INTRODUCTION

Being a major global healthcare burden, depression has been a leading source of years lived with disability over the last 30 years. Persistent depression (defined as episodes lasting > 12 months) may be as common as 61% among patients receiving depression treatment at primary and secondary healthcare facilities, with recurrence rates ranging from 71% to 85%[1]. The depression’s persistent and ubiquitous nature as well as its propensity to cause disability, morbidity, and mortality indicate the pressing need to develop innovative and effective interventions.

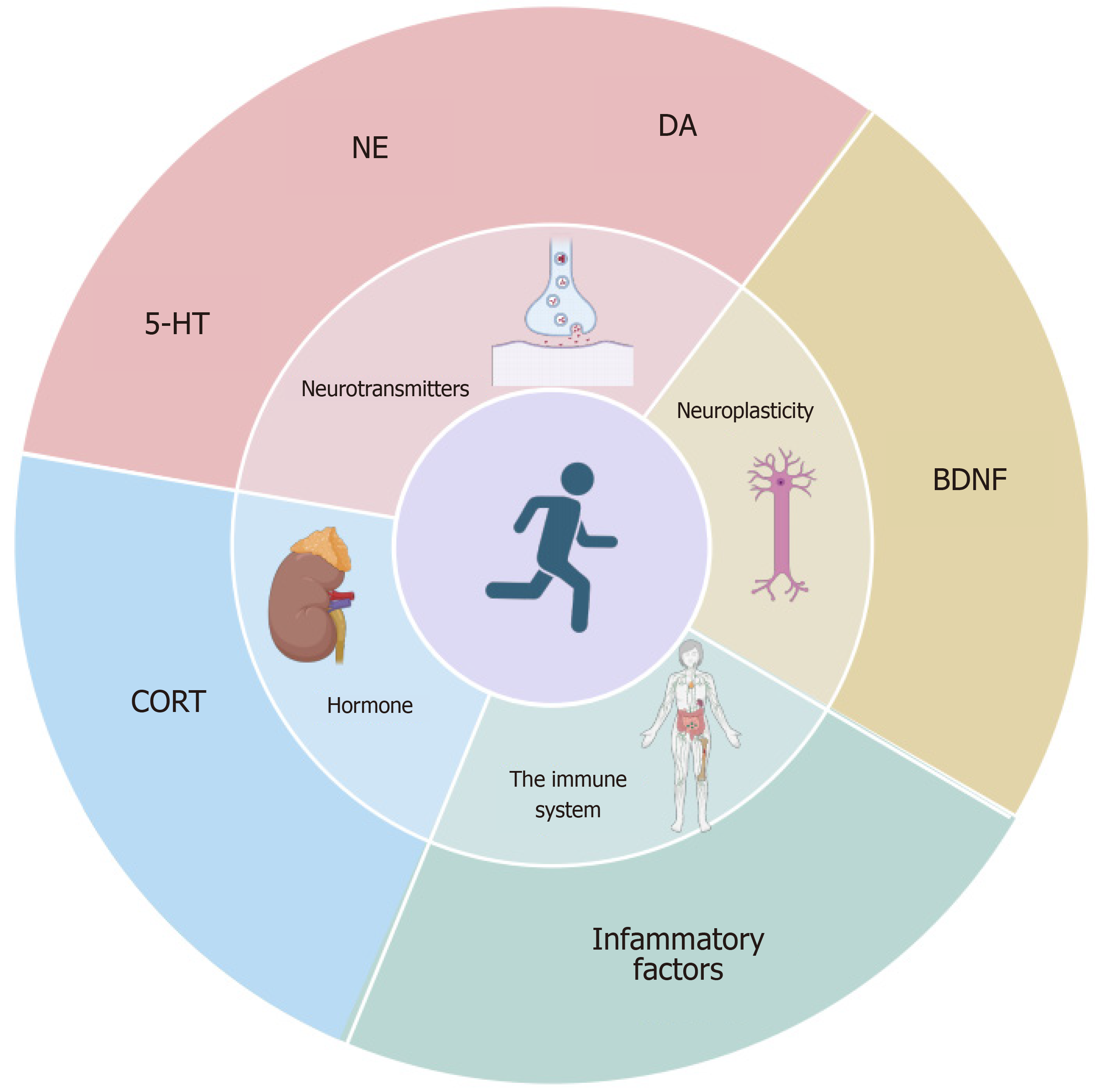

Currently, first-line antidepressant medications are ineffective in treating one-third to one-half of depression patients. These medications have several side effects, like headaches, gastrointestinal symptoms, anxiety, and sleep disturbances[2]. Antidepressants’ side effects, poor therapeutic efficacy, and slow onset of action highlight the need for alternative and adjunctive treatment options. Additionally, exercise therapy has been a major non-pharmacological intervention in recent years for depression treatment, demonstrating high safety and superior antidepressant effects (Figure 1). The use of wearable devices for regular exercise significantly reduces depression risk. Following the recommendations suggesting 2.5 hours of brisk walking perweek might prevent 11.5% of depression cases[3]. Moreover, replacing prolonged sedentary behavior with 15 minutes or 1 hour of daily vigorous or moderate activity can reduce the risk of depression by 26%[4]. Yoga, strength training, and walking/jogging are effective forms of exercise. These choices can be important components of depression treatment, with psychotherapy and medication. Practitioners should recommend exercise, considering an individual’s tolerability and preferences. Group exercises or organized programs can enhance support and outcomes, offering viable alternatives for patients unwilling to psychotherapy[5]. This editorial aims to review recent developments in the antidepressant mechanisms of exercise and to suggest the appropriate exercise forms to provide efficient supplemental therapies for managing depression.

Figure 1 Exercise improves depression by modulating neurotransmitters, neuroplasticity, the immune system, and hormonal pathways.

DA: Dopamine; BDNF: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CORT: Cortisol; 5-HT: 5-hydroxy tryptamine; NE: Norepinephrine.

ANTIDEPRESSANT EFFECTS OF EXERCISE

Sedentary behaviour increases the risk of depression

Low physical activity and high sedentary behavior can significantly influence the onset of depression. Studies on sedentary behavior and adolescents’ depressive symptoms suggest that every additional hour of sedentary behavior per day can cause an 8%-11% increase in depression scores by the age of 18. When compared to those with lower levels, participants who maintained high or moderate sedentary behavior levels between the ages of 12 years and 16 years exhibited significantly higher depression scores by the age of 18[6]. Additional research on older adults has revealed a close association between sedentary behavior (like watching TV, using computers, and sitting in cars) and light-intensity physical activity (like housework, gardening, and leisurely walks) with depression in the elderly[7].

Exercise is an effective treatment for depression

In order to minimize residual confounding and reverse causation issues in observational studies, a study used Mendelian randomization methods to assess the potential causal relationship between physical activity and depression risk. The results suggested that replacing sedentary behavior with 15 minutes of vigorous activity or 1 hour of moderate activity daily can reduce depression by 26%. This result strongly supports the hypothesis that increased physical activity can effectively prevent depression[8]. Moreover, walking/jogging, yoga, and strength training are the most effective forms of exercise for treating depression, particularly when engaging in vigorous exercises. However, different demographic groups prefer specific exercises, having diverse effects on different populations. While strength training is more beneficial for women, walking or jogging is equally effective for both men and women. Men benefit more from yoga and qigong, while older adults and younger individuals prefer tai chi and strength training, respectively. Compared to other treatments, yoga, and strength training have better tolerability. Moreover, dancing has the highest therapeutic effect size. However, more studies are required to validate its inclusion as a recommended exercise form due to fewer studies and the small sample size with a single category of participants[5].

Although exercise is effective in preventing depression, the required dosage is ambiguous. Moreover, the diversity of assessment methodologies employed in such studies complicates data integration and establishes a precise dose-response relationship between physical activity and depression risk.

To overcome this challenge, a systematic review and meta-analysis converted distinct physical activities, intensities, and frequencies into marginal metabolic equivalent tasks (mMET) for analysis. The mMET represents the ratio of energy expenditure during an activity to that at rest; higher mMET values display greater activity intensity. Moreover, 8.8 mMET hours of activity per week is equivalent to approximately 2.5 hours of moderate-intensity exercise, like brisk walking[9]. Additional analysis indicated that a physical activity level of 4.4 mMET hours per week reduced the risk of depression by 18% (95%CI: 13%-23%). Although increasing the amount to 8.8 mMET hours per week corresponded to a 25% lower risk (95%CI: 18%-32%), the advantages of engaging in activity beyond this threshold were not statistically significant[9].

Less physical activity reduces the depression risk

While extensive vigorous activity may be beneficial for physical outcomes, maintaining a regular and high-intensity exercise schedule is challenging for depressed individuals with low energy and motivation. Fortunately, the optimal intensity, duration, and type of physical activity might depend on the specific targeted outcomes. Research suggests that marginal benefits are observed at higher activity levels[10]. Hence, lighter activity levels may be sufficient for depression, considering the challenges depressed individuals face in sustaining a high-intensity exercise schedule.

THE MECHANISM OF EXERCISE AGAINST DEPRESSION

Exercise and neurotransmitters

According to depression's clinical pre-chronic stress model, depression is associated with reduced 5-hydroxy tryptamine (5-HT) levels in the hippocampus (HPC), prefrontal cortex (PFC), and striatum, as well as decreased norepinephrine (NE) levels in PFC and HPC[11]. Reduced dopamine (DA) metabolism and activity in individuals with depression correlate with a decrease in reward anticipation within the striatum, culminating in anhedonia[12]. Physical activity enhances the 5-HT and NE concentrations in the brain, thereby facilitating synaptic transmission, and reducing depressive-like behaviors. Moreover, aerobic exercise can acutely affect serotonergic and noradrenergic activities in depression patients[13]. Exercise can also activate the downstream phospholipase C signaling pathway to promote increased DA release from dopaminergic neuron terminals[14].

Exercise and neuroplasticity

Chronic physical activity induces structural and functional plasticity, leading to the benefits of exercise. Both low-intensity and high-intensity aerobic and resistance training positively influence cognitive function, brain activation, and structure as well as neuroplasticity neurochemical markers and their associations in healthy young and older individuals, as well as neurological disorder patients[15].

By influencing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), vascular endothelial growth factor, kynurenine pathway metabolism, and neuroinflammation, exercise promotes neural plasticity and improves cognitive functions in depressed patients[16]. BDNF is a pivotal neuronal plasticity factor that facilitates axon extension and the formation of new branches within the brain's motor units. It also enhances neuronal connectivity and synaptic plasticity, thereby improving memory and cognitive function in depression patients[17]. Regular aerobic exercises result in elevated BDNF levels, pivotal for the neurogenesis of the hippocampal dentate gyrus[16]. Recent research suggests that regular weekly exercises can alleviate depressive symptoms and mitigate the detrimental effects of the BDNF Val66Met allele on cognitive functions. This indicated a potential link between exercise efficacy and BDNF gene polymorphism[18]. Exercises also enhance the brain’s BDNF expression by activating proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α)[19]. Through BDNF expression induction and the promotion of brain neuroplasticity processes, exercise contributes to the improvement of cognitive function and antidepressant effects. Additionally, exercise maintains hippocampal and white matter volume integrity, promotes hippocampal neuronal regeneration, and activates prefrontal cortical functions in depressed patients. Therefore, these effects collectively can decelerate cognitive deterioration and effectively preserve the brain's plasticity[20].

Exercise and the immune system

Chronic stress from environmental and psychological factors disrupts homeostasis and activates the sympathetic nervous system as well as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and modifies the levels of neurotransmitters, neurochemicals, and hormones[11]. Major depressive disorder can induce systemic immune activation, evidenced by differences in inflammatory markers, immune cell counts, and antibody titers. Increased pro-inflammatory cytokine and stress hormone levels cause behavioral changes in depression[21]. Moreover, exercise interventions increase PGC-1α expression and reduce the brain's inflammatory cytokine expressions[22,23], thereby mitigating neuroinflammation and enhancing cognitive functions. Since acute stressors boost immune function and chronic stressors suppress it, an imbalance is created between pro- and anti-inflammatory effects. Pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha stimulate the HPA axis and enhance adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and glucocorticoid cortisol (CORT) levels[11]. This then reduces their production and creates an immune-HPA axis negative feedback cycle[24]. Exercise also increases the kynurenine aminotransferase enzymes in the muscle, which is dependent on PGC-1α. This process converts neurotoxic kynurenine into neuroprotective kynurenine, thereby modulating the immune responses and reducing depression symptoms[25].

Regulation of hormone levels by exercise

The chronic stress coexisting with depression significantly enhances CORT levels. This damages hippocampal neurons and elevates corticosterone and ACTH levels on the HPA axis. This process is responsible for the physiological and biochemical mechanisms of stress-induced depression[26]. Elevated CORT levels cause chronic stress-induced cognitive impairment, inhibition of brain structural and functional plasticity, and depression. While both physical exercise and chronic stress can elevate CORT levels, exercise-induced basal CORT enhancement might be advantageous rather than deleterious[27]. This apparent paradox can be explained by several biological mechanisms. Firstly, exercise increases CORT levels momentarily and modulates the reactivity of the HPA axis, resulting in an enhanced adaptive response to stress[28]. Secondly, exercise enhances DA levels in the medial PFC and facilitates positive coping behaviors[27]. Additionally, exercise can maintain or upregulate mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor expressions, thereby reducing stress-related depressive behaviors[29]. Although both chronic stress and exercise can enhance CORT levels, exercise exerts protective and restorative effects through the aforementioned mechanisms, in contrast to the detrimental effects of chronic stress. Thus, these complex interactions emphasize the benefits of exercise as a non-pharmacological intervention in treating depression.

CONCLUSION

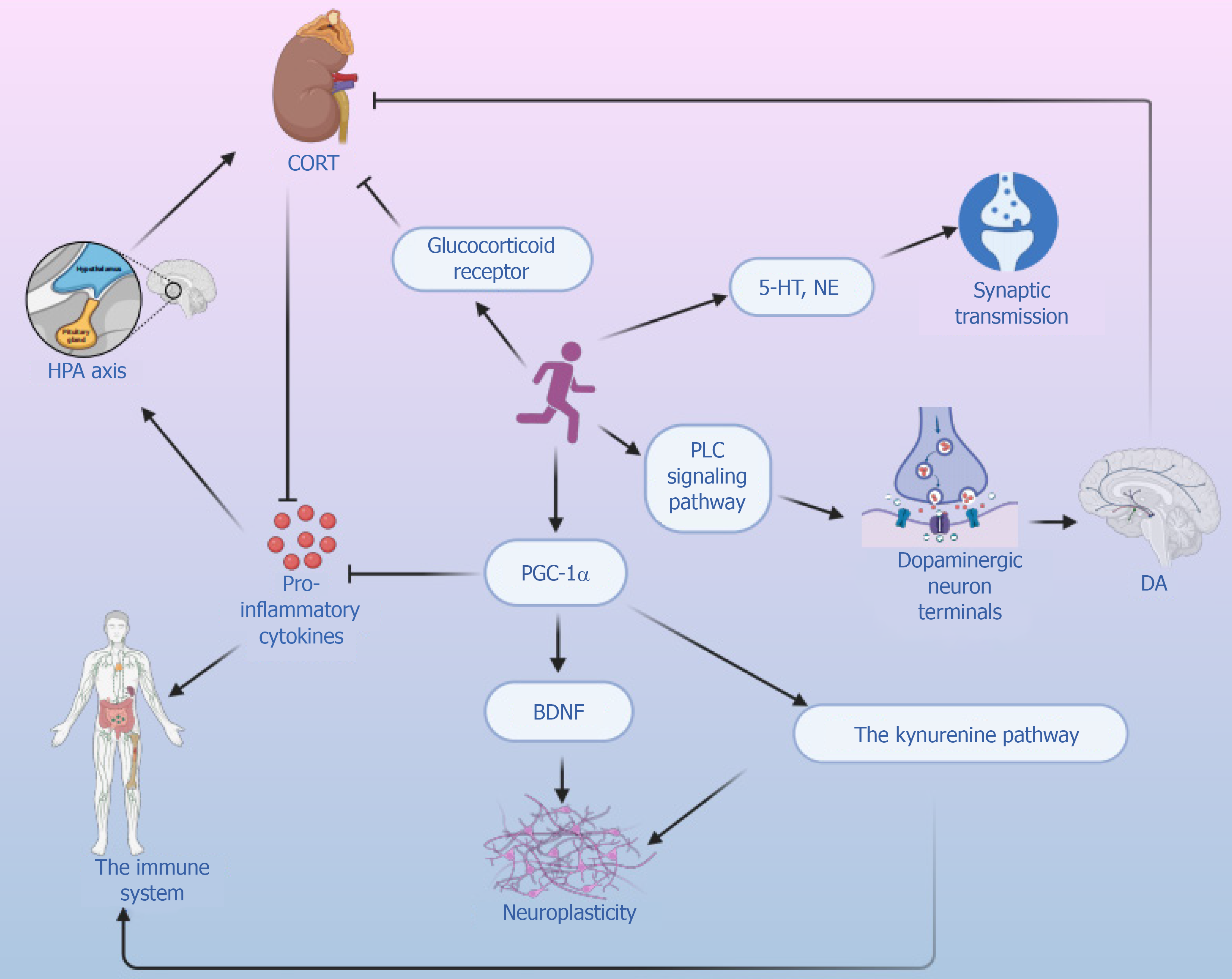

Exercise is an effective alternative treatment option because of antidepressants’ limited acute and long-term efficacy as well as the frequent treatment resistance and side effects in patients. Acute exercise transiently modulates circulating 5-HT, NE, and BDNF levels as well as various immune-inflammatory mechanisms in depression’s clinical cohorts. Additionally, exercise activates the HPA axis, increases CORT levels, prevents/reverses depression, improves cognition, and promotes plasticity of the brain structure and function (Figure 2). Because of depression’s complex physiology and intricate exercise-induced responses, research on the impact of exercise on depression is limited. Nevertheless, exercise therapy should be studied further as an accessible, low-cost complementary intervention for reducing depression and improving overall health. Thus, we offer the following exercise recommendations for depression clinically. Moreover, 2.5 hours of brisk walking per week is the minimum physical activity level for combating depression. Out of all the exercise forms, yoga, strength training, and walking/jogging have demonstrated the strongest antidepressant effects. Additionally, less low-intensity activity can exert a positive impact on depression. However, the physical activity guidelines should be tailored to individual patient’s specific preferences and circumstances. To develop more scientifically sound and personalized exercise prescriptions for patients, the incorporation of modern medical devices is a viable option. For instance, the use of wearable devices and artificial intelligence can facilitate real-time monitoring of patients' exercise data and provide immediate feedback and personalized adjustment recommendations, thereby ensuring the effectiveness and safety of the prescription[30].

Figure 2 Molecular mechanisms underlying exercise's antidepressant effects.

DA: Dopamine; BDNF: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CORT: Cortisol; 5-HT: 5-hydroxy tryptamine; NE: Norepinephrine; HPA: Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; PLC: phospholipase C; PGC-1α: Proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1-alpha.

In summary, exercise is an effective alternative therapy for depression and can be included in clinical treatment plans. However, there are several challenges in implementing it. Because of the diversity in assessment methods and inconsistencies in exercise prescription parameters, precise analysis of the dose-response relationship between physical activity and health outcomes is difficult. Physical activity guidelines have difficulty in setting measurable and attainable exercise targets due to the lack of high-quality evidence regarding dose responses. Although exercise exerts antidepressant effects by regulating 5-HT, NE, DA, and BDNF levels as well as various depression-related immune-inflammatory mechanisms, the potential for exercise to produce long-lasting regulatory effects is unknown. These limitations underscore the importance of future research in this area. Additional studies are required to elucidate the molecular biology mechanisms of exercise in combating depression and adopt more standardized exercise parameters to assess the expected dose-response relationship between exercise and depression more comprehensively. These findings can propagate the complete clinical therapeutic efficacy of various exercise forms. Furthermore, the theories regarding exercise as an antidepressant also should be assessed in more prospective epidemiological studies. Additionally, robust experimental designs are necessary to evaluate the universality of their antidepressant effects across diverse demographic areas for activities like dancing, walking, jogging, yoga, and strength training. Moreover, it is essential to create novel and more effective exercise formats. Thus, future studies can investigate innovative approaches that integrate cutting-edge technologies, like artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and telemedicine to boost receptivity and adherence to various exercise-based interventions.