiverse students experiencing moderate and higher levels of anxiety.

In summary, the three plots indicate that the neurodiverse population exhibits clusters of individuals facing varying degrees of mental health challenges, with certain individuals categorized as experiencing higher levels of distress. This insight is essential for customizing interventions aimed at addressing both moderate and severe mental health concerns within the population.

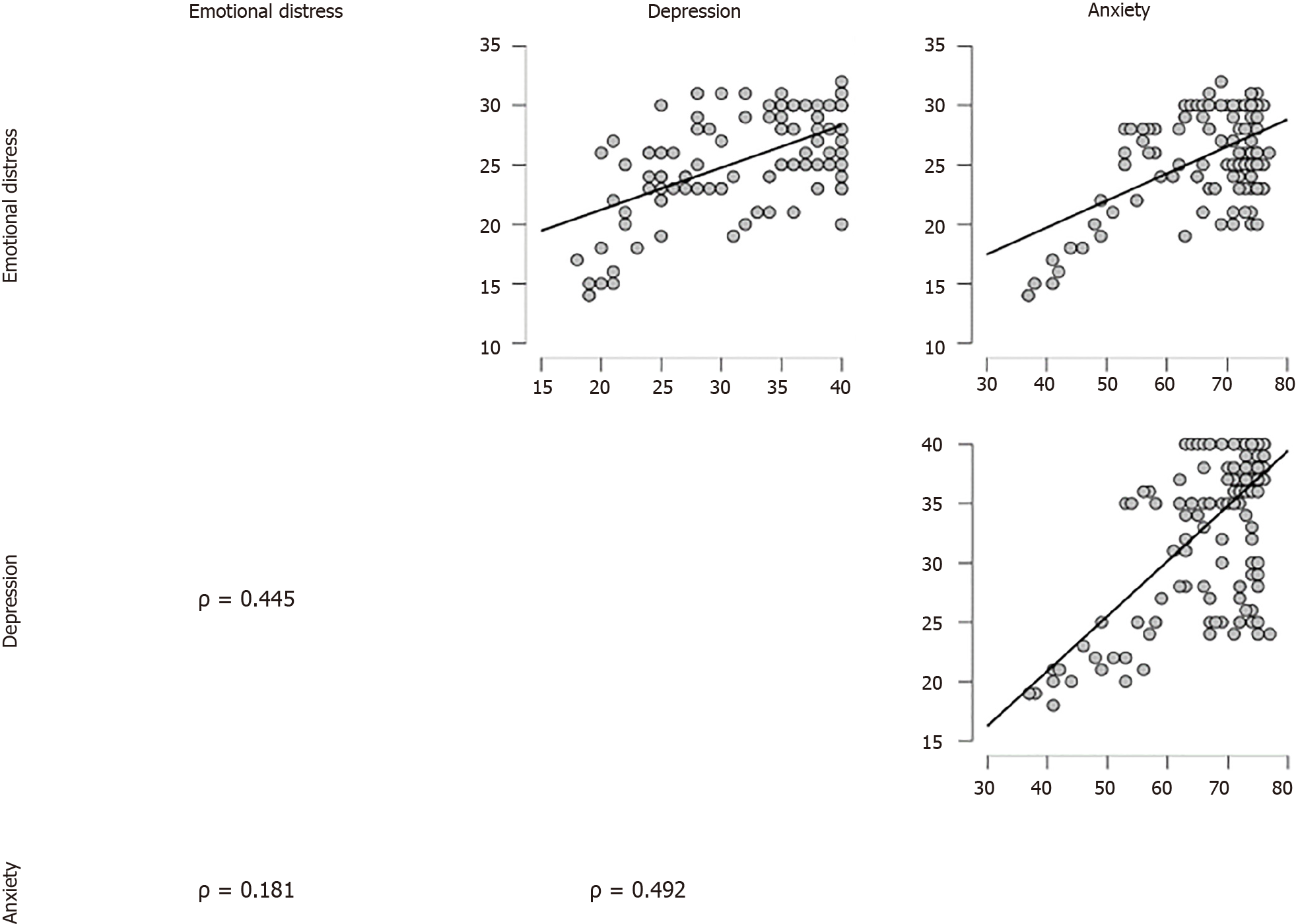

The results presented in Table 4 provide valued insights into the relationships between emotional distress, depression, and anxiety. The data reveals significant correlations among all three variables, suggesting they are interconnected aspects of psychological well-being. The strongest correlation observed is between depression and anxiety, with a Spearman's rho of 0.492 (P < 0.001). This moderate to strong positive relationship indicates that individuals experiencing higher levels of depression are likely also to report higher levels of anxiety, and vice versa. This finding aligns with clinical observations of frequent comorbidity between depressive and anxiety disorders. Furthermore, emotional distress shows a moderate positive correlation with depression (rho = 0.445, P < 0.001). This suggests that as emotional distress increases, depressive symptoms tend to increase as well. The relationship between emotional distress and depression is stronger than the relationship between emotional distress and anxiety. Also, the correlation between emotional distress and anxiety, while still statistically significant (P = 0.010), is notably weaker (rho = 0.181). This weaker association suggests that while there is some overlap between emotional distress and anxiety, other factors may play a more substantial role in anxiety experiences.

These findings have important implications for understanding the relationship between these psychological constructs. The strong link between depression and anxiety underlines the importance of considering both when assessing and treating mental health concerns. The moderate relationship between emotional distress and depression suggests that interventions targeting emotional regulation might be particularly beneficial for individuals experiencing depressive symptoms. However, it is critical to note that while these correlations indicate associations between the variables, they do not imply causation. The relationships observed could be bidirectional or influenced by other factors not captured in this analysis. In addition, the strength of these correlations suggests that while these constructs are related, they are distinct enough to warrant separate consideration in both research and clinical practice.

Upon closer examination of Figure 2, we are presented with a correlation plot that offers respected insights into the relationships between emotional distress, depression, and anxiety among neurodiverse students. This visualization provides a nuanced perspective on the interconnectedness of these mental health factors within this specific student population. The correlation plot displays the strength and direction of relationships between the three variables: Emotional distress, depression, and anxiety. Each variable is typically represented along both axes, creating a matrix of correlation coefficients. The intensity of each cell in the matrix indicates the strength of the correlation, with darker or more saturated colors suggesting stronger relationships.

One of the most striking aspects of this correlation plot is the strong positive correlation between all three variables. This suggests that as one mental health challenge increases in severity, the others tend to follow suit. For instance, students experiencing higher levels of emotional distress may also report elevated symptoms of depression and anxiety. This interconnectedness underlines the complex nature of mental health and the potential for compounding effects among these factors.

The Bayesian Mann-Whitney U Test presented in Table 5 provides insights into the potential impact of gender on emotional distress, depression, and anxiety among neurodiverse students. This analysis offers a nuanced perspective on gender differences in mental health outcomes within this specific population. The Bayes Factor (BF10) for emotional distress is 2.448, which suggests moderate evidence in favor of a gender difference. This indicates that there is some support for the hypothesis that gender impacts emotional distress levels among neurodiverse students. The W statistic of 3971.500 represents the sum of ranks for one of the gender groups, providing information about the distribution of scores. For depression, the BF10 is 0.852, which is slightly below 1. This suggests that there is weak evidence against a gender difference in depression levels. In other words, the data does not strongly support the idea that gender significantly impacts depression among neurodiverse students. The W statistic of 4314.000 again represents the sum of ranks for one gender group. The anxiety results show a BF10 of 0.842, which is similar to the depression results. This also indicates weak evidence against a gender difference in anxiety levels. The data does not provide strong support for the hypothesis that gender significantly impacts anxiety among neurodiverse students. The W statistic for anxiety is 4440.500.

| BF10 | W | Rhat | |

| Emotional distress | 2.448 | 3971.5 | 1.002 |

| Depression | 0.852 | 4314 | 1 |

| Anxiety | 0.842 | 4440.5 | 1.002 |

The Rhat values for all three measures are very close to 1 (1.002, 1.000, and 1.002 respectively), indicating good convergence of the Markov chains used in the Bayesian analysis. This suggests that the results are reliable from a computational standpoint. It's important to note that these results are based on a data augmentation algorithm with 5 chains of 1000 iterations, which adds robustness to the analysis. In interpreting these results, we can conclude that there is moderate evidence for gender differences in emotional distress among neurodiverse students, but weak evidence for such differences in depression and anxiety. This suggests that while gender may play a role in overall emotional distress, its impact on specific manifestations of depression and anxiety is less pronounced in this population.

The analysis of emotional distress across different educational settings and diagnoses in Table 6 and Table 7 reveals some interesting findings. Starting with the two-way ANOVA, we observe that neither Educational Setting nor Diagnosis alone has a statistically significant effect on Emotional Distress. The F value for Educational Setting is 0.680 with a P value of 0.508, while for Diagnosis, the F value is 1.778 with a P value of 0.172. These results suggest that when considered independently, neither the type of educational setting nor the specific diagnosis significantly influences the level of emotional distress experienced by neurodiverse students in this study. However, the most intriguing finding comes from the interaction effect between educational setting and diagnosis. This interaction is statistically significant, with an F value of 3.106 and a P value of 0.017. This suggests that the impact of educational setting on emotional distress varies depending on the diagnosis, or conversely, that the effect of diagnosis on emotional distress differs across educational settings.

| Cases | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | P value |

| Educational setting | 20.279 | 2 | 10.14 | 0.68 | 0.508 |

| Diagnosis | 53.062 | 2 | 26.531 | 1.778 | 0.172 |

| Educational setting1 diagnosis | 185.33 | 4 | 46.333 | 3.106 | 0.017 |

| Residuals | 2849.394 | 191 | 14.918 |

| Factor | Statistic | df | P value |

| Educational setting | 4.996 | 2 | 0.082 |

| Diagnosis | 4.188 | 2 | 0.123 |

The Kruskal-Wallis tests, which are non-parametric alternatives to one-way ANOVA, support the findings from the ANOVA regarding the main effects. For Educational Setting, the test statistic is 4.996 with a P value of 0.082, and for Diagnosis, the test statistic is 4.188 with a P value of 0.123. These results align with the ANOVA, showing no significant differences in emotional distress across either educational settings or diagnoses when considered independently.

The analysis of depression across different educational settings and diagnoses presented in Table 8 and Table 9 reveals no statistically significant effects. The ANOVA results show that neither educational setting (F = 0.784, P = 0.458) nor diagnosis (F = 1.625, P = 0.200) has a significant main effect on depression levels. In addition, the interaction between educational setting and diagnosis is also not significant (F = 1.156, P = 0.332). These findings suggest that, in this study, the type of educational setting and the specific diagnosis do not independently or jointly influence depression levels among the participants. This is somewhat surprising, as one might expect different educational environments or diagnoses to impact depression differently.

| Cases | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | P value |

| Educational setting | 59.334 | 2 | 29.667 | 0.784 | 0.458 |

| Diagnosis | 122.937 | 2 | 61.469 | 1.625 | 0.2 |

| Educational setting1 diagnosis | 174.927 | 4 | 43.732 | 1.156 | 0.332 |

| Residuals | 7225.005 | 191 | 37.827 |

| Factor | Statistic | df | P value |

| Educational setting | 5.205 | 2 | 0.074 |

| Diagnosis | 1.379 | 2 | 0.502 |

The Kruskal-Wallis tests, which are non-parametric alternatives to one-way ANOVA, support these findings. For Educational Setting, the test statistic is 5.205 with a P value of 0.074, and for diagnosis, the test statistic is 1.379 with a P value of 0.502. While the P value for educational settings is close to the conventional significance threshold of 0.05, it still indicates no significant difference in depression across different educational settings. It's important to note that these results don't mean that depression is unrelated to educational settings or diagnoses. Rather, they suggest that in this particular sample and study design, no significant relationships were detected. other factors not accounted for in this analysis might be influencing depression levels, or the relationships might be more complex than what these tests can reveal.

From Table 10 and Table 11, the analysis of anxiety across different educational settings and diagnoses presents an intriguing contrast between the ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis test results. The ANOVA findings suggest no significant effects of educational setting (F = 1.032, P = 0.358), diagnosis (F = 0.601, P = 0.549), or their interaction (F = 1.783, P = 0.134) on anxiety levels. This implies that neither the type of educational environment nor the specific diagnosis, independently or in combination, significantly influences anxiety among the participants in this study. However, the Kruskal-Wallis test results paint a different picture, particularly for Educational settings. While the test confirms no significant effect of diagnosis on anxiety (statistic = 1.495, P = 0.474), it reveals a highly significant difference in anxiety levels across educational settings (statistic = 12.459, P = 0.002). This discrepancy between the ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis results for educational settings is noteworthy and warrants further investigation. The conflicting outcomes could be due to several factors. The Kruskal-Wallis test, being non-parametric, might be more sensitive to differences in the data that don't meet the assumptions of ANOVA. It's possible that the relationship between Educational Setting and Anxiety is non-linear or that the data distribution violates ANOVA assumptions.

| Cases | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | P value |

| Educational setting | 145.56 | 2 | 72.78 | 1.032 | 0.358 |

| Diagnosis | 84.696 | 2 | 42.348 | 0.601 | 0.549 |

| Educational setting1 diagnosis | 502.701 | 4 | 125.675 | 1.783 | 0.134 |

| Residuals | 13465.03 | 191 | 70.498 |

| Factor | Statistic | df | P value |

| Educational setting | 12.459 | 2 | 0.002 |

| Diagnosis | 1.495 | 2 | 0.474 |

These results highlight the importance of using multiple statistical approaches when analyzing complex data. The significant Kruskal-Wallis result for educational settings suggests that there may indeed be meaningful differences in anxiety levels across different educational environments, even though these differences weren't captured by the ANOVA. To clarify this, post-hoc tests following the Kruskal-Wallis were conducted to help identify which specific educational settings differ significantly from each other in terms of anxiety levels.

The post-hoc comparisons for Educational Settings, averaged across all diagnoses, reveal no statistically significant differences in anxiety levels between the three types of educational environments (Table 12). Mainstream schools show slightly lower anxiety levels compared to both special education schools (mean difference = -3.480) and alternative learning environments (mean difference = -3.598). However, these differences are not statistically significant, with P values of 0.411 and 0.414 respectively. The comparison between special education schools and alternative learning environments shows a minimal difference (mean difference = -0.118), which is far from statistical significance (P = 0.999). These results suggest that, on average, the type of educational setting alone does not significantly impact anxiety levels among students. This finding is interesting as it indicates that factors other than the broad category of the educational environment may be more influential in determining student anxiety levels. It's important to note that these results are averaged across all diagnoses, which means that potential differences that might exist for specific diagnostic groups are not reflected in these comparisons. The lack of significant differences between educational settings highlights the complexity of factors influencing student anxiety and suggests that a one-size-fits-all approach to educational placement may not be sufficient when considering student well-being. Further investigation into how educational settings interact with other factors, such as specific diagnoses or individual student characteristics, could provide more nuanced insights into optimizing educational environments for different student groups.

| Mean difference | SE | t | PTukey | ||

| Mainstream schools | Special education schools | -3.48 | 2.728 | -1.276 | 0.411 |

| Alternative learning environments | -3.598 | 2.835 | -1.269 | 0.414 | |

| Special education schools | Alternative learning environments | -0.118 | 2.584 | -0.046 | 0.999 |

The purpose of this study was to fulfill three main objectives: First, to assess the prevalence of emotional distress, depression, and anxiety in neurodiverse students; second, to examine the interrelationships among these mental health issues; and third, to analyze how the characteristics of participants, including gender, educational environment, and diagnosis, influence emotional distress, depression, and anxiety. The results offer beneficial insights into these aims and enhance the understanding of mental health within neurodiverse communities. The findings revealed that anxiety exhibited the highest prevalence (mean = 68.8), followed by depression (mean = 34.2) and emotional distress (mean = 26.3). These results corroborate previous studies that have identified heightened levels of anxiety in individuals diagnosed with neurodevelopmental disorders, particularly those with ASD and ADHD. The research reinforces earlier assertions that anxiety is a widespread concern within neurodiverse populations, significantly affecting their daily functioning and academic success.

This finding supports previous findings that noted that neurodiverse students are at increased risk for mental health comorbidities[10,11] due to high levels of impairments associated with their conditions. The considerable range of anxiety scores (37 to 77) underscores the variability in anxiety experiences among neurodiverse students, which may be shaped by factors such as environmental stressors and the availability of support systems in educational contexts. Additionally, these findings are consistent with research indicating that neurodiverse students face increased susceptibility to mental health issues due to challenges such as social interactions, sensory sensitivities, and difficulties in emotional regulation. This study contributes to the existing literature by affirming that anxiety remains a significant issue within this demographic, highlighting the need for more focused interventions[14]. Other studies that show a high prevalence of psychological distress among students[24,25] are supported by the findings of the present study. These findings provide further support to Chapman’s assertion[5] that mental health can manifest easily in individuals with neurodiverse conditions. This indicates a link between neurodiverse conditions and mental health challenges among neurodiverse students. This assertion is echoed by other experts in the field such as Gillespie-Lynch et al[26], who highlighted that autistic students often encounter unique challenges, and Ferenc et al[6], Slokan and Ioannou[7] who found that autistic individuals are more prone to distress. In addition, the present finding supports a finding by Peraire et al[27] that individuals with ASD frequently experience psychiatric conditions. Lastly, the present finding supports a study that observed that neurodiverse conditions may be characterized by emotional distress[13]. The prevalence of emotional distress, depression, and anxiety among this population raises important concerns, as it highlights the urgent need for effective interventions and support systems.

The second aim of the study was to investigate the interconnections among emotional distress, depression, and anxiety. Notable positive correlations were identified among these mental health factors, with the most pronounced correlation occurring between depression and anxiety (Spearman’s rho = 0.492, P < 0.001). This finding is in line with existing literature, which frequently characterizes depression and anxiety as co-occurring disorders, especially within neurodiverse populations[3]. Additionally, a moderate correlation was found between emotional distress and depression (rho = 0.445, P < 0.001), supporting previous research that suggests emotional dysregulation may precede the onset of depressive symptoms[28].

Interestingly, the correlation between emotional distress and anxiety was the weakest (rho = 0.181, P = 0.010), indicating that, although these conditions are interconnected, they may be driven by distinct underlying factors. This finding addresses a gap in the current literature, as numerous studies have often regarded emotional distress, depression, and anxiety as interchangeable constructs. The results of this study underscore the importance of differentiating between these conditions when formulating interventions, as addressing emotional distress may not effectively reduce anxiety symptoms and vice versa.

Several other studies have explored this relationship, and their findings have been corroborated by the present research. One notable study that aligns with the current findings is the work of[28]. Their research highlighted the significance of emotional distress as a precursor of depressive symptoms and anxiety. Nesbitt and Giombini[29], Oh and Kim[30] provided compelling evidence of the relationship between emotional distress and both depressive symptoms and anxiety. These investigations highlighted the importance of addressing emotional distress to effectively alleviate the co-occurring symptoms. Furthermore, the present findings align with another study, conducted by Szabó[31], which proposed a novel perspective on the relationship between depressive symptoms and anxiety. Szabó's work[31] argued that depressive symptoms are not merely characterized by sadness, but rather by excessive and uncontrollable anxiety. This perspective is supported and echoed by the present findings, which further contribute to the understanding of depressive symptoms within a psychological context.

The third objective of this study examine how the characteristics of participants, including gender, educational settings, and diagnosis, influence emotional distress, depression, and anxiety. The study revealed moderate evidence of gender differences in emotional distress, as demonstrated by the Bayesian Mann-Whitney U test (BF10 = 2.448). This finding aligns with prior research indicating that females may experience greater emotional distress than males[31], potentially due to gender-specific socialization and a higher tendency to internalize stressors. However, the lack of significant gender differences in depression and anxiety challenges some existing literature that has reported elevated rates of these conditions in females relative to males[32]. These results imply that gender differences in emotional distress may be more complex within neurodiverse populations and could be influenced by factors such as age and particular diagnoses. Studies have shown that females may be more susceptible to developing anxiety and depression disorders compared to males, which may contribute to the observed difference in mean scores for emotional distress[33].

The findings further indicated that the educational setting by itself did not exhibit a statistically significant impact on emotional distress, depression, or anxiety when evaluated in isolation. This outcome diverges from several prior studies, which have posited that specific educational contexts, especially those related to special education, might exert either beneficial or harmful influences on the mental well-being of neurodiverse students, contingent upon the level of support and inclusivity present in those environments[34]. Nevertheless, the findings from the Kruskal-Wallis test revealed significant variations in anxiety levels among different educational settings (P = 0.002), underscoring the importance of the educational context in shaping anxiety. This is particularly pertinent, as earlier research has shown that neurodiverse students in mainstream educational institutions frequently face increased anxiety due to issues related to social inclusion, bullying, and academic demands[35].

However, post-hoc analyses indicated that there were no statistically significant differences in anxiety levels among specific educational settings (such as mainstream, special education, or alternative learning environments). This implies that variables beyond the general classification of educational settings may be affecting student anxiety levels. For example, the quality of personalized support, the nature of teacher-student relationships, and peer interactions within these environments may serve as more significant factors influencing mental health outcomes than the type of educational setting itself.

The relationship between educational setting and diagnosis significantly influences emotional distress, as indicated by the findings (F = 3.106, P = 0.017). This suggests that the effects of an educational environment differ according to a student's specific diagnosis. For instance, students with ASD in mainstream educational settings may encounter distinct stressors, such as sensory overload and challenges in social communication, which can lead to increased emotional distress. In contrast, students with ADHD or SLD in specialized educational settings may experience lower levels of distress due to the provision of customized support and accommodations. This research supports the finding that students with ASD are more likely to experience anxiety and depression compared to those with other neurodevelopmental disorders[36]. These results address a significant gap in the existing literature by highlighting the necessity of considering both diagnosis and educational context when evaluating the mental health of neurodiverse students. Prior research has frequently analyzed these elements separately; however, this study emphasizes the critical role of their interaction in influencing mental health outcomes. Consequently, interventions mustn't be generalized but rather customized to meet the unique needs of students, taking into account their diagnosis and educational setting.

The findings of this study yield several significant implications for the mental health support of neurodiverse students:

Customized mental health strategies: The notable prevalence of anxiety, along with depression and emotional distress, among neurodiverse students highlights the critical necessity for specialized mental health strategies. Educational institutions and mental health practitioners should create and implement programmes specifically aimed at addressing anxiety within this demographic, while also offering assistance for depression and emotional regulation.

Thorough mental health framework: The strong correlations identified between emotional distress, depression, and anxiety indicate that these conditions are interrelated. Consequently, a thorough approach to mental health care is essential. Interventions should simultaneously tackle all three aspects rather than treating them as separate issues.

Individualized educational assistance: The interaction between educational context and diagnosis of emotional distress reveals that the effects of educational environments differ based on a student's specific diagnosis. This highlights the need for individualized educational plans that consider both the student's diagnosis and the features of their learning environment.

Gender-informed strategies: The moderate evidence indicating gender differences in emotional distress suggests that mental health support strategies may require different tailoring for male and female neurodiverse students. Educators and mental health professionals should recognize potential gender-specific vulnerabilities and strengths.

Improved teacher education: Considering the intricate relationship between educational contexts, diagnoses, and mental health outcomes, there is a pressing need for improved teacher education. Educators should be trained to identify and address the diverse mental health requirements of neurodiverse students across various educational settings.

Collaborative care model: The results highlight the significance of collaboration among educational institutions, mental health practitioners, and families. A unified approach that includes all relevant parties is essential for delivering comprehensive support to neurodiverse students.

Early intervention and screening: The notable prevalence of mental health issues within this demographic highlights the necessity for prompt identification and intervention. It is imperative to implement regular mental health screenings in educational environments to identify and address concerns before they worsen.

Inclusive educational practices: Although the type of educational environment did not have a substantial effect on mental health outcomes, the research indicates that specific elements within these environments may play a critical role. This emphasizes the need for the development of inclusive educational practices that promote the mental well-being of neurodiverse students across various learning contexts.

Further research: The study identifies multiple areas that warrant additional exploration, such as the particular factors within educational settings that affect mental health outcomes and the long-term effects of various support strategies. Ongoing research in these domains is vital for establishing evidence-based practices.

Policy development: The insights gained from this study should guide policy formulation at both institutional and governmental levels. Policies must prioritize mental health support for neurodiverse students and ensure that educational institutions are adequately equipped to address their diverse needs. By addressing these implications, educational institutions, mental health professionals, and policymakers can collaborate to foster more supportive and inclusive environments for neurodiverse students, ultimately enhancing their mental health outcomes and overall well-being.

The findings and methodology of the study present several important limitations that warrant consideration:

Sample composition: Although the study involved a considerable sample size of 200 participants, the representation of various neurodevelopmental conditions was not balanced. Specifically, there were only 8 participants diagnosed with SLD, which may restrict the generalizability of the results pertaining to this particular subgroup. We did not exclude this group as we wanted to be inclusive of different neurodevelopmental conditions, but we agree with the small sample limits conclusions for SLD specifically.

Cross-sectional design: The research utilized a cross-sectional design, capturing a momentary view of participants' mental health at a single time point. This approach limits the capacity to establish causal relationships or monitor changes in mental health over time.

Self-report measures: The assessment of emotional distress, depression, and anxiety relied on self-report questionnaires. Although these measures are validated, self-reported data may be influenced by biases such as social desirability and recall inaccuracies.

Limited exploration of contextual factors: While the study considered the effects of educational environments, it may not have thoroughly examined the complexities of these settings or other contextual elements that could affect mental health outcomes, including family dynamics, socioeconomic status, or access to mental health resources.

Lack of control group: The research exclusively focused on neurodiverse students, omitting a neurotypical control group. This absence limits the ability to ascertain whether the identified mental health patterns are specific to neurodiverse individuals or indicative of broader trends within the student population.

Potential comorbidities: The study may not have adequately addressed potential comorbidities beyond the primary neurodevelopmental diagnoses, which could have an impact on mental health outcomes.

(1) Insufficient evaluation of severity: The research appears to lack an assessment of the severity of neurodevelopmental disorders, which is a crucial element in comprehending mental health outcomes;

(2) Potential symptom overlap: There exists a possibility of symptom overlap between neurodevelopmental disorders and mental health conditions, which may complicate the analysis of the findings;

(3) Inadequate investigation of protective factors: The study predominantly concentrated on risk factors and cha

These limitations indicate potential avenues for future research and underscore the necessity for caution when interpreting and generalizing the results of the study. Subsequent research could mitigate these limitations by incorporating larger and more diverse samples, utilizing longitudinal methodologies, adopting mixed methods approaches, and examining a broader spectrum of contextual and individual factors that may impact mental health in neurodiverse populations.

(4) Incomplete assessment of severity: The investigation seems to have not evaluated the severity of neurodevelopmental disorders, which is a significant aspect of understanding mental health outcomes;

(5) Possible symptom overlap: There may be an intersection of symptoms between neurodevelopmental disorders and mental health issues, which could complicate the interpretation of the findings;

And (6) Limited examination of protective factors: The research primarily emphasized risk factors and challenges, potentially overlooking protective factors or strengths associated with neurodiversity that could influence mental health outcomes.

These limitations point to potential areas for future inquiry and highlight the importance of exercising caution in interpreting and generalizing the study's conclusions. Future research could address these limitations by including larger, more diverse cohorts, employing longitudinal designs, integrating mixed methods approaches, and exploring a broader array of contextual and individual factors that may affect mental health in neurodiverse populations.

The findings of this study offer significant insights into the mental health issues encountered by neurodiverse students, particularly concerning emotional distress, depression, and anxiety. The results indicate a complex relationship among these psychological factors, emphasizing the necessity for customized interventions and support systems. Anxiety was identified as the most common mental health issue among neurodiverse students, followed by depression and emotional distress. This highlights the pressing need for interventions focused on anxiety within educational environments. Notable positive correlations were discovered between emotional distress, depression, and anxiety, with the most substantial link observed between depression and anxiety. This interconnectedness implies that addressing one mental health issue could yield beneficial effects on others. The influence of educational environments on mental health outcomes varies according to specific diagnoses, underscoring the importance of personalized strategies to support neurodiverse students. Gender differences were noted in levels of emotional distress, although no such differences were found in depression or anxiety, indicating a requirement for gender-sensitive strategies in promoting emotional well-being. Interestingly, the type of educational setting did not significantly affect mental health outcomes, suggesting that other elements, such as the quality of support and individual student characteristics, maybe more critical. These findings carry significant implications for educators, mental health practitioners, and policymakers. They highlight the necessity for inclusive mental health screening and support programmes specifically designed for neurodiverse students, as well as training for educators to identify and address mental health issues in varied educational contexts. Collaborative efforts involving educators, mental health professionals, and families are essential to foster supportive environments for neurodiverse students. Additional investigation is essential to examine the intricate relationships among neurodiversity, mental health, and educational settings. This research adds to the expanding knowledge base regarding neurodiversity and mental health, establishing a groundwork for the creation of more effective, inclusive, and supportive educational environments designed for neurodiverse learners.

We are deeply grateful for the contributions and support of many individuals involved in this study. We are especially grateful to the neurodiverse students who participated in this study and shared their stories and experiences. We acknowledge the support of the Department of Educational Psychology and Faculty of Education at the University of Johannesburg for providing general supervision and support for this research. In addition, we would like to thank the ethical committee of the Department of Counselling and Human Development Studies, University of Nigeria Nsukka for their guidance.

| 1. | Walker N. Neurodiversity: Some Basic Terms & Definitions. Neuroqueer. Jan 29, 2024. [cited 23 September 2024]. Available from: https://www.myndcrc.org/ndc-library/neurodiversity-some-basic-terms-definitions/. |

| 2. | Singer J. “Why can’t you be normal for once in your life?” From a problem with no name to the emergence of a new category of difference. In: Corker M, French S, editors. Disability Discourse. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 1999: 59–67. |

| 3. | Accardo AL, Pontes NMH, Pontes MCF. Heightened Anxiety and Depression Among Autistic Adolescents with ADHD: Findings From the National Survey of Children's Health 2016-2019. J Autism Dev Disord. 2024;54:563-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Broadhurst S. Mental Health Aspects of Autism and Asperger Syndrome. Tizard Learning Disability Rev. 2007;12:45-46. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Chapman R. Neurodiversity and the Social Ecology of Mental Functions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2021;16:1360-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ferenc K, Byrka K, Król ME. The spectrum of attitudes towards the spectrum of autism and its relationship to psychological distress in mothers of children with autism. Autism. 2023;27:54-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Slokan F, Ioannou M. ‘I'm Not Even Bothered if they Think, is that Autism?’: An Exploratory Study Assessing Autism Training Needs for Prison Officers in the Scottish Prison Service. Howard J Crime Justice. 2021;60:546-563. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Glanzman M. Temple Grandin, Kate Duffy, Developing Talents: Careers for Individuals with Asperger Syndrome and High-Functioning Autism (Second Edition). J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:266-267. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Humphrey N, Symes W. Inclusive education for pupils with autistic spectrum disorders in secondary mainstream schools: teacher attitudes, experience and knowledge. Int J Incl Educ. 2013;17:32-46. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:921-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2243] [Cited by in RCA: 1984] [Article Influence: 116.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Railey KS, Love AMA, Campbell JM. A Scoping Review of Autism Spectrum Disorder and the Criminal Justice System. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;8:118-144. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Robertson CE, Mcgillivray JA. Autism behind bars: a review of the research literature and discussion of key issues. J Forensic Psychi Ps. 2015;26:719-736. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Dobiala E, Stefańska-klar R, Rumińska A, Golaska-ciesielska P, Duras M, Janiak W. Challenges of Psychological Therapy Work With Autistic Adult. Glob Psychother. 2021;1:45-56. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | McKenney EE, Brunwasser SM, Richards JK, Day TC, Kofner B, McDonald RG, Williams ZJ, Gillespie-Lynch K, Kang E, Lerner MD, Gotham KO. Repetitive Negative Thinking As a Transdiagnostic Prospective Predictor of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Neurodiverse First-Semester College Students. Autism Adulthood. 2023;5:374-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Spence SH, Rapee RM. The development and preliminary validation of a brief scale of emotional distress in young people using combined classical test theory and item response theory approaches: The Brief Emotional Distress Scale for Youth (BEDSY). J Anxiety Disord. 2022;85:102495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Björgvinsson T, Kertz SJ, Bigda-Peyton JS, McCoy KL, Aderka IM. Psychometric properties of the CES-D-10 in a psychiatric sample. Assessment. 2013;20:429-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385-401. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Essau CA, Olaya B, Pasha G, Gilvarry C, Bray D. Depressive symptoms among children and adolescents in Iran: a confirmatory factor analytic study of the centre for epidemiological studies depression scale for children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2013;44:123-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sugawara N, Yasui-Furukori N, Sasaki G, Umeda T, Takahashi I, Danjo K, Matsuzaka M, Kaneko S, Nakaji S. Assessment of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale factor structure among middle-aged workers in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65:109-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11:139-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 514] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R, Vagg P, Jacobs G. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983. |

| 22. | Spielberger C. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: Bibliography. 2nd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1989. |

| 23. | Thomas CL, Cassady JC. Validation of the State Version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory in a University Sample. SAGE Open. 2021;11:215824402110319. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Fawzy M, Hamed SA. Prevalence of psychological stress, depression and anxiety among medical students in Egypt. Psychiatry Res. 2017;255:186-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gabal HA, Wahdan MM, Gamal Eldin DA. Prevalence of anxiety, depression and stress among medical students, and associated factors. Egypt J Occup Med. 2022;46:55-74. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Gillespie-Lynch K, Bublitz D, Donachie A, Wong V, Brooks PJ, D'Onofrio J. "For a Long Time Our Voices have been Hushed": Using Student Perspectives to Develop Supports for Neurodiverse College Students. Front Psychol. 2017;8:544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Peraire M, Cantos P, Sampedro-Vidal M, Bonet-Mora L, Arnau-Peiró F. Characterization of autism spectrum disorder inside prison. Rev Esp Sanid Penit. 2023;25:30-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Feng X, Keenan K, Hipwell AE, Henneberger AK, Rischall MS, Butch J, Coyne C, Boeldt D, Hinze AK, Babinski DE. Longitudinal associations between emotion regulation and depression in preadolescent girls: moderation by the caregiving environment. Dev Psychol. 2009;45:798-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nesbitt S, Giombini L. Psychological distress and emotional experience in eating disorders. In: Nesbitt S, Giombini L. Emotion Regulation for Young People with Eating Disorders. London: Informa UK Limited, 2021. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Oh J, Kim S. The relationship between psychological distress, depressive symptoms, emotional eating behaviors and the health-related quality of life of middle-aged korean females: a serial mediation model. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Szabó M. The emotional experience associated with worrying: anxiety, depression, or stress? Anxiety Stress Coping. 2011;24:91-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kalin NH. The Critical Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:365-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 62.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Maron E, Nutt D. Biological markers of generalized anxiety disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017;19:147-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Christensen H, Jorm AF, Mackinnon AJ, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Henderson AS, Rodgers B. Age differences in depression and anxiety symptoms: a structural equation modelling analysis of data from a general population sample. Psychol Med. 1999;29:325-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zenebe Y, Akele B, W/Selassie M, Necho M. Prevalence and determinants of depression among old age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2021;20:55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 65.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bolourian Y, Zeedyk SM, Blacher J. Autism and the University Experience: Narratives from Students with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48:3330-3343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |